ABSTRACT

Mycotoxins are fungal secondary metabolites that contaminate various feedstuffs and agricultural crops. The contamination of food by mycotoxins can occur before production, during storage, processing, transportation or marketing of the food products. High temperature, moisture content and water activity are among the predisposing factors that facilitate the production of mycotoxins in food. Aflatoxins, ochratoxins, fumonisins, deoxynivalenol and zearalenone are all considered the major mycotoxins produced in food and feedstuffs. In Africa, mycotoxin contamination is considered to be a major problem with implications that affect human and animal health and economy. Aflatoxin-related hepatic diseases are reported in many African countries. Ochratoxin and fumonisin toxicity in humans and animals is widespread in Africa. The available, updated information on the incidence of mycotoxin contamination, decontamination and its public health importance in Africa is lacking. The aim of this review is to highlight, update and discuss the available information on the incidence of mycotoxins in African countries. The public health implications and the recommended strategies for control of mycotoxins in food and agricultural crops are also discussed.

Keywords: Africa, health hazards, mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are fungal secondary metabolites produced by the toxigenic strains of the fungi, and these compounds contaminate various food substances and agricultural crops [23]. Aspergillus, Penicillium and Fusarium are known to be the major mycotoxin-producing fungi. The most important mycotoxins produced include aflatoxin (AF), ochratoxins (OT), deoxynivalenol (DON), zearalenone (ZEA), fumonisin (FUM) and trichothecenes (T). Furthermore, DON, ZEA, FUM and T are all produced by the Fusarium species [76].

The predisposing conditions for mycotoxin production relate mainly to poor hygienic practices during transportation and storage, high temperature and moisture content and heavy rains [23]. These conditions are typically observed in different African countries. The demand for the storage of food substances has been increased due to the increasing in the population in African continent. However, improper storage, transportation and processing facilities may facilitate fungal growth and subsequently lead to mycotoxin production and contamination of food and feedstuffs [10].

The food-borne mycotoxins are of great importance in Africa and other parts of the world. The impact of such toxins on human health, animal production and economy has attracted worldwide attention [77].

There is a strong association between cancer risk in human population and exposure to foods naturally contaminated with AFs [54]. FUMs have been enclosed in some animal diseases, such as leukoencephalomalacia in equines, porcine pulmonary edema, rat liver cancer and hemorrhage in the brain of rabbits [51].

Many African countries had started to set up prevention, control and surveillance strategies to reduce the incidence of mycotoxins in foods. The available information on the incidence, public health importance, prevention and control of mycotoxins in many African countries is still lacking. This may be due to limited monitoring systems and failure to adopt preventive and control measures in these countries.

In this review, we will update and discuss the available information on the occurrence, public health importance, prevention and control of mycotoxins in Africa.

Two main mycotoxins, AFs and FUMs, have been reported to be widespread in major dietary food products in African countries. AFs occur mostly in maize, spices and groundnuts, but the prevalence of FUMs is mostly reported on maize from different parts of Africa [8]. Limited surveys have also established a presence of OT, T and ZEA in Africa [57].

NORTH AFRICAN COUNTRIES

In Egypt, mycotoxins are a concern for public health. The major sources of mycotoxins in Egypt are spices, agricultural crops, meat and milk products. A survey was performed to detect AFs in fresh and processed meat products in Cairo. Beef burgers, sausage and luncheon meat had the highest mould count in comparison to fresh and canned meat. In a total of 150 samples of meat products and 100 samples of spices, aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) was detected in 5 samples of beef burger (8 µg/kg), 4 samples of black pepper (35 µg/kg) and 4 samples of white pepper (22 µg/kg). Also, AFs B1 and G1 were detected in two samples of turmeric (12 µg B1/kg and 8 µg G1/kg) and coriander (8 µg B1/kg and 2 µg G1/kg) (Table 1). There was a positive correlation between the addition of spices to fresh meats and AF contamination [4]. In another study, samples of common Egyptian foods (17 nuts and seeds, 10 spices, 31 herbs and medicinal plants, 12 dried vegetables and 28 cereal grains) were collected from markets in Cairo and Giza. The highest content of AFB1 was in nuts and seeds (82%), followed by spices (40%), herbs and medicinal plants (29%), dried vegetables (25%) and cereal grains (21%). The highest mean concentration of AFB1 was in herb and medicinal plants (49 µg/kg) followed by cereals (36 µg/kg), spices (25 µg/kg), nuts and seeds (24 µg/kg) and dried vegetables (20 µg/kg). The highest concentrations of AFB1 were detected in foods that required drying during processing and storage, such as pomegranate peel, watermelon seeds and molokhia (Table 1) [67].

Table 1. Incidence of mycotoxins in the agricultural crops and food stuffs in different African countries.

| Country | Mycotoxin | Food stuffs | Concentration (ppb) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | AFs | Meat products | 2–150 | Aziz and Youssef, 1991 |

| Spices | 2–35 | Selim et al., 1996 | ||

| Cereal grains | 36 | Motawee et al., 2009 | ||

| Nuts and seeds | 24 | El-Tras et al., 2011 | ||

| Medicinal plants | 49 | |||

| Milk | 50–270 | |||

| Infant milk formula | 9.796 | |||

| Tunisia and Morocco | NIV | Cereals and cereal products | 135–961 | Serrano et al., 2012 |

| Beauvericin | ,, | 2.1–844 | ||

| AFs | ,, | 5.5–66.7 | ||

| OTA | ,, | 75–112 | ||

| FUMs | ,, | 121–176 | ||

| Sudan | AFs | Sesame oil | 0.2–0.8 | Idris et al., 2010 |

| Groundnut oil | 0.6 | El shafie et al., 2011 | ||

| Peanuts butter | 21–170 | |||

| Tanzania | FUMs | Maize | 11,048 | Kimanya et al., 2008 |

| AFs | ,, | 158 | ||

| Zambia | FUMs | Maize | 20,000 | Mukanya et al., 2010 |

| Uganda | AFs | Groundnuts, cassava, millet, sorghum flour and eshabwe sauce | 0–55 | Kitya et al., 2010 |

| Kenya | AFs | Animal feed and milk | >5 | Kang’ethe and Lang’a, 2009 |

| Maize | >20 | Daniel et al., 2011 | ||

| Ethiopia | AFs | Shiro and ground red pepper | 100–525 | Fufa and Urga, 1996 |

| AFs | Sorghum, barley, teff and wheat | 0–26 | Ayalew et al., 2006 | |

| OTA | Sorghum, barley and wheat | 54.1–2,106 | ||

| DON | Sorghum | 40–2,340 | ||

| FUM | ,, | 2,117 | ||

| ZEA | ,, | 32 | ||

| Nigeria | AFs | Rice | 28–372 | Makun et al., 2011 |

| OTA | ,, | 134–341 | Oluwafemi and Ibeh, 2011 | |

| AFs | Weaning food | 4.6–530 | ||

| Ghana | AFs | Maize | 0.7–355 | Kpodo, 1996 |

| FUMs | ,, | 70–4,222 | Kpodo et al., 2000 | |

| Benin | AFs | Maize | 5 | Hell et al., 2000 |

| Chips | 2.2–220 | Bassa et al., 2001 | ||

| Benin, Mali and Togo | AFs | Dried vegetables (Baobab leaves, hot chili and okra, etc.) | 3.2–6.0 | Hell et al., 2009 |

| Burkina Faso | AFs | Groundnuts | 170 | Yameogo and Kassamba, 1999 |

| South Africa | FUMs | Maize | 222–1,142 | Burger et al., 2010 |

| FUMs | Compound feeds | 104–2,999 | Njobeh et al., 2012 | |

| DON | ,, | 124–2,352 | ||

| ZEA | ,, | 30–610 | ||

| Lesotho | ZEA | Sorghum beer | 50 | Gilbert 1989 |

Screening of the mycological image of luncheon meats produced by 2 big companies in Egypt was conducted. The luncheon meat samples analyzed were relatively highly contaminated by moulds and yeasts. The most frequently encountered fungi from the samples were yeasts, Aspergillus niger, A. flavus, Penicillium chrysogenum, Rhizopus stolonifer and Mucor circinelloides. The most important aflatoxigenic species, A. flavus, was isolated frequently. It represented 10% of the total fungal isolates from both samples of the two companies [39]. In addition, a survey of aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) in cow, goat, buffalo and camel milks in Ismailia, Egypt, was also performed. All milk samples in this study had AFM1 levels less than the United States maximum allowable level (i.e.,<500 ng/l [22]). Some milk samples were above the European limit (i.e.,>50 ng/l) [13], although most were less than 150 ng/l. Milk from camels had the lowest AFM1 levels with 80% being less than 50 ng/l compared to 74%, 66% and 52% for goat, cow and buffalo milks, respectively, that may be due to the free-range pasture feeding in camel without any prepared rations. The highest concentrations of AFM1 were 210, 220 and 230 ng/l found in camel, cow and goat milks, respectively, and 92% of the camel milk samples had AFM1 levels less than 150 ng/l [55] (Table 1).

The contents of 14 mycotoxins were studied in samples of different cereals (rice, wheat, maize, rye, barley, oat, spelt and sorghum) and cereal products (snacks, pasta, soup, biscuits and flour) from 2 countries of the Mediterranean region. Two hundred and 65 samples from Morocco and Tunisia were analyzed. The percentage of total samples contaminated was 53%. The frequency of contaminated samples from Tunisia and Morocco was 96% and 50%, respectively. Nivalenol (NIV) and beauvericin were the most predominant mycotoxins. The concentration ranges of NIV and beauvericin in the contaminated samples were 135–961 µg/kg and 2.1–844 µg/kg, respectively [68] (Table 1).

The highest incidence of AF contamination occurred in sesame (43.75%), followed by groundnut (3.57%) in several localities in the Kordofan, Gezira and Khartoum states, Sudan. AFB1 levels in sesame oil samples ranged from 0.2–0.8 µg/kg and were in an average of 0.6 µg/kg in groundnut oil samples [35] (Table 1). In addition, AFB1 was detected at variable levels in 100% of the screened samples of peanut butter purchased from local markets in Khartoum [19].

CENTRAL AFRICAN COUNTRIES

In Tanzania, FUMs were determined at levels up to 11,048 µg/kg and in 15% levels exceeded 1,000 µg/kg in maize samples at 2005. AFs were detected in 18% of the samples at levels up to 158 µg/kg. Twelve percent of the samples exceeded the Tanzanian limit for total AFs (10 µg/kg). AFs co-occurred with FUMs in 10% of the samples [45].

In Zambia, the concentrations of FUMs in maize from 6 districts and AFs from 2 districts in Lusaka were 10-fold higher than 2 mg/kg and far higher than the 2 µg/kg maximum daily intake recommended by the FAO/WHO [56].

EAST AFRICAN COUNTRIES

In Uganda, AF levels in the food samples (groundnuts, cassava, millet, sorghum flour and eshabwe sauce) ranged from 0 to 55 µg/kg with a mean value of 15.7 ± 4.9 µg/kg. Eshabwe sauce had the highest mean total AF levels (18.6 ± 2.4 µg/kg) [46].

In Kenya, a total of 830 animal feed and 613 milk samples from 4 urban centers were analyzed for AFB1 and M1. Eighty-six percent of the feed samples were positive for AFB1, and sixty-seven percent of these exceeded the FAO/WHO level of 5 µg/kg. Seventy-two percent of the milk samples was positive for AFM1 [43]. In addition, AF poisonings associated with eating contaminated maize had been documented in eastern Kenya with a case-fatality rate of 40%. During the years of outbreaks in 2005 and 2006, 41% and 51% of maize samples, respectively, had AF levels above the Kenyan regulatory limit of 20 µg/kg in grains for human consumption [14] (Table 1). In addition, OTA contamination of coffee batches was also reported [17].

In Ethiopia, AF contamination of Shiro and ground red pepper samples collected from open markets in Addis Ababa was investigated. From 60 samples, each of ground red pepper and Shiro, 8 (13.33%) and 5 (8.33%) were positive for AFs, respectively. AF levels in Shiro and ground red pepper positive samples ranged from 100–500 µg/kg and 250–525 µg/kg, respectively [24] (Table 1). In another study, the occurrence of mycotoxins in barley, sorghum, teff and wheat was examined. AFB1 and OTA were detected in samples of all four crops. AFB1 was detected in 8.8% of the samples analyzed at concentrations ranging from trace amounts to 26 µg/kg. OTA occurred in 24.3% of the samples at a mean concentration of 54.1 µg/kg and a maximum of 2,106 µg/kg (Table 1). DON occurred in barley, sorghum and wheat at 40–2,340 µg/kg with an overall incidence of 48.8% among the samples analyzed. FUM and ZEA occurred only in sorghum samples with low frequencies at concentrations reaching 2,117 and 32 µg/kg, respectively [2].

WEST AFRICAN COUNTRIES

In Nigeria, a report showed that 33% of maize samples from different agro-ecological zones were contaminated with AFs [74]. A survey was conducted on the natural occurrence of AFs and FUMs in preharvest maize from fields in southwestern Nigeria. AFB1 was detected in 18.4% of samples, while AFs B2, G1 and G2 were present in 7.8%, 2.9% and 1% of the samples, respectively, in contaminated samples. FUMB1 was the predominant toxin detected in 78.6% of samples, while FUMB2 was detected in 66% of samples [7]. In another report, AFs were detected in 21 rice samples, at total AF concentrations of 28–372 µg/kg. OTA was found in 66.7% of the samples, also at high concentrations (134–341 µg/kg). ZEA (53.4%), DON (23.8), FB1 (14.3%) and FB2 (4.8%) were also found in rice, although at relatively low levels [50]. In regard to the mycotoxin contamination of the home-made weaning food in Nigeria, it was reported that AFM1 contents ranged from 4.6–530 ng/ml [60].

In Cote d’Ivoire, OTA has been found in millet, maize, rice and peanuts, which constitute the base of diets [65]. In addition, co-occurrence of AFB1, FB1, OTA and ZEA in cereals and peanuts in Cote d’Ivoire was reported [66].

In Ghana, all the maize samples collected from silos and warehouses contained AFs at levels ranging from 20–355 µg/kg, while fermented maize dough collected from major processing sites contained AF levels of 0.7–313 µg/kg [47].

Fifteen maize samples from four markets and processing sites in Accra, Ghana, were analyzed for FUMB1, B2 and B3 (Table 1). All samples contained FUMs with total FUM levels for 14 samples ranging from 70–4,222 µg/ kg [48].

In Benin, it was found that the percentage of maize samples with AF levels exceeding 5 µg/kg was between 9.9% and 32.2% in the different agroecological zones of Benin before storage, but this increased to between 15.0% and 32.2% after 6 months storage [31]. AFs were detected in 98% of samples of dried yam chips surveyed in Benin with levels ranging from 2.2–220 µg/kg and a mean of 14 µg/kg [9] (Table 1).

Fungal infection and AF contamination were evaluated on 180 samples of dried vegetables, such as okra, hot chili, tomato, melon seeds, onion and baobab leaves from Benin, Togo and Mali collected from September to October 2006. Baobab leaves, followed by hot chili and then okra showed a high incidence of fungal contamination compared to the other dried vegetables, while shelled melon seeds, onion leaves and dried tomato had lower levels of fungal contamination. Only okra and hot chili were naturally contaminated with AFB1 and AFB2, at concentrations of 6.0 µg/kg for okra and 3.2 µg/kg for hot chili [32] (Table 1). It was reported that seeds of groundnuts from Burkina Faso inoculated with A. flavus excreted all the four major AFs, which peaked at 170 µg/kg after 6 days [79].

SOUTHERN AFRICAN COUNTRIES

In South Africa, the total mean values of FUM in home-grown and commercial maize was measured at 1,142 µg/kg and 222 µg/kg, respectively. The probable daily intakes of FUM were 12.1 µg/kg and 1.3 µg/kg for men and 6.7 µg/kg and 1.1 µg/kg for women, consuming home-grown and commercial maize, respectively [12]. In another report, a total of 92 commercial compound feeds were investigated for various mycotoxins. The data revealed the highest incidence of feed contamination for FUM (104–2,999 µg/kg) followed by DON (124–2,352 µg/kg) and ZEA (30–610 µg/kg) (Table 1). The incidence of OTA and AF-contaminated samples was generally low [59].

In Swaziland and Lesotho, a report showed that ZEA occurred in mouldy maize on the cob, maize porridge, malted sorghum and sorghum beer. Levels up to 50 µg/kg were detected in sorghum beer from Lesotho [25].

In Zimbabwe, the occurrence of Fusarium species in grains other than maize was reported in a survey on sorghum samples from Zimbabwe and Lesotho. Fusarium species isolated included FUM-producing ones. A survey performed on Zimbabwe cereals, oilseeds and pulses samples yielded Fusarium species except in the case of sunflower. FUMs were detected in all samples including soya beans, which had the lowest levels. Retail cereal products also had detectable FUM levels from a study performed in Zimbabwe [61].

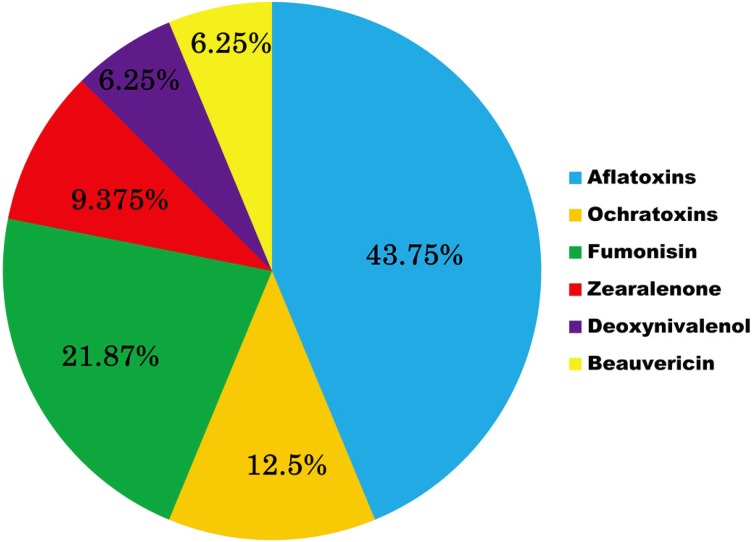

By analysis of the available information in this review, it is clear that AFs showed the highest incidence in the different African countries (43.75%), followed by FUMs (21.87%), OTA (12.5%), ZEA (9.375%), NIV and beauvericin (both at 6.25%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of mycotoxins in African countries.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPORTANCE OF MYCOTOXINS IN AFRICAN COUNTRIES

Consumption of large amounts of toxin in a short period of time will cause acute toxicity leading to death, while small doses over long time will result in chronic effects to the consumer. AFs bind to DNA and disrupt genetic coding, thus promoting carcinogenesis. In Africa, among other mycotoxins, AFs have been implicated in human diseases including liver cancer, Reye’s Syndrome, Indian childhood cirrhosis, chronic gastritis, kwashiorkor and certain occupational respiratory diseases. In 1993, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified AFB1 and mixtures of AFs as Group 1 carcinogens [37]. Epidemiological studies of human populations exposed to diets naturally contaminated with AFs revealed positive correlations between the high incidence of liver cancer in Africa and elsewhere and dietary intake consumption of AF [54]. AF consumption raises the risk of liver cancer by more than ten-fold compared to either exposure alone in people with hepatitis B and C viral infection [72].

In Egypt, aflatoxin-albumin (AF–alb) was detected in 24/24 samples from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)-negative individuals and 7/22 samples from HCC-positive cases (Table 2). A cross-sectional study assessed serum AF-alb, urinary AFM1 and urinary DON in 98 pregnant women from Egypt, in relation to diet and socioeconomic status, during the third trimester. AF-alb was detected in 34/98 (35%) samples, AFM1 in 44/93 (48%) samples, while DON was detected in 63/93 (68%) samples. AFs and DON biomarkers were observed in 41% of the subjects concurrently [62]. Additionally, residues of AFM1 were recorded in infant formula milk powder and maternal breast milk, and the concentrations were 74.413 ± 7.070 ng/l and 9.796 ± 1.036 ng/l), respectively [20].

Table 2. Mycotoxin-related public health problems in African countries.

| Country | Mycotoxin | Health Problem | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | AFs | Primary hepatocellular carcinoma | Tumer et al., 2008 |

| Ghana | AFs | Anemia | Shuaib et al., 2010 |

| AFs | Immunodeficiency | Jiang et al., 2005 | |

| Gambia | AFs | Immunodeficiency | Tumer et al., 2003 |

| Liver cirrhosis | Kuniholm et al., 2008 | ||

| Cameroon | AFs | Primary hepatocellular carcinoma | Tchana et al., 2010 |

| Kenya | AFs | Aflatoxicoses | Azziz-Baumgartner et al., 2005 |

| Nigeria | AFs | Infertility | Uriah et al., 2001 |

| Benin | AFs | Stunting and being underweight | Gong et al., 2003 |

| Togo | AFs | Stunting and being underweight | Gong et al., 2003 |

| Tunisia | OTA | Nephropathy | Hmaissia et al., 2012 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | OTA | Nephropathy | Sangare-Tigori et al., 2006 |

There is a striking association between AFs and impaired growth in children [18, 26]. In Ghana, higher levels of AFB1-alb adducts in plasma were associated with lower percentages of certain leukocyte immunophenotypes [42] (Table 2); in addition, a close association between anemia in pregnancy and AFs among pregnant women in Kumasi was reported [69]. Similarly, a study in Gambian children found an association between serum AFs-alb levels and reduced salivatory secretory IgA levels [72] (Table 2). Additionally, AFs and hepatitis B virus exposure appeared to interact synergistically to substantially increase the risk of cirrhosis in Gambia [49] (Table 2). Similarly, both AF and hepatitis B virus seemed to be risk factors that could increase the incidence and prevalence rates of malnutrition and cancer in Cameroon [71] (Table 2). The chronic incidence of AF in diets is evident from the presence of AFM1 in human breast milk in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Sudan and in umbilical cord blood samples in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Sierra Leone [10]. The largest reported outbreak of aflatoxicosis to date occurred in Kenya in 2004 where 317 cases and 215 recognized deaths were reported [5] (Table 2). A study in Nigeria found that blood and semen AF levels ranged from 700–1,393 ng/ml and 60–148 ng/ml, respectively, in infertile men and were significantly higher than that in fertile men [75]. AF-alb adducts were detected in 99% of children in Benin and Togo [26] (Table 2). In birds, diets containing AFB1 and AFB2 could induce pathological lesions in the livers, slightly change the serum biochemical parameters and damage the hepatic antioxidant functions when the inclusion of AFB1- and AFB2-contaminated corn reached or exceeded 50% [80].

OTs, particularly OTA, are known to be nephrotoxic. OTA has been suggested to be a factor in the etiology of endemic nephropathy. OTA is nephrotoxic, teratogenic, carcinogenic and immunosuppressive in many animal species. The IARC has classified OTA as possibly carcinogenic in humans (group 2B carcinogen) [36]. A strong correlation between serum OTA and nephropathy was reported in Tunisia and Cote d’Ivoire [33, 65] (Table 2). The highest levels of OTA residues were also observed in the serum of broilers, followed by the livers and kidneys [28].

FUMs have been implicated in a number of animal diseases in equines, pigs, rats and rabbits. These diseases are characterized by hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in these animals [34]. The prevalence of FUMs has been reported to be 100% or close to it in all surveillance data that have been reported on maize from different parts of Africa [8]. ZEA mimics estrogens in swine, resulting in feed refusal and emesis [70]. Deoxynivalenol has an immunosuppressant effect in animals, and it is this effect which is of significance in view of the likely chronic exposure to low levels of this mycotoxin [70].

Citrinin (CTN) and patulin (PAT) caused profound nephrotoxicity as observed from histology and analysis of biological function in zebrafish embryos. Inflammation and blood rheology may be involved in CTN-induced renal impairment [78].

CONTROL OF MYCOTOXIN PROBLEMS IN AFRICA

Control of mycotoxin in Africa is a matter of importance not only for health implications, but also for improvement of economy in the affected countries. Thus, a number of strategies for reduction and control of mycotoxins have been considered in different African countries. The control of mycotoxins in Africa involves: a) prevention of mould growth in crops and other feedstuffs; b) decontamination of mycotoxin-contaminated foods as a secondary strategy; and c) continuous surveillance of mycotoxins in agricultural crops, animal feedstuffs and human food.

Prevention of mould growth in crops and other feedstuffs: This aim could be achieved by following strict hygienic precautions during harvesting, storage and processing of agricultural crops and feedstuffs.

Hygienic agricultural practices include early harvesting of the crops. Early harvesting of groundnuts resulted in lower AF levels and higher gross returns of 27% as compared to delayed harvesting [64]. Proper drying and storage of the crops are considered effective tools for reduction of mould growth and mycotoxin production. A trial in Guinea focused on thorough drying and proper storage of groundnuts, and this achieved a 60% reduction in mean AF levels [73].

Decontamination of mycotoxin-contaminated foods: Physical approaches, such as sorting, washing and crushing combined with de-hulling of maize grains, were effective in achieving significant AF and FUM removal in Benin [21].

Chemical approaches are considered as the most effective method for mycotoxin decontamination despite some of the implications on food safety. FUMs contamination could be reduced by application of fungicides that have been used in control of Fusarium head blight, such as prochloraz, propiconazole, epoxyconazole, tebuconazole cyproconazole and azoxystrobin [27]. On the other hand, application of fungicides has been shown to effectively control the AF-producing Aspergillus species [58]. Chemical reduction of FUM toxicity can be achieved through the use of allyl, benzyl and phenyl isothiocyanate in model solution and in food products [3]. The BEA reduction varied from 10% to 65% in wheat flour and was dose-dependent with allyl isothiocyanate [53].

Chemoprotection of AFs has been used with the use of a number of chemical compounds, such as oltipraz and chlorophylin [30]. Dietary substances, such as broccoli sprouts and green tea that either increases animal’s detoxification processes [44] or prevents the production of the epoxide that leads to chromosomal damage [30], are considered as effective tools for reducing the health hazards caused by various mycotoxins. AF-induced changes in the liver of mice were significantly reduced with co-treatment of black tea extract [41].

Using of calcium hydroxide and hydrogen peroxide during the washing step of white pepper effectively reduced AFB2 and AFG2 by 68.5% and 100%, respectively [40]. Additionally, ozone has the ability to control aflatoxigenic fungal growth, and thus, it is considered as is an important alternative for peanut detoxification [15]. Gamma radiation is also effective in reduction of total mould counts in a dose-dependent fashion [38].

Biological approaches are based on developing atoxigenic fungi that compete with toxigenic ones in the field environment. Introduction of atoxigenic strains of A. flavus and A. parasiticus to soil of developing crops has resulted in 74.3% to 99.9% reduction in AF contamination in peanuts in the USA [16]. The use of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae reduced the AFB1 concentration in peanuts by 74.4% [1, 63]. Control of FUM-producing fungi by endophytic bacteria has also been reported [6]. In vitro inhibition of OTA production by A. ochraceus by three yeasts (Pichia anomala, P. kluyveri and Hanseniaspora uvarum) was also reported [52]. The usage of Trichosporon mycotoxinivorans as an OTA deactivator in broiler feeds has been recently reported [28]. Lactic acid bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, could be a promising biological control strategy for PAT in aqueous solutions [29].

Fungal strains of Trichoderma have also been demonstrated to control pathogenic fungi through mechanisms, such as competition for nutrients and space, fungistasis, antibiosis, rhizosphere modification, mycoparasitism, biofertilization and the stimulation of plant-defense mechanisms [11].

Continuous surveillance of mycotoxins in agricultural crops, animal feedstuffs and human food: In addition, education of African populations about mycotoxins, their health hazards and ways to protect against such toxins remains a matter of significance. Additionally, holding seminars, workshops and media announcements addressing this problem are very important strategies for controlling mycotoxins in African countries. However, these continuous efforts are impeded by limitations in these areas, the foremost of which being the shortage of research funding and technology in many institutes and universities that facilitate this surveillance in various African countries. The second problem is the lacking experience of individuals working on this issue. Thus, in order to overcome mycotoxin contamination in African countries, all international efforts must gather to help address this issue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, which was awarded to M. Ishizuka (No. 24405004) and from the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) to W.S. Darwish (No.23001097). W. S. Darwish is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Japanese Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS). Core to Core program by JSPS also supported this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armando M. R., Dogi C. A, Rosa C. A, Dalcero A. M., Cavaglieri L. R.2012. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains and the reduction of Aspergillus parasiticus growth and aflatoxin B1 production at different interacting environmental conditions, in vitro. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 29: 1443–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayalew A., Fehrmann H., Lepschy J., Beck R., Abate D.2006. Natural occurrence of mycotoxins in staple cereals from Ethiopia. Mycopathologia 162: 57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11046-006-0027-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azaiez I., Meca G., Manyes L., Luciano F. B., Fernández-Franzón M.2012. Study of the chemical reduction of the fumonisins toxicity using allyl, benzyl and phenyl isothiocyanate in model solution and in food products. Toxicon pii: S0041-0101(12)00839–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz N. H., Youssef Y. A.1991. Occurrence of aflatoxins and aflatoxin-producing moulds in fresh and processed meat in Egypt. Food Addit. Contam. 8: 321–331. doi: 10.1080/02652039109373981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azziz-Baumgartner E., Lindblade K., Gieseker K., Rogers S., Kieszak S., Njapau H., Schleicher R., McCoy L., Misore A., DeCock K., Rubin C., Slutsker L.2005. Case–Control Study of an Acute Aflatoxicosis Outbreak, Kenya, 2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 113: 1779–1783. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacon C. W., Yates I. E., Hinton D. M., Meredith F.2001. Biological control of Fusarium moniliforme in maize. Environ. Health Perspect. 109: 325–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bankole S. A., Mabekoje O. O.2004. Occurrence of aflatoxins and fumonisins in preharvest maize from south-western Nigeria. Food Addit. Contam. 21: 251–255. doi: 10.1080/02652030310001639558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bankole S., Schollenbeger M., Drochner W.2006. Mycotoxin contamination in food systems in sub-Saharan Africa. 28. Mykotoxin Workshop Hrsg.: Bydgosczz (Polen), 29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassa S., Mestres C., Hell K., Vernia P., Cardwell K.2001. First report of aflatoxin in dried yam chips in Benin. Plant Dis. 85: 1032. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.9.1032A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhat R.V., Vasanthi S.2003. Mycotoxin food safety risks in developing countries. pp. 1–2. Food Safety in Food Security and Food Trade. Vision 2020 for Food, Agriculture and Environment, Focus 10, brief 3 of 17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benítez T., Ana M., Rincón M., Carmen L. A., Codón C.2004. Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma strains. Int. Microbiol. 7: 249–260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burger H. M., Lombard M. J., Shephard G. S., Rheeder J. R., van der Westhuizen L., Gelderblom W. C.2010. Dietary fumonisin exposure in a rural population of South Africa. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48: 2103–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commission Regulation (2006) (EC) No. 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006. Setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Off. J. European Union 364: 5–24 L077:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel J. H., Lewis L. W., Redwood Y. A., Kieszak S., Breiman R. F., Flanders W. D., Bell C., Mwihia J., Ogana G., Likimani S., Straetemans M., McGeehin M. A.2011. Comprehensive assessment of maize aflatoxin levels in Eastern Kenya, 2005–2007. Environ. Health Perspect. 119: 1794–1799. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Alencar E. R., Faroni L. R., Soares N. F., da Silva W. A., Carvalho M. C.2012. Efficacy of ozone as a fungicidal and detoxifying agent of aflatoxins in peanuts. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92: 899–905. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorner J. W., Cole R. J., Blankenship P. D.1998. Effect of inoculum rate of biological control agents on preharvest aflatoxin contamination of peanuts. Biol. Control 12: 171–176. doi: 10.1006/bcon.1998.0634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duris D., Mburu J. K., Durand N., Clarke R., Frank J. M., Guyot B.2010. Ochratoxin A contamination of coffee batches from Kenya in relation to cultivation methods and post-harvest processing treatments. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 27: 836–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egal S., Hounsa A., Gong Y. Y., Turner P. C., Wild C. P., Hall A. J., Hell K., Cardwell K. F.2005. Dietary exposure to aflatoxin from maize and groundnut in young children from Benin and Togo, West Africa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 104: 215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elshafie S. Z., ElMubarak A., El-Nagerabi S. A., Elshafie A. E.2011. Aflatoxin B1 contamination of traditionally processed peanuts butter for human consumption in Sudan. Mycopathologia 171: 435–439. doi: 10.1007/s11046-010-9378-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Tras W. F., El-Kady N. N., Tayel A. A.2011. Infants exposure to aflatoxin M as a novel foodborne zoonosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49: 2816–2819. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fandohan P., Gnonlonfin B., Hell K., Marasas W. F. O., Wingfield M. J.2005. Natural occurrence of Fusarium and subsequent fumonisin contamination in preharvest and stored maize in Benin, West Africa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 99: 173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2005) Sec. 527.400 Whole milk, low fat milk, skim milk aflatoxin M1 (CPG 7106.10). Available from http://www.fda.gov/ora/compliance_ref/cpg/cpgfod/cpg527-400.html

- 23.Food Nutrition and Agriculture (FAO), 1991. Food for the Future. FAO 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fufa H., Urga K.1996. Screening of aflatoxins in Shiro and ground red pepper in Addis Ababa. Ethiop. Med. J. 34: 243–249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert J.1989. Review of Mycotoxins. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Food Science Laboratory. Colney Lane, Norwich. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong Y. Y., Egal S., Hounsa S., Hall A. J., Cardwell K. F., Wild C. P.2003. Determinants of aflatoxin exposure in young children from Benin and Togo, West Africa: the critical role of weaning. Int. J. Epidemiol. 32: 556–562. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haidukowski M., Pascale M., Perrone G., Pancaldi D., Campagna C., Visconti A.2005. Effect of fungicides on the development of Fusarium head blight, yield and deoxynivalenol accumulation in wheat inoculated under field conditions with Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium culmorum. J. Sci. Food Agric. 85: 191–198. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanif N. Q., Muhammad G., Muhammad K., Tahira I., Raja G. K.2012. Reduction of ochratoxin A in broiler serum and tissues by Trichosporon mycotoxinivorans. Res. Vet. Sci. 93: 795–797. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatab S., Yue T., Mohamad O.2012. Reduction of patulin in aqueous solution by lactic acid bacteria. J. Food Sci. 77: 238–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes J. D., Pulford D. J., Ellis E. M., McLeod R., James R. F. L., Seidegard J., Mosialou E., Jernstrom B., Neal G. E.1998. Regulation of rat glutathione- S-transferase A5 by cancer chemopreventive agents: mechanisms of inducible resistance to aflatoxin B1. Chem. Biol. Interact. 111-112: 51–67. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00151-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hell K., Cardwell K. F., Setamou M., Poehling H. M.2000. The influence of storage practices on aflatoxin contamination in maize in four agroecological zones of Benin, West Africa. J. Stored Prod. Res. 36: 365–382. doi: 10.1016/S0022-474X(99)00056-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hell K., Gnonlonfin B. G., Kodjogbe G., Lamboni Y., Abdourhamane I. K.2009. Mycoflora and occurrence of aflatoxin in dried vegetables in Benin, Mali and Togo, West Africa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 135: 99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hmaissia Khlifa K., Ghali R., Mazigh C., Aouni Z., Machgoul S., Hedhili A.2012. Ochratoxin A levels in human serum and foods from nephropathy patients in Tunisia: where are you now? Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 64: 509–512. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard P. C., Eppley R. M., Stack M. E., Warbritton A., Voss K. A., Lorentzen R. J., Kovach R. M., Bucci T. J.2001. Fumonisin B1 carcinogenicity in a two-year feeding study using F344 rats and B6C3F1 mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 109: 277–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Idris Y. M., Mariod A. A., Elnour I. A., Mohamed A. A.2010. Determination of aflatoxin levels in Sudanese edible oils. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48: 2539–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 1993. pp. 489–521. Ochratoxin A. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Some Naturally Occurring Substances: Food Items and Constituents, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Mycotoxins, vol. 56. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2002. pp. 82–171.Traditional Herbal Medicines, Some Mycotoxins, Napthalene, and Styrene. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iqbal Q., Amjad M., Asi M. R., Ariño A.2012. Mold and aflatoxin reduction by gamma radiation of packed hot peppers and their evolution during storage. J. Food Prot. 75: 1528–1531. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ismail M. A., Zaky Z. M.1999. Evaluation of the mycological status of luncheon meat with special reference to aflatoxigenic moulds and aflatoxin residues. Mycopathologia 146: 147–154. doi: 10.1023/A:1007086930216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jalili M., Jinap S.2012. Reduction of mycotoxins in white pepper. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 29: 1947–1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jha A., Shah K., Verma R. J.2012. Aflatoxin-induced biochemical changes in liver of mice and its mitigation by black tea extract. Acta Pol. Pharm. 69: 851–857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang Y., Jolly P. E., Ellis W. O., Wang J. S., Phillips T. D., Williams J. H.2005. Aflatoxin B1 albumin adduct levels and cellular immune status in Ghanaians. Int. Immunol. 17: 807–814. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang’ethe E. K., Lang’a K. A.2009. Aflatoxin B1 and M1 contamination of animal feeds and milk from urban centers in Kenya. Afr. Health Sci. 9: 218–226 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kensler T. W., Egner P. A., Wang J. B., Zhu Y. R., Zhang B. C., Lu P. X., Chen J. G., Qian G. S., Kuang S. Y., Jackson P. E., Gange S. J., Jacobson L. P., Munoz A., Groopman J. D.2004. Chemoprevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in aflatoxin endemic areas. Gastroenterology 127: 310–318. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimanya M. E., De Meulenaer B., Tiisekwa B., Ndomondo-Sigonda M., Devlieghere F., Van Camp J., Kolsteren P.2008. Co-occurrence of fumonisins with aflatoxins in home-stored maize for human consumption in rural villages of Tanzania. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 25: 1353–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitya D., Bbosa G. S., Mulogo E.2010. Aflatoxin levels in common foods of South Western Uganda: a risk factor to hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 19: 516–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kpodo K. A.1996. Mycotoxins in maize and fermented maize products in Southern Ghana. p. 33. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Mycotoxins in Food in Africa. November 6–10, 1995 (Cardwell, K.F. ed.), Cotonou, Benin. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Benin.

- 48.Kpodo K., Thrane U., Hald B.2000. Fusaria and fumonisins in maize from Ghana and their co-occurrence with aflatoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 61: 147–157. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00370-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuniholm M. H., Lesi O. A., Mendy M., Akano A. O., Sam O., Hall A. J., Whittle H., Bah E., Goedert J. J., Hainaut P., Kirk G. D.2008. Aflatoxin exposure and viral hepatitis in the etiology of liver cirrhosis in the Gambia, West Africa. Environ. Health Perspect. 116: 1553–1557. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makun H. A., Dutton M. F., Njobeh P. B., Mwanza M., Kabiru A. Y.2011. Natural multi-occurrence of mycotoxins in rice from Niger State, Nigeria. Mycotoxin. Res. 27: 97–104. doi: 10.1007/s12550-010-0080-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marasas W. F. O.1995. Fumonisins: their implications for human and animal health. Nat. Toxins 3: 193–198. doi: 10.1002/nt.2620030405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masoud W., Kaltoft C. H.2006. The effects of yeasts involved in the fermentation of coffee arabica in East Africa on growth and ochratoxin A (OTA) production by Aspergillus ochraceus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 106: 229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meca G., Luciano F. B., Zhou T., Tsao R., Mañes J.2012. Chemical reduction of the mycotoxin beauvericin using allyl isothiocyanate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50: 1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Medical Research Council (MERCK), 2006. Aflatoxin in peanut butter. Science in Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Motawee M. M., Bauer J., McMahon D. J.2009. Survey of Aflatoxin M1 in Cow, Goat, Buffalo and Camel Milks in Ismailia-Egypt. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 83: 766–769. doi: 10.1007/s00128-009-9840-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukanga M., Derera J., Tongoona P., Laing M. D.2010. A survey of pre-harvest ear rot diseases of maize and associated mycotoxins in south and central Zambia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 141: 213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muthomi J. W., Oerke E. C., Dehne H. W., Mutitu E. W.2002. Susceptibility of Kenyan wheat varieties to head blight, fungal invasion, and deoxynivalenol accumulation inoculated with Fusarium graminearum. J. Phytopathol. 150: 30–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0434.2002.00713.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ni X., Streett D. A.2005. Modulation of water activity on fungicide effect on Aspergillus niger growth in Sabouraud dextrose agar medium. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 41: 428–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Njobeh P. B., Dutton M., Åberg A., Haggblom P.2012. Estimation of multi-mycotoxin contamination in South African compound feeds. Toxins 4: 836–848. doi: 10.3390/toxins4100836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oluwafemi F., Ibeh I. N.2011. Microbial contamination of seven major weaning foods in Nigeria. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 29: 415–419. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i4.8459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Onyike N. B. N., Nelson P. E.1992. Fusarium spp. associated with sorghum grain from Nigeria. Lesotho and Zimhahwe. Mycologia 84: 452–458. doi: 10.2307/3760198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piekkola S., Turner P. C., Abdel-Hamid M., Ezzat S., El-Daly M., El-Kafrawy S., Savchenko E., Poussa T., Woo J. C., Mykkänen H., El-Nezami H.2012. Characterisation of aflatoxin and deoxynivalenol exposure among pregnant Egyptian women. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 29: 962–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prado G., Madeira J. E., Morais V. A., Oliveira M. S., Souza R. A., Peluzio J. M., Godoy I. J., Silva J. F., Pimenta R. S.2011. Reduction of aflatoxin B1 in stored peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Food Prot. 74: 1003–1006. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rachaputi N. R., Wright G. C., Kroschi S.2002. Management practices to minimize pre-harvest aflatoxin contamination in Australian groundnuts. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 42: 595–605. doi: 10.1071/EA01139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sangare-Tigori B., Dem A. A., Kouadio H. J., Betbeder A. M., Baudrimont I., Dano D. S., Moukha S., Creppy E. E.2006a Preliminary survey of ochratoxin A in millet, maize, rice and peanuts in Côte d’Ivoire from 1998 to 2002. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 25: 211–216. doi: 10.1191/0960327106ht605oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sangare-Tigori B., Moukha S., Kouadio H. J., Betbeder A. M., Beaudrimont I., Dano D. S., Creppy E. E.2006b Co-occurrence of aflatoxin B1, fumonisin B1, ochratoxin A and zearalenone in cereals and peanuts in Côte d’Ivoire. Food Addit. Contam. 23: 1000–1007. doi: 10.1080/02652030500415686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Selim M. I., Popendorf W., Ibrahim M. S., el Sharkawy S., el Kashory E. S.1996. Aflatoxin B1 in common Egyptian foods. J. AOAC Int. 79: 1124–1129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Serrano A. B., Font G., Ruiz M. J., Ferrer E.2012. Co-occurrence and risk assessment of mycotoxins in food and diet from Mediterranean area. Food Chem. 135: 423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shuaib F. M., Jolly P. E., Ehiri J. E., Jiang Y., Ellis W. O., Stiles J. K., Yatich N. J., Funkhouser E., Person S. D., Wilson C., Williams J. H.2010. Association between anemia and aflatoxin B1 biomarker levels among pregnant women in Kumasi, Ghana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83: 1077–1083. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sibanda L., Marovatsanga L. T., Pestka J. J.1997. Review of mycotoxin work in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Contr. 8: 21–29. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(96)00057-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tchana A. N., Moundipa P. F., Tchouanguep F. M.2010. Aflatoxin contamination in food and body fluids in relation to malnutrition and cancer status in Cameroon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7: 178–188. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7010178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Turner P. C., Loffredo C., El Kafrawy S., Ezzat S., Eissa S. A., El Daly M., Nada O., Abdel-Hamid M.2008. Pilot survey of aflatoxin–albumin adducts in sera from Egypt. Food. Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 25: 583–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Turner P. C., Sylla A., Gong Y., Diallo M., Sutcliffe A., Hall A., Wild C.2005. Reduction of exposure to carcinogenic aflatoxins by postharvest intervention measures inWest Africa: a community-based intervention study. Lancet 365: 1950–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66661-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Udoh J. M., Cardwel K. F., Ikotun T.2000. Storage structures and aflatoxin content of maize in five agro-ecological zones of Nigeria. J. Stored Prod. Res. 36: 187–201. doi: 10.1016/S0022-474X(99)00042-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Uriah N., Ibeh I. N., Oluwafemi F.2001. A study of the impact of aflatoxin on human reproduction. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 5: 106–110. doi: 10.2307/3583204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wagacha J. M., Muthomi J. W.2008. Mycotoxin problem in Africa: current status, implications to food safety and health and possible management strategies. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124: 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.World Health Organization (WHO), 2006. Mycotoxins in African foods: implications to food safety and health. AFRO Food Safety Newsletter. World Health Organization Food safety (FOS), Issue No. July 2006. www. afro.who.int/des

- 78.Wu T. S., Yang J. J., Yu F. Y., Liu B. H.2012. Evaluation of nephrotoxic effects of mycotoxins, citrinin and patulin, on zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50: 4398–4404. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yameogo R. T., Kassamba B.1999. Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin on tropical seeds used for snacks Arachis hypogaea, Balanites aegyptiaca and Sclerocarya birrea. Trop. Sci. 39: 46–49 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang J., Bai F., Zhang K., Bai S., Peng X., Ding X., Li Y., Zhang J., Zhao L.2012. Effects of feeding corn naturally contaminated with aflatoxin B1 and B2 on hepatic functions of broilers. Poult. Sci. 91: 2792–2801. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]