Abstract

Background

If mentally ill individuals become violent, mothers are most often victims, yet there is little available research addressing how, when, and from whom mothers seek help for themselves and/or their children when they become victims of this form of familial violence.

Objectives

The purpose of this research was to describe how mothers understood violence their mentally ill, adult children exhibited towards them and to articulate the process mothers used to get assistance and access mental health treatment when this violence occurred.

Method

Grounded Theory methods were used to explore and analyze mothers’ experiences of violence perpetrated by their mentally ill, adult children. Eight mothers of violent, adult children with a diagnosed DSM Axis I disorder participated in one to two open-ended interviews. Mothers were of diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Results

Getting immediate assistance involved a period of living on high alert, during which mothers waited in frustration for their children to meet criteria for involuntary hospitalization. This was a chaotic and fearful period. Fear and uncertainty eventually outweighed mothers’ abilities to manage their children’s behavior, at which time they called the police or psychiatric evaluation teams, who served as gatekeepers to mental health treatment. Mothers accepted the consequences of being responsible for their children’s involuntary hospitalization or of being left home with their children if the gatekeepers did not initiate involuntary hospitalization.

Discussion

Mothers can identify signs of decompensation in their ill children and recognize their need for hospitalization. They cannot, however, always access mental health treatment due to their children’s refusal and/or failure to meet legal criteria for involuntary hospitalization. Mothers’ inability to intervene early sometimes results in their own violent victimization.

Keywords: family violence, mental illness, mental health services, access to health care

Although no more prone to violence than the general population, research has shown that when individuals who are mentally ill become violent, family members are most often the victims (Arboleda-Florez, 1998; Steadman et al., 1998; Tardiff, 1984). Parents are the most common victims (Binder & McNeil, 1986; Straznickas, McNeil & Binder, 1993), specifically mothers (Estroff, Zimmer, Lachicotte & Benoit, 1994; Estroff, Swanson, Lachicotte, Swartz & Bolduc 1998; Estroff & Zimmer, 1994). However, little is known about the experiences these family members have attempting to get help for their violent, mentally ill children. This research describes the experiences of mothers who have been victims of violence perpetrated by their mentally ill, adult children, including the process they go through to get assistance. This study addresses the gap in the literature with respect to mothers’ perceptions of access to mental health treatment, in the form of hospitalization, and interactions with police and mobile psychiatric evaluation (PET) teams when their mentally ill children become violent towards them.

Background Literature

Family members play a very important role in accessing mental health treatment for their relatives, often assuming responsibility for getting them to the hospital. Additionally, family members are as good as, if not better, than PET teams and/or police in determining whether or not their relatives need hospitalization. In one study of 311 psychiatric emergency room referrals, 43% of patients evaluated were brought in by relatives while 36% came in with police (Dhossche & Ghani, 1998). Strauss and colleagues (2005) found that individuals brought to the hospital on mental inquest warrants initiated by family members were significantly more likely to be hospitalized than individuals brought to the emergency room by a mobile crisis team. However, mobile crisis teams and police officers remain gatekeepers to treatment for many individuals. Mobile crisis teams and police officers are often the first to respond to mental health related emergency calls in the community. When responding, the determination of whether or not to initiate hospitalization is often at their discretion, regardless of the family’s sense of what is best (Lamb, Weinberger & DeCuir, 2002; Teplin, 2000).

This initiation of involuntary hospitalization is often a first step in procuring mental health treatment of any kind. Since family members cannot initiate this process, even when they believe it is in their relatives’ best interest, they rely on the police and PET teams. In their role as gatekeepers to mental health treatment however, it has been reported that the police often prefer to respond to individuals who are mentally ill informally rather than arrest or involuntarily hospitalize them (Lamb, Weinberger & DeCuir, 2002; Teplin, 2000). This could be, in part, due to a lack of cooperation between mental health systems and police. In a study of police perspectives on responding to mentally ill individuals in crisis, less than half of the officers reported that their mental health systems or emergency rooms were moderately or very helpful (Borum, Deane, Steadman & Morrissey, 1998). The lack of cooperation from emergency room staff may be a result of unavailability of resources to manage psychiatric patients. In a survey of 223 California emergency departments, 50% reported that no mental health professional was available for evaluation of suicidal patients (Baraff, Janowicz & Asarnow, 2006). Whether due to lack of collaboration or lack of resources, gatekeepers not initiating hospitalization may prevent individuals in need of mental health treatment from receiving it. Some mentally ill individuals may not recognize their need for treatment and family members are not able to access treatment on their relatives’ behalf. Consequently, gatekeepers’ willingness and ability to access the mental health system are often key components in treatment acquisition.

Family members also report dissatisfaction with their inability to access mental health treatment during periods of their relatives’ decompensation (Winefield & Harvey, 1994). Most civil commitment laws only allow involuntary hospitalization when a person is imminently dangerous or gravely disabled. Some states, however, permit involuntary hospitalization if an individual may deteriorate to the point where they become dangerous or gravely disabled (Petrila & Levin, 2004). Therefore, in situations where laws prohibit commitment until an individual is actually dangerous or gravely disabled, family members must attempt to manage their relatives’ behavior while also watching their mental health deteriorate.

Methods

Design

Grounded theory methodology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used to guide this study, leading to the development of a theoretical map of the process mothers use to get immediate assistance when their mentally ill adult children become violent. Symbolic interactionism provided a theoretical foundation for this research. This sociological theory proposes that meaning is derived through social interaction and through the person’s interpretation of those interactions (Blumer, 1969). It was therefore assumed that mothers interpret their children’s mental illness and violent behavior in a way that makes sense to them in the context of their daily lives and that the meaning of both affects their responses to the violence they experience.

After institutional review board approval, social workers and charge nurses at two adult locked inpatient psychiatric units in a large urban area were trained and assumed responsibility for recruitment of mothers. These health care professionals invited patients’ mothers, with whom they already had contact due to their clinical responsibilities, to participate. The investigators had no access to any clinical patient information at any point during the research and no access to any identifying information of women who were invited but did not participate in the study. Participants were also recruited at a National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter by the primary investigator who introduced the study at an open meeting. All interested mothers were responsible for initiating contact with the primary researcher. Only after interested women contacted the primary investigator were they screened for eligibility. Eligibility requirements included being a mother under age 65 with a child (biological, step, or adopted) age 17 or older, with a DSM – IV Axis I psychotic, mood or anxiety disorder in the absence of a co-occurring substance abuse or personality disorder, exhibiting violent and/or threatening behavior towards the mother.

Data were collected via open-ended interviews. An interview guide was developed to elicit the mother’s experience of getting immediate assistance for themselves and/or their children when their children became violent. Special probes were used to explore the mothers’ experiences of violence perpetrated by their children, and their decision-making process used to seek immediate assistance when their children became violent. Every woman was asked, “Can you tell me about a time when your son/daughter has been violent in your family?” Additional interview probes are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Additional Interview Probes

|

| If the scenario described did not involve the woman interviewed as a victim of the violent behavior she was asked to describe a time when she was the victim and followed with similar prompts. |

Sample

Fourteen interested women contacted the primary investigator; six were not eligible, therefore, the sample consisted of eight women. All were interviewed by the primary investigator one or two times in their homes or in another safe and private location of their choice such as a park or place of worship.

Of the eight participants, two self-identified as white, two as African American, one as African, and three as Latina or Hispanic. Five women were married, one was single, one was divorced and one widowed. The children whom the mothers identified as violent and mentally ill were all single adults, and three were residing with their mothers (the participants). All of the children were biological children except one who was a nephew adopted as a son. Five women were mothers of sons, two women had daughters, and one woman had both a son and daughter who were mentally ill and violent. Per the mothers’ reports, all of the nine children were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder (4 schizophrenia, 3 schizoaffective, 1 bipolar/schizophrenia, and 1 psychotic disorder not otherwise specified/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). Only half of the women felt that their household income was adequate to meet their needs. The ages, education attained, employment and insurance status of the mothers and the children they identified as mentally ill and violent are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Sample (Mothers) and Children They Identified as Violent and Mentally Ill

| Mothers (n = 8) | Children (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age Range | 42 – 60 | 20 – 38 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| Less than HS | 2 | 3 |

| Graduated HS | 3 | 5 |

| Some College | 3 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Employed | ||

| Part Time | 2 | 0 |

| Full Time | 3 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Uninsured | 4 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Reported Monthly Income | 1 - Unreported | |

| Under $1000 | 2 | |

| $1100 – $2000 | 1 | |

| $2100 – $3000 | 0 | |

| $3100 – $4000 | 1 | |

| $4100 – $5000 | 3 | |

|

| ||

| Number of People Supported by Monthly Income | ||

| 1 | 3 | |

| 2 | 1 | |

| 3 | 3 | |

| 4 | 1 | |

Data Collection, Analysis and Interpretation

After obtaining written informed consent, interviews were audio-taped and lasted 1.5 – 2 hours. The women received $20 for their participation. The primary investigator conducted all interviews. Observational, theoretical, and methodological field notes were written immediately after each interview. These notes included events seen or heard during the interview, interpretations of the interview, early hunches, self reflection, and self critique of the interview (Schatzman & Strauss, 1973).

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Transcripts were coded line-by-line. During open coding each sentence was broken into as many codes as possible (Hutchinson & Wilson, 2001). Open codes were collapsed into categories and related to one another, moving data analysis to a higher level of abstraction. Properties and dimensions of categories were identified and linked with relational statements (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In an effort to identify and articulate variations in emerging categories and theoretical relationships, as theoretical development occurred, both researchers independently engaged in comparative analysis of existing and incoming interview data. Following this independent analysis, each interview was then discussed and analyzed collaboratively to ensure rigor. The theory presented is consequently the result of an analytic process in which both investigators independently and then collaboratively engaged in coding, abstracting, and articulating theoretical concepts and relationships. Note taking and memo writing throughout data collection and analysis generated an audit trail.

Results

Violent Behavior as a Key to Mental Health Treatment

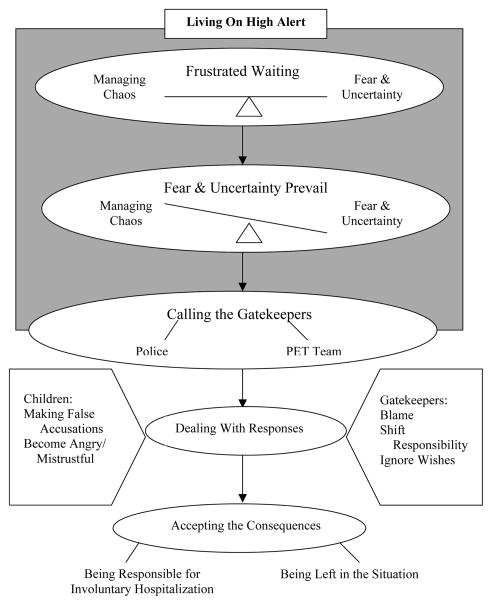

The women all had extensive experience attempting to get their children mental health care and understood violent behavior as crucial for accessing mental health treatment. They understood that because their children were adults they could not be hospitalized involuntarily unless they met certain criteria. While their children were decompensating, experiencing worsening symptoms, and exhibiting disruptive behaviors, the mothers knew that hospitalization would not occur unless their children’s behavior escalated to the point of being dangerous towards themselves or somebody else, perhaps them. Once their children became violent, they knew that they could get their children assistance through involuntary hospitalization. The entire process from the beginning of decompensation to the calling of the PET team is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mothers’ process of getting assistance when their mentally ill, adult children become violent towards them.

Getting Immediate Assistance: Living on High Alert

For the mothers, the process of getting assistance initially involved a period of hypervigilance in which they felt as if they were on “high alert all the time.” This was an intense period of watching what was happening and coping with the problems their children were creating. During this time, the children’s lives seemed less and less in order. Mothers characterized their children as going into “spirals” and getting “out of whack and out of control.

As one mother stated,

Your life is intense. You walk around on egg shells. Your life is not happy, especially when they get really, really ill…, sometimes my whole family has this intensity of drama and anxiety…. There was a time where she was just constantly bathing every 5 minutes, every 5 minutes. She would overflow my house and water would go through the living room, through the kitchen. Pots were being burned, the carpet almost catching on fire. And then when she wakes people up at night cussing and yelling and screaming and… she leaves nobody going to sleep.

During this period, mothers worked hard to maintain some balance despite their sense of things getting out of control. Through it all, they remained vigilant, “on high alert,” amidst the building sense of impending danger. But through this period, there was little they could do if their child did not want help. Watching their child in this phase was characterized by excruciating emotions and a pervading sense of powerlessness.

Frustrated Waiting

While their children decompensated right before their eyes, mothers waited for the inevitable point at which their children would meet criteria to be hospitalized involuntarily. Their living environments were filled with stress and growing tension. The mothers knew that their children needed help, but they had no other option but to wait until something dangerous, even life threatening, happened. As one woman said of this period, “So what do I have to do? Do I have to sit here and wait and wait and wait and wait until that explosion happens?” Another said of her experiences, “It’s like you wait till something horrible happens before something can be done and that’s one of my frustrations… the longer it [mental illness] goes unchecked, the worse the state becomes.... I don’t know what he’ll do. And I don’t want the button pushed to that point because I don’t want him to hurt me.”

During this period of waiting until their children became overtly dangerous mothers were exposed to a barrage of additional troublesome behaviors from their children. One mother said of these other behaviors, “Most of the time it was screaming and throwing things, kicking the walls, breaking the doors, slamming the doors and throwing anything that’s on the shelf off the shelves. Then it got to the point where it was starting to get physical.” Nonetheless, mothers were forced to manage these behaviors because they were unable to attempt to hospitalize their children against their will.

Fear and Uncertainty

As this stage while decompensation continued, most of the children were not taking any medication. The longer they went without medication and/or other treatment, the more unpredictable their behavior became. The mothers were both afraid of their children and they were uncertain of what was going to happen next. One woman said of her son,

In my spirit I felt like, geez this boy may pull a knife or something and really he won’t have that intention of doing it…. One time we were in the living room and he came and I could see his fists. He said, ‘sometimes I just want to kill you.’…I don’t know when that’s a breaking point…. I know it keeps escalating if he doesn’t get help or medication. And that’s my point, I don’t know how far it will escalate… but there are times when I know that it’s an unsafe time for him and for me.

The mothers’ fear grew while their sense of uncertainty continued to escalate. The women truly didn’t know what their children might do; anything could happen. The sense of simultaneously knowing their children so well, but not knowing the dangerous extent to which their behavior might lead, only added to the emotional conflict and tension. Danger seemed inevitable and they were acutely alert to this impending reality. Mothers knew that a violent outburst was looming, yet they were disconcertingly uncertain of how, when or under what circumstances it would manifest.

Managing the Chaos

While they awaited their children’s violent outburst, mothers used a variety of techniques of “dealing with,” “struggling with,” and “handling” the unpredictability of their chaotic environment. One mother coped by finding “things to occupy his time” (her son’s). Other women distracted their children with music and activities. Some mothers avoided their children by isolating themselves. One mother described herself as “a prisoner up in my room.” Mothers also reoriented their children to the present and set limits on their children’s behavior by telling them not to engage in certain behaviors. One mother told her son “you need to stop and think, that’s not real, stop it” or “you need to back up…you need to go and sit down and just be still” when he would make delusional comments or “get in [her] face.”

Despite the potential volatility of the situation, this period could go on for days. For many mothers, this was a period of round-the-clock, steadfast caregiving and focus on their children despite the chaos. One mother discussed her situation as always checking and watching, “She’s just done a lot of things, just yelling and screaming in the middle of the nighttime… You’re just like ‘Stop it, it’s too much….’ You have to walk into her room to see that she’s not catching the house on fire and you have to wake up constantly to see ok is she awake, asleep or not.”

Other family members (husbands and sons) were often involved in attempts to manage and control the environment during this period in order to maintain everyone’s safety. One woman described her husband as “the person who comes down and stops everything and even then he can’t really control her anymore like he used to.” For several families, in order to “control” their children, it was necessary to physically restrain them to prevent them from “really hurting themselves or someone else.”

Despite the mothers’ use of distraction, limit setting, and vigilance as their children grew more unpredictable, mothers ultimately became increasingly less confident in their own efforts to manage their children’s behavior. Would they be able to handle the next outburst? Eventually, fear and uncertainty clearly outweighed mothers’ perceived ability to manage, control, and quell the chaos their children were creating.

Tipping the Balance: Fear and Uncertainty Prevail

The transition from the period of frustrated waiting to the point at which fear and uncertainty overwhelmed the situation came when the mothers ran out of ways to control their children’s behavior and lost confidence in their ability to cope. Once their fear or their uncertainty outweighed their perceived ability to manage their children, the mothers determined that the situation was just too unsafe to manage without assistance. This was the tipping point and the women could not wait any longer; they needed help. Intervention simply must be accessed because they were now desperately afraid for their own safety because their children’s condition continued to worsen without treatment.

One woman noted she would wait until her child “actually hit” her, or until she sensed it was leading to violence. Another said she, “didn’t call the police in the beginning because we were able to settle her down, but then the attacks got more violent.” Other women reported feeling too threatened and overwhelmed to manage their children. Despite variable tolerance levels for threats to their safety, each woman finally came a point when she felt that she could no longer help her child. The techniques used to manage their children (distraction, reorientation, isolation) became ineffective or too tiresome to continue. The family’s response was an additional important indicator of the level of danger. One woman noted that the situation “gets too hard, too much to handle…when finally the family gets worried and too tired.” This helped the women know their efforts were no longer effective in “settling down” their children. It was at this point that they called for assistance.

The “point” at which the police or PET team was called was described by all mothers as when they “didn’t know what to do.” One reported, “I’m the mom, I’m not the doctor, but I just knew something was terribly wrong. And I knew why, but I didn’t know what to do about it. So I did my best and… I had to call the PET team because I was actually scared of him.” Another said of her son, “He was just so unmanageable and boisterous…. So it got, at one point, I had to put him, I had to call the PET team and they came and got him because I just, I didn’t know what to do with him.”

Calling the Gatekeepers

Finally, the mothers were at the point at which they called the police or PET team evaluators for assistance. For mothers who were unable to get their children into the hospital themselves, the police and PET teams were gatekeepers to mental health treatment. Once their children actually became violent, mothers knew their children could enter the mental health system and be treated involuntarily. When the police or PET team evaluators arrived, they not only decided whether or not to remove the child from the home, but they were also responsible for deciding if the child should be taken to a hospital or to jail. For some women calling these gatekeepers was as easy as asking them “to take [their child] away.” Others described the police as “not a help at all.” It was not perceived as helpful when the police advised mothers to get restraining orders against their children, because most mothers did not want to do this. Also, mothers indicated that they felt the police behaved unprofessionally. One mother said of an encounter with the police,

I didn’t like their attitude this time when they came. The guy tried to be really funny like said ‘well who am I gonna pick up? Who’s the one, who am I taking to jail?’ And I even turned around and told him ‘look this is a mental patient. She’s my daughter and is very ill.’ But the sarcasm that they walked into the house with I didn’t particularly care for.

In most instances it was clear to the police that the child was mentally ill. During some altercations, however, another woman’s daughter would call the police before her mother was able to. She described situations in which her husband was nearly arrested.

It got to the point where she would kick, sock, dig her nails into me, pinch, but really hard so you have to defend yourself so I always thought “I’m gonna sock her really hard and get her off of me.” And I did that a couple times and she called the police on me. And the police come and then you have to explain what’s going on…I don’t know how many times they almost arrested my husband because, you could see him fuming because he’s like mad because he’s desperate. Desperate for the situation and desperate because nobody’s listening. She would use that. She would call the police and say ‘they’re hitting me’ or ‘my father is dragging me across the floor.’

For all of the women, calling the police or PET team was not an immediate reaction to the first signs of their children’s decompensation. In many instances the situation had escalated to the point where the mothers needed to defend themselves from their children.

Dealing With Responses From Both Sides

In addition to feeling “desperate” because they were not listened to, when mothers called the police or PET teams they dealt with responses, typically negative, from these gatekeepers as well as from their children.

Responses From the Gatekeepers

Blaming the mothers

The women cited blame as a common reaction of the police. The police often blamed mothers for allowing their children to be in the home. Women sometimes felt as though the police were interrogating them. One mother said,

It got to the point where the police were down here three or four times a week. And I think they were getting a little mad, and they would ask, ‘why do you let her come back?’ ‘She’s my daughter. She’s sick. She has nowhere to go, what do you think?’ ‘Well you need to evict her.’

Often, the police insinuated that if the women did not allow their children in their homes, violence would not occur and the mothers would not need to call for assistance. They inferred that the mothers were responsible for their own victimization and resulting need for assistance.

Ignoring the Wishes of the Family

Mothers sometimes felt they needed to talk the police into taking their children to a hospital. The police “just try to settle it down and then they would leave” despite the mothers’ requests to have their children hospitalized. Even when mothers were assaulted and requested to press charges, the police were hesitant to take the children to jail. One woman described her experience trying to press charges against her daughter,

So it has escalated to violence, to the point where I say, ‘yeah go ahead and charge her with assault.’ It’s really hard to talk the police into that. So finally they did take a report because she came running up to me with a knife outside and she stabbed my tires and I took off and I called the police. Out of the maybe 25 times that’s the only time they took a report. Because I insisted.

The women frequently felt as though the police simply did not want to take the time or energy to help them. When the police refused to press charges, mothers thought it was because the police would rather take their children to a hospital and let the situation be handled via the mental health system, rather than bother with formal legal charges. Either way, the women often described having to “beg” the police to hospitalize their children or press charges.

Shifting Responsibility

The police attempted to shift responsibility for intervention onto the mothers. Sometimes the mothers were told that the PET evaluators were out on other calls and would need to get their children to a hospital on their own. When the police did come to one woman’s home she felt the police,

…didn’t want to take the time to take her [to the hospital] for me and I kept on saying ‘she’s giving me a hard time.’ And they said ‘well you take her to the hospital.’ I understand they could if they want to take her. They were not doing anything at that time and they said ‘oh no, no…well we’ll get her in your car for you’ and I said ‘but she’ll just jump out.’ They said, ‘we don’t want to take her, you take her.’

This woman did attempt to take her daughter to the hospital and as she predicted, her daughter jumped out of the car on the way. Several women said the police told them it was “difficult” to take their children either to the hospital or to jail. One mother reported that the police “would tell me, ‘well it’s really hard because [we] take her down to the hospitals and the nurses, all they do is yell at [us] because they don’t want to take them [patients]’.”

Responses From the Children

Making False Accusations

Mothers called the police or PET team in what they thought was their children’s best interests. Their children, however, frequently reacted by making false accusations about their mothers. They accused their mothers of stealing money, using drugs, molesting, and beating them. One woman said,

the police will come in here and she’ll tell the police when they’re taking her, ‘my mother’s a drug addict, she’s a drug addict, she’s using my money, she’s robbing my money and she’s buying drugs with it’…. And the police would… give me a look like, ‘hmmm I wonder about that lady.’ And I felt very uncomfortable.

When children made such accusations, mothers wondered if the police believed them.

Becoming Angry

As illustrated above, the false accusations made against the mothers are often a result of their children’s anger. One woman said of her daughter’s hospitalization, “she only came back out more defiant with me, not understanding. Mad at me because you know ‘you put me into the hospital’ like she never forgave me for that. Well she still doesn’t.”

Mothers Accept the Consequences

Being Responsible for Involuntary Hospitalization

Calling the police or PET team conjured up mixed emotions. The mothers felt sorry that they were responsible for hospitalizing their children against their will. One woman said, “I don’t want to see the police take my son out of the house. I feel terrible.” On the other hand, another woman said, “Naturally I didn’t want him in the hospital if he could live here, but actually when he was in the hospital was the only time I could breathe. That I felt like he was safe cause he was locked up.” The mothers felt both sad and relieved for being responsible for having their children hospitalized involuntarily.

Being Left in the Situation

Sometimes the police or PET team evaluators chose not to involuntarily hospitalize the children. On one occasion a woman said she called “the Sheriff’s department and asked them to take him [her son] away and so they took him around the corner and let him out.” Another woman said the police “come and talk to him, and they leave.” In these cases the police simply tried to handle the situation themselves. Despite one mother’s wishes to hospitalize her daughter, the police “would always just try to settle it down and then they would leave, and I would tell them, ‘she needs to be taken,’ and they wouldn’t take her.”

In situations such as these, the women were left in the same situation they were in prior to calling for assistance. Once the police were gone, mothers were required to once again attempt to manage their children’s behavior on their own. The children continued to create chaos in their homes. All of the mothers whose children were left in the home eventually needed to call for assistance once more after becoming overwhelmed or afraid.

Discussion

The mothers in this sample were very experienced at dealing with the behavior of their mentally ill children. They understood the violence their children exhibited as a manifestation of their deteriorating mental health. The mothers could, with 100% accuracy, predict episodes of violent behavior which occurred in the context of their children’s decompensation. Despite knowing that they could ultimately be the victims of their children’s violent behavior in the absence of mental health treatment, they had no choice but to watch helplessly as their children’s mental health deteriorated and await their own violent victimization. They could not force their children into treatment against their will. Had these mothers been able to obtain involuntary treatment for their children earlier, it is possible that they would not have been victims of violence and their children would not have experienced as dramatic a decompensation.

Longer periods of untreated psychotic episodes have been associated with poor treatment outcomes (McGlashan, 1999; Keshavan et al., 2003). Mothers in this sample wanted their children to have access to mental health treatment earlier. They could not, however, initiate involuntary treatment. The primary goal of involuntary hospitalization laws is to ensure that no individual is committed without evidence that s/he suffers from a mental illness and consequently is dangerous or gravely disabled (McCullough & Reinert, 2002). The reverse, however, ensuring that individuals suffering from a mental illness who are dangerous or gravely disabled are hospitalized and treated, is equally important and has little support. The mothers felt that their desire for early intervention was in their children’s best interests. Also, they did not want to be violently victimized. These mothers repeatedly voiced their frustration at having to wait until violence actually occurred before being able to access mental health treatment for their children. This situation resulted in worse outcomes for both mothers and their children.

One strategy that may have helped the mothers obtain involuntary treatment for their children and avoid violent victimization is outpatient civil commitment. Under the auspices of outpatient civil commitment, individuals who are living in the community can be involuntarily hospitalized when they become treatment noncompliant or begin to experience an escalation in their symptomatic behavior prior to actually becoming violent (Hyde, 1997). Several of the mothers tried to become their children’s conservator with legal authority to hospitalize their children, but could not do so because their children’s doctors did not believe they needed it. It is possible that these same doctors would not see the need to initiate outpatient civil commitment proceedings either. Given the degree of decompensation described and the violence exhibited, however, it seems likely that both the children and their mothers would have benefited from outpatient civil commitment.

Some of the mothers wanted to press charges against their children. Pressing charges was perceived as one avenue to get their children mental health treatment for three reasons. First, mothers believed that if their children were jailed for assault, the jail term would be longer than involuntarily hospitalization, and their children would receive mental health services while incarcerated. Second, they believed that if their children faced a judge, s/he would see that involuntary long-term care was indicated. Lastly, a record of violent behavior and legal involvement was desired by mothers seeking conservatorship as support for their request.

Given their inability to access treatment for their children, at a minimum caretaking mothers need supportive services to help manage their children and prevent their own violent victimization. Family psychoeducation has been shown to reduce relapse and the need for hospitalization in addition to improving the well-being of family members who participated (Dixon, et al., 2001). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team recommends that family members who have contact with a relative who is mentally ill be offered family psychosocial intervention addressing illness education, family support, crisis intervention, and skills training, lasting a minimum of nine months (Dixon, Goldman & Hirad, 1999). Despite its proven benefits, family psychoeducation is rarely offered (Dixon et al., 2001). Since the era of deinstitutionalization some family members have been forced to assume care of their mentally ill relatives, but state policies and funding to support their efforts have been extremely limited.

As a society we respect and value individual autonomy and the right to freedom. However, Wasow, a social worker and parent of a son with schizophrenia, suggests that family members “pay a heavy price for the freedom of their ill relatives” (1993, p. 208). If freedom from involuntary hospitalization is the ethical ideal our society is going to maintain, the ethical obligation to protect and support those family members held responsible for providing care to mentally ill individuals in lieu of hospitalization must also be considered. In order to protect both mentally ill individuals and their family members, such as those in this study, either hospitalization at the first sign of illness related decompensation or intensive supportive assistance for families is necessary.

Because there is no system wide emphasis on family oriented mental health services, mothers attempt to manage their children who are mentally ill on their own. Because there is no system wide emphasis on prevention of decompensation until something dangerous occurs, violent behavior is a key to mental health treatment and mothers know this. Caretaking mothers have been thrust into a position where they are expected to provide care to their children, without support and at times under the threat of impending physical harm. Without changes in the provision of services for mentally ill individuals and their family members it is possible that caretaking mothers will decide that they can no longer care for their children, potentially resulting in more mentally ill individuals being homeless and further taxing an already overburdened, underfunded community mental health system. In order for nurses to affect change in the provision of services to mentally ill individuals and their families, we must consider expanding our role of advocate to caretaking family members such as these mothers.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to thank dissertation committee members Drs. Nancy Anderson, MarySue Heilemann, and Sally Maliski from the UCLA School of Nursing and Dr. Doug Hollan from the UCLA Department of Anthropology for their assistance in conceptualizing and completing this research. Funding support for this dissertation research included a pre-doctoral fellowship through the National Institute of Nursing Research Grant 5 T32 NR 07077, Vulnerable Populations/Health Disparities Research at the UCLA School of Nursing and a Sigma Theta Tau, Gamma Tau Chapter research grant.

Contributor Information

Darcy Ann Copeland, Email: darcy.copeland@unco.edu, University of Northern Colorado, School of Nursing.

MarySue V. Heilemann, Email: mheilema@ucla.edu, University of California Los Angeles, School of Nursing.

References

- Arboleda-Florez J. Mental illness and violence: an epidemiological appraisal of the evidence. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;43:989–995. doi: 10.1177/070674379804301002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraff L, Janowicz N, Asarnow J. Survey of California emergency departments about practices for management of suicidal patients and resources available for their care. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;48(4):452–458.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder R, McNeil D. Victims and families of violent psychiatric patients. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 1986;14(2):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Borum R, Deane M, Steadman H, Morrissey J. Police perspectives on responding to mentally ill people in crisis: Perceptions of program effectiveness. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 1998;16:393–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0798(199823)16:4<393::aid-bsl317>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhossche D, Ghani S. Who brings patients to the psychiatric emergency room?: Psychosocial and psychiatric correlates. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Goldman H, Hirad A. State policy and funding of services to families of adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(4):551–553. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, McFarlane W, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Falloon I, Mueser K, Miklowitz D, Solomon P, Sondheimer D. Evidence-Based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(7):903–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff S, Swanson J, Lachicotte W, Swartz M, Bolduc M. Risk reconsidered: Targets of violence in the social networks of people with serious psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:S95–S101. doi: 10.1007/s001270050216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff S, Zimmer C, Lachicotte S, Benoit J. The influence of social networks and social support on violence by persons with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(7):669–79. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.7.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff S, Zimmer C. Social networks, social support, and violence among persons with severe, persistent mental illness. In: Monohan J, Steadman H, editors. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S, Wilson H. Grounded theory the method. In: Munhall P, editor. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective. 3. Boston: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde A. Coping with the threatening, intimidating, violent behaviors of people with psychiatric disabilities living at home: Guidelines for family caregivers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1997;21(2):144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan M, Haas G, Miewald J, Montrose D, Reddy R, Schooler N, Sweeney J. Prolonged untreated illness duration from prodromal onset predicts outcome in first episode psychoses. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29(4):757–769. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H, Weinberger L, Decuir W. The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(10):1266–1271. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough J, Reinert J. The necessity of individual rights and procedural justice in the civil commitment process: A response to the notion of “therapeutic justice”. The Vermont Bar Journal. 2002 Jun;:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan T. Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: Marker or determinant of course? Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:899–907. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrila J, Levin B. Mental disability law, policy, and service delivery. In: Levin B, Petrila J, Hennessy K, editors. Mental Health Services: A Public Health Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L, Strauss A. Field Research: Strategies for a Natural Sociology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Inc; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman H, Mulvey E, Monahan J, Robbins P, Applebaum P, Grisso T, Roth L, Silver E. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393–405. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss G, Glenn M, Reddi P, Afaq I, Podolskaya A, Rybakova T, Saeed O, Shah V, Singh B, Skinner A, El-Mallakh R. Psychiatric disposition of patients brought in by crisis intervention team police officers. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41(2):223–228. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-2658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straznickas K, McNeil D, Binder R. Violence toward family caregivers by mentally ill relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(4):385–387. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardiff K. Characteristics of assaultive patients in private hospitals. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141(10):1232–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.10.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin L. Keeping the peace: Police discretion and mentally ill persons. National Institute of Justice Journal. 2000 Jul;:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Winefield H, Harvey E. Needs of family caregivers in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1994;20(3):557–566. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasow M. The need for asylum revisited. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(3):207–208. 222. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.3.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]