Abstract

Background

A large amount of inter-individual variability exists in the occurrence of symptoms in patients on chemotherapy (CTX). The purposes of this study, in a sample of oncology outpatients who were receiving CTX (n=582), were to identify subgroups of patients based on their distinct experiences with 25 commonly occurring symptoms and to identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with subgroup membership. In addition, differences in QOL outcomes were evaluated.

Methods

Oncology outpatients with breast, gastrointestinal, gynecological, or lung cancer completed the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale prior to their next cycle of CTX. Latent class analysis was used to identify subgroups of patients with distinct symptom experiences.

Results

Three distinct subgroups of patients were identified (i.e., 36.1% in Low class; 50.0% in Moderate class, 13.9% in All High class). Patients in the All High class were significantly younger, more likely to be female and Non-white, had lower levels of social support, lower socioeconomic status, poorer functional status, and a higher level of comorbidity.

Conclusions

Findings from this study support the clinical observation that some oncology patients experience a differentially higher symptom burden during CTX. These high risk patients experience significant decrements in QOL.

INTRODUCTION

Patients receiving chemotherapy (CTX) experience multiple co-occurring symptoms. On average, these patients report ten unrelieved symptoms that have a negative impact on their functional status and quality of life (QOL).1 However, a large amount of inter-individual variability exists with some patients experiencing a few symptoms while others experience every symptom associated with a given CTX regimen. The demographic and clinical characteristics that contribute to this inter-individual variability in patients’ symptom experiences warrant investigation so that high risk patients can be identified and pre-emptive symptom management interventions can be initiated.

Previous work from our research team focused on the identification of these high risk patients based on an evaluation of their experiences with the four most common symptoms associated with cancer and its treatment (i.e., pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression).2–6 Across five separate studies, using either cluster analysis or latent class analysis (LCA), three to five distinct subgroups of patients were identified. Of note, across all five studies, one subgroup of patients was characterized as having low levels of all four symptoms and another subgroup was characterized as having high levels of all four symptoms. In these studies, compared to patients with low levels of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression, patients in the “All High” subgroup were significantly younger and reported lower functional status and decreased QOL.2–6 In the two studies that evaluated for differences in clinical characteristics among the patient subgroups,2,6 no differences were identified.

In another group of studies,7,8 that used symptom occurrence ratings from the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS)9 to identify high risk patients, only two distinct subgroups were identified, namely patients with low and high symptom occurrence rates. Again, in both of these studies, while clinical characteristics were not associated with subgroup membership, patients in the high symptom subgroup reported decrements in functional status and QOL. The reason for the inconsistent number of subgroups identified across these seven studies2–8 may relate to the number of symptoms evaluated; whether symptom occurrence or severity ratings were used to create the patient subgroups; the statistical procedures used to identify the subgroups; as well as the relatively small sample sizes.

In the era of precision medicine,10 the specialty of oncology has led efforts to identify distinct tumor subtypes for several cancers (e.g., breast cancer,11,12 lung cancer13) based on tumor-specific characteristics and molecular profiles. The goal of these efforts is to develop mechanistically-based cancer treatments.14 Despite some limitations, the emerging evidence cited above suggests that similar studies need to be done to identify distinct subgroups of patients who will require more targeted symptom management interventions while undergoing cancer treatment.2–8 The purposes of this study, in a sample of oncology outpatients who were receiving CTX (n=582), were to identify subgroups of patients based on their distinct experiences with 25 commonly occurring symptoms and to identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with subgroup membership. In addition, differences in QOL outcomes were evaluated.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Settings

This study is part of an ongoing, longitudinal study of the symptom experience of oncology outpatients receiving CTX. Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, gastrointestinal, gynecological, or lung cancer; had received CTX within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of CTX; were able to read, write, and understand English; and gave written informed consent. Patients were recruited from two Comprehensive Cancer Centers, one Veteran’s Affairs hospital, and four community-based oncology programs. A total of 969 patients were approached and 582 consented to participate (60.1% response rate). The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment.

Instruments

A demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangements, education, employment status, and income. Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale15 was used to evaluate patients’ functional status. Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ)16 evaluated the occurrence, treatment, and functional impact of comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, arthritis).

The MSAS was used to evaluate the occurrence, severity, frequency, and distress of 32 symptoms commonly associated with cancer and its treatment. The MSAS is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure the multidimensional experience of symptoms. Patients were asked to indicate whether or not they had experienced each symptom in the past week (i.e., symptom occurrence). If they had experienced the symptom, they were asked to rate its frequency of occurrence, severity, and distress. The reliability and validity of the MSAS is well established in studies of oncology inpatients and outpatients.9,17

Quality of life was evaluated using generic (i.e., Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form-12 (SF-12))18 and disease-specific (i.e., Quality of Life Scale-Patient Version (QOL-PV)) measures.19–21 Both measures have well-established validity and reliability. Higher scores on both measures indicate a better QOL.

Study Procedures

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites. Eligible patients were approached by a research staff member in the infusion unit to discuss participation in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Depending on the length of their CTX cycles, patients completed questionnaires in their homes, a total of six times over two cycles of CTX (i.e., prior to CTX administration (i.e., recovery from previous CTX cycle), approximately 1 week after CTX administration (i.e., acute symptoms), approximately 2 weeks after CTX administration (i.e., potential nadir)). For this analysis, symptom occurrence data from the enrollment assessment that asked patients to report on their symptom experience for the week prior to the administration of the next cycle of CTX, were analyzed (i.e., recovery from previous CTX cycle). Medical records were reviewed for disease and treatment information.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics.

LCA was used to identify subgroups of patients (i.e., latent classes) with similar symptom experiences.22,23 While the MSAS evaluates the occurrence, severity, and distress associated with 32 symptoms, for this analysis and consistent with previous studies,7,8 the LCA was performed based on patients’ ratings of symptom occurrence. Since this analysis was somewhat exploratory, only data from the enrollment assessment was used in the LCA.

LCA identifies latent classes based on an observed response pattern.24,25 In order to have a sufficient number of patients with each symptom to perform the LCA, the MSAS symptoms that occurred in ≥40% of the patients were used to identify the distinct latent classes. A total of 25 out of 32 symptoms from the MSAS occurred in ≥40% of the patients.

The final number of latent classes was identified by evaluating the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and entropy. The model that fits the data best had the lowest BIC.26 In addition, well-fitting models produce entropy values of ≥.80.27 Finally, well-fitting models “make sense” conceptually and the estimated classes differ as might be expected on variables not used in the generation of the model.26

The LCA was performed using Mplus™ Version 7.28,29 Estimation was carried out with robust Maximum-Likelihood (MLR) and the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm.22 Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics and QOL outcomes, among the latent classes, were evaluated using analyses of variance, Kruskal-Wallis, and Chi Square analyses. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. As was done in our previous studies,5,30–32 based on the recommendations of Rothman33 and the large sample size, adjustments were not made for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Latent Class Analysis

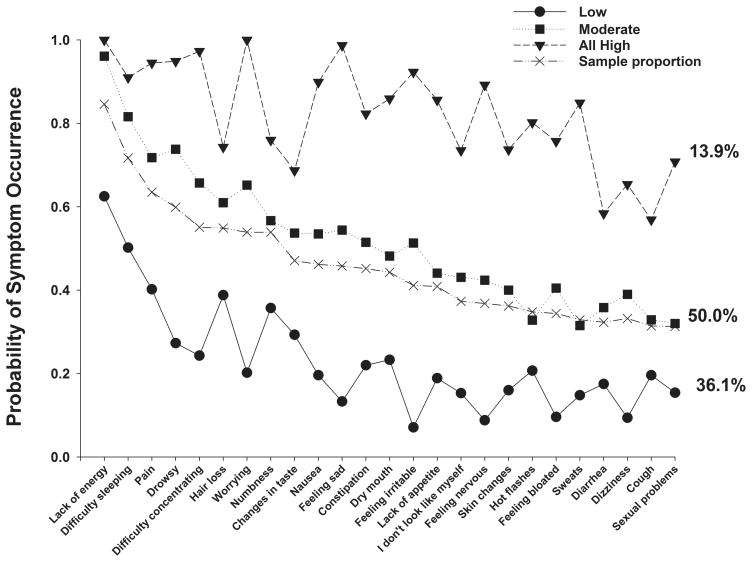

A total of 25 symptoms from the MSAS occurred in ≥40% of the patients (Figure 1) Using LCA, three distinct latent classes of patients were identified based on their ratings of the occurrence of these 25 MSAS symptoms. Fit indices for the candidate models are shown in Table 1. The three class solution was selected because its BIC was lower than the BIC for both the 2- and 4-class solutions. As summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 1, the largest percentage of patients (50.0%, n=291) was classified in the “Moderate” class. Probability of occurrence for most of the MSAS symptoms for this class was between 0.4 and 0.6. A second group, that comprised 13.9% (n=81) of the patients, was classified as the “All High” class. Probability of occurrence for most of the MSAS symptoms for this class was between 0.7 and 1.0. The third class, comprised of 36.1% (n=210) of the sample, was classified as the “Low” class. Probability of occurrence for most of the MSAS symptoms for this class was between 0.1 and 0.4.

Figure 1.

Probability of symptom occurrence for the total sample (i.e., sample proportion) and each of the latent classes for the 25 symptoms on the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale that occurred in ≥40% of the total sample (n=582).

Table 1.

Latent Class Solutions and Fit Indices for Two- Through Four-Class Solutions

| Model | LL | AIC | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Class | −8592.30 | 17286.59 | 17509.28 | .83 |

| 3 Classa | −8404.48 | 16962.96 | 17299.17 | .85 |

| 4 Class | −8329.83 | 16865.66 | 17315.40 | .87 |

The three class solution was selected because the BIC for that solution was lower than the BIC for both the 2- and 4-class solutions.

Note. LL = log-likelihood; AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion

Differences in Patient Characteristics Among the Latent Classes

Table 2 summarizes the differences in demographic and clinical characteristics among the latent classes. Compared to the Low class, patients in the Moderate and All High classes were more likely to be female, significantly younger, reported a lower KPS score, and had a higher comorbidity score. With the exception of the KPS and comorbidity scores, none of the clinical characteristics (i.e., time since diagnosis, cancer diagnosis, types and number of prior treatments, reason for current therapy, presence or number of metastatic sites) differed among the latent classes. Patients in the All High class reported the occurrence of a significantly higher number of symptoms (20.3 ± 2.7) than patients in the Moderate class (12.9 ± 2.6). Patients in the Moderate class reported a significantly higher number of symptoms than patients in the Low class (5.7 ± 2.3).

Table 2.

Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Among the Latent Classes (n=582)

| Characteristic | Low (1) n=210 36.1% |

Moderate (2) n=291 50.0% |

All High (3) n=81 13.9% |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 59.5 (11.4) | 56.5 (12.2) | 54.7 (11.2) | F=6.07, p=.002 1> 2 and 3 |

|

| ||||

| Education (years) | 16.5 (3.0) | 16.5 (3.0) | 15.4 (2.5) | F=5.00, p=.007 1 and 2 > 3 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.0 (5.6) | 26.5 (6.2) | 26.9 (5.3) | F=0.88, p=.417 |

|

| ||||

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 85.5 (10.3) | 79.2 (11.6) | 72.6 (11.8) | F=38.73, p<.0001 1>2>3 |

|

| ||||

| Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire score | 5.2 (3.0) | 6.7 (3.5) | 9.2 (4.6) | F=38.99, p<.0001 1<2<3 |

|

| ||||

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 2.1 (3.4) | 2.8 (4.9) | 2.4 (4.7) | F=1.33, p=.266 |

|

| ||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | 1.8 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.5) | F=1.71, p=.311 |

|

| ||||

| Number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvementa | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.2) | F=1.00, p=.370 |

|

| ||||

| Number of metastatic sites excluding lymph node involvement | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.0) | F=1.89, p=.152 |

|

| ||||

| Mean number of MSAS symptoms (out of 25) | 5.7 (2.3) | 12.9 (2.6) | 20.3 (2.7) | F=1106.36, p<.0001 1<2<3 |

|

| ||||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

|

| ||||

| Gender (% female) | 69.5 (146) | 83.5 (243) | 92.6 (75) | χ2=24.39, p<.0001 1<2 and 3 |

|

| ||||

| Self-reported ethnicity | χ2=8.81, p=.012 1 and 2 >3 |

|||

| White | 75.4 (156) | 74.8 (211) | 59.0 (46) | |

| Non-white | 24.6 (51) | 25.2 (71) | 41.0 (28) | |

|

| ||||

| Married or partnered (% yes) | 74.5 (155) | 65.6 (189) | 55.0 (44) | χ2=10.80, p=.005 1>3 |

|

| ||||

| Lives alone (% yes) | 16.0 (33) | 22.6 (65) | 22.2 (18) | χ2=3.45, p=.179 |

|

| ||||

| Currently employed (% yes) | 39.0 (82) | 34.6 (100) | 23.8 (19) | χ2=5.99, p=.050 |

|

| ||||

| Annual household income | KW=22.81, p<.0001 1 and 2 > 3 |

|||

| Less than $30,000 | 15.8 (29) | 15.2 (40) | 40.5 (30) | |

| $30,000 to $70,000 | 16.9 (31) | 22.7 (60) | 14.9 (11) | |

| $70,000 to $100,000 | 16.9 (31) | 15.2 (40) | 21.6 (16) | |

| Greater than $100,000 | 50.3 (92) | 47.0 (124) | 23.0 (17) | |

|

| ||||

| Child care responsibilities (% yes) | 18.5 (38) | 23.9 (68) | 31.2 (25) | χ2=5.52, p=.063 |

|

| ||||

| Elder care responsibilities (% yes) | 5.2 (10) | 11.7 (31) | 6.6 (5) | χ2=6.56, p=.038 1<2 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer diagnosis | χ2=11.17, p=.083 | |||

| Breast cancer | 38.6 (81) | 42.3 (123) | 54.3 (44) | |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 32.4 (68) | 25.4 (74) | 17.3 (14) | |

| Gynecological cancer | 18.1 (38) | 21.6 (63) | 22.2 (18) | |

| Lung cancer | 11.0 (23) | 10.7 (31) | 6.2 (5) | |

|

| ||||

| Prior cancer treatment | χ2=9.56, p=.144 | |||

| No prior treatment | 23.2 (48) | 15.3 (44) | 12.3 (10) | |

| Only surgery, CTX, or RT | 35.7 (74) | 44.3 (127) | 44.4 (36) | |

| Surgery and CTX, or surgery and RT, or CTX and RT | 25.1 (52) | 22.0 (63) | 22.2 (18) | |

| Surgery and CTX and RT | 15.9 (33) | 18.5 (53) | 21.0 (17) | |

|

| ||||

| Reason for current treatment | χ2=2.678, p=..261 | |||

| Curative intent | 76.1 (159) | 70.6 (202) | 77.8 (63) | |

| Noncurative intent | 23.9 (50) | 29.4 (84) | 22.2 (18) | |

|

| ||||

| Metastatic sites | χ2=3.94, p=.685 | |||

| No metastasis | 31.1 (65) | 31.7 (92) | 37.5 (30) | |

| Only lymph node metastasis | 22.0 (46) | 19.3 (56) | 21.2 (17) | |

| Only metastatic disease in other sites | 21.5 (45) | 24.5 (71) | 15.0 (12) | |

| Metastatic disease in lymph nodes and other sites | 25.4 (53) | 24.5 (71) | 26.2 (21) | |

Total number of metastatic sites evaluated was 9.

Abbreviations: CTX = chemotherapy, kg = kilograms, KW = Kruskal Wallis, m2 = meters squared, RT = radiation therapy, SD = standard deviation

Differences in Quality of Life Scores Among the Latent Classes

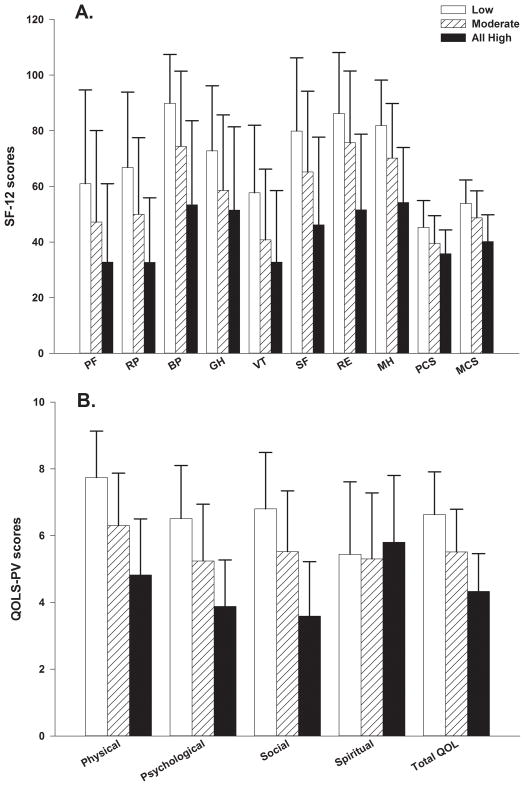

As shown in Figure 2A, for all of the scales on the SF12 as well as the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores, patients in the All High class reported significantly lower scores compared to patients in the Moderate class. Except for the General Health score on the SF12, patients in the Moderate class reported significantly lower scores than patients in the Low class.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A – Differences among the latent classes in the subscale and summary scores for the Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form 12 (SF-12). All values are plotted as means ± standard deviations. Significant differences: For PF: Low>Moderate (p<.0001) >All High (p=.002). For RP, BP, SF, RE, MH, and MCS: Low>Moderate>All High (both p<.0001). For GH: Low>Moderate and All High (p<.0001). For VT: Low>Moderate (p<.0001) >All High (p=.037). For PCS: Low>Moderate (p<.0001) > All High (p=.006).

Abbreviations: PF=physical functioning, RP=role physical, BP=bodily pain, GH=general health, VT=vitality, SF=social functioning, RE=role emotional, MH=mental health, PCS=physical component summary, MCS=mental component summary.

Figure 2B - Differences among the latent classes in the subscale and total quality of life (QOL) scores for the Quality of Life Scale-Patient Version (QOL-PV). All values are plotted as means ± standard deviations. Significant differences: Physical, Psychological, and Social Functioning subscales and total QOL scores: Low>Moderate>All High (both p<.0001).

As shown in Figure 2B, except for the spiritual well-being subscale, patients in the All High class reported significantly lower scores on the QOL-PV subscale and total scores than patients in the Moderate class. Patients in the Moderate class reported significantly lower QOL-PV scores than patients in the Low class.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use LCA to identify three distinct subgroups of patients based on their reports of the occurrence of 25 common symptoms prior to their next cycle of CTX. Consistent with our previous studies,2,5,6 approximately 14% of the patients reported relatively high occurrence rates for all 25 symptoms. The mean number of symptoms reported by the All High class (i.e., 20.3) is higher than the mean of 10 symptoms reported in cross-sectional studies that did not use specific analytic techniques to identify inter-individual variability in patients’ symptom experiences.1 Equally important, patients in the Low class reported an average of 6 symptoms which constitutes a fairly high symptom burden. Findings from this study suggest that rather than simply reporting the mean number of symptoms, future studies should employ the types of statistical approaches used in this and other studies,2,5–8 to be able to identify oncology patients at higher risk for increased symptom burden. The reliance on mean values for total number of symptoms will over- and under- estimate symptom burden and not allow for the identification of patients who require more intensive symptom management interventions.

While none of the clinical characteristics, except KPS and comborbidity, was associated with class membership, a number of demographic characteristics differentiated among the three latent classes. Consistent with previous reports,5,34,35 younger patients were more likely to be in the All High class. Several potential explanations may account for this finding. Older patients may receive lower doses of CTX;36,37 age-related changes may occur in the hypothalamic-adrenal-pituitary axis that mediate the occurrence of cancer-related symptoms;38 or older patients may experience a “response shift” in their perception of symptoms.39,40 Other characteristics that differentiated among the classes were gender and ethnicity with a higher percentage of women and non-Whites being in the All High class. Additional research is warranted because findings regarding gender41–45 and ethnic46,47 differences in the occurrence and severity of symptoms in oncology patients are inconsistent.

Equally important, several socioeconomic characteristics were associated with a higher symptom burden. The finding that marital status distinguished among the three latent classes may be related to perceived levels of social support. In several studies, oncology patients who reported higher levels of social support reported lower levels of depressive symptoms.48–50 While social support was not measured in this study, this hypothesis is supported by the finding that patients in the Moderate and All High classes reported significantly lower social functioning scores on both the generic and disease specific measures of QOL. Consistent with previous reports,51–53 patients in the All High class were more likely to report a lower annual household income. The reason for this disparity warrants investigation in future studies.

Of note, for both the generic and disease-specific measures of QOL, patients in the All High class reported worse QOL outcomes than patients in the Low and Moderate classes. Compared to the Low class, decrements in functional status reported by the Moderate (d = 0.5) and All High (d = 1.1) classes, represent not only statistically significant, but clinically meaningful differences in KPS scores.54,55 The effect size indicator (i.e., d) equals the difference between the two group means in standard deviation units. Similar effect sizes were found for the various subscales of both the generic and disease-specific QOL measures. In terms of the SF-12 PCS scores, all three classes had scores below the United States population mean score of 50. The effect size calculations for differences between the Low and Moderate, as well as the Low and All High classes, in PCS scores were d=0.6 and d=1.0, respectively.

For the SF-12 MCS scores, the Moderate and All High classes had scores below national norms. The effect size calculations for the MCS scores indicated clinically meaningful differences between the Low and Moderate (d=0.5) as well as the Low and High (d=1.3) classes. Finally, the effect size calculations for the total score on the disease-specific measure of QOL (i.e., QOL-PV19–21) identified clinically meaningful differences when the Low class was compared to the Moderate (d=0.9) and All High (d=1.6) classes. Taken together and consistent with previous reports,2,5–8 these findings emphasize the significant impact that the co-occurrence of multiple symptoms has on patients’ ability to function and their QOL.

While consistent with previous reports,2–4,6–8 a surprising finding from this study is that except for the decrements in functional status and severity of comorbidities, none of the disease and treatment characteristics were associated with class membership. The relatively small and heterogeneous samples in terms of cancer treatment, may explain the lack of associations between disease and treatment characteristics in previous studies. However, in the current study, the large sample size, as well as the relatively even distribution of cancer diagnoses, reasons for CTX treatment, and extent of metastatic disease across the three latent classes suggests that alternative explanations are plausible. One potential explanation for the lack of disease and treatment effects is that patients with a higher disease burden and more severe symptoms declined study participation. Another explanation for the lack of disease and treatment effects is that inter-individual variability in patients’ symptom experiences may be associated with genetic and epigenetic determinants. This hypothesis is supported by work from our research team and others on the association between a number of candidate genes and individual symptoms (e.g., pain,32,56,57 fatigue,58–63 depression,30,64,65 sleep disturbance31) in oncology patients. Studies are underway in our laboratory to identify specific biomarkers associated with membership in the All High class identified in this study.

Several study limitations need to be acknowledged. Patients were recruited at various points in their CTX treatments. In addition, the types of chemotherapy were not homogeneous. While we cannot rule out the potential contributions of clinical characteristics to patients’ symptom experiences, the relatively similar proportions of cancer diagnoses, reasons for current treatment, time since diagnosis, and evidence of metastatic disease suggest that the classes were relatively similar in terms of disease and treatment characteristics. While it is possible that patients in the Low class were receiving more aggressive symptom management interventions, the occurrence rates for the four most common symptoms (i.e., lack of energy, difficulty sleeping, pain, feeling drowsy, difficulty concentrating) were relatively proportional across the three classes. The study used symptom occurrence rates in the LCA and did not evaluate for changes over time in latent class membership. It is possible that using ratings of severity or distress to create the latent classes would provide additional information on inter-individual differences in the symptom experience of these patients.

In conclusion, findings from this study support the clinical observation that some oncology patients experience a differentially higher symptom burden during CTX. Risk factors identified in this study include: younger age, being female, being Non-white, lower levels of social support, lower socioeconomic status, poorer functional status, and a higher level of comorbidity. These high risk patients experience significant decrements in QOL. Future studies will focus on the identification of molecular mechanisms that contribute to this high risk phenotype, as well as the identification of latent classes using patients’ ratings of symptom severity and distress.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (CA134900).

References

- 1.Esther Kim JE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE, Jahan T, Miaskowski C. A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:715–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pud D, Ben Ami S, Cooper BA, et al. The symptom experience of oncology outpatients has a different impact on quality-of-life outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodd MJ, Cho MH, Cooper BA, et al. Identification of latent classes in patients who are receiving biotherapy based on symptom experience and its effect on functional status and quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:33–42. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodd MJ, Cho MH, Cooper BA, Miaskowski C. The effect of symptom clusters on functional status and quality of life in women with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illi J, Miaskowski C, Cooper B, et al. Association between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression. Cytokine. 2012;58:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Paul SM, et al. Subgroups of patients with cancer with different symptom experiences and quality-of-life outcomes: a cluster analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:E79–89. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.E79-E89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira KA, Kimura M, Teixeira MJ, et al. Impact of cancer-related symptom synergisms on health-related quality of life and performance status. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwede CK, Small BJ, Munster PN, Andrykowski MA, Jacobsen PB. Exploring the differential experience of breast cancer treatment-related symptoms: a cluster analytic approach. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:925–933. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0364-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Research Council. Toward Precision Medicine: Building a Knowledge Network for Biomedical Research and a New Taxonomy of Disease. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anders CK, Zagar TM, Carey LA. The management of early-stage and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam SW, Jimenez CR, Boven E. Breast cancer classification by proteomic technologies: Current state of knowledge. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Y, He J. Molecular classification of non-small-cell lung cancer: diagnosis, individualized treatment, and prognosis. Front Med. 2013;7:157–171. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. How many molecular subtypes? Implications of the unique tumor principle in personalized medicine. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12:621–628. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karnofsky D, Abelmann WH, Craver LV, Burchenal JH. The use of nitrogen mustard in the palliative treatment of cancer. Cancer. 1948:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:183–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00435383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrell BR, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padilla GV, Grant MM. Quality of life as a cancer nursing outcome variable. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1985;8:45–60. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padilla GV, Presant C, Grant MM, Metter G, Lipsett J, Heide F. Quality of life index for patients with cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1983;6:117–126. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthen B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermunt JK, Magdison J. Latent class cluster analyses. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: with applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Science. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Graham S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: what does latent class analysis say? Child Development. 2007;78:1706–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus (Version 7) Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn LB, Aouizerat BE, Langford DJ, et al. Cytokine gene variation is associated with depressive symptom trajectories in oncology patients and family caregivers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Dhruva A, et al. Evidence of associations between cytokine genes and subjective reports of sleep disturbance in oncology patients and their family caregivers. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCann B, Miaskowski C, Koetters T, et al. Associations between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and breast pain in women prior to breast cancer surgery. J Pain. 2012;13:425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.02.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cataldo JK, Paul S, Cooper B, et al. Differences in the symptom experience of older versus younger oncology outpatients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritchie C, Dunn LB, Paul SM, et al. Differences in the Symptom Experience of Older Oncology Outpatients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsley C, Pond GR, Peloza B, et al. Analysis of treatment practices for elderly cancer patients in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3802–3810. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar A, Soares HP, Balducci L, Djulbegovic B National Cancer I. Treatment tolerance and efficacy in geriatric oncology: a systematic review of phase III randomized trials conducted by five National Cancer Institute-sponsored cooperative groups. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1272–1276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bower JE, Low CA, Moskowitz JT, Sepah S, Epel E. Benefit finding and physical health: positive psychological changes and enhanced allostasis. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2:223–244. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. The challenge of response shift for quality-of-life-based clinical oncology research. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:747–749. doi: 10.1023/a:1008305523548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz CE, Sprangers MA. Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:1531–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheung WY, Le LW, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C. Age and gender differences in symptom intensity and symptom clusters among patients with metastatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giesinger J, Kemmler G, Mueller V, et al. Are gender-associated differences in quality of life in colorectal cancer patients disease-specific? Qual Life Res. 2009;18:547–555. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinonen H, Volin L, Uutela A, Zevon M, Barrick C, Ruutu T. Gender-associated differences in the quality of life after allogeneic BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:503–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miaskowski C. Gender differences in pain, fatigue, and depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:139–143. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu OS, Crew KD, Jacobson JS, et al. Ethnicity and persistent symptom burden in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:241–250. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hann D, Baker F, Denniston M, et al. The influence of social support on depressive symptoms in cancer patients: age and gender differences. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Predictors of depressive symptomatology of geriatric patients with lung cancer-a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 2002;11:12–22. doi: 10.1002/pon.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simpson JS, Carlson LE, Beck CA, Patten S. Effects of a brief intervention on social support and psychiatric morbidity in breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2002;11:282–294. doi: 10.1002/pon.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akin S, Can G, Aydiner A, Ozdilli K, Durna Z. Quality of life, symptom experience and distress of lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:250–256. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarna L. Correlates of symptom distress in women with lung cancer. Cancer Practice. 1993;1:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:371–383. doi: 10.4065/77.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osoba D. Interpreting the meaningfulness of changes in health-related quality of life scores: lessons from studies in adults. International Journal of Cancer Supplement. 1999;12:132–137. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<132::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reyes-Gibby CC, Shete S, Yennurajalingam S, et al. Genetic and nongenetic covariates of pain severity in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: assessing the influence of cytokine genes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:894–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reyes-Gibby CC, El Osta B, Spitz MR, et al. The influence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha -308 G/A and IL-6 -174 G/C on pain and analgesia response in lung cancer patients receiving supportive care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3262–3267. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Felger JC, Cole SW, Pace TW, et al. Molecular signatures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells during chronic interferon-alpha treatment: relationship with depression and fatigue. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1591–1603. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jim HS, Park JY, Permuth-Wey J, et al. Genetic predictors of fatigue in prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy: preliminary findings. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reinertsen KV, Grenaker Alnaes GI, Landmark-Hoyvik H, et al. Fatigued breast cancer survivors and gene polymorphisms in the inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Cole SW. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: early findings. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1197–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K, et al. Preliminary evidence of an association between a functional interleukin-6 polymorphism and fatigue and sleep disturbance in oncology patients and their family caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aouizerat BE, Dodd M, Lee K, et al. Preliminary evidence of a genetic association between tumor necrosis factor alpha and the severity of sleep disturbance and morning fatigue. Biol Res Nurs. 2009;11:27–41. doi: 10.1177/1099800409333871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JM, Kim SW, Stewart R, et al. Serotonergic and BDNF genes associated with depression 1 week and 1 year after mastectomy for breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:8–15. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318241530c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schillani G, Martinis E, Capozzo MA, et al. Psychological response to cancer: role of 5-HTTLPR genetic polymorphism of serotonin transporter. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:3823–3826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]