Abstract

For human listeners, the primary cues for localization in the vertical plane are provided by the direction-dependent filtering of the pinnae, head, and upper body. Vertical-plane localization generally is accurate for broadband sounds, but when such sounds are presented at near-threshold levels or at high levels with short durations (<20 ms), the apparent location is biased toward the horizontal plane (i.e., elevation gain <1). We tested the hypothesis that these effects result in part from distorted peripheral representations of sound spectra. Human listeners indicated the apparent position of 100-ms, 50–60dB SPL, wideband noise-burst targets by orienting their heads. The targets were synthesized in virtual auditory space and presented over headphones. Faithfully synthesized targets were interleaved with targets for which the directional transfer function spectral notches were filled in, peaks were levelled off, or the spectral contrast of the entire profile was reduced or expanded. As notches were filled in progressively or peaks levelled progressively, elevation gain decreased in a graded manner similar to that observed as sensation level is reduced below 30dB or, for brief sounds, increased above 45dB. As spectral contrast was reduced, gain dropped only at the most extreme reduction (25% of normal). Spectral contrast expansion had little effect. The results are consistent with the hypothesis that loss of representation of spectral features contributes to reduced elevation gain at low and high sound levels. The results also suggest that perceived location depends on a correlation-like spectral matching process that is sensitive to the relative, rather than absolute, across-frequency shape of the spectral profile.

Keywords: sound localization, spectral cues, virtual auditory space, head-related transfer functions, negative level effect

1. Introduction

For human listeners, the primary cues for sound localization in the vertical dimension are provided by the direction-dependent acoustical filtering of the pinnae, head, and upper body. The resulting spectral cues complement the interaural time- and level-difference cues that are the primary determinants of apparent location in the horizontal dimension. Vertical-plane localization is generally accurate for broadband sounds, but under certain stimulus conditions, a characteristic pattern of localization errors is observed that includes bias (or compression) of the apparent location toward the horizontal plane, increased rates of front/rear reversals, and increased response scatter. Such patterns of errors occur as stimulus level is reduced at low levels and as level is increased above some optimum for sounds with durations below a few tens of milliseconds.

The decline in vertical-plane localization performance at sensation levels below ~30 dB is known as the Level Effect since localization accuracy is positively correlated with stimulus level within this range (Vliegen and Van Opstal, 2004; Sabin et al., 2005). We have hypothesized that the Level Effect is due in part to high-frequency portions of the stimulus spectrum falling below the minimum audible pressure when stimulus levels are low (Sabin et al., 2005). The primary spectral cues for vertical-plane localization lie above 4–6 kHz (Hebrank and Wright, 1974), and the minimum stimulus intensity required for detection rises sharply at high frequencies.

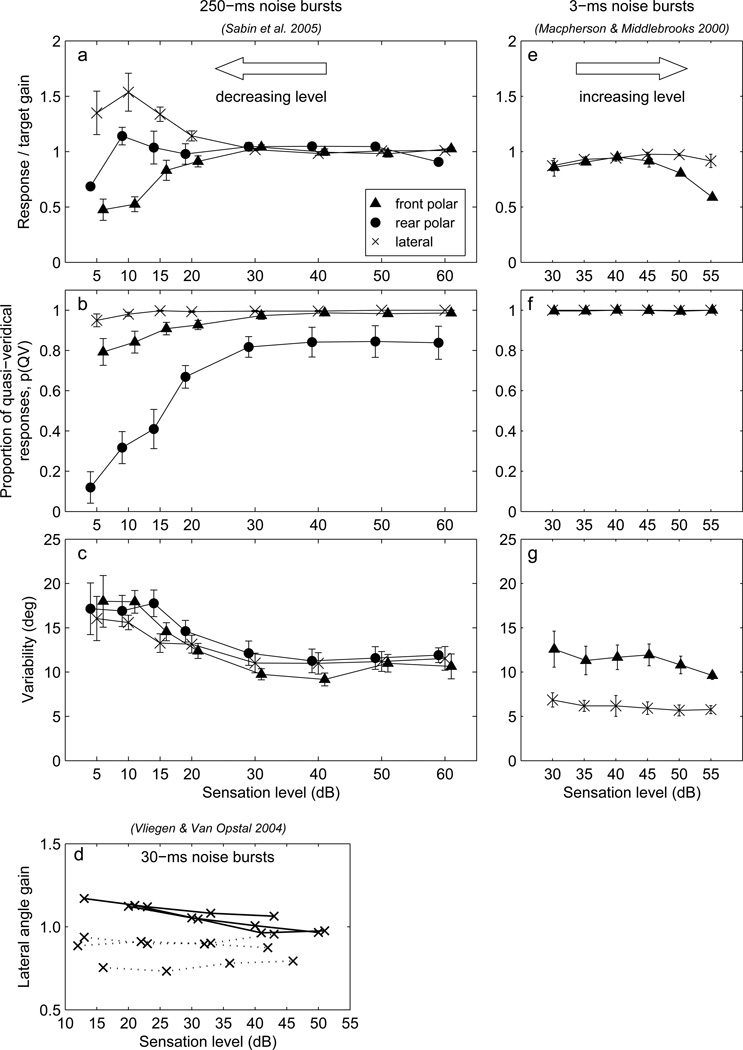

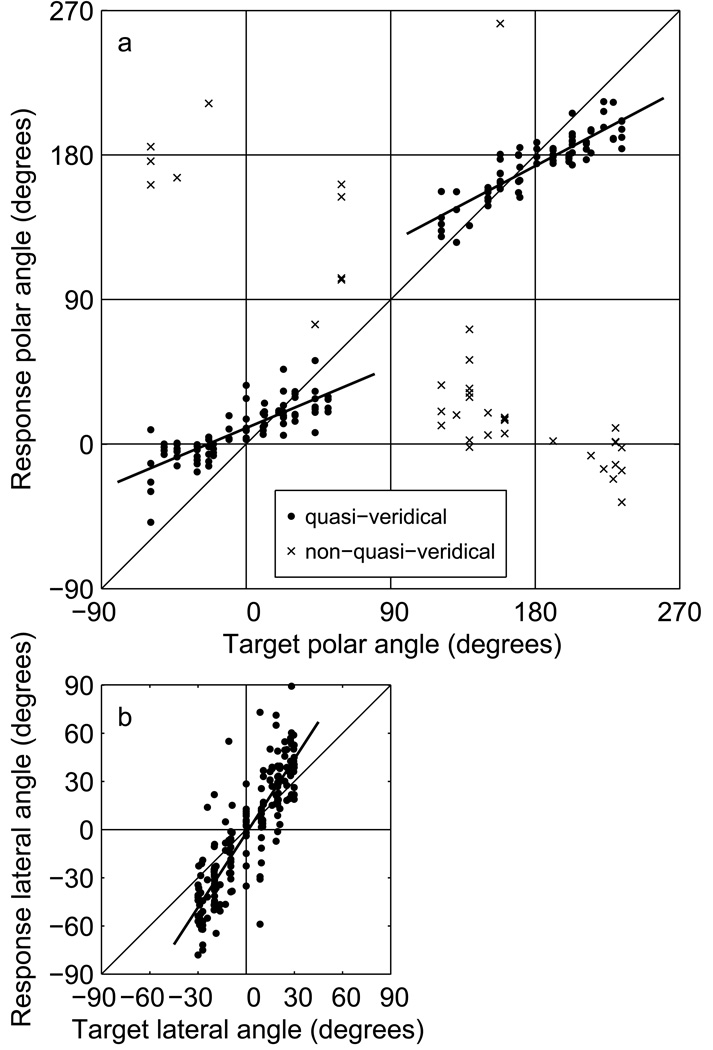

Figures 1a – c illustrate the Level Effect for 250-ms, wideband noise bursts presented at a range of levels from 5–60 dB relative to the absolute detection threshold for a source straight in front of the listener (subset of data from Sabin et al., 2005). In those plots, listeners’ vertical-plane performance is quantified by: the polar-angle gain, defined as the slope of the line fit between the vertical components of response and target locations (Fig. 1a); the proportion of quasi-veridical responses, essentially the proportion of non-front/rear reversed responses (Fig. 1b); and the variability of quasi-veridical responses (Fig. 1c). The computation of those values is described in detail in Sec. 3.1. As stimulus level decreases, polar-angle gain and quasi-veridical response rate decrease and polar- and lateral-angle variability increases. At the lowest sensation levels, lateral angle gain for near-midline targets increases for some listeners (Fig. 1a), and this is also evident in the data of Vliegen and Van Opstal (2004, Fig. 3) for 30-ms noise bursts that are replotted in Fig. 1d.

Figure 1.

Level- and negative-level effects in vertical-plane localization. a–c: Data (selected to match the locations used in the present study) from Sabin et al. (2005) showing the level effect, the reduction in polar-angle gain observed as sensation level is reduced below 30 dB. a: Response/target lateral and polar angle gains, b: proportion of quasi-veridical responses, c: response variability. See text for definitions of these measures. d: Lateral angle gain as a function of sensation level for 30-ms noise bursts. Replotted data from Vliegen and Van Opstal (2004), Fig. 3, showing results for six listeners. Three listeners had gains that increased as stimulus level decreased (solid lines), and three had gains that did not vary systematically with level (dotted lines). The data for the latter have been shifted downwards by 0.1 for clarity. e–g: Data from Macpherson and Middlebrooks (2000) showing the negative-level effect, the reduction in polar-angle gain for brief (3-ms) wide band noise bursts as stimulus level is increased above 45 dB sensation level. 250-ms noise bursts were not similarly affected over the same range of sensation levels (panels a–c).

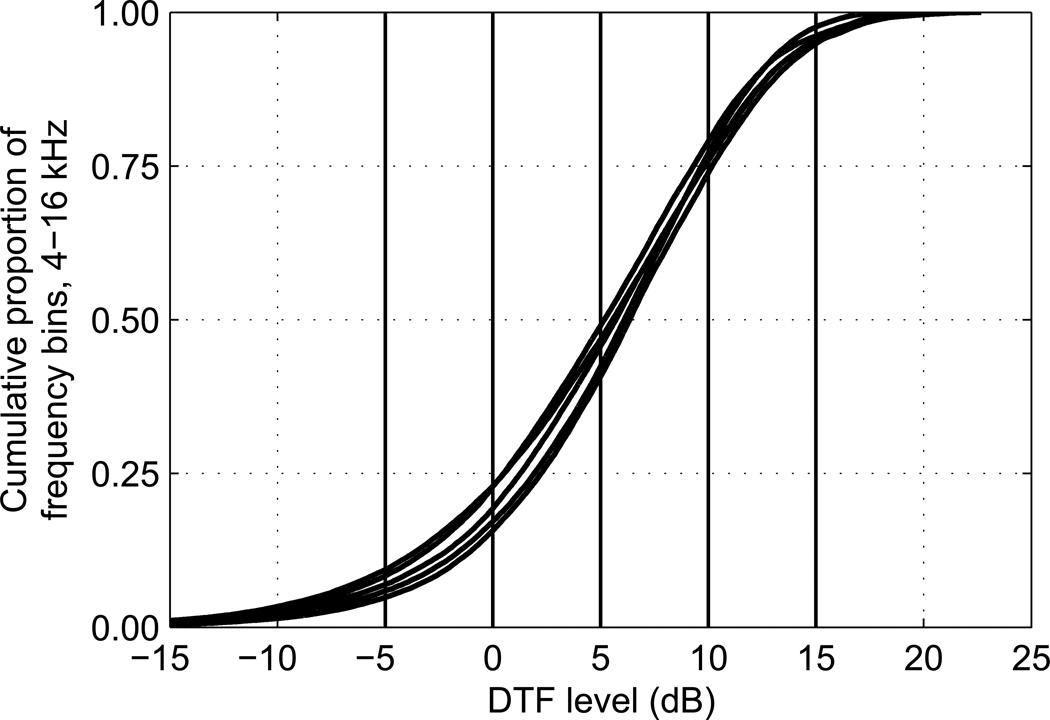

Figure 3.

Distribution of DTF magnitudes. The cumulative distributions of DTF magnitudes across frequency and across right-hemisphere locations are shown for the right ears of the five listeners who participated in Experiment I. Notch-filling and peak-levelling floor and ceiling values are indicated by the heavy vertical lines.

The compression of apparent position in the vertical dimension also increases as the intensity of short-duration sounds (shorter than a few tens of milliseconds) is increased for sensation levels above ~45dB (Hartmann and Rakerd, 1993; Macpherson and Middlebrooks, 2000; Vliegen and Van Opstal, 2004; Gai et al., 2013). This is referred to as the Negative Level Effect since localization accuracy is negatively correlated with stimulus intensity under such circumstances. We have hypothesized that the Negative Level Effect is due in part to a degraded representation of spectral cues in the auditory periphery caused by saturation or compression in the cochlear response to brief, high-intensity stimuli and that the auditory system, perhaps by means of efferent control, is able to partially compensate for this over the duration of longer stimuli (Macpherson and Middlebrooks, 2000; Macpherson and Wagner, 2008). The increased opportunity for temporal integration at longer durations is another possible contributor to this compensation.

Figures 1e – g illustrate the Negative Level Effect for 3-ms wideband noise bursts (data from Macpherson and Middlebrooks, 2000) presented in the front hemisphere and within 30 degrees of the horizontal plane. Reduction in polar-angle gain is the most obvious correlate of increasing stimulus level in this data set (Fig. 1e). Responses to the 250-ms stimuli were not subject to the Negative Level Effect, as evidenced by the constant polar-angle gain observed at higher levels in Fig. 1a. Gai et al. (2013) have recently shown that awake behaving cats exhibit very similar Level and Negative Level Effects, and with the use of an auditory nerve model those authors have also demonstrated that the fidelity of peripheral spectral cue coding is significantly reduced at low and high stimulus intensities.

For short-duration stimuli, the combination of the Level and Negative Level Effects results in optimal localization performance at intermediate stimulus levels. This is the converse of the “severe departure” from Weber’s Law described by Carlyon and Moore (1984) for intensity discrimination of brief, high-frequency tone bursts in notched noise. For such stimuli, intensity discrimination performance is worst (difference limens are highest) at an intermediate level (55 dB SPL), but recovers at higher levels (85 dB SPL). Those authors hypothesized that the recovery at high levels might be due to a combination of reduced basilar membrane compression at high levels and the engagement of a secondary population of high-threshold auditory nerve fibers.

It should also be noted that another factor in addition to stimulus intensity and duration can cause systematic biases in vertical-plane localization has been identified. That factor is the temporal fine structure of the stimulus waveform. Localization targets composed of wideband complexes of harmonics in cosine phase, sine phase, and positive or negative Schroeder phase (chirps) cause significant compression of perceived elevation even for long durations and moderate intensities, and are also subject to the Negative Level effect, whereas long-duration random-phase harmonic complexes and noise bursts are not subject to these effects (Brungart and Simpson, 2008; Hartmann et al., 2010). Hofman and Van Opstal (1998) also observed compression of elevation for targets consisting of 500-ms trains of frequency sweeps, all with long-term spectra flat up to 16 kHz, when the sweep period exceeded 5 ms. That is, it appeared necessary that the stimulus provide wideband energy within a 5-ms integration window for successful spectral cue processing.

In the present study, we explored the hypothesis that distorted peripheral representation of spectral cues contributes to the Level Effect and to the Negative Level Effect. We did this by modifying the spectral information in stimuli which were intense enough to avoid the Level Effect, long enough to avoid the Negative Level effect, and composed of random-phase noise in order to avoid waveform fine-structure effects. Stimuli were synthesized in virtual auditory space (e.g. Wightman and Kistler, 1989) using each listener’s own normal or manipulated directional transfer functions (DTFs). The DTF manipulations we employed, based on single notional auditory-nerve rate-level functions, are undoubtedly simplistic models of whatever distortions of stimulus spectrum representation occur at low and high levels. DTF spectral profiles are more likely encoded at different stimulus intensities by multiple populations of auditory nerve fibers with a diversity of thresholds and dynamic ranges (Reiss et al., 2011). Our manipulations also do not take into account the normal compressive action of the outer hair cells at intermediate intensity levels and its absence at very low and high levels. Nevertheless, our spectral manipulations (which changed the shapes and/or sizes, but not frequency loci, of spectral peaks and notches) are of interest in their own right because they provide data with which more general theories and models of spectral cue processing can be tested.

2. Methods

The procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan Medical School. All stimulus generation, stimulus presentation, and data collection and analysis tasks were controlled by custom software written in Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc.) running on an Intel-based personal computer.

2.1. Subjects

Five paid listeners (4 female and 1 male) aged 19–25 years were recruited from the University of Michigan community. All listeners had normal hearing (audiometric thresholds ≤10dB HL at octave frequencies from 0.25–8 kHz) as determined by standard clinical audiometry. None had previous experience in sound localization or other psychoacoustic experiments. Before data collection began, all were given instruction and several hours of practice in free-field and virtual auditory space localization tasks using flat-spectrum, broadband noise targets. All five listeners participated in Experiment I, which included Notch-Filling and Peak-Levelling conditions, and four of the five participated in Experiment II, which included Contrast Compression and Expansion conditions.

2.2. Directional transfer function measurement

In order to permit the synthesis of individualized virtual auditory space stimuli, we measured each listener’s directional transfer functions (DTFs) using the procedure described by Middlebrooks (1999). Briefly, 512-point, 50-kHz Golay code pairs (Zhou et al., 1992) were presented from a loudspeaker (Infinity 32.3 CF) positioned 1.2m from the listener’s head. The loudspeaker was mounted on a movable hoop covered with sound-absorbing foam, and was located in a sound-attenuating anechoic chamber (2.6 × 3.7 × 3.2 m of usable space), the walls and ceiling of which were lined with glass-fiber wedges and the floor with foam wedges. Measurements were made at 400 locations approximately evenly distributed in space (~10-degree separation) around the listener’s head. The responses to the Golay-code excitation signals were recorded simultaneously by two miniature electret microphones (Knowles, model 1934) inserted approximately 5 mm into the listeners’ ear canals. This was deep enough to capture all spatial information independent of any ear canal resonances (Middlebrooks et al., 1989; Hammershøi and Møller, 1996).

Head-related transfer functions (HRTFs) were computed by cross-correlation of excitation and response, Fourier transformation, and the removal of the measured loudspeaker transfer function. The transfer function used for that correction was obtained similarly, in the absence of the listener, by recording the loudspeaker’s response to the Golay code excitation with a 1/2-inch reference microphone (Larson Davis, model 2540) oriented coaxially with the loudspeaker and positioned at the location of the listener’s head. DTFs for each ear were computed from the set of HRTFs by removing the root-mean-square average magnitude spectrum (i.e., the non-directional component) from the set of HRTFs for that ear. The non-directional component also contained the transfer functions of the microphones and any fixed-geometry reflections from the foam-covered hoop that supported the loudspeaker, which were thus removed by this procedure.

2.3. Directional transfer function manipulation

In the present study, we attempted to model in a simple way the distorted representations of DTF profiles that might occur at low and high levels. This was done by filling in DTF spectral notches or levelling off DTF spectral peaks (Experiment I), or by reducing DTF spectral contrast (Experiment II). The resulting virtual auditory space stimuli were then presented at levels well above threshold (50–60 dB SPL).

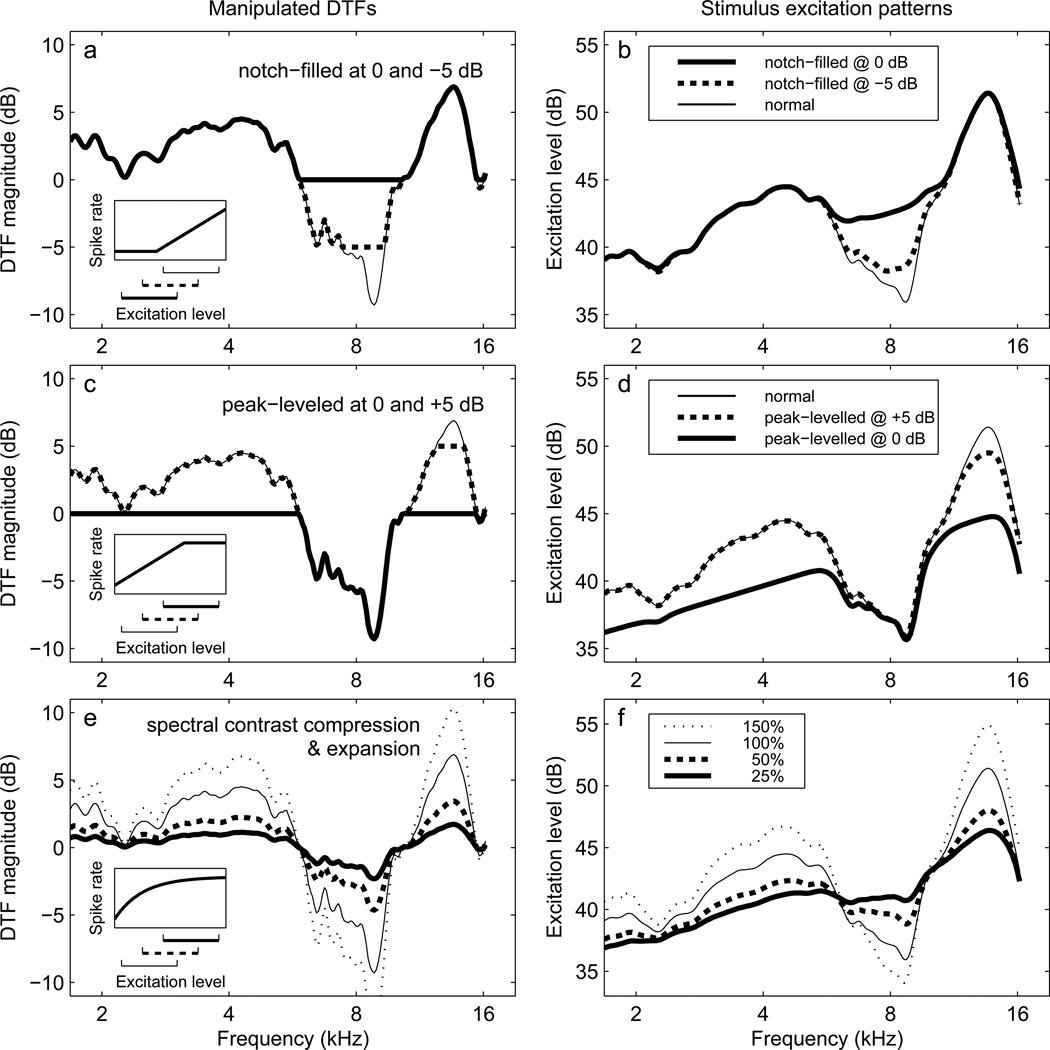

Notch filling was intended to model the Level Effect, which we hypothesized derives from a lack of representation of the spectral profile in frequency regions falling below a psychophysical (detection) or physiological (stimulation) threshold. It was accomplished by selecting a floor DTF magnitude, and then setting any portions of the DTF falling below this value to the floor value itself. This process is illustrated for floors of −5 and 0 dB in Fig. 2a. Notch-filling floor values were set at −5, 0, +5, +10, and +15dB, and a complete set of distorted DTFs was derived for each value. As the floor value was increased (intended to model reduction in stimulus level and the lowering of more and more of the stimulus spectrum below threshold), more notch-related spectral information was removed from the DTFs. The inset plot in Fig. 2a shows a hypothetical near-threshold neural rate-level function that could result in level-dependent representation of the original DTF spectrum; the three horizontal brackets below the inset illustrate how different across-frequency ranges of excitation level would interact with the rate-level function to produce distortions similar to those of the plotted DTFs.

Figure 2.

Examples of DTF manipulations and resulting excitation patterns. The right-ear DTF of listener S160 for the location at 0-degrees lateral angle and 0-degrees polar angle (straight ahead) is used in each example. Left-column panels (a, c, e) show normal and manipulated DTFs. Right-column panels (b, d, f) show corresponding excitation patterns assuming a 55-dB SPL, 0.5–16-kHz flat-spectrum input signal. Inset plots show (where meaningful) the physiological motivation for the DTF manipulations in the form of hypothetical neural rate-level functions that could produce level-dependent DTF distortions. Horizontal brackets below the insets represent the range of excitation level produced by three different stimulus intensities. a) Notch filling: original DTF (—) and notch-filled versions at −5 (- -) and 0-dB (−) floor levels. c) Peak levelling: original DTF (—) and peak-levelled versions at 0- (−) and +5-dB (--) ceiling levels e) Spectral contrast reduction and expansion: original DTF (—), contrast reduced to 50% (--) or 25% (−) of the original, or expanded to 150% of the original (…). Contrast expansion is not represented in the inset because it was not physiologically motivated.

DTF peak levelling was intended to model the Negative Level Effect, which we hypothesized is a result of saturation of neural rate-level functions at high stimulus intensities. It was accomplished by leveling off spectral peaks at specified DTF ceiling levels. We examined the effect of peak levelling at ceiling levels of −5, 0, +5, +10, and +15 dB that were the same as those used as floor levels in notch filling. This process is illustrated for ceiling levels of 0 and +5dB in Fig. 2c. The inset panel shows a hypothetical abruptly saturating auditory nerve rate-level function that could produce a peak-levelled peripheral representation of a DTF spectral profile for a high-intensity stimulus.

Figure 3 shows the cumulative distribution of DTF magnitudes for the right ear of each of the five listeners across (linear) frequency and across locations ispilateral to the ear. Only ipsilateral-location DTFs were used in generating those distributions because vertical-plane localization has been shown to depend primarily on the DTF for the ear ipsilateral to the source (Macpherson and Sabin, 2007). The floor and ceiling values of −5 to +15 dB used in the notch-filling and peak-levelling manipulations spanned approximately the 10th to 95th percentiles of the distribution of ipsilateral-ear DTF magnitudes across frequency and location, although this varied slightly depending upon the characteristics of each listener’s DTFs. The median DTF magnitudes were ~5–7dB, which is close to the middle (+5-dB) value selected for the notch-filling and peak-levelling floor and ceiling. Thus notch filling and peak levelling with floor and ceiling values of +5 dB had approximately symmetrical effects on the DTFs in that they affected approximately equal numbers of frequency bins. Since notch filling at 0 dB affected bins below approximately the 20th percentile and peak-levelling at +10 dB affected bins above the 80th percentile, those two manipulations were also symmetrical in that they affected similar numbers of frequency bins.

In Experiment II, an alternative procedure was used to model the hypothesized degradation in the peripheral representation of DTF spectral features in brief, intense stimuli. The procedure was to reduce the spectral contrast in each DTF profile (which could be quantified by the maximum-to-minimum, or peak-to-notch, gain ratio in dB) by multiplying the gain (in dB) at each frequency by a constant <1. Such a compression of spectral contrast should affect peaks and notches in the DTF spectra equivalently. An example of this procedure is shown in Fig.2e, in which the thin line shows the normal DTF profile, the heavy dashed line shows the DTF with spectral contrast reduced by multiplying by a factor of 0.5 (50% of the original contrast), and the heavy solid line shows the DTF with spectral contrast reduced by multiplying by a factor of 0.25 (25% of the original contrast). The inset plot shows a hypothetical, slowly saturating neural rate-level function that could result in progressive reduction in the contrast of a DTF profile as stimulus level was increased. DTF sets were constructed with spectral contrast factors of 25, 50, 75, and 100%. The spectral contrast manipulation method also permitted expansion of the normal spectral cue amplitudes by choosing a scaling factor >1. DTF sets with contrast factors of 150, 200, 300, and 400% were also created. An example of a DTF created with a contrast factor of 150% is shown in Fig.2e (thin dotted line). The contrast-expansion manipulation was not physiologically motivated, and therefore is not represented in the inset plot.

We attempted to preserve natural binaural difference cues in all the manipulated DTF sets. To retain as much as possible the original interaural time-difference cues, the impulse responses used to synthesize the virtual auditory space stimuli were computed with an inverse Fourier transform of the altered spectral magnitudes combined with the phase spectra of the unaltered DTF filters. To preserve the overall interaural level-difference cues, the amplitudes of the resulting left- and right-ear impulse responses were adjusted to yield the original interaural level difference in dB for a wideband noise stimulus at each location. This did not preserve the interaural level difference at each frequency, but as a localization cue the overall level difference has been shown to be just as salient as the interaural level difference spectrum (Macpherson and Middlebrooks, 2002).

Our notch-filling and peak-levelling manipulations are similar to those used by Zhang and Hartmann (2010), but differ in that we used multiple floor and ceiling values to vary the strength of the manipulation, whereas those authors used a single common value equal to the RMS level of the spectrum. The contrast expansion of the DTFs, followed by attempted preservation of natural binaural difference cues and then restoration of the diffuse-field response, is similar in effect to the HRTF enhancement explored by Brungart and Romigh (2009) and Brungart et al. (2009). In that technique, the differences between HRTFs with common lateral angles were expanded in an attempt to improve vertical-polar localization. The expansion is also similar to the spectral sharpening employed by Zhang and Hartmann (2010), in which the DTF spectrum was convolved on a linear scale with a “Mexican-hat” function 525 Hz wide, and to the squaring of the HRTF magnitude spectrum described by Wightman and Kistler (1997), which corresponds directly to our 200-% contrast expansion condition.

The notch-filling, peak-levelling, and spectral-contrast adjustment manipulations were all performed on the DTFs on a linear frequency scale and prior to the transduction of the DTF-filtered stimuli by the peripheral auditory system. This is of course the reverse of the hypothesized sequence of events leading to the Level and Negative Level effects. To estimate the effect of those manipulations on the peripheral representations of the stimulus spectra, we computed, for each listener, target location, and DTF manipulation, excitation patterns (EPs) for a 55-dB SPL, 0.5–16-kHz flat-spectrum noise signal filtered by the corresponding ipsilateral-ear manipulated DTF. EPs were computed using a bank of symmetrical ro-ex filters with 64 logarithmically spaced center frequencies per octave spanning the frequency range from 0.5 to 16 kHz. The equivalent rectangular bandwidth of each filter was determined by its center frequency as specified by Glasberg and Moore (1990). The EP computation only accounted for the directionally varying acoustics of the DTFs, and did not include the transfer functions of the ear canal or middle ear. The right-hand panels of Fig.2 show, for one listener and one location, the EPs resulting from the notch-filling, peak-levelling and spectral-contrast reduction or expansion DTF manipulations illustrated in the left-hand panels. By inspection, it is evident that the DTF manipulations had the intended effects on the EPs; DTF notch filling affected primarily notches in the EPs, peak levelling affected primarily peaks, and DTF spectral-contrast alterations enlarged or reduced excitation-level differences between frequencies while preserving the overall shape of the EP.

2.4. Stimuli and locations

The target stimuli filtered by the manipulated and unmanipulated DTFs described above were bursts of flat-spectrum, random-phase noise with a bandwidth of 0.5–16 kHz. Each burst had a duration of 100 ms that included 20-ms, raised-cosine onset and offset ramps. Targets were presented at a mean level equivalent to 55 dB SPL in free-field, and the level was roved from trial to trial by ±5 dB. Stimuli were presented over circumaural headphones (Sennheiser HD 265) at a sampling rate of 50 kHz. The diffuse-field equalization of the headphones restored an approximation of the non-directional component of the HRTFs removed in the computation of the DTFs.

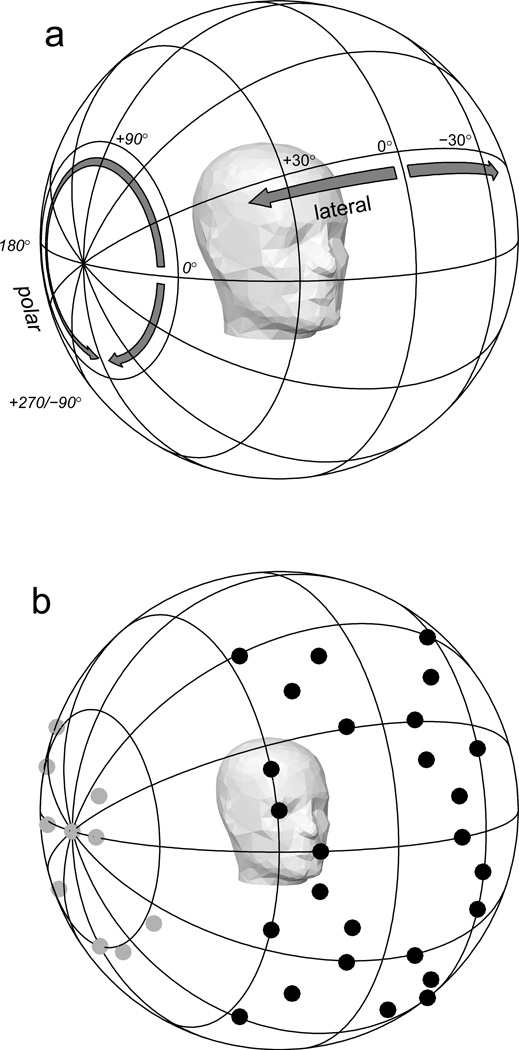

Target and response locations were described in the single-pole, lateral- and polar-angle coordinate system as shown in Fig. 4a. Lateral angle is defined as the angle between a location and the vertical median plane, and ranges from −90 to +90 degrees, with positive values to the listener’s right and a value of 0 on the vertical median plane. Polar angle is defined as the angle of rotation about the interaural axis, with 0 degrees corresponding to locations on the front horizontal plane, the range −90 to +90 degrees corresponding to the frontal hemisphere, and the range +90 to +270 degrees to the rear hemisphere.

Figure 4.

a) Lateral- and polar-angle coordinate system. Lateral angle is the deviation to the left or right from the median sagittal plane. Polar angle is the angle of rotation around the interaural axis, with 0 degrees polar angle in front, +90 degrees overhead, and 180 degrees to the rear. b) Stimulus locations. Stimuli synthesized with modified and unmodified DTFs were presented from 52 test locations: 26 in the front hemisphere (shown by black symbols) and 26 in the rear (not shown). Stimuli synthesized with unmodified DTFs were also presented from 26 lateral locations: 13 on the right (shown by gray symbols) and 13 on the left (not shown).

The set of possible stimulus locations consisted of 52 near-midline test locations and 26 lateral locations. The test locations were comprised of 26 locations distributed between −30 to +30 degrees lateral angle and −60 to +60 degrees polar angle in the front hemisphere (shown by the black symbols in Fig. 4b) and a corresponding set of 26 locations between 120–240 degrees polar angle in the rear hemisphere. The lateral locations consisted of 13 locations in the right hemisphere at lateral angles greater than 40 degrees (shown by the gray symbols in Fig. 4b) and a corresponding set of 13 in the left hemisphere. The lateral locations were included to provide a full range of lateral angles in each block of trials, but because small changes in location can correspond to very large changes in polar angle for such locations near the interaural axis, responses to stimuli presented from those locations were not analyzed.

Experiment I involved characterizing each listener’s localization performance with 11 different test sets of DTFs: one unmanipulated set, five notch-filled sets with different floor values, and five peak-levelled sets with different ceiling values. Each block of trials consisted of 130 stimulus presentations. Of these, 78 filler trials were synthesized with the listener’s normal, unmanipulated DTFs and presented once from each of the 52 test locations and once from each of the 26 lateral locations. These faithfully synthesized stimuli comprised 60% of the trials, and were included to promote a uniform response strategy for manipulated and unmanipulated stimuli. Responses to the filler trials were not analyzed, but responses to equivalent stimuli from the unmanipulated-DTF test set were. The remaining 52 trials consisted of one presentation from each of the near-midline test locations using a left-right pair of DTFs selected from among the 11 DTF test sets. Trial blocks were composed in such a way that over 11 different blocks, each combination of test-location and DTF manipulation was presented once. Notch-filled, peak-levelled, and unmodified test-set stimuli were interleaved within each block. Each listener completed four repetitions of the entire stimulus set to provide four responses per DTF-set/location combination over a total of 44 blocks of trials.

The trial blocks for Experiment II were constructed similarly to those for Experiment I. The stimuli used nine different test sets of DTFs: one unmanipulated set, three contrast-compressed sets, and four contrast-expanded sets. Nine blocks of trials were therefore required to yield one localization response for each DTF test set at each test location. Each listener repeated the nine blocks four times to provide four responses for each combination of location and DTF test set for a total of 36 blocks of trials.

In each block of 130 trials, stimuli were presented in a randomly shuffled order. Each block took approximately 10 minutes to complete. Listeners typically completed six blocks, separated by short breaks, within a 90-minute laboratory session. All blocks for Experiment I were presented prior to beginning Experiment II.

2.5. Response procedures

The virtual auditory space stimuli were presented over headphones while the listener stood at the center of the darkened anechoic chamber in which their DTFs had been measured. The listeners indicated the apparent location of a target by turning their body and tilting their head to orient their face in the appropriate direction. The following procedure was used to constrain the listener’s head orientation at the time of stimulus presentation. At the beginning of each trial, the listener oriented toward a light-emitting diode (LED) positioned at eye level 60 cm away. The listener initiated each trial by pressing a hand-held button, which also triggered an initial measurement of the listener’s head orientation by a head-mounted electromagnetic tracking device (Polhemus Fastrak). If the head orientation deviated from the LED fixation direction by >5 degrees either horizontally or vertically, the LED began to blink, indicating that the listener should adjust his or her head position to achieve fixation. Once this was achieved, the LED was extinguished, and after 500ms, head position measured again. If correct head orientation had been not been maintained, the LED again began to blink and the head-adjustment phase was repeated. Otherwise the stimulus was presented. After hearing the stimulus, the listener oriented toward its apparent location, then pressed the button again, which triggered a final measurement of head orientation. This orientation measurement constituted the listener’s response.

2.6. Training and practice procedures

Prior to formal data collection, each listener was given a demonstration, instruction, and practice in performing the head-pointing task. In an attempt to minimize systematic undershoot in vertical head angle that can result from the tendency of listeners to use eye movements in conjunction with the head to orient to an elevated target, the head training procedure described by Macpherson and Middlebrooks (2000) was employed. Briefly, the listener attempted to orient to visual targets illuminated at randomly chosen locations varying in lateral and polar angle, and after indicating their orientation response via a button press, the pointing error was demonstrated by moving the target to the response location. In the first practice session, listeners completed 10 minutes of head training, and thereafter each practice or data collection session began with 3 minutes of this procedure. Over the course of two or three practice sessions in the darkened anechoic chamber, listeners completed three 65-trial blocks with free-field, wideband noise targets and six 108-trial blocks with virtual wideband targets. No trial-by-trial feedback for auditory targets was given during the practice or formal test sessions, but listeners were informed about, and encouraged to correct, systematic biases in their responses following each block of trials in practice sessions.

3. Results

3.1. Data analysis

For each DTF test set, both manipulated and natural, each listener’s localization performance was quantified by computing values for three types of dependent variable following the methods used by Sabin et al. (2005): response/target gain, the proportion of quasi-veridical responses, and the variability of quasi-veridical responses. A quasi-veridical response was defined as one falling within 45 degrees of the regression line fit in the computation of a response/target gain, and the variability of those responses quantified their scatter about the regression line.

The dependent variable values were computed for the polar-angle and lateral-angle components of listeners’ responses, and performance in the vertical dimension was quantified separately for front- and rear-hemisphere targets. For consistency with the methods of previous studies, these values were computed using the lateral- and polar-angle coordinates directly; no normalization was applied, for example, to convert from polar angle to arc length via multiplication by the cosine of the lateral angle. The limited range of test-set lateral angles was chosen by design to minimize the effect on the results of the compression of arc length for a given polar angle at more eccentric lateral angles.

Subsets of the data from Macpherson and Middlebrooks (2000) and Sabin et al. (2005) were subjected to the same analysis for purposes of comparison. The data set from Sabin et al. (2005) was restricted to targets within the lateral- and polar-angle ranges used in the present study. The results of these analyses of previous data are plotted in Fig. 1.

For each case (a combination of DTF test set, target hemisphere, and listener), polar-angle gain was computed as the slope, gpol, of the regression line fit between the physical target polar angle, ϕTARG, and the response polar angle, ϕRESP. Systematic offset in responses was captured by the constant regression coefficient (ϕ0,pol;

| (1) |

A polar-angle gain close to 1 indicates accurate localization performance in the vertical dimension, and a value near 0 indicates severe compression of the apparent elevation of the stimulus toward the horizontal plane. In the latter situation, targets above the horizontal plane appear to originate from locations lower than the physical location, and targets below the horizontal plane appear higher. Separate gains, gpol,F and gpol,R, were computed for front- and rear-hemisphere targets. Responses falling in the incorrect hemisphere (i.e. front-to-rear or rear-to-front reversals) were excluded entirely from the gain computations rather than being mirrored into the correct hemisphere. Polar-angle gain analysis for an example data set is shown in Fig. 5a.

Figure 5.

Example analysis for listener S160 in the 10-dB-ceiling peak-levelled condition (Sec. 3.2). a: response polar angle versus target polar angle for the test locations. The regression lines fit in the computation of polar-angle gain are shown for front- and rear-hemisphere data. Responses are classified as quasi-veridical (•) or non-quasi-veridical (×), the latter being >45 degrees from the regression lines. b: response lateral angle versus target lateral angle for the same data set. The regression line fit in the computation of lateral-angle gain is shown.

In four cases, polar-angle gain was not computed because fewer than 20 non-reversed responses remained and these yielded unreliable regression coefficients. That occurred only for front-hemisphere targets for listener S164 in the two most extreme notch-filled conditions (floor values of +10 and +15 dB) and the two most extreme peak-levelled conditions (ceiling values of 0 and −5dB). In those cases, the vast majority of responses were reversed to the rear hemisphere, leaving insufficient data for reliable estimation of the front polar-angle gain and variability. In addition, no rear-hemisphere polar-angle gain (gpol,R) was computed for any DTF test set for two of the five listeners (S159 and S165). Those two listeners exhibited inaccurate localization of rear-hemisphere targets even for the natural DTF test set, making any interpretation of the effects of the DTF manipulations problematic. Their performance with front-hemisphere targets was similar to that of the other listeners.

Lateral-angle gain, glat, was computed similarly to polar-angle gain, and was defined as the slope of a regression line fit between physical target lateral angles and response lateral angles. Only responses to the test-set locations, which had lateral angles between −30 and +30 degrees, were used to determine glat, and as in the computation of the polar-angle gains, front/rear reversed responses were excluded entirely. In the example shown in Fig. 5b, the lateral-angle gain is slightly greater than 1, indicating that the listener’s responses tended to slightly overshoot the eccentricity of the targets.

In each case, the proportion of quasi-veridical responses (p(QV)pol,F, p(QV)pol,R, or p(QV)lat), was used to characterize the presence or absence of large deviations from the performance described by a target/response regression line. For polar angle, non-quasi-veridical responses consisted primarily of front-to-back or back-to-front reversals, and, much less often, large polar-angle errors within the same hemisphere as the target location. If the proportion of quasi-veridical responses is close to 1, the proportion of responses far from the regression line is small, typically indicating that there are few reversals. A value closer to 0 indicates that the majority of responses exhibit large polar-angle errors. For lateral angle, non-veridical responses consisted of large errors; there was no identifiable subset of left/right reversed responses for any listener. In the example shown in Fig. 5a, quasi-veridical responses are plotted with circles, and non-quasi-veridical responses with x’s. In the four cases for listener S164 for which front polar-angle gain was not computed, p(QV)pol,F was computed simply as the rate of correct-hemisphere responses. p(QV)pol,R was not computed for any DTF test set for listeners S159 and S165 due to their poor localization of rear-hemisphere targets.

Finally, for each case, the variability (σpol,F, σpol,R, or σlat) of quasi-veridical responses was computed as the root-mean-square value of their deviations from the polar- or lateral-angle regression lines. That yielded a value in degrees quantifying the scatter of the responses. Variability was not computed for those cases for which polar-angle gains were not computed.

The three dependent measures derived from each case were subjected to further statistical analyses as described below. When sets of multiple comparisons were performed, we employed the False Discovery Rate procedure (modified Bonferroni, Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) to control the family-wise probability of Type I errors.

3.2. Experiment I: Distortion of spectral notches or peaks

3.2.1.Qualitative description of results

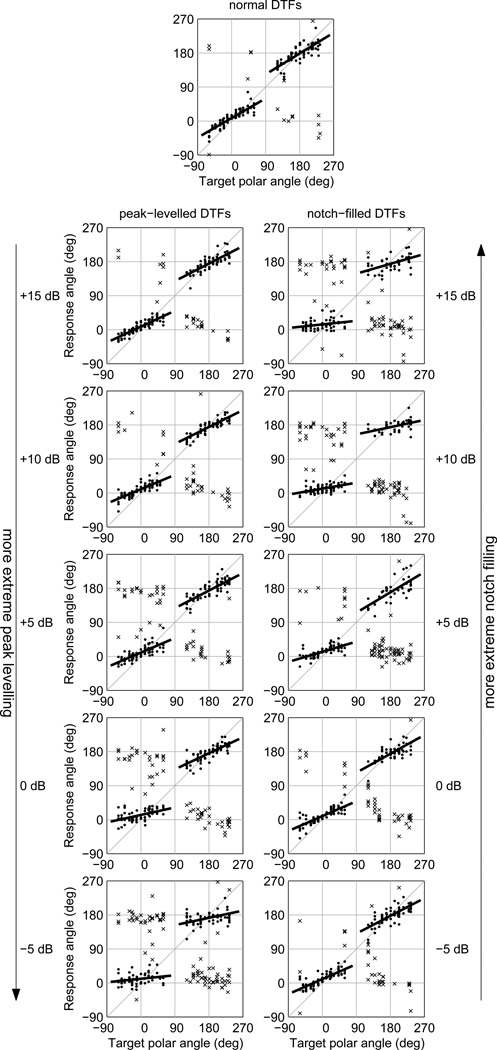

Plots of response polar angle versus target polar angle for each set of DTFs in Experiment I for one listener (S160) are shown in Fig. 6. The top centered panel shows the data for the unmodified DTF set, the right column shows the data for the notch-filled DTF sets, and the left column the data for the peak-levelled sets. Each panel also includes the regression lines fit in the computation of the polar-angle gains in the front and rear hemispheres. Quasi-veridical and non-quasi-veridical responses are plotted with the same symbol in this figure.

Figure 6.

Response polar angle versus target polar angle for listener S160 in notch-filled and peak-levelled DTF conditions (Experiment I). Top centered panel: data for unmodified DTFs. Right column of panels: data for notch-filled DTFs, with floor values increasing from −5dB (bottom) to +15 dB (top). Left column of panels: data for peak-levelled DTFs, with ceiling values decreasing from +15 dB (top) to −5dB (bottom). The regression lines fit to the non-reversed responses in front and rear hemispheres are shown. Symbols for quasi-veridical (•) and non-quasi-veridical ×) responses match those in Fig. 5.

For the unmodified DTF set (top centered panel), most responses were clustered around the regression lines, indicating a high proportion of quasi-veridical responses. A handful of responses to front-hemisphere targets fell in the rear hemisphere (front-to-back confusions). Back-to-front confusions are shown by the points near the negative diagonal of the plot in the lower right-hand quadrant, and were somewhat more numerous for this listener than were front-to-back reversals. The polar-angle gain for both front- and rear-hemisphere targets was somewhat below 1 for this listener; using the head-orienting response procedure, it is not uncommon for listeners’ responses to systematically undershoot the true target locations even for faithfully synthesized stimuli. The infrequency of large polar-angle errors (such as front/rear reversals) observed for the unmodified DTFs was consistent across listeners, which suggests that our virtual auditory space synthesis techniques were adequate and that low vertical gain in the control condition was due to the listeners’ response strategies.

The data for the notch-filled DTF sets (right column of panels) show a progressive decrease in polar-angle gain and increase in reversals as the notch-filling floor was raised, the manipulation used to simulate decreasing stimulus level near threshold. At the lowest floor value (−5dB), for which the distortion of the DTFs was mildest, the pattern of responses was similar to that for the unmodified DTFs (top centered panel). For the most extreme notch-filling case (+15dB floor), the slopes of the regression lines were markedly shallower and the occurrence of reversals more common. For the peak-levelled DTF sets, a similar pattern of decrease in polar-angle gain and increase in the proportion of quasi-veridical responses is apparent in the left-hand column of panels in Fig. 6 as the peak-levelling ceiling was reduced from +15dB (mildest levelling) to −5dB (most extreme levelling). Reduction in peak-levelling ceiling was the manipulation used to simulate increasing stimulus level for brief sounds.

3.2.2. Polar-angle gain, p(QV), and variability measures

Target/response gains, g, the proportions of quasi-veridical responses, p(QV), and response variability, σ, were computed for each listener, for each DTF test set and for frontand rear-hemisphere targets with the exceptions noted above. All five listeners in Experiment I showed similar patterns of polar-angle gain across the stimulus groups, and we therefore computed mean values of the three variables across listeners. To correct for systematic inter-listener differences in gain, and prior to averaging, the gain values for each listener were normalized by dividing by the gain attained for the natural-DTF stimuli. Front- and rear-hemisphere polar-angle gains were normalized independently. No normalization was applied to the p(QV) or σ data.

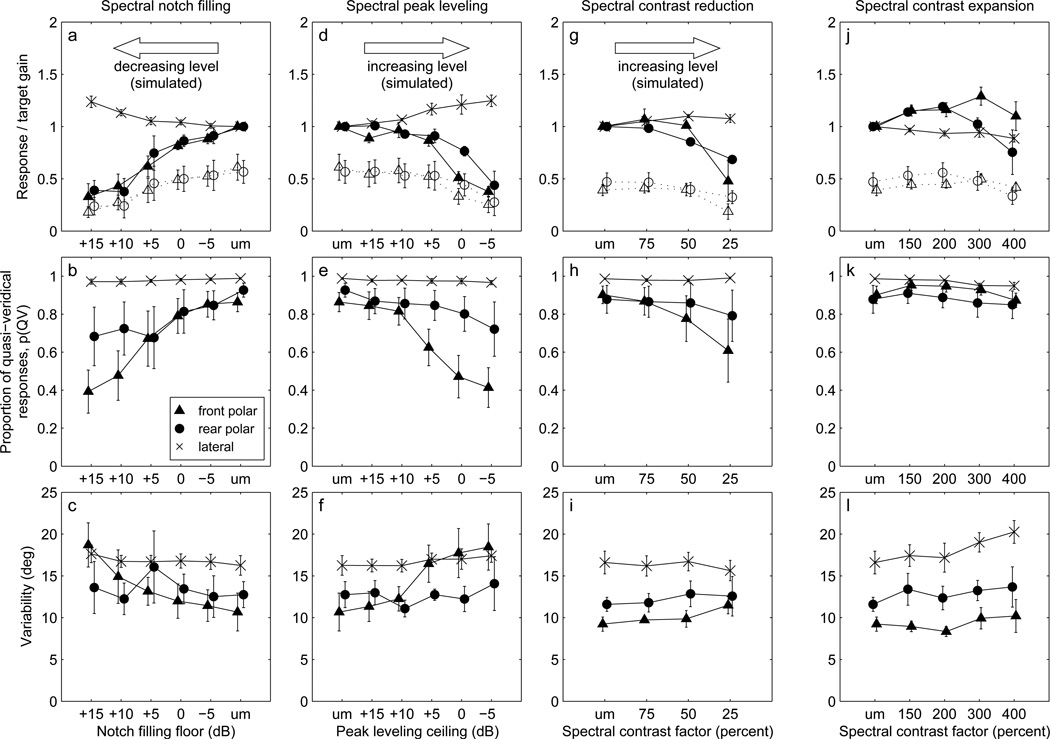

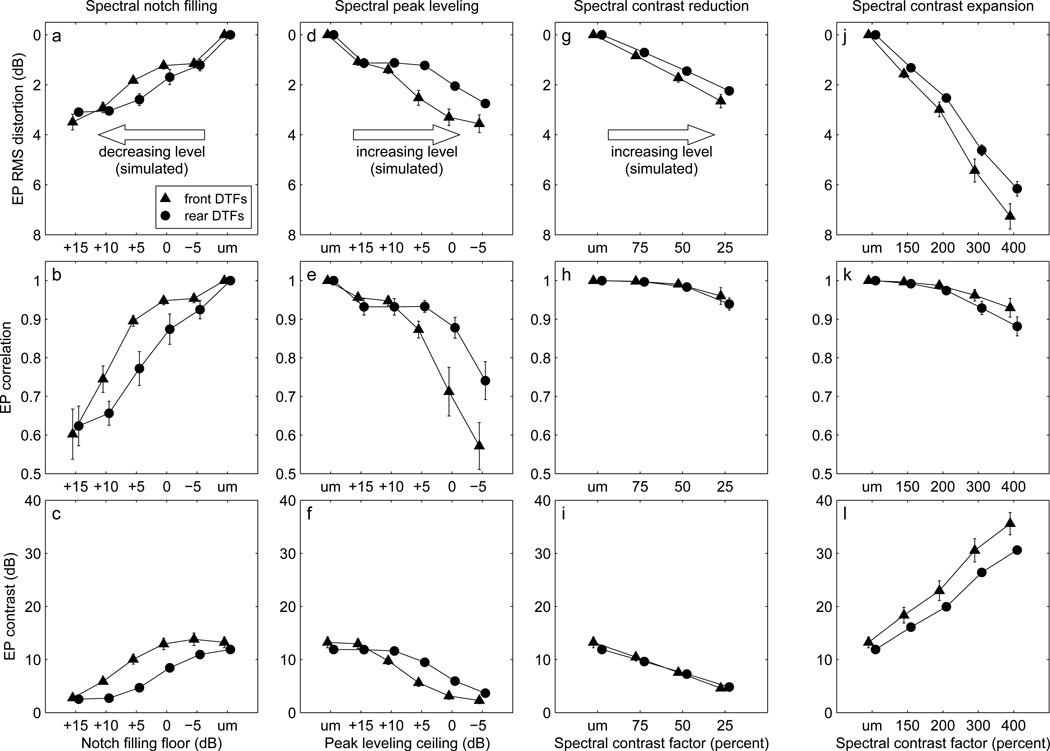

Mean gain (normalized and un-normalized), p(QV), and σ values for the DTF test sets of Experiment I are presented as a function of filling or levelling floor and ceiling values in the first (notch-filling) and second (peak-levelling) columns of Fig. 7 (panels a–c and d–f, respectively). Note that the floor/ceiling axis is ordered to better represent the correspondence between the degree of filling or levelling and simulated stimulus level. The top-row panels show polar- and lateral-angle gains, the middle-row panels show p(QV), and the bottom-row panels show variability, σ. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means. At the right extremes of the filling floor value scales are plotted the data for the unmodified (“um”) DTFs, which correspond to an infinitely low notch-filling floor (simulating a presentation level well above threshold). Similarly, those same data are plotted at the left extremes of the peak levelling scales, representing an infinitely high peak-levelling ceiling (simulating a presentation level well below saturation). The unmodified-DTF values plotted in the notch-filling and peak-levelling columns are therefore identical, and for normalized gains are exactly equal to 1. The un-normalized polar-angle gains (plotted with open symbols and dashed lines in Fig. 7 panels a and d) are markedly lower than 1, as noted in Sec.3.2.1 above, but inspection of the standard error bars reveals that the normalization successfully reduced inter-listener variability in most cases.

Figure 7.

Mean polar- and lateral-angle gains, proportions of quasi-veridical responses, and variability for notch-filled (panels for notch-filled (a–c), peak-levelled (d–f), contrast-reduced (g–i), and contrast-expanded (j–l) DTF sets as a function of manipulation strength. Error bars show the standard error of the mean across listeners. “um” on the horizontal axis indicates the data for the unmodified DTF sets. Symbols for front-polar, rear-polar, and lateral-angle data are slightly offset horizontally for clarity. Symbols: front polar angle (normalized, ▲ un-normalized, ○), rear polar angle (normalized, •; un-normalized, ○), lateral angle (normalized, ×).

For the notch-filled DTF sets (Fig. 7a–c), the mean normalized polar-angle gain in the front and rear hemispheres decreased monotonically as the notch-filling floor was increased from −5dB to +15 dB, simulating decreasing presentation level. A set of paired t-tests comparing the front- and rear-hemisphere polar-angle gains at each floor value indicated that there were no significant front/rear differences in gain. Even the mildest notch filling (-5-dB floor) resulted in a significant decrease in normalized polar-angle gain to a value of 0.89 from 1 for the unmodified DTFs (t(7)=2.85, p<0.05; front- and rear-hemisphere cases pooled). Even so, the reductions in polar-angle gain were modest until the floor value was increased to +10 dB, which produced gains <0.5.

For the peak-levelled DTF sets (Fig. 7, d–f), the polar-angle gain decreased more gradually than for notch-filling as the peak-levelling ceiling was reduced. A set of paired t-tests revealed no significant front/rear differences in gain. For the mildest peak-levelling (+15-dB ceiling), the reduction in gain to 0.93 was not statistically significant (t(7)=1.94, p>0.4, front- and rear-hemisphere cases pooled). As for notch-filling, polar-angle gain decreased dramatically for the two most extreme ceiling limits (0 and −5 dB), but to values somewhat higher than those for the most extreme notch-filling conditions.

We compared the effect on localization performance of mild notch-filling and mild peak-levelling. Pooling front- and rear-hemisphere polar gain values across listeners, we computed the gain-versus-floor and -ceiling slopes of linear fits over the −5 to +5-dB notch-filling range and over the 5 to 15-dB peak-levelling range. The absolute values of the slopes were 0.023/dB and 0.005/dB, respectively, and the difference in the slopes was statistically significant (t(44) = 1.83; p < 0.05), indicating that mild notch filling was more detrimental to gain than was mild peak-levelling.

The proportion of quasi-veridical responses, p(QV), for un-modified DTFs (mean of 0.89 over listeners, front/rear, and filled/leveled cases, Fig. 7 b and e) was similar to that for the 250-ms freefield targets used by Sabin et al. (2005, Fig. 1b). The proportion decreased as the notch-filling floor was raised or the peak-levelling ceiling was lowered, indicating worsening performance. The range in p(QV) for rear-hemisphere targets was less than that for front-hemisphere targets because most listeners experienced a greater increase in front-to-back confusions than in back-to-front confusions as the DTFs were progressively distorted. Marked differences between the notch-filling and peak-levelling manipulations were not observed in the p(QV) data. Particularly for the front-hemisphere, these data followed a pattern which was the mirror-image of that for notch filling, and for both hemispheres, changed over a range equal to that for notch filling. Pooling front- and rear-hemisphere data, an analysis was performed of the slopes of p(QV)-versus-floor and -ceiling linear fits over the same mild-manipulation filling and levelling ranges used above for polar angle gain. Absolute slopes were 0.018/dB and 0.015/dB for filling and levelling, respectively, and the slope difference was not statistically significant (t(44)=0.23; p>0.8). Thus, notch-filling and peak-levelling appeared to affect p(QV) similarly.

The variability of quasi-veridical responses, σ, for un-modified DTFs (mean of 11.1 degrees over listeners, front/rear, and filled/leveled cases, Fig. 7 c and f) was similar to that for the 250-ms freefield targets used by Sabin et al. (2005) (Fig. 1c). The variability measure increased systematically with more extreme notch filling or peak levelling only for the polar angle response component for front-hemisphere targets. For those targets, polar-angle variability increased as the notch-filling floor was increased (Fig. 7c, significant linear trend, F(1,24) = 6.32, p = 0.020) and also as the peak-levelling ceiling decreased (Fig. 7f, significant linear trend, F(1,24) = 8.90, p < 0.01). No other statistically significant linear trends were found for the variability measure, and the significant changes that were found were likely due to a single subject, as discussed below (Sec. 3.4).

3.2.3. Lateral-angle measures

For both notch-filling and peak-levelling manipulations, mean normalized lateral angle gains increased in the most extreme manipulation conditions, which were intended to simulate low- and high-intensity stimulus presentation (Fig. 7 a and c). In the case of notch-filling, that increase corresponds to the lateral-angle gain “bump” seen in the low-intensity data of Sabin et al. (2005) and Vliegen and Van Opstal (2004) (Fig. 1a and Fig. 1d, respectively). A mild increase in lateral angle gain is also visible in the data of Macpherson and Middle-brooks (2000) that show the negative level effect for polar-angle gain (Fig. 1e). There was no systematic variation of lateral-angle p(QV) or variability with notch-filling or peak-levelling floor or ceiling limits.

3.3. Experiment II: Reduction or expansion of spectral contrast

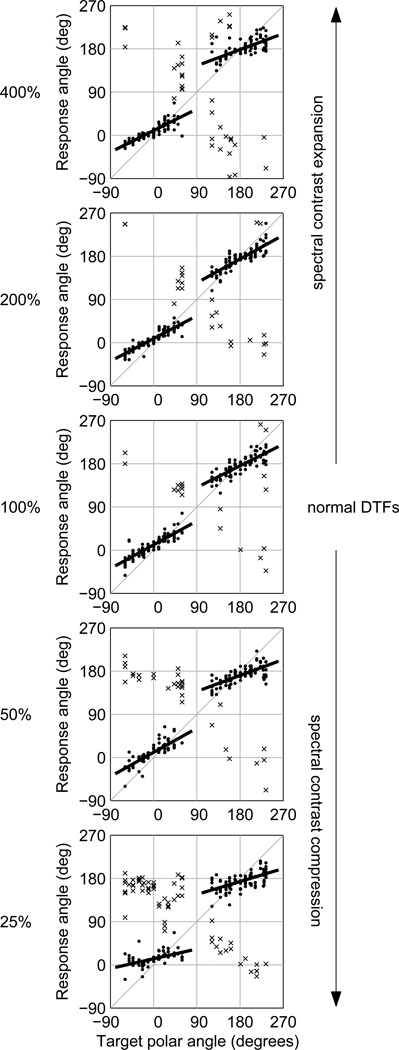

3.3.1. Qualitative description of results

Plots of response polar angle versus target polar angle for selected sets of reduced contrast and expanded contrast DTFs are shown in Fig. 8 for one listener (S160). From bottom to top, the four panels show the data for the 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400% contrast factors. Thus, the middle panel shows the data for the unmodified DTFs (100% contrast factor), the lower two panels show the data for reduced contrast conditions, and the upper two panels show the data for expanded contrast conditions. All of the panels indicate performance similar to that for the unmodified DTFs with the exception of that for the most compressed DTF set (25% contrast factor), which shows a marked increase in non-quasi-veridical responses (primarily front-to-rear and rear-to-front reversals) and a significant reduction in polar-angle gain. The data for the 50%-compressed conditions do show a slight increase in reversals, but no decrease in polar-angle gain.

Figure 8.

Response polar angle versus target polar angle for listener S160 in selected contrast-compressed and expanded DTF conditions (Experiment II). From bottom to top, 25, 50, 100 (normal), 200 and 400% contrast factors. The regression lines fit to the non-reversed responses in front and rear hemispheres are shown. Symbols for quasi-veridical (•) and non-quasi-veridical (×) responses match those in Fig. 5.

3.3.2. Gain, p(QV), and variability measures

All four listeners exhibited similar patterns of performance across conditions, and therefore mean (normalized) polar-angle gain, p(QV), and σ were computed across listeners as in Experiment I. The results are plotted as a function of spectral contrast factor in Fig. 7 panels g–i (contrast reduction, third column) and j–l (contrast expansion, right-hand column). The values plotted at the “um” contrast factor (unmodified, i.e. 100% contrast factor) are those for the normal DTF set, and in the case of the normalized gains have a value of exactly 1. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean across listeners.

Polar- and lateral-angle gain values are plotted in Fig. 7 g and j, respectively. The unnormalized polar-angle gain for the unmodified DTFs had a mean value across listeners and front/rear cases of 0.43. As for the notch-filling and peak-levelling data, the gain normalization procedure reduced the inter-listener variability in most cases. A set of paired t-tests indicated no statistically significant differences between front- and rear-hemisphere normalized gain at any spectral contrast factor. A second set of of t-tests indicated that the mean normalized gain (front- and rear-hemisphere cases pooled) differed significantly from 1 only at contrast factors of 25, 150, and 200%.

When spectral contrast was reduced, mean polar-angle gain (Fig. 7g) showed a pattern consistent with that observed in the raw data of listener S160. Normalized gain for these targets remained close to 1 except for the most severe spectral contrast compression (25%), for which the mean gain was 0.57. For contrast expansion, mean normalized polar-angle gain (Fig. 7j) increased modestly to 1.15 and 1.17 at contrast factors of 150% and 200%, respectively. Those small improvements of absolute accuracy (higher un-normalized gain) are similar to the improvements in localization performance observed by Brungart and Romigh (2009) and Brungart et al. (2009) when employing their similar HRTF enhancement technique. As noted above, at contrast factors of 300% and 400%, neither front/rear gain differences nor devations from a normalized gain of 1 were statistically significant.

As spectral contrast was reduced, the proportion of quasi-veridical responses, p(QV), for front-hemisphere targets (Fig. 7h, triangles) declined monotonically, indicating that, at compression factors of 50 and 75%, the number of front-to-back reversals increased even though polar-angle gain did not decrease. For rear-hemisphere targets, (Fig. 7h, circles), p(QV) varied little as spectral contrast was reduced. As found for the notch-filled and peak-levelled DTF sets in Experiment I, for most listeners, the number of front-to-back reversals increased more rapidly than did the number of back-to-front reversals as spectral cues were degraded. Spectral contrast expansion had no obvious effect on p(QV) for front- or rear-hemisphere targets (Fig. 7k). Response variability, σ, did not vary markedly with either reduction or expansion of spectral contrast apart from an increase with increasing expansion for lateral angle (Fig. 7 i and k).

3.4. Interpretation of computed polar-angle gain and variability

Although all listeners’ polar-angle gains were affected similarly by the DTF manipulations used in Experiments I and II, examination of the gain metric alone is insufficient to confirm that all listeners exhibited the compression of elevation visible in Fig. 6 and Fig. 8; other qualitatively different response patterns could also result in declining polar-angle gain. Joint consideration of gain and σ, the variability of quasi-veridical responses, can however indicate the degree to which responses systematically collapsed toward the horizon.

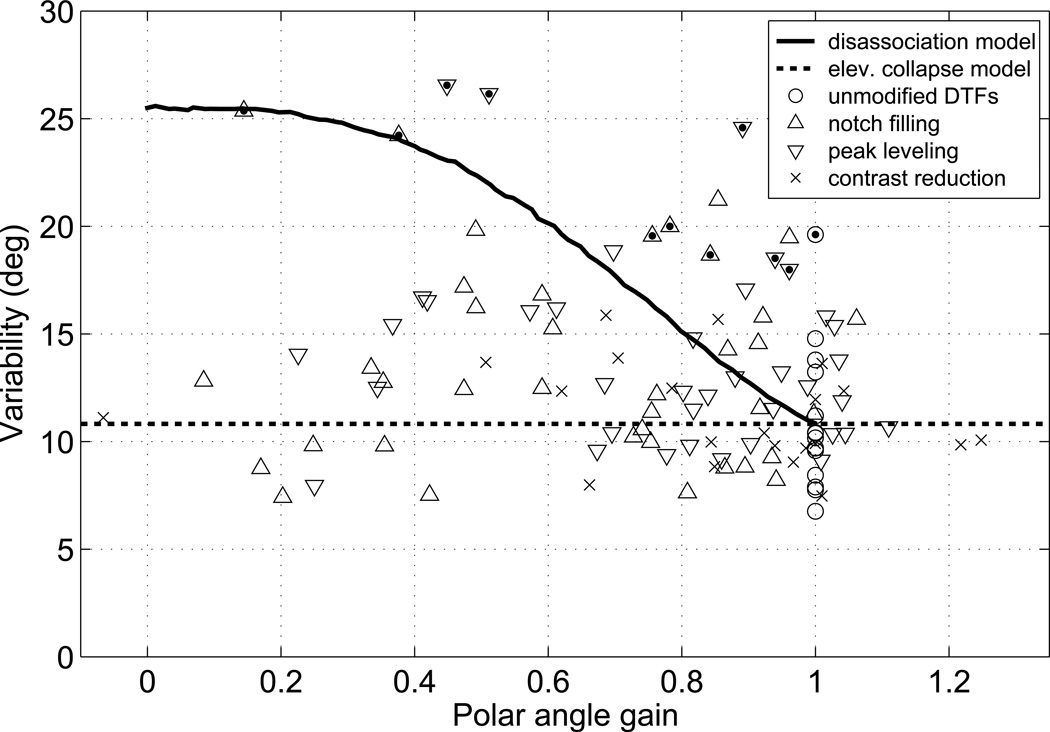

Figure 9 shows, for each combination of DTF test set, target hemisphere, and listener in Experiments I and II, variability plotted as a function of the normalized polar gain. The data for listener S159 (who participated only in Experiment I; dotted triangle symbols) appeared to follow a different pattern from the others’.

Figure 9.

Relation of variability and polar-angle gain: individual listeners’ data and model predictions. Variability, σ, is plotted as a function of normalized polar-angle gain for each combination of DTF test set, target hemisphere, and listener in Experiments I and II. Symbol-shape indicates the type of DTF manipulation applied. Dots (•) fill the outlying data points of listener S159, who participated only in Experiment I. Solid line (—): prediction of a disassociation model, in which listeners’ responses are unrelated to the stimulus on some proportion of trials. Dashed line (- -): prediction of the elevation collapse model, in which responses become systematically biased toward the horizon.

To interpret these data, we considered three response models. First, under elevation collapse, responses become systematically biased toward the horizon, in which case variability should remain constant while gain declines (Fig. 9, dashed line). Second, under scatter increase, listeners’ responses become more variable, but the underlying systematic linear relation between response and target is unchanged. In this case, although the correlation between target and responses would decrease and variability increase, the expected value of the computed gain would not change; the slope or gain derived from a least-squares linear regression is an unbiased estimator of the true gain, the expected value of which is unaffected by correlation (Hays, 1988). The data in Fig. 9 clearly did not conform to this model, which predicts gains of ~1 in all cases. Finally, target/response disassociation would result in declining computed gain without true elevation collapse if listeners continued to utilize the full range of possible response elevations, but began to generate their responses at random as DTFs became distorted. In the limiting case in which there was no association between actual and perceived/reported polar angle, the expected gain would be 0, but the scatter of responses about the regression line would be much larger than that produced if the range of elevation responses had collapsed toward the horizon. Thus under the disassociation model, variability should increase as gain declines.

To examine the effect on gain of varying degrees of target/response disassociation, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation in which an underlying polar-angle gain of 1 was assumed and normal-DTF responses were generated by adding to the target elevations on each trial a random value drawn from a zero-mean normal distribution with a standard deviation of 10.9 degrees. That value was the mean of the σpol,F and σpol,R values we observed across listeners and the unmodified-DTF conditions in Experiments I and II (Fig. 7). To match the computation of gains and variabilities from the behavioral data, each simulated data set consisted of responses to four repetitions of the 26 front-hemisphere test locations. Varying degrees of target/response disassociation were obtained by selecting at random a specified proportion of the trials and shuffling their responses. We varied the shuffled proportion from 0 (no disassociation) to 1 (full disassociation), and for each, conducted 1000 runs of the simulation. From each set of runs, we estimated the expected value of the computed gain and of the variability of the responses lying withing 45 degrees of the the resulting regression line (i.e., of the “quasi-veridical” responses).

Expected gain declined linearly from 1 to 0 as the proportion of dissociated trial increased from 0 to 1. The relationship between gain and variability is plotted with the solid line in Fig. 9. At an expected gain of 1, the expected variability was slightly below the simulation scatter value of 10.9 degrees because the quasi-veridical criterion eliminated some highly deviant, but rare responses. At a gain of 0, which was generated when there was complete target/response disassociation, the expected variability rose to ~26 degrees. This is consistent with a uniform distribution of responses across the ±45-degree range around the 0-slope regression line because the standard deviation of such a distribution is , which corresponds to a value of 25.98 degrees for Δ = 90 degrees. This asymptotic value was independent of the choice of simulation scatter parameter.

It is evident that only the data of listener S159 approximate the predictions of the disassociation model. For the other listeners, variability did not increase with decreasing gain, and remained well below the value predicted by the disassociation model. We therefore conclude that true elevation collapse, rather than target/response disassociation, best explains the responses of the majority of the listeners. This analysis also suggests that the significant rise in variability observed for extreme notch-filling and peak-levelling conditions (Fig. 7) was caused by S159’s responses alone.

3.5. Excitation pattern distortion and polar-angle gain

We quantified the effect of the DTF manipulations on stimulus excitation patterns in the high-frequency range from 4–16 kHz using three metrics: EP RMS distortion, EP correlation, and EP contrast. Prior to computing these metrics, each EP was normalized by subtracting from it the EP for a flat-spectrum noise unfiltered by any DTF. Had

The EP RMS distortion was the root-mean-square difference in dB between the normalized excitation patterns for the stimuli generated with unmodified and unmodified DTFs. The EP correlation was the Pearson product-moment correlation between unmodified and modified normalized excitation patterns. The distortion and correlation measures were computed over the logarithmic frequency scale of the EPs. The EP contrast was simply the difference in dB between the maximum and minimum normalized excitation levels over the 4–16-kHz range. The normalization of the EPs served to remove the positive slope in the EPs caused by the increase of filter ERBs with frequency, which otherwise would have inflated the correlation and contrast values. Even if the EP computation had included the effects of the ear canal and middle ear, the normalization procedure would have largely eliminated them.

The values of each metric for each DTF manipulation were averaged over listeners and locations separately for front- and rear-hemisphere DTFs. The resulting mean values are plotted in Fig. 10, which is organized identically to Fig 7. For each metric, the orientation of the vertical axes of the plots was selected such that values for the least distorted DTFs in the notch-filling, peak-levelling, and contrast reduction conditions were near the top. That is, lower EP RMS distortion, higher EP correlation, and higher EP contrast values appeared towards the top of each plot. For the contrast expansion condition, EP contrast increased above the values for the unmanipulated stimuli with increasing contrast factor (panel l, bottom-right)

Figure 10.

Excitation pattern quality metrics as a function of DTF manipulation strengths. Top row: EP RMS distortion; middle row: EP correlation; bottom row: EP contrast.

For the notch-filling and peak-levelling conditions, the relationship between all three metrics and the strength of the DTF manipulations roughly paralleled the effect of those manipulations on polar-angle gain. That is, the lower the fidelity of the EP representation of the DTFs, the lower the observed polar-angle gain. For the contrast reduction manipulation, as spectral compression increased, EP RMS distortion (panel g) steadily increased and EP contrast (panel i) steadily decreased, which did not match the sudden drop in polar-angle gain observed behaviourally only at the 25-% contrast factor. The EP correlation metric best conformed to this pattern for the contrast reduction condition, although the reduction in correlation (from 1 to 0.95) was rather modest. For the contrast expansion condition, neither the dramatic increase in EP RMS distortion nor EP contrast with increasing contrast factor matched the behavioural results, which exhibited statistically significant but modest increases in normalized gain at 150 and 200 %. The smallest value of EP correlation of 0.9 for the 400-% contrast factor was not matched by low polar-angle gain in that condition, which was not statistically different from 1.

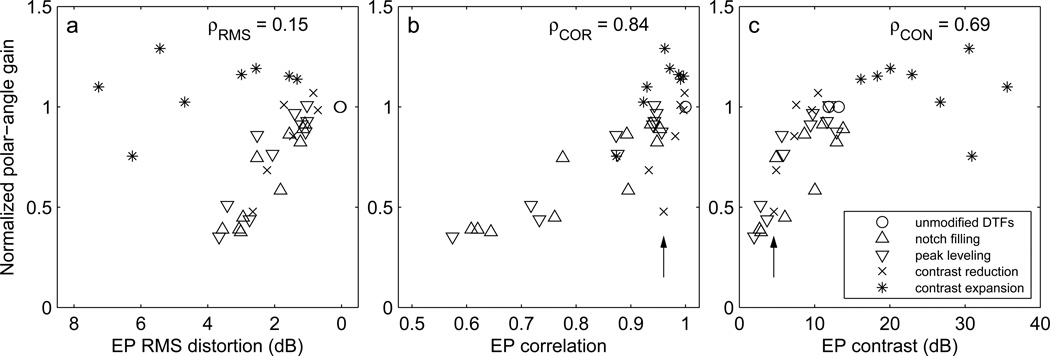

To better illustrate how well each of these metrics could predict the resulting behavioural polar-angle gains, in Fig. 11 the front- and rear-hemisphere gain values values from Fig. 7 were plotted against the values for each metric from Fig 11. Correlation coefficients between the observed gain and computed EP values were computed for each metric (ρRMS, ρCOR, and ρCON). These plots suggest that if the contrast expansion condition (* symbols) were excluded, all three metrics would have been similarly successful in predicting the gains for the notch-filling, peak-levelling, and contrast reduction conditions. The correlation values for ρRMS, ρCOR, and ρCON with contrast expansion data excluded were similar and equal to 0.89, 0.87, and 0.81, respectively. Including data for all four manipulations, the EP correlation proved to be the best predictor of performance (ρCOR = 0.84), while the correlation for EP contrast was substantially lower (ρCON = 0.69; polar-angle gain did not continue to increase for EP contrast > 15 dB), and that for the EP RMS distortion was very small (ρRMS = 0.19; polar-angle gains near 1 were observed despite large RMS distortions for the contrast expansion condition). The symbol (×) indicated by an arrow in Fig. 11 panels b and c corresponds to the front DTFs with a contrast factor of 25%. Low polar-angle gain was observed in this condition despite the high EP correlation, perhaps due the very low EP contrast.

Figure 11.

Mean polar-angle gain as a function of excitation pattern quality metrics. a) EP RMS distortion; b) EP correlation; c) EP contrast. Symbol-shape indicates the type of DTF manipulation applied. Front- and rear-hemisphere cases are plotted separately but with the same symbols. ρRMS, ρCOR, and ρCON indicate the correlations between the gain and metric values. The vertical arrow indicates a case (×, discussed in the text) for which EP correlation was high while gain and EP contrast were low.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1. Spectral contributions to the level and negative level effects

In Experiment I, we used DTF spectral notch filling to model the assumed distortion of the DTF spectral representation at near-threshold intensities. Notch filling resulted in a graded decline in polar angle gain as the notch-filling floor was raised from −5 to +15dB. This result was very similar to the changes in gain observed as stimulus intensity was reduced for noise bursts at sensation levels below 20–30 dB (Sabin et al., 2005). Comparison of the data in Fig. 1a and Fig. 7a for front-hemisphere targets, shows that both the dB range (of sensation level or notch-filling floor) over which this gain reduction was observed and the absolute change in gain were similar for the low-intensity and notch-filled stimuli. This suggests that notch-filling was a good model for the distortions in peripheral representation of spectral cues at near-threshold intensities, and supports the hypothesis that such spectral distortions (and not simply low-intensity presentation per se) are major contributors to the Level Effect. Our results, however, differ from those seen at near-threshold intensities in free-field in that only one of our five listeners exhibited the increase in vertical-plane response variability consistently observed under those conditions (Fig. 1c). Thus, an increase in variability does seem typically to require true low-intensity presentation.

In Experiments I and II, we used both peak-levelling and spectral contrast compression as simple models of the saturation or compression of the DTF spectral representation at high intensities. Vertical-plane localization performance was also adversely affected by both manipulations, which is consistent with the hypothesis that spectral distortions also contribute to the negative level effect. Although a simple relation between notch-filling floor limit and stimulus sensation level seems to exist, it is more difficult to equate the amount of saturation or compression that might occur at high stimulus levels with the peak-levelling and spectral contrast compression manipulations used here.

Since only the most extreme filling or levelling manipulations resulted in precipitous declines in performance, spectral-cue processing seems to be fairly robust to moderate changes in the shapes and amplitudes of DTF peaks and notches. The system also seems quite robust when, by means of spectral contrast compression, the amplitudes of these features are altered without distortion of their shapes. This latter finding suggests that some reduction of spectral contrast by means of multi-channel wide dynamic range compression in devices such as hearing aids need not by itself have severe adverse effects on listeners’ use of spectral cues provided that the shape of the DTF is substantially preserved. Of course, numerous other factors related to sensorineural hearing loss such as non-linear growth of loudness, broadened auditory filters, and increased high-frequency thresholds would be expected to impair access and sensitivity to spectral localization cues.

4.2. Relation to level-dependent quality of spectral encoding in the auditory system

A physiological correlate of the negative level effect exists in the finding that the encoding of spectral profiles in the pattern of discharge rates across the auditory nerve tends to degrade due to saturation of firing rates at high stimulus intensities. This has been observed for vowels (Sachs and Young, 1979) and for DTF-filtered noise bursts (e.g. Reiss et al., 2011). Consistent with this, Alves-Pinto and Lopez-Poveda (2005) have reported that listeners’ ability to detect notches in wideband noise spectra declines with increasing stimulus intensity.

Reiss et al. (2011) have, however, identified a population of low-spontaneous-rate (LSR), high-threshold fibers in the cat which have extremely large dynamic ranges, and for which spectral encoding remains robust at higher intensities. They propose that since cats’ vertical-plane localization performance does not decline at high intensities (for relatively long noise-burst stimuli), these fibers are the ones subserving vertical-plane localization. The same study showed that the population of high-spontaneous-rate (HSR), low-threshold fibers did maintain high-quality spectral encoding at near-threshold intensities, whereas “decreased sensitivity constrained the ability of LSR fibers to encode HRTF features at low sound levels.” If vertical-plane localization also relied on the HSR fibers, the near-threshold level effect should not be as pronounced as is observed. Thus, reliance on the high-threshold, LSR fibers is consistent with the level effect, if not with the negative level effect. Gai et al. (2013) have demonstrated that awake behaving cats do exhibit level and negative level effects similar to humans’.

The effect on auditory nerve spectral encoding of reducing the stimulus duration to the range exhibiting the strongest negative level effect (<10–20 ms) has not been measured in vivo, but has been investigated by Gai et al. (2013) using a detailed computational model of the behavior of medium-spontaneous-rate fibers. They found that the coding fidelity of DTF spectral profiles was significantly reduced at low and high levels regardless of stimulus duration, and from that observation concluded that the recovery from the negative level effect at long durations could not be explained in the auditory periphery.

4.3. Effect of low intensity and spectral distortion on lateral angle gain

An explanation for the increased lateral angle gain observed in the most extreme spectral-manipulation conditions of this study and in the near-threshold intensity conditions of Sabin et al. (2005) and Vliegen and Van Opstal (2004) is not obvious. In those latter experiments, involving true low-level presentation, one might expect some degradation in the quality of the peripheral representation of the binaural cues, but that should not be the case for the supra-threshold levels used in the present study. The increase in lateral angle gain in our spectral distortion conditions cannot be attributed to changes in interaural time or level difference cues caused by the manipulations since we were careful to preserve natural binaural cues in all our stimuli. We think it unlikely that spectral degradation directly and systematically affected perceived lateral angle because listeners do not weight spectral cues heavily in forming lateral angle judgments (Macpherson and Middlebrooks, 2002).

The low-level “bump” in lateral angle gain observed in Sabin et al. (2005) was accompanied by an increase in response scatter (Fig 1c), perhaps indicating increasing listener uncertainty, but this was not the case in either Experiment I or II of the present study. Instead we observed an increase in lateral angle gain with extreme notch filling, peak levelling, or spectral contrast reduction, but no associated increase in lateral angle scatter. If a common mechanism does explain the increase in gain observed in these studies, it might be a listener-specific response strategy in the face of any stimulus with degraded spatial cues. As seen in Fig. 1d, only three of six listeners in Vliegen and Van Opstal (2004) exhibited the low-intensity lateral-gain boost, and the large lateral-angle gain error bars in Fig. 1c are due to large differences between individuals in Sabin et al. (2005).

4.4. Differential influence of peaks and notches

The results of Experiment I have the potential to provide information about the relative importance of notch and peak features in vertical-plane sound localization because the manipulations used altered the shapes and amplitudes of DTF spectral notches and peaks independently. Various lines of research described in the literature have emphasized the importance of either notches (e.g. Bloom, 1977; Rice et al., 1992) or of peaks (e.g. Blauert, 1969/70; Butler, 1997). Psychophysical and physiological evidence suggests that peaks and notches are represented at least somewhat independently in the auditory system. For example, frequency-modulated peaks and notches can produce independent spectral motion after-effects (Shu et al., 1993), detection and discrimination of high-frequency notches are somewhat worse than for peaks (Moore et al., 1989), and a population of principal cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the cat has been shown to specifically enhance the representation of spectral notches (Young et al., 1992; Imig et al., 2000; Young and Davis, 2002).

In Experiment I, mild notch filling reduced polar-angle gain more rapidly than mild peak levelling, but the overall patterns of gain as a function of filling or levelling floor and ceiling limits were qualitatively similar (Fig. 7 a and d), and there were no statistically significant differences between the rates of large polar-angle errors (which are predominantly front/rear reversals) caused by notch filling and peak levelling. This study therefore does not provide strong evidence in favor of the dominance of either spectral feature; sound localization appears to be somewhat robust to mild degradation of either peaks or notches, but sensitive to larger modifications of either type of feature. Our result is contrary to the findings of Zhang and Hartmann (2010), who performed DTF notch filling and peak levelling at a single common floor and ceiling value and found notch filling to be more detrimental to accurate front/rear localization, but it is consistent with studies using artificial DTFs with reduced numbers of spectral features that have concluded that a mixture of peaks and notches is necessary for accurate vertical-plane localization (e.g. Langendijk, 2002; Iida et al., 2007).

4.5. Implications for models of spectral cue processing

The degree to which relatively accurate vertical-plane localization persists under conditions of substantial notch-filling, peak-levelling, or spectral contrast alteration provides evidence about the manner in which the auditory system extracts information from DTF spectra. Accounts of spectral cue processing can be considered to differ in two independent factors: in how they propose that the spectra are represented centrally, and in how those representations are subsequently mapped to spatial percepts. The spectral representation might be based on the complete spectral profile or alternatively on a sparse representation containing only the frequency loci of discrete spectral features (Macpherson, 1997, 1998; Langendijk, 2002; Iida et al., 2007). One class of models of spectral-cue processing proposes that mapping takes place when the observed spectrum is compared with a learned or hardwired bank of spectral templates, and that the apparent location of a source is determined by the location corresponding to the best-matching template (e.g Zakarauskas and Cynader, 1993; Middlebrooks, 1992; Langendijk and Bronkhorst, 2002). We have described that type of mapping model as associative (Macpherson, 1998). Another class of mapping models, that we have termed morphological, proposes that some dimension of location can be computed directly from a simple or complex feature in the shape of a single DTF without comparison with any others. Examples of this second class are models in which source elevation is held to be signalled by particular differences in the spectral energy falling in specific “directional” frequency bands (e.g. Blauert, 1969/70; Butler, 1997) or by the frequency of the primary high-frequency DTF notch.