Abstract

Aim

To better understand the impact of non-English language spoken in the home on measures of cognition, language, and behavior in toddlers born extremely preterm.

Methods

Eight hundred and fifty children born at <28 weeks gestational ages were studied. 427 male and 423 female participants from three racial/ethnic groups (White, Black, and Hispanic) were evaluated at 18-22 months adjusted age using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development 3rd edition and the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). Children whose primary language was Spanish (n=98) were compared with children whose primary language was English (n=752), using multivariable regression adjusted for medical and psychosocial factors.

Results

Cognitive scores were similar between groups; however, receptive, expressive and composite language scores were lower for children whose primary language was Spanish. These differences remained significant after adjustment for medical and socio-economic factors. Spanish speaking children scored worse on the BITSEA competence and problem scores using univariate analysis, but not after adjustment for medical and socio-economic factors.

Conclusions

Our finding that preterm children whose primary language was Spanish had similar cognitive but lower language scores than those whose primary language was English suggests that using English language-based testing tools may introduce bias against non-English speaking children born preterm.

Keywords: development, prematurity, second-language, race/ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

Children born extremely preterm are at increased risk for developmental and learning problems1,2,3, health impairments4, and early death5. While the pathogenesis of developmental delays in children born preterm is incompletely understood, factors in addition to medical issues, such as socio-economic disadvantage6, behavior problems7 and parenting behavior8, have been implicated. Bilingual environment has also been associated with lower mental developmental index (MDI) scores on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development second edition (BSID-II) at 2 years of age in very low birth weight infants.9 The newly revised Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, third edition (BSID-III),10,11 separates assessment of cognition from language, allowing specific exploration of the combination of prematurity and non-English speaking environment on cognition and language development.

Infant behavior and social emotional ability may be measured using the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). Previous studies have demonstrated that BITSEA scores indicating better social emotional functioning are associated with higher BSID language scores in toddlers born at term gestation12. Because social, emotional, and behavioral functioning have been linked with language ability, utilization of behavioral measures such as the BITSEA could delineate useful behavioral targets for interventions benefitting language development. This is unknown, however, because most previous studies have examined only term-born, English-speaking children. It is possible that assessment of social emotional and language ability without consideration of native language spoken in the home may limit developmental test interpretation in preterm children.

The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between primary language spoken in the home and developmental testing in areas of cognition, language, and behavior among children born extremely preterm (≤28 weeks gestation) at 18 to 22 months corrected age. Our comparison was limited to those who identified English or Spanish as the primary language spoken in the home because of the extremely small sample sizes for other languages. All children in this study were living in the United States, though some parents were immigrants from Spanish speaking countries. We hypothesized that those children who spoke Spanish as their primary language would have: (1) lower scores on the BSID-III cognitive and language scales; (2) lower scores on the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA) problem and competence scores.

METHODS

Participants

This study was an ancillary to a larger randomized trial of inborn infants born at <28 weeks gestation at the sixteen centers of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network (NRN) who had a developmental evaluation at 18 to 22 months adjusted age between January 2008 and June 2009. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all sites. Primary caregivers gave informed written consent to the research prior to participation. Race and ethnicity were defined by parental report. Children were excluded if race/ethnicity data were missing, if they belonged to a racial/ethnic group with ≤ 30 children, if there were missing BSID-III scores, or if the child had a major congenital syndrome or anomaly.

Of 914 children seen in follow-up during this period, 370 were White, 356 Black, 148 Hispanic, 19 Asian, 1 Native American, and 20 had missing race and/or ethnicity. After exclusion of the racial/ethnic groups with less than 30 children and children with primary languages other than English or Spanish, 850 children remained for analysis, of whom 752 were in English speaking homes and 98 were in Spanish speaking homes. Of the 98 children with Spanish as their primary language in the home, 94 were Hispanic, 3 were White and 1 was Black (67%, 0.8% and 0.3%, of the analysis population for each ethnicity, respectively). Four children designated as Hispanic-black spoke Spanish in the home and were included in the Hispanic category rather than the black.

Developmental Scales

The Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) were developed and standardized in English and remain one of the most widely used measures of development in infants and toddlers10. The third edition of the BSID (BSID-III) has separate scales for cognition and language, which allows separate evaluation of the impact of administering this English-based test on cognitive and language scores in non-English speaking children11.

All children were evaluated by NRN-certified examiners using the BSID-III cognitive and language scales. For children whose primary language was identified as Spanish, the BSID-III was translated and administered in Spanish by either a bilingual examiner or a certified examiner with an interpreter.

The Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment13 (BITSEA) is a parent-report questionnaire assessing social/emotional difficulties in children ages 12 to 36 months. Parents rate the individual questions on a Likert scale from 0 to 2 for 49 problem scale items and 11 competence scale items. Scales include measures of externalizing behaviors (activity, aggression), internalizing behaviors (inhibition, depression), dysregulation (problems sleeping, eating), maladaptive habits, fears, and competence (attention, compliance). A standardized score is obtained for the problem and competence scales. The BITSEA questionnaire was translated into Spanish, although standardization was performed with English speaking parents and their children, as with the BSID.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics of the Spanish and English speaking groups were compared using chi-square tests for categorical characteristics and t-tests for continuous characteristics. Measured outcome variables included BSID-III cognitive score, composite language score, expressive language score, receptive language score, and the BITSEA competence and problem scales. Spanish primary language was the independent variable. Both BSID-III and BITSEA scores for Spanish and English speaking groups were compared using general linear regression models with and without adjusting for medical and psychosocial factors previously shown to adversely impact neurodevelopmental outcomes in at-risk children14, 15. Factors included as covariates were: gestational age, small for gestational age (SGA), multiple gestation, antenatal steroid use, postnatal steroid use, Grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), culture-proven late onset sepsis treated with greater than 5 days of antibiotics, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) defined as need for supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks gestation, visual or hearing impairment reported at 18-22 month follow up exam, adjusted age at testing, gender, maternal age, parity, primary caretaker education and birth center.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics for the study population by primary language are presented in Table 1. The Spanish speaking children were younger than the English speaking children, had mothers with higher parity, and had primary caretakers with less education.

Table I.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics by Primary Language for All Subjects

| English (N=752) | Spanish (N=98) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted age for BSID-III cognitive subscale (months) | Mean (StdDev) | 19.7 (1.4) | 19.4 (1.2) | 0.04 |

| SGA | % | 5.0 | 2.0 | 0.19 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | Mean (StdDev) | 25.4 (1.2) | 25.4 (1.1) | 0.58 |

| Gender | Female: % | 50.4 | 44.9 | 0.31 |

| Male: % | 49.6 | 55.1 | ||

| Maternal age (years) | Mean (StdDev) | 27.2 (6.6) | 27.8 (6.2) | 0.44 |

| Multiple gestation | % | 27.9 | 21.4 | 0.17 |

| Parity | Mean (StdDev) | 2.2 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.5) | 0.04 |

| Primary caretaker education | < High school degree: % | 15.0 | 59.6 | <.001 |

| High school degree: % | 28.3 | 21.4 | ||

| Partial college: % | 30.2 | 11.2 | ||

| >/= College degree: % | 26.5 | 7.9 | ||

| Antenatal steroids | % | 87.5 | 80.4 | 0.05 |

| BPD | % | 50.6 | 42.3 | 0.12 |

| Postnatal steroids | % | 12.7 | 9.2 | 0.32 |

| Grade III or IV IVH | % | 13.4 | 15.5 | 0.57 |

| Cystic PVL | % | 5.0 | 4.1 | 0.68 |

| Nosocomial sepsis | % | 39.1 | 40.8 | 0.74 |

| Visual Impairment | % | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.93 |

| Hearing Impaired | % | 3.5 | 3.1 | 0.84 |

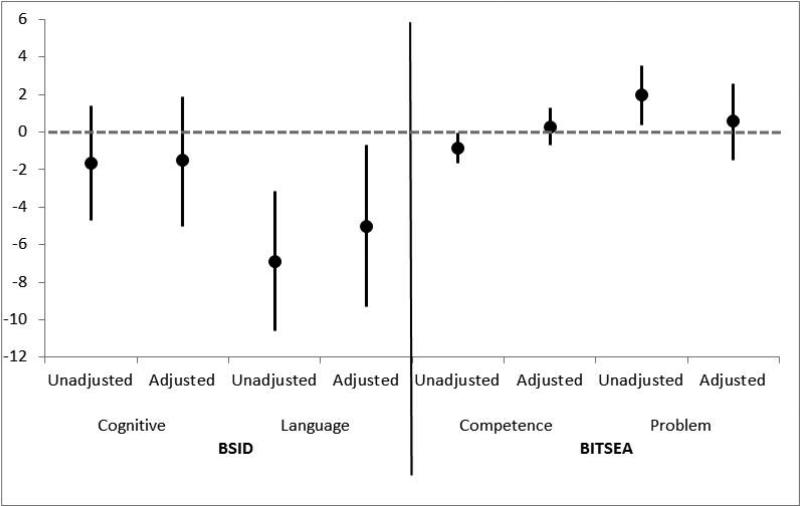

The unadjusted and adjusted comparisons of the study outcomes of English and Spanish speaking children are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. There was no significant difference in BSID-III cognitive scores between Spanish and English-speaking children in both unadjusted or adjusted analysis. However, language scores were significantly lower for the Spanish-speaking children. These differences persisted after adjustment for medical and socio-economic factors.

Table II.

Association of Primary Language with BSID III and BITSEA Scores

| English (N=752) | Spanish (N=98) | P-value [1] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSID-III | |||

| Cognitive | |||

| Median [25-75%] | 90 [80-100] | 90 [80-95] | |

| Mean (StdDev) | 90.0 (14.8) | 88.3 (12.9) | 0.29 |

| Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | −1.5 (−5.0,1.9) | 0.38 | |

| Language | |||

| Median [25-75%] | 86 [74-97] | 77 [71-86] | |

| Mean (StdDev) | 85.6 (17.5) | 78.7 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | −5.0 (−9.3,−0.7) | 0.02 | |

| Expressive | |||

| Median [25-75%] | 8 [6-10] | 7 [5-8] | |

| Mean (StdDev) | 7.8 (2.9) | 6.8 (2.4) | <0.01 |

| Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | −0.9 (−1.7,−0.1) | 0.03 | |

| Receptive | |||

| Median [25-75%] | 8 [6-10] | 6 [5-8] | |

| Mean (StdDev) | 7.7 (2.9) | 6.1 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | −0.8 (−1.5,−0.0) | 0.05 | |

| BITSEA | |||

| Competence | |||

| Median [25-75%] | 17 [15-20] | 16 [14-18] | |

| Mean (StdDev) | 16.7 (3.6) | 15.8 (3.4) | 0.04 |

| Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | 0.3 (−0.7,1.3) | 0.59 | |

| Problem | |||

| Median [25-75%] | 11 [6-16] | 13 [7-18] | |

| Mean (StdDev) | 11.7 (7.0) | 13.6 (7.4) | 0.01 |

| Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | 0.6 (−1.5,2.6) | 0.57 |

[1] P-values for ‘Mean (StdDev)’ rows obtained from a t-test. Adjusted mean differences and the corresponding p-values obtained from a regression model with the score of interest as the outcome, primary language as the explanatory variable and controlling for medical and socioeconomic factors. Adjusted mean differences are calculated as the difference of the Spanish as a primary language group compared to the English as a primary language group.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted and adjusted mean differences and associated 95% CIs for BSID-III and BISTEA Scales. Adjusted mean differences are obtained from a regression model with the score of interest as the outcome, primary language as the explanatory variable and controlling for all medical and socioeconomic factors. Adjusted mean differences are calculated as the difference of the Spanish as a primary language group compared to the English as a primary language group.

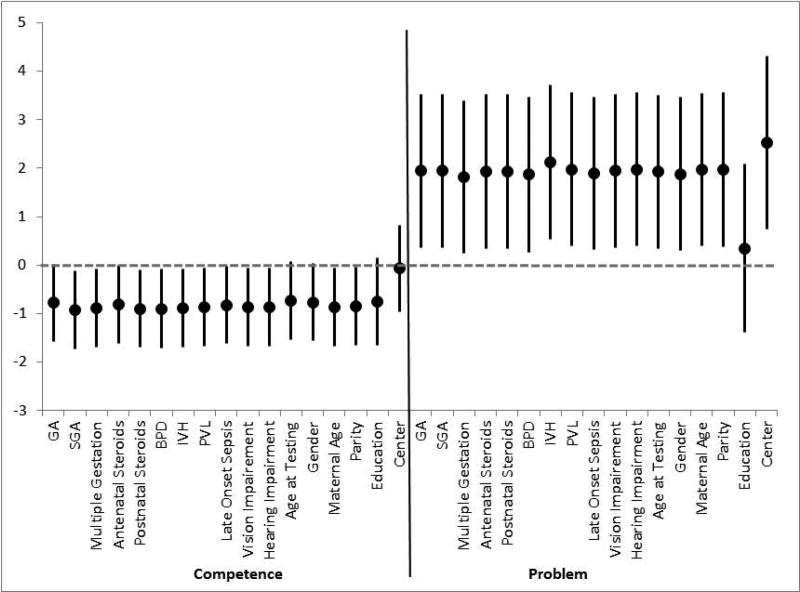

Spanish-speaking children scored significantly worse on the BITSEA competence and problem scales in the unadjusted analyses. These differences were no longer significant after adjustment for medical and socio-economic covariates. When adjusting individuals for each covariate, the difference in competence scales is no longer significant after adjusting for GA, age at testing, gender, primary caregiver education or birth center. Difference in problem scale is no longer significant after adjusting for primary caregiver education (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that children who had Spanish as the primary language in their home had significantly lower language scores on the BSID-III than children with English as their primary language; this difference remained, even after adjustment for medical and socio-economic covariates. In contrast, we found no significant differences in cognitive scores between English and Spanish-speaking groups. While BITSEA scores were lower for Spanish-speaking children on univariate analysis, this difference was eliminated when medical and psychosocial factors were added to the model.

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association of primary language with cognitive, language and behavioral outcomes of children born extremely preterm. One other study has reported significantly lower BSID-II Mental Developmental Index (MDI) scores in very low birth weight infants with bilingual parents, unexplained by socioeconomic factors 9. Those authors hypothesized that the additional input of a second language could have negatively affected overall development, due to the demands of learning two languages; however, the separation of cognition from language on the BSID-III now allows separate evaluation of these domains. Because we found no difference in the cognitive scores, we speculate that the previously reported difference in BSID-II Mental Developmental Index for bilingual children resulted from the language items contained within the MDI score.

Although in our study significantly more of the Spanish speaking primary caretakers compared to those who spoke English did not graduate High School, cognition was not different in the two groups and differences in language development were maintained even when primary caretaker education was accounted for as a socio-economic variable. Studies of bilingual children born at term have yielded results consistent with our findings. One study found that bilingual children performed less well on language portions of neuropsychological assessments at 6 and 7 years, but comparably on tests of attention and executive function16. Other studies have shown that bilingual children performed better on spatial tasks17 and tests of impulse control18, possibly because language is not required in those tests.

The Bayley Scales were developed and standardized in English, and there is no standardized Spanish version. Despite that, the BSID-III is translated at the time of administration and administered to children who speak different languages because there is no published non-English based standardized test for this age group. Our study highlights the potential hazard of this practice for interpreting neurodevelopmental testing. We speculate that the language scale of the BSID-III is altered when administered in another language because of differences in translation, the varying Spanish dialects spoken regionally, and the Spanish language structure. For example, many words used in testing are monosyllabic in English but multi-syllabic in Spanish (e.g. “ball” versus “pelota”; “doll” versus “muñeca”). Mothers in different ethnic groups have been found to use different language and gestures to communicate with their children19, which may affect BSID-III language scores. Though the children were predominantly Spanish speaking, they were living in English speaking communities and the exposure to two languages could have contributed to overall language delays20.

BITSEA problem and competence scores were significantly different between the groups in the unadjusted analysis but not when primary caregiver education was added to the model. It is possible that education level impacted the primary caregiver's ability to understand the questions. BITSEA competence score has been found to be correlated with developmental level13, and this association could also be impacted by primary caregiver education which has been related to lower cognition in preterm children1,3. In addition, the addition of birth center to the analysis eliminated the significant differences in the BITSEA competence scores, which might indicate that center is a proxy for SES.

One limitation of our study is the use of self-report as the method of identifying race and ethnicity. Though self-report remains one of the most reliable methods of collecting this information, 21 there still remains an unknown risk of error. In addition, although we adjusted for medical and socioeconomic factors known to affect developmental outcomes, we recognize that additional unknown confounders, such as the amount of Spanish or English used in the home, type or amount of daycare, or possibly even different attitudes of examiners toward Spanish-speaking children may have affected results. A major strength of this study is the large data set and the diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds of children in the Neonatal Research Network, which allowed us to study for the first time the impact of non-English primary language on developmental testing of children 21 born extremely preterm.

In conclusion, we found that children born extremely preterm living in non-English speaking homes performed less well on tests of language development. Although we performed this study with children born extremely preterm, the testing bias introduced by differences in primary language may well hold true in children born at term gestation, and should be studied in that population also. We urge caution in interpreting tests of development normed in English, when used with young children from non-English speaking homes. Alternate ways of measuring language skills, such as free play paradigms, could be useful22 when assessing language development in children from non-English speaking homes. Culturally appropriate ways to evaluate children from non-English speaking homes should be further explored with the goal of providing more effective intervention strategies.

Key Notes.

Non-English speaking children born preterm scored more poorly on tests of receptive and expressive language. Lower scores on tests of language persisted even when medical and socio-economic factors were considered. Accounting for a preterm child's primary language is important when testing and interpreting developmental outcome.

Figure 2.

Mean differences and associated 95% CIs for BISTEA Scales after adjusting individual for each medical and socioeconomic factor. Adjusted mean differences are obtained from a regression model with the score of interest as the outcome, primary language as the explanatory variable and controlling individual for each medical and socioeconomic factor. Adjusted mean differences are calculated as the difference of the Spanish as a primary language group compared to the English as a primary language group.

Acknowledgements

The National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network's Generic Database and Follow-up Studies.

Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN) were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, Dr. Abhik Das (DCC Principal Investigator) and Ms. Tracy Nolen (DCC Statistician) had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

NRN Steering Committee Chair: Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine.

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, RN BSN; Robert Burke, MD; Melinda Caskey, MD; Katharine Johnson, MD; Barbara Alksninis, PNP; Dawn Andrews, RN MS; Kristen Angela, RN; Theresa M. Leach, MEd CAES; Victoria E. Watson, MS CAS; Suzy Ventura.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80) – Michele C. Walsh, MD MS; Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Nancy S. Newman, BA RN; Bonnie S. Siner, RN; Monika Bhola, MD; Gulgun Yalcinkaya, MD; Harriet G. Friedman, MA.

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, University Hospital, and Good Samaritan Hospital (U10 HD27853, M01 RR8084) – Kurt Schibler, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Kate Bridges, MD; Barbara Alexander, RN; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Holly L. Mincey, RN BSN; Jody Hessling, RN; Teresa L. Gratton, PA; Jean J. Steichen, MD; Kimberly Yolton, PhD.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, Alamance Regional Medical Center, and Durham Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, M01 RR30) – Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN MSN.

Emory University, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (U10 HD27851, M01 RR39) – Barbara J. Stoll, MD; David P. Carlton, MD; Ellen C. Hale, RN BS CCRC; Maureen Mulligan LaRossa, RN; Irma Seabrook, RRT; Gloria V. Smikle, PNP MSN.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Rosemary D. Higgins, MD; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750) – Brenda B. Poindexter, MD MS; Anna M. Dusick, MD; Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN CCRC; Faithe Hamer, BS; Carolyn Lytle, MD MPH; Heike M. Minnich, PsyD HSPP.

RTI International (U10 HD36790) – W. Kenneth Poole, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Jamie E. Newman, PhD MPH; Jeanette O'Donnell Auman, BS; Margaret Cunningham, BS; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS; Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN BSN.

Stanford University, Dominican Hospital, El Camino Hospital, and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital (U10 HD27880, M01 RR70) – Krisa P. Van Meurs, MD; David K. Stevenson, MD; Susan R. Hintz, MD MS Epi; Alexis S. Davis, MD MS Epi; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Andrew W. Palmquist, RN; Melinda S. Proud, RCP; Elizabeth Bruno, PhD; Maria Elena DeAnda, PhD; Anne M. DeBattista, RN PNP; Jean G. Kohn, MD MPH; Hali E.Weiss, MD.

Tufts Medical Center, Floating Hospital for Children (U10 HD53119, M01 RR54) – Ivan D. Frantz III, MD; John M. Fiascone, MD; Brenda L. MacKinnon, RNC; Anne Furey, MPH; Ellen Nylen, RN BSN; Elisabeth C. McGowan, MD.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children's Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN; Fred J. Biasini, PhD; Kristen C. Johnston, MSN CRNP; Kathleen G. Nelson, MD; Cryshelle S. Patterson, PhD; Vivien A. Phillips, RN BSN; Sally Whitley, MA OTR-L FAOTA.

University of California – San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women and Newborns (U10 HD40461) – Neil N. Finer, MD; Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD MPH; David Kaegi, MD; Maynard R. Rasmussen, MD; David Kaegi, MD; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Clarence Demetrio, RN; Martha G. Fuller, RN MSN; Chris Henderson, RCP CRTT; Wade Rich, BSHS RRT; Radmila West PhD.

University of Iowa, Children's Hospital (U10 HD53109, M01 RR59) – Edward F. Bell, MD; Michael J. Acarregui, MD; Karen J. Johnson, RN BSN; Diane L. Eastman, RN CPNP MA.

University of Miami, Holtz Children's Hospital (U10 HD21397, M01 RR16587) – Shahnaz Duara, MD; Charles R. Bauer, MD; Ruth Everett-Thomas, RN MSN; Sylvia Hiriart-Fajardo, MD; Maria Calejo, MS; Silvia M. Frade Eguaras, MA; Michelle Harwood Berkowits, PhD; Andrea Garcia, MA; Helina Pierre, BA; Alexandra Stoerger, BA.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (U10 HD53089, M01 RR997) –Robin K. Ohls, MD; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN; Rebecca Montman, BSN. University of Rochester Medical Center, Golisano Children's Hospital (U10 HD40521, UL1 RR24160, M01 RR44) – Dale L. Phelps, MD; Gary J. Myers, MD; Linda J. Reubens, RN CCRC; Erica Burnell, RN; Diane Hust, MS RN CS; Julie Babish Johnson, MSW; Rosemary L. Jensen; Emily Kushner, MA; Joan Merzbach, LMSW; Kelley Yost, PhD; Lauren Zwetsch, RN MS PNP.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Medical School, Children's Memorial Hermann Hospital, and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District (U10 HD21373) – Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Nora I. Alaniz, BS; Patricia W. Evans, MD; Charles Green, PhD; Beverly Foley Harris, RN BSN; Margarita Jiminez, MD MPH; Anna E. Lis, RN BSN; Sarah Martin, RN BSN; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Brenda H. Morris, MD; M. Layne Poundstone, RN BSN; Saba Siddiki, MD; Maegan C. Simmons, RN; Patti L. Pierce Tate, RCP; Sharon L. Wright, MT(ASCP).

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System, and Children's Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633) – Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Alicia Guzman; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Sally S. Adams, MS RN CPNP; Linda A. Madden, RN CPNP; Elizabeth Heyne, PsyD PA-C; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Catherine Twell Boatman, MS CIMI; Lizette E. Torres, RN.

University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, and Primary Children's Medical Center (U10 HD53124, M01 RR64, UL1 RR25764) – Roger G. Faix, MD; Bradley A. Yoder, MD; Karen A. Osborne, RN BSN CCRC; Cynthia Spencer, RNC; Kimberlee Weaver-Lewis, RN BSN; Shawna Baker, RN; Jill Burnett, RNC; Mike Steffen, PhD.

Wake Forest University, Baptist Medical Center, Forsyth Medical Center, and Brenner Children's Hospital (U10 HD40498, M01 RR7122) – T. Michael O'Shea, MD MPH; Robert G. Dillard, MD; Lisa K. Washburn, MD; Barbara G. Jackson, RN, BSN; Nancy Peters, RN.

Wayne State University, Hutzel Women's Hospital and Children's Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385) Seetha Shankaran, MD; Athina Pappas, MD; Rebecca Bara, RN BSN; Laura A. Goldston, MA.

Yale University, Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital, and Bridgeport Hospital (U10 HD27871, UL1 RR24139, M01 RR125) – Harris Jacobs, MD; Christine G. Butler, MD; Patricia Cervone, RN; Sheila Greisman, RN; Monica Konstantino, RN BSN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Janet Taft, RN BSN; Joanne Williams, RN BSN; Elaine Romano, MSN.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BSID-II

Bayley Scales of Infant Development 2nd edition

- BSID-III

Bayley Scales of Infant Development 3rd edition

- BITSEA

Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment

- MDI

Mental Developmental Index

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors have any conflict of interest or disclosure of any professional affiliations, financial agreements or other involvements with any company. The authors wrote the first draft of the paper and no honorariums, grants or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pritchard VE, Clark CA, Liberty K, Champion PR, Wilson K, Woodward LJ. Early school-based learning difficulties in children born very preterm. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll B, et al. Neonatal outcome of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126:443–456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, Perritt R, Poole WK, Tyson JE, et al. Center differences and outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2004;113:781–789. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massett HA, Greenup M, Ryan CE, Staples DA, Green NS, Mailbach EW. Public perception about prematurity. A national survey. Am j Prev Med. 2003;24:120–127. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, Green C, Higgins RD. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Intensive care for extreme prematurity: moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1672–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus BM, Carle AC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Ganz M, Hauser-Cram P, McCormick MC. Social determinant of state variation in special education participation among preschoolers with developmental delay and disabilities. Health & Place. 2011;17:681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray RF, Indurkhya A, McCormick M. Prevalence, stability and predictors of clinically significant behavior problems in low birth weight children at 3, 4 and 7 years of age. Pediatrics. 2004;114:736–743. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1150-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treyvaud K, Anderson VA, Howard K, Bear M, Hunt RW, Doyle LW, Inder TE, Woodward L, Anderson PJ. Parenting behavior is associated with the early neurobehavioral development of very preterm children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:555–561. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walch E, Chaudhary T, Herold B, Obladen M. Parental bilingualism is associated with slower cognitive development in very low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aylward GP. Developmental screening and assessment: what are we thinking? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:169–173. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31819f1c3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayley N. Bayley Scale of Infant and Toddler Development 3rd edition. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spieker S, Nelson EM, Condon MC. Validity of the TAS-45 as a measure of toddler-parent attachment:Preliminary evidence from Early Head Start families. Hum Dev. 2011;13:69–90. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2010.488124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assesment (BITSEA) manual, version 2.0. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papile LA, Bursteing J, Bursteing R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage : a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 grams. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt B, Asztalos EV, Roberts RS, Sauve RS, Whitfield MF. Impact of bronchopulmonary dysplasic, brain injury and severe retinopathy on the outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants at 18 months. JAMA. 2003;280:1124–1129. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garratt LC, Kelly TP. To what extent does bilingualism affect children's performance on the NEPSY? Child Neuropsycho. 2008;14:71–81. doi: 10.1080/09297040701218405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garratt LC, Kelly TP. To what extent does bilingualism affect children's performance on the NEPSY? Child Neuropsycho. 2008;14:71–81. doi: 10.1080/09297040701218405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLeay H. The relationships between bilingualism and performance of spatial task. Intern J of Educ and Bilingualism. 2003;121:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamis-LeMonda C, Song L, Leavell A, Kahana-Kalman R, Yoshikawa H. Ethnic differences in mother–infant language and gestural communications are associated with specific skills in infants. DevSci. 2012;15:384–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Páez MM, Tabors PO, López LM. Dual language and literacy development of Spanish-speaking preschool children. J App Dev Psy. 2007;28:85–102. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egede LE. Race, ethnicity, culture, and disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:667–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.0512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz LE, Bonawitz EB. Serious fun: Preschoolers engage in more exploratory play when evidence is confounded. Dev Psy. 2007;43:1045–1050. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]