Abstract

Purpose

To examine the prevalence and potential risk factors associated with substance use in adolescents with eating disorders (EDs).

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 290 adolescents, ages 12 –18 years, who presented for an initial ED evaluation at The Eating Disorders Program at The University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) between 2001 and 2012. Several factors, including DSM-5 diagnosis, diagnostic scores, and demographic characteristics were examined. Multinomial logistic regression was used to test associations between several factors and patterns of drug use for alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and any substance.

Results

Lifetime prevalence of any substance use was found to be 24.6% in those with anorexia nervosa (AN), 48.7% in bulimia nervosa (BN), and 28.6% in eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). Regular substance use (monthly, daily, and bingeing behaviors) or a substance use disorder (SUD) was found in 27.9% of all patients. Older age was the only factor associated with regular use of any substance in the final multinomial model. Older age and non-White race was associated with greater alcohol and cannabis use. Although binge-purge frequency and BN diagnosis were associated with regular substance use in bivariate analyses, gender, race and age were more robustly associated with substance use in the final multinomial models.

Conclusions

Co-morbid substance use in adolescents with EDs is an important issue. Interventions targeting high-risk groups reporting regular substance use or SUDs are needed.

Keywords: adolescents, eating disorders, substance use, substance use disorder, cannabis, alcohol, tobacco, bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, DSM-5

Introduction

Several studies in the adult literature have reported an association between substance use disorders (SUDs) and eating disorders (EDs), with substance abuse present in 12–18% of adults with anorexia nervosa (AN) and 30–70% of those with bulimia nervosa (BN).1 Significantly fewer adolescents meet criteria for SUDs. However, the relationship between risky substance use and EDs in a clinical population of adolescents has not been well-examined, despite the fact that problems with eating and substances typically both begin during this developmental period.

There are many common symptoms associated with EDs and risky substance use, including disruption of appetite and satiation, cravings, preoccupation with food, self-destructive behavior, denial, and serious medical consequences.2–4 Research might suggest that risky substance use would differ across EDs, given significant differences in their presentation. For example, AN is often characterized by obsessive-compulsive traits, whereas BN is typically better characterized by loss of control. This loss of control, in addition to increased emotional and behavioral dysregulation, has been hypothesized to account for bingeing behavior and corresponding rates of substance abuse.5 Indeed, impulsive eating and purging behavior frequently precedes substance use.6 The similarities shared by those with EDs and SUDs suggest a common etiology and may be explained by overlapping genetic, neurochemical, cultural, and social risk factors.7,8 These data suggest that addressing the underlying psychopathology in both these disorders may be critical, and treatment in adolescence may prevent deterioration in ED and SUD symptoms. However, few treatment programs address both EDs and substance use,3 despite the fact that co-occurrence results in greater morbidity and mortality.9

To date, only four peer-reviewed studies have examined adolescent substance use in clinical samples of EDs. The available literature suggests that approximately two thirds of adolescents with BN have used alcohol and about one third have used tobacco at least once.10,11 Another third have used illegal drugs at least once, with marijuana being the most common, followed by cocaine and amphetamines.10 Across adolescent AN and BN patients, binge-purge behavior was associated with risky tobacco, alcohol, and other substance use, compared to those with restrictive eating patterns.12 Similarly, girls with bulimic symptoms (i.e. binge eating/purging behavior) had higher rates of substance use than those with primarily restrictive patterns.11 Indeed, 30% of girls with BN had smoked cigarettes, used marijuana, and were drinking alcohol at least weekly.11

Qualitative research has found that adolescents with EDs typically use substances to relieve anger, avoid eating, “get away,” and relax.13 Adolescents with binge-purge behaviors used substances more frequently than adolescents with restrictive ED patterns, but both used substances less frequently than the general adolescent population. Two similar studies looking at ED patients with substance use reported associations between substance use and impulsive behavior (ie. stealing, self-harm, attempted suicide)11 as well as addictive features and psychopathological symptoms (ie. delinquent behavior, aggression, inattention).12 These findings reflect a similar trend found in the adult literature.

The present study examines the prevalence of substance use by ED diagnosis, including eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). In addition, demographic characteristics, co-morbid clinical characteristics, and ED-specific characteristics were examined in relation to pattern of use.

We hypothesized that adolescents with more frequent binge-purge behavior, including those with BN, would be more likely to use alcohol and other substances. We also expected that other characteristics associated with BN, including higher percent of expected body weight (%EBW) and less eating restraint would be associated with greater substance use. Consistent with previous research,14–16 we expected older age, non-White race, non-intact family status, anxiety, and depression to be strongly associated with heavier substance use.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from 359 patients, ages 12 – 18 years, who presented to the Eating Disorders Program at The University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) for evaluation between September 2001 and April 2012. They were mostly parent- or physician- referred. Eleven cases were missing substance use evaluations, 48 did not have enough substance use documentation, and 10 did not meet criteria for an ED, and thus were dropped. The final sample consisted of 290 cases.

Procedures

All assessments were completed during the intake appointment before the start of treatment and typically lasted 3 hours. Written consent for adult patients or parental/guardian consent and patient assent for child/adolescent patients were obtained. Refusal to consent did not alter patients’ assessment or treatment in the clinic. The use of these data was approved by the UCM Institutional Review Board.

Measures

During the initial diagnostic interview, information on the following characteristics was collected: age, gender, race, family structure (intact vs. not), %EBW, ED diagnosis, severity of eating disorder psychopathology (restraint, eating concern, shape concern, weight concern), number of binge/purge episodes in the past 3 months, anxiety disorder diagnosis, and depressive symptoms. Age at the time of initial evaluation was used, and any substance use reported within a few months of evaluation was included. A trained research assistant measured weight and height of all participants using a calibrated digital or balance-beam scale. All patients were weighed in light indoor clothing. Percent EBW was calculated based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.

In addition, the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) was administered to assess ED diagnosis, severity of eating disorder psychopathology, and binge/purge episode frequency. Scores on the EDE were used to categorize ED diagnoses based on more inclusive DSM-5 criteria, which our research group had adopted prior to the manual’s publication.17 The Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) was also administered and used to determine co-morbid anxiety disorder diagnosis and frequency of substance use. Finally, participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depressive symptoms.

Eating Disorder Examination

(Fairburn & Cooper, 1993).18 The EDE assesses behavioral and cognitive symptoms of EDs using a semi-structured investigator-led interview. Its scores have good validity, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability.19,20 Cognitive symptoms are assessed within a 28-day time frame on a seven point Likert scale (0 to 6), with higher scores indicating greater pathology. Behavioral frequency scores represent actual frequencies of each behavior over the past three months. Together, these yield four subscales with the following Cronbach alphas in this sample: Restraint (.80), Eating Concern (.75), Weight Concern (.82), and Shape Concern (.92).

The EDE generates DSM-IV ED diagnoses with good reliability in adolescents,21 and recent research demonstrates it can also generate DSM-5 diagnoses with relatively high sensitivity and specificity.17 Given that some adolescents would meet DSM-5 but not DSM-IV criteria for AN or BN, we used the diagnostic algorithm described by Berg et al. to re-categorize adolescents.17 EDNOS was recoded as AN if %EBW was below 85, importance of shape or weight was rated ≥ 4, and fear of weight gain was rated ≥ 4 or compensatory behaviors occurred at least once per week. EDNOS was recoded as BN if %EBW was at least 85 and both objective binge episodes and compensatory behaviors occurred at least once per week.

Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS)

The K-SADS is a semi-structured interview, used to evaluate the presence of substance use and other psychiatric disorders at baseline, according to DSM-IV criteria. It has good validity and high inter-rater reliability.22 All questions were asked of the child/adolescent patient. With regard to cigarette use, patients were asked about ever and current use, the greatest amount, the age of regular use, and attempts to quit. Questions specific to alcohol use are aimed at pattern of use (quantity and frequency), and concern from others about drinking. Specific drug use questions ask if patients have ever used cannabis, stimulants, sedative/hypnotics, cocaine, opioids, PCP, hallucinogens, solvents/inhalants, or other drugs. Any affirmative answer about drug use was followed by questions about frequency.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI is a twenty-one item self-report questionnaire designed to assess depressive symptoms, with scores ranging from 0 to 63.23 Scores over 18 indicate moderate to severe depressive symptoms. It has been used in several adolescent ED populations, has good psychometric properties, and strongly correlates with clinical depression.24–26 The Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was .92.

Evaluation of Patterns of Substance Use

SUD classification has changed significantly since the collection and classification of this data. Thus, SUD diagnoses were based on DSM-IV criteria, for which very few patients qualified. Details of substance use in patients who did not meet criteria for a SUD were gleaned from the K-SADS interview and notes from their treatment, and these were categorized into the following clinically meaningful categories of substance use: never used, rarely used (i.e. patient describes “trying” or “experimenting” once or twice), or regularly used (frequencies included monthly, daily, or repeated binge use). A similar grouping for risky use in teens has been used in previous studies,12,27,28 and regular use by this categorization has been found to indicate increased risk of developing mood symptoms and disruptive behavior disorders.27

Statistical Analyses

A chi-square test was used to determine if the proportion of adolescents who had regularly used any substances vs. never used (independent variable) varied significantly according to ED diagnostic category (AN, BN, and EDNOS—dependent variables). Use of “any” substance included alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, sedative hypnotics, cocaine, opioids, PCP, hallucinogens, solvents/inhalants, and other drugs (including prescription stimulants, nitrous oxide, ecstasy, and MDA). The most commonly used substances were examined in separate chi-square analyses, including alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco.

In addition, univariate multinomial logistic regressions were used to evaluate each independent variable (i.e. demographic factors, ED diagnosis, anxiety disorder, BDI, %EBW, EDE scores) as a predictor of each dependent variable (occasional or regular use vs. non-use) of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and any substances. Factors for which the overall model was significant at p < 0.07 were entered into a final multivariate multinomial analysis for each of the four substance categories. The dependent variables were pattern of use (occasional or regular use) compared to non-use. SPSS 19.0 package was used for statistical analysis.

Results

The majority of participants were female (90.7%, n = 263), with a mean age of 15.77 ±1.84 years. Most self-identified as White (79.7%, n = 231). The remainder were Black (14.5%, n = 42), Asian (1.4%, n = 4), and Other (2.4%, n = 7). Twenty-eight (9.7%) participants identified as Latino and 256 were Non-Hispanic Whites. There were missing race and ethnicity data on 6 patients. Based on DSM-5, 118 (40.7%) patients met criteria for AN, 37 (12.8%) for BN, and 135 (46.6%) met criteria for EDNOS.

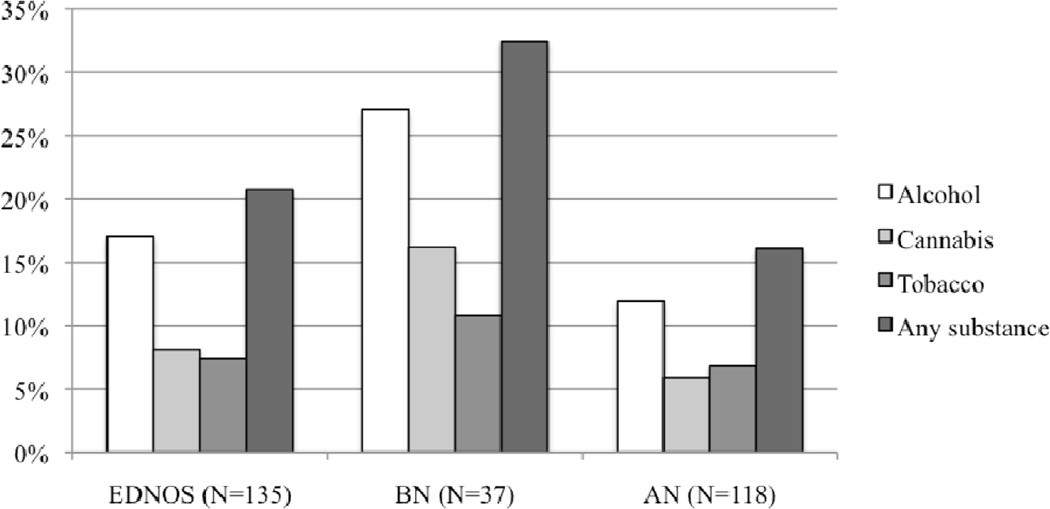

Most reported never using substances (69.3%, n = 201). Lifetime prevalence of substance use was found in roughly a quarter (24.6%, n = 30) of AN, one half (48.7%, n = 19) of BN, and a third (28.6%, n = 40) of EDNOS patients. Regular substance use was found in all diagnostic categories: AN (16.1%, n = 19), BN (32.4%, n = 12), and EDNOS (20.7%, n = 28). Figure 1 shows the proportion of ED adolescents with regular substance use by ED diagnosis. Pattern of substance use did not differ across ED diagnostic groups except for tobacco (χ2 = 13.551, p = .009), such that adolescents with BN were more likely than those with AN to have used tobacco at least once (rare use) compared to those who had never used substances (B = 1.872, SE = 0.574, OR = 6.500, p = .001). The highest proportion of regular use was found among adolescents with BN, but chi-square tests examining differences between diagnostic groups for regular use were non-significant.

Figure 1. The proportion of Eating Disordered Adolescents with Regular Substance Use out of N = 290 by Diagnosis.

NB: chi-square tests examining differences between diagnostic groups for regular use versus no use were non-significant.

In general, alcohol was the most commonly consumed substance followed by cannabis, tobacco, and cocaine. Of those patients who reported using alcohol, approximately one quarter of them (27.5%, n = 22) described binge drinking. Street drugs were reported at relatively low frequencies, including LSD, mushrooms, ecstasy, and inhalants. A few patients also reported abusing prescription medications: THC pills, sedative hypnotics, opiates, and stimulants on a few occasions.

Only 17 (5.9%) adolescents met full criteria for substance abuse. Cannabis was the most commonly abused substance, followed by alcohol. Other substances of abuse included prescription stimulants, painkillers, and cocaine. Five (1.7%) patients met criteria for dependence with cannabis (n = 3) and alcohol (n = 2).

Univariate Analysis

Univariate models for alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and any substance compared individuals with rare or regular use to those who had never used (reference category). Overall results from the univariate analyses are listed in Table 1. Older age and more frequent binge/purge episodes were significantly associated with use of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and any substance (p ≤ .05). Non-White race was also associated with greater alcohol and cannabis use (p ≤ .05). Eating disorder diagnosis (BN) and eating-related concerns were significantly associated with increased tobacco and any substance use (p ≤ .07). Having greater shape-related concerns and non-intact family status were factors specific to tobacco use (p ≤ .07). Male gender was associated specifically with cannabis use (p ≤ .06). Weight-related concerns, eating restraint, %EBW, anxiety diagnosis, and depressive symptoms were not significant or marginally significant (p ≥ .07).

Table 1.

Relationship of Socio-demographic Characteristics, Family Structure, ED diagnosis and severity, anxiety, and depression with Four Substance Categories Using Univariate Multinomial Logistic Regression (N= 290)

| Any Substance | Alcohol | Cannabis | Tobacco | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p-value | χ2 | p-value | χ2 | p-value | χ2 | p-value | |

| Age | 25.821 | 0.001* | 24.293 | 0.001* | 9.662 | 0.008* | 7.545 | 0.023* |

| Female Gender | 0.726 | 0.695 | 0.827 | 0.661 | 5.677 | 0.058* | 0.775 | 0.679 |

| Race | 4.142 | 0.126 | 6.224 | 0.045* | 10.541 | 0.005* | 1.388 | 0.499 |

| Intact family | 1.349 | 0.509 | 2.533 | 0.282 | 2.196 | 0.334 | 5.511 | 0.064* |

| ED diagnosis | 8.933 | 0.063* | 5.568 | 0.234 | 6.348 | 0.175 | 13.551 | 0.009* |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.972 | 0.373 | 1.756 | 0.416 | 4.859 | 0.088 | 1.690 | 0.430 |

| BDI | 2.845 | 0.241 | 1.214 | 0.545 | 0.160 | 0.923 | 0.238 | 0.888 |

| %EBW | 0.181 | 0.914 | 0.965 | 0.617 | 0.679 | 0.712 | 0.906 | 0.636 |

| EDE Score | 6.67 | 0.04* | 3.57 | 0.17 | 5.12 | 0.08 | 10.12 | 0.01 |

| EDE (Weight subscale) | 5.281 | 0.071 | 2.900 | 0.235 | 3.245 | 0.197 | 3.134 | 0.209 |

| EDE (Shape subscale) | 5.070 | 0.079 | 2.806 | 0.246 | 3.128 | 0.209 | 7.840 | 0.020* |

| EDE (Restraint subscale) | 0.746 | 0.689 | 0.613 | 0.736 | 0.283 | 0.868 | 5.175 | 0.075 |

| EDE (Eating subscale) | 6.673 | 0.036* | 3.567 | 0.168 | 5.118 | 0.077 | 10.116 | 0.006* |

| BP 3m | 6.957 | 0.031* | 5.833 | 0.054* | 8.067 | 0.018* | 13.628 | 0.001* |

p<0.07 covariate included in final multinomial model; ED = eating disorder; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; %EBW = percent expected body weight; EDE = eating disorder examination; BP 3m = Binge-purge frequency over past three months

Multinomial Logistic Regression

In the final model examining any substance use, for every one-year increase in age, the OR of substance use was 1.37 (p = .029) for rare and 1.85 (p = .001) for regular use. Age was not associated with ED diagnosis (p = .13), eating-related concerns (p = .51), or binge/purge frequency (p = .14).

For alcohol, regular (OR = 1.9, p = .001) but not rare use (p = .083) was strongly associated with increasing age. Although race did not remain significant in the overall model (p = .058), non-White youth were more likely to be regular (p = .018) alcohol users compared to White youth.

For cannabis, several significant findings were observed in the final model including age (p = .001), race (p = .002), and gender (p = .024), but not binge/purge frequency (p = .37). For every one-year increase in age, the OR increased by 1.7 for both rare (p = .004) and regular cannabis use (p = .011). Non-White adolescents had an OR of 5.9 (p = .001) for rare and 4.8 (p = .019) for regular cannabis use. Boys were 9.1 times (p = .008) more likely to regularly use cannabis compared to girls, with no significant difference for rare use.

For tobacco, only non-intact family status (p = .064) remained marginally significant. Age (p = .34), eating disorder diagnosis (p = .51), eating-related concerns (p = .41), shape-related concerns (p = .92), and binge-purge frequency (p = .23) were not significant in the final model. This marginal finding showed a trend of adolescents from non-intact families being 3.9 times more likely to regularly use tobacco (p = .026).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest clinical study of adolescent substance use within an ED sample, and the only study to compare patterns of use by DSM-5 ED diagnoses. One important finding is that 28% of adolescents had regular substance use or a SUD. Regular substance use in adolescents is important to understand because it can lead to substance dependence, interpersonal conflict, and greater psychiatric comorbidity during this transition to adulthood.28 Therefore, understanding factors associated with regular and risky substance use is needed because early detection and targeted treatment can prevent increased morbidity.

In general, the most frequently used substances were alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco. Cannabis was the most commonly abused substance in those with SUDs, which is consistent with previous reports.11,12 Interestingly, the overall prevalence of SUDs in our sample (6%) was lower than that found in an outpatient study of psychiatrically referred adolescents, ages 13–19 years (11%).29 This may reflect the unique clinical presentation of AN, which comprised about 40% of our sample. Adolescents with AN tended to be younger in this sample, and they generally restricted all forms of substances, including food and alcohol.

Lifetime prevalence of alcohol use was relatively low (27.6%) in our sample compared to reports from a national survey of adolescents (59.8%) with a similar mean age.28 This finding has been replicated in other studies in ED populations.13 Our analyses also matched reported national trends of increased regular alcohol, marijuana, or any substance use with increased age, and a greater proportion of older teens reporting regular use and even substance abuse and dependence.28,30

BN diagnosis was strongly associated with regular alcohol consumption. However, BN patients had a lower lifetime prevalence of alcohol use (40.5%) compared to BN samples from older studies with a similar mean age (66–67%).10,11 This may reflect differences in race and ethnicity, as well as the impact of loosened DSM-5 criteria for BN. The more inclusive criteria for BN in DSM-5 resulted in an increase in patients with these diagnoses who were previously diagnosed with EDNOS. Patients with less frequent binge/purge behavior may demonstrate a less severe form of BN correlating with lower impulsivity and risk-taking behavior associated with substance use. Supporting this hypothesis is that greater frequency of binge-purge episodes was associated with more frequent use of alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and any substance in the univariate analyses.

The findings for adolescents with higher binge-purge frequencies were robust for tobacco and cannabis, and have been found in previous studies.11,12 The prevalence of tobacco (35.1%) and cannabis (29.7%) use in our patients with BN was very similar to that found in previous research.11,12 Furthermore, tobacco use was significantly more frequent in patients with BN compared to AN. Although tobacco’s appetite suppressant property may help with food restriction in AN, our clinical observation is that adolescents with AN are often too inhibited to put anything in their mouths, including cigarettes. As they transition to adulthood, the clinical picture for AN often changes, coinciding with greater access to substances, including tobacco, which may be used to modulate appetite. Greater tobacco use was also associated with disrupted families, which has also been reported in other studies.14,31 In fact, male adolescents from single-parent households have been shown to be at greatest risk for several problem behaviors, including tobacco and cannabis use.32 Gender differences in socialization processes may place male adolescents under greater pressure to use substances.33 It is unclear why males in our sample were at greater risk for regularly using cannabis but not tobacco. It is possible that males with eating disorders may present differently than males in the general population, or alternatively our small sample of males may have limited our power to detect differences.

Also consistent with previous research was our finding that racial and ethnic minorities were at higher risk of alcohol and illicit drug use, including cannabis.16 With regard to alcohol, White teens were less likely to have used alcohol compared to other races, which differs from a national survey of teens showing Blacks less likely to have used alcohol. However, another national study found that those racial/ethnic minorities who used substances were more likely than Whites to transition later to drug abuse with dependence.28,34

Several studies have associated cannabis use with anxiety disorders and BN.27,35 Previous reports have demonstrated co-morbid anxiety disorders in BN as high as 64 to 71%.35,36 We expected to find anxiety disorders to be associated with regular cannabis use, but this trend was non-significant. In a larger community cohort, frequent cannabis use in adolescent girls was found to predict later depression and anxiety, with daily cannabis users having the highest risk.37 Other studies have examined endocannabinoid involvement in nutrient intake and processing. Anxiety and BN may share a common etiology based on dysregulation of cannabinoid pathways, as endocannabinoid derangement is thought to contribute to development of EDs.38,39 Ultimately, age, gender, race, and family structure were stronger, independent factors associated with substance use compared to ED diagnosis or frequency of binge-purge episodes.

The main limitation of this study is that the sample consisted of adolescents seeking ED treatment in a specialized center, limiting the ability to generalize results to other ED populations. Furthermore, even though substance use was evaluated by structured interview, participants likely minimized their use. This study was also limited by the absence of a control group, thus we are unable to draw conclusions about what substance use looks like in adolescents seeking treatment for other psychiatric disorders. In addition, using data from K-SADS—a broad-based structured psychiatric interview—limited the ability to draw comparisons with substance abuse specific questionnaires on adolescents. Lastly, the cross-sectional design does not allow evaluation of timing in development of substance use, which would have provided more insight into the etiology of SUDs in adolescents with EDs.

Despite these limitations, this is the largest clinical study of its kind, examining patterns of substance use based on DSM-5 ED diagnoses using gold-standard measures for eating disorders (EDE), general psychopathology (K-SADS), and well-established self-report measures. Future research should examine development of co-morbid SUDs over time, treatments, and practice parameters.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jon Grant, J.D., M.D. and Gustavo Bitdinger, M.S. for their input on our manuscript.

This work was supported by MH079979 (Dr. Le Grange) and T32 MH082761 (Drs. Le Grange and Accurso) from NIMH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: There are no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additionally the authors report the following financial disclosures: Dr. Karnik: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR000431). Dr. Le Grange: royalties from Guilford Press and Routledge, and honoraria from the Training Institute for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders, LLC.

Implications and Contributions

With more than a quarter of our sample regularly using substances, these findings highlight the importance of co-morbid substance use and the potential need for dual-intervention in a subset of adolescents with EDs. Clinicians should consider factors associated with frequent use: older age, binge-purge frequency, male gender, and family structure.

References

- 1.Pisetsky EM, Chao YM, Dierker LC, May AM, Striegel-Moore RH. Disordered eating and substance use in high-school students: results from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Int J Eat Disord. 2008 Jul;41(5):464–470. doi: 10.1002/eat.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brewer S. Eating Disorders as Addictions. Newburyport, MA: The Carlat Psychiatry Report; 2012. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Author. Clients with substance use and eating disorders. Rockville: Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrop EN, Marlatt GA. The comorbidity of substance use disorders and eating disorders in women: prevalence, etiology, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2010 May;35(5):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Carter FA, Joyce PR. Lifetime comorbidity of alcohol dependence in women with bulimia nervosa. Addict Behav. 1997 Jul-Aug;22(4):437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blinder B, Blinder M, Sanathara V. Eating Disorders and Addictions. Minneapolis, MN: Psychiatric Times; 1998. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper S. Chemical Dependency and Eating Disorders: Are They Really so Different? J Counseling & Development. 1989;68:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holderness CC, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Co-morbidity of eating disorders and substance abuse review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1994 Jul;16(1):1–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199407)16:1<1::aid-eat2260160102>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearlstein T. Eating disorders and comorbidity. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2002;4(3):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer S, le Grange D. Comorbidity and high-risk behaviors in treatment-seeking adolescents with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2007 Dec;40(8):751–753. doi: 10.1002/eat.20442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiederman MW, Pryor T. Substance use and impulsive behaviors among adolescents with eating disorders. Addict Behav. 1996 Mar-Apr;21(2):269–272. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro-Fornieles J, Diaz R, Goti J, et al. Prevalence and factors related to substance use among adolescents with eating disorders. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16(2):61–68. doi: 10.1159/000268106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock SL, Goldberg E, Corbett S, Katzman DK. Substance use in female adolescents with eating disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2002 Aug;31(2):176–182. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledoux S, Miller P, Choquet M, Plant M. Family structure, parent-child relationships, and alcohol and other drug use among teenagers in France and the United Kingdom. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002 Jan-Feb;37(1):52–60. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: predictors and substance abuse outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002 Feb;70(1):67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vega WA, Zimmerman RS, Warheit GJ, Apospori E, Gil AG. Risk factors for early adolescent drug use in four ethnic and racial groups. Am J Public Health. 1993 Feb;83(2):185–189. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg KC, Stiles-Shields EC, Swanson SA, Peterson CB, Lebow J, Le Grange D. Diagnostic concordance of the interview and questionnaire versions of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2012 Nov;45(7):850–855. doi: 10.1002/eat.20948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2004 Jan;35(1):80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2000 Nov;28(3):311–316. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<311::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binford RB, Le Grange D, Jellar CC. Eating Disorders Examination versus Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire in adolescents with full and partial-syndrome bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Jan;37(1):44–49. doi: 10.1002/eat.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, et al. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview. Test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985 Jul;42(7):696–702. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory. 1987:iv, 25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrera M, Jr, Garrison-Jones CV. Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening instrument for adolescent depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1988 Jun;16(3):263–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00913799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashani JH, Sherman DD, Parker DR, Reid JC. Utility of the Beck Depression Inventory with clinic-referred adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990 Mar;29(2):278–282. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199003000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Moye A, Bryson SW, Jo B. Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;67(10):1025–1032. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. Pediatrics. 2003 Jun;111(6 Pt):e699–e705. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swendsen J, Burstein M, Case B, et al. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Apr;69(4):390–398. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Abrantes AM, Spencer TJ. Clinical characteristics of psychiatrically referred adolescent outpatients with substance use disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Jul;36(7):941–947. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young SE, Corley RP, Stallings MC, Rhee SH, Crowley TJ, Hewitt JK. Substance use, abuse and dependence in adolescence: prevalence, symptom profiles and correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002 Dec 1;68(3):309–322. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glendinning A, Shucksmith J, Hendry L. Family life and smoking in adolescence. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(10):93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Scheier LM, Diaz T, Miller NL. Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000 Jun;14(2):174–184. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rienzi BM, McMillin JD, Dickson CL, et al. Gender differences regarding peer influence and attitude toward substance abuse. J Drug Educ. 1996;26(4):339–347. doi: 10.2190/52C7-5P6B-FPH2-K5AH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fryar CDMM, Hirsch R, Porter KS. Smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use reported by adolescents aged 12–17 years: United States, 1999–2004. National Health Statistics Reports. 2009;15:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Carter FA, Joyce PR. Lifetime anxiety disorders in women with bulimia nervosa. Compr Psychiatry. 1996 Sep-Oct;37(5):368–374. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godart NT, Flament MF, Lecrubier Y, Jeammet P. Anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity and chronology of appearance. Eur Psychiatry. 2000 Feb;15(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. BMJ. 2002 Nov 23;325(7374):1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matias I, Bisogno T, Di Marzo V. Endogenous cannabinoids in the brain and peripheral tissues: regulation of their levels and control of food intake. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006 Apr;30(Suppl 1):S7–S12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monteleone P, Matias I, Martiadis V, De Petrocellis L, Maj M, Di Marzo V. Blood levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide are increased in anorexia nervosa and in binge-eating disorder, but not in bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 Jun;30(6):1216–1221. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]