Abstract

The antioxidant activity of thuja (Thuja occidentalis) cones extract (TCE) and peach (Prunus armeniaca) seeds extract (PSE) were estimated by DPPH free radical scavenging activity method. Total phenolics, total flavonoids and reducing power were also estimated in these extracts. Antioxidant potential of these by products was also evaluated in raw chicken ground meat (GM) during refrigerated (4 ± 1 °C) storage. Total phenolics in TCE and PSE were 7.80 ± 0.04 and 1.92 ± 0.04 mg TAE/gdw respectively. Both extract also showed remarkable DPPH radical scavenging activity (25.52 ± 1.92% and 24.99 ± 0.32%). The reducing powerOD700 was observed more in TCE as compared to PSE (3.32 ± 0.01 and 0.49 ± 0.01). Total flavonoids contents were 7.48 ± 0.02 and 0.85 ± 0.01 mg CE/gdw respectively. Addition of these extract significantly (P < 0.01) affected cooking losses and WHC of GM. During refrigerated storage (4 °C) the TBARS values at 8 d were significantly (P < 0.01) more in control than TCE and PSE treated groups.

Keywords: Thuja, Peach, Antioxidant activity, DPPH, Reducing power, Meat, Lipid oxidation, TBARs

Introduction

The increasing inclination towards natural foods has obliged the food industry to include natural antioxidants in various products to delay oxidative degradation of lipids, improve quality and nutritional value of foods, and replace synthetic antioxidants (Fasseas et al. 2007; Wojdylo et al. 2007; Camo et al. 2008). Including antioxidants in the diet also has beneficial effects on human health because they protect the biologically important cellular components, such as DNA, proteins, and membrane lipids, from reactive oxygen species (ROS) attacks (Su et al. 2007). Consumers have rejected many synthetic antioxidants because of their carcinogenicity (Altmann et al. 1986). The advantages of natural antioxidants in foods are high consumer acceptance due to these health issues.

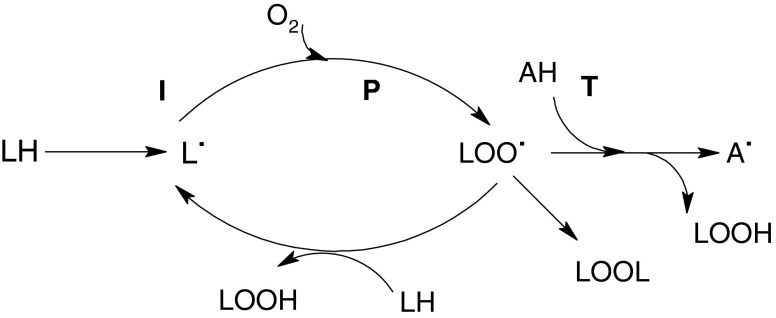

In general, fruits and plant by products are known to contain a wide variety of phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, carotenoids and vitamins. More than 5000 individual phytochemicals have been identified in fruits, vegetables, and grains (Liu 2003). Some of these contribute to the antioxidant potential of fruits and plant by products. Ascorbic acid and phenolics are known as hydrophilic antioxidants, whereas carotenoids are known as lipophilic antioxidants (Halliwell 1996). Oxidative stress caused by free radicals is involved in the aetiology of a wide range of chronic diseases. This happens because free radicals are chemically highly reactive and could cause oxidative damage to important cellular macromolecules, such as nucleic acids, proteins and lipids (Fig. 1). Thus, the natural antioxidants present in fruits and vegetables could scavenge free radicals and provide oxidative stability to many food items including high fat meat products (Yogesh et al. 2012).

Fig. 1.

Auto oxidation reactions (I, P and T = initiation, propagation and termination respectively) of polyunsaturated fatty acids, LH = unsaturated fatty acid; LOO. = peroxyl radicals; AH = antioxidant (free radical scavenger; chain breaking inhibitors); A. =scavenger radical (relatively very stable). [Polyphenols are very active in this respect and the radical-scavenging activities of gallates, nordihydroguairetic acid and flavonoids arise from this process]

Thuja occidentalis, commonly known as Arbor vitae or white cedar contains polyphenols, Coumarins, flavonoids, catechins etc, in large quantity which possesses many pharmaceutical, pharmacological and clinical Properties (Naser et al. 2005). Likewise the fresh Prunus persia (peach) fruit contains carbohydrates, vitamins C and K, β-carotene, niacin, and thiamine. Organic acids, phenols, volatile compounds, esters, and terpenoids have also been isolated (Ruiz et al. 2006).

There is no report of use of thuja (Thuja occidentalis) cones and peach (Prunus persia) seeds as a source of natural antioxidants in meat products to reduce oxidative damage and to increase product storage quality. The short shelf-life of refrigerated packed minced meat makes its commercialization more difficult. Some studies have demonstrated that meat shelf-life and quality can be improved by natural antioxidants and antimicrobials added in the pre-slaughter and post-slaughter stages. Currently, the interest in natural antioxidants has increased because they are considered to be safer than the synthetic antioxidants, and have greater application potential for consumers' acceptability, palatability, stability and shelf-life of meat products (Kang et al. 2008; Naveena et al. 2008; Park and Kim 2008).

Therefore in view of the presence of many polyphenols, antioxidant compounds and flavonoids in thuja cones and peach seeds which may contributes to antioxidant activity to these byproducts the main objective of this study was to determine the antioxidant efficacy of aqueous extract of these byproducts powder and to study the effect of these extract on cooking loss and water holding capacity with color and oxidative properties of chicken breast minced meat during 8 day refrigerated storage period.

Materials & methods

Materials

Different ingredients like peach and chicken breast meat (6 week of age) obtained from local market. The thuja cones obtained from local gardens of Ludhiana. All reagents and solvents were purchased from Merck and Sigma unless otherwise mentioned. TBA was obtained from MP Biomedicals, LLC. All chemicals used in the experiments were of analytical grade.

Preparation of aqueous solution of plant by products

Seeds were removed from Peach fruits and cones were separated from thuja twigs. Both by products dried in hot air oven at 45 °C for 48 h. Powder was made in heavy duty kitchen grinder and this obtained powder was sieved through 0.6 mm mesh size sieve. About 10 g of each powder was mixed with 200 ml boiled (50 μg/ml) sterilized distilled water and left for 2 h with frequent stirring. This was centrifuged at 5000 RPM for 10 min; the supernatant called as aqueous extract and was collected in another sterile tube and stored at 4 °C.

Treatment of chicken breast meat with extracts

Chicken breast meat was minced through mincer (8 mm plate). In group 1 one Kg minced meat grinded with 20 g salt, 50 ml ice cold thuja cone extract (TCE) and 50 ml vegetable oil for 5 min in a kitchen grinder, in group 2, 50 ml TCE was replaced with 50 ml peach seed extract (PSE) whereas in control samples 50 ml extract was replaced with 50 ml distilled water keeping other contents same as that of treated samples. These all treated and control ground meat (GM) were then filled in LDPE and stored at 4 °C for further studies.

Total phenolics

The concentration of total phenolics in extract was determined by the Folin- Ciocalteus (F-C) assay (Escarpa and Gonzalez 2001) with slight modifications. Suitable aliquots of extracts were taken in a test tube and the volume was made to 0.5 ml with distilled water followed by the addition of 0.25 ml F-C (1 N) reagent and 1.25 ml sodium carbonate solution (20%). The tubes were vortexed and the absorbance recorded at 725 nm after 40 min. The values were reported as mg of tannic acid equivalent (TAE) by reference to tannic acid standard curve and the results were expressed as milligrams of TAE per gram dry weight (gdw) of powder.

Measurement of reducing power

The reducing power was quantified by the method described by Jayaprakasha et al. (2001). The 2.5 ml extract was mixed with 2.5 ml phosphate buffer (200 μM, pH 6.6) and incubated with 2.5 ml potassium ferricyanide (1% w/v) at 50 °C for 20 min. At the end of incubation, 2.5 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid solution was added and centrifuged at 9700 g for 10 min. The 5 ml supernatant was mixed with 5 ml distilled water and 1 ml ferric chloride (0.1% w/v) solution. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm. Increase in absorbance of the reaction indicated increase in the reducing power of the extract.

Flavonoid content

Total flavonoid content of the extract was determined according to colorimetric method described by Zhishen et al. (1999), with some modification. Briefly 0.5 ml extract (1 mg/ml) was mixed with 2 ml of distilled water. Subsequently add 0.15 ml of sodium nitrite (NaNO2, 5% w/v) into each and the reaction mixture was allowed to stand for 6 min. Then 0.15 ml aluminium trichloride (AlCl3, 10%) was added and allowed to stand for 6 min, followed by addition of 2 ml of sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 4% w/v) to the reaction mixture. Then distilled water was added to the mixture to bring the final volume up to 5 ml, the reaction mixture was mixed thoroughly and allowed to stand for another 15 min. Then absorbance of pink colour developed was measured at 510 nm using spectrophotometer (UV-1800 PharmaSpec, SHIMADZU, Japan). Distilled water was used as blank.

The final absorbance of each sample was compared with a standard curve plotted from catechin. The total flavonoid content was expressed in mg of catechin equivalent per gram of dried powder (mg CE/gdw).

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The method of Singh et al. (2002) was employed to assess the ability of extracts to scavenge 1, 1-diphenyl 1-2- picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals; with slight modification. The 400 μl extract diluted with 1600 μl, 0.1 M Tris-HCI buffer (pH 7.4) was mixed with 2 ml of DPPH (500 μM) with vigorous shaking. The reaction mixture was stored in the dark at room temperature for 20 min and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm, the scavenging activity (SA) was calculated by the following equation:

|

Determination cooking loss and WHC

Water holding capacity (WHC) was determined according to Wardlaw et al. (1973). For cooking loss determination 20 g sample was sealed in a plastic bag and cooked in a water bath at 100° c for 20 min. Each piece was cooled, removed from the bag and then weighed. The weights of samples were recorded before and after cooking and the cook loss was expressed as a percentage (Yogesh et al. 2012).

Instrumental colour

Colour measurement was conducted on the surface of samples from d0 to d8 at 2 day intervals with a miniscan XE plus (Hunter Associated Labs, Inc, Reston, VA, USA) that had been calibrated against black and white reference tiles (X = 78.6, Y = 83.4, Z = 89.0). An average value from 4 random locations from duplicate sample surface was taken.

Estimation of oxidative stability

The thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) were determined from d 0 to d 8 by using the extraction method described by Witte et al. (1970) with slight modification. Four gm sample was homogenized with 20% trichloro acetic acid solution (20 ml) and the slurry was centrifuged at 3000 g (MP 400R Eltek Ltd., India) for 10 min. 2 ml of supernatant was mixed with equal volume of freshly prepared 0.1% thiobarbituric acid in glass test tubes and heated in water bath 100°c for 30 min followed by cooling under tap water. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 532 nm using UV–VIS spectrophotometer (UV-1800 PharmaSpec, SHIMADZU, Japan) and the TBARS values were calculated using a TBA standard curve and expressed in mg malonaldehyde/kg.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were done in triplicate with three measurement unless otherwise mentioned and results obtained were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and to Duncan’s multiple range procedure to determine the significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05).

Results and discussion

Total phenolics

Total phenolics in TCE and PSE examined in this study were 7.80 ± 0.04 and 1.92 ± 0.04 mg TAE/gdw respectively (Table 1). It is possible that the pigments like anthocyanin or other appreciable water soluble compounds contributed significantly to the total phenolics in these extract. Phenols are very important plant constituents because of their scavenging ability due to their hydroxyl groups. In the ethanolic fraction of thuja occidentalis 123 μg/ml, pyrocatechol equivalents to phenols were reported by Dubey and Batra (2009). The phenolic compound may contribute directly to the anti oxidative action (Hatano et al. 1989). Phenolic compounds are also effective hydrogen donors, which makes them good antioxidants (Rice-Evans et al. 1995).

Table 1.

Total phenolics (TP), total flavonoids (TF), Reducing power (RPOD700) and%DPPH radical scavenging activity of TCE and PSE

| Extract (50 mg/ml) | TP mg TAE/gdw | TF mg CE/gdw | RPOD700 | %DPPH SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCE | 7.8 ± 0.04 | 7.5 ± 0.02 | 3.3 ± 0.01 | 25.5 ± 1.92 |

| PSE | 1.9 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 24.9 ± 0.32 |

All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations each with three measurements

TCE-thuja cone extract; PSE-peach seed extract; TAE-tannic acid equivalent; CE-catechin equivalent; gdw-gram dry weight

According to Yigit et al. (2009) the contents of phenolic compounds of both methanol and water extracts of the Prunus species fruit (apricot) bitter kernel were lower than sweet kernel extracts, each containing 100 μg/mL solid. The highest phenolic content (7.9 ± 0.2 μg/mL) was detected in the water extract of a sweet apricot kernel, while the lowest phenolic content was 0.4 ± 0.1 μg/mL in the water extract of the bitter apricot kernel. Thus, some of the water soluble phenolic compounds such as, anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins present abundantly in extracts of TCE and PSE.

Reducing power and total flavonoid contents

The reducing power of TCE was higher but very low in PSE i.e. 3.32 ± 0.01 and 0.49 ± 0.01 respectively. High reducing activity at low concentration indicates high antioxidant potential. Previous studies have reported that the reducing power of bioactive compounds was associated with the antioxidant activity (Siddhuraju and Klaus 2003; Yen et al. 1993). In present study total flavonoid contents were 7.48 ± 0.02 and 0.85 ± 0.01 mg CE/gdw respectively for TCE and PSE. Flavonoids constitute the largest group of plant phenolics, accounting for over half of the eight thousand naturally occurring phenolic compounds (Harborne et al. 1999).

DPPH radical scavenging activities

The DPPH radical SA of TCE and PSE is shown in Table 1 both extract showed a stronger DPPH radical scavenging activity (25.52 ± 1.92 and 24.99 ± 0.32 respectively). Free radical scavenging ability by hydrogen donation is a known mechanism for antioxidation. The data obtained in this study revealed that the extracts obtained from thuja cones and peach seeds were free radical scavengers which reacted with DPPH radical by their hydrogen donating ability (Fig. 1). In a previous study Prasad et al. (2009) reported SA of 42% for BHT at 100 μg/ml extract concentration. In another experiment the DPPH SA of the extract of thuja twigs was found to be 73.35 ± 1.04% at 300 μg/ml (Dubey and Batra 2009). The DPPH radical scavenging activities of water and methanol extracts from other Prunus species fruit (apricot) cultivars were also reported by Yigit et al. (2009). According to this research a concentration of 100 μg/mL, the water and methanol extracts of the sweet kernel exhibited 89.9 and 87.7% scavenging activity, respectively. In present work, the obtained DPPH radical scavenging activity of both extract indicated it could be a good candidate in the search of natural, effective substances with antioxidant activity.

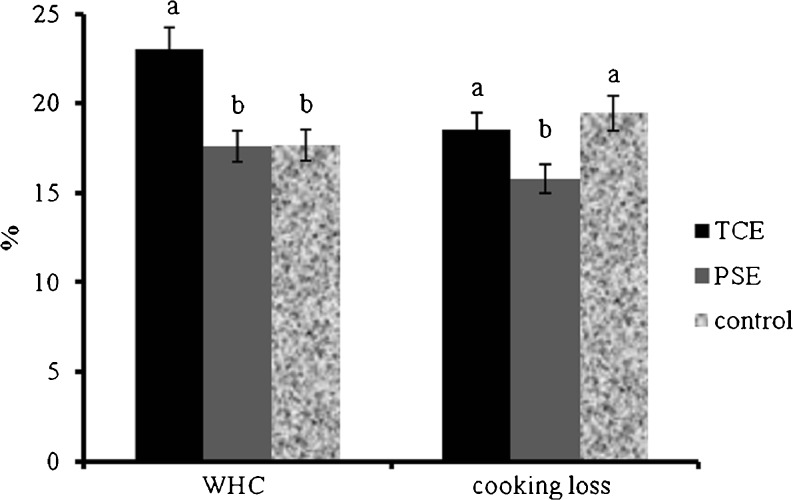

WHC and Cooking loss of ground meat treated with TCE and PSE

The properties of treated GM and control group are shown in Fig. 2. WHC and Cooking losses were differed significantly (P < 0.01) between treated and control group. WHC of TCE and PSE treated ground meat was 23.06 ± 0.23 and 17.59 ± 0.37% respectively which was significantly better than control (17.68 ± 0.49) group, likewise cooking loss were significantly higher in control group (19.47 ± 0.39%) than TCE and PSE treated ground meat (18.56 ± 0.67% and 15.80 ± 0.53% respectively) which might be due to some emulsifying capacity of TCE and PSE that increased the binding properties of meat proteins and fibres in complex matrix.

Fig. 2.

Cooking loss and water holding capacity (WHC) of treated and control raw chicken minced meat. (mean ± S.D; Different letters on the top of columns indicate significant difference at p < 0.05 (n = 9). (GM-ground meat; TCE-thuja cone extract; PSE-peach seed extract

Color stability of ground meat treated with TCE and PSE

Different color properties results obtained in present study are shown in Table 2. The L values [lightness (100) to darkness (0)] were nonsignificant at d0 and d2 of storage period while significant and more in PSE (52.25 ± 1.06) and TCE (51.32 ± 2.03) treated group than control (49.09 ± 3.82) at d4. At d8 the L values again differed significantly (P < 0.01) and found more in PSE treated group. The rate of L value decrease (increase darkness) was observed more in TCE treated and control group than PSE treated group.

Table 2.

Color L, a and b values of ground chicken meat with various treatments during refrigerated (4 ± 1 °C) storage

| Treatment | d0 | d2 | d4 | d6 | d8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | GM + TCE | 59.0 ± 2.48 | 55.4 ± 2.16 | 51.3 ± 2.03ab | 48.1 ± 1.84b | 46.3 ± 1.80c |

| GM + PSE | 56.3 ± 2.21 | 54.4 ± 1.75 | 52.3 ± 1.06a | 54.2 ± 1.99a | 54.5 ± 1.20a | |

| control | 58.8 ± 2.79 | 56.2 ± 1.98 | 49.1 ± 3.82b | 49.0 ± 1.61b | 48.2 ± 2.11b | |

| Treatment effect | NS | NS | * | ** | ** | |

| a | GM + TCE | 8.1 ± 0.21a | 10.6 ± 1.33 | 9.4 ± 1.76b | 10.5 ± 1.20a | 11.3 ± 0.81a |

| GM + PSE | 6.5 ± 0.16b | 10.0 ± 1.22 | 7.8 ± 0.58b | 8.9 ± 1.08b | 9.2 ± 0.62b | |

| control | 6.3 ± 0.69b | 10.6 ± 0.93 | 11.5 ± 2.44a | 10.6 ± 0.24a | 9.4 ± 0.24b | |

| Treatment effect | ** | NS | ** | ** | ** | |

| b | GM + TCE | 17.5 ± 0.66a | 21.9 ± 0.99a | 20.4 ± 0.90a | 20.0 ± 0.60a | 18.5 ± 0.24a |

| GM + PSE | 14.9 ± 0.76b | 19.6 ± 1.12b | 17.6 ± 0.21b | 17.6 ± 1.00c | 17.1 ± 0.41b | |

| control | 15.1 ± 1.86b | 22.2 ± 1.21a | 20.1 ± 0.70a | 18.8 ± 0.32b | 16.5 ± 0.16c | |

| Treatment effect | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | |

(GM-ground meat; TCE-thuja cone extract; PSE-peach seed extract

All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of eight determinations

Values bearing different superscript in a column differ significantly (P < 0.05); NS-nonsignificant

**P < 0.01; *P < 0.05

Redness [a value (positive-red; negative-green)] increased gradually from d0 to d2 in all groups. At d2 a values were nonsignificant between groups. After 2 days in TCE and PSE treated group values were decreased but again increased during d4 to d8. In control group the a values were increased during d0 to d4 period and afterward decreased values were obtained.

Likewise yellowness [b values (positive-yellow; negative-blue)] increased initially in all groups from d0 to d2. The values were differed significantly (P < 0.01) and more in control group than treated groups at d2. The b values at d8 differed significantly (P < 0.05) and more in TCE and PSE treated group than control group.

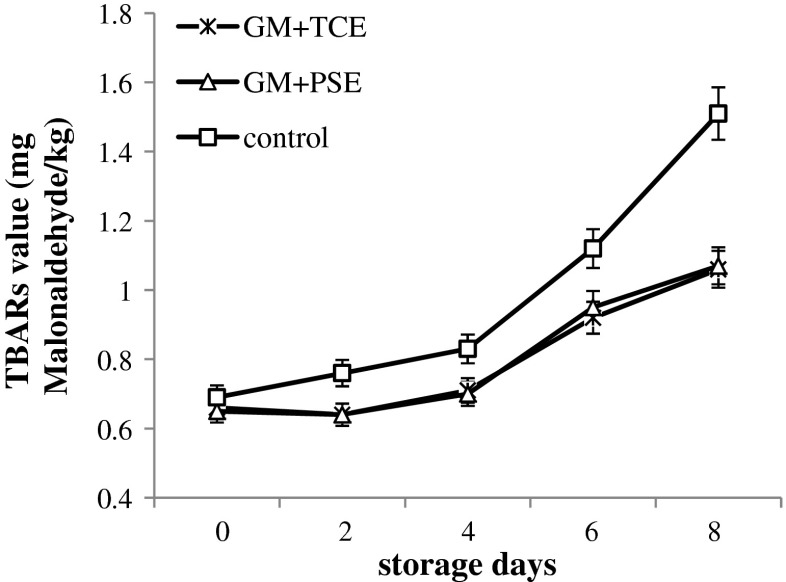

Oxidative stability of ground meat treated with TCE and PSE

The TBARs values correlates with oxidative stability of meat products and usually presented as mg malonaldehyde per Kg of product. The Thiobarbituric acid value determines the extent of lipid oxidation.

The antioxidant effect of the treatments, measured as the change in lipid oxidation value during 8 days of storage, is shown in Fig. 3. The initial concentrations of TBARS in the control and all treated meat samples were between 0.65 ± 0.03 and 0.69 ± 0.02 mg malonaldehyde per Kg and not significantly different. Treated groups showed significant (P < 0.01) less amount of TBARs as compared to control group during whole storage period. The values were non significant between TCE and PSE treated sample. Results obtained from present study indicating that these extracts effectively protected against lipid oxidation of raw chicken meat.

Fig. 3.

TBARs (mg Malonaldehyde/kg) values of treated and control raw chicken minced meat during refrigerated (4 ± 1 °C) storage (n = 9). (GM-ground meat; TCE-thuja cone extract; PSE-peach seed extract; TBARs-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances)

The phenolic compounds of these extracts might be involved in the inhibition of lipid oxidation, because phenolic compounds can inhibit free radical formation and the propagation of free radical reactions through the chelation of transition metal ions, particularly those of iron and copper (Brown et al. 1998). Lee and Ahn (2003) found that phenolic compounds such as gallate and sesamol were effective antioxidants in reducing TBARS in turkey breast during 5 days of storage. Chen et al. (1999) reported that phenolic compounds such as quercetin were also effective in preventing lipid oxidation in both raw and cooked turkey during 7 days of storage. According to study conducted by Yigit et al. (2009) in another prunus variety (apricot) the highest percent inhibition of lipid peroxidation was found 68.6%/100 μg solid in methanol extracts of the sweet kernel. This was followed by the water extract from the same cultivar, which demonstrated 66.3% inhibition. Likewise, in previous studies rosemary extract (Karpińska-Tymoszczyk 2011), ground mustard (Kumar and Tanwar 2011) and BHA (Sureshkumar et al. 2010) was found to be the effectual antioxidant in turkey meat balls, chicken nuggets and buffalo meat sausage respectively during various storage conditions.

Conclusion

Thuja (Thuja occidentalis) cones extract (TCE) and peach (Prunus persia) seeds extract (PSE) contain high levels of bioactive phenolics, flavonoids and other free radical scavengers that can help to control lipid oxidation. This study showed that TCE and PSE had effective antioxidant activity in raw ground chicken meat during refrigerated storage because use of these extracts inhibited the formation of lipid peroxide and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in ground chicken meat. These extract also positively affect water holding capacity and cooking loss. However, Prunus family kernels and thuja cones also possess some antinutritional and other compounds which produced toxicity when consumed more in certain studies, so it should be looked out and further studies especially in regard to isolation and characterization of particular compounds from these extract; which increased the oxidative stability and functional properties of ground meat are needed in order to reinforce these conclusions.

References

- Altmann HJ, Grunow W, Mohr U, Richter-Reichhelm HB, Wester PW. Effects of BHA and related phenols on the forestomach of rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 1986;24:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(86)90306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JE, Khodr H, Hider RC, Rice-Evans CA. Structural dependence of flavonoid interactions with Cu2+ ions: implications for their antioxidant properties. Biochem J. 1998;330:1173–1178. doi: 10.1042/bj3301173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camo J, Beltrán JA, Roncalés P. Extension of the display life of lamb with an antioxidant active packaging. Meat Sci. 2008;80:1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Jo C, Lee JI, Ahn DU. Lipid oxidation, volatiles and color changes of irradiated turkey patties as affected by antioxidants. J Food Sci. 1999;64:16–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1999.tb09852.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey SK, Batra A. Role of phenolics in anti-atherosclerotic property of thuja occidentalis linn. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2009;13:791–800. [Google Scholar]

- Escarpa M, Gonzalez C. Approach to the content of total extractable phenolic compounds from different food samples by comparison of chromatographic and spectro photometric method. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;427:119–127. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)01188-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fasseas MK, Mountzouris KC, Tarantilis PA, Polissiou M, Zervas G. Antioxidant activity in meat treated with oregano and sage essential oils. Food Chem. 2007;106:1188–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.07.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Antioxidants in human health and disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 1996;16:33–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne JB, Baxter H, Moss GP. Phytochemical dictionary: handbook of bioactive compounds from plants. 2. London: Taylor & Francis; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Edamatsu R, Hiramatsu M, Mori A, Fujita Y, Yasuhara T, Yoshida Y, Okuda T. Effects of interactions of tannins with co-existing substances. VI. Effects of tannins and related polyphenols on superoxide anion radical and on DPPH radical. Chem Pharm Bull. 1989;37:2016–2021. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasha GK, Singh RP, Sakariah KK. Antioxidant activity of grape seed (Vitis vinifera) extracts on peroxidation models in vitro. Food Chem. 2001;73:285–290. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00298-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HK, Kang GH, Na JC, Yu DJ, Kim DW, Lee SJ, Kim SH. Effects of feeding Rhus verniciflua extracts on egg quality and performance of laying hens. Korean J Food Sci Anim resour. 2008;28(5):610–615. [Google Scholar]

- Karpińska-Tymoszczyk M (2011) The effect of oil-soluble rosemary extract, sodium erythorbate, their mixture, and packaging method on the quality of Turkey meatballs. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0359-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumar D, Tanwar VK. Effects of incorporation of ground mustard on quality attributes of chicken nuggets. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;48:759–762. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0149-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Ahn DU. Effect of antioxidants on the production of offodor volatiles and lipid oxidation in irradiated turkey breast meat and meat homogenates. J Food Sci. 2003;68:1631–1638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb12304.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RH. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combination of phytochemicals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:517S–520S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.517S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser B, Bodinet C, Tegtmeier M, Lindequist U. Thuja occidentalis (Arbor vitae): a review of its pharmaceutical, pharmacological and clinical properties. Evidence Based Compl Altern Med. 2005;2(1):69–78. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveena BM, Sen AR, Vaithiyanathan S, Babji Y, Kondaiah N. Comparative efficacy of pomegranate juice, pomegranate rind powder extract and BHT as antioxidants in cooked chicken patties. Meat Sci. 2008;80(4):1304–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CI, Kim YJ. Effects of dietary mugwort powder on the VBN, TBARS, and fatty acid composition of chicken meat during refrigerated storage. Korean J Food Sci Anim resour. 2008;28(4):505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad NK, Yang B, Zhao M, Wang B, Chen F, Jiang Y. Effects of high pressure treatment on the extraction yield, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) fruit pericarp. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2009;44:960–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01768.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Bolwell PG, Bramley PM, Pridham JB. The relative antioxidant activity of plant derived polyphenolic flavonoids. Free Radic Res. 1995;22:375–383. doi: 10.3109/10715769509145649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz D, Egea J, Tomas-Barberan FA, Gil MI. Carotenoids from new apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) varieties and their relationship with flesh and skin color. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;53:6368–6374. doi: 10.1021/jf0480703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddhuraju P, Klaus B. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from thre different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/jf020444+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Murthy KN, Jayaprakasha GK. Chidambaram antioxidant activity of pomegranate (Punica garanatum) peel and seed extracts using in vitro models. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:81–86. doi: 10.1021/jf010865b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Yin JJ, Charles D, Zhou K, Moore J, Yu L. Total phenolic contents, chelating capacities, and radical-scavenging properties of black peppercorn, nutmeg, rosehip, cinnamon and oregano leaf. Food Chem. 2007;100:990–997. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.10.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sureshkumar S, Kalaikannan A, Dushyanthan K, Venkataramanujam V. Effect of nisin and butylated hydroxy anisole on storage stability of buffalo meat sausage. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:358–363. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw FR, McCaskill LH, Acton JC. Effect of post mortem changes on poultry meat loaf properties. J Food Sci. 1973;38:421–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1973.tb01444.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witte VC, Krause GF, Bailey MF. A new extraction method for determining 2-thiobarbituric acid values of pork and beef during storage. J Food Sci. 1970;35:582–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1970.tb04815.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojdylo A, Oszmiański J, Czemerys R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007;105:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yen GC, Duh PD, Tsai C. Relationships between antioxidant activity and maturity of peanut hulls. J Agric Food Chem. 1993;41:67–70. doi: 10.1021/jf00025a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit D, Yigit N, Mavi A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of bitter and sweet apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) kernels. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42:346–352. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2009000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogesh K, Ahmad T, Manpreet G, Mangesh K, Das P (2012) Characteristics of chicken nuggets as affected by added fat and variable salt contents. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-012-0617-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhishen J, Mengcheng T, Jianming W. Research on antioxidant activity of flavonoids from natural materials. Food Chem. 1999;64:555–559. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]