Abstract

This study explored the relationship among Asian values, depressive symptoms, perceived peer substance use, coping strategies, and substance use among 167 Asian American college women. More than 66% of the women in our sample scored higher than the clinical cutoff score on the Center of Epidemiological Depression Scale. Three path analyses examining illicit drugs, alcohol use, and binge drinking indicated that perceived peer use was the most robust predictor of substance use. Depressive symptoms were positively associated with illicit drug use and alcohol consumption but were not related to binge drinking. Asian values and coping strategies were not predictive of substance use. Additional analysis revealed that avoidant coping was a strong predictor of depressive symptoms.

Keywords: alcohol use, Asian American Women, depressive symptoms, enculturation and coping strategies, peer use, substance use

INTRODUCTION

There is little theory or empirical investigation about the etiology of substance use and abuse among Asian American women (Iwamoto, Corbin, & Fromme, 2010) despite the fact that substance abuse, including alcohol use disorders, has significantly increased in this population (Grant et al., 2004). The model minority myth or stereotype of Asian Americans, and Asian American women in particular, may be a potential contributor of this lack of research focus. The model minority myth (i.e., that Asian Americans are academically and economically well-off) (Sue & Okazaki, 1990) assumes that Asian Americans experience protective factors associated with genetics or culture that contribute to high achievement and low incidence of mental health problems in comparison with Whites and other ethnic and racial groups (Yang, 2002). However, recent research suggests that the model minority myth is inaccurate (Wong & Halgin, 2006) and may contribute to an underestimation of substance abuse and mental health problems among Asian Americans (Mercado, 2000; Sue & Okazaki, 1990). The notion that Asian Americans do not experience substance use problems is in stark contrast to studies that indicate that Asian Americans experience mental health problems (Ja & Yuen, 1997; Liu, 2005; Liu & Chang, 2007) and substance abuse concerns (James, Kim, & Moore, 1997; Lee, Liu, & Eo, 2003; Nemoto et al., 1999; So & Wong, 2006). The few studies that have examined substance abuse and mental health problems among Asian American women have focused on Asian American adolescents. Subsequently, relatively little is known about the mental health and substance use and abuse of Asian American women. Although much of the extant substance use literature on college women focuses on White women, this study aims to contribute to the sparse body of literature on Asian American women and their substance use and mental health problems by elucidating the risk and protective factors of substance use and abuse among this population.

SUBSTANCE USE PROBLEMS AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS

Despite national efforts to reduce substance use among young adults between the ages of 18 and 24, binge drinking and marijuana and other illicit drug use has increased significantly among college students from 1993 to 1997 (Glendhill-Hoyt, Lee, Strote, & Weschler, 2000). Although marijuana use frequently begins in middle and secondary school, one-third of the 14,138 students in the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study began using substances in college and used marijuana more frequently during this period (Wechsler et al., 2002). In 2001, 44% of the college students sampled reported binge drinking (Wechsler et al., 2002), which paralleled the prevalence rates in similar studies conducted in 1997 and 1999 (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). Wechsler et al. (2002) also reported a sharp increase in frequent binge drinking among students attending all-women colleges. Frequent binge drinking is highly problematic because it is associated with an increased likelihood of using other substances, such as marijuana, cocaine, and other drugs (Vickers et al., 2004), as well as academic problems (Wechsler et al., 2000).

Although much of the extant substance use literature about college women focuses on White women, some research suggests that substance use among Asian Americans may be related to depressive symptoms (Otsuki, 2003), perceived peer use (Kim, Zane, & Hong, 2002; Liu & Iwamoto, 2007), cultural values (Yi & Daniel, 2001), and coping strategies (Franko et al., 2005). For this study, depressive symptoms, perceived peer use, and coping strategies were selected for investigation because these are areas where clinicians may target interventions to decrease substance use (Vickers el al., 2004). Cultural values were also important facets in this study because previous research suggests that understanding Asian American cultural values will likely inform future research and clinical practice (Liu & Iwamoto, 2006; Unger, Basezconde-Garbanati, Shaki, Palmer, & Mora, 2004).

DEPRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE

Depression is one of many factors that might contribute to the vulnerability of Asian American women to substance abuse. It has been well-established that depression and substance use often co-occur (Otsuki, 2003; Windle & Davies, 1999). Asian American women may be particularly vulnerable given that those between 15 and 25 have disproportionately high rates of depression and suicidal ideation (Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls, 1998). Psychological distress may exacerbate students’ depression. Kearney, Draper, and Baron (2005) examined 1,166 college students from 40 universities across America and found that Asian American students had the highest levels of psychological distress across all ethnic groups.

In addition, Gutierres and Van Puymbroeck (2006) believed that women who experience depression may use substances to cope with psychological distress related to and resulting from her depression. Supporting this notion, Franko et al. (2005) found that depression was primary to substance use and alcohol consumption in Asian American and White women. In a similar investigation of 4,300 Asian American high school students, Otsuki (2003) found that depression was significantly related to alcohol use. Although an increasing body of research has begun to indicate a relationship between depression and substance use among Asian American female adolescents, it is relatively unknown whether a similar relationship exists among Asian American college women.

PERCEIVED PEER USE

Research has also shown that peer substance use predicts personal substance use (Allen, Donohue, Griffin, Ryan, & Mitchell Turner, 2003). According to Peer Cluster Theory (Oetting & Beauvais, 1990), peers shape peer group behavior, values, attitudes, and norms about using or prohibiting drug use. Kim et al. (2002) tested this theory and found that peer use was strongly related to substance use among Asian American youth ages 11-14. Liu and Iwamoto (2007) also found that perceived peer use was a robust predictor of substance use among Asian American men. Although perceived peer use was found to be strongly related to substance use among Asian American men, it is unclear from the literature whether peer association and substance use holds true for Asian American women.

ASIAN CULTURAL VALUES

Cultural values have emerged as protective factors against substance use in previous studies (Unger et al., 2004). One way to conceptualize and measure an individual’s subscription to cultural values is through enculturation. Enculturation describes both the socialization process by which an Asian Americans endorse values indigenous to the culture and the degree to which the individual comes to endorse these values (Kim & Abreu, 2001). Although Asian Americans are not a homogeneous group and there is a great variation among the Asian ethnic group, Asian ethnic groups share some common cultural values and beliefs (Kim, Atkinson, & Umemoto, 2001). These indigenous Asian values include collectivism, filial piety (i.e., love and respect for family and taking care of parents), conformity to norms, emotional self-control, deference to authority, humility (i.e., minimize accomplishments), hierarchical relationships, and family recognition (Kim et al., 2001; Kim, Atkinson, & Yang, 1999). Strong adherence to Asian values may then decrease the probability of engaging in substance use/abuse behavior given the potential for the act to disgrace the individual’s family. For instance, individuals who adhere to the value of conformity to social norms also may be less likely to use substances because they might be more cautious to engage in this behavior due to lack of social sanctions (Liu & Iwamoto, 2007; Unger et al., 2004). Supporting this notion, Unger et al.’s (2002) study among culturally diverse high school students found that filial piety was related to lower risk of substance use. Therefore, endorsing cultural values might deter individuals from using substances.

Coping Strategies

Coping strategy is an important variable to investigate because it is a modifiable factor that can be incorporated into prevention programs. Coping strategies are often placed in two general categories: active (direct) coping methods (which involve problem-solving, social and emotional support-seeking, planning, positive reframing, reflection, and religion) and avoidant (indirect) coping styles (which involve forbearance, self-distraction, denial, surrender, behavioral disengagement, and substance use) (Lee & Liu, 2001). Several researchers (Lee & Liu, 2001; Liu & Iwamoto, 2007) have found evidence for this two-factor structure of coping among Asian American college students. However, a scant number of empirical investigations exist in the area of coping strategies and substance use among Asian Americans. Furthermore, previous findings have suggested that young women who use alcohol and other substances as a form of coping are at increased risk for substance abuse and mental health problems (Franko et al., 2005; Gutierres & Van Puymbroeck, 2006). In addition, college-age women’s use of other avoidant coping strategies may increase their susceptibility to pressure by their peers to use substances. Several studies have indicated that individuals who use active coping strategies are less likely to use substances whereas avoidant coping strategies lead to more negative outcomes (Snow, Sullivan, Swan, Tate, & Klein, 2006; Sullivan, Meese, Swan, Mazure, & Snow, 2005).

The Current Study

Previous research in the area of substance abuse among college students may have overlooked Asian Americans due to misconceptions of this ethnic group as a model minority with little risk for depression and substance abuse. However, research has demonstrated that Asian Americans, and Asian American women in particular, are also vulnerable to substance abuse and mental health problems (Franko et al., 2005; Gutierres & Van Puymbroeck, 2006). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to build on prior research that has identified protective and risk factors of substance use among Asian American college students. Specifically, this study examines the relationship between coping strategies, Asian values, depressive symptoms, perceived peer use, and substance use among Asian American college women. Coping strategies (i.e., active coping) and Asian values are of particular interest because, in theory, these variables are seen as potential protective factors; however, no studies have examined this among Asian American college women. Moreover, because depression is high among this population (Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls, 1998), it is of utmost importance to explore to the association between depressive symptoms and substance use.

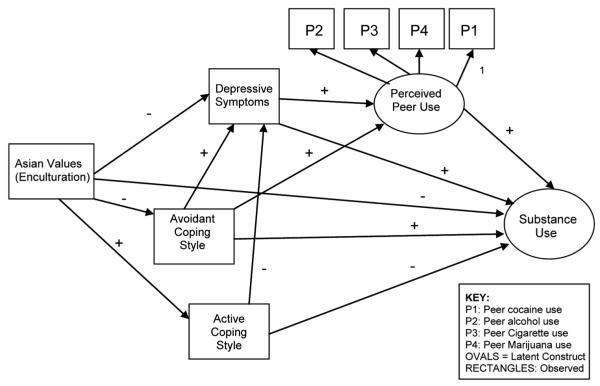

We hypothesize a substance use path model for Asian American college women that elucidate these relationships (Figure 1). Specifically, using framework presented in Figure 1, three separate path analysis will be performed: illicit drug use (i.e., a latent factor composed of marijuana, cocaine and other illicit drugs); alcohol use; and binge drinking. Based on previous literature (Allen et al., 2003; Kim, 2002; Otsuki, 2003), the authors first hypothesize that perceived peer use, depressive symptoms, and avoidant coping will be positively associated with substance use, whereas active coping strategies and Asian values will have an inverse relationship with substance use. In other words, we hypothesize that Asian American women are more likely to use substances if their peers also used substances, and that individuals who report more depressive symptoms and use avoidant coping strategies may attempt to engage in substance use to self-medicate and to forget about their problems. Individuals with higher endorsement of Asian values will be less likely to engage in substance use due to their collective-orientation value-system. Adhering to traditional Asian values of family recognition and conformity to social norms will therefore likely deter these individuals from engaging in substance use, thus serving as a protective factor. Individuals who use more active coping styles will also be less likely to use substances due to their tendency to utilize cognitive tools in problem solving (Sullivan et al., 2005; Tucker et al., 2005).

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized path model of substance use for Asian American college women.

Second, we hypothesize that there will be a link between depressive symptoms, coping styles, and perceived peer use. That is, individuals who use avoidant coping will be more likely to report depressive symptoms whereas those who use active coping strategies will be less likely to report depressive signs. Furthermore, we predict that individuals who report higher depressive symptoms may self-select in peer groups that use substance. Finally, based on Yeh, Inman, Kim, and Okubo’s (2006) research examining Asian Americans coping strategies used in response to 9/11, we predict an inverse relationship between Asian values and avoidant coping and a positive relationship between active coping and Asian values.

METHOD

Participants

Participants in this study were 167 Asian American college women, 50 whom identified as Chinese, 29 Korean, 27 Vietnamese, 19 Filipino, 18 “other Asian Americans,” 16 Asian Indian, and 8 Japanese. The mean age for participants was 20 years (SD = 2.53 years), of which 96.4% (n = 162) were undergraduates, and 3.6% (n = 6) identified as graduate students or other.

Measures

Substance use (otsuki, 2003)

Five substance use outcome items measured alcohol use, binge drinking behavior, marijuana use, cocaine, and “other” illicit drug use. These items were generated and based on items from the national surveys Multiethnic Drug and Alcohol Survey and American Drug Abuse and Alcohol Survey (Otsuki, 2003). Current alcohol use was assessed by the response to the question: “How often in the last month have you had alcohol to drink?” Binge drinking behavior was evaluated by the question: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours?” Marijuana use was measured by the question: “During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana.” Responses on alcohol use, binge behavior, and marijuana use in the past 30 days were rated on a 6-point ordinal categorical scale (0 = none, 1 = 1 or 2 days, 2 = 3-5 days, 3 = 6-9 days, 4 = 10-19 days, and 5 = 20 or more days). Cocaine use was evaluated by the question: “During the past 30 days, how many times did you use any form of cocaine, including powder, crack, or freebase?” Finally, the last substance use item was the question: “During the past 6 months, about how many times have you used ‘other substances’ (example: psychedelics, ecstasy or other substances) without a doctor’s orders?” Respondents rated the cocaine and other substances items on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = none, 1 = 1 to 2 times, 2 = a few times, 3 = once a month, 4 = once a week, 5 = a few times a week, 6 = once or more a day).

Perceived peer substance use

Perceived peer substance use consists of four items evaluating peer use in the following areas: friends’ use of alcohol, friends’ use of cigarettes, friends’ use of cocaine, and friends’ use of marijuana. Participants rated each item using the 4-point Likert scale: 1 = None, 2 = Few, 3 = Most, and 4 = All Friends. This peer substance use scale has been used by other researchers (Felix-Ortiz, Velazquez, Medina-Mora, & Newcomb, 2001; Otsuki, 2003).

Asian values scale-revised (avs-r) (kim & hong, 2004)

The AVS-R is a 25-item instrument designed to measure enculturation or the maintenance of one’s indigenous cultural values and beliefs. More specifically, the AVS-R assesses dimensions of Asian cultural values include “collectivism, conformity to norms, deference to authority figures, emotional restraint, filial piety, hierarchical family structure, and humility” (Kim & Hong, 2004, p. 19). Sample items include, “One should avoid bringing displeasure to one’s ancestors” and “One should consider the needs of others before considering one’s own needs.” The instrument uses a 4-point Likert scale (range, 1=strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). To obtain the AVS-R score, all 25 items are summed together and divided by 25. Higher scores indicate greater adherence to Asian cultural values.

Center of epidemiological studies-depression (ces-d) (radloff, 1977)

The CES-D is a widely used measure of depressive symptomatology. The CES-D consists of 20 items, and participants respond to each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = rarely or none of the time to 2 = most or all of the time. Higher scores on this instrument indicate greater depressive symptoms. In our study, the CES-D internal consistency estimate was α = .80.

Brief cope (carver, 1997)

The Brief Cope is a 28-item measure based on the full 60-item Cope instrument (Carver, Scheier, & Weintrub, 1989). This instrument is intended to assess how individuals cope with stressful events and consists of 14 subscales of coping. The 14 subscales of coping include: active coping, planning, positive reframing, acceptance, humor, religion, using emotional support, using instrumental support, self-distraction, denial, venting, substance use, behavioral disengagement, and self-blame. The Brief Cope uses a 4-point Likert scale (range, 1 = I haven’t been doing this at all to 4 = I’ve been doing this a lot). Carver (1997) reported reliability estimates range from α = .57 to .90 on the two-item subscales.

Dunkley, Blankstein, Halsall, Williams, and Winkworth (2000) and Lee and Liu (2000) hypothesized that Carver’s model could be conceptualized in a two-factor model: indirect (i.e., avoidant) and direct (active) coping. Accordingly, several researchers (Lee & Liu, 2001; Liu & Iwamoto, 2007) performed an exploratory factor analysis on the Brief Cope with an ethnically diverse sample of college students. Both research studies revealed a two-component model of coping: Cope-Direct and Cope-Indirect. The findings suggested that a two-factor model is theoretically simpler and more psychometrically sound than the two-item per subscales/factors proposed by Carver (1997).

We performed a principle axis factor analysis using a direct oblimin rotation on the 28 items in the Brief Cope because we expected that the factors might be correlated. Inspection of the eigenvalues greater than one, scree plot (Cattell, 1966), and interpretability of items loading on specific factors revealed that a two-factor model appeared to fit the data the best. Items that loaded less than .40 and items that cross-loaded were removed. The two coping items that included substance use were also removed from the analysis because of the risk of a spurious relationship with the substance use measures. From this procedure, 9 items were eliminated, resulting in 19 items total. These findings supported the use of a two-factor model: active coping (13 items) (i.e., “I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better” and “I’ve been getting help and advice from other people”), and avoidant coping (6 items) (i.e., “I’ve been saying to myself ‘this isn’t real,‘” and “I’ve been refusing to believe that it has happened”). The two-factor extraction accounted for 26% (active cope) and 15% (avoidant coping), respectively, yielding an item cluster similar to the two-factor model identified in previous studies (Lee & Liu, 2001; Liu & Iwamoto, 2007). This revised measure coping is both theoretically simpler and more psychometrically sound than the revision proposed by Carver (1997). We define active coping as an approach to stressful events that involves actively seeking ways to deal with and reduce one’s stress, whereas the avoidant coping approach involves implementing “strategies designed to adjust to stressful demands by changing the self rather than the situation (e.g., forbearance, self-destruction)” (Lee & Liu, 2001, p. 411). The internal consistency coefficients for active coping and avoidant coping were .85 and .77, respectively.

Procedure

After institutional review board approval was obtained, participants were recruited from undergraduate classes (Biology, Chemistry, Statistics, Asian American Psychology, and Engineering) at a large West Coast University. Data were collected from all of the students in the classes; however, only Asian American women were included in this current study. All participants completed the surveys voluntarily and were not given compensation for their participation. The survey packets consisted of the demographic questionnaire, substance use questions, peer use questions, the AVS-R (Kim & Hong, 2004), Brief Cope (Carver, 1997), and CES-D (Radloff, 1977). The participants took between 15 and 35 minutes to complete the survey packet. Ten participants had incomplete data (i.e., did not complete various measures) and were removed from the analysis.

RESULTS

Among the women in our sample, 47.9% (n = 80) reported consuming alcohol at least once in the past 30 days. Of these participants, 21.6% (n = 36) engaged in binge drinking and 10.8% (n = 18) of the participants who engaged in binge drinking drank 5 or more drinks at least 1 or 2 days, 6.6% (n = 11) between 3-5 days, 1.8% (n = 3) between 6-9 days day a month, and 2.4% (n = 4) more than 10 days in the past month. Approximately 10% (n = 16) of participants used marijuana; 6% (n = 10) of the participants used “other” illicit drugs (e.g., psychedelics, ecstasy, or other substances) and 3.6% (n = 6) reported cocaine use at least once in the past 30 days. It should be noted that the average score on the CES-D was 21.07 (SD = 8.26); more than 66% of the participants scored higher than the clinical cut-off score of 16 on the CES-D (Radloff, 1977). However, caution should be warranted in interpreting these resutls because the CES-D was not normed on Asian Americans. The means, standard deviations, ranges, zero-order correlations, and internal consistency estimates for all the variables are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations, Ranges, and Internal Consistency Estimates for the Substance Use Items, Perceived Peer Substance Use, Asian Values, Depressive Symptoms, Active and Avoidant Coping Scales Among Asian American College Women

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol use | – | .63** | .34** | .36** | .44** | .43** | .38** | .33** | .41** | −.10 | .16* | −.04 | .24** |

| 2. Binge drinking | – | – | .37** | .28** | .51** | .39** | .33** | .38** | .43** | −.04 | .08 | −.03 | .10 |

| 3. Marijuana use | – | – | – | .27** | .32** | .22** | .16* | .32** | .30** | −.05 | .13 | −.04 | .11 |

| 4. Cocaine use | – | – | – | – | .49** | .12 | .27** | .40** | .15 | −.11 | .21** | −.09 | .12 |

| 5. Other sub | – | – | – | – | – | .16* | .21** | .38** | .29** | .01 | .21** | −.04 | .13 |

| 6. Peer sub 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | .55** | .29** | .58** | −.02 | .02 | −.01 | −.03 |

| 7. Peer sub 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .46** | .51** | .05 | .10 | −.03 | .18* |

| 8. Peer sub 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .43 | .09 | .15 | .00 | .21** |

| 9. Peer sub 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .00 | .04 | .08 | .03 |

| 10. Asian values | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .01 | .07 | .08 |

| 11. Depression | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .02 | .52** |

| 12. Active cope | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .14 |

| 13. Avoid cope | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| M | 2.07 | 1.39 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 2.62 | 1.92 | 1.17 | 1.70 | 2.69 | 21.07 | 2.57 | 1.77 |

| SD | 1.43 | .90 | .83 | .30 | .46 | .77 | .66 | .38 | .64 | .19 | 8.26 | .57 | .57 |

| Range | 1–6 | 1–6 | 1–6 | 1–3 | 1–5 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 1–2 | 1–4 | 2–3 | 4–46 | 1–4.5 | 1–3 |

| α | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .80 | .80 | .85 | .77 |

Note. p < .05.

p < .01. Peer substance use (sub) 1 = peers who drink alcohol; peer sub 2 = peers who use cigarettes; peer sub 3 = peers who use cocaine; peer sub 4 = peers who use marijuana.

Path Analysis

Path analysis was performed using the structural equation modeling software Mplus version 4.0 software (Muthen & Muthen, 2006). Data screening was performed prior to conducting the path analysis. Missing values were handled using full maximum likelihood procedures to estimate parameters. Mardia’s test of multivariate normality indicated that the substance use outcomes were not multivariate normal, which was expected because the substance use variables were ordinal categorical variables and because the majority of participants did not report using illicit drugs. Weighted Least Squares Estimator was used given that this type of estimation can handle categorical variables, as well as variables that have unequal variance (Garson, 2008).

Measurement model

We subsequently tested the measurement model. In the measurement model, peer use and illicit drug use were the only latent constructs. Accordingly, the relationship between the peer use item parcels (e.g., friends’ use of alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, and cigarettes) and the latent constructs of perceived peer use/friends’ use of cocaine, marijuana, and cigarettes formed the latent factor. Friends’ use of cigarettes was included as an indicator because it is a commonly used peer use variable and has been shown to be associated with substance use (Simons-Morton, 2007). Consequently, a direct path from the item “friend’s use of cocaine” to latent perceived peer use was added and the loading was fixed to 1. The four observed indicators that formed the latent factor of illicit drug use were as follows: marijuana use, cocaine use, and other substances (i.e., using psychedelics, Ecstasy, or other substances without doctor’s orders) (Figure 1). Accordingly, the measurement model was tested and the fit indices comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), root mean square-error of approximation (RMSEA) were examined. CFI and TLI values greater than .95 and RMSEA values less than .05 indicate near model-to-data fit (Quintana & Maxwell, 1999). The measurement model showed good model fit, χ2 (2, n = 139) = 8.51, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, and RMSEA = .04.

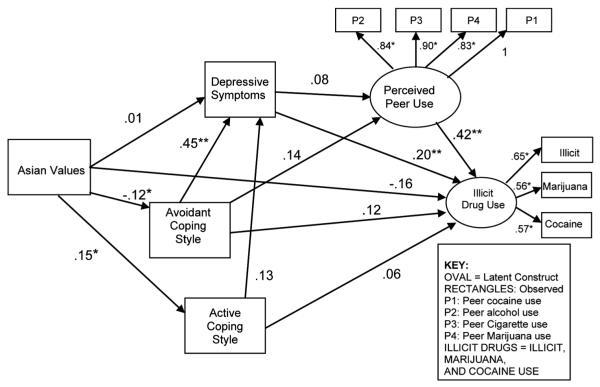

Illicit drug use model (figure 2)

FIGURE 2.

Weight least squares estimation illicit drug use path model of substance use for Asian American college women. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01.

A latent factor of illicit drug use was created using the observed substance use measures: cocaine, marijuana, and other illicit drug use. The rationale for creating a latent factor was because of the moderate correlations between the observed measures, as well as low frequency of substance use, thus identifying a latent factor of general illicit drug use was of greater interest. In addition, the use of multiple measures also reduces measurement error (Kline, 2005). Accordingly, the structural model for illicit drug use fit the data adequately, χ2 (10, n = 159) = 56.36, p = .02, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, and RMSEA = .06. The variance explained for illicit drug use was 33%. The following significant direct effects were found: perceived peer use (β = .42, p < .001), and depressive symptoms (β = .20, p < .01) to illicit drug use. These results suggest that individuals who experience higher levels of depressive symptoms and report that their peers use substances were found to be at elevated risk for illicit drug use.

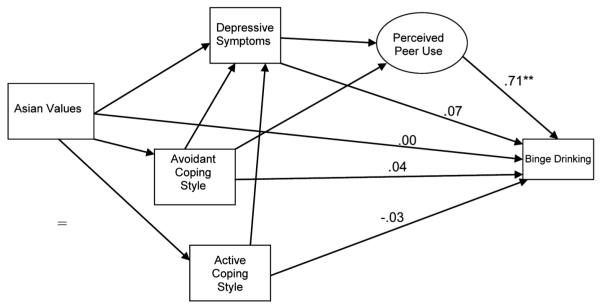

Binge drinking model

The model for binge drinking fit the data adequately, χ2 (10, n = 159) = 26.73, p = .14, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, and RMSEA = .05. percent Fifty-four of the variance explained was accounted for by the predictors of binge use (Figure 3). The only significant predictor of binge use was perceived peer use (β = .71, p < .001).

FIGURE 3.

Weight least squares estimation binge drinking path model of substance use for Asian American college women. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01; Factor loadings on Perceived Peer Use latent factor are the same as Figure 2.

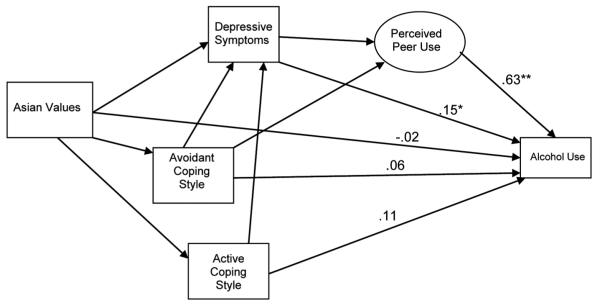

Alcohol use

The fit statistics for the path model for alcohol use in past 30 days indicates data fit the model well χ2 (10, n = 159) = 23.71, p = .26, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, and RMSEA = .05. Forty-seven percent of the variance in alcohol use was explained by the predictors in the model. The path from depressive symptoms (β = .15, p < .01) and perceived peer use (β = .63, p < .001) were the only significant predictors of alcohol use (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Weight least squares estimation alcohol use path model of substance use for Asian American college women. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01; Factor loadings on Perceived Peer Use latent factor are the same as Figure 2.

Predictors of depressive symptoms

Within the model of substance use, we were also interested in examining the predictors of depressive symptomatology. The variables in the model explained 21% of variance in depressive symptomatology. The results revealed that avoidant coping (β = .45, p < .001) was the only predictor of depressive symptoms. In other words, individuals who use avoidant coping may also be experiencing depressive symptoms.

Finally, Asian values were negatively associated with avoidant coping strategies and positively related to active coping. In effect, individuals with higher adherence to Asian values tended to use more active coping strategies and less avoidant coping strategies.

DISCUSSION

The current study addressed the gaps in research on substance use among Asian Americans by identifying risk factors for substance use and depressive symptoms among Asian American college women. Through a series of path analyses, we revealed how depressive symptoms and perceived peer substance use may help to explain substance use patterns among Asian American college women.

Perceived Peer Use

Our findings partially supported our model of substance use. As hypothesized, perceived peer use and depressive symptoms predicted illicit drug use. Perceived peer substance use was the most robust predictor of participant substance use in all three path models, which is consistent with previous studies (Allen et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2003; Liu & Iwamoto, 2007; Otsuki, 2003). In other words, participants in this sample were significantly more likely to report illicit drug use and consume alcohol when they reported that their peers used substances. These results are consistent with Liu and Iwamoto’s (2007) finding that perceived peer use was the strongest predictor of substance use among Asian American men. These findings lend support to peer cluster theory, which indicates that participants who use substances may associate with and select peers who have similar habits and beliefs, reinforcing each other’s substance use behaviors (Kim et al., 2003; Simons-Morton, 2007). Specifically, it may be the social norms, attitudes, and substance use behaviors established within the friendship that reinforce the normalcy of their substance use and abuse (Simons-Morton, 2007). In addition, when individuals associate with peers who use substances, the availability of substances might become more available, increasing the likelihood of using. Our hypothesis that individuals who report depressive symptoms and use avoidant coping would be positively associated to perceived peer use was not supported. It could be that regardless of whether an individual uses avoidant coping strategies or is experiencing depressive symptoms, these coping styles will not increase the likelihood of associating with peers who use substances or vice versa.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were found to be directly related to illicit drug use and alcohol consumption but not to binge drinking. These findings are consistent with previous studies linking depression with substance use among women (Franko et al., 2005; Otsuki, 2003). This finding has significant clinical implications given that Asian American women between the ages of 18 to 24 have been found to have the highest rates of depression (Commonwealth Fund Survey for Girls, 1998). This population may then be at an increased risk for substance abuse. One possible explanation is that individuals who report high depressive symptomatology may use illicit drugs and alcohol as a form of dealing with their negative mood, placing these women at heightened susceptibility to experimenting with substances (Otuski, 2003). Specifically, illicit drugs and alcohol might provide them with a temporary outlet to alleviate depressive symptomatology. Conversely, it should be noted that because alcohol is a depressant (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2003), the physiological effects of alcohol consumption can include psychological symptoms reflective of depressive symptoms. Although a relationship between these two variables was found, the directionality of the relationship is speculative at best because this study was cross-sectional, thus caution is warranted in interpreting these results. Contrary to our hypothesis, no relationship was found between depressive symptoms and binge drinking. This finding could reflect binge drinking’s association with social activity or partying behavior (Wechsler et al., 2000). For example, individuals might be more inclined to binge drink when they are in the presence of their peers, specifically when they perceive that their peers use.

Avoidant coping was the only predictor of depressive symptoms among participants. One possible explanation for this finding is that a bidirectional relationship exists between avoidant coping and depressive symptoms. Specifically, individuals experiencing depressive symptoms are also attempting to deal with their symptoms by engaging in coping strategies, such as using distracting behaviors or denial strategies. Conversely, when individuals use avoidant coping such as self-blame or self-criticism, these strategies might contribute to decreased self-worth, increasing reported depressive symptomatology.

Asian Values

Contrary to our hypothesis, Asian values (measured using the AVS) did not serve as protective factors against illicit drug use, alcohol consumption, and binge drinking for the women in the current study. One explanation could be that Asian American women in psychological distress are overwhelmed and turn to peer support networks to alleviate some of this distress. It may be more likely that peers are using substances to cope with distress rather than explicitly using cultural values. These external or behavioral means of coping allow Asian American women to distract themselves rather than focusing internally on their cultural values and worldview.

Coping Strategies

We hypothesized that individuals with active coping styles would be less likely to use substances than those using avoidant coping. In the correlational analysis, there was a relationship between avoidant coping and alcohol consumption; however, in the path analysis, the effects became non-significant. Thus, the results did not support our hypothesis that coping strategies predict substance use. Although some women in previous studies were at greater risk of using substances when they used certain coping strategies (Tucker et al., 2005), these findings were not replicated in this study. It appears that the women who use substances use them regardless of their coping strategies. In regards to Asian values predicting active and avoidant coping, our hypothesis was supported. The higher AVS adherence the greater active coping strategies were used while individuals who had lower AVS tended to use more avoidant coping strategies. One explanation for why individuals might tend to have greater connection with others and activity seek support could be because active coping items taps into social support (i.e., “I’ve been getting help and advice from other people”; Carver, 1997) and AVS taps into collectivism.

Limitations

The current study was limited in several ways. First, the results were cross-sectional and therefore preclude any assumption of causality. Second, the researchers recognize that Asian Americans are a heterogeneous group; therefore, there are possible within-group differences. However, given that we had unequal ethnic group sizes, we were unable to conduct analysis that examined ethnic group differences. Future studies should use large sample sizes of Asians to examine within and between group differences because previous findings have suggested that some Asian ethnic groups have greater substance use than others (Otuski, 2003). Another limitation was the length of the survey (which took approximately 15 to 35 minutes to complete), which may have affected some participants’ ability to complete the entire survey and reduced the size of the current sample. The use of convenience sampling yielded a relatively small number of participants (n = 167), reducing the statistical power. Regional differences in substance use and abuse patterns, coping styles, and Asian value adherence or idiosyncratic characteristics of the current sample should also be considered when interpreting these results. Therefore, caution is warranted in generalizing these findings. Future studies should address different substance use and abuse patterns among specific Asian ethnic groups, as well as examine possible generational status differences in substance use.

Implication for Clinical Practice

Findings from this study suggest that contrary to the model minority myth, Asian American women do experience psychological distress such as depression, and that their use of substances, especially alcohol, is an important factor to consider in treatment. As clinicians work with Asian American women, an accurate assessment of their peer group and peer’s use of substances is a good indicator of current or potential substance use. In particular, the more likely the peer group is actively engaged in substance use, the more likely the Asian American woman will be as well. It may be that binge drinking is a type of social activity that normalizes excessive drinking. Thus, for clinicians, it may be important to assess the frequency of binge drinking among Asian American women and assess the client’s impression of the consequences of binge drinking.

As clinicians assess the Asian American woman’s peer network, it may be important to assess the diversity (i.e., level of enculturation, racial and ethnic diversity) of her peer network. It may be that low enculturation to Asian cultural values also means a low identification to other Asian Americans with high Asian cultural values; instead, the Asian American woman may be associating with peers who have a higher tolerance for substance use and abuse. Clinicians and psychoeducational workshop leaders should emphasize the strength of peer influence in decisions about whether to use substances, describe ways in which individuals can proactively avoid compromising situations where they will not feel compelled to use, and provide coping strategies for resisting peer pressure to use drugs and alcohol. Similarly, given the strong link between perceived peer use and substance use, this lends further support for social norms campaigns that educate individuals about the normative drinking behavior within the college (White & Jackson, 2004/2005). Furthermore, given that active coping may serve as a protective factor of depression and illicit drug use, counseling sessions and workshops could teach or recommend campus resources that teach active coping strategies to implement in response to stress.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a supplemental grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01-DA018730). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institute of Health.

REFERENCES

- Allen M, Donohue WA, Griffin A, Ryan D, Mitchell Turner MM. Comparing the influence of parents and peers on the choice to use drugs. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2003;30:163–186. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;58:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. The screen test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls . The Commonwealth Fund. William T. Grant Foundation; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, Blankstein KR, Halsall J, Williams M, Winkworth G. The relationship between perfectionism and distress: Hassles, coping, and perceived social support as mediators and moderators. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:437–453. [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz M, Velazquez JV, Medina-Mora ME, Newcomb MD. Adolescent drug use in Mexico and among Mexican American adolescents in the United States: environmental influences and individual characteristics. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:27–46. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Thompson D, Barton BA, Dohm F, Kraemer HC, Iachan R, et al. Prevalence and comobidity of major depressive disorder in young black and white women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;39:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garson D. Structural equation modeling. 2008 Retrieved from http://www2.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/pa765/structur.htm#ordinaldata.

- Glendhill-Hoyt J, Lee H, Strote J, Weschler H. Increased use of marijuana and other illicit drugs at US college in the 1990s: results of three national studies. Addiction. 2000;95:1655–1667. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierres SD, Van Puymbroeck C. Childhood and adult violence in the lives of women who misuse substances. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:497–513. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Corbin W, Fromme K. Trajectory classes of heavy episodic drinking among Asian American college students. Addiction. 2010;105:1912–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ja DY, Yuen FK. Substance abuse treatment among Asian Americans. In: Lee E, editor. Working with Asian Americans: A guide for clinicians. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1997. pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- James WH, Kim GK, Moore DD. Examining racial and ethnic differences in Asian adolescent drug use: The contributions of culture, background, and lifestyle. Drugs: Education, Prevention, & Policy. 1997;4:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Volume I: Secondary school students. Volume II: College students & adults. (NIH publication nos. 03-5375; 03-5376) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2003. Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney LK, Draper M, Baron A. Counseling utilization of college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:272–285. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Abreu JM. Acculturation Measurement: Theory, current instruments, and future directions. In: Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of multicultural counseling. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. pp. 394–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Atkinson DR, Umemoto D. Asian cultural values and counseling process: Current knowledge and directions for future research. The Counseling Psychologist. 2001;29:570–603. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Atkinson DR, Yang PH. The Asian Values Scale: Development, factor analysis, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Hong S. A psychometric revision of the Asian Values Scale using the Rasch model. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2004;37:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Liu HTT. Coping with intergenerational family conflict: Comparison of Asian American, Hispanic, and European American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:410–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Liu HTT, Eo E. Perceptions of substance abuse problems in Asian American communities by Chinese, Indian, Korean, and Vietnamese populations. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse. 2003;2:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM. The study of men and masculinity as an important multicultural competency consideration. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:685–697. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Chang T. Asian American men and masculinity. In: Leong F, Inman A, Ebreo A, Yang L, Kinoshita L, Fu M, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Iwamoto D. Asian American men’s gender role conflict: The role of Asian values, self-esteem, and psychological distress. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2006;7:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Iwamoto DK. Conformity to masculine norms, Asian values, coping strategies, peer group influences and substance use among Asian American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2007;8:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado MM. The invisible family: Counseling Asian American substance abusers and their families. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families. 2000;8:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4th ed. Authors; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Aoki B, Huang K, Morris A, Nguyen H, Wong W. Drug use behaviors among Asian drug users in San Francisco. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:823–838. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Adolescent drug use: Findings of national and local surveys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:385–394. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki T. Substance use, self-esteem, and depression among Asian American adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:369–390. doi: 10.2190/RG9R-V4NB-6NNK-37PF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Maxwell SE. Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist. 1999;27:485–527. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B. Social influence on adolescent substance use. American Journal of Health Behaviors. 2007;31:672–684. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.6.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow DL, Sullivan TP, Swan SC, Tate DC, Klein I. The role of coping and problem drinking in men’s abuse of female partners: Test of a path model. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:267–285. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So DW, Wong FY. Alcohol, drugs, and substance use among Asian-American college students. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38:35–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Okazaki S. Asian-American education experience. American Psychologist. 1990;45:913–920. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Meese KJ, Swan SC, Mazure CM, Snow DL. Precursors and correlates of women’s violence: Child abuse traumatization, victimization of women, avoidance coping, and psychological symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, D’Amico E, Wenzel S, Golinelli D, Elliott M, Williamson S. A prospective study of risk and protective factors for substance use among impoverished women living in temporary shelter settings in Los Angeles County. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Teran L, Huang T, Hoffman BR, Palmer P. Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of adolescents. Addiction Research and Theory. 2002;10:257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Basezconde-Garbanati L, Shakib S, Palmer PH, Mora J. A cultural psychology approach to “Drug Abuse” prevention. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:1779–1820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers KS, Patten CA, Bronars C, Lane K, Stevens SR, Croghan IT, et al. Binge drinking in female college students: The association of physical activity, weight concerns, and depressive symptoms. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53:13–140. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.3.133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson T, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health college alcohol study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Jackson K. Social and psychological influences on emerging adult drinking behavior. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004-2005;28:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Davies PT. Depression and heavy alcohol use among adolescents: Concurrent and prospective relations. Developmental and Psychopath-ology. 1999;11:823–844. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong F, Halgin R. The “Model Minority”: Bane or blessing for Asian Americans? Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2006;34:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yang PQ. Illegal drug use among Asian American youths in Dallas. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2002;1:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CJ, Inman AC, Kim AB, Okubo Y. Asian American families’ collective coping strategies in response to 9/11. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:134–148. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J, Daniel AM. Substance abuse among Vietnamese American college students. College Student Journal. 2001;35:13–27. [Google Scholar]