Abstract

Background

Daily hemodialysis has been associated with surrogate markers of improved survival among hemodialysis patients. A potential disadvantage of daily hemodialysis is that frequent vascular access cannulations may affect long term vascular access patency.

Methods

The study design was a four-year, non-randomized, contemporary control, prospective study of 77 subjects in either 3 hour daily hemodialysis (6 dialysis treatments weekly of 3 hours each; n = 26) or conventional dialysis (3 dialysis treatments weekly of 4 hours each; n = 51). Outcomes of interest were vascular access procedures (fistulagram, thrombectomy and access revision).

Results

Total access procedures (fistulagram, thrombectomy and access revision) were 543.2 (95%CI: 432.9, 673.0) per 1000 person-years in the conventional dialysis group versus 400.8 (95%CI: 270.2, 572.4) per 1000 person-years in the daily hemodialysis dialysis group (incidence rate ratio= 0.74 with 95%CI: from 0.40 to 1.36, P = 0.33), after adjusting for age, gender, diabetes status, serum phosphorus, hemoglobin level and erythropoietin dose, there was no significant differences in incidence rate of total access procedures (P value >0.05). There was no difference in time to first access revision between the daily dialysis and the conventional dialysis groups after adjustment for covariates (hazard ratio=0.99 95% CI: 0.42, 2.36, P = 0.96).

Conclusions

Daily hemodialysis is not associated with increased vascular access complications, or increased vascular access failure rates.

Keywords: Daily hemodialysis, vascular access

Introduction

Daily hemodialysis has been associated with favorable surrogate markers of improved survival among hemodialysis patients. These outcomes include improvements in left ventricular mass index, chronic inflammation, nutritional markers and mineral metabolism markers [1–5]. There is currently no study that addresses directly the impact of daily dialysis on vascular access outcomes over long term follow-up. Previous observational and uncontrolled studies of daily hemodialysis have shown mixed results in regards to vascular access outcomes with the majority showing no difference in access outcomes [5–9] and some showing a trend toward improved access outcomes [4, 10–12]. The randomized controlled FHN study of daily, in-center, hemodialysis showed no significant differences in access outcomes, but a trend toward more access procedures with similar patency rates [13]. Importantly, no controlled studies have addressed this issue over a long-term follow-up of greater than one year.

A potential source of morbidity and possibly mortality from daily hemodialysis is vascular access failure as vascular access complications can have grave consequences [14, 15]; therefore, it is important to determine the effects of frequent cannulation on the vascular access. Arteriovenous grafts may be especially susceptible to early failure since punctures in the grafted material may weaken and eventually undermine the integrity of the access. A secondary consideration is the potential for increased medical costs if daily dialysis increases the number of access procedures necessary to maintain access patency. Patient acceptance of daily dialysis therapies may be impaired if the effects on vascular access patency are unknown since access complications are also a significant source of patient morbidity through pain associated with procedures and increased hospitalizations due to access failure. Finally, since arteriovenous fistulae are associated with improved survival in epidemiological studies [16], failure of the arteriovenous access may lead to increased mortality rates.

This particular study aimed to investigate the impact of daily dialysis on vascular access complications. We hypothesized that frequent dialysis cannulation would be associated with either increased or similar rates of vascular access complications. To test this hypothesis we performed a non-randomized, prospective cohort study with contemporary control of daily hemodialysis versus conventional hemodialysis and examined vascular access outcomes. With increased adoption of daily dialysis regimens it is important to determine the long term effects of daily hemodialysis on access survival, since little is known regarding the potential for vascular access harm related to frequent cannulation.

Methods

Study Participants

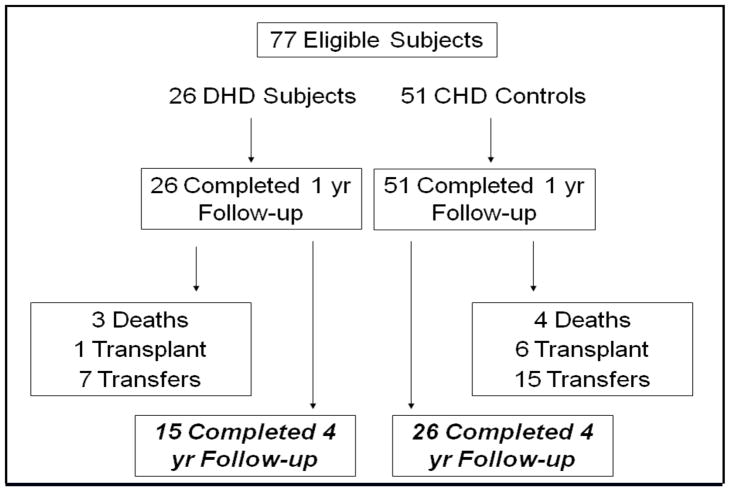

All participants were adult patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis at Dialysis West at the Texas Diabetes Institute, San Antonio, Texas. Subjects were followed up to 48 months. The Bexar County Hospital District approved the prospective enrollment of twenty-six patients in the short daily hemodialysis program. The only eligibility criterion was willingness to participate in the short daily hemodialysis program, and no patient was excluded. A total of 108 patients were screened for enrollment and short daily hemodialysis was offered to all patients. Spaces were consecutively offered to 36 patients who agreed to participate on a voluntary basis until 26 enrollees was reached. At that time, 51 contemporary conventional hemodialysis patients from the original 108 eligible patients were selected on the basis of similar baseline characteristics (age, gender, etiology of renal disease, co-morbidity burden, vascular access, medications and time on dialysis) (Figure 1). Fifteen patients in the daily hemodialysis group completed 4 year follow-up and remained on six times weekly dialysis. Patients were censored at death, transplant or transfer to a non-participating dialysis unit. Following completion of one year of daily dialysis, daily dialysis was offered to all subjects and 8 subjects from the conventional dialysis cohort began daily hemodialysis. A sensitivity analysis was performed in which subjects that crossed over were excluded from analysis and the results were comparable to the original results.

Figure 1.

Study Design

The study design was a non-randomized, prospective cohort study. Subjects were followed until the time when one of the following occurred: transfer to a non-participating dialysis unit, kidney transplantation, death or end of study follow-up. Vascular access events were recorded in a prospective manner. Subjects were censored at the time of transfer, transplant or end of follow-up. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Dialysis treatments in both groups utilized polysulfone, non-reuse, high flux dialyzers (Optiflux 2000, Fresenius); blood flows were 400 ml per minute and dialysate flows were 800 ml per minute. Subjects in the daily hemodialysis group received six dialysis treatments per week, 3 hours each treatment; those in the conventional dialysis group received 3 treatments per week of 4 hours each treatment. Adjustments were made to dialysate bath, dry weight and medications including erythropoietin, phosphate binders, vitamin D sterols, and intravenous iron by the treating nephrologists in order to achieve K/DOQI guidelines for control of blood pressure, anemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism [17]. Aside from the increased frequency of dialysis visits in the daily hemodialysis group, there was no difference in the frequency of clinic visits or monitoring of laboratory values in either group.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were summarized by mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were shown. Wilcoxon’s Rank Sum test was used for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables between patients with conventional dialysis or with daily dialysis. The unadjusted relationship between the treatment group and time to first access procedure was examined using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess the independent relationship and to adjust for potential confounding by age, gender, serum phosphorus, diabetes status, hemoglobin level and erythropoietin dose. To compare the rate of access procedure during follow-up time between the two groups, Poisson regression was used with Huber-White sandwich variance estimator accounting for over-dispersion. By recognizing the observed imbalance between the groups due to a small sample size, propensity score analysis was conducted to control for a potential bias due to imbalance between two treatment groups. Propensity score adjustment preserved statistical power by reducing confounders into a single variable. Propensity scores were estimated as the logit of a binary logistic regression predicting probability of being assigned into daily hemodialysis group as a function of other risk factors including age, gender, serum phosphorus, diabetes status, hemoglobin level and erythropoietin dose. Then the propensity score was added as a covariate in the multivariable models to further evaluate the adjusted effect of treatment group on outcomes (propensity adjusted model). A sensitivity analysis was performed in which subjects with catheters were excluded from analysis and there was no significant change in the results. All the analysis and calculations were done using R version 2.10.0 (www.r-project.org). All statistical inferences were assessed at a 2-sided 5% significant level.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Characteristics of patients with conventional hemodialysis dialysis (n=51) and patients with daily hemodialysis dialysis (n=26) are shown in Table 1. As we have reported previously in this cohort [1], patients in two treatment groups were of similar age, sex, medication use, smoking status, baseline vascular access, co-morbidity status and time on dialysis, but patients in the daily dialysis group had higher serum phosphorus and lower hemoglobin levels compared to patients in the conventional hemodialysis group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Daily Hemodialysis (N=26) | Conventional Hemodialysis (N=51) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 65 | 67 | 0.91 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | 0.46 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4 | 0 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4 | 6 | |

| Hispanic | 92 | 92 | |

| Other | 0 | 2 | |

| Vascular Access, % | 0.75 | ||

| Arteriovenous Fistula | 60 | 53 | |

| Arteriovenous Graft | 36 | 39 | |

| Central Venous Catheter (Tesio type) | 4 | 8 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 77 | 69 | 0.45 |

| Khan risk group, % | NS | ||

| Low | 0 | 0 | |

| Medium | 26.9 | 31.4 | |

| High | 73.1 | 68.6 | |

| Diagnosed hypertension, % | 96 | 100 | 0.16 |

| Dialysis vintage, yrs | 2.81 ± 2.98 | 3.87 ± 2.97 | |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dL | 6.26 ± 2.57 | 4.98 ± 1.49 | 0.0006 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 3.96 ± 0.40 | 4.06 ± 0.26 | NS |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 10.8 ± 1.93 | 12.7 ± 1.31 | 0.01 |

| History of smoking % | 42.3 | 45.1 | NS |

| Medication use, % | NS | ||

| Beta Blocker | 73.1 | 74.5 | |

| Statin | 100 | 100 | |

| ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker | 100 | 100 | |

| Calcium channel blocker | 42.3 | 43.1 | |

| Vasodilator | 11.5 | 27.5 |

Variables are shown as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Wilcoxon’s rank sum test was used for comparing continuous variables, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test.

Frequency of Total Vascular Access Procedures

There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of frequency distribution of dialysis access interventions (P = 0.68). In the daily hemodialysis group 13 (50%) subjects had no thrombectomies, 8 (31%) had one, 5 (19%) subjects had 2–4 and no subjects had 5 or more. In the conventional dialysis group, 30 subjects (58%) had no thrombectomies, 10 subjects (20%) had 1, 6 subjects (12%) had 2–4 interventions and 5 subjects (10%) had 5 or more.

Rates of Fistulagram, Thrombectomy and Access Revision

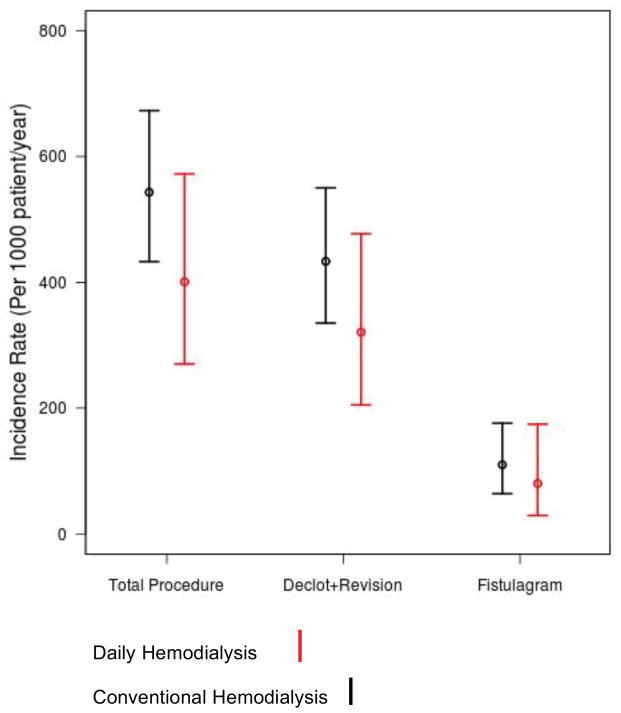

There were no significant differences in the rates of vascular access procedures between the daily hemodialysis and conventional hemodialysis groups (Figure 2). During 4-year follow-up, the rate of access procedure (thrombectomy, fistulagram or revision) was 543.2 (95%CI: 432.9, 673.0) per 1000 person-years in the conventional dialysis group versus 400.8 (95%CI: 270.2, 572.4) per 1000 person-years in the daily hemodialysis dialysis group (incidence rate ratio= 0.74 with 95%CI: from 0.40 to 1.36, P = 0.33). There was one access revision in the daily dialysis group and seven access revisions in the conventional dialysis group (P=0.25) during follow-up. In the conventional dialysis group there was 388 (95%CI: 296.0, 499.7) thrombectomies per 1000 person/year versus 307.3 (95%CI: 194.5, 461.3) thrombectomies per 1000 person/year in the daily dialysis group (incidence rate ratio=0.79 with 95%CI: from 0.39 to 1.60, P = 0.51). Finally, the incidence of fistulagram was comparable between groups (incidence rate ratio=0.73 with 95%CI: from 0.15 to 3.53, P=0.69). After adjusting for age, gender, serum phosphorus, diabetes status, hemoglobin level and erythropoietin dose, there was no significant differences as regards to incidence rate of total access procedures, access revisions, thrombectomies and fistulagrams between treatment groups (all P values >0.05).

Figure 2.

Access procedure rate by treatment groups and procedure type.

Time to first access procedure and Vascular Access status at follow-up

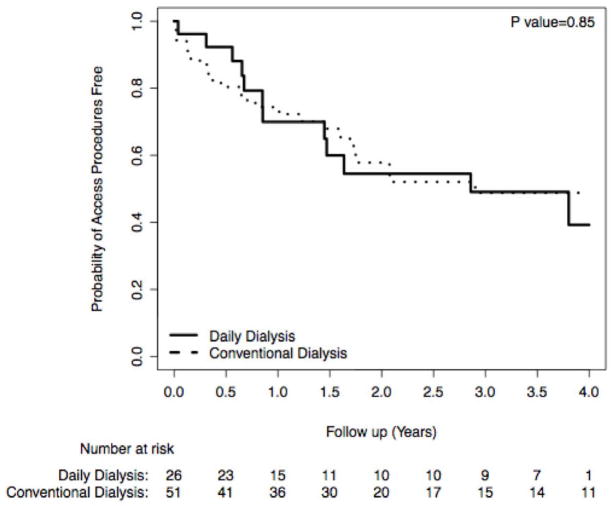

Both in univariate analysis (log rank P=0.85) and multivariable adjusted analysis (hazard ratio=0.99; 95% CI, 0.42–2.36, P=0.96), no statistically significant difference between the participants from the conventional dialysis and patients from daily hemodialysis group was found with regard to time to first access procedure (Figure 3). At the end of 4 year follow-up, there were no central venous catheters in the daily dialysis group and there were 63% fistulas and 37% arteriovenous grafts. Of the eleven fistulas at four year follow-up all had used the button-hole technique. No clinically significant pseudoaneurysms developed in either group.

Figure 3.

Erythropoietin doses, hemoglobin and blood pressure

As previously reported in this cohort [1] erythropoietin dose in the daily dialysis group decreased from 15,000 (IQR: 6250 to 24,500) units per treatment to 9443 (IQR: 6313 to 14,795) units per treatment at one year follow-up (P <0.01); whereas in the conventional dialysis group erythropoietin dose remained stable over one year follow-up 8450 (IQR: 5025 to 14,813) units per treatment at baseline and 11,167 (IQR: 6300 to 16,398) units per treatment at one year follow-up, (P >0.05) [1]. At four year follow-up, erythropoietin dose in the daily hemodialysis group remained unchanged at 9188 ± 4594 units per treatment and in the conventional dialysis group erythropoietin doses remained unchanged at 9530 ± 7365 units per treatment (P > 0.05). As previously reported [1] hemoglobin in the daily dialysis group increased from 10.8 ± 1.9 g/dl to 12.7 ± 1.0 g/dl (P < 0.001); whereas, hemoglobin in the conventional dialysis group was more favorable at baseline and remained stable (12.7 ± 1.3 g/dl at baseline and 12.0 ± 0.7 g/dl at follow-up, P > 0.05). At four year follow-up, hemoglobin in the daily hemodialysis remained unchanged at 13.2 g/dl (P > 0.05) and unchanged in the conventional dialysis group at 12.8 g/dl (P > 0.05). At four year follow-up serum albumin remained stable in the daily hemodialysis group (3.96 g/dl ± 0.40 g/dl at baseline and 4.08 ± 0.23 g/dl at 4 year follow-up) as well as in the conventionally dialysis group (4.06 g/dl ± 0.26 g/dl at baseline and 3.94 ± 0.25 g/dl at 4 year follow-up).

As previously reported in this cohort [1], in the daily dialysis group systolic blood pressure remained similar between baseline and one year follow-up 145 ± 13 mmHg to 142 ± 11 mmHg (P > 0.05). At 4 year follow-systolic blood pressure in the daily dialysis group decreased to 128 ± 18 (P < 0.05). In the conventional dialysis group systolic blood pressure remained unchanged at baseline (143 ± 12 mmHg), one year follow-up (145 ± 12 mmHg) [1] and at 4 year follow-up (148 ± 23 mmHg) (P > 0.05). In the daily dialysis group diastolic blood pressure remained similar between baseline and one year follow-up 73 ± 7.7 mmHg to 73 ± 7.1 mmHg [1]. At 4 year follow-up diastolic blood pressure in the daily dialysis group decreased to 60 ± 4 (P < 0.05). In the conventional dialysis group diastolic blood pressure remained unchanged at baseline (75 ± 9.1 mmHg), one year follow-up (75 ± 6.8 mmHg) [1] and at 4 year follow-up (71 ± 13 mmHg) (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

We found in a long term, controlled study that in-center, daily hemodialysis was not associated with increased rates of vascular access procedures or vascular access failure. These findings are of clinical interest as enthusiasm for quotidian hemodialysis therapies has been increasing over the last decade.

There is some controversy in the previous literature on the issue of vascular access complications in association with daily hemodialysis. Previous observational studies and uncontrolled studies had noted either trends toward improved vascular access outcomes with short daily dialysis therapies [4, 10–12] or no significant differences in vascular access outcomes [5–9]. These studies are limited by their uncontrolled nature and short term follow-up. The NIH sponsored Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trial (FHN) showed in a randomized clinical trial a reduction in left ventricular mass index at one year as well as improvements in quality of life [13]. In this trial, a non-significant trend towards increased vascular access complications was also noted, although follow-up was only one year [13]. It is important to note that in the FHN study, the rates of vascular access failure were not higher in the daily hemodialysis group, only a non-significant trend toward increased vascular access procedures was noted. It is possible that this only reflects increased referrals for procedures during this trial related to more frequent visits to the hemodialysis clinic, since the more objective outcome of access failure did not show a difference.

Our study observes vascular access complications in a controlled manner over a 4 year duration of follow-up. We observed a non-significant trend toward improved vascular access survival which seemed to be most apparent in the first year of follow-up, although overall access survival rates were similar overall. It is important to point out that there are some differences between our study and the FHN study. Dialysis times among patients dialyzing daily were significantly longer in the current study (180 minutes per session, versus 154 minutes in the FHN study) [13] and therefore solute clearances would be expected to be higher. Additionally, the length of follow-up in our study was different and that may affect the vascular access outcomes as well and could potentially explain the difference between our findings and the FHN study. We found that in addition to no differences in time to first vascular access procedure (Figure 3) the numbers of dialysis access procedures was not increased by daily dialysis (Figure 2). This suggests that the underlying access abnormalities such as venous outflow stenosis are not affected by frequent cannulations. In fact there was a non-significant trend toward fewer thrombectomy procedures in the daily dialysis group.

The pathobiology of vascular access failure is currently not well elucidated. Arteriovenous graft failure and thrombosis and late arteriovenous fistula failure share similar mechanisms as venous outflow obstruction seems to play a prominent role in both of these pathogenic processes [18]. Neointimal hyperplasia characterized by vascular smooth muscle and hyperplastic myofibroblasts expressing growth factors and inflammatory cytokines play a prominent role in venous outflow stenosis [19–23]. Current theories on the source of neointimal expansion include local infiltration of myofibroblast through the vessel adventitia as well as localization of progenitor cells of bone marrow origin that then participate in the process [24–28]. As it appears that the ratio of endothelialization to intimal expansion determines the degree of outflow stenosis, repeated cannulation of the access site which has been implicated in release of local cytokines may stimulate this process [29]. Therefore, it would reason that repeated cannulation would have harmful effects on access survival. Our results suggest that repeated cannulations may not be the most important factor in propagating venous outflow stenosis.

In observational clinical studies several clinical factors not directly related to the number of cannulations have been implicated in vascular access failures. Among these are decreased fetuin A levels [30], poor nutritional markers [31] and pulse pressure [32] and therefore numbers of cannulations may only be one of a myriad of variables that affect access survival. We have shown previously that inflammatory and nutritional markers are improved with three-hour daily dialysis [1, 2]. It is plausible that the reduction in chronic inflammation and improvements in nutritional markers are responsible for favoring vascular access survival and this may negate any effect of the frequent cannulation. Also, the theoretical harm of frequent cannulation may simply be overstated and that factors such as the inflammatory, uremic milieu and vessel shear stress may play more prominent roles in determining vascular access survival.

The main strengths of this study are the four year duration of follow-up, the use of a contemporary control group and the high prevalence of co-morbidities among subjects which is reflective of the general United States ESRD population. Among the limitations are the non-randomized study design; therefore, even though potential confounders were adjusted for in our analysis, residual bias cannot be excluded. Another limitation was that our sample size was modest which did limit our statistical power to detect a difference between groups. Furthermore, it is conceivable that subjects undergoing daily hemodialysis paid more attention to access care and that increased use of techniques such as buttonhole techniques could have affected outcomes. Finally, there was relative overrepresentation of Hispanic Americans relative to the general ESRD population which may impact the generalizability of our results.

In summary, our study demonstrates that in long term follow-up, daily hemodialysis is not associated with increased vascular access complications. As the increased adoption of frequent dialysis therapies continues; this study shows that frequent cannulation of either arteriovenous fistulae or arteriovenous grafts is not deleterious which should reassure patients not to defer or resign from daily therapy out of fear of vascular access complications. As frequent hemodialysis regimens gain increased acceptance and adoption, our results demonstrate long term safety in terms of access outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Research support: During the course of the study, Dr. Ayus was supported by NIH Grant U01 DK066481, and Dr. Achinger was supported by an NIH T32 Training Grant.

Footnotes

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 2010 meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

References

- 1.Ayus JC, Mizani MR, Achinger SG, Thadhani R, Go AS, Lee S. Effects of short daily versus conventional hemodialysis on left ventricular hypertrophy and inflammatory markers: a prospective, controlled study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;9:2778–2788. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayus JC, Achinger SG, Mizani MR, et al. Phosphorus balance and mineral metabolism with 3 h daily hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2007;71:336–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Achinger SG, Mizani MR, Ayus JC. Use of 3-hour daily hemodialysis and paricalcitol in patients with severe secondary hyperparathyroidism: A case series. Hemodial Int. 2010;14(2):193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traeger J, Galland R, Delawari E, Arkouche W, Hadden R. Six years’ experience with short daily hemodialysis: do the early improvements persist in the mid and long term? Hemodial Int. 2004;8:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2004.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AW, Chebrolu SB, Ing TS, et al. Early clinical, quality-of-life, and biochemical changes of “daily hemodialysis” (6 dialyses per week) Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(1):90–102. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds JT, Homel P, Cantey L, et al. A one-year trial of in-center daily hemodialysis with an emphasis on quality of life. Blood Purif. 2004;22(3):320–328. doi: 10.1159/000079186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martins Castro MC, Luders C, Elias RM, Abensur H, Romao Junior JE. High-efficiency short daily haemodialysis--morbidity and mortality rate in a long-term study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(8):2232–2238. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piccoli GB, Bermond F, Mezza E, et al. Vascular access survival and morbidity on daily dialysis: a comparative analysis of home and limited care haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(8):2084–2094. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ting GO, Kjellstrand C, Freitas T, Carrie BJ, Zarghamee S. Long-term study of high-comorbidity ESRD patients converted from conventional to short daily hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):1020–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Leypoldt JK, Nelson N, Kutner NG, Cheung AK. A crossover study of short daily haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(1):166–175. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twardowski ZJ. Blood access in daily dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2004;8(1):70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2004.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods JD, Port FK, Orzol S, Buoncristiani U, Young E, Wolfe RA, Held PJ. Clinical and biochemical correlates of starting “daily” hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 55(6):2467–76. 199. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chertow GM, Levin NW, Beck GJ, et al. In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2287–2300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayus JC, Sheikh-Hamad D. Silent infection in clotted hemodialysis access grafts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(7):1314–1317. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V971314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nassar GM, Ayus JC. Infectious complications of the hemodialysis access. Kidney Int. 2001;60(1):1–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzo V, Martn M, Rufino M, Hernandez D, Torres A, Ayus JC. Predialysis nephrologic care and a functioning arteriovenous fistula at entry are associated with better survival in incident hemodialysis patients: an observational cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(6):999–1007. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eknoyan G, Levin NW, Eschbach JW, et al. Continuous quality improvement: DOQI becomes K/DOQI and is updated. National Kidney Foundation’s Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(1):179–194. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(01)80074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy-Chaudhury P, Sukhatme VP, Cheung AK. Hemodialysis vascular access dysfunction: a cellular and molecular viewpoint. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1112–1127. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss MF, Scivittaro V, Anderson JM. Oxidative stress and increased expression of growth factors in lesions of failed hemodialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(5):970–980. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(05)80013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy-Chaudhury P, Kelly BS, Miller MA, et al. Venous neointimal hyperplasia in polytetrafluoroethylene dialysis grafts. Kidney Int. 2001;59(6):2325–2334. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rekhter MD, Gordon D. Active proliferation of different cell types, including lymphocytes, in human atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol. 1995;147(3):668–677. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swedberg SH, Brown BG, Sigley R, Wight TN, Gordon D, Nicholls SC. Intimal fibromuscular hyperplasia at the venous anastomosis of PTFE grafts in hemodialysis patients. Clinical, immunocytochemical, light and electron microscopic assessment. Circulation. 1989;80(6):1726–1736. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.6.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stracke S, Konner K, Kostlin I, et al. Increased expression of TGF-beta1 and IGF-I in inflammatory stenotic lesions of hemodialysis fistulas. Kidney Int. 2002;61(3):1011–1019. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sata M, Saiura A, Kunisato A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into vascular cells that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2002;8(4):403–409. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott NA, Cipolla GD, Ross CE, et al. Identification of a potential role for the adventitia in vascular lesion formation after balloon overstretch injury of porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 1996;93(12):2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.12.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, O’Brien JE, Jr, Mannion JD, et al. Remodeling of autologous saphenous vein grafts. The role of perivascular myofibroblasts. Circulation. 1997;95(12):2684–2693. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, O’Brien JE, Fard A, Mannion JD, Wang D, Zalewski A. Adventitial myofibroblasts contribute to neointimal formation in injured porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 1996;94(7):1655–1664. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diao Y, Guthrie S, Xia SL, et al. Long-term engraftment of bone marrow-derived cells in the intimal hyperplasia lesion of autologous vein grafts. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(3):839–848. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albers FJ. Causes of hemodialysis access failure. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1994;1(2):107–118. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(12)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HY, Chiu YL, Chuang YF, et al. Association of low serum fetuin A levels with poor arteriovenous access patency in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(4):720–727. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gagliardi GM, Rossi S, Condino F, et al. Malnutrition, infection and arteriovenous fistula failure: Is there a link? J Vasc Access. 2010;12(1):57–62. doi: 10.5301/jva.2010.5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou CY, Liu JH, Kuo HL, et al. The association between pulse pressure and vascular access thrombosis in chronic hemodialysis patients. Hypertens Res. 2009;32(8):712–715. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]