Abstract

Background

In order to protect the rights of the mentally ill, legislation on the standards and procedures of compulsory detention has been made at the local and national level in China.

Aims

This study aims to examine psychiatrists’ attitude to seeking involuntary admission in China mainland.

Method

Three hundred and fourteen qualified members of Chinese Psychiatrist Association (CPA) were surveyed using a questionnaire to assess their attitudes about the procedure of involuntary admission to mental hospitals. Data were analyzed using chi-squares and logistic regression.

Results

Some psychiatrists in CPA had several arbitrary attitudes in the process of admission. Female, age under 35, low education level and low position in institution are associated with stricter attitudes in the procedure of involuntary admission. Areas with mental health legislation showed significant positive relations with stricter attitudes.

Conclusions

Every effort needs to be made to minimize these arbitrary attitudes to prevent negative outcomes. Protecting the rights of people diagnosed with mental illness still has a long way to go.

Keywords: Attitude, Involuntary admission, Informed consent, Proxy consent, Legislation

Introduction

Traditionally, human rights of mental patients have not been properly protected in China (Yip, 2005). There was inadequate protection against compulsory detention and patients’ informed consent to treatment is often lacking (Pearson, 1992). In 2002, a survey in 17 cities found that among 2333 psychiatric inpatient admissions, only 18.5 % were voluntary (Pan, Xie, & Zheng, 2003). According to Li’s survey (Li, Liu, & Ma, 2006), 60.8% of the patients diagnosed with schizophrenia were brought to hospitals by their guardians without being informed before hospitalization.

In order to protect the rights of the mentally ill, legislation on the standards and procedures of compulsory detention has been made at the local level (Shanghai in 2002, Ningbo and Beijing in 2006, Hangzhou and Wuxi in 2007, Wuhan in 2010) and in the draft of the National Mental Health Law. In these mental health statutes, there are similar articles which preferred voluntary admission and the conditions of involuntary admission are generally restricted. The most common standard for involuntary commitment is “danger to oneself or others” in “Emergency Hospitalization” procedure (with 72 hours’ time limitation). To patients who are unable to give informed consent but require admission and treatment, “Medical Protection Hospitalization” procedure can be performed at the request of the patient’s guardian if the criterion “totally or partially lose the competence of insight (the ability of knowing, understanding and making proper presentation of one’s abnormal mental state and morbid act)” (Shanghai), “grave impairment in mental activities that lead to personal health conditions, external reality cannot be fully identified or behaviors cannot be controlled” (Beijing & Wuxi), or “cannot (entirely) recognize or control one’s own behaviors” (Hangzhou & Ningbo) is met. The core principle of these criterion is the “impairment of mental function” and “need for treatment.” Such standards are similar with the criteria used in Europe (Luchins, Cooper, Hanrahan, & Rasinski, 2004; Brooks, 2006) and the U.S. (Roberts, Peay, & Eastman, 2002). Finally, the ultimate decision of admission and discharge is left to the capable patient him/her self or the incapable patient’s guardian or close relative. Furthermore, according to these statutes, both the expenditure for involuntary admission and voluntary admission is pay by patient and the family through medical insurance or their own expenses. Only those patients have no family and income will be State funded. By doing so, these regulations aim to standardize mental health professionals’ practices and protect the rights of patients with mental illness.

Till now it’s still unclear what kinds of attitude do China’s psychiatrists hold to the procedure of involuntary admission to mental hospitals. Since psychiatrists are seen as key stakeholders in the debates about involuntary commitment (Brooks, 2006), it is thus important to discern their attitudes toward various aspects of involuntary admission. A common method used in such research were self report questionnaires developed by researchers which may adopt direct question (Roberts, Peay, & Eastman, 2002; Brooks, 2006, 2007) or indirect case vignettes (scenarios) (Lepping, Steinert, Gebhardt, & Röttgersc, 2004; Luchins, et al., 2004). This study sought to explore psychiatrists’ self -reported attitudes to procedure of involuntary admission in China in order to obtain baseline information before the National Mental Health Law is enforced in the near future. Besides, previous studies found that mental health professionals’ support attitude for involuntary admission may related to level of training (Pirzada Sattar, Pinals, Din, & Appelbaum, 2006) or age (Lepping, et al., 2004). Thus we also investigated the relationships between certain characteristics of the psychiatrists (e.g. gender, different education level and position, age and whether or not come from area with mental health legislation) and their attitudes.

Methods

Study site

The participants of the study were nationwide representative members of Chinese Psychiatrist Association (CPA). CPA is a professional organization composed of licensed psychiatrists in China with the task to provide continuing education program to all the psychiatrists in China and to devise standardized psychiatric residency training program. There were 635 nationwide representative members of all its members at the time of recruitment (May 2010). Thus, though the sample is only a small part of the professional community compared to its huge size of 19130 psychiatrists and associate psychiatrists in total (Ministry of Health, 2005), these people’s attitudes and behaviors may have significant impacts on other psychiatrists’ clinical practice.

Recruitment

From May to June in 2010, an email attached with a questionnaire was sent to the recruited participants. In this email, it was told that the survey was not an official guidance document; it was simply for a research project. Besides, the results of the survey will not affect the assessment of his or her academic or clinical performance. After these explanations, they were instructed to respond to a set of questions. Also, the responders were asked to identify their age, gender, education level (3-year secondary medical school, 5-year medical college or postgraduate degree), position in the institutions (resident, attending or chief psychiatrist) and encounters with patients’ malpractice complaints. Reminder letter were sent to those who did not return the questionnaire in the beginning.

Questionnaire development

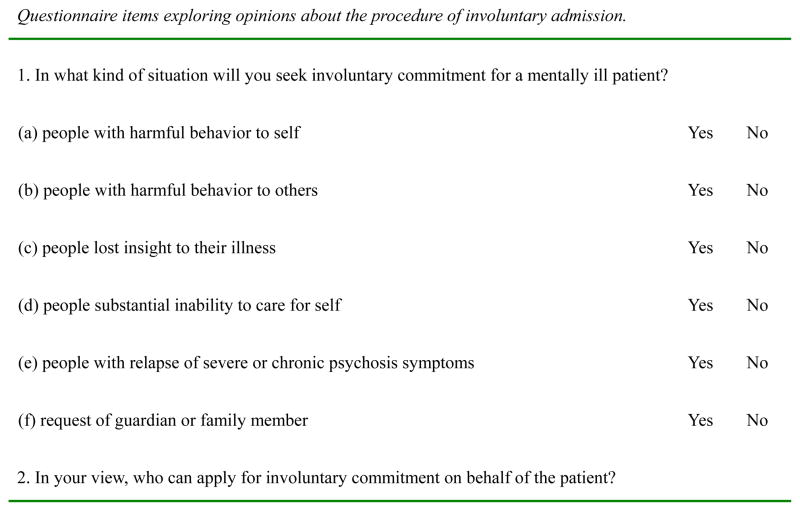

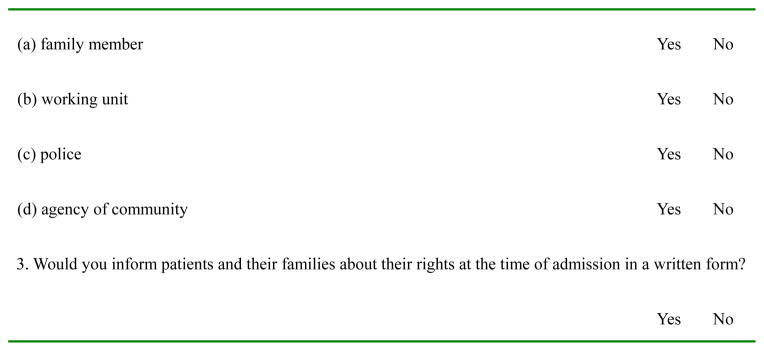

The self-report questionnaire was developed by our research team which includes three main questions (Figure 1). Question 1 addressed attitudes towards criterions for involuntary admission. Question 2 addressed attitudes towards who can apply for involuntary commitment on the behalf of patient. Question 3 addressed attitudes towards practice of inform concern. The responder was asked to mark their responses to these questions by “Yes” or “No”.

Figure 1.

Questionnaire items exploring opinions about the procedure of involuntary admission.

Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0. Descriptive statistics of the frequencies of the demographic variables of the study were first carried out. In comparison of the ratios of categorical variables, χ2-test was used for dichotomy variables and Mantel Haenszel χ2-test was used for ordinal variables. Additionally, logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the relationship between demographic variables and psychiatrists’ attitudes.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

By the end of July 2010, a total of 314 psychiatrists responded, giving a response rate of 49.4%. The rate is similar to other e-mail surveys of psychiatrists regarding the process of psychiatric hospitalization, such as 49% in Luchins’ (Luchins, et al., 2004) and 48.4% in Brooks’ (Brooks, 2006) study, but lower than 60% in Roberts’ (Roberts, et al., 2002).

The responders’ ages ranged from 23 to 61 years, with a mean of 36.5, a median of 35, and a standard deviation of 8.3 years. The demographic and descriptive information of the responders is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Positive responses to procedures and criterions in involuntary admission in different subgroups (%)

| n | Q1a | Q1b | Q1c | Q1d | Q1e | Q1f | Q2a | Q2b | Q2c | Q2d | Q3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | % | x2 | ||

| Total | 314 | 98.1 | 98.7 | 69.1 | 48.4 | 57.6 | 32.5 | 98.4 | 18.2 | 92.7 | 44.9 | 75.5 | |||||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Females | 156 | 98.1 | 0.000 a | 98.7 | 0.000 a | 65.4 | 2.014 | 35.9 | 19.428 *** | 47.4 | 13.230 *** | 28.8 | 1.871 | 98.7 | 0.191 a | 10.3 | 13.011 *** | 92.3 | 0.062 | 33.3 | 16.778 *** | 78.8 | 1.901 |

| Males | 158 | 98.1 | 98.7 | 72.8 | 60.8 | 67.7 | 36.1 | 98.1 | 25.9 | 93.0 | 56.3 | 72.2 | |||||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Below median | 149 | 98.7 | 0.489 a | 98.7 | 0.011 a | 65.8 | 1.479 | 30.2 | 37.634 *** | 43.0 | 25.062 *** | 33.6 | 0.149 | 98.7 | 0.113 a | 8.7 | 16.964 *** | 89.9 | 3.141 | 30.9 | 22.566 *** | 76.5 | 0.163 |

| Above median | 165 | 97.6 | 98.8 | 72.1 | 64.8 | 70.9 | 31.5 | 98.2 | 26.7 | 95.2 | 57.6 | 74.5 | |||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secondary school | 90 | 08.8 | 0.724 a | 100.0 | 2.610 a | 63.3 | 3.324 | 25.6 | 26.633 *** | 38.9 | 18.174 *** | 23.3 | 4.903 | 100.0 | 4.890 a | 8.9 | 7.289* | 95.6 | 6.849* | 32.2 | 9.916 ** | 80.0 | 5.235 |

| University | 155 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 69.0 | 58.7 | 65.2 | 36.8 | 98.7 | 21.9 | 94.2 | 52.9 | 77.4 | |||||||||||

| Postgraduate | 69 | 97.1 | 97.1 | 76.8 | 55.1 | 65.2 | 34.8 | 95.7 | 21.7 | 85.5 | 43.5 | 65.2 | |||||||||||

| Grade | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resident psychiatrist | 74 | 100.0 | 2.963 a | 100.0 | 1.255 a | 59.5 | 6.487 * | 14.9 | 52.998 *** | 29.7 | 36.618 *** | 33.8 | 0.664 | 100.0 | 1.929 a | 2.7 | 18.85 *** | 90.5 | 0.667 | 23.0 | 25.657 *** | 77.0 | 0.216 |

| Attending psychiatrist | 124 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 67.7 | 49.2 | 58.9 | 29.8 | 98.4 | 18.5 | 93.5 | 43.5 | 74.2 | |||||||||||

| Chief psychiatrist | 116 | 96.6 | 98.3 | 76.7 | 69.0 | 74.1 | 34.5 | 97.4 | 27.6 | 93.1 | 60.3 | 75.9 | |||||||||||

| City with Legislation | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 215 | 97.7 | 0.626 a | 98.6 | 0.080 a | 66.5 | 2.154 | 49.3 | 0.219 | 58.1 | 0.069 | 34.9 | 1.790 | 98.1 | 0.313 a | 21.4 | 4.825 * | 93.0 | 0.122 | 50.2 | 7.825 ** | 69.8 | 12.013 ** |

| Yes | 99 | 99.0 | 99.0 | 74.7 | 46.5 | 56.6 | 27.3 | 99.0 | 11.1 | 91.9 | 33.3 | 87.9 | |||||||||||

| Exposure to Complain | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 277 | 97.8 | 0.817 a | 98.6 | 0.541 a | 67.9 | 1.688 | 44.4 | 15.085 ** | 54.5 | 9.437 ** | 33.2 | 0.569 | 98.2 | 0.679 a | 17.3 | 1.075 | 92.4 | 0.228 | 41.5 | 10.908 ** | 75.8 | 0.142 |

| Yes | 37 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 78.4 | 78.4 | 81.1 | 27.0 | 100.0 | 24.3 | 94.6 | 70.3 | 73.0 | |||||||||||

More than 25.0% cells have expected count less than 5.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001; Note. Only positive responses to the items are shown in the table.

The medical education system varies greatly in China, from 3 years at secondary medical schools to 5–8 years at universities (Reynolds, & Tierney, 2004). The 3-year medical education programmes were set up in 1960s to produce doctors more quickly and training doctors for practice in underdeveloped (western or rural) areas. These 3-year graduates were trained in primary health care to the same level as 5-year graduates, but they did not have the training in the basic medical sciences, research skills and foreign languages that the graduates of 5-year programmes received (Lam, Wan, & Ip, 2006). While the 8-year programmes compose by 5-year formal medical train and aadditional 3 year postgraduate education. All graduates from these programmes should pass a national examination for medical graduates and work as an intern in a psychiatry hospital for a period of time (vary according to the education background) before they become a formal registered psychiatrist. In our survey, the majority of the psychiatrists who had responded had completed 5-year medical college or postgraduate education (71.3%). 76.4% of the responders were attending or even chief psychiatrist and 68.5% of them were coming from areas without mental health legislation.

About 11.8% of the responders had experienced malpractice claims.

Attitudes between different subgroups

In the criterion of involuntary admission (question 1), as can be seen in Table 1, most responders supported to use the “dangerous to self” (98.1%) and “dangerous to others” (98.7%) standard. Besides, a majority of responders also supported the criterion of “lost insight to their illness” (69.1%) and “relapse of severe or chronic psychosis symptoms” (57.6%). The support rate to “substantial inability to care for self” and “request of guardian or family member” as a criterion of involuntary admission was even low (48.4% and 32.5%). More over, there were significant differences on support rate on criterion of “lost insight to their illness” and “substantial inability to care for self” between different subgroups. Male, age over 35 (≥35), high education level (university or postgraduate education background), high position (attending or chief psychiatrist) responders and responders who had previous exposure to wrongful confinement complains were more likely to support these two criterions.

When came to the issue of who could make application of involuntary admission for mental illness patients (question 2), most responders said that they would accept the application from family member (98.4%) and police (92.7%). While the support rates to “agency of community” (44.9%) and “working unit” (18.2%) were not so high. Male, age over 35 (≥35), high education level (university or postgraduate education background), high position (attending or chief psychiatrist) responders and responders for areas without mental health legislation were more likely to support “agency of community” or “friend” as a substitute decision-maker to apply for involuntary admission. Responders who had previous exposure to wrongful confinement complains also were more likely to accept “agency of community” as a substitute decision-maker.

Finally, 75.5% of the responders reported that they would like to inform patient about their rights with a written form at the time of admission (question 4). Responders from areas with mental health legislation were significantly more likely to do so (87.9% vs. 69.8%, P < 0.01). No significantly relationships are found in this item with other variables.

Socio-demographic characteristics as predictors for attitudes

Multiple logistic regression analysis also yield similar results (table 2). Male, high age, high education level, high position responders and responders who had previous exposure to wrongful confinement complains were much arbitrary in concern the creations of involuntary admission and qualification for substitute decision-maker. While responders from areas with mental health legislation were stricter in qualification for substitute decision-maker and practice of inform concern.

Table 2.

Significant predictors of positive responses (logistic regression model, odds ratios)

| Q1a | Q1b | Q1c | Q1d | Q1e | Q1f | Q2a | Q2b | Q2c | Q2d | Q2e | Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female = 0, male = 1) | - | - | - | 1.931 * | 1.737 * | - | - | 2.661 ** | - | 1.745 * | 2.172 ** | - |

| Age (below median=0, above median=1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.632 * | 2.367 *** | - | - | ||

| Educationa | - | - | - | 1.484 * | 1.429 * | 1.724** | - | - | 0.439 * | - | - | - |

| Gradeb | - | - | 1.501 * | 2.731 *** | 2.284 *** | - | - | 2.253 *** | - | - | 1.908 *** | - |

| Legislation (no=0, yes=1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.472 * | - | 0.488 ** | 3.142 ** | ||

| Exposure to Complaint (no=0, yes=1) | - | - | - | 2.842* | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.256 | - |

1=Secondary medical school; 2=University; 3=Postgraduate

1=Resident psychiatrist; 2=Attending psychiatrist; 3=Chief psychiatrist

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

Discussion

This is the first study which investigates the reported attitudes about procedure of involuntary admission for mental illness in China. Some findings in our research contribute to our understanding the status quo of involuntary admission for mental illness in China.

First, most responders showed a positive attitude to accept “danger to self/others” as the criterion of involuntary admission and let the family member or police to practice as a legal representative during the process for proxy consent. Although it was after 2002 that the first local mental health legislation in Mainland China, the Shanghai Municipality Mental Health Regulations had been adapted and enacted, this does not mean that there was no law to deal with the admission and treatment for mental disordered patients. Many provinces or cities have municipal regulations about the involuntary admission and treatment for mental disordered patients with violence behavior. These regulations also stipulate the role of family member and police in such situation. Thus, in our survey, most responders had a similar attitude to these aspects.

Second, there were considerable responders had some arbitrary attitudes to the procedure of involuntary admission. These include neglect patient’s autonomy and ignore some basic rules in making decision on involuntary admission. For example, when came to the patients without obvious harmful behavior, things were much complicated. While the decision on admission is made primarily on the basis of clinical assessment and the diagnosis rendered. However, other, possibly unknown or obscure criteria may also have an important influence on the rate of admissions (Ziegenbein, Anreis, Brüggen, Ohlmeier, & Kropp, 2006 ). Even in those cities with mental health legislation, the principles like “impairment of mental function” and “need for treatment” were oversimplified and permitted different interpretations. As a result, different psychiatrist may have different understanding in such kinds of criterions, and reflected in our survey were while majority of responders supported the criterion of “lost insight to their illness” and “relapse of severe or chronic psychosis symptoms”, there were also some of responders supported to put patient who inability to care for self under custody. Further more, 32.5% of the responders admitted that they would involuntarily commit patients simply in response to the family’s demands. Such attitude may be caused by cultural traditions in China. Because of the cultural traditions, Chinese people prefer letting the family (especially the guardian) rather than the third party to assume the position of protecting patients’ rights and provide proxy consent. The main responsibility for seeking medical health and paying for healthcare bills for those who are mentally or physically ill always rests upon the family (Hu, Higgins, & Higgins, 2006). Usually it is not the individual who is consulted about his own hospitalization but his family (Pearson, 1992). Moreover, traditionally Chinese people are more concerned with patient’s rights to receive treatment as well as protecting the society from the harm of the individual (Pearson, 1992). These cultural attitudes will influence a psychiatrist’s decision to seek involuntary admission for patient who has no obvious risks. Thus, the guardian (or family member) will consent to admission and physical treatment not only for an incapacitous patient but also a capacitous adult patient in some situations.

These cultural influences can also be seen in the process of making proxy consent and inform consent. In the draft of the National Mental Health Law, only a family member, close relative or guardian, or policemen can make an application to the designated mental health facility for committing the patient. For patient has no family or guardian, it is the responsibility of civil affairs department and police to apply for detention. However, in our survey a considerable proportion of the responders admitted that they would accept the patient’s community agency or working unit to do so, too. The reason might be that for many years, these persons or organizations have played an important role in patient’s community rehabilitation project (Yip, 2006). When a patient has no guardian or close relative, these organizations will take the place of guardian (Hu, et al., 2006; Zhang, Yan, & Phillips, 1994). Thus psychiatrists are used to these traditions. Besides, 24.5% of the responders admitted that they would not informed patients and families about their rights in a written form at the time of admission also reflected a paternalistic attitude in some psychiatrists.

Third, one interesting finding in our survey is the different attitudes among responder subgroups. Female, low education level and low position are associated with stricter attitudes in the procedure of involuntary admission.

Previous study found that psychiatrists’ high risk-taking behaviors may be related to their decisions not to seek involuntary admission (Pirzada Sattar, Pinals, Din, & Appelbaum, 2006). Thus it seemed that male psychiatrist should more unwilling to seek involuntary admission since their higher risk-taking propensity compared to female (Hojat, & Zuckerman, 2008; Killgore, Grugle, Killgore, & Balkin, 2010). But in our research, on the contrary, female responders showed more cautious attitudes in seeking involuntary admission. Such difference of our findings with oversea study may be explained by the difference in understand risk-taking behavior. Due to the absence of legislation to standardize the clinical practice of psychiatrist in China (mainland), seeking involuntary admission for patient without obvious danger behavior or without proxy consent form guardian may cause the risk to be faced with a malpractice complaint. Such supposition was partly sustained by the association between arbitrary attitudes in admission and a history of expose to patient’s malpractice complaint in our research. While arbitrary attitudes in admission may enhance the risk of malpractice complaint, people with lower risk-taking propensity may more cautious in seeking involuntary admission.

The arbitrary attitudes of responders with high education level were more disobeying the provision of the National Mental Health Law (draft). Like Brooks’ (2006) finding that even the highly educated professionals showed strong preferences for what they believed to be the status quo. The reason may be the medical education in China is more focused on the clinical knowledge and research ability. Legal and ethnical issues were unweighted in such system. Thus high education level does not necessarily imply better knowledge of legitimate admission procedures.

Responders older than 35 or with higher position showed more arbitrarily attitudes in the admission process. This might be happening in correspondence with somewhat more conservative values of the older generations (Lepping, et al., 2004), and with the increase of age and working experiences, responders tended to use their discretions in making clinical decision. One possible reason may be that senior psychiatrists usually have to deal with more patients in outpatient clinics than junior ones so that the time spends on each patient decreased accordingly. In such situation, their concern about procedural requirements was much less and behaviors in admission procedure were substandard some time.

In our survey, responders from cities with mental health legislation showed more prudent attitudes about admission procedures, especially in qualification of proxy consent and process of inform consent. Multiple logistic regression analysis also found that legislation was a positive predictor of such prudential attitudes in admission procedures. We presume such relation can be explained in either of two ways. Since a person’s preferences are subject to influence through social interaction (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, & Welch, 1992), the relationship may be attributed to extant legislation in these cities. One important aim of the mental health legislation in China was designed as an initial effort to protect the rights of people diagnosed with mental illness and improve access to mental health services (Park, Xiao, Worth, & Park, 2005). Thus all these municipal mental health regulations have clear statutes about admission procedure. After mental health legislation was carried out in these cities, the relevant laws and rules on admission have subsequently been transformed by academic organizations and hospitals into ordinary practice guidelines. Responders appear to have internalized these norms when answering our questions. However, the association could also be due to a more subtle causal mechanism. The cities with legislations are often more “advanced” and open (e.g., regarding the acknowledgment of international standards) in Mainland China, so better attitudes toward protecting patients might had been present before the legislations were made.

Nevertheless, even the responders from cities with mental health legislation also showed quite a number of inappropriate attitudes. One potential reason may be the lack of detailed procedures regarding the implementation of these rules in these municipal statues (Shao, Xie, DelVecchio Good, & Good, 2010). The lack of specificity in these articles makes psychiatrists difficult to implement these requirements. More important, the presence of mental health legislation, however, does not in itself guarantee respect and protection of human rights (WHO, 2005). Just like Keski-Valkama’s research had showed that legislative changes solely in Finland cannot reduce the use of seclusion and restraint or change the prevailing treatment cultures connected with these measures (Keski-Valkama, Sailas, Eronen, Koivisto, Lönnqvist, & Kaltiala-Heino, 2007), those customs were deeply internalized by various psychiatrists and influences their attitudes and behaviors. After mental health legislation, it is difficulty for them to change their attitudess according to the reforms in law immediately. This implies that change caused by reform in law usually comes in pieces, not from whole cloth.

There are several limitations in this study which may make the results tentative. First, CPA members may not represent all professionals involved in psychiatric service in China. But just as we had mentioned before, their attitudes and behaviors have a significant impact on their colleagues. We believe their response can reflect the status quo in China to a certain degree. Second, there may be a tendency to answer according to standards rather than actual attitudes. However, at the very least there is no reason to assume that any of the subgroups would be more likely than others to misreport, so the comparisons are probably valid. Third, psychiatrists’ attitudes and beliefs may not directly translate into behaviors in daily work.

Despite above limitations, these findings still carry important messages to the administration of psychiatric institutions. Previous studies showed that stigmatization associated with mental illness and lack of trust in the services were major deterring factors which may prevent Chinese people from seeking psychiatric treatment in China (Boey, 1998; Tang, Sevigny, Mao, Jiang, & Cai, 2007). If psychiatrists have considerable arbitrary attitudes to the process of involuntary admission, things will be made even worse. Thus every effort needs to be made to minimize these attitudes to prevent negative outcomes. This might be done through peer review, supervision, and even some punitive measures in the practice of involuntary admission. For lawmakers in the field of mental health, these findings also have immense implications. The “law in books” and “law in practice” are sometimes rather different. Once legislation (weather at the municipal or national level) had been passed, it is necessary to provide specific training programs for medical and mental health professionals and staff. In these programs, issues regarding rights to treatment and the proper procedure of involuntary admission should be emphasized.

Conclusions

The findings of this research are preliminary, but this small sample of psychiatrists from CPA has produced data with significant implications. Further research is needed involving other Chinese psychiatrists and a more extensive evaluation of factors that could influence their attitudes and clinical practice. The results of this initial research imply that psychiatrists in China had considerable arbitrary attitudes to the procedure of involuntary admission. Such arbitrary attitudes were associated with many variables. Thus the task to protect the rights of people diagnosed with mental illness still has a long way to go.

Acknowledgments

This survey was partially supported by the “Investigation Funding of China Association for Science and Technology” (2007DCY112) and by the NIH Fogarty International Center grant (5 D43 TW05809) awarded to Byron J. Good, P.I., in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School.. We express our appreciation to Dr. Hsuan-Ying Huang for his role in editing this paper.

Contributor Information

Yang Shao, Email: sawyer2002@163.net.

Bin Xie, Email: binxie64@gmail.com.

Zhiguo Wu, Email: wu_zhiguo@yahoo.com.cn.

References

- Bikhchandani S, Hirshleifer D, Welch I. A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural changes as informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy. 1992;100:992–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Boey KW. Psychosocial factors associated with seeking psychiatric treatment: A study on adolescents in Shanghai. International Medical Journal. 1998;5(4):293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA. U.S. Psychiatrists’ beliefs and wants about involuntary civil commitment grounds. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2006;29:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA. Psychiatrists’ opinions about involuntary civil commitment: results of a national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2007;35:219–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojat M, Zuckerman M. Personality and specialty interest in medical students. Medical Teacher. 2008;30(4):400–406. doi: 10.1080/01421590802043835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Higgins J, Higgins LT. Development and limits to development of mental health services in China. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2006;16:69–76. doi: 10.1002/cbm.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keski-Valkama A, Sailas E, Eronen M, Koivisto AM, Lönnqvist J, Kaltiala-Heino R. A 15-year national follow-up: legislation is not enough to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:747–752. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Grugle NL, Killgore DB, Balkin TJ. Sex Differences in Self-Reported Risk-Taking Propensity on the Evaluation of Risks Scale. Psychological Reports. 2010;106(3):693–700. doi: 10.2466/pr0.106.3.693-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T, Wan X, Ip MS. Current perspectives on medical education in China. Medical Education. 2006;40(10):940–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepping P, Steinert T, Gebhardt RP, Röttgersc HR. Attitudes of mental health professionals and lay-people towards involuntary admission and treatment in England and Germany - a questionnaire analysis. European Psychiatry. 2004;19:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu Q, Ma Z. The Effect of Schizophrenia Patient and Their Families on Their Right of Knowing and Agreeing on the Facts of Hospitalization. Journal of Nursing (Chinese) 2006;13(6):4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Luchins DJ, Cooper AE, Hanrahan P, Rasinski K. Psychiatrists’ attitudes toward involuntary hospitalization. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:1058–1060. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health website. Chinese Health Statistical Digest 2009. 2005 http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjty/digest2009/T8/sheet022.htm.

- Pan Z, Xie B, Zheng Z. A survey on psychiatric hospital admission and relative factors in China. Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine (Chinese) 2003;13:270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Park L, Xiao Z, Worth J, Park J. Mental Health Care in China: Recent Changes and Future Challenges. Harvard Health Policy Review. 2005;6:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson V. Law, Rights, and Psychiatry in the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1992;15:409–423. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(92)90021-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirzada Sattar S, Pinals DA, Din AU, Appelbaum PS. To Commit or Not to Commit: The Psychiatry Resident as a Variable in Involuntary Commitment Decisions. Academic Psychiatry. 2006;30:191–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds TA, Tierney LM., Jr Medical education in modern China. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2141. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Peay J, Eastman N. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards legal compulsion: report of a National Survey. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2002;1:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Xie B, DelVecchio Good MJ, Good BJ. Current legislation on admission of mentally ill patients in China. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2010;33:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Sevigny R, Mao P, Jiang F, Cai Z. Help-seeking Behaviors of Chinese Patients with Schizophrenia Admitted to a Psychiatric Hospital. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Resource Book on Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation. WHO Press; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yip KS. An Historical Review of The Mental Health Services in the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2005;51:106–118. doi: 10.1177/0020764005056758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip KS. Community Mental Health in the People’s Republic of China: A Critical Analysis. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006;42:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Yan H, Phillips MR. Community-based psychiatric rehabilitation in Shanghai. Facilities, services, outcome, and culture-specific characteristics. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;165 (Supplement 24):70–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegenbein M, Anreis C, Brüggen B, Ohlmeier M, Kropp S. Possible criteria for inpatient psychiatric admissions: which patients are transferred from emergency services to inpatient psychiatric treatment? BMC Health Services Research. 2006;6:150. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]