Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this three-wave longitudinal study was twofold. First, prevalence data on alcohol characteristics (e.g., drinks per day, heavy episodic drinking [HED]) were provided for a community sample of middle-aged adults. Aggregate (or group) and individual levels of stability of these characteristics across a 10-year interval were a major focus. Second, an actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) was used to test husbands’ and wives’ mutual influences on each other’s alcohol use.

Method:

Prospective data were collected from the middle-aged parents of a cohort study that originally targeted adolescents. Three measurement occasions occurred at baseline, 5 years later, and an additional 5 years later. Data from 597 men and 847 women were used to derive prevalence data on alcohol use, and 489 intact marital dyads were used to test spouses’ interdependence on alcohol use and HED in the APIMs.

Results:

The majority of men and women reported alcohol use at each measurement occasion, and the average number of drinks per day was highly similar across time, as was the percentage reporting HED. There was substantial stability at the individual level in the amount of alcohol consumed and HED between waves of measurement. Marital partners had significant but modest effects on each other’s alcohol use. Wives had a somewhat greater influence on their husbands’ drinking than vice versa.

Conclusions:

The majority of middle-aged adults consumed alcohol at a low to moderate level. However, there is heterogeneity in alcohol use patterns, and a significant minority reported at-risk levels of alcohol use and HED.

Middle age is a developmental phase of the life span that is important to study for a number of reasons, including that it portends movement into late life with attendant concerns related to cognitive, physical, and emotional functioning and health (Lachman, 2004). As such, optimal functioning of individuals during this period of life becomes increasingly important from both a personal and a public health perspective. Alcohol involvement, such as the quantity and frequency of alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking (HED), has implications for the health and well-being of middle-aged adults both concurrently and prospectively. For example, consistent low to moderate alcohol consumption (relative to abstention) in middle-aged and older adults has been associated with better health outcomes (Chen and Hardy, 2009; Kaplan et al., 2012; Karlamangla et al., 2009; Lang et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2011; Powers and Young, 2008), whereas heavier use has been associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, cancer, gastrointestinal disorders (Roerecke and Rehm, 2012), cognitive impairment (Anttila et al., 2004), and poorer psychological functioning (Choi and DiNitto, 2011a, 2011b).

In this article, we focus on two aspects of alcohol involvement among middle-aged adults. First, because there have been a limited number of longitudinal studies on alcohol use in middle age, we provide epidemiologic findings both on aggregate-level trends (i.e., population/sample level changes for different age groupings) and individual- (or intra-individual) level stability of alcohol characteristics for three waves of assessment across a 10-year window. Second, we use a mutual influence, couples’ approach to examine the impact of husbands’ drinking on wives’ drinking, and vice versa, across the three waves of measurement.

Alcohol use in middle-aged adults

In general, with increasing age there is a slow but steady increase in the number of abstainers and a gradual decline in quantity of alcohol consumed, HED, and alcohol problems (Blazer and Wu, 2009; Brennan et al., 2011; Breslow and Smothers, 2004; Platt et al., 2010). Although there is agreement of a general decline in alcohol involvement with increasing age, findings have differed with respect to the levels of stability and change during middle adulthood. For example, Brennan et al. found in an initial assessment of adults ages 55–65 that, at the aggregate level, 86% of men and 91% of women reported consuming alcohol in the last month. Twenty years later, the percentage of individuals consuming alcohol was reduced but still high (78% for men and 77% for women). For both men and women, there was also a fair amount of intra-individual-level stability for the number of alcoholic drinks consumed per day from baseline to the 10-year assessment, with gradual declines in amount consumed occurring between the 10- and 20-year assessments. Likewise, in a nationally representative sample, at the aggregate level, Blazer and Wu found lower rates of abstention and low-risk drinking and higher rates of at-risk drinking and HED among 50- to 64-year-olds relative to those 65 and older, suggesting that problematic use of alcohol is higher in younger middle age and declines as people transition to older middle age.

Contrary to these findings, at the aggregate level, Platt et al. (2010)—with a sample of 51- to 61-year-olds at baseline—reported a decline in the number of drinks consumed per day and an increase in abstainers across a 15-year period, with the greatest change occurring in the first 5 years of the study, earlier than that reported by Brennan et al. (2011). In a longitudinal study of middle-aged adults, Molander et al. (2010) found that from age 53 (Time 1) to age 64 (Time 2), at the aggregate level, the average number of drinks per drinking day and heavy drinking decreased, but the frequency of drinking increased among both men and women. Thus, although there is a gradual decline in alcohol involvement with increasing age, there is ambiguity as to the levels of stability and change during the middle adult years, and this is especially the case for indicators of more moderate alcohol use versus problematic use.

Mutual influences between partners on alcohol use in middle-aged couples

Among middle-aged and older adult couples in long-term romantic relationships (e.g., marriage, cohabitation), research findings suggest reciprocal effects between partners in relation to their social activities (Hoppmann et al., 2008), levels of happiness (Hoppmann et al., 2011), subjective well-being (Bookwala and Schulz, 1996), and health status (Cronkite and Moos, 1984; Strawbridge et al., 2007). For example, using 35-year longitudinal data, Hoppmann et al. (2011) found that happiness levels between spouses (intercepts) were significantly correlated and that the rate of change in levels of happiness (i.e., the slopes) was highly similar. They concluded “that spouses not only report relatively similar happiness but also that happiness waxes and wanes in relation to the respective partner” (p. 4).

In the domain of alcohol involvement, longitudinal research using mutual influence models has not yet tested the bidirectional effects of middle-aged couples’ influence on each other’s alcohol use. Although statistically not the same as mutual influence models, some studies have focused on the concordance and discordance of alcohol use among couples of various ages. Results have indicated both concordance and discordance, with the more robust pattern being one of concordance in couples’ alcohol involvement; that is, couples tend to be more similar than dissimilar in their alcohol use with respect to drinking (vs. not drinking), frequency of drinking and of heavy drinking, and the volume of alcohol consumed (Demers et al., 1999; Gleiberman et al., 1992; Graham and Braun, 1999; Homish et al., 2009; Moos et al., 2011). These findings are consistent with the idea that similarity in alcohol use among couples occurs, at least in part, as a consequence of partners’ mutual influence on each other’s drinking.

Recently, the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Cook and Kenny, 2005; Kenny and Ledermann, 2010) has provided a data analytic approach to specify and evaluate hypotheses about interdependence within dyadic relationships. For distinguishable dyads, such as marital couples, the APIM facilitates the estimation of both actor and partner effects so that questions such as “How much does Partner A’s behavior contribute to Partner B’s behavior” and “How much does Partner B’s behavior contribute to Partner A’s behavior” can be investigated simultaneously. In longitudinal applications, “actor effects” are accounted for by the individual-level stability of each partner’s behavior across time, whereas “partner effects” are accounted for by cross-lagged influences. Hence, the model provides estimates for effects that are attributable to stable characteristics of a person (the actor) and effects that are attributable to the partner’s impact while statistically controlling for dyadic non-independence (Cook and Kenny, 2005). The APIM has been used to investigate bidirectional relationships in alcohol involvement for dating partners (Mushquash et al., 2013) and newlyweds (Leonard and Mudar, 2004) but, to our knowledge, has not been used to test those relationships in middle-aged marital dyads.

Goals and hypotheses of the current study

To meet the first goal of this study, three-wave data from 597 men and 847 women were used to evaluate both aggregate-level changes and individual-level stability and change with regard to (a) the prevalence of alcohol consumption, (b) average number of drinks consumed per day, and (c) prevalence of HED among middle-aged men and women. In addition to the aggregate level of changes on these alcohol characteristics at each of three waves of measurement, we also statistically modeled individual-level stability and change. Providing data both on aggregate- (or group) level and individual-level stability and change is a more comprehensive approach to studying these alcohol characteristics. For example, it is possible that aggregate-level stability could be indicated with these data (e.g., a similar percentage of HED at each wave) but that there is individual variation among participants across time such that those individuals reporting HEDs were not the same at each wave. Such a finding would yield high aggregate-level stability but low individual-level stability.

The second goal of the study was to use an APIM analytic strategy to model the bi-directional relationships of alcohol use with our sample of middle-aged marital dyads. These marital dyads were a subsample of 489 couples (from the larger sample) in which both wife and husband participated. Our three study hypotheses were as follows: First, we hypothesized that there would be both statistically significant actor and partner effects for husbands and wives. Second, because one’s prior behavior is often the strongest predictor of one’s subsequent behavior, we hypothesized that the actor effects would be significantly larger than the partner effects. Third, previous research has found that the magnitude of partner effects is (a) fairly comparable between men and women (Mushquash et al., 2013), (b) stronger from women to men (Moos et al., 2011), (c) stronger from men to women (Zucker et al., 2006), and (d) variable across time (Leonard and Mudar, 2004). Because adults in this sample were closer in age to individuals in the Moos et al. study, we hypothesized that there would be significant differences in the strength of the partner effects, with wives’ alcohol use having a stronger effect on husbands’ alcohol use than husbands’ alcohol use having on wives’ alcohol use.

Method

Participants

The data used in this study were collected from the parents of adolescents who had participated at Waves 5, 6, and 7 as part of a larger, seven-wave, 23-year prospective study focused on risk factors for adolescent and young adult substance use and mental health (see Windle et al., 2005). The first four waves of the study focused on adolescents, and a primary caregiver’s participation was limited to reporting on potential risk factors for adolescents (e.g., family income, parent’s education levels) via mail surveys (adolescents were assessed in school settings). The study design and focus shifted during Waves 5–7 in that assessments occurred at three 5-year intervals, the primary targets for study were expanded to include not only the adolescents as they transitioned to young adulthood but also the parents of these young adult children, and interviews were conducted with each participating member. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University at Buffalo. Signed informed consent was obtained from participants before each wave of assessment.

The participation rate for the adolescent sample was 76% (n = 1,205), which is relatively high for in-school assessments that require active informed consent (Tigges, 2003). At Waves 5–7, the study retained 87% of the adolescent sample (n = 1,050); participants were lost primarily because of difficulties in contacting them and also to refusals. Among this sample of 1,050 adolescents, the following data refer to their parents who were contacted for participation at Waves 5–7. For women (mothers of the adolescents), 47 (4.5%) died at some point between Wave 5 and Wave 7, 156 (14.8%) did not participate, and 847 (80.7%) participated, yielding a participation rate of 84% if the deceased are excluded from the denominator. For men (fathers of the adolescents), analogous statistics were 103 (9.8%) were deceased, 350 (33.3%) did not participate, and 597 (56.9%) participated, yielding a participation rate of 63% if the deceased are excluded from the denominator. Although this reflects a lower participation rate than preferred, it exceeds the standard rate of participation by fathers in behavioral science studies of families (Phares and Compas, 1992). Across the three waves of assessment, the retention rate for men was 72% (Wave 5–Wave 6) and 86% (Wave 6–Wave 7); for women it was 73% (Wave 5–Wave 6) and 85% (Wave 6–Wave 7).

Attrition analyses for those who participated at Wave 5 only (94 women, 65 men) versus those who participated at two or more occasions from Wave 5 to Wave 7 indicated no significant differences on alcohol use, HED, or sociodemographic variables, with the exception that women who dropped out had slightly lower levels of educational attainment. Similarly, attrition analyses among those for whom we had data and those who died during Waves 5–7 indicated that there were no significant differences with regard to alcohol use or HED.

For those surviving participants with data on one or more waves of measurement (597 men and 847 women), missing value estimation using the expectation-maximization algorithm was used to estimate the missing data under the missing-at-random assumption; approximately 20% of the data were estimated across the three waves of assessment. For the 847 women, the average number of years of education was 13.63 (SD = 1.92); average family income was around $37,000–$39,000; and average age was 50.28 years (SD = 4.37) at Wave 5, 55.31 years (SD = 4.78) at Wave 6, and 59.67 years (SD = 4.51) at Wave 7. For the 597 men, the average number of years of education was 14.32 (SD = 2.14); average family income was around $56,000–$58,000; and average age was 52.52 years (SD = 5.01) at Wave 5, 57.83 years (SD = 5.12) at Wave 6, and 61.84 years (SD = 5.24) at Wave 7. The sample was more than 99% White.

For the subset of 489 marital dyads, ages at Wave 5 were 50.14 years (SD = 4.67) for wives and 52.61 years (SD = 5.55) for husbands. The average length of marriage at Wave 5 was 26.07 years (SD = 8.21). On other characteristics (e.g., number of drinks consumed, HED), there were no significant differences between men and women who were married couples and who participated in the study and between men and women who were either unmarried or did not have a spouse participate.

Procedure

At Wave 5 and Wave 6, one-on-one interviews were conducted either in the subjects’ homes or at the investigators’ host institute. Subjects were paid $40 to complete an interview that lasted approximately 2 hours. Computer-assisted personal interviews were used to collect data. At Wave 7, because of budgetary cuts, mail surveys were completed by participants and returned in self-addressed, stamped envelopes.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables.

Participants were asked about their age, number of years of education completed, family income, length of marriage, and other status indicators (e.g., occupational status).

Alcohol use.

Alcohol use was measured with a standard quantity–frequency index (QFI) that assessed consumption of beer, wine, and distilled spirits in the past 6 months (Armor and Polich, 1982). Respondents were asked how often they usually had each beverage in the last 6 months (1 = never to 7 = every day) and, when they had the beverage, on average how much they usually drank (10-point scale from 1 = none to 10 = more than 8 cans, bottles, or glasses, depending on the beverage). A QFI of 0.5 oz. of ethanol was equal to 1 drink. To relate our findings to indexes used in the literature, we derived scores for both average ounces of ethanol consumed per day and the number of drinks consumed per day. We used a 6-month window to derive these scores to increase the probability of capturing drinking patterns that could be missed using a briefer time window (e.g., last 30 days). HED was assessed with questions about the frequency of drinking six or more alcoholic beverages on a single occasion and was similarly assessed over the last 6 months for each alcoholic beverage (i.e., beer, wine, distilled spirits), and a summed score was created to measure the number of occasions of HED.

Guided by past definitions (Moore, 2003; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007) and studies (Blazer and Wu, 2009) of at-risk drinking among middle-aged and older adults, in this study we defined “risky” drinking to categorize participants into three groups: no use, low risk (for men equal to or less than two drinks a day; for women equal to or less than one drink a day), and at risk (for men greater than two drinks a day; for women greater than one drink a day).

Statistical analyses plan

Descriptive analyses for drinks per day and HED were provided for each wave to evaluate aggregate levels of change in alcohol use characteristics across time. To evaluate individual-level change (i.e., intra-individual change), autoregressive path models were specified and included the three covariates of age, level of educational attainment, and household income. We used the full sample rather than restricting analyses to drinkers only. The APIM was specified, estimated, and evaluated using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012). The three-wave model specification included the simultaneous estimation of actor effects (or estimates associated with within-person stability across time), partner effects (or estimates of cross-lagged effects of partner’s alcohol use at occasion t − 1 on other partner’s alcohol use at occasion t), and correlations among wives’ and husbands’ residual scores for alcohol use at each of the three occasions of measurement. The adequacy of fit for the specified models was determined by conventional goodness-of-fit cut-offs (Hu and Bentler, 1999), including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values less than .05 indicating good fit and values as high as .08 representing acceptable fit (Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Steiger, 1990); the comparative fit index (CFI), with values greater than .90 and .95 reflecting acceptable and good model fit, respectively; and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), with a value less than .08 indicating good model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Results

Prevalence of alcohol use across time

Findings on alcohol characteristics for men and women across the three waves of measurement are summarized in Table 1. The findings indicate high rates of consuming alcohol at each wave for both men and women; furthermore, at the aggregate level, the prevalence is highly similar across waves. For the average number of drinks consumed per day, men drank more than twice as much as women and averaged between 1.64 and 1.82 drinks per day. At the individual level, on the basis of a repeated-measures general linear model (GLM), there was not significant change in the average number of drinks per day for either men, F(2, 595) = 1.26, p > .05, or women, F(2, 845) = 1.83, p > .05. Similar to the findings for drinks consumed per day, more than twice as many men as women reported HED, although in the aggregate the prevalence of HED was similar within sex across occasions for both sex groups (i.e., there was aggregate-level stability for both sex groups). At the individual level, a repeated-measures GLM indicated significant decreases across time for number of HED occasions for men, F(2, 595) = 4.58, p < .05, and women, F(2, 845) = 4.23, p < .05. The percentage at risk was similar for men and women and ranged from 9.2% to 11.6%; the vast majority of participants were categorized as low risk. There were no statistically significant differences between men and women at each wave with regard to their representation across drinking risk categories. At Wave 5, χ2(2) = 3.30, p > .05; at Wave 6, χ2(2) = 1.93, p > .05; and at Wave 7, χ2(2) = 1.87, p > .05.

Table 1.

Aggregate-level alcohol use characteristics for men and women for three waves of measurement

| Variable | Wave 5 |

Wave 6 |

Wave 7 |

|||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Percentage consuming alcohol, last 6 months | 88.8 | 86.5 | 85.3 | 82.9 | 85.1 | 82.5 |

| Mean number of drinks per day | 1.82 | 0.68 | 1.68 | 0.76 | 1.64 | 0.72 |

| Percentage with heavy episodic drinking, last 6 months | 38.7 | 13.7 | 32.2 | 11.9 | 38.7 | 10.6 |

| Alcohol risk status, % | ||||||

| No use | 11.2 | 13.5 | 14.7 | 17.1 | 14.9 | 17.5 |

| Low risk | 77.2 | 77.3 | 73.8 | 72.7 | 74.1 | 72.5 |

| At risk | 11.6 | 9.2 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 11.0 | 10.0 |

Individual-level stability

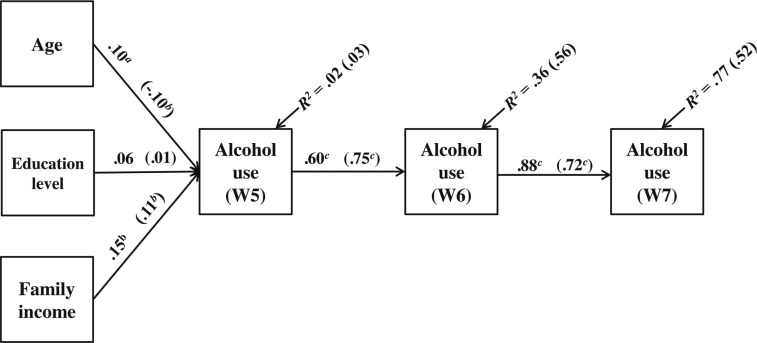

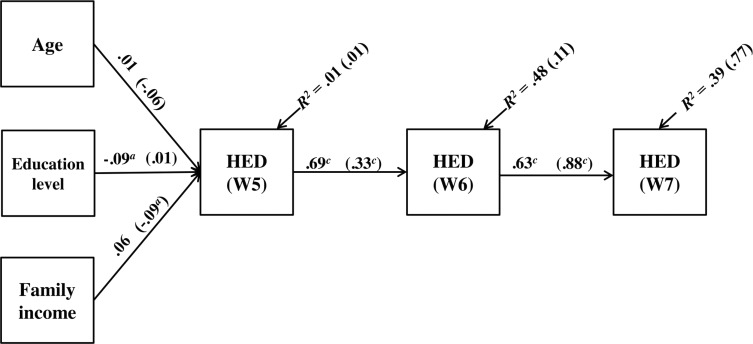

Autoregressive path models were used to evaluate individual-level change (i.e., the rank order stability of individuals across time). Figure 1 summarizes the findings for the average number of drinks per day, and good model fit was indicated for men, χ2(7) = 26.54, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .04; and for women, χ2(7) = 55.64, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .09, SRMR = .04. A simultaneous group model in which the autoregressive (stability) coefficients were constrained to equivalence across sex groups was also specified but was rejected, χ2(2) = 183.46, p < .001, thereby indicating that the magnitude of the stability coefficients was not equal across sex groups. The coefficients in Figure 1 indicate high stability across time for men and women, with men somewhat more stable than women between Wave 6 and Wave 7, and women somewhat more stable than men between Wave 5 and Wave 6. Figure 2 summarizes a similarly specified model for HED; fit statistics indicated good model fit for men, χ2(7) = 18.78, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .05, and for women, χ2(7) = 49.97, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .07. High levels of stability were indicated for men and for women between Wave 6 and Wave 7 but only low to moderate stability for women between Wave 5 and Wave 6. Overall, the findings indicate a relatively high level of individual-level stability across time for average number of drinks per day and HED.

Figure 1.

Autoregressive model of alcohol use for men and women. Standardized path coefficients provided for men and women (in parentheses). W = wave. ap < .05; bp < .01; cp < .001.

Figure 2.

Autoregressive model of heavy episodic drinking (HED) for men and women. Standardized path coefficients provided for men and women (in parentheses). W = wave. ap < .05; cp < .001.

Tests of partner mutual influence

The correlation matrix used for the APIM is provided in Table 2. The specified model consisted of wives’ and husbands’ respective ages and education levels, family income, and length of marriage as covariates predicting Wave 5 alcohol use for wives and husbands, respectively. Actor effects were modeled as autoregressive coefficients (i.e., t − 1 on t), and cross-lagged effects corresponded to partner effects. Residuals of the equations at each occasion of measurement for wives’ and husbands’ alcohol use were allowed to correlate to accommodate the non-independence of the dyadic unit (Cook and Kenny, 2005). The resulting model is provided in Figure 3 and, based on our multiple fit indexes, provided a plausible fit to the data, χ2(32) = 132.36, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .04. As expected, the actor effects (stability coefficients) were statistically significant for both husbands and wives across the two prospective time frames. The partner effects were also statistically significant from wives to husbands across the two prospective time frames. However, for the partner effects from husbands to wives, only the cross-lagged coefficient from Wave 5 to Wave 6 was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for actor–partner interdependence models for alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. |

| 1. H Wave 5 age | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. W Wave 5 age | .74c | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. H Wave 5 yrs. education | -.03 | .02 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. W Wave 5 yrs. education | .05 | .11a | .40c | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Wave 5 income | -.16c | -.09a | .37c | .32c | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 6. Wave 5 yrs. married | .34c | .42c | .00 | -.05 | -.12b | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 7. H Wave 5 alcohol use | .03 | -.02 | .01 | .01 | .10a | .00 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 8. H Wave 5 HED | -.08 | -.06 | -.03 | .01 | .05 | .04 | .45c | 1 | ||||||||||

| 9. H Wave 6 alcohol use | .03 | -.02 | .03 | .05 | .09a | .02 | .84c | .43c | 1 | |||||||||

| 10. H Wave 6 HED | -.15b | -.13b | -.04 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .35c | .66c | .41c | 1 | ||||||||

| 11. H Wave 7 alcohol use | .05 | -.02 | .06 | .08 | .12a | .01 | .79c | .37c | .87c | .35c | 1 | |||||||

| 12. H Wave 7 HED | -.09a | -.08 | -.09a | -.07 | .03 | .05 | .36c | .35c | .33c | .45c | .40c | 1 | ||||||

| 13. W Wave 5 alcohol use | -.02 | -.02 | .07 | .10a | .14b | -.05 | .26c | .26c | .35c | .09 | .39c | .06 | 1 | |||||

| 14. W Wave 5 HED | -.01 | -.07 | -.04 | .00 | .02 | -.05 | .19c | .16c | .25c | .05 | .27c | .04 | .42c | 1 | ||||

| 15. W Wave 6 alcohol use | -.02 | -.03 | .06 | .08 | .15b | .00 | .32c | .17c | .42c | .10a | .48c | .10a | .74c | .41c | 1 | |||

| 16. W Wave 6 HED | -.03 | -.07 | -.06 | -.05 | -.01 | -.01 | .06 | .07 | .10a | .05 | .09a | .05 | .11a | .51c | .26c | 1 | ||

| 17. W Wave 7 alcohol use | .00 | -.04 | .08 | .11a | .12a | -.02 | .26c | .08 | .36c | .10a | .46c | .09 | .66c | .50c | .77c | .22c | 1 | |

| 18. W Wave 7 HED | -.06 | -.09 | -.03 | -.03 | .04 | -.03 | .15b | .08 | .18c | .07 | .21c | .22c | .11a | .39c | .16c | .35c | .26c | 1 |

| M | 52.61 | 50.14 | 14.61 | 13.95 | 6.461 | 26.07 | 11.01 | 0.65 | 11.01 | 0.40 | 11.14 | 0.53 | 4.36 | 0.08 | 4.96 | 0.13 | 5.55 | 0.07 |

| SD | 5.6 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 8.2 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 19.2 | 1.2 | 18.1 | 1.4 | 7.9 | 0.3 | 9.0 | 0.9 | 10.4 | 0.4 |

Notes: H = Husband; W = wife; yrs. = years; HED = heavy episodic drinking.

Income categories: 1 = less than $6,000 to 8 = $55,000 or more.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Actor–partner interdependence model for marital dyads’ alcohol consumption. W = wave; D = residuals of the equations. ap < .05; bp < .01; cp < .001.

To test our hypothesis that the cross-lagged partner effects would differ statistically, with stronger effects indicated for the wives-to-husbands coefficients, we specified and estimated a partner-symmetry model in which the cross-lagged partner coefficients were constrained to equivalence between Wave 5 and Wave 6 and between Wave 6 and Wave 7. The resulting model did not provide as good of fit to the data because the chi-square difference test indicated a significant decrement in statistical fit, χ2(2) = 17.18, p < .001. Thus, our hypothesis of asymmetric relations between partner effects was supported in that wives had a more potent effect on husbands’ alcohol use than husbands did on wives’ alcohol use.

We specified and estimated a similar cross-lagged model for couple HED (data not shown). The overall model provided a plausible representation of the data, χ2(32) = 73.62, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .04. However, with regard to the APIM, only the actor effects were statistically significant (all ps < .001); none of the partner effects were statistically significant.

Discussion

An objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of alcohol use characteristics in a sample of middle-aged men and women, along with the aggregated (group) and individual levels of stability and change across a 10-year period. We found that an equally high percentage of men and women reported consuming alcohol at each of the three measurement occasions and that these percentages were, in general, similar across the three waves. Similarity across waves for the respective groups of men and women was also indicated for average number of drinks per day and HED, although men reported more than twice the level of average drinks per day relative to women; in addition, more than twice the percentage of men reported HED relative to women. Based on previous research and our findings, we conclude that the majority of middle-aged adults consume alcohol, although the percentages in our community sample are somewhat higher than those in some nationally representative samples where a shorter time window (e.g., last-3-months’ use) has been used (Platt et al., 2010). A shorter time window for assessment may decrease the prevalence of use relative to a longer time window because it permits more time for a drinking occasion to occur; moreover, it may influence the average number of drinks per day because if no drinking is reported for the shorter time window, the average number of drinks per day is “zero,” whereas a longer time window may yield a nonzero value if drinking occurs. The percentage of drinkers in our community sample was quite similar to that found in Brennan et al.’s (2011) community sample.

With regard to the average number of drinks per day, our findings are largely similar to those reported in the literature, especially given that there is variation across studies with regard to the time windows used to assess alcohol use (e.g., last-30-days, last-6-months, last year), differences in survey items (e.g., a single item requesting number of alcoholic beverages or drinks consumed vs. alcoholic beverage–specific items for beer, wine, and distilled spirits), and alternative demarcations for age groupings of middle-aged versus older adults (Blazer and Wu, 2009; Brennan et al., 2011; Breslow and Smothers, 2004; Kaplan et al., 2012; Molander et al., 2010; Platt et al., 2010; Sacco et al., 2009).

For example, Brennan et al. (2011) reported that across the 20 years of their study, the average number of drinks consumed per day ranged from 1.10 to 1.52 drinks for men and 0.57 to 1.34 drinks for women. Our sample yielded average rates of drinking per day from 1.64 to 1.82 for men and from 0.68 to 0.76 for women. Similarly, Breslow and Smothers (2004) reported that among men 60 years and older who had consumed alcohol in the past year, 80% reported consuming two drinks or less per day on drinking days; for women, the percentage was 93.6%. Our rates, excluding abstainers, were 86% for men and 89% for women. Our rates of HED were higher for men and to a lesser extent women than some studies reported in the literature. Our rates for men ranged from 32% to 38%, and our rates for women ranged from 10% to 13%; Blazer and Wu (2009) reported rates of 23% for men and 9% for women. However, the Blazer and Wu study used a 30-day window to assess HED, and we used a 6-month window. Breslow and Smothers reported rates of HED for men who drank at 28.3% and 7.4% among women who drank; a 1-year window was used for this assessment.

Hence, despite variability in the time windows used to assess alcohol use characteristics, conclusions are similar across studies in suggesting that some level of light to moderate (or low-risk) drinking occurs frequently among middle-aged adults, although there is variability in the amount of alcohol consumed and the percentage engaging in HED, thus suggesting that a minority subset of drinkers are at risk for alcohol-related problems during middle age and beyond (Blazer and Wu, 2009; Breslow and Smothers, 2004; Platt et al., 2010; Sacco et al., 2009).

In terms of risky drinking as defined in this study (see Method section), the findings indicated that between 9% and 11% of the sample were at risk for adverse consequences, with equal representation of men and women. This estimated level of risk using this index is somewhat lower than those reported by Blazer and Wu (2009), who reported rates of 19% for men and 13% for women (for age range 50–64 years). However, our rates of HED were somewhat higher for men (32%–38%) and women (10%–13%) than those reported by Blazer and Wu for men (23%) and women (9%). Nevertheless, the general findings across these two studies were similar in that the majority of the respective samples were not at high risk for more serious alcohol-related problems, and most samples could be characterized in the light to moderate or low-risk range.

With regard to individual-level stability, our findings supported relatively high rank-order stability for the average number of drinks per day and HED for men and women. These findings are similar to those reported by Brennan et al. (2011); that is, in their sample, which was similar to ours in terms of age (middle age), ethnicity (predominantly White), and socioeconomic status (predominantly middle to upper-middle class), their average number of drinks per day was stable at the individual level from ages 60 to 70 years and remained moderately stable even across a 20-year interval. Kaplan et al. (2012) also found substantial individual-level stability in the 6-year drinking patterns of their nationally representative sample of middle-aged (≥50 years) Canadians.

Findings from the APIM supported our hypotheses of greater actor stability in alcohol use, with smaller magnitude partner effects. In addition, within the context of mixed findings related to women’s and men’s influence on their partners’ drinking (Leonard and Mudar, 2004; Moos et al., 2011; Mushquash et al., 2013; Zucker et al., 2006), our findings indicated that wives’ drinking had a greater influence and was more consistent on their husbands’ drinking than vice versa. That is, from Wave 5 to Wave 6, husbands and wives mutually influenced each other’s drinking, but from Wave 6 to Wave 7, only the wives’ influence on their husbands’ drinking was significant.

Within the adolescent literature, the social processes of selection and influence have been conceptualized as important proximal factors that affect teens’ tobacco, alcohol, and other substance use (Ennett and Bauman, 1994; Reed and Rountree, 1997). For the current sample of middle-aged husbands and wives in long-term marriages, the initial partner selection effects were likely to have occurred years before and thus were part of a dyadic process that was not evaluated in the specified APIM. However, social influences associated with the roles of wives may account, at least in part, for our findings that wives had a greater impact on their husbands’ drinking than husbands had on their wives’ drinking. For example, wives may be more influential in selecting the couples’ social outlets, such as choosing friends and acquaintances with whom to spend leisure time, with these choices involving higher (or lower) levels of alcohol use.

This study has limitations that merit consideration when interpreting the findings. First, the sample was not a representative sample but rather was predominantly White and middle class, and had, on average, higher education levels. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to more representative populations. However, these findings provide insights into the drinking behaviors of an understudied segment of the population, that is, middle-aged adults (relative, for example, to adolescents/young adults and the elderly). Second, the data were collected by means of self-reports, which may have introduced mono-method bias that may have affected the resulting findings. Third, the 5-year measurement intervals may have masked considerable changes in drinking behaviors that occurred during the intervening periods; a more intensive longitudinal design with shorter intervals between measurement occasions may have yielded more dynamic patterns of changes in alcohol use. Finally, future research would benefit from including the mutual influences of drinking problems.

In summary, a majority of middle-aged adults engage in alcohol use and, in the current study, displayed relatively high aggregate-level stability and individual stability across the 10-year window. Men drank higher quantities of alcohol, and a higher percentage was more likely to engage in HED than women. Marital partners in long-term relationships had significant but modest effects on each other’s alcohol use, although wives’ impact on husbands was greater than husbands’ impact on wives.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R21AA 020047 and K05AA021143. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Anttila T, Helkala E-L, Viitanen M, Kåreholt I, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B, Kivipelto M. Alcohol drinking in middle age and subsequent risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in old age: A prospective population based study. BMJ. 2004;329:539–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38181.418958.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armor DJ, Polich JM. Measurement of alcohol consumption. In: Pattison EM, Kaufman E, editors. Encyclopedic handbook of alcoholism. New York, NY: Gardner Press; 1982. pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Wu L-T. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, Schulz R. Spousal similarity in subjective well-being: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:582–590. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS, Moos RH. Twenty-year alcohol-consumption and drinking-problem trajectories of older men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:308–321. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow RA, Smothers B. Drinking patterns of older Americans: National Health Interview Surveys, 1997-2001. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:232–240. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Hardy CL. Alcohol consumption and health status in older adults: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21:824–847. doi: 10.1177/0898264309340688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM. Heavy/binge drinking and depressive symptoms in older adults: Gender differences. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011a;26:860–868. doi: 10.1002/gps.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM. Psychological distress, binge/heavy drinking, and gender differences among older adults. American Journal on Addictions. 2011b;20:420–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cronkite RC, Moos RH. The role of predisposing and moderating factors in the stress-illness relationship. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1984;25:372–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers A, Bisson J, Palluy J. Wives’ convergence with their husbands’ alcohol use: Social conditions as mediators. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:368–377. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleiberman L, Harburg E, DiFranceisco W, Schork A. Familial transmission of alcohol use: V. Drinking patterns among spouses, Tecumseh, Michigan. Behavior Genetics. 1992;22:63–79. doi: 10.1007/BF01066793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Braun K. Concordance of use of alcohol and other substances among older adult couples. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:839–856. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Kozlowski LT, Cornelius JR. The longitudinal association between multiple substance use discrepancies and marital satisfaction. Addiction. 2009;104:1201–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann CA, Gerstorf D, Luszcz M. Spousal social activity trajectories in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing in the context of cognitive, physical, and affective resources. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63:P41–P50. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.1.p41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann CA, Gerstorf D, Willis SL, Schaie KW. Spousal interrelations in happiness in the Seattle Longitudinal Study: Considerable similarities in levels and change over time. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1–8. doi: 10.1037/a0020788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Feeny D, McFarland BH, Caetano R, Bernier J, Ross N. Alcohol use patterns and trajectories of health-related quality of life in middle-aged and older adults: A 14-year population-based study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:581–590. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Sarkisian CA, Kado DM, Dedes H, Liao DH, Kim S, Moore AA. Light to moderate alcohol consumption and disability: Variable benefits by health status. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169:96–104. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Ledermann T. Detecting, measuring, and testing dyadic patterns in the actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:359–366. doi: 10.1037/a0019651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Wallace RB, Huppert FA, Melzer D. Moderate alcohol consumption in older adults is associated with better cognition and well-being than abstinence. Age and Ageing. 2007;36:256–261. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Mudar P. Husbands’ influence on wives’ drinking: Testing a relationship motivation model in the early years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:340–349. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JC, Guerrieri JG, Moore AA. Drinking patterns and the development of functional limitations in older adults: Longitudinal analyses of the health and retirement survey. Journal of Aging and Health. 2011;23:806–821. doi: 10.1177/0898264310397541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molander RC, Yonker JA, Krahn DD. Age-related changes in drinking patterns from mid- to older age: Results from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1182–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. Clinical guidelines for alcohol use disorders in older adults. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, Moos BS. Personal, family and social functioning among older couples concordant and discordant for high-risk alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2011;106:324–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushquash AR, Stewart SH, Sherry SB, Mackinnon SP, Antony MM, Sherry DL. Heavy episodic drinking among dating partners: A longitudinal actor-partner interdependence model. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:178–183. doi: 10.1037/a0026653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998-2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician s guide. Updated 2005 edition. Bethesda, MD: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas BE. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt A, Sloan FA, Costanzo P. Alcohol-consumption trajectories and associated characteristics among adults older than age 50. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:169–179. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JR, Young AF. Longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and health of middle-aged women in Australia. Addiction. 2008;103:424–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MD, Rountree PW. Peer pressure and adolescent substance use. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1997;13:143–180. [Google Scholar]

- Roerecke M, Rehm J. Irregular heavy drinking occasions and risk of ischemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171:633–644. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P, Bucholz KK, Spitznagel EL. Alcohol use among older adults in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions: A latent class analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:829–838. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Shema SJ. Impact of spouse vision impairment on partner health and well-being: A longitudinal analysis of couples. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:S315–S322. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.5.s315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigges BB. Parental consent and adolescent risk behavior research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Mun EY, Windle RC. Adolescent-to-young adulthood heavy drinking trajectories and their prospective predictors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:313–322. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Wong MM, Clark DB, Leonard KE, Schulenberg JE, Cornelius JR, Puttler LI. Predicting risky drinking outcomes longitudinally: What kind of advance notice can we get? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:243–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]