Abstract

Although the majority of studies on community noise levels and children's physiological stress responses are positive, effect sizes vary considerably, and some studies do not confirm these effects. Employing a contextual perspective congruent with soundscapes, a carefully constructed sample of children (N = 115, M = 10.1 yr) living in households in relatively high (>60 dBA) or low (<50 dBA) noise areas created by proximity to major traffic arterials in Austria was reanalyzed. Several personal and environmental factors known to affect resting cardiovascular parameters measured under well-controlled, clinical conditions were incorporated into the analyses. Children with premature births and elevated chronic stress (i.e., overnight cortisol) were more susceptible to adverse blood pressure responses to road traffic noise. Residence in a multi-dwelling unit as well as standardized assessments of perceived quietness of the area did not modify the traffic noise impacts but each had its own, independent effect on resting blood pressure. A primary air pollutant associated with traffic volume (NO2) had no influence on any of these results. The scope of environmental noise assessment and management would benefit from incorporation of a more contextualized approach as suggested by the soundscape perspective.

I. INTRODUCTION

Empirical research on noise impacts has focused, as it should, on the critical question of whether certain intensities of sound exposure can harm or threaten human health and well being. This main effect or direct effects model has a weakness, however. Human reactions to physical environmental conditions occur within an ecological context that shapes their responses. One key element of this contextualized perspective is that individual and social factors can alter the direct noise response function. To put it differently, sound intensity effects have the potential to differ or be moderated (i.e., statistical interaction) by other variables. The current study is a reanalysis of a relationship between transportation noise and blood pressure (BP) in schoolchildren published in 2001 (Evans et al., 2001). The reanalysis was conducted within the EU-funded 7th Framework project ENNAH with a special focus on effect modification (Lercher et al., 2011). Recent papers and reviews about the relationship between transportation noise and blood pressure in children continue to draw a somewhat inconsistent picture (Babisch et al., 2009; Babisch, 2011; Belojevic et al., 2008; van Kempen et al., 2006; Lepore et al., 2010; Paunović et al., 2011). Overall a positive association between noise exposure and children's blood pressure can be observed—although the effect is small and primarily seen for systolic blood pressure (Paunović et al., 2011). Methodological improvements such as repeated measures of blood pressure and better control of confounding variables (e.g., selection bias) remain as challenging issues. We have suggested (Evans and Lepore, 1997; Lercher et al., 2002; Lercher, 1996, 2007) that there is also a major conceptual weakness in most studies of environmental quality and human responses. Important individual and psychosocial factors are capable of modifying the impacts of environmental conditions such as noise. While the largest sources of variability remain age, gender, and bodily fat composition, the roles of ethnicity and socio-economic status are not yet fully clear (Paunović et al., 2011). Other environmental and life style factors, like home design, density, ambient air pollution, or physical activity and nutrition are also important candidates (Evans, 2003; Paunović et al., 2011). Susceptibility factors such as sensitivity to noise, degree of annoyance are rarely included in models of human health in addition to the physical indicator of noise exposure.

Furthermore, given that noise can act as a stressor and that exposure to multiple stressors can alter the health and behavioral impacts of singular environmental insults (DeFur et al., 2007; Evans and Marcynyszyn, 2004), another important issue to examine is the potential cumulative effect of these factors on indicators of chronic stress (e.g., cortisol).

Some of these potentially salient ecological contextual factors could be addressed in the present reanalysis. Thus, we explored herein the role of perceived quietness, perinatal variables (e.g., birth weight, preterm gestation), housing characteristics, and other environmental factors such as air pollution.

We also employed a more efficient research design strategy by stratified sampling at the high and low ends of the noise exposure spectrum from a larger representative survey.

II. METHODS

A. Subject selection and area description

A more detailed description was provided in two earlier reports (Evans et al., 2001; Lercher et al., 2002). In this smaller multi-method study (“trailer study”) subjects were selected from a larger representative sample of children from 26 local schools (N = 1280), mean age = 9.4 yr, response = 79.5%). Children, their mothers, and their teachers were informed that this was a study of traffic, environment, and health required by law to supplement an Environmental Health Impact Assessment. The survey area (about 45 km long) is an alpine valley and consists of small towns and villages with a mix of industrial, small business, and agricultural activities. Written informed consent was obtained from all children's parents after permission for this investigation was given by both the regional and each local school board.

Through a GIS-link a two-step stratified sampling was conducted.1 In the first step, children were sampled from the extremes of the noise exposure distribution (<50 dBA, Ldn vs >60 dBA, Ldn). In the second step, children were randomly selected and assigned to the low or high noise group by the educational status of their mothers. Participation rates in the trailer study was lower (64%) since parents were required to bring children to the mobile trailer and the overall procedure (tests and questionnaires) took up to an hour. However, the trailer sample did not differ significantly on various social, lifestyle, and biological factors from the larger one (Lercher et al., 2002).

B. Procedures

1. Questionnaire information

Socio-demographic data as well as biological risk information were collected from each child's mother in order to assess standard risk factors and to check for possible statistical interactions. Prenatal and perinatal data were assessed from doctor's entries in the “mother-child-passports”—every pregnant mother receives in Austria. Low birth weight (LBW) was defined as less than 2500 g and preterm birth as less than 37 weeks of gestation. Other biological variables recorded were maternal age, parity, and birth order. Further biological, social, and environmental data were collected with a self-administered, standardized questionnaire from the mother and from the children. Mother's education was scaled along a five point continuum from basic education (9 years of school) through university graduation (primary school, apprenticeship, technical/commercial college, A-level, university degree). In addition, density (room/person), house type (1 = single family detached, 2 = row house, 3 = multiple dwelling units), duration of residence (years), and months of breast feeding, were recorded.

By means of several in-class-administered questionnaire modules (under standardized guidance of two trained supervisors), we gathered further data from the children. The perception of the environment was assessed with a slightly adapted version (19 items) of the “environmental list” used in the Munich aircraft study on children (Meis, 1998). Various qualities of the living environment were assessed by a four-graded response scale “completely disagree—disagree—agree—completely agree” with a repeated question layout: “In my living area,” “The noise of the cars disturbs me,” “The noise of the trains disturbs me,” “The area is quiet,” etc. These three items were used as the four-graded response in the analysis of annoyance and perceived quietness of the area.

A 22 item scale, Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), was formed from two sub-scales of the KINDL (Bullinger et al., 1994), a validated index of children's quality of life, and four items on a sleep disturbance scale (Cronbach's α = 0.87) to create an overall assessment of children's health related quality of life.

2. Physiologic stress indicators

Cortisol is a frequently used biomarker to compare physiological stress between individuals. Cortisol and its potentially more sensitive metabolite 20a-dihydrocortisol in urine were used as indicators of chronic stress (Evans et al., 2001). Overnight urine (8-h) was collected with the assistance of the child's mother. The total volume was measured and four small sub-samples were randomly extracted. The four sub-samples were immediately frozen and stored at 70 °C until assayed. Free cortisol and 20a-dihydrocortisol were assayed with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (Schöneshöfer et al., 1985; Schöneshöfer et al., 1986). The creatinine-adjusted values were used in the statistical analysis to control for urinary flow rate.

C. Exposure assessment

In this study noise exposure (Leq) was assessed first by modeling (Soundplan®) the three major sources (highway, rail, local main road) according to Austrian guidelines (ÖAL Nr 28+30, ÖNORM S 5011). The dichotomous sampling for the trailer study was based on this information. Afterward, a calibration study (31 measuring points) was conducted (day and night measurements) and linear corrections were applied to the modeled data when the difference to the measured data exceeded 2 dB. Based on both data sources, approximate day-night levels (dB, A, Ldn) were calculated for each child's home to enable comparison with available dose-response data. This calibrated noise exposure information (combined levels from all sources) was used in all the dose-response analyses. Because of a correction after submission of the first publication on this sample (Evans et al., 2001), it was necessary to assign two children from the “high” noise sample to the “low” noise sample. Note that the change in assignment did not influence the main result. The noise range in the trailer study encompassed 31 to 72 dBA, Ldn (95% within: 34–50 dBA, Ldn in the low exposure group; 52–71 dBA, Ldn in the high exposure group).2

D. Outcome assessment

Resting blood pressure was measured by two trained investigators while the child was seated quietly in upright position. The children were tested individually in a climate controlled and sound attenuated (≤35 dBA) mobile trailer. After an initial practice reading to acclimate the child to the apparatus, two blood-pressure readings were taken with a calibrated sphygmomanometer (Bosch, Sysditon model) and appropriate cuff-sizes over a 6-min period. The average of the two readings was used in the analysis.

E. Statistical procedures

Exposure and survey data were linked through a Geographical information system and statistical analysis was conducted with F Harrell's HMISC-, and RMS-libraries (Harrell, 2011a,b). Epicalc was used to examine dichotomous variables for Table I by the Pearson χ2 test; numeric type data were subjected to the two-sample t-test unless residuals were not normally distributed or the variance of subgroups were not normally distributed (p = 0.01). In these cases medians and inter-quartile ranges are presented and the p-values of Wilcoxon Rank Sum test are reported (Chongsuvivatwong, 2011).

TABLE I.

Sample information about most important variables. a

| Categorical variables | <50 dBA, Ldn, n (%) | ≥60 dBA, Ldn, n (%) | Total, n (%) | χ2-test, p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.892 | |||

| male | 33 (55.9) | 33 (58.9) | 66 (57.4) | |

| female | 26 (44.1) | 23 (41.1) | 49 (42.6) | |

| 59(100.0) | 56(100.0) | 115(100.0) | ||

| Education | 0.835 | |||

| Lower < 12 years | 31 (53.4) | 32 (57.1) | 63 (55.3) | |

| Higher ≥ 12 years | 27 (46.6) | 24 (42.9) | 51 (44.7) | |

| Duration of gestation | 0.531 | |||

| < 37 weeks | 8 (13.6) | 11 (19.6) | 19 (16.5) | |

| ≥ 37 weeks | 51 (86.4) | 45 (80.4) | 96 (83.5) | |

| Family history of hypertension | 0.046 | |||

| yes | 4 (6.8) | 12 (21.4) | 16 (13.9) | |

| no | 55 (93.2) | 44 (78.6) | 99 (86.1) | |

| Housing type | 0.924 | |||

| Single/double home | 30 (50.8) | 28 (50.0) | 58 (50.4) | |

| Appartment home | 29 (49.2) | 28 (50.0) | 57 (49.6) | |

| Quiet area | 0.145 | |||

| Do not agree | 13 (22.0) | 8 (14.3) | 21 (18.3) | |

| Less agree | 27 (45.8) | 20 (35.7) | 47 (40.9) | |

| Agree | 13 (22.0) | 14 (25.0) | 27 (23.5) | |

| Fully agree | 6 (10.2) | 14 (25.0) | 20 (17.4) | |

| Annoyance rail | < 0.001 | |||

| Do not agree | 54 (91.5) | 29 (51.8) | 83 (72.2) | |

| Less agree | 3 (5.1) | 9 (16.1) | 12 (10.4) | |

| Agree | 1 (1.7) | 7 (12.5) | 8 (7.0) | |

| Fully agree | 1 (1.7) | 11 (19.6) | 12 (10.4) | |

| Annoyance road | 0.491 | |||

| Do not agree | 22 (37.3) | 18 (32.1) | 40 (34.8) | |

| Less agree | 17 (28.8) | 12 (21.4) | 29 (25.2) | |

| Agree | 12 (20.3) | 13 (23.2) | 25 (21.7) | |

| Fully agree | 8 (13.6) | 13 (23.2) | 21 (18.3) | |

| Continuous variables | < 50 dBA, Ldn | ≥ 60 dBA, Ldn | Total | t-test/ranksum test |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 0.154 | |||

| mean(SD) | 115.3 (7.1) | 117.4 (8.3) | 116.4 (7.5) | |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 0.949 | |||

| mean(SD) | 72.8 (7.1) | 72.9 (7.6) | 72.9 (7.5) | |

| Birth weight (g) | 0.591 | |||

| mean(SD) | 3304.7 (498.5) | 3247.9 (627.7) | 3270.1 (554.3) | |

| 20α-Dihydrocortisol, μg/8 h | 0.032 | |||

| median(IQR) | 7 (5.0,9.6) | 8.7 (5.9,12) | 7.7 (5.5,11.5) | |

| BMI | 0.376 | |||

| median(IQR) | 16.8 (15.4,18.5) | 17.1 (15.8,18.9) | 17 (15.5,18.7) | |

| HRQoL scale | 0.022 | |||

| median(IQR) | 96 (89.0,104.5) | 91 (82.8,99.2) | 92 (87,102.5) | |

| NO2-levels μg/m3 | < 0.001 | |||

| median(IQR) | 29.9 (27.7,31.3) | 36.7 (34.6,39.1) | 32.1 (29.1,36.6) | |

Degrees of freedom vary because of missing data. Because of exposure correction at some homes 2 from the 115 children in the original analysis were reassigned to the low noise sample (N = 57 vs 58 previously).

For modeling exposure-effect relationships, multiple logistic regression techniques and splines were applied to account for non-linearity in selected predictors (Harrell, 2001). Approximate 95% confidence intervals were estimated using smoothing spline routines with three knots and exposure-effect plots generated with the RMS-library (Harrell, 2011b). On the basis of prior knowledge, we entered first a minimum set of standard risk factors [sex, body mass index (BMI), maternal education, family history of hypertension, duration of gestation, birth weight], individual response factors (HRQoL scale, cortisol), environmental factors (density, house type, NO2), environmental perception (annoyance, quietness) and noise exposure. Selected testing of potentially effect modifying factors (noise*gestation, noise*cortisol, noise*NO2, noise*HRQoL) followed. Very high correlated factors were evaluated individually and in combination. Birth weight, HRQoL, NO2, density, annoyance were removed after validation by bootstrapping (Harrell, 2011b) and evaluation against multiple discrimination criteria [AIC, R2, model χ2, Somers' Dxy, Spearman's ρ, γ, τ-a, C (area under ROC curve)]. Eventually, the final model was penalized to account for the potential risk of overfitting in relatively small data sets where the number of predictors is large relative to the number of events studied (Harrell, 2001; Janssen et al., 2012; Steyerberg et al., 2004). The penalizing procedures yields more conservative but more robust estimates of model parameters.

III. RESULTS

A. Sample and variable description

Table I shows that the stratified sampling resulted in no significant differences in the main background variables of the two samples with respect to education, sex, BMI, height, family history of hypertension, or housing. Although the two samples differed acoustically by 10 dBA, perceived noise levels were not statistically different between the two samples. Among the reported annoyances, only annoyance due to rail differed significantly but not due to road noise. The stronger annoyance due to rail noise for the home setting agrees with the experimental results when children were exposed to recordings in the trailer (not shown). Significant differences between the two noise samples were observed only with overnight 20α-dihydocortisol-levels and the HRQoL scale. Near significant results were observed with shorter gestation and systolic blood pressure, while no differences were uncovered for diastolic blood pressure.

B. Blood pressure: Main effects

Only the results from systolic blood pressure are shown here. The diastolic blood pressure model did perform completely different from the systolic model with BMI as the dominant significant and single predictive factor: 4.99 (2.94–7.04) mm Hg.

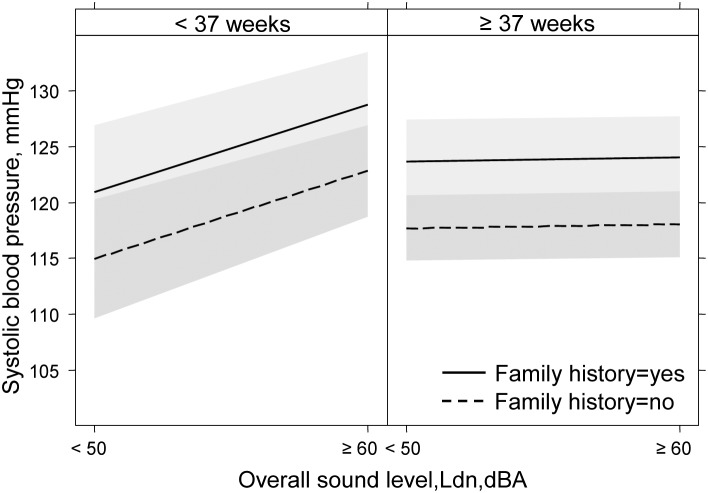

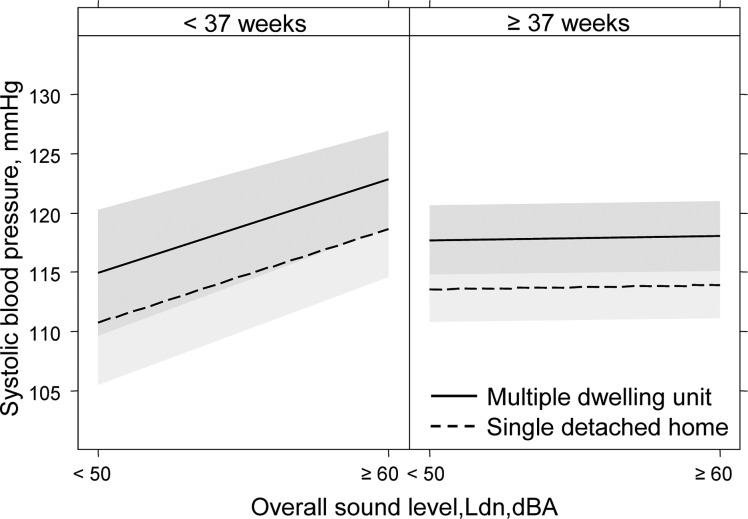

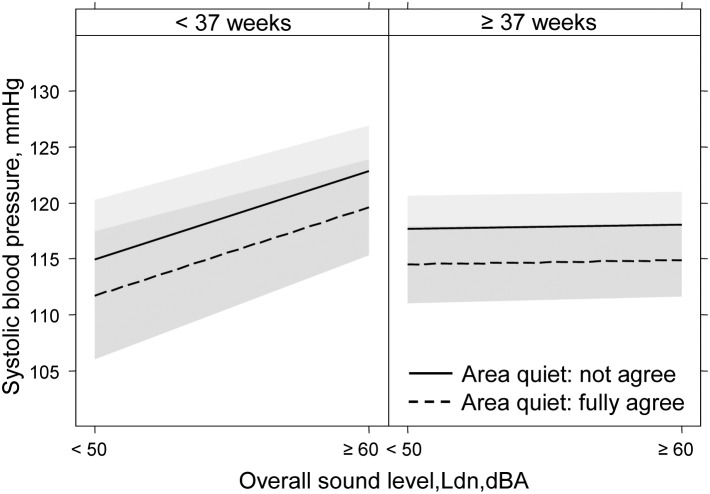

In the presence of two interactions (see Sec. III C), only those main effects on systolic blood pressure are reported here that are not affected by these processes. Because of sampling on one school grade, age was not a relevant predictor. The five strongest contributors (expressed as inter-quartile blood pressure effects) were family history of hypertension: 6.03 (3.24, 8.82) mm Hg; living in a multiple apartment, compared to a single detached home: 4.16 (1.98, 6.35) mm Hg; BMI (interquartile difference): 2.76 (1.06, 4.47) mm Hg; rating the living area as quiet: −1.66 (−2.83, −0.49) mm Hg; male sex: 3.08 (0.86, 5.30) mm Hg; maternal education < 12 yr: 2.68 (0.50, 4.86) mm Hg. The variance explained by the penalized model remained high (adjusted R2 = 0.42) compared with other studies.

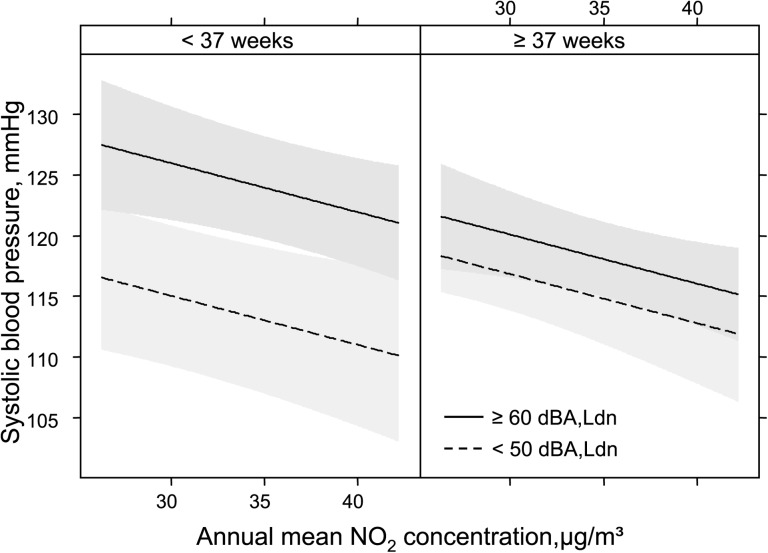

A significant effect was observed for annual NO2-levels—but not in the hypothesized direction (negative coefficient: see Fig. 4). Both annoyance indicators (road, rail) were not significant in the presence of the soundscape indicator “area is quiet.” The coefficient of the soundscape indicator remained unchanged also in the presence of both annoyance variables.

FIG. 4.

Systolic blood pressure model, adjusted for BMI, sex, education, family history, cortisol, house type, area quiet, sound*gestation, sound*cortisol.

C. Blood pressure: Effect modification

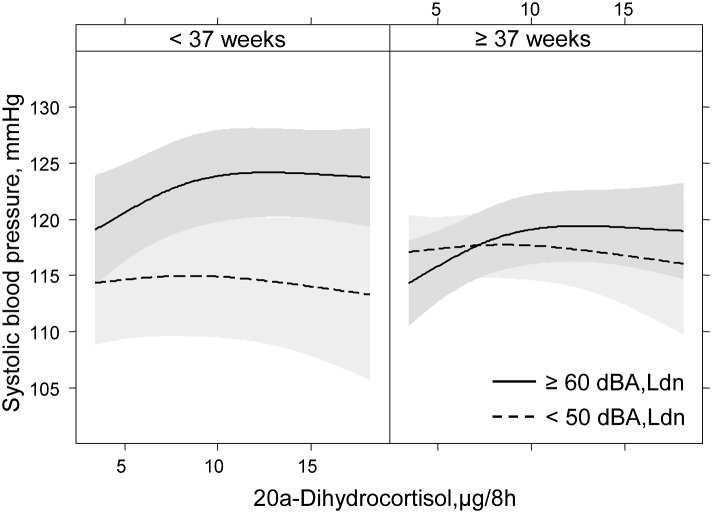

The adjusted and penalized regression model revealed two relevant interactions of noise exposure with duration of gestation (p = 0.0136) and overnight cortisol-excretion (p = 0.1018) in urine. In Figs. 1–4 the effect modification by gestation time is compared in the two noise samples with the most relevant other predictors. While the main effect size of the respective covariate changes, inspection of the slope reveals a constant difference between the lower and the higher exposed noise sample of about 7 mm Hg.

FIG. 1.

Systolic blood pressure model, adjusted for BMI, sex, house type, education, cortisol, area quiet, sound*gestation, sound*cortisol.

FIG. 2.

Systolic blood pressure model, adjusted for BMI, sex, education, cortisol, family history, area quiet, sound*gestation, sound*cortisol.

FIG. 3.

Systolic blood pressure model, adjusted for BMI, sex, family history, education, cortisol, house type, sound*gestation, sound*cortisol.

Figure 5 shows a non-linear effect modification between higher cortisol-excretion in urine and noise level but only among children born preterm. It is actually a three-way interaction and underestimated by our conservative two-way statistical assessment to avoid overfitting. The presence of non-linearity can also misrepresent the true effect by classical means (p-value) due to lower statistical power.

FIG. 5.

Systolic blood pressure model, adjusted for BMI, sex, family history, education, house type, area quiet, sound*gestation.

No interaction was found between noise and annual NO2 levels.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. The investigated interactions

Typical ambient levels of noise in communities along alpine major traffic arterials are associated with increases of systolic blood pressure in a representative population sample of elementary school children. This association is, however, only manifest in children who are preterm and/or show higher urinary excretion of cortisol metabolites. These findings could not be replicated with diastolic blood pressure where other predictors were dominant. None of the previous blood pressure studies in children reported or analyzed the interaction of noise with shorter gestation time. The result is in agreement with an earlier finding, where an effect modification between noise and preterm birth was observed on self-reported mental health in children (Lercher et al., 2002). In the RANCH study (van Kempen et al., 2006), premature children also exhibited higher blood pressure [2.76 (−0.26,5.78) mm Hg at home model number 2]. However, this result was only of borderline significance and no interaction was reported. These two findings were the prime rationale for the inclusion of preterm birth in our reanalysis.

The non-linear interaction between noise and the overnight urinary cortisol excretion is a new finding supporting the hypothesis that chronic noise exposure during the night may act as a moderator of systolic blood pressure. Other studies have shown night time cortisol increases in noise exposed school children (Evans et al., 2001; Ising et al., 2004; Ising and Ising, 2002)—but these prior studies did not investigate possible linkages to blood pressure. The Munich longitudinal noise study also found no relations between chronic aircraft noise exposure and elevated overnight cortisol, although significant effects were found for adrenaline and noradrenaline (Evans et al., 1998; Evans et al., 1995). A Swedish study on the effects of classroom noise on children's blood pressure did not find a correlation between salivary cortisol and blood pressure (Wålinder et al., 2007). We have found a relationship with the urinary metabolite 20α-Dihydrocortisol in this study but not with free cortisol. This may reflect greater sensitivity of the cortisol metabolite to environmental conditions compared to overall, free cortisol levels.

Urinary cortisol has been linked with cardiovascular risk, and longitudinal studies have shown evidence that high cortisol levels predict cardiovascular death among persons both with and without pre-existing cardiovascular disease (Vogelzangs et al., 2010). Another study found flatter slopes in cortisol decline across the day to be associated with the increased mortality risk (Kumari et al., 2011). One possible explanation for our findings herein could be that premature children respond with greater hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) activation to noise and possibly various stressors more generally (Brummelte et al., 2011). This interaction also fits well with the fetal programming hypothesis (Barker, 1996; van Dijk et al., 2010; Gustafsson et al., 2010). Since stress can result in prenatal activation of the maternal or fetal HPA axis it is increasingly recognized as an important cause of late preterm birth (Gravett et al., 2010) and as suggested by the fetal programming hypothesis greater reactivity to environmental insults throughout life (Miller et al., 2011).

No effect modification was observed between noise and air pollution (NO2). This is in accordance with the current literature in adult studies (Beelen et al., 2009; Huss et al., 2010; De Kluizenaar et al., 2007; Lercher et al., 2008; Selander et al., 2009; Lekaviciute et al., 2012). Only one child study investigated an interaction between noise and air pollution with regard to bronchitis and found a positive association (Ising et al., 2004). Our study is the first to investigate this type of interaction regarding a cardiovascular outcome. There was also no significant main effect—even when noise exposure was removed from the model. This adds credence to the result, since—as expected—the correlation between noise exposure and NO2-levels was high (r = 0.75).

B. The main effects

Family history, BMI, and sex were the most important standard variables in the adjusted model. For the first time a soundscape indicator (“quiet area”) showed a stable, independent and inverse association with an objective health measure such as systolic blood pressure. Hitherto, effects of positively rated soundscapes have only been associated with lower annoyance, pleasantness, and wellbeing or with better perceived health in quality of life in surveys (Gidlöf-Gunnarsson and Öhrström, 2010; Öhrström et al., 2006) soundscape studies or in short-term experiments (Hume and Ahtamad, 2011). Although the prior results on soundscape quality and subjective indicators of health are important, the present findings of a link between soundscape and a physiological measure of clinical relevance, resting blood pressure, provide additional evidence to the view that soundscapes extend our understanding of noise and human responses beyond the pure assessment of sound intensity exposure.

It is important to note that the coefficient of the “soundscape” indicator did not change in the presence of both annoyance indicators (road, rail) in the adjusted regression model.

This means that both overestimations and underestimations may occur by using the annoyance response as sole indicator of potentially adverse health effects in children.

Another relevant environmental factor—the type of home (apartment vs single detached home)—turned out to be a significant and stable predictor in addition to noise level and subjective perception. In terms of the Wald statistic, it was the second most important contributor in the systolic blood pressure model after family history of hypertension. Although the type of home is known to affect the degree of noise annoyance (Björk et al., 2006; Fields, 1993; Sato et al., 2002) and the risk of hypertension in adults (Barregard et al., 2009; Bluhm et al., 2007), the results are conflicting. In the only noise children study hitherto reported, children living in apartment homes showed greater annoyance (Lercher et al., 2000). In the same study higher density (person/room) was also associated with higher annoyance due to road noise—but not due to rail noise. The true underlying reason for house type as an important predictor is far from being fully understood (Braubach et al., 2011)—especially when educational background has been taken into account in the present analysis. Density was not a significant predictor after the final model validation.

Another possibility could be that the combined effects of noise and other risk factors associated with multiple family compared to single detached residence may accumulate and at a certain inflection point create adverse stress effects (deFur et al., 2007). Evans and Marcynyszyn (2004), for example, showed that low-income children exposed to elevated residential housing risks had significant higher levels of overnight stress hormones, including cortisol.

Other amenities and qualities of the environment near the home such as gardens, space for playing, “I like to live here,” etc. may be related to the more favorable blood pressure outcome of children living in single detached homes (Lercher et al., 2000). Another relevant environmental factor could be the insulation of the home against noise. In the Sydney airport noise study, a significant association between living in insulated homes and lower systolic blood pressure was reported in children (Morrell et al., 1998).

Because of the alpine climate, the insulation standard of homes is high, and we do not consider this aspect of relevance in our study. However, we had no control over children's operation of windows.

Annual NO2-levels revealed a significant inverse effect in the presence of noise in the model. As the direction of this effect is counter to prevailing models, we suggest this association is likely an artifact due to high collinearity with noise. The noise effect remained unchanged in the presence of NO2-levels.

Among the personal susceptibility indicators neither noise sensitivity nor quality of life were significant predictors in the final model.

C. Strength and weaknesses

The two-stage-stratified sampling from a larger data base of children resulted in a quite evenly distribution of variables in a smaller data set without losing power and enriched by additional information. By leaving a 10 dBA difference between the high and the low noise sample, the exposure contrast was increased in comparison to community noise studies. Use of sample subgroups stratified by noise exposure extremes in conjunction with larger epidemiological surveys of random community samples offers promise worthy of further consideration by noise and health researchers (Lercher et al., 2002; Lercher et al., 2011). The additional information of potentially interacting variables allowed us to test various hypotheses recently suggested in a review (Paunović et al., 2011). Furthermore, through rigorous statistical treatment (bootstrapping and penalization), we avoided overestimation of predictors which may occur in small samples. The noise exposure assessment was of equal high quality for both sources and the overall noise level at home was used in the analysis, since the children stay only about 5–6 h/d in school or on transit. The noise modeling was corrected through local day and night measurements. Multiple blood pressure readings were obtained in a highly controlled, quiet environment by only two carefully trained observers. Therefore, it is not surprising that the standard deviations of both systolic and diastolic readings were smaller than in the large RANCH study (systolic: 7.5 vs 10.4; diastolic: 7.5. vs 8.3) (van Kempen et al., 2006)—providing more power in hypothesis testing. The blood pressure readings in our study were higher than in other samples (Paunović et al., 2011). This finding of higher blood pressure readings was, however, already observed in an earlier study conducted in the same area with the same equipment (Lercher, 1992).

Among the limitations of this study are the cross-sectional research design, which prohibits causal interpretation, and the small sample, which precludes the simultaneous assessment of a larger set of contextual factors that ideally might represent a better picture of the ecological context of children's soundscapes. Since some children may have been shielded from noise in their sleeping room, a certain degree of noise exposure misclassification cannot be excluded. Our study did not include nutritional indicators or physical activities which are robust predictors for blood pressure. BMI may, however, be a reasonable surrogate.

D. Interpretation and conclusion

The effect size on blood pressure in interaction with noise is larger than reported in other studies (van Kempen et al., 2006; Paunović et al., 2011). The observed effect of environmental variables like type of dwelling or perceived quietness needs confirmation from larger studies. The meaning of these environmental variables can vary substantially in an international context. The judgment of blood pressure elevations in childhood is heterogeneous. While epidemiologists find strong evidence for “tracking” of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood (Bao et al., 1995; Chen and Wang, 2008) clinicians regard blood pressure elevations of this size as temporary psycho-physiologic adaptation to a demanding environment. While the clinical interpretation may be true at individual level and early clinical treatment is not indicated—within a public health perspective, the observed effect size may be relevant in the long term, especially when you look at it from a cumulative risk perspective (DeFur et al., 2007; Evans and Marcynyszyn, 2004).

We cannot distinguish in our study whether the noise effect is due to day or night exposure since the equally high nightly noise load (due to freight rail) is a distinct feature of the exposure in this area. On the other hand, there are good reasons to believe the high noise exposure during night is the crucial component. Further support for this hypothesis is provided by the significant interaction of noise and overnight cortisol. Thus, the observed effect might also be attributed to disturbed sleep of these children (Maschke and Hecht, 2004).

This study shows that specific research is needed to better assess the larger environmental context in which noise occurs. We have to learn when a “soundscape” turns into a “noisescape” (Brown, 2010; De Coensel et al., 2009) and potentially exerts negative effects on blood pressure and other developmental mechanisms salient for health in children. We also need to investigate in further detail the enviroscape and the psychscape (Job and Hatfield, 2001) in both soundscape and annoyance studies (Lercher and Schulte-Fortkamp, 2003). Improving the environmental quality of the home and near-home environment through targeted planning and design is a promising approach to support health (Evans, 2003; Öhrström et al., 2006).

In accordance with the WHO-perspective, this requires conceptualizing the residential environment as a health resource that promotes sustainable physical, mental, and social health and well-being (Braubach et al., 2011; Lercher, 2007). Incorporating the residential environment into health promotion requires widening the scope of environmental noise management to soundscape analysis and design (Berglund and Nilsson, 2006; Brambilla and Maffei, 2010; Brown, 2010; Kang, 2011; Schulte-Fortkamp and Fiebig, 2006; Truax and Barrett, 2011).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the many children, families, and teachers who participated in this research project. This research was mainly supported by the Austrian Ministry of Science and Transportation. Further support came from the Austrian-US Fulbright Commission, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, No. 1F33 HD08473-01. Funding for this reanalysis was provided during “ENNAH” within the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme ([FP7/2007-2013]) under grant agreement no. 226442.

Footnotes

See https://www.i-med.ac.at/sozialmedizin/en/projects/jasa_07-2013/ for an outline of stratified sampling.

See https://www.i-med.ac.at/sozialmedizin/en/projects/jasa_07-2013/ for sound exposure distribution in low and high exposure sample.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babisch, W. (2011). “ Cardiovascular effects of noise,” in Encyclopedia of Environmental Health, edited by Nriagu J. O. (Elsevier, Burlington, MA: ), pp. 532–542 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babisch, W., Neuhauser, H., Thamm, M., and Seiwert, M. (2009). “ Blood pressure of 8–14 year old children in relation to traffic noise at home–results of the German Environmental Survey for Children (GerES IV),” Sci. Total. Environ. 407, 5839–5843 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao, W., Threefoot, S. A. , Srinivasan, S. R. , and Berenson, G. S. (1995). “ Essential hypertension predicted by tracking of elevated blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: The Bogalusa heart study,” Am. J. Hypertens. 8, 657–665 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00116-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker, D. J. (1996). “ The fetal origins of hypertension,” J. Hypertens. Suppl. 14, S117–120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barregard, L., Bonde, E., and Öhrström, E. (2009). “ Risk of hypertension from exposure to road traffic noise in a population-based sample,” Occup. Environ. Med. 66, 410–415 10.1136/oem.2008.042804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beelen, R., Hoek, G., Houthuijs, D., van den Brandt, P. A. , Goldbohm, R. A. , Fischer, P., Schouten, L. J. , Armstrong B., and Brunekreef B. (2009). “ The joint association of air pollution and noise from road traffic with cardiovascular mortality in a cohort study,” Occup. Environ. Med. 66, 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belojevic, G., Jakovljevic, B., Stojanov, V., Paunovic, K., and Ilic, J. (2008). “ Urban road-traffic noise and blood pressure and heart rate in preschool children,” Environ. Int. 34, 226–231 10.1016/j.envint.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berglund, B., and Nilsson, M. E. (2006). “ On a tool for measuring soundscape quality in urban residential areas,” Acta Acust. Acust. 92, 938–944 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björk, J., Ardö, J., Stroh, E., Lövkvist, H., Östergren, P.-O., and Albin, M. (2006). “ Road traffic noise in southern Sweden and its relation to annoyance, disturbance of daily activities and health,” Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 32, 392–401 10.5271/sjweh.1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bluhm, G., Berglind, N., Nordling, E., and Rosenlund, M. (2007). “ Road traffic noise and hypertension,” Occup. Environ. Med. 64, 122–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brambilla, G., and Maffei, L. (2010). “ Perspective of the soundscape approach as a tool for urban space design,” Noise Control Eng. J. 58, 532–539 10.3397/1.3484180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braubach, M., Jacobs, D. E. , and Ormandy, D. (2011). Environmental burdens of disease associated with inadequate housing, summary report (WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen), pp. 1–16

- 13.Brown, A. L. (2010). “ Soundscapes and environmental noise management,” Noise Control Eng. J. 58, 493–500 10.3397/1.3484178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brummelte, S., Grunau, R. E. , Zaidman-Zait, A., Weinberg, J., Nordstokke, D., and Cepeda, I. L. (2011). “ Cortisol levels in relation to maternal interaction and child internalizing behavior in preterm and full-term children at 18 months corrected age,” Dev. Psychobiol. 53, 184–195 10.1002/dev.20511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bullinger, M., Von Mackensen, S., and Kirchberger, I. (1994). “ KINDL - ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität von Kindern” (“KINDL - a questionnaire for the assessment of health related quality of life in children”), J. Health Psychol. 2, 64–77 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, X., and Wang, Y. (2008). “ Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis,” Circulation 117, 3171–3180 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chongsuvivatwong, V. (2011). “R-epicalc library,” http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/epicalc/index.html (Last viewed April 8, 2012).

- 18.De Coensel, B., Botteldooren, D., De Muer, T., Berglund, B., Nilsson, M. E. , and Lercher, P. (2009). “ A model for the perception of environmental sound based on notice-events,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 656–665 10.1121/1.3158601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeFur, P. L. , Evans, G. W. , Cohen Hubal, E. A. , Kyle, A. D. , Morello-Frosch, R. A. , and Williams, D. R. (2007). “ Vulnerability as a function of individual and group resources in cumulative risk assessment,” Environ. Health. Perspect. 115, 817–824 10.1289/ehp.9332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Kluizenaar, Y., Gansevoort T., Miedema H. M., and De Jong P. E. (2007). “ Road traffic noise and hypertension,” J. Occup. Environ. Med. 49, 484–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans, G. W. (2003). “ The built environment and mental health,” J. Urban. Health. 80, 536–555 10.1093/jurban/jtg063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans, G. W., Bullinger, M., and Hygge, S. (1998). “ Chronic noise exposure and physiological response: A prospective study of children living under environmental stress,” Psychol. Sci. 9(1 ), 75–77 10.1111/1467-9280.00014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evans, G. W., Hygge, S., and Bullinger, M. (1995). “ Chronic noise and psychological stress,” Psychol. Sci. 6(6 ), 333–338 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00522.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans, G. W. , and Lepore, S. J. (1997). “ Moderating and mediating processes in environment-behavior research,” in Advances in Environment, Behavior, and Design, edited by Moore G. T. and Marans R. W. (Plenum, New York: ), Vol. 4, pp. 255–285 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans, G. W. , Lercher, P., Meis, M., Ising, H., and Kofler, W. W. (2001). “ Community noise exposure and stress in children,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109, 1023–1027 10.1121/1.1340642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans, G. W. , and Marcynyszyn, L. A. (2004). “ Environmental justice, cumulative environmental risk, and health among low- and middle-income children in upstate New York,” Am. J. Public. Health. 94, 1942–1944 10.2105/AJPH.94.11.1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fields, J. M. (1993). “ Effect of personal and situational variables on noise annoyance in residential areas,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 93, 2753–2763 10.1121/1.405851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gidlöf-Gunnarsson, A., and Öhrström, E. (2010). “ Attractive ‘quiet’ courtyards: A potential modifier of urban residents' responses to road traffic noise?,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 7, 3359–3375 10.3390/ijerph7093359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gravett, M. G. , Rubens, C. E. , and Nunes, T. M. (2010). “ Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (2 of 7): Discovery science,” BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10(Suppl 1 ), S2. 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafsson, P. E. , Janlert, U., Theorell, T., and Hammarström, A. (2010). “ Is body size at birth related to circadian salivary cortisol levels in adulthood? Results from a longitudinal cohort study,” BMC Public Health 10, 346. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrell, F. (2001). Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis (Springer, New York), pp. 1–374 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrell, F. E. , Jr. (2011a). “ R-Hmisc library,” http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/index.html (Last viewed April 8, 2011).

- 31.Harrell, F. E. Jr. (2011b). “R-rms library,” http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html (Last viewed April 8, 2011).

- 32.Hume, K., and Ahtamad, M. (2011). “ Physiological responses to and subjective estimates of soundscape elements,” Appl. Acoustics 74, 275–281 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huss, A., Spoerri, A., Egger, M., and Röösli, M. (2010). “ Aircraft noise, air pollution, and mortality from myocardial infarction,” Epidemiology 21, 829–836 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f4e634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ising, H., and Ising, M. (2002). “ Chronic cortisol increases in the first half of the night caused by road traffic noise,” Noise Health 4, 13–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ising, H., Lange-Asschenfeldt, H., Moriske, H.-J., Born, J., and Eilts, M. (2004). “ Low frequency noise and stress: Bronchitis and cortisol in children exposed chronically to traffic noise and exhaust fumes,” Noise Health 6, 21–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janssen, K. J. M. , Siccama, I., Vergouwe, Y., Koffijberg, H., Debray, T. P. A. , Keijzer, M., Grobbee, D. E. , and Moons, K. G. (2012). “ Development and validation of clinical prediction models: Marginal differences between logistic regression, penalized maximum likelihood estimation, and genetic programming,” J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65, 404–412 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Job, R. F. S. , and Hatfield, J. (2001). “ The impact of soundscape, enviroscape, and psychscape on reaction to noise: Implications for evaluation and regulation of noise effects,” Noise Control Eng. J. 49, 120. 10.3397/1.2839647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang, J. (2011). “ Noise management: Soundscape approach,” in Encyclopedia of Environmental Health (Elsevier, Burlington, MA: ), pp. 174–184 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumari, M., Shipley, M., Stafford, M., and Kivimaki, M. (2011). “ Association of diurnal patterns in salivary cortisol with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: Findings from the Whitehall II study,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 1478–1485 10.1210/jc.2010-2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lekaviciute, J., de Kluizenaar, Y., Laszlo, H., Hansell, A., Floud, S., Lercher, P., Babisch, W., and Kephalopolous S. (2012). “ Cardiovascular effects of the combined exposure to noise and outdoor air pollution: A review,” in Proceedings of Internoise 2012 (I-INCE, New York: ). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lepore, S. J. , Shejwal, B., Kim, B. H. , and Evans, G. W. (2010). “ Associations between chronic community noise exposure and blood pressure at rest and during acute noise and non-noise stressors among urban school children in India,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 7, 3457–3466 10.3390/ijerph7093457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lercher, P. (1992). “ Auswirkungen des Straßenverkehrs auf Lebensqualität und Gesundheit: Transitstudie - Sozialmedizinischer Teilbericht” (“Effects of road traffic on quality of life and health: Transit traffic study—Social medicine substudy report”) (Federal State Government Office, Innsbruck, Austria), p. 17

- 43.Lercher, P. (1996). “ Environmental noise and health: An integrated research perspective,” Environ. Int. 22, 117–129 10.1016/0160-4120(95)00109-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lercher, P. (2007). “ Environmental noise: A contextual public health perspective,” in Noise and its Effects, edited by Luxon D., Linda M., and Prasher E. (Wiley, London: ), pp. 345–377 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lercher, P., Botteldooren, D., Widmann, U., Uhrner, U., and Kammeringer, E. (2011). “ Cardiovascular effects of environmental noise: Research in Austria,” Noise Health 13, 234–250 10.4103/1463-1741.80160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lercher, P., Brauchle, G., and Kofler, W. (2000). “ The assessment of noise annoyance in schoolchildren and their mothers,” in Proceedings of Internoise 2000, edited by Cassereau D. (Société Française d'Acoustique, Nice, France: ), Vol. 4, pp. 2318–2322 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lercher, P., de Greve, B., Botteldooren, D., Dekoninck, L., Oettl, D., Uhrner, U., and Rüdisser, J. (2008), “ Health effects and major co-determinants associated with rail and road noise exposure along transalpine traffic corridors,” in Proceedings of ICBEN 2008 “Noise as a Public Health problem” [CD] (International Commission of the Biological Effects of Noise, Mashantucket, CT), pp. 322–332. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lercher, P., Evans, G. W. , Meis, M., and Kofler, W. W. (2002). “ Ambient neighbourhood noise and children's mental health,” Occup. Environ. Med. 59, 380–386 10.1136/oem.59.6.380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lercher, P., and Schulte-Fortkamp, B. (2003). “ The relevance of soundscape research for the assessment of annoyance at the community level,” Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Noise as a Public Health Problem [CD] (Foundation ICBEN, Rotterdam), pp. 225–231 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maschke, C., and Hecht, K. (2004). “ Stress hormones and sleep disturbances—Electrophysiological and hormonal aspects,” Noise Health 6, 49–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meis, M. (1998). Zur Wirkung von Lärm auf das Gedächtnis: Explizite und implizite Erinnerungsleistungen fluglärmexponierter Kinder im Rahmen einer medizinpsychologischen Längsschnittstudie (On the Effects of Noise on Memory: Explicit and Implicit Memory Performance of Children Exposed to Aircraft Noise in a Medical-Psychological Longitudinal Study) (Verlag Kovac, Hamburg, Germany), pp. 1–189 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller, G. E. , Chen, E., and Parker, K. J. (2011). “ Psychological stress in childhood and suceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving towards a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms,” Psychol. Bull. 137, 959–997 10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrell, S., Taylor, R., Carter, N. L. , Job, R. F. S. , and Peploe, P. (1998). “ Cross-sectional relationship between blood pressure of school children and aircraft noise,” in Noise Effects: 7th International Congress on Noise as a Public Health Problem, Noise Effects 98, edited by Job R. F. S. and Carter N. L. (Pty. Ltd., Sydney, Australia), Vol. 1, pp. 275–279 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Öhrström, E., Skanberg, A., Svensson, H., and Gidlof-Gunnarsson, A. (2006). “ Effects of road traffic noise and the benefit of access to quietness,” J. Sound. Vib. 295, 40–59 10.1016/j.jsv.2005.11.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paunović, K., Stansfeld, S., Clark, C., and Belojević, G. (2011). “ Epidemiological studies on noise and blood pressure in children: Observations and suggestions,” Environ. Int. 37, 1030–1041 10.1016/j.envint.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sato, T., Yano, T., Björkman, M., and Rylander, R. (2002). “ Comparison of community response to road traffic noise in Japan and Sweden—Part I: Outline of surveys and dose–response relationships,” J. Sound. Vib. 250, 161–167 10.1006/jsvi.2001.3892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schöneshöfer, M., Kage, A., Weber, B., Lenz, I., and Köttgen, E. (1985). “ Determination of urinary free cortisol by ‘on-line’ liquid chromatography,” Clin. Chem. 31, 564–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schöneshöfer, M., Weber, B., Oelkers, W., Nahoul, K., and Mantero, F. (1986). “ Measurement of urinary free 20 alpha-dihydrocortisol in biochemical diagnosis of chronic hypercorticoidism,” Clin. Chem. 32, 808–810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schulte-Fortkamp, B., and Fiebig, A. (2006). “ Soundscape analysis in a residential area: An evaluation of noise and people's mind,” Acta Acust. Acust. 92, 875–880 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Selander, J., Nilsson, M. E. , Bluhm, G., Rosenlund, M., Lindqvist, M., Nise, G., and Pershagen, G. (2009). “ Long-term exposure to road traffic noise and myocardial infarction,” Epidemiology 20, 272–279 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31819463bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steyerberg, E. W. , Borsboom, G. J. J. M. , van Houwelingen, H. C. , Eijkemans, M. J. C. , and Habbema, J. D. F. (2004). “ Validation and updating of predictive logistic regression models: A study on sample size and shrinkage,” Stat. Med. 23, 2567–2586 10.1002/sim.1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Truax, B., and Barrett, G. W. (2011). “ Soundscape in a context of acoustic and landscape ecology,” Landscape Ecol. 26, 1201–1207 10.1007/s10980-011-9644-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Dijk, A. E. , van Eijsden, M., Stronks, K., Gemke, R. J. B. J. , and Vrijkotte, T. G. M. (2010). “ Cardio-metabolic risk in 5-year-old children prenatally exposed to maternal psychosocial stress: The ABCD study,” BMC Public Health 10, 251. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Kempen, E., van Kamp, I., Fischer, P., Davies, H., Houthuijs, D., Stellato, R., Clark, C., and Stansfeld, S. (2006). “ Noise exposure and children's blood pressure and heart rate: The RANCH project,” Occup. Environ. Med. 63, 632–639 10.1136/oem.2006.026831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vogelzangs, N., Beekman, A. T. F. , Milaneschi, Y., Bandinelli, S., Ferrucci, L., and Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2010). “ Urinary cortisol and six-year risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 4959–4964 10.1210/jc.2010-0192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wålinder, R., Gunnarsson, K., Runeson, R., and Smedje, G. (2007). “ Physiological and psychological stress reactions in relation to classroom noise,” Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 33, 260–266 10.5271/sjweh.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]