Summary

Patterns of neural activity are critical for sculpting the immature brain and disrupting this activity is believed to underlie neurodevelopmental disorders [1-3]. Neural circuits undergo extensive activity-dependent postnatal structural and functional changes [4-6]. The different forms of neural plasticity [7-9] underlying these changes have been linked to specific patterns of spatiotemporal activity. Since maternal behavior is the mammalian infant's major source of sensory driven environmental stimulation and the quality of this care can dramatically impact neurobehavioral development [10], we explored, for the first time, whether the infant cortical activity was influenced directly by interactions with the mother within natural nest environment. We recorded spontaneous neocortical local field potentials (LFP) in freely behaving infant rats, from postnatal days ~12-19 during natural interactions with their mother. We show that maternal absence from the nest increased cortical desynchrony. Further isolating the pup by removing littermates induced further desynchronization. The mother's return to the nest reduced this desynchrony, and nipple attachment induced a further reduction but increased slow-wave activity. However maternal simulation of pups (grooming, milk-ejection) consistently produced rapid, transient cortical desynchrony. The magnitude of these maternal effects decreased with age. Finally, systemic blockade of noradrenergic beta receptors led to reduced maternal regulation of infant cortical activity. Our results demonstrate that during early development, mother-infant interactions can immediately impact infant brain activity, in part via a noradrenergic mechanism, suggesting a powerful influence of the maternal behavior and presence on circuit development.

Results and Discussion

Here we examined the impact that maternal behavior and interactions between mother and infant have on infant cortical brain activity. We specifically examined changes in infant cortical LFP activity induced by maternal behavior, including maternal presence or absence from the nest, as well as typical infant-mother interactions such as nipple attachment, milk ejections and maternal grooming behavior of pups. In Experiment 1, a total of 6 pups from 6 different litters were recorded daily between ages of postnatal (P) ~12-20. We examined the changes in LFP activity across maternal behavioral state collapsed by age, as well as across age, using a within-animal design. In Experiment 2, an additional 5 pups from 5 different litters were used to examine the impact of blocking norepinephrine (NE)-beta receptors on cortical activity, due to their role in neural development and maternal stimulation [11, 12]. For all data presented here, monopolar recordings were from somatosensory neocortex. An additional data set obtained from recordings within the amygdala is presented in the supplemental material (see Figure S1).

Maternal and littermate absence increases cortical desynchronization

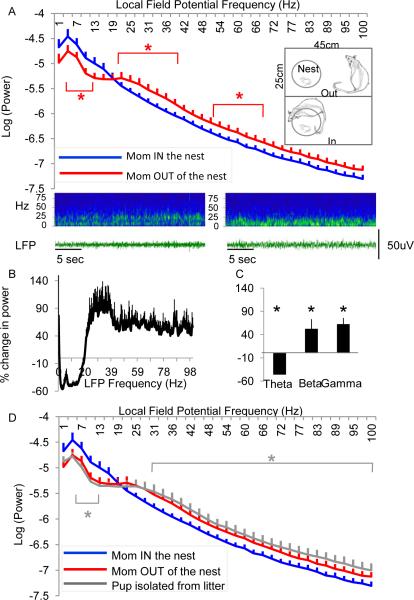

We first determined the immediate impact of the mother's presence or absence in the nest on her infants’ brain activity. In both instances, pups were typically in a huddle with littermates (Fig 1A, n = 6 pups). When the dam was away from the nest, yet still within the 34 × 29 × 17 cm cage, there was an increase in cortical desynchronization relative to when she was in the nest near the pups (Figure 1A, main effect of maternal presence: ANOVA: F(1, 208) = 78.5, p<0.0001). Post hoc comparisons across each frequency bin revealed significant increases within the beta and gamma frequency ranges (~24-72Hz, p<0.05, after applying a Bonferroni correction for repeated measures, specific frequencies marked by an asterisk). We determined that the absence of the mother induces a ~40-60% increase in LFP power within the beta and gamma frequency bands (Figure 1B, C). Analysis of mean power change within specific frequency bands revealed significant changes in theta (t(6) = 9.1, p < 0.0001; beta, t(6) =2.54, p<0.05 and gamma frequency bands, t(6) = 4.7, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Maternal absence increases cortical desynchrony. A. Average power (Log(power)) across LFP frequency (Hz) when the dam is in the nest (blue) versus out of the nest (red) for all animals collapsed across all days of recording. (Insets: Home cage with dam out (bottom) and in (top) the nest area, drawn to scale. Cage size: 45cm length × 25 cm height.) Below: Example sonogram (top) and LFP traces (bottom) taken from a single animal within the same session at time points while the dam was out of the nest (left) or in the nest (right). White dashed line is placed as a reference to compare activity across both behavioral states. B. Average percent change in power across all frequencies or averaged across frequency band (C) when dam is out of the nest compared to when dam is in the nest. Error bars = SEM, * = p<0.05. (D) Isolation from both maternal caregiver and littermates further increases cortical desynchrony. Average power (log(power)) across LFP frequency when the pup is isolated from both the dam and litter (gray) is compared to average power across LFP frequency when the dam is present (blue) or absent (red) from the nest. See also Figure S1. Error bars = SEM. * = p<0.05.

Placing the infant in an isolated environment, without the dam and littermates induced further desynchronization relative to within the nest (Figure 1D). A pup behavioral state X LFP frequency ANOVA again revealed a significant main effect of mother and littermate presence (Isolated pup vs. dam in the nest (n = 6): F(1,208)=57.7, p<0.0001), with post hoc tests confirming a specific significant difference within the beta and gamma frequency bands (~33-100Hz). These changes were not due to pups’ sleep-wake cycle when the mom was present or absent, since pups could experience both sleep and arousal when the mother was in or out of the nest. Together these results uncover that the mere presence of the mother, as well as other littermates in the nest, provide an immediate impact on the state of cortical neural activity, with maternal/littermate absence inducing desynchonization.

Nursing behavior induces LFP synchrony while milk delivery induces desynchrony

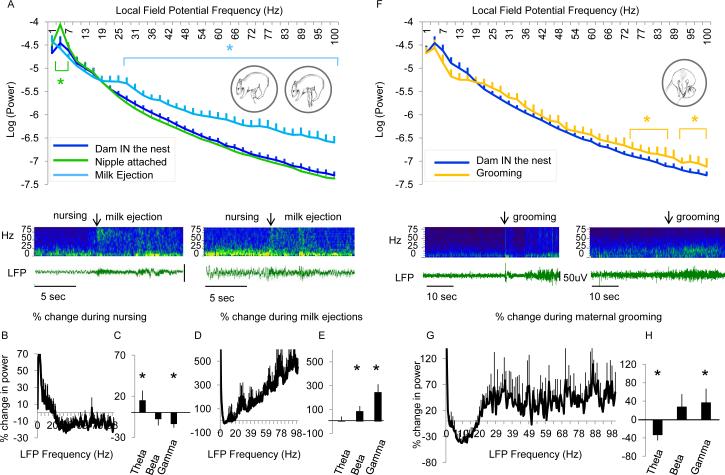

We then examined how brain state is influenced by attachment to the maternal nipple as well as during a milk ejection (Figure 2, inset images). Figure 2A shows that while the infant is attached to the nipple there was a small reduction of cortical desynchronization in the LFP signal. This reduction primarily occurred within the gamma frequency bands leading to about a 10-20% reduction of LFP power (Figure 2B-C) (Main effect of maternal behavior ANOVA (n = 6 pups): Nursing vs. Dam in the nest F (1, 208) = 34.6, p < 0.0001). Post hoc analyses reveal a significant increase in slow-wave activity (0-5Hz) (Figure 2A) (post hoc analyses: ~2-5Hz, p<0.05). Analysis of mean power change within specific frequency bands revealed significant changes in theta (t(6) = 2.2, p < 0.05) and gamma frequency bands (t(6) = 3.0, p < 0.05). This increase in slow-wave activity was associated with a decrease in high frequency activity and often linked to slow wave sleep [13]. Nursing behavior was typically interspersed with periods of milk delivery, which is signaled by a robust stretch reflex in the pups, each lasting for about 10-15 seconds. Milk ejection induced a dramatic increase in high frequency oscillations, specifically across beta and gamma frequency bands (Figure 2A) and a behavioral state X LFP frequency ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition (Milk ejection vs. Dam in the nest) (n = 6 pups): F (1, 208) = 235.3, p < 0.0001). Post hoc tests showed specific increases in LFP power within the beta and gamma frequency band (~27-100Hz; p < 0.05) relative to the state of maternal presence. Analysis of mean power change within specific frequency bands revealed significant changes in beta (t(6) = 2.3, p < 0.05) and gamma frequency bands (t(6) = 3.7, p < 0.01). In fact, periods of milk ejections produced an increase of activity of 100-300% in the beta and gamma frequency bands relative to the pre-milk-ejection period (Figure 2D-E).

Figure 2.

Nursing behavior reduces cortical desynchrony while delivery of milk produces a surge of desynchrony. A. Average log(power) across LFP frequency (Hz) while the pup is attached to the dam's nipple (green) and receiving a milk ejection (light blue) compared to when the dam is in the nest (blue) for all animals collapsed across all days of recording (Insets: Nursing behavior with the pup nipple attached but not receiving milk (left) and when the infant receives a milk ejection (right).) Below: Example sonogram (top) and traces (bottom) taken from 2 animals during nursing behavior and receiving milk ejections (marked with an arrow). B. Average percent change in power across all frequencies or averaged across frequency band (C) when the pup is attached to dam's nipple. D. Average percent change in power across all frequencies or averaged across frequency band (E) when the pup is receiving a milk ejection. Error bars = SEM, * = p<0.05. F. Maternal grooming increases cortical desynchrony. Average log(power) across LFP frequency (Hz) when the pup is groomed by the dam (orange) versus when the dam is in the nest (blue) for all animals collapsed across all days of recording. (Inset: Grooming behavior by the mother.) Below: Example sonogram (top) and traces (bottom) taken from 2 animals during grooming behavior (marked with an arrow). G. Average percent change in power across all frequencies or averaged across frequency band (H) when dam is in the nest compared to when dam is grooming the pup. See also Figure S1. Error bars = SEM, * = p<0.05.

Maternal grooming increases cortical desynchronization

An additional major mother-pup interaction is grooming. This behavior induced a moderate increase of cortical desynchronization compared to when the dam was merely present in the nest (Figure 2F) maternal behavior X LFP frequency ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition (Grooming behavior vs. Dam in the nest (n = 6 pups): F (1, 208) = 24.1 p < 0.0001). Post hoc tests revealed that grooming behavior significantly enhanced LFP power within higher gamma frequency bands (~70-100Hz, p< 0.05). Analysis of mean power change within specific frequency bands revealed significant changes in theta (t(6) = 3.9, p < 0.01) and gamma frequency bands (t(6) = 2.4, p < 0.05). Figure 2G, H demonstrates an enhancement of LFP power between 20-40% compared to when the mother is in the nest but not grooming the target pup.

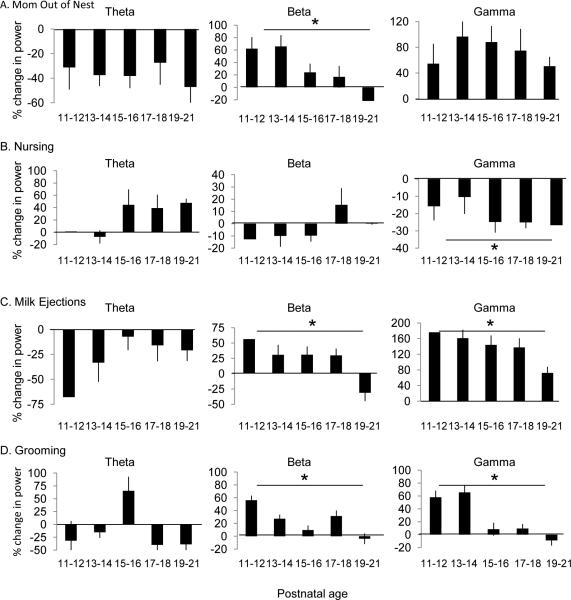

The impact of maternal presence and behavior decreases with age

We further examined whether the influence of mother-infant interactions on cortical LFP changed as pups approached the age of weaning (~P19-20). We assessed the differences in magnitude (% difference) of the response for each behavioral state as it compared to when the dam was in the nest (i.e., Milk delivery vs. Dam in the nest). Each behavioral state assessed is shown in Figure 3 (A. Dam out of the nest, B. Nursing, C. Milk delivery, D. Grooming). We found that the impact of maternal absence from the nest, milk delivery and grooming behavior on cortical activity decreased as pups approached weaning (i.e.: the differences between each state and the mother's presence in the nest declined with age). This was specifically seen for comparisons in the beta and gamma frequency ranges (Figure 3, right two columns; See Figure S2 for an assessment of baseline LFP as a function of age). For maternal presence in the nest, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of age for beta (F (1, 4) = 4.1, p < 0.05). For nursing behavior, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of age for gamma (F (1, 4) = 2.7, p < 0.05). For milk ejection, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of age for beta (F (1, 4) = 3.1, p < 0.05) and gamma (F (1, 4) = 3.6 p < 0.05). Finally, for grooming behavior, we found a significant main effect of age for beta (F (1, 4) = 2.8, p < 0.05) and gamma (F (1, 4) = 3.4, p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Impact of maternal presence and behavior decreases with age. Average percent change in power of LFP frequency band (theta (left), beta (middle), gamma (right)) across postnatal age when the dam is out of the nest (A), when nursing the pup (B), when giving a milk ejection (C) and when grooming the pup (D). Each bar represents percent change in LFP power when indicated behavior is compared to when the dam is in the nest. See also Figure S2. Error bars = SEM, * = p<0.05.

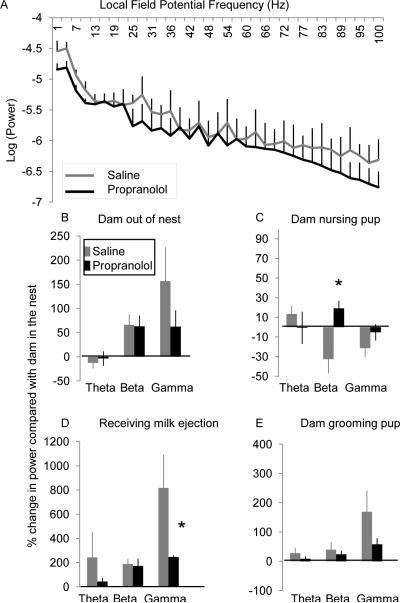

Impact of maternal presence and behavior involves a noradrenergic mechanism

Finally, we tested the hypothesis that the infant noradrenergic system is a potential mechanism contributing to the maternal behavior-induced changes in pup neural activity (n=5 pups). The noradrenergic locus coeruleus is functional early in development [14], and norepinephrine release induces cortical desynchrony during arousal [15]. The infant rodent locus coeruleus is uniquely responsive to sensory inputs, responding to a larger array of stimuli with more prolonged NE release than in adults, due to late inhibitory alpha-2 autoreceptor development [16, 17]. Microdialysis in rat pups demonstrates that stimuli mimicking maternal behaviors, such as grooming, enhance forebrain norepinephrine [18] and these stimuli support infant neural plasticity [11, 17].

We systemically blocked noradrenergic beta-receptors (propranolol, 20mg/kg) at least 30 min prior to a typical 1 hour recording session and compared the behavioral state-induced changes to neural activity during one session with propranolol and a control session after saline injection (the order of injections was alternated between animals). Following propranolol injection, neural activity during an isolated recording session (away from dam and littermates) decreased modestly within the beta and gamma frequency bands (Figure 4A). Statistical analysis revealed no main effect of drug on baseline LFP measurement when compared to a saline injection (Injection X LFP frequency ANOVA (Propranolol vs. Saline): F (1, 173= 2.57, p = 0.11).

Figure 4.

Impact of maternal presence and behavior involves a noradrenergic mechanism. A. Average log(power) across LFP frequency (Hz) during an isolated baseline recording following systemic saline injection (gray) and propranolol (black). There was no significant effect of propranolol on the basal spontaneous LFP. B-E: Average percent change in LFP power across frequency bands during behavioral interactions with the maternal caregiver following systemic propranolol injection (black) compared to systemic saline injection (gray). B: Maternal absence from the nest. C: Nursing behavior. D: Milk ejections. E: Grooming behavior. Error bars = SEM. * =p<0.05.

Effects of maternal behavior on infant neural activity were then assessed within a single session (propranolol or saline session) and the magnitude of maternal behavior induced changes in neural activity was compared between conditions (propranolol vs. saline). The magnitude of maternal behavior-induced changes in pup cortical activity was significantly reduced by propranolol. For example, the cortical desynchronization normally induced during maternal absence was moderately reduced by propranolol compared to saline injected pups (Figure 4B). Similarly, the effect of nursing behavior on LFP activity was also reduced, demonstrating a significant difference from control sessions in the beta frequency band (ANOVA: F = 10.3, p < 0.05, df = 8) (Figure 4C). The impact of milk delivery on neural activity was also greatly reduced following propranolol, specifically in the gamma frequency band (Figure 4D, ANOVA: F = 4.5, p< 0.05, df = 8). Finally, the impact of grooming behavior on the modulation of cortical activity was also reduced following propranolol injection with the greatest effect in the gamma frequency band (Figure 4E, ANOVA: F = 3.1, p = 0.06, df = 8). These results suggest an involvement of the noradrenergic system in maternally induced changes to pup neural activity (Figure 4B-E).

Altricial newborn mammals receive nutrition, warmth and protection from their caregiver. The newborns also respond to the sensory cues provided by the mother, and this maternal sensory stimulation helps shape sensory system ontogeny [10]. However, in addition to these transient sensory evoked responses, the results of the research presented here demonstrate that, within the nest environment, maternal behaviors modulate infant cortical activity, in part via a noradrenergic mechanism. A variety of other mechanisms may be involved, which we are currently exploring. These maternal care induced changes in pup cortical activity are not dependent upon pups’ arousal level since sleep and arousal occurred with and without maternal presence (e.g., quiescent pups in the litter show different cortical activity depending on the mother's presence or absence). These brain state changes can last for seconds to many minutes, and reflect dramatic cortical desynchronization during periods of maternal absence, milk ejection and maternal grooming of the pup. Cortical desynchronization is an activity pattern conducive to neural plasticity [19, 20] and information transfer across brain regions [13, 21]. Moreover, higher frequency oscillations are thought to be important for developing thalamocortical or neocortical-hippocampal synapses, specifically for the organization of topographical functional units in cortical regions and the maturation of specific cell circuitry [22, 23]. In contrast, during maternal presence, and particularly during nipple attachment (in the absence of milk ejection), pups demonstrate elevated slow-wave activity [24, 25]. This activity emerges rapidly and is maintained throughout nipple attachment. This suggests that in addition to natural, endogenous mechanisms of sleep pressure and homeostasis described in adults [26], within the nest environment attachment to a maternal nipple can induce slow-wave activity in pre-weanling pups. Slow-wave activity has been demonstrated to be critically involved in memory consolidation and synaptic homeostasis [27, 28], even in children [29]. Thus, entry into periods of slow wave activity may enable the induction of synaptic plasticity or solidification of circuitry formed during the periods of enhanced high oscillatory activity [28]. Thus, the data provide for the first time a direct window into the effects of mother-infant interactions within the nest on pup neural function, and suggest a powerful postnatal mechanism of maternal modulation of brain development.

Selective spatiotemporal patterns of spontaneous or stimulus evoked activity induce modifications in many systems, including influencing the synthesis and release of neuromodulators and neurohormones (e.g., norepinephrine [NE]; [30]), growth factors (e.g., brain derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF]; [31]). The norepinephrine-dependent cortical activation during milk ejection and grooming is particularly interesting since these stimuli are important for pups learning and expressing attraction to the maternal odor [32-34] [35] This maternal odor learning is norepinephrine dependent [36, 37]. The present results suggest that not only do maternal stimuli promote associative conditioning of specific cues, but also more generally modulate brain activity and arousal, in part via a noradrenergic mechanism. The immature noradrenergic nucleus locus coeruleus is far more sensitive to a wide range of sensory stimuli, and more robustly responsive than in the adult [14]. This diminution in locus coeruleus response with age is due in part to the late emergence of auto-inhibitory alpha-2 receptors [38], and may contribute to the decrease in pup cortical responsiveness to maternal stimulation with the approach toward weaning.

The maternal stimuli modulating infant brain state are likely to be multi-sensory and include at least olfactory, tactile and thermal cues given the known developmental emergence of sensory system function in rats. The fact that some maternal cues (e.g., absence from nest, milk) evoke arousal and cortical desynchrony and others (e.g., nipple attachment) evoke a shift to slow-wave state is particularly intriguing, and ongoing work is attempting to isolate mechanisms of nipple attachment-associated slow-wave state induction. In human infants, nutritive sucking is known to evoke different autonomic responses than non-nutritive sucking, which could parallel the cortical results observed here [39].

Finally, given the dramatic effects of maternal behavior on infant brain state shown here, and the known role of neural activity on brain circuit development, the results suggest this may be a mechanism allowing variation in maternal care to create variability in brain development and behavioral outcome. The nature and duration of specific maternal behaviors, as well as the temporal patterning of interaction and absence could induce robust individual differences in arousal and consolidation, and general network maturation. Previous work in our lab and others has revealed that variations of maternal care [40, 41], maternal deprivation [42], and maternal abuse [43, 44] have long-lasting neurobehavioral consequences, enabling vulnerability to later-life psychiatric disorders. Whereas, immediate effects of poor maternal care result in a paradoxical attraction for the caretaker [10], long term consequences of poor maternal care include maladaptive behaviors such as reduced fear learning and depressive-like behavior, related to attenuated amygdala function, altered gene expression and dysregulation in neural networks underlying olfactory learning [37, 44, 45]. The maternal modulation of infant brain state described here may contribute to these effects.

Experimental Procedures

Please see Supplemental Experimental Procedures for a full description of the paradigm design, methodology, and analysis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The mother's presence reduces infant rat cortical desynchronization

Maternal behaviors (i.e., milk ejection, grooming) increase desynchronization

Maternal effects on infant cortical activity decline with age

Norepinephrine receptor blockade reduces impact of dam on infant cortical activity

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01-DC009910 and R01-MH091451 to RMS and DAW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Penn A, Shatz C. Brain waves and brain wiring: the role of endogenous and sensory-driven neural activity in development. Pediat. Res. 1999;45:447–458. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199904010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shatz C. Emergence of order in visual system development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:602–608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz L, Shatz C. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monk CS, Webb SJ, Nelson CA. Prenatal neurobiological development: molecular mechanisms and anatomical change. Develop. Neuropsych. 2001;19:211–236. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN1902_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tau GZ, Peterson BS. Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:147–168. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo L, O'Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Ann. Rev. of Neurosci. 2005;28:127–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson J, Wong D, Lynch G. Patterned stimulation at the theta frequency is optimal for the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1986;368:347–350. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman D. The spike-timing dependence of plasticity. Neuron. 2012;75:556–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jutras M, Buffalo E. Synchronous neural activity and memory formation. Curr Opin in Neurobiol. 2010;20:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landers M, Sullivan R. The development and neurobiology of infant attachment and fear. Dev Neurosci. 2012;34:101–114. doi: 10.1159/000336732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan R, Wilson D, Leon M. Norepinephrine and learning-induced plasticity in infant rat olfactory system. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3998–4006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03998.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura S, Sakaguchi T. Development and plasticity of the locus coeruleus: a review of recent physiological and pharmacological experimentation. Prog. Neurobiol. 1990;34:505–526. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90018-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buzsaki G. Rhythms of the brain. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura S, Kimura F, Sakaguchi T. Postnatal development of electrical activity in the locus ceruleus. J Neurophysiol. 1987;58:510–524. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berridge CW, Foote SL. Effects of locus coeruleus activation on electroencephalographic activity in neocortex and hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3135–3145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03135.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura S, Kimura F, Sakaguchi T. Postnatal development of electrical activity in the locus ceruleus. J Neurophysiol. 1987;58:510–524. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moriceau S, Sullivan R. Unique neural circuitry for neonatal olfactory learning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1182–1189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4578-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shionoya K, Moriceau S, Bradstock P, Sullivan RM. Maternal attenuation of hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus norepinephrine switches avoidance learning to preference learning in preweanling rat pups. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;52:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman DE. The spike-timing dependence of plasticity. Neuron. 2012;75:556–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jutras MJ, Buffalo EA. Synchronous neural activity and memory formation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engel AK, Fries P, Singer W. Dynamic predictions: oscillations and synchrony in top-down processing. Nature Rev. 2001;2:704–716. doi: 10.1038/35094565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minlebaev M, Colonnese M, Tsintsadze T, Sirota A, Khazipov R. Early γ oscillations synchronize developing thalamus and cortex. Science. 2011;334:226–229. doi: 10.1126/science.1210574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seki M, Kobayashi N, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y. Synchronized spike waves in immature dentate gyrus networks. Eur. J Neurosci. 2012;35:673–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.07995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz D. Alimentary sleep satiety in suckling rats. Physiol and Behavior. 1986;38:557–562. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shair H, Brake S, Hofer M. Suckling in the rat: evidence for patterned behavior during sleep. Behav. Neurosci. 1984;98:366–370. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tononi G. Slow wave homeostasis and synaptic plasticity. J Clin. Sleep Med. 2009;5:S16–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nature Rev. 2010;11:114–126. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilhelm I, Rose M, Imhof KI, Rasch B, Buchel C, Born J. The sleeping child outplays the adult's capacity to convert implicit into explicit knowledge. Nature. 2013;16:391–393. doi: 10.1038/nn.3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nestler EJ, Alreja M, Aghajanian GK. Molecular control of locus coeruleus neurotransmission. Biol. Psych. 1999;46:1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balkowiec A, Katz DM. Cellular mechanisms regulating activity-dependent release of native brain-derived neurotrophic factor from hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10399–10407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofer M, Shair H, Singh P. Evidence that maternal ventral skin substances promote suckling in infant rats. Physiol. Beh. 1976;17:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teicher M, Blass E. First suckling response of the newborn albino rat: the roles of olfaction and amniotic fluid. Science. 1977;198:635–636. doi: 10.1126/science.918660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriceau S, Roth T, Sullivan R. Rodent model of infant attachment learning and stress. Develop. Psychobiol. 2010;52:651–660. doi: 10.1002/dev.20482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smotherman W, Robinson S. Milk as the proximal mechanism for behavioral change in the newborn. Acta. Paediatr. Suppl. 1994;397:64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan RM, Wilson DA, Leon M. Norepinephrine and learning-induced plasticity in infant rat olfactory system. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3998–4006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03998.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriceau S, Raineki C, Holman J, Holman J, Sullivan R. Enduring neurobehavioral effects of early life trauma mediated through learning and corticosterone suppression. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009;3 doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.022.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura S, Sakaguchi T. Development and plasticity of the locus coeruleus: a review of recent physiological and pharmacological experimentation. Prog. Neurobiol. 1990;34:505–526. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90018-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lappi H, Valkonen-Korhonen M, Georgiadis S, Tarvainen MP, Tarkka IM, Karjalainen PA, Lehtonen J. Effects of nutritive and non-nutritive sucking on infant heart rate variability during the first 6 months of life. Infant Beh. Dev. 2007;30:546–556. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caldji C, Diorio J, Meaney M. Variations in maternal care in infancy regulate the development of stress reactivity. Biol. Psych. 2000;48:1164–1175. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meaney M. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huot R, Thrivikraman K, Meaney M, Plotsky P. Development of adult ethanol preference and anxiety as a consequence of neonatal maternal separation in Long Evans rats and reversal with antidepressant treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:366–373. doi: 10.1007/s002130100701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raineki C, Cortes MR, Belnoue L, Sullivan RM. Effects of early-life abuse differ across development: infant social behavior deficits are followed by adolescent depressive-like behaviors mediated by the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7758–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5843-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarro E, Sullivan R, Barr G. Unpredictable neonatal stress enhances adult anxiety and alters amygdala gene expression related to serotonin and GABA. Neurosci. 2013;258C:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sevelinges Y, Moriceau S, Holman P, Miner C, Muzney K, Gervais R, Mouly A, Sullivan R. Enduring effects of infant memories: infant odor-shock conditioning attenuates amygdala activity and adult fear conditioning. Biol Psych. 2007;62:1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.