Abstract

Although interpersonal therapy (IPT) has demonstrated efficacy for mood and other disorders, little is known about how IPT works. We present interpersonal change mechanisms that we hypothesize account for symptom change in IPT. IPT’s interpersonal model integrates both relational theory, building on work by Sullivan, Bowlby, and others, and insights based on research findings regarding stress, social support, and illness to highlight contextual factors thought to precipitate and maintain psychiatric disorders. IPT frames therapy around a central interpersonal problem in the patient’s life, a current crisis or relational predicament that is disrupting social support and increasing interpersonal stress. By mobilizing and working collaboratively with the patient to resolve (better manage or negotiate) this problem, IPT seeks to activate several interpersonal change mechanisms. These include: 1) enhancing social support, 2) decreasing interpersonal stress, 3) facilitating emotional processing, and 4) improving interpersonal skills. We hope that articulating these mechanisms will help therapists to formulate cases and better maintain focus within an IPT framework. We propose interpersonal mechanisms that might explain how IPT’s interpersonal focus leads to symptom change. Future work needs to specify and test candidate mediators in clinical trials of IPT. We anticipate that pursuing this more systematic strategy will lead to important refinements and improvements in IPT and enhance its application in a range of clinical populations.

Keywords: Interpersonal therapy, IPT, psychotherapy, interpersonal, mechanisms, mediators

Considering interpersonal therapy’s (IPT’s) extensive evidence base in outcome research (Cuijpers, 2011; Weissman, Markowitz, & Klerman, 2000), researchers have devoted surprisingly little effort to explaining mechanisms of change in IPT. We know that IPT works well for some disorders, but little about why and how. Two factors probably explain this. The first is IPT's pragmatic ethos: IPT practitioners and researchers have been more concerned with how much patients benefit than the clarity of its theoretical model. Its co-architect, Gerald L. Klerman, famously emphasized outcome over process: “If a treatment doesn't help, who cares how it works?” (Markowitz, Skodol, & Bleiberg, 2006). Accordingly, IPT research has focused primarily on efficacy, secondarily on potential moderating factors, but very little on mediating factors. The second factor is IPT's integrative view of therapeutic change. From its inception (Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984), IPT has emphasized a multimodal approach, employing an array of complementary and interdependent, specific and common change factors. Its advocates may have therefore questioned the value of defining IPT by one or a few specific change mechanisms.

Much has changed in the past three decades, however. Practitioners and researchers both within and outside IPT have increasingly sought explication of specific processes of change. It has been suggested that lack of an elaboration of its conceptual approach might impede IPT’s broader dissemination, as some practitioners may not understand what distinguishes IPT from other approaches (Stuart, Robertson, & O'Hara, 2006). Indeed, the importance of understanding how a psychotherapy works surpasses simple intellectual curiosity. Kazdin (2007) outlines several clinically pertinent reasons to study psychotherapy change mechanisms. These include elucidating connections between what happens in therapy and broader treatment effects, optimizing therapeutic change through emphasizing active elements, facilitating thoughtful adaptations of the therapy to real world settings, and identifying theory-relevant moderating factors that permit optimal patient-treatment matching. Understanding change mechanisms and identifying active ingredients in IPT could lead to enhancements through emphasizing and perhaps extending active features while de-emphasizing or removing less potent components.

This paper aims to explain IPT's unique interpersonal focus and the hypothesized specific processes through which its interpersonal work might reduce psychiatric symptoms.1 We shall present these interpersonal change processes in fine grain to clarify the underpinnings and assumptions of IPT's approach and to help better distinguish IPT from other therapies that share an interpersonal focus. We shall focus on four hypothesized change mechanisms: 1) enhancing social support, 2) decreasing interpersonal stress, 3) facilitating emotional processing, and 4) improving interpersonal skills. IPT’s uniqueness lies in its activating all of these mechanisms within a pragmatic, coherent, and affectively-charged focus on a central interpersonal problem (a crisis or predicament) in the patient’s current life. First, we will briefly describe IPT. Then, to provide a clearer foundation for the proposed mechanisms, we will describe IPT’s theoretical model in some detail. We shall then describe the precise role of the interpersonal problem focus within IPT and explain how this framework might activate interpersonal change mechanisms. We then present the four interpersonal mechanisms, which we hypothesize to account for clinical change in IPT. Finally we will consider limitations and propose next steps.

Description of IPT

IPT is a time-limited psychotherapy initially developed to treat major depression (Klerman et al., 1984) and subsequently adapted and studied for treatment of bipolar disorder (Frank et al., 2005), dysthymic disorder (Markowitz, 1996), bulimia nervosa (Fairburn, Jones, Peveler, Hope, & O'Conner, 1993), binge eating disorder (Wilfley et al., 2002), social anxiety disorder (Lipsitz, Markowitz, Cherry, & Fyer, 1999), panic disorder (Lipsitz et al., 2006), and posttraumatic stress disorder (Bleiberg & Markowitz, 2005), among other disorders. IPT has been adapted and studied to treat depression in adolescents (Mufson, Weissman, Moreau, & Garfinkel, 1999), the elderly (Reynolds et al., 1999), and special populations including depressed HIV-positive patients (Markowitz et al., 1998) and patients with mild cognitive impairment (Carreira et al., 2008). Typically administered individually, IPT has been used in group (Wilfley et al., 2002), conjoint (Carter, Grigoriadis, Ravitz, & Ross, 2010), and telephone formats. Its standard approach uses 12–16 weekly sessions to acutely treat a syndrome. Monthly maintenance IPT treatment has demonstrated efficacy in preventing recurrence of major depression (Frank et al., 2007; Kupfer et al., 1992).

The patient and IPT therapist together define a central interpersonal problem (a current crisis or predicament) that serves as the primary treatment focus. The interpersonal problem falls into one of four empirically-derived categories: grief - a complicated bereavement reaction following the death of a loved one, with difficulty reestablishing satisfying interpersonal ties in the absence of the deceased; role transition – an unsettling major life change (e.g., an illness, birth of a child, retirement); role dispute – a conflict, overt or covert, in an important relationship (e.g., with spouse, parent, boss); or interpersonal deficits - social isolation.

IPT has three phases. The initial phase (typically sessions 1–3) includes: a) evaluation – diagnosing the syndrome and any comorbid conditions and conducting the interpersonal inventory – a thorough review of current and past relationships; b) providing the case formulation, which defines the target diagnosis within the medical model, providing the patient with the transitional sick role (Parsons, 1951), and linking this diagnosis to the focal interpersonal problem area; and c) agreeing on the treatment plan. The formulation (Markowitz & Swartz, 2006) provides the interpersonal problem focus through which IPT seeks to activate the change mechanisms described in this report. The middle phase (sessions 4–9) comprises the main work of resolving the interpersonal problem. The final phase (sessions 9–12) involves direct discussion of termination, reviewing improvement, consolidating gains, and anticipating future problems.

An Integrative Therapy

Although the goal of this report is to conceptualize specific change processes related to IPT’s unique interpersonal focus, IPT is an inherently integrative therapy. Klerman, Weissman, and colleagues (1984) devised IPT to optimize and leverage an array of change factors, including “common factors” of psychotherapy (Frank and Frank, 1991). IPT explicitly endeavors to instill hope and enhance expectation for change (Frank, 1971). Through use of the medical model, IPT seeks to create a new narrative for the patient, demystifying and externalizing the current problem as something the patient has rather than a defining aspect of who s/he is. Through use of the sick role, IPT seeks to decrease demoralization and guilt due to past social failures and the burden of current expectations, increase motivation for change (as it is the role of the patient to now get well), and emphatically validate the patient’s current distress. IPT explicitly values and builds on the supportive role of the therapeutic relationship. Common factors are now broadly acknowledged to account for much of psychotherapy’s benefits (Norcross & Wampold, 2011). Indeed, much of the power of IPT's punch may come from how it incorporates and optimizes common therapy factors (Markowitz & Milrod, 2011).

Without wishing to downplay the importance of other, e.g., common change factors such as those listed above, we feel it is important to better articulate change factors and processes that characterize IPT’s unique interpersonal focus and to present their specific constellation and emphasis within IPT. These specific factors might not necessarily work as well if delivered outside of IPT's comprehensive treatment model. We shall refer to these interpersonal change factors as specific because expected effects emerge from IPT’s interpersonal theory and they operate within the unique framework of the interpersonal problem area. However, the distinction between common and specific factors is not always clear (e.g., Butler & Strupp, 1986) as common factors may facilitate specific ones and, conversely, the effect of specific factors (e.g., change in an interpersonal problem) may actually be mediated by common factors (e.g., success experience, mastery). The therapeutic alliance, for example, although best considered a common factor (Krupnick et al., 1996), clearly overlaps with social support, which we address below in the context of IPT’s specific interpersonal thrust.

A Trans-diagnostic Therapy

One final point is vital when considering IPT change mechanisms across syndromes. Although diagnosis-specific in its psychoeducational content and implementation of certain specific strategies, IPT’s primary interpersonal thrust and focal strategies are inherently trans-diagnostic. IPT targets the interpersonal context in which the disorder occurs (a current crisis or predicament) rather than the symptoms, thoughts, and behaviors associated with each particular disorder. Therefore, its therapeutic stance, structure, and focal interpersonal problem areas remain relatively consistent across diagnoses. We propose that the interpersonal change mechanisms below are relevant to all disorders IPT addresses. Relative salience of these mechanisms may differ across disorders; we note below where theory or clinical research has suggested such differences.

IPT’s Interpersonal Model

IPT’s theoretical model is presented in the original IPT manual (Klerman et al., 1984) and in subsequent adaptations. As explained below, IPT utilizes a diathesis-stress model of psychiatric illness and integrates two interpersonal frameworks: relational theory, which provides the basis for connecting relationships with mental health; and research on stress, social support, and illness, which informs IPT’s specific focus on current interpersonal problems.

Relational theory

The interpersonal theory of Harry Stack Sullivan2

Influenced by the integrative psychobiological theory of Adolph Meyer (Meyer & Winters, 1951), Sullivan asserted that: “The field of psychiatry is the field of interpersonal relations; a person can never be isolated from the complex of interpersonal relations in which the person lives and has his being” (Sullivan, 1940, p. 10). Breaking with Freudian drive theory, Sullivan insisted that interpersonal relationships constituted a basic human need and that mental health depended on healthy, intimate connections with other people. In addition to drive-related needs for satisfaction, Sullivan described “security needs,” which operate in the anxiety-arousing interpersonal arena. Influenced by anthropology and social psychology, Sullivan proposed that the self is shaped by “reflected appraisals” in the form of expectations and reactions of others (Sullivan, 1953). Although he considered close, intimate relationships the most crucial social context, Sullivan recognized the importance of wider social contexts (e.g., peer group, school) in determining mental health. Carrying his relational view to its logical conclusion, Sullivan considered the therapist a “participant-observer” (Sullivan, 1954) who necessarily interacted with the patient in a human way, but who also could assume the expert role to help enlighten the patient. Sullivan rejected the therapeutic passivity used to facilitate free association in psychoanalysis. Interested in real events and real interactions, in addition to unconscious processes, he advocated use of direct inquiry (Sullivan, 1954).

Attachment theory

If Sullivan’s clinical wisdom and integration of social science helped shift psychotherapy toward a more relational view, the elegance and breadth of John Bowlby’s attachment theory (1969) solidified this shift and catapulted relational theory to prominence in abnormal, developmental, and social psychology. Nurtured in the British School of object relations (e.g., Fairbairn, 1954; Klein, 1964), Bowlby saw human attachment as a complex, biologically determined system designed to keep the caregiver in safe proximity. He observed that youngsters seek parents as a safe haven in times of distress and proposed that this attachment provides a “secure base” from which to launch independent, goal-oriented behavior. Although attachment has its most vital survival function during infancy, it remains essential throughout life in providing individuals with warmth and nurturance, especially under conditions of stress (Bowlby, 1977). According to Bowlby, secure attachment to the caregiver early in life forms the foundation for later success in interpersonal relationships (Bowlby, 1969, Chapter 5). Bowlby’s notion of “internal working models” (Bowlby, 1973) was later expanded by Ainsworth (1979), who defined “attachment styles” that help determine the quality of later relationships. Noting devastating consequences in young children separated from parents, Bowlby concluded that emotional difficulties such as depression resulted from early attachment difficulties. A wealth of research now links attachment difficulties to a range of psychiatric disorders (Egeland & Carlson, 2004).

Stress and Social Support: From Relational Theory to Problems in Relationships

Sullivan and Bowlby made human relationships central to understanding emotional health and illness. Both believed that development was not fixed from early childhood and that later experiences mattered. However, most adherents to interpersonal psychoanalysis and attachment theory focused principally on how internalized effects of early relationship experiences, e.g., in the form of “parataxic distortions” – the coloring of current interactions based on past experiences (Sullivan, 1953), internal working models (Bowlby, 1973), and attachment styles (Ainsworth, 1979) – influenced later interpersonal problems and thus mental health. To effect meaningful change, the therapist still needed to gain access (e.g., through the transference) to the patient’s internal life and to somehow modify embedded interpersonal tendencies. What emboldened Klerman, Weissman, and colleagues to propose that IPT could reduce disabling symptoms through short-term work on a current interpersonal crisis or predicament? Primarily, it was epidemiologic research on stress, social support, and illness. Further reinforcing IPT’s emphasis were shifts within relational theory, which conceptualized internalized factors as increasingly dynamic and influenced by later experiences (e.g., Egeland & Farber, 1984).

Stressful life events

In the years prior to IPT’s conception, epidemiologic research began to highlight the role of recent stressful experiences, chronic adverse social conditions, and social support in depression and other psychiatric illness. Paykel and colleagues (Paykel et al., 1969) noted that patients reported certain types of stressful events more frequently prior to depressive onset. These included “exit events,” such as death of a loved one or separation from a spouse, and other “negative” events such as physical illness, work problems, or sexual difficulties. Studies have since identified stressful life events as precipitants of bipolar disorder (Hlastala et al., 2000), anxiety disorders (Blazer, Hughes, & George, 1987), and eating disorders (Welch, Doll, & Fairburn, 1997). These research findings corroborated clinicians’ impressions that patients often sought treatment in the context of life difficulties. Interestingly, the importance of life events in psychiatric illness was presaged by Sullivan’s chief inspiration, Adolph Meyer, who in 1919 introduced the detailed life chart to track patients’ important life events and how these influence onset and course of illness (Meyer & Winters, 1951).

Chronic stressful conditions

Although dramatic, acute life events are most obvious, enduring social conditions also matter. Brown and colleagues (Brown & Harris, 1978; Brown, Bifulco, Harris, & Bridge, 1986) linked chronic stressful life conditions in the form of poverty or other adversity to depression in working class women. Weissman and Paykel (1974), showing the high prevalence of marital discord among depressed women, suggested the particular importance of this chronic stressor. Subsequent research corroborated the association of marital discord with depression (Beach, Sandeen, & O’Leary, 1990) and other disorders (Halford & Bouma, 1997). Later research indicated that marital difficulties often preceded depression (Whisman & Bruce, 1999), suggesting that these are not merely consequences of the patient’s depressed mood.

Social support

Brown and Harris (1978) also considered positive, potentially protective features of social connections and the negative impact of their absence. In their study of working class women, the lack of a close confidant constituted a strong risk factor for later depression. Concurrently, Henderson and colleagues (Henderson et al., 1978) associated a poor social support network with neurosis. Numerous studies have since linked low social support to symptoms and diagnosis of depression (Duer, Schwenk, & Coyne, 1988; Monroe, Bromet, Connell, & Steiner, 1986) and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., Stice, 2002).3 Intimate relationships (e.g., marriage) appeared an especially important source of support (Coyne & DeLongis, 1986).

Social support may buffer the negative effects of stress and adversity (Cohen & Wills, 1985) or act as an independent positive factor promoting psychological health (Overholser & Adams, 1997). Conversely, lack of social connection or loneliness may constitute a stress in its own right (Cacioppo et al., 2002). Loneliness is a risk factor for depression (Green et al, 1992) and other psychiatric disorders (Rotenberg & Flood, 1999), findings that are clearly consistent with the lifelong needs for intimacy and attachment described by Sullivan and Bowlby.

The Reciprocal Relationship of Disorder and Interpersonal Context

Although research on stress and social support suggested a causal role for interpersonal context, IPT views the relationship between psychiatric disorders and interpersonal problems as reciprocal. Clinicians observed, for example, that depressed patients often evoked strong reactions in others, including therapists. Psychoanalysis viewed this phenomenon unsympathetically, interpreting it, e.g., as evidence of the patient’s veiled hostility (Bonime, 1976). Coyne (1976), however, proposed an interactional model consistent with an interpersonal framework, wherein the individual’s depressed mood leads her to seek reassurance from a loved one yet leaves her unable to accept this reassurance. This creates a vicious interactive cycle leading to increased frustration with and, ultimately, distancing from the depressed individual (Coyne, 1976). This increases isolation and decreases social connections for the depressed person, which contributes to perpetuating the depressed state. Interactional models have been proposed for other disorders such as social phobia (Alden & Taylor, 2004). IPT endorses this interactional view, seeing not only other people but the disorder itself as an important, contributory character in the current interpersonal drama. In the context of a disorder, such as depression, it is unfair to blame the patient for the current predicament and premature to diagnose negative personality characteristics until the disorder has remitted.

IPT’s Diathesis-Stress Model: Precipitating and Maintaining Factors

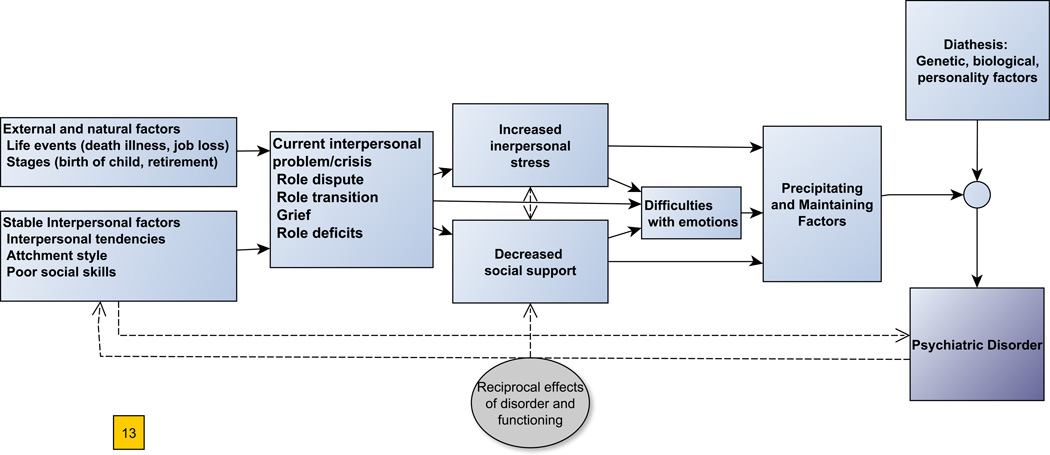

As evidence of genetic and biological etiologic factors mounted for many psychiatric disorders, diathesis-stress (or vulnerability-stress) models emerged that considered both internal, constitutional factors and external, environmental factors causal (Meehl, 1962). The diathesis-stress model shifted the paradigm in psychopathological theories. Whereas early psychoanalytic theories ventured comprehensive etiological models to explain why particular individuals developed symptoms, the diathesis-stress view presumed multiple causes. Accepting that biological factors figured prominently in diathesis, IPT focused on the stress side of this model, seeking to identify psychosocial factors in the form of life events or interpersonal predicaments that precipitated and maintained psychiatric illness, primarily by increasing interpersonal stress and undermining social support (Figure 1). Although stressful life events and challenging social conditions, highlighted by Paykel, Brown, and others, could not fully explain the etiology of depression, they could explain why, given biological and other vulnerability factors (diathesis), a depressive episode might develop at a particular time, persist longer, or recur sooner. Substantial evidence now supports this diathesis-stress model for major depression (Monroe & Simons, 1991) and other psychiatric disorders (Hankin & Abela, 2005). Recent research has begun to elucidate how environmental and biological factors interact to influence course of illness (e.g., Caspi et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

IPT Model of Interpersonal Problems as Precipitating and Maintaining Factors in Psychopathology. External and developmental factors, along with stable interpersonal tendencies, contribute to development of a central interpersonal problem in one of the four areas. This problem increases interpersonal stress and undermines social supports, which, partly through difficulties with emotions, precipitate and maintain episodes of psychiatric disorder. Bi-directional line portrays the reciprocal effects of psychiatric symptoms and interpersonal problems and patterns.

Stressful life events and conditions precipitate and maintain psychiatric disorders through biological pathways including neuroendocrine (e.g., Shekhar, Truitt, Rainnie, & Sajdyk, 2005), immune dysregulation (Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002), inflammatory (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011), and epigenetic effects (Toyokawa, Uddin, Koenen, & Galea, 2011). Stressful events and conditions may lead to behavioral changes, such as alteration of activity level and sleep, which increase risk of depression and other disorders (Riemann, 2003; Strawbridge, Deleger, Roberts, & Kaplan, 2002). The loss or diminution of positive, protective effects of social support on mental health (summarized below under social support) likewise precipitate and maintain psychiatric disorders.

As Figure 1 shows, a stressful life event, a particular developmental stage, or challenging ongoing conditions, in the context of stable interpersonal factors, such as insecure attachment style or deficits in interpersonal skills, may become an interpersonal problem – a prominent crisis or predicament in the patient’s interpersonal context. The interpersonal problem meaningfully increases interpersonal stress and impedes social support, which, in the context of vulnerability factors (diathesis), precipitate and maintain symptoms. Life transitions, conflicts, personal losses, and the stress these create, further generate strong negative emotions, while lack of social support undercuts adaptive means of processing and regulating these emotions; this may further affect mood and symptoms. Reciprocal effects of the disorder (dotted line) might worsen aspects of the problem itself (e.g., increasing irritability within a marital conflict) and hinder adaptive interpersonal behavior (e.g., decision-making, assertiveness) needed to resolve this problem.

The Interpersonal Problem as Therapeutic Framework and Change Process

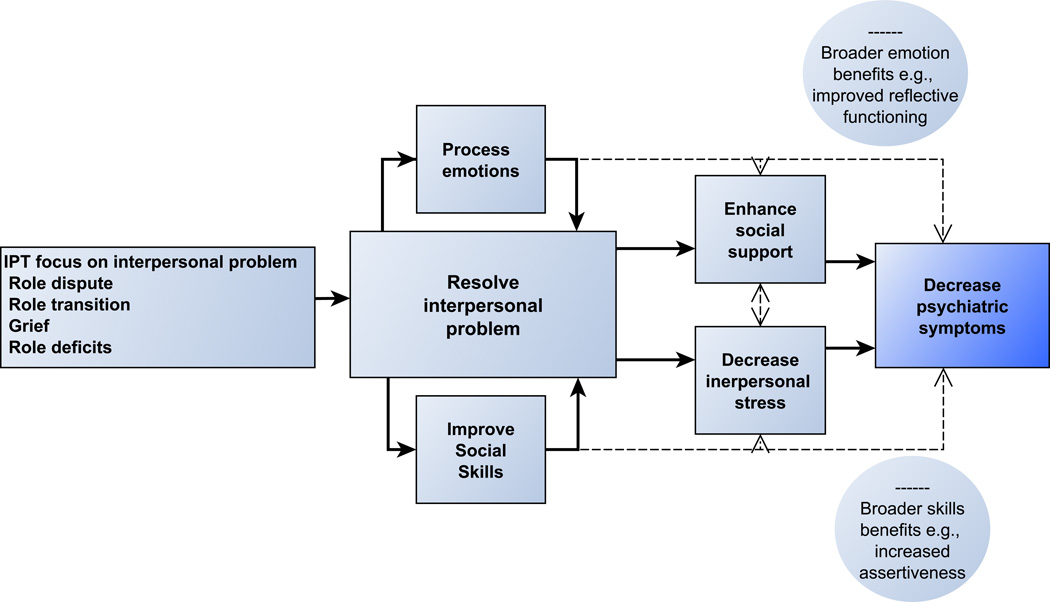

Recognizing the importance of the interpersonal context in precipitating and maintaining psychiatric disorders, IPT focuses therapy on a central interpersonal problem in the patient’s life and proposes that resolving this crisis constitutes the central interpersonal change process (Figure 2). Following basic elements of psychotherapy change as outlined by Doss (2004), we distinguish here between a) therapy change processes – interventions or aspects of the therapy itself; b) client-interpersonal change process – proximal changes in client behaviors, experiences, and, for IPT, interpersonal context, as a direct result of these interventions; and c) change mechanisms – intermediate, theory-driven steps that explain the association of these processes with outcome.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized Interpersonal Change Mechanisms in IPT. Solid lines indicate IPT’s primary target of resolving the interpersonal problem, which involves processing emotions and enhancing/adapting interpersonal skills. Resolution of the problem enhances social support and decreases interpersonal stress, which reduce symptoms. Dashed lines indicate additional, broader, lasting benefits in handling emotions and interpersonal skills expected to occur with IPT.

IPT helps the patient to resolve the interpersonal problem (crisis or predicament) by altering the problem itself, changing her/his relationship to the problem, or both. This framework fundamentally distinguishes IPT from many other therapy models, which identify the problem within the patient and seek to change some problematic aspect of the patient’s personality, attachment style, schemas, etc. IPT attempts not to fix the patient, but to help the patient fix the problem in the interpersonal context and their relationship to this problem, thereby helping her to enhance his life situation and to recover from the psychiatric syndrome. Along the way, the patient may well learn to better understand and manage emotions and interpersonal encounters, more generally, and build interpersonal skills, but the primary goal is resolving the current problem and reducing symptoms. Treatment addresses the patient's problematic patterns and tendencies insofar as they contribute to the current problem or impede progress toward its resolution. For example, IPT might address a patient’s perfectionism in the context of a role dispute, in which perfectionism contributed to the conflict or prevented steps toward resolution, but this same characteristic might have less relevance to IPT work on another problem such as grief. The IPT therapist might also attribute current perfectionism to mood-dependent vulnerability, rather than to the patient’s personality.

Although personality and other internal factors may contribute to developing interpersonal problems (e.g., Hammen, 2005), these factors do not explain all the variance. Often the patient is a victim of circumstances (e.g., the untimely death of a loved one, a chronic medical illness) or stuck in a noxious predicament (e.g., a loveless marriage, a dead-end career) and needs the therapist's help to become unstuck. Alternatively, once-adaptive aspects of the patient’s interpersonal style (e.g., stubborn independence) may now poorly fit a new interpersonal role. Again, the psychiatric disorder may itself contribute to the interpersonal crisis and impede progress towards its resolution. Assessing stable personality traits in the context of an impairing syndrome is difficult. IPT takes a wait-and-see approach to problems in the patient's personality or attachment style. It thus avoids the traditional focus on problematic patterns, which can potentially demoralize the patient and risks invalidating the patient’s experience by emphasizing what the patient is doing wrong rather than their experience of injury and distress (Bateman & Fonagy, 2010).

The interpersonal problem encompasses not only the specific focal situation but other interpersonal factors influencing the patient’s experience of the problem. For example, marital conflict (role dispute) might sometimes persist, but the patient will experience it very differently (as less stifling, humiliating, angering) once s/he has stopped accepting all the blame, has begun to consider effective options for response, and has obtained previously untapped support from a close friend. The limitations and physical pain of a chronic illness (role transition) might linger, but the patient may feel better after expressing associated anger and sadness more openly, becoming more forgiving and accepting of this new reality, and altering interpersonal patterns (e.g., turning more easily to others for help), thus now feeling less isolated, more socially competent and valuable. In such cases the interpersonal problem is, at least partially, resolved, even though tangible aspects of life challenges and sources of distress may persist.

Reinforcing the importance of this therapeutic frame, research indicates that IPT has greater efficacy when the therapist maintains focus on the interpersonal problem area (Frank et al., 2007; Frank, Kupfer, Wagner, McEachran, & Cornes, 1991). Selecting and defining the interpersonal problem is no simple matter, however. Encouragingly, IPT therapists tend to agree on possible problem areas and on which problem they would choose as a therapeutic focus for specific patients (Markowitz et al., 2000). Yet relatively little research has examined the degree of change in the focal interpersonal problem or how such change is related to symptoms reduction.

The Interpersonal Psychotherapy Outcome Scale (IPOS; Markowitz et al., 2000; Weissman, Markowitz, & Klerman, 2007) asks to what degree the patient feels that he or she has solved the focal interpersonal problem in IPT. Using the IPOS, Markowitz and colleagues (Markowitz, Bleiberg, Christos, & Levitan, 2006) found that symptomatic improvement in dysthymic disorder and PTSD correlated with patients’ ratings of degree of resolution of the interpersonal problem. Although a beginning, the IPOS has limitations. It does not assess the salience, initial severity, or broader context of the interpersonal problem. Furthermore, treatment satisfaction or wish for social approval may confound the patient’s view of therapeutic progress. To more systematically assess a broader context of interpersonal problems, the Interpersonal Problems Questionnaire (IPQ; Menchetti et al., 2010) assesses: a) interpersonal relationships; b) broader aspects of social life; and c) recent major life events. This scale, however, fails to track change in the focal interpersonal problem as the IPOS does. No IPT study has combined these approaches, nor tested the IPOS or IPQ as mediators of symptom change in IPT.

From Interpersonal Framework to Mechanisms of Change

How does resolving the interpersonal problem alleviate psychiatric symptoms? To date, IPT has not sufficiently elaborated specific mechanisms to account for this change. We propose that the framework and process of resolving the interpersonal problem affects psychiatric symptoms through the following mechanisms: 1) enhancing social support, 2) decreasing interpersonal stress, 3) facilitating emotional processing, and 4) improving interpersonal skills. As Figure 2 illustrates, we propose that resolving the interpersonal problem in IPT enhances social support and decreases interpersonal stress, which can be conceptualized as the generalized effects of resolving the problem on the patient’s life. Resolving the problem necessitates confronting and processing emotions and expressing these in the interpersonal context. Finally, overcoming a crisis or predicament, and breaking negative interactional cycles, requires adapting and improving interpersonal skills.

These two latter factors primarily facilitate the resolution of the interpersonal problem, thus affecting symptoms, secondarily, through changes in social support and stress. At the same time, engaging these latter mechanisms in service of the target problem expectably yields broader benefits which might also affect symptoms (dashed lines). Dotted lines from symptoms to the left depict reciprocal effects of (decreases in) symptoms on the interpersonal context and the interpersonal problem. For simplicity’s sake, we portray primary therapeutic processes and do not depict every effect and interrelationship. For example, social support is thought to decrease symptoms partly through its positive effects on regulating emotions (see below under social support).

Below we describe the hypothesized change mechanisms and explain how each mechanism is thought to function within IPT. For the latter, facilitative factors, we shall present expected, broader effects. Although tests of mediation in IPT are scarce, we shall present relevant empirical research for each mechanism.

Interpersonal Mechanism 1: Enhancing Social Support

The term “social support” evokes negative reactions in psychotherapists to whom it suggests concrete or superficial aspects of human relationships. Indeed, as social support implies some resource another person provides (Cohen & Syme, 1985), this term appears to ignore the inherent importance of intimate human connection proposed by Sullivan and Bowlby. However, social support encompasses the gamut of interpersonal resources, from the availability of a friend to lend money to the warm embrace of an intimate partner. This need for human connection can also be conceptualized, following Bowlby, as reflecting an ongoing need for attachment. However, the term attachment refers simultaneously to the internalized capacity for making connections, the individual’s relational style, and the mother-infant bonding experience. As such, this term might obscure IPT’s radical departure from relational theory’s early focus on internalized aspects of early experiences. In our view, social support better captures IPT’s focus on all aspects of the current relational context, including the individual’s functional role within society. Indeed, some social support researchers have presented IPT as a social support-oriented intervention (Brugha, Stansfeld, & Freeman, 2008). However, only recently have theoretical discussions of IPT emphasized social support per se (Champion, 2012; Lipsitz, 2009) and IPT research has yet to examine social support as a mediator of change.

Although the consequences of support deprivation may seem self-evident (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), theorists have outlined specific benefits of social support that might help explain effects on mental health (Thoits, 2011). These range from social influences on health behaviors (exercise, nutrition, sleep, etc.) emerging from social comparison and positive peer pressure to companionship itself, which produces positive affect (Thoits, 2011). Two examples are interpersonal emotion regulation and social roles.

Interpersonal emotion regulation

Emotional dysregulation is a feature of many psychiatric disorders (Gross, 2009). Although much recent research focuses on internal (e.g., cognitive) regulation capacities and processes, emotions are largely processed and regulated within relational systems (Lakey & Orehek, 2011; Marroquín, 2011). Other people may aid emotion regulation on a cognitive level through, e.g., reappraisal (Lakey & Orehek, 2011), or on a more directly emotional-relational level through holding (Winnicott, 1965) and containment (Bion, 1995) – the soothing and stabilizing effect of an empathic, emotional, maternal embrace within a supportive relationship. Relational theory suggests that under positive conditions the developing child gradually internalizes the soothing function of the caretaker (e.g., Winnicott, 1965). Adults continue to rely on loved ones for this holding function (e.g., Greenberg & Johnson, 1988).

Social roles, self-esteem, and self-efficacy

Social roles (husband, father, caring son, accountant, friend, church congregant, etc.) provide behavioral constraint and regulation through social obligations, routines, and expectations (Durkheim, 1897/1951), helping to stabilize mood states. They also provide a sense of meaning and purpose deriving from having a place and function (mattering) within society. Social roles provide myriad predictable, interactive tasks to fulfill, which can increase self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977) and success experiences which enhance self-esteem.

For most adults, the marriage/life partner relationship holds unique importance and moderates effects of other sources of support (Coyne & DeLongis, 1986). The quality of the bond, measured along dimensions of relationship satisfaction, intimacy, trust, responsiveness, commitment, and conflict, may determine experience of support versus discord (Reis & Collins, 2000). Weissman and Paykel’s detailed portrayal of marital problems in depressed women (1974) anticipated epidemiologic findings that women in unhappy marriages were 25 times more likely to be depressed than those in happy marriages (Leaf, Weissman, Myers, Holzer, & Tischler, 1986). Numerous studies have since corroborated the association between marital problems and depression and other psychiatric disorders (Whisman, 2007). As psychiatric symptoms reciprocally contribute to marital problems, this association is admittedly complex (Rehman, Gollan, & Mortimer, 2008).

Social Support within the IPT Interpersonal Problem Areas

Each IPT interpersonal problem area reflects a difficulty in the patient's current environmental context that disrupts and undermines social support. Role transitions (e.g., divorce, retirement, illness) are life changes that interrupt or interfere with established social ties. A patient who has given birth to a child or is dealing with a challenging illness may temporarily lose her social bearings and sources of support. Role disputes reflect conflict in a primary relationship that might otherwise be an important source of social support. Besides generating stress, a dispute compromises the supportive function of this relationship. Grief denotes the loss through death of a primary social tie that may have previously provided support, belonging, and social value. Grief may also impede developing alternative and compensatory ties and may emotionally distance the individual from others who, for example, do not share this grief. Interpersonal deficits reflect general isolation, and lack of interpersonal connection and support (Weissman et al., 2007). In all of these cases resolving the interpersonal problem should meaningfully improve social support for the patient in a more general sense.

Enhancing Social Support in IPT

In focusing on resolving a prominent interpersonal problem as a means of enhancing social support, IPT differs from supportive therapy (e.g., Pinsker, 2002) and from systematic social support interventions, which seek to directly improve support more globally. IPT further differs from some relational psychoanalytic therapies, which view supportive holding as a primary function of the therapist (e.g., Winnicott, 1965), believing that this will ultimately improve the patient’s internal emotion regulation. IPT views the therapeutic relationship as an important transitional source of social support, providing a reassuring, safe connection during a difficult crisis, filling the gap created by a lost relationship, or reducing tension in a conflict-filled relationship. IPT emphasizes the evanescence of this time-limited role and uses the therapeutic relationship as a springboard to develop, strengthen, renew, and deepen outside relationships. The therapist actively encourages the patient to seek connections and accept support outside of therapy, helping them engage and rely more on others, e.g., through communication analysis.

Some additional features of IPT help patients to more effectively obtain and more readily accept social support. Stroebe and Stroebe (1996), in a review, concluded that people offer social support more readily when they perceive: 1) that the individual has a clear need, 2) the problem is not the individual’s fault, and 3) the individual is trying to overcome the problem. In providing the medical model and the sick role, IPT emphasizes that the patient suffers from a treatable psychiatric disorder not of his or her own making, has an acute and justified need for support, and by seeking treatment is mobilizing to help him/herself, thus hopefully inviting patience and empathy from others, thus helping the patient to obtain support more effectively. Some evidence indicates that receiving social support can itself cause distress, perhaps due to feeling guilty and demoralized by dependency (Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000). The medical model and sick role offer the patient herself a forgiving explanation for their temporarily increased need for support, helping her to avoid feelings of demoralization.

To highlight chronic challenges of discomfort with social roles and low social self-efficacy in social phobia, IPT’s adaptation for this disorder identified role insecurity as an alternative interpersonal problem focus (Hoffart, Borge, Sexton, & Clark, 2009). IPT for eating disorders views difficulties with self-efficacy and self-esteem, linked to difficulties in the relational context, as closely linked to problematic eating behaviors (Murphy, Cooper, Hollon, & Fairburn, 2009; Rieger et al., 2010).

Research on Social Support

As noted above, social support is thought to influence physical and mental health, either directly or as a buffer against the negative effects of stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985). In one study of maintenance IPT for depression, the index episode was associated with stressful life events (Harkness et al., 2002), but during subsequent, monthly maintenance IPT treatment, the association between stress and depressive symptoms no longer held. This raises the possibility that IPT might have ameliorated social support, thus buffering against stress. Unfortunately, this study did not measure social support.

Examining regulation effects that might be tied to social roles, Frank and colleagues examined social Zeitgebers (time-bound daily routines) in patients with bipolar disorder. They found that Zeitgebers protect against bipolar episodes (Frank, Swartz, & Kupfer, 2000). Further, they found that improving social rhythm regularity mediated the protective effect of interpersonal social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) against new episodes of bipolar disorder (Frank et al., 2005).

In the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project (TDCRP), Kung and Elkin (2000) found improved marital adjustment after 16 weeks of treatment was associated with better outcome in depressive symptoms and social adjustment at follow-up. Yet in that study, CBT, although less likely to identify marital adjustment as a specific goal of therapy, yielded improvements in marital adjustment similar to those of IPT. This may be because change in martial adjustment was measured only post-treatment, after symptomatic change had already occurred. Thus this measure most likely reflected a result rather than a mediator of symptomatic recovery.

Interpersonal Mechanism 2: Decreasing Interpersonal Stress

Interpersonal stress is sometimes conceptualized as the inverse of social support. However, effects of negative interpersonal experiences extend beyond lack of social support (Rook, 1984) and present different clinical challenges. We therefore conceptualize (reducing) interpersonal stress as a separate change mechanism. As presented above in IPT’s Interpersonal Model, IPT’s focal problems were chosen as major life events or chronic stressful conditions empirically linked initially to depressive episodes and later to other psychiatric disorders. Lesser stressors (daily hassles) also contribute to psychiatric symptoms and might mediate effects of major stressors (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981). Another source of interpersonal stress, highlighted by Brown and Harris (1978), involves enduring stressors such as single parenthood, family conflict, or minority status.

Although not all prominent stressors are interpersonal, most are. Stressful interpersonal experiences provoke greater emotional distress than impersonal stressors (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989), a pattern that also holds for trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder (Dorahy et al., 2009). Yet impersonal stressors often have meaningful interpersonal effects. A job loss or illness causes stress not only because of diminished finances or compromised physical health, but because such events undermine the individual's social role and relationships.

Addressing Interpersonal Stress within the Interpersonal Problem Areas

Each IPT interpersonal problem area constitutes an interpersonal stressor for the patient; hence a primary goal is to reduce the patient’s stress experienced in this context. The death of a loved one (grief) is among the most stressful of life events (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). IPT seeks to facilitate the grieving process so that this loss eventually becomes less distressing. For role disputes, IPT attempts to lessen stress associated with ongoing friction, anger, shame, helplessness, and alienation that may occur in a discordant relationship. This may involve an intermediate stage of heightening the conflict so that the patient can express negative feelings more openly and explore options for renegotiating the relationship. Role transitions strain the individual's existing modes of adaptation, as the earliest definition of stress suggests (Selye, 1955). This may occur with seemingly “positive” events, such as marriage, the birth of a baby, starting college, or a promotion. IPT seeks to help the patient reduce the stress of the transition by acknowledging and mourning losses, clarifying positive and negative aspects, identifying and processing strong feelings about the transition, and modifying interpersonal patterns. In interpersonal deficits, lessening the stress of loneliness and isolation (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003) becomes the primary goal.

Horowitz (2004) proposed two categories of interpersonal stressors involving different interpersonal needs. Some stressors may reflect problems related to communion, interrupting stable attachments and leaving the individual feeling lonely, rejected, and disconnected. This might typify role transitions such as a romantic breakup, “empty nest,” or relocation. Other stressors, challenging the need for mastery, make the individual feel helpless, inferior, and a failure (Horowitz, 2004). This category may better capture role transitions such as unemployment or illness. Often, both aspects are intertwined in the context of the interpersonal problem.

Decreasing Interpersonal Stress in IPT

Numerous psychological interventions seek to reduce stress by helping the patient change his/her patterns of cognitive processing (cognitive therapy), re-deploy attention to the present (mindfulness training), or induce relaxation (e.g., applied relaxation). These have the common goal of helping the patient better manage and cope with challenging situations. As described above, IPT views the interpersonal problem as the primary culprit for current feelings of stress. It seeks to decrease stress by changing stressful aspects of this reality or the patient’s relationship to it. Additional features of IPT, such as the medical model, the sick role, and the therapeutic relationship, also seek to decrease stress by temporarily alleviating social burdens and expectations.

Some types of stressful events or situations appear to have a closer etiologic association with certain psychiatric disorders, such as exit events with depression (Paykel et al., 1969); role transitions leading to social rhythm disruptions in bipolar disorder (Malkoff-Schwartz et al., 1998); or conflicts in panic disorder and agoraphobia (Kleiner & Marshall, 1987). IPT for these disorders may be more likely to focus on these specific types of stressful events.

Research on Interpersonal Stress

The role of prominent stressors as precipitating events seems to differ across episodes of psychiatric disorder. In depression, major life events are more prominently associated with first than with subsequent episodes (Monroe, Rohde, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1999). This diminishing association may be due to a “kindling” effect (Post, Rubinow, & Ballenger, 1986). However, subsequent episodes have been linked to minor life events (Lenze et al., 2008) or chronic adversities (Monroe, Slavich, Torres, & Gotlib, 2007). Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that minor life events may predict depressive recurrence during maintenance IPT (Lenze, Cyranowski, Thompson, Anderson, & Frank, 2008). IPT’s efficacy in forestalling recurrent depression (Frank et al., 2007) may reflect its capacity to address and reduce stress under chronic adverse conditions, not just acutely stressful events. Two such contexts of chronic interpersonal stress are familial expressed emotion (EE; Leff & Vaughn, 1985) and marital conflict.

EE involves high levels of hostility, criticism, and emotional over-involvement, presumptively stressful for the patient (Leff & Vaughn, 1985). High EE is associated with heightened relapse and recurrence rates across psychotic, mood, eating, and post-traumatic stress disorders (Hooley, 2007). Family interventions to decrease EE reduce patient relapse rates (Eisler et al., 2000). Although IPT does not explicitly address EE, it attempts to reduce interpersonal conflict, most explicitly in role disputes. IPT psychoeducation provides a forgiving perspective through which intimates can view the patient’s current problems. Like EE theory, IPT emphasizes that interpersonal difficulties are interactional. Noting an association between illness attribution and interpersonal factors in relatives of elderly depressed patients, Hinrichson and colleagues (2004) proposed that better understanding of EE may inform interventions for caregivers. Studies have examined the moderating effects of EE on cognitive behavior therapy (Chambless & Steketee, 1999), but not on IPT. Interestingly, a recent study of IPT for adolescents found IPT more efficacious for teens who at baseline had a prominent conflict with a parent (Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Jekal, & Turner, 2010), raising the possibility that lowering EE may lead to improvement.

Beach, Sandeen, and Leary (1990) describe how marital discord not only undermines social support, but directly increases stress, especially through increased hostility. Marital disputes, measured with the marital adjustment subscale of the Social Adjustment Scale, predicted worse outcome in one IPT study (Rounsaville, Weissman, Prusoff, & Herceg-Baron, 1979). However, couples interventions targeting marital discord have been found to decrease symptoms of depression and other psychiatric diagnoses (Lebow, Chambers, Christensen & Johnson, 2011). An IPT conjoint (couples) format exists but unfortunately has received little research attention (Foley, Rounsaville, Weissman, Sholomskas, & Chevron, 1989).

Interpersonal Mechanism 3: Processing Emotions

Emotions are the primary language of interpersonal relationships, and central tasks in confronting and surmounting interpersonal problems in IPT comprise identifying, processing, and expressing emotions that arise. Early psychoanalytic theory viewed the very expression of emotions (“catharsis”) as curative, relieving internal tension created by repression (Freud & Breuer, 1955). Some conceptualizations of depression focused on repressed anger or “anger turned inward” (Abraham, 1911; Rado, 1928), implying that expressing anger openly might help alleviate depression.

Although some research supports this cathartic benefit for emotions such as aggression (e.g., Verona & Sullivan, 2008), contemporary emotion models emphasize the interplay of emotions and other factors. Emotion focused therapy (EFT) identifies emotion schemes – internalized emotional structures influenced by past interpersonal experiences – as major sources of distress and psychopathology (Greenberg & Watson, 2006). Mindfulness-based approaches propose that open, non-evaluative processing of emotions can alter cognitive appraisals, which are thought to worsen suffering (Lynch, Chapman, Rosenthal, Kuo, & Linehan, 2006). Mentalization-based treatment (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004) conceptualizes some psychiatric disorders as linked to confusion in interpreting emotional states. Its goal is to help the patient achieve reflective function – the ability to understand one’s own and others’ emotional states and to clearly distinguish them. This capacity putatively helps the patient to better modulate emotional responses (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004).

Processing Emotions within the Interpersonal Problem Areas

Interpersonal losses, changes, and conflicts generate varied, powerful emotions that individuals with depression and other psychiatric disorders may have difficulty tolerating, understanding, and expressing (Markowitz & Milrod, 2011). The individual in a role dispute, feeling frustrated and angry, may need help accepting the legitimacy and appropriateness of these feelings, understanding their interpersonal meaning (e.g., anger often means someone is bothering you, failing to respond to you); and then expressing them, perhaps initially in sessions and role plays with the therapist, and later directly to the relative, partner, friend, or boss. Someone experiencing a role transition, such as adjusting to a serious illness, may need to mourn the old role and adjust emotionally to the new role by increasing awareness, acceptance, and ability to express uncomfortable feelings of sadness, anger, shame, and guilt. The therapist seeks to help the patient first acknowledge the presence and depth of these feelings, then verbalize them, all the time accepting their legitimacy, validity, and social utility. In complicated grief, emotional processing may be a central thrust of IPT as the patient needs help processing the loss before s/he can reinvest in existing connections or establishes new ones.

Processing Emotions in IPT

IPT distinguished itself from Beck’s cognitive therapy partly through its emphasis on affect (feeling states) rather than cognitions or evaluative aspects of emotions (Elkin, Parloff, Hadley, & Autry, 1985). IPT invites, accepts, and validates affective expression, while emphasizing the interpersonal character and effects of emotions. Although its goal of processing emotions leads to overlap with subsequently developed emotion oriented therapies such as EFT and mentalization, IPT engages emotional processing primarily in the service of confronting and resolving the focal interpersonal problem. Emotion work is integral to adapting to interpersonal challenges, reacting to interpersonal stress, and overcoming conflicts. Again, IPT focuses on fixing the problem in the interpersonal context rather than an underlying problem in the patient. IPT further presumes that the psychiatric disorder may impede emotional processing and therefore resists drawing conclusions about lasting emotional handicaps which characterize personality pathology. By facilitating resolution of the problem area, emotional processing may contribute to enhanced social support and decreased stress (Figure 2).

Broader Benefits of Emotional Processing

Although the primary goal of processing emotions in IPT is to facilitate resolution of the interpersonal problem, intensive work on difficult feelings; their acceptance and consistent validation in a close, supportive therapeutic relationship; and coaching on their constructive expression outside the therapy might expectably yield additional, broader lasting, emotional benefits for many patients. For example, patients should attain greater attunement to and normalization of feelings, and greater ability to express and verbalize such feelings in the interpersonal context (Figure 2, dashed line). Thus, Markowitz and colleagues (Markowitz, Milrod, Bleiberg, & Marshall, 2009) proposed that reflective function (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004), a presumably enduring ability to understand one’s own and others’ emotions, might mediate change in IPT for patients with chronic PTSD who are poorly attuned to their own emotional states.

Research on Emotional Processing

A secondary analysis of emotional factors in the TDCRP found that “collaborative emotional exploration” was rated higher in IPT than in CBT sessions and that this dimension correlated with positive outcome (Coombs, Coleman, & Jones, 2002). However, this study used transcripts from a selected sample of sessions, and a coding system that overlapped problematically with alliance factors. State of the art assessment of emotional processing includes physiologic measures of arousal and ratings from taped sessions using validated coding systems. For example, Greenberg and Malcolm (2002) found that patients who experienced more intense emotions in EFT, as indicated by greater physiologic arousal, achieved greater problem resolution.[J14] IPT has yet to conduct such systematic examination of emotional factors.

Interpersonal Mechanism 4: Improving Interpersonal Skills

Most psychiatric disorders entail difficulties in interpersonal functioning. Although often conceptualized as consequence of psychiatric disorders, such difficulties may also contribute to their development (e.g., Lewinsohn, 1974) and persistence (e.g., Coyne, 1976). Structured social skills training programs have benefitted patients with unipolar depression (Bellack, Hersen, & Himmelhoch, 1981) and social phobia (Stravynski, Marks, & Yule, 1982), among other disorders. However, nearly all psychotherapies seek to nurture and enhance interpersonal skills in less structured ways. Indeed, improving interpersonal functioning ranks among the most universal goals in psychotherapy (Follette & Greenberg, 2005).

In his behavioral model of depression, Lewinsohn (1974) proposed that deficient social skills hindered the ability to obtain positive reinforcement and that inadvertent reinforcement of depressive behaviors served to strengthen them. The deficits model of social phobia proposes that individuals fail to interact with others because they lack social skills, and that this avoidance eventually generates increased anxiety and social phobia (Curran, 1977). Research has not provided clear support for such apparent causal effects (Hokanson & Rubert, 1991); rather the association of skills and symptoms appears complex and reciprocal. Some interpersonally oriented theories focus on personality-based interpersonal patterns, analyzing the structure and sequence of interactions and how these might increase vulnerability to psychopathology (Anchin & Kiesler, 1982). Within this broad framework, Horowitz developed the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, 2004), which assesses problematic interpersonal patterns along various dimensions.

Addressing Interpersonal Skills within the Interpersonal Problem Areas

IPT seeks to improve interpersonal skills primarily within the framework of the focal interpersonal problem area. In a role dispute this may include learning to communicate feelings more directly, using constructive assertiveness, or learning to diffuse tension. In role transitions, IPT focuses on skills needed to better adapt to the new interpersonal role. For a patient dealing with an illness, this may involve expressing his or her needs to others or setting limits with a caring but intrusive caretaker. For a retiree, this may include learning to initiate social contacts and activities. In Grief interpersonal skills may include independent steps previously managed by the deceased. Interpersonal skills such as self-disclosure and next steps in building friendships, may play a more central role in interpersonal deficits, for which developing and practicing skills through role play may be essential to overcoming social isolation.

Improving Interpersonal Skills in IPT

In contrast to behaviorist deficit models (e.g., Lewinsohn, 1974), IPT presumes that patients generally possess latent social skills but have trouble employing these effectively due to interference from the current crisis, the psychiatric episode, or both. There is generally no need for the systematic, general didactic skills training behaviorally oriented programs provide. The IPT therapist identifies specific skills needed to address an interpersonal predicament or to adapt more effectively to a new role. IPT addresses communication skills using communication analysis and role play while preserving focus on the specific interpersonal problem. IPT considers social skills essential to successful resolution of the current interpersonal crisis or predicament. Improving social skills may therefore yield symptomatic change indirectly, through improved social support and decreased stress (Figure 2). Of course, the hope is that acquired skills will endure and generalize to other situations.

Some IPT adaptations have emphasized interpersonal skills to a greater degree based on deficits in specific populations. For example, reflecting the developmental context, IPT for adolescent depression places greater emphasis on developing social skills, including perspective-taking skills and negotiating parent-child tensions (Mufson et al., 1999). Likewise, group IPT for binge eating disorder more consistently attends to constructive assertiveness and other social skills wanting in this population (Wilfley, 2000).

Broader Benefits of IPT Work on Interpersonal Skills

In addition to resolving the interpersonal problem, IPT work on interpersonal skills is expected to generalize to other contexts. For example, the individual who has learned become more constructively assertive in setting limits with an intrusive parent (“You’re bothering me; I need some space”) may apply this skill in other contexts. Along these lines, maintenance IPT seems to ameliorate habitual (Cluster C) personality features in recovered depressed patients (Cyranowski et al., 2004). Thus improving interpersonal skills in IPT has expected broader benefits (dashed line in Figure 2), possibly through reinforcement (Lewinsohn, 1974) or interactional effects (Coyne, 1976). Improved interpersonal skills can help maintain social support and decrease stress so the patient can avoid being derailed by interpersonal problems in the future.

Research on Improving Interpersonal Skills

Change in interpersonal patterns may be the most thoroughly researched of potential mediating factors in IPT. Some studies have examined whether stable interpersonal patterns as measured by the IIP mediate change in IPT. Results have been inconsistent, but have generally not shown that IPT yields more IIP change than other treatments, nor that IIP change mediates symptomatic change in IPT (Hoffart et al., 2009; Stangier, Schramm, Heidenreich, Berger, & Clark, 2011). This may be because the IIP measures general interpersonal tendencies, such as “assured” vs. “submissive” or “cold” vs. “warm”, whereas IPT targets interpersonal patterns as they impinge on the interpersonal context and the patient's experience of it. Second, as state mimics trait, the IIP may conflate features of the current psychiatric episode with more stable interpersonal traits.

Several IPT studies have examined a related construct, social adjustment, mostly using the Social Adjustment Scale (SAS; Weissman et al., 1978). Social adjustment may inversely correlate with interpersonal problems measured by the IIP (Vittengl, Clark, & Jarrett, 2003) and it may protect against psychopathology (Barton, Miller, Wickramaratne, Gameroff, & Weissman, 2012). The NIMH TDCRP investigators hypothesized that IPT, thought to treat depression by alleviating interpersonal problems, would benefit patients with more severe social maladjustment; whereas CBT, presumed to treat depression by addressing problematic cognitions, would have greater benefit for patients with more cognitive vulnerabilities (Imber et al., 1990). Results contradicted these hypotheses (Imber et al., 1990), challenging assumptions regarding deficit-driven models of intervention and suggesting that therapies may work best building on areas of relative strength. However, as the SAS measures actual performance in different roles, it may be difficult to disentangle possible vulnerability factors from consequences of the disorder.

Summary and Future Directions

Building on foundations of relational theory and epidemiologic findings regarding life events, stress, social support, and course of psychiatric illness, IPT proposes that psychiatric disorders are precipitated by, maintained by, but also contribute to interpersonal crises and predicaments. IPT seeks to relieve symptoms by targeting and resolving a focal interpersonal problem, in the process activating various interpersonal change factors. We propose that resolving the interpersonal problem leads to symptom change by: 1) enhancing social support and 2) decreasing interpersonal stress. Resolving the interpersonal problem entails 3) processing emotions that arise in this context, and 4) improving interpersonal skills, mechanisms which once engaged in IPT also yield broader benefits. None of these change mechanisms defines IPT, nor is any unique to IPT, nor may all factors have equal importance in a given treatment. IPT’s uniqueness lies in seeking to activate all of these 1) in a coherent, plausible therapeutic frame, defined by a current interpersonal crisis or predicament in the patient’s life; and 2) in a time-limited, diagnosis-focused treatment, which leverages common therapeutic change factors. Systematic consideration of specific interpersonal change factors is necessary to optimize IPT and its application to clinical problems. Surprisingly little research has tested which if any of these factors mediate change in IPT. We hope that this conceptualization and review will spur research on mediators and mechanisms of change in IPT. Research findings will help refine and enhance this preliminary model.

We have accentuated the interpersonal problem focus as defining and pivotal for IPT. An implicit assumption is that the focal interpersonal problem has sufficient salience that its resolution will meaningfully improve social support and decrease interpersonal stress in the patient’s every day life. For some cases, presenting a circumscribed problem within an otherwise stable context, this assumption seems clearly justified. For others, wherein therapist and patient must select a single problem from among numerous, pervasive and challenging life circumstances, it is less evident how change in the focal problem (leaving other problems unchanged) will affect overall level and quality of social support and stress. Often, under the rubric of a single focus, patients manage to resolve multiple problems. Resolving the interpersonal problem might be less essential to IPT than we propose, however; this framework might simply provide a premise through which to mobilize the patient to work actively and collaboratively with the therapist, elucidate the connection between interpersonal factors and symptoms generally, and activate other change mechanisms such as increasing self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), sense of mastery (Weinberger, 1995), or self-esteem, generally. IPT studies need to examine 1) how strongly change in the focal problem area correlates with change in overall level of social support and interpersonal stress and 2) whether these changes mediate symptom change.

We have attempted to present a unified model that sees all of these interpersonal change mechanisms as relevant, perhaps to varying degrees, for all four IPT problem areas (role transition, role dispute, grief, role deficits). However, these interpersonal problem areas have somewhat distinct clinical challenges and therapy goals. It is possible that specific IPT problem areas may involve specific change mechanisms to the exclusion of others. In grief, for example, emotional processing is a prominent focus while improving interpersonal skills is less so; the opposite is true for interpersonal deficits. Thus each problem area might require a specific model of change.

IPT researchers need to test which interpersonal mechanisms mediate symptomatic change. To do so, we must first operationalize the proposed mechanisms by identifying candidate mediators and valid approaches to measurement. Studies may then determine, for example, whether symptom change in IPT is mediated by (enhancing) social support and, if so, what type (perceived? actual? in what domains?). Evidence of mediation requires that 1) the mediator correlates with the treatment, 2) the mediator has a main or interactive effect with treatment on outcome, and 3) change in the mediator temporally precedes change in the outcome variable (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002).

Evaluating mediation of change in IPT is challenging for two reasons. First, in contrast to internal change that depends on the patient, resolving interpersonal problems involves intricate interplay between the patient and others. Even as a patient improves, s/he ultimately has limited control over others’ contributions. This complicates measurement of improvement in the interpersonal sphere. Second, emotional and interpersonal change is non-linear; distress often increases before the problem begins to resolve. In a role dispute that has reached an impasse, the patient may initially feel more distressed as she brings up long-suppressed feelings. In a brief (12–16) week acute therapy, in which many patients improve rapidly (Kelly, Cyranowski, & Frank, 2007), the window for detecting mediation effects is narrow.

Another approach to identifying active ingredients for understanding mechanisms is to dismantle therapeutic components. Perhaps exemplary was Jacobson’s classic study comparing cognitive behavior therapy for depression to its behavioral component alone (Jacobson et al., 1996). No comparable research has attempted to dismantle IPT and some have suggested IPT is too coherent a treatment to dissect into viable parts (Murphy et al., 2009). This is a testable hypothesis, however, and the approach may merit consideration in future IPT research.

The search for mediators of change is daunting. Negative findings have frustrated many researchers seeking to identify cognitive change mechanisms in depression, for example (Kazdin, 2007). Similar frustrations have beset other approaches, such as brief dynamic therapy (Grenyer & Luborsky, 1996). Nonetheless, identifying mediators may lead to refinements and improvements in IPT and enhance its application in a range of clinical populations. Thus the potential rewards of better understanding this already well-studied treatment outweigh the attendant difficulties.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Golan Shahar, Ph.D. and Gary M. Diamond, Ph.D. for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this report.

Footnotes

We use the term psychiatric rather than psychological disorder because IPT’s integrative theory incorporates the medical model of diagnosis and utilizes psychiatric nosology. No implication is intended of primacy of the contributions of one mental health discipline over another.

Given limited space for background on relational theory, we highlight two pivotal figures, Harry S. Sullivan and John Bowlby, and overlook many key figures of interpersonal psychoanalytic and object relational streams. The reader may seek a comprehensive review from, e.g., Greenberg and Mitchell (1983).

While it is important to consider methodological limitations inherent in research on stress and social support as causal factors in psychopathology (e.g., Hammen 2005; Paykel et al., 1969), discussion of these is beyond the scope of the current report.

Additional references, which could not be included due to page limitations, are included in the Appendix

References4

- Abraham K. Notes on the psycho-analytical investigation and treatment of manic-depressive insanity and allied conditions. In: Jones E, editor. Selected Papers of Karl Abraham. London: Hogarth; 1911/1927. pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MS. Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist. 1979;34(10):932–937. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.34.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden LE, Taylor CT. Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(7):857–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anchin JC, Kiesler DJ. Handbook of interpersonal psychotherapy. Vol. 1981. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton YA, Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Weissman MM. Religious attendance and social adjustment as protective against depression: A 10-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.037. Available online 6 September 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. London: Oxford; 2004. Retrieved from http://web.comhem.se/mentalize/mbt_training_jan_06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Sandeen EE, O’Leary KD. Depression in Marriage: A Model for Etiology and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Hersen M, Himmelhoch J. Social skills training compared with pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of unipolar depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1981;138(12):1562–1567. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.12.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bion WR. Attention and Interpretation. New York: Jason Aronson; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Hughes D, George LK. Stressful life events and the onset of a generalized anxiety syndrome. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144(9):1178–1183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleiberg KL, Markowitz JC. A Pilot Study of Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):181–183. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling EA. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(5):808–818. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(6):953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonime W. The psychodynamics of neurotic depression. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry. 1976;4(3):301–326. doi: 10.1521/jaap.1.1976.4.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. London: Hogarth; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol. 2. London: Penguin Books; 1973. Separation. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. I. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1977;130(3):201–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.130.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Bifulco A, Harris T, Bridge L. Life stress, chronic subclinical symptoms, and vulnerability to clinical depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1986;11(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. Oxon, UK: Taylor & Francis; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Brugha T, Stansfeld S, Freeman H. Social support, environment, and psychiatric disorder. In: Freeman HL, Stansfeld SA, editors. The Impact of the Environment on Psychiatric Disorder. Oxon, UK: Routledge; 2008. pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Butler SF, Strupp HH. Specific and nonspecific factors in psychotherapy: A problematic paradigm for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy. 1986;23(1):30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social Isolation and Health, with an Emphasis on Underlying Mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3):S39–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, Kowalewski RB, Berntson GG. Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(3):407–417. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira K, Miller MD, Frank E, Houck PR, Morse JQ, Dew MA, Reynolds CF., III A controlled evaluation of monthly maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy in late-life depression with varying levels of cognitive function. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23(11):1110–1113. doi: 10.1002/gps.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]