Abstract

Many mutations in the skeletal-muscle sodium-channel gene SCN4A have been associated with myotonia and/or periodic paralysis, but so far all of these mutations are located in exons. We found a patient with myotonia caused by a deletion/insertion located in intron 21 of SCN4A, which is an AT-AC type II intron. This is a rare class of introns that, despite having AT-AC boundaries, are spliced by the major or U2-type spliceosome. The patient's skeletal muscle expressed aberrantly spliced SCN4A mRNA isoforms generated by activation of cryptic splice sites. In addition, genetic suppression experiments using an SCN4A minigene showed that the mutant 5′ splice site has impaired binding to the U1 and U6 snRNPs, which are the cognate factors for recognition of U2-type 5′ splice sites. One of the aberrantly spliced isoforms encodes a channel with a 35-amino-acid insertion in the cytoplasmic loop between domains III and IV of Nav1.4. The mutant channel exhibited a marked disruption of fast inactivation, and a simulation in silico showed that the channel defect is consistent with the patient's myotonic symptoms. This is the first report of a disease-associated mutation in an AT-AC type II intron, and also the first intronic mutation in a voltage-gated ion channel gene showing a gain-of-function defect.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, myotonia, splicing, gain-of-function, simulation, channelopathy

Introduction

Genetic defects in voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav) genes are responsible for several hereditary diseases [George AL, Jr., 2005]. Physiological studies of the mutant channels have revealed two types of functional defects, characterized by loss or reduction of conductivity (loss of function) or by altered gating (gain of function). Mutations in the skeletal-muscle sodium-channel gene SCN4A (MIM# 603967) are usually associated with myotonia and/or periodic paralysis and in a rare case with fatigable weakness (congenital myasthenia), and this type of disorder is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion [Cannon SC, 2006; Tsujino A et al., 2003]. All of the identified mutations in SCN4A are located in the coding regions (exons), and the mutant Nav1.4 channels show gain-of-function defects, such as disruption of fast inactivation and/or enhancement of activation [Cannon SC, 2006]. To our knowledge, no mutations in SCN4A have been reported in non-coding regions (introns). Although disease-associated mutations located in non-coding regions have been identified in other voltage-gated ion channel genes, they generally show loss-of-function defects [Colding-Jorgensen E, 2005; Dutzler R et al., 2002; Ruan Y et al., 2009; Zimmer T and Surber R, 2008].

Pre-mRNA splicing relies on conserved, yet highly diverse sequence elements at both ends of introns, termed splice sites [Brow DA, 2002]. The vast majority of introns are bounded by GT-AG dinucleotides, and are usually recognized and spliced by the major or U2-type spliceosome, which comprises the U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) [Sheth N et al., 2006]. In contrast, AT-AC introns are rare (0.34 %) and usually spliced by the minor or U12-type spliceosome, comprising U11, U12, U4atac, U5 and U6atac snRNPs [Burge CB et al., 1998; Patel AA and Steitz JA, 2003; Sheth N et al., 2006]. AT-AC introns occur frequently in voltage-gated ion channel genes, such as intron 2 and intron 21 in SCN4A [Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1996; Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1997; Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1999]. However, whereas intron 2 is spliced by the minor spliceosome, intron 21 is spliced by the major or U2-type spliceosome. Thus, intron 2 is classified as AT-AC type I, and intron 21 as AT-AC type II [Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1996; Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1997]. Analogously, a small subset of GT-AG introns spliced by the minor spliceosome, further demonstrating that the terminal intronic dinucleotides do not hold enough information to determine their mechanism of recognition [Burge CB et al., 1998; Dietrich RC et al., 1997; Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1997]. A recent genomic study estimated only 15 AT-AC type II introns in the human genome (out of ∼2×105 introns), confirming that these introns are extremely rare [Sheth N et al., 2006]. Furthermore, 10 out of the 15 AT-AC type II introns are found in members of the Nav channel gene family, and clearly have a common evolutionary origin [Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1997; Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1999].

We found a patient with prominent myotonia caused by a deletion/insertion located in intron 21 of one of the SCN4A alleles. This is the first disease-associated mutation in the very rare class of AT-AC type II introns. The patient's skeletal muscle expressed aberrantly spliced SCN4A mRNA isoforms by activation of cryptic splice sites, and we observed the same aberrant splicing patterns when we tested mutant SCN4A minigenes. We further showed that the aberrantly spliced isoform encodes a channel with a 35-amino-acid insertion in the cytoplasmic loop, and this mutant channel exhibited a marked disruption of fast inactivation. In addition, we showed, using in silico simulation, that the defect of the channel is consistent with the patient's myotonic symptoms. This is the first case of a gain-of-function intronic mutation in a voltage-gated ion-channel gene.

Materials and Methods

Patient

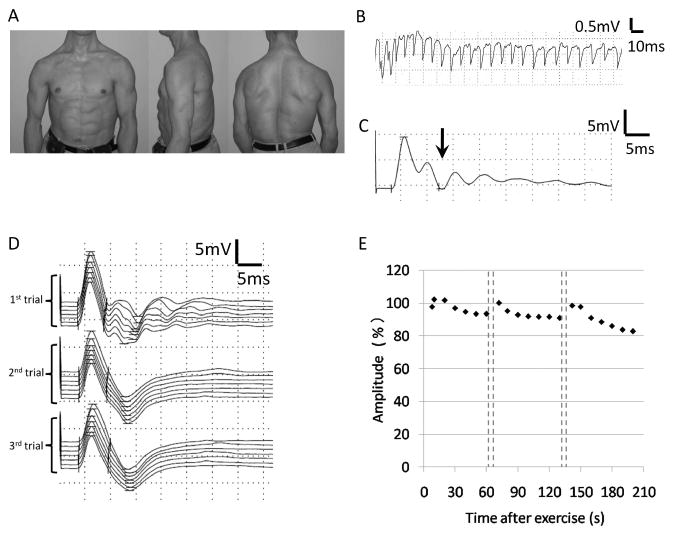

The patient was a 35-year-old Japanese male with hypertrophic musculature (Figure 1A). His family was not consanguineous and had no history of neuromuscular diseases. Due to myotonia, he had difficulties in opening his eyes and presented narrow palpebral fissures, which were exacerbated by repetitive contractions (eyelid paramyotonia). His distal extremities were atrophic and he had grade 2 of muscle strength in the arms and grade 4 in the legs. Scoliosis was present and articular contractures were noted in shoulders, elbows and wrists. Percussion myotonia in abductor pollicis brevis and rectus abdominus muscles and grip myotonia were present (Supp. Movie S1, S2). Myotonia was exacerbated by cold exposure but not by intake of fruits. He also had difficulty in breathing, which probably was caused by myotonia of respiratory muscles. Administration of mexiletine alleviated his myotonic symptoms, including the difficulty in breathing. More detailed medical history is given in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1. Clinical features of the patient.

A) Images showing the hypertrophic upper body musculature of the patient. B) Needle electromyography recording of tibialis anterior muscle showed myotonic discharge. C) Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) recorded from abductor digiti minimi muscle showed postexercise myotonic potentials (PEMPs) (arrow). D) Traces of CMAP during the repeated short exercise test. PEMPs were observed in the first trial recording after 10 s exercises, but disappeared with repeated exercises. E) A gradual decrease of the amplitude of CMAPs was observed with repeated short exercise.

Clinical electrophysiological examination

Clinical electrophysiological examinations were performed using Neuropack MEB 2216 (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). In brief, needle electromyography was performed with biceps brachii, extensor digitrum communis and tibialis anterior muscles using a concentric recording needle with a sampling frequency of 10 Hz – 10 kHz. The compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) of abductor digiti minimi were evoked by supramaximal stimulation of the ulnar nerve for 0.2 ms. The repeated short exercise test was performed as previously reported [Fournier E et al., 2004; Fournier E et al., 2006].

Pathological examination

After obtaining informed consent, a muscle specimen was extracted from the gluteus maximus muscle during surgery for a femur neck fracture. The specimens were snap-frozen in isopentane cooled with dry ice, and stored at -80 °C. Sections were stained with a battery of histochemical methods, including hematoxylin-eosin (H & E), ATPase (pH 10.2, pH 4.6 and pH 4.2) and acetylcholinesterase (AChE).

DNA sequencing

We obtained informed consent from patients and family members enrolled in the study, using protocols approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board at Osaka University. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood leukocytes from the patient and both parents. The regions encompassing all SCN4A (NM_000334.4) and CLCN1 (NM_000083.2) exons were amplified by PCR (primer sequences and their location from the end of each exon are shown in Supp. Table S1), and the purified fragments were sequenced using an automated DNA sequencer (Big Dye Terminator v 3.1 and ABI310; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). The PCR products including exon 21 and intron 21 were subcloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and the nucleotide sequences of both alleles were determined. Nucleotide numbering reflects cDNA numbering with +1 corresponding to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, according to journal guidelines (www.hgvs.org/mutnomen). The translation initiation codon is codon 1.

mRNA analysis

In addition to biopsied muscle from the patient, muscle specimens from myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients (n=3) were used as disease controls. Total RNA was extracted from each sample using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized from 1.8 μg of total RNA using random hexamers, and the cDNAs were amplified by 35 cycles of PCR (primer sequences in Supporting Information). The sizes of the PCR products were analyzed by agarose-gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide, and the fluorescent intensity of each band was quantified using FluoroImager (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, Connecticut). The RT-PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector, and the plasmids were transformed into competent E. coli (ECOS™ Competent E.Coli XL1-Blue, Nipongene, Tokyo, Japan). A total of 42 colonies were purified and sequenced.

Minigene construction and transient transfection

The genomic fragment encompassing SCN4A exon 20 to exon 22 was amplified using the patient's genomic DNA (primer sequences in Supporting Information). Purified wild-type and mutant PCR fragments were cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen). Clones were sequenced to exclude the presence of additional mutations.

U1 and U6 expression plasmids are described elsewhere [Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009]. Mutations at the 5′ end of U1 or at the conserved U6 ACAGAG box were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% (v/v) FBS and antibiotics (100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin). We mixed 80 ng of the SCN4A minigenes with 400 or 800 ng of the U1 and U6 plasmids, and with 80 ng of the pEGFP-N1 plasmid (Clontech). HeLa cells were transfected with the plasmid mixes using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics) as previously reported [Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009]. RNA was harvested 48 h after transfection using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Residual DNA was eliminated with RQ1-DNase (Promega), and the RNA was recovered by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. A total of 1 μg of RNA was used for reverse transcription with Superscript II RT (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT as a primer.

The minigene cDNAs were amplified by PCR using primers located in the transcribed portion of the pcDNA3.1+ plasmid [Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009]. The 5′ end of one of the PCR primers was radiolabeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and γ-32P-ATP, and the primer was purified using MicroSpin G-25 columns (GE Healthcare). A total of 23 cycles of PCR were performed to ensure that amplification remained in the exponential phase. The PCR products were separated by 6% native PAGE, and the gels were exposed on BioMAX XAR film (Kodak). The identity of each band was determined by cloning of separate non-radioactive RT-PCR products into the Original TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen) followed by sequencing on an ABI3730 automated sequencer.

Construction of expression vector for the aberrantly spliced isoform

PCR of the patient's cDNA was performed using primers shown in the Supporting Information. An Sse83871 (TaKaRa, Japan)-digested fragment of the PCR product was cloned into a mammalian expression construct for the human skeletal muscle sodium channel, pRc/CMV-hSkM1 [Takahashi MP and Cannon SC, 1999].

Na-current recording using cultured cells

Cultures of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and their transient transfection were performed as described [Green DS et al., 1998; Takahashi MP and Cannon SC, 1999]. In brief, plasmid cDNAs that encoded wild-type (0.8 μg/35-mm dish) or mutant human Na channel α-subunits (1.6 μg/35-mm dish), the human Na channel β-subunit (four-fold molar excess over α-subunit DNA), and a CD8 marker (0.1 μg/35-mm dish) were used to co-transfect HEK-293T cells by the calcium phosphate method. Transfection-positive cells are identified by attachment of CD8 antibody-coated beads (Dynal, Oslo Norway).

For measuring the current density, the same amount of α-subunit plasmids (1.6 μg/35-mm dish) were used for both wild-type and mutant channels. For the kinetic analyses, the amount of wild type plasmid for transfection was reduced to one half of that of the mutant channel, because of the higher expression level of the wild-type channel.

At 2-3 days after transfection, we measured sodium currents using conventional whole-cell recording techniques with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, CA). Any cells with peak currents of < 0.5 or > 15 nA on step depolarization from -120 mV to -10 mV were discarded. The pipette (internal) solution consisted of: 105 mM CsF, 35 mM NaCl, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM Cs-HEPES (pH 7.4). The bath solution consisted of: 140 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, and 10 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.4).

The current density (pA/pF) was calculated using the capacitance of each cell and the peak current elicited by a depolarization pulse of -10 mV from a holding potential of -120 mV. The voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation was measured as the peak current elicited after a 300-ms conditioning pulse from a holding potential of -120 mV. The voltage dependence of steady-state slow inactivation was measured as the peak current elicited by the test pulse after a 60-s conditioning prepulse, followed by a 20-ms gap at -120 mV to allow recovery from fast inactivation. The kinetics of the fast inactivation was characterized by measuring the voltage dependence of the time constant using three different protocols: (i) the current decay in the depolarized range; (ii) the entry protocol in the intermediate ranges; and (iii) the recovery protocol in the hyperpolarized range.

Data analysis

Curve fitting was manually performed off-line using Origin (Microcal LLC, Northampton, MA). Conductance was calculated as G(V) = Ipeak (V)/(V–Erev), where the reversal potential, Erev, was measured experimentally for each cell. The voltage dependence of activation was quantified by fitting the conductance measures to a Boltzmann function as G(V) = Gmax/[1 + exp(–(V–V1/2)/k)]. Steady-state fast inactivation was fitted to a Boltzmann function calculated as I/Imax = 1/[1 + exp ((V–V1/2)/k)], where V1/2 was the half-maximum voltage and k was the slope factor. Steady-state slow inactivation was fitted to a Boltzmann function with the non-zero pedestal (S0). Symbols with error bars indicate the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test with Origin.

Simulation

Computer simulations of skeletal muscle were performed using the model previously reported by Cannon et al., with minor modifications [Cannon SC et al., 1993]. The model included potassium and sodium channels described with the Hodgkin-Huxley model and leak-current on the two electrically-connected compartments (cell surface and the membrane of T-tubule system). We coded the model with Excel Visual Basic Application (Microsoft). Parameter values used for the wild type were identical with those reported previously [Hayward LJ et al., 1996]. Parameters for fast inactivation of the mutant channel were estimated from the fit of experimental data with a two-state model.

Results

Clinical electrophysiology and muscle histopathology

The patient was evaluated with clinical electrophysiologicalmethods. Myotonic discharges were present in all muscles examined by needle electromyography (Figure 1B). The repeated short exercise test was performed to discriminate between myotonia caused by either Na or Cl channel mutations. After short exercises, abnormal sustained responses following the initial compound muscle action potential (CMAP) were observed, which were previously reported as post-exercise myotonic potentials (PEMPs) (Figure 1C) [Fournier E et al., 2004; Fournier E et al., 2006]. During the repeated short exercise test, PEMPs disappeared (Figure 1D) and the amplitude of CMAP decreased gradually (Figure 1E). The observed post-exercise decrease of electrical muscle response at room temperature was suggestive of myotonia caused by a Na-channel mutation.

Pathological examination of the biopsied muscle showed a myopathic change with marked variation in fiber size. Hypertrophic fibers with multiple internal nuclei were abundant. Type 1 fiber predominance and type 2B fiber deficiency were seen upon myosin ATPase staining (Supp. Figure S1A-D). Acetylcholinesterase (AchE) activity was increased in the sarcolemma (Supp. Figure S1E).

Analysis of genomic DNA and mRNA splicing isoforms

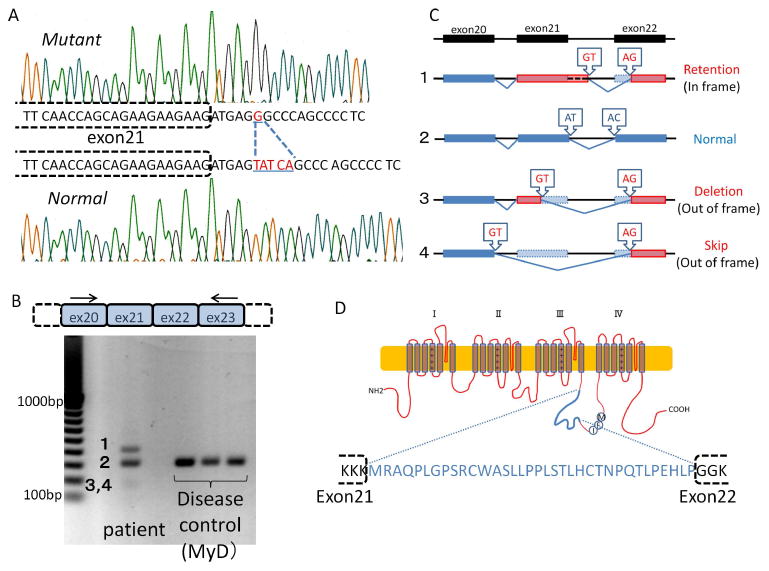

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the patient's DNA showed no mutation in any exons of SCN4A and CLCN1. On electrophoregram, however, two overlapping traces were consistently observed, starting from the sixth nucleotide downstream from the boundary between exon 21 and intron 21 of SCN4A (Supp. Figure S2A). To analyze the sequences of each strand, the PCR products encompassing exon 21 and intron 21 were subcloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector. Sequence analysis of each strand revealed a heterozygous mutation in intron 21, which consists of a five-nucleotide deletion and one-nucleotide insertion at the sixth nucleotide downstream from the boundary between exon 21 and intron 21 (NG_011699.1:c.3912+6_3912+10delinsG) (Figure 2A). Neither his parents nor 220 normal alleles harbored this mutation (Supp. Figure S2A).

Figure 2. Genomic DNA and mRNA analysis.

A) Both alleles of the patient's genomic DNA sequences around the boundary between exon 21 and intron 21 of SCN4A are separately shown. Deletion of five nucleotides (TATCA) and insertion of one nucleotide (G) were observed in one allele (c.3912+6_3912+10delinsG). B) RT-PCR from patient muscle mRNA revealed several aberrantly spliced isoforms, in addition to the normal isoform expressed in the disease control. Numbered bands (1-4) correspond to the isoforms in Figures 2C and 3C. Arrows indicate the primers used for RT-PCR. C) Summary of the sequence analysis of all isoforms. Lines indicate introns, and dark blue or red boxes indicate normal or aberrant exons, respectively. Light blue boxes indicate portions of the normal exons that were removed in the aberrant isoforms. Arrowhead rectangles indicate the splice-site dinucleotides. D) Schematic illustration of the mutant Nav 1.4 channel α subunit. The in-frame isoform encodes a large insertion (amino acids in blue type) in the domain III and IV linker.

Since this mutation affects a portion of the 5′ splice site, we hypothesized that it might influence the splicing of intron 21. To examine the splicing patterns of the mutant transcript, RT-PCR was performed using mRNA extracted from skeletal muscle. In control muscles, only a fragment with the expected size (325 nucleotides) was observed. In muscle from the patient, however, two additional fragments were observed, one larger and the other smaller than normal. By measuring the fluorescent intensity of these bands, the proportion of each isoform was estimated as follows: large isoform: 33 %; normal isoform: 57 %; small isoform: 10 % (Figure 2B). To determine the nucleotide sequence, RT-PCR products were subcloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector. Sequence analysis showed that the smaller fragments consisted of two isoforms: one originated by splicing between a cryptic 5′ splice site in exon 21 and a cryptic 3′ splice site located at the initial portion of exon 22 (Deletion type: 2/42 colonies); the other one as a result of splicing from the 5′ splice site of exon 20 to the same cryptic 3′ splice site of exon 22 (Skip type: 8/42 colonies). Both small isoforms are predicted to be translated out of frame, with their reading frames interrupted by premature termination codons. The large isoform resulted from splicing between a cryptic 5′ splice site in intron 21 and the same cryptic 3′ splice site as above (Retention type: 4/42 colonies). This isoform is in frame (Figure 2C), and is predicted to encode a channel with a one-amino-acid deletion and 35-amino-acid insertion in the DIII-DIV linker of Nav1.4, which could retain some degree of functionality (Figure 2D, Supp. Figure S2B). It should also be noted that the AT-AC type II intron 21 was replaced with aberrant GT-AG introns in all the abnormal isoforms (Supp. Figure S3).

Minigene analysis confirms the molecular diagnosis of the SCN4A mutation

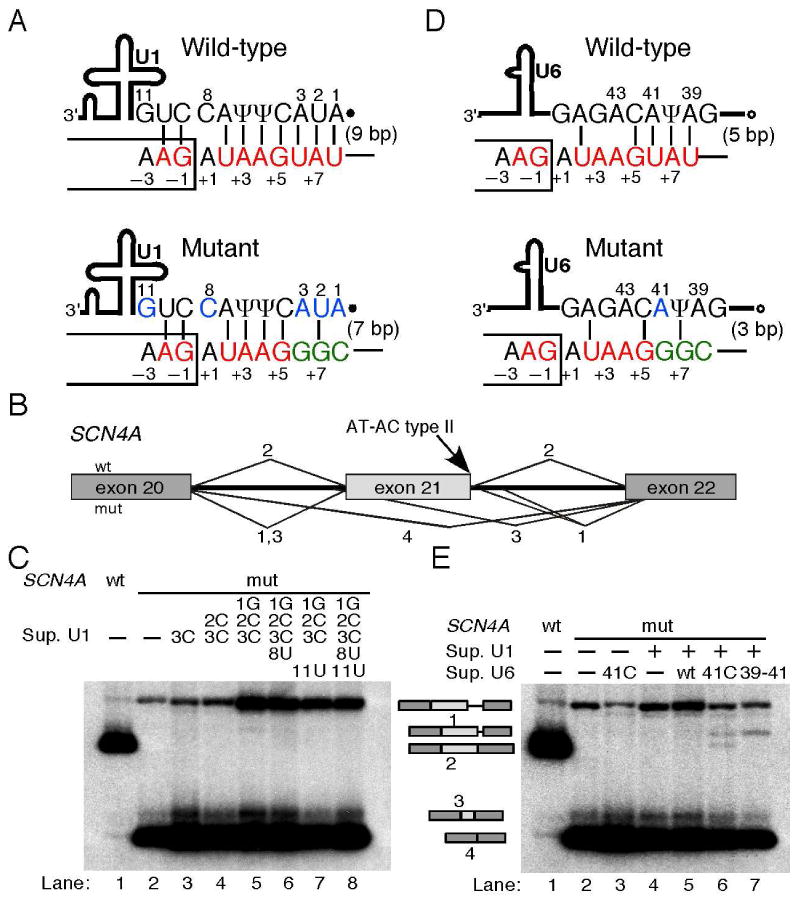

The deletion/insertion (TATCA>G) in intron 21 of one of the SCN4A alleles was a candidate mutation to cause the splicing defects associated with the patient's myotonia. This mutation affects position +6 (the sixth intronic nucleotide) of the 5′ splice site, which is one of the less conserved positions of GT-AG U2-type 5′ splice sites. In addition, the mutation also changes positions +7 and +8, which are not conserved at all in this class of 5′ splice sites. Nevertheless, these nucleotide changes at positions +6 to +8 reduce the base-pairing potential to the 5′ end of the U1 snRNA (Figure 3A), which is an early essential interaction for 5′-splice-site selection in U2-type introns [Seraphin B et al., 1988; Siliciano PG and Guthrie C, 1988; Zhuang Y and Weiner AM, 1986]. In addition, the mutation also disrupts base-pairing to the conserved ACAGAG box in U6 snRNA (Figure 3D), which replaces U1 later in spliceosome assembly [Kandels-Lewis S and Seraphin B, 1993; Lesser CF and Guthrie C, 1993; Wassarman DA and Steitz JA, 1992]. In any case, since this is the first disease-associated 5′-splice-site mutation in an AT-AC type II intron, additional evidence was necessary to unambiguously determine the pathogenicity of this mutation.

Figure 3. Mechanism of pathogenicity for the AT-AC type II intron mutation.

A) Schematic of the base-pairing between the wild type and mutant SCN4A intron 21 5′ splice site and the 5′ end of U1 snRNA. Thick line, U1 snRNA body; filled dot, trimethyl-guanosine cap; Ψ, pseudouridine. The box and the line depict portions of the exon and intron, respectively. Consensus and mutant nucleotides are shown in red and green, respectively. Nucleotides that were mutated in suppressor U1 snRNAs are shownin blue. The nucleotide positions at the 5′ splice site and at the 5′ end of U1 are numbered. Base-pairs are depicted as vertical lines, and the total number is indicated in parenthesis. B) Schematic of the normal and aberrantly spliced isoforms shown in panel C. Isoforms are numbered as in Figure 2. The location of the AT-AC type II 5′ splice site is indicated. C) Suppressor U1 snRNAs alone could not rescue splicing at the mutant 5′ splice site. The SCN4A minigene and suppressor U1 used are indicated above the autoradiograms. The various mRNAs are indicated on the right, and correspond to those seen in patient cells (Figure 2C). D) Schematic of the base-pairing between the wild type and mutant 5′ splice site and the conserved ACAGAG box of U6 snRNA. Open circle, γ-monomethyl cap. Font colors as in 3A. E) Suppressor U1 and U6 snRNAs partially rescue splicing at the mutant AT-AC type II 5′ splice site. The various constructs are indicated above the autoradiogram, and the identity of the mRNAs on the left. The U1 suppressor used was 1G2C3C, which together with the U6 suppressor 41C restored some correct splicing (lane 6).

We transiently transfected HeLa cells with the wild-type and mutant SCN4A minigenes, and analyzed the splicing patterns by radioactive RT-PCR, as well as by cloning and sequencing to confirm the identity of the PCR products. Both SCN4A minigenes recapitulated the splicing patterns seen in either control or patient cells, respectively (Figure 3B, C). The wild-type SCN4A minigene showed efficient splicing at the AT-AC type II boundaries, with traces of exon 21 skipping and activation of the cryptic GT-AG splice sites (Figure 3C, lane 1). In contrast, the mutant minigene showed no splicing at the AT-AC splice sites, but gave rise to the same three aberrantly spliced isoforms seen in patient cells. These results confirmed the molecular diagnosis of the SCN4A intron 21 TATCA>G mutation as the cause of the patient's myotonia (Figure 3C, lane 2).

The SCN4A mutation disrupts base-pairing to U1 and U6 snRNAs

We used genetic suppression analyses to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying defective splicing due to the mutation at the AT-AC type II 5′ splice site in SCN4A. We co-transfected cells with the SCN4A mutant minigene with suppressor U1 and/or U6 snRNAs carrying compensatory mutations that restore base-pairing to the mutant 5′ splice site [Cohen JB et al., 1994; Mount SM and Anderson P, 2000; Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009; Seraphin B et al., 1988; Siliciano PG and Guthrie C, 1988; Zhuang Y and Weiner AM, 1986]. None of the multiple suppressor U1s carrying one or several compensatory mutations could rescue correct splicing at the AT-AC boundaries (Figure 3C, lanes 3-8). In previous U1-suppressor experiments for U2-type GT-AG 5′ splice sites, restoring base-pairing to U1 snRNA alone was sufficient to rescue correct splicing [Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009; Seraphin B et al., 1988; Siliciano PG and Guthrie C, 1988; Zhuang Y and Weiner AM, 1986], suggesting that the mutation at the SCN4A AT-AC type II 5′ splice site critically affects other recognition steps. The U6 suppressors alone could not rescue correct AT-AC splicing either (Figure 3E lane 3, and data not shown), in contrast to what was previously seen with mutant U2-type GT-AG 5′ splice sites [Carmel I et al., 2004; Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009]. Interestingly, combining certain suppressor U1 and U6 snRNAs rescued splicing via the AT-AC splice sites, albeit weakly (Figure 3E lane 6). This weak restoration of correct splicing could not be augmented by using different combinations of U1 and U6 suppressors, or by introducing additional compensatory mutations in U6 (Figure 3E lane 7, and data not shown). In some cases, a cryptic GT-AG splice-site pair was activated (Figure 3C lane 5, and Figure 3E lanes 6 and 7), for unknown reasons. Taken together, these results suggest that the SCN4A intron 21 TATCA>G mutation disrupts optimal base-pairing to both U1 and U6 snRNAs.

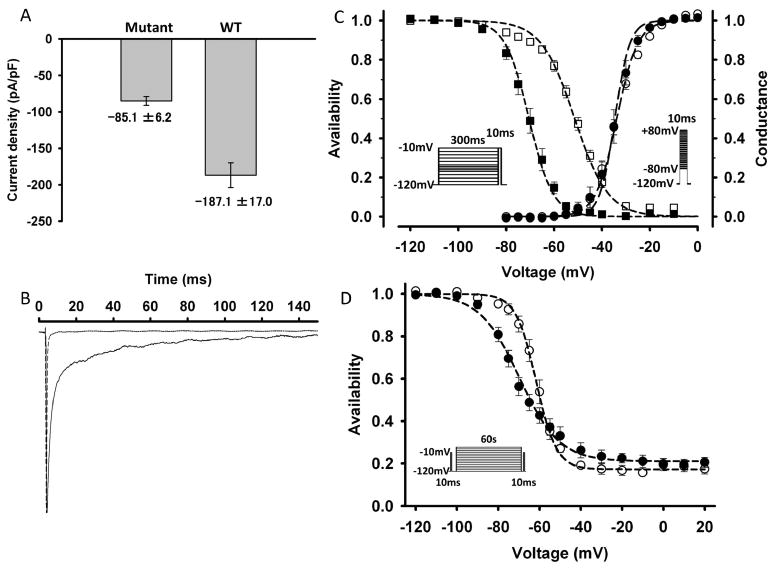

Current density and gating of the mutant channel

We examined the functional consequences of this aberrant splicing by recording whole-cell Na currents from HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with the mutant Na channel cDNA. The current density of the mutant channel was approximately half that of the wild type (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Current density and gating of the mutant channel.

A) The current density (pA/pF) of the mutant channel (n=39) is approximately half that of wild-type (n=9) when the same amount of the corresponding expression plasmids was used for transfection. Error bars indicate S.E.M. B) Normalized macroscopic sodium current elicited by a depolarization pulse of -10 mV from a holding potential of -120 mV. The mutant channel (solid line) showed slower decay than the wild type (dotted line), suggesting a disruption of fast inactivation. C) Voltage dependence of availability (steady-state fast inactivation, left, squares) and conductance (activation, right, circles). Filled and open symbols represent the wild type and mutant channels, respectively. The midpoint of the steady-state fast inactivation curve for the mutant channel (V1/2) was shifted in the direction of depolarization by 19.1 mV, compared to that for the wild type. The insets show the protocols used to measure the voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation (left) and the conductance (right). D) The voltage dependence of steady-state slow inactivation for the wild type channel (filled symbols) and mutant channel (open symbols). The maximum extent of slow inactivation does not differ between the wild type and mutant channels. The inset shows the protocol.

Figure 4B shows normalized macroscopic Na currents of both wild type and mutant channels, which were elicited by a depolarization pulse of -10 mV from a holding potential of -120 mV. The mutant channel current decayed more slowly than that of wild type, suggesting disruption of fast inactivation. The voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation measured with 300-ms conditioning pulse was shown in Figure 4C. The midpoint of the steady-state fast-inactivation curve for the mutant channel was shifted in the direction of depolarization by 19.1 mV compared to that of the wild type. The estimated parameters of steady-state fast inactivation were as follows: wild type: V1/2 = -70.4 ± 1.4 (n = 14), k = 5.0 ± 0.2 (n = 14); mutant: V1/2 = -51.3 ± 1.0 (n = 35), k = 7.0 ± 0.2 (n = 35) (Table 1). On the other hand, the voltage dependence of the mutant channel conductance was not different from that of the wild type (Figure 4C, Table 1).

Table 1. Parameter estimates for wild-type and mutant channels.

| Activation | Fast inactivation | Slow inactivation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2 | k | V1/2 | k | V1/2 | k | So | |

| (mV) | (mV/e-fold) | (mV) | (mV/e-fold) | (mV) | (mV/e-fold) | ||

| WT | -34.6±1.5 (14) | 3.1±0.3* (14) | -70.4±1.4* (14) | 5.0±0.2* (14) | -69.7±1.8* (9) | 9.6±0.7* (9) | 0.21±0.02 (9) |

| Mutant | -33.8±0.7 (35) | 4.4±0.2* (35) | -51.3±1.0* (35) | 7.0±0.2* (35) | -61.6±1.7* (7) | 4.9±0.3* (7) | 0.17±0.02 (7) |

V1/2 is the midpoint value of the steady-state inactivation curve and the voltage dependence of the conductance curve. k is the slope factor. S0 is the non-zero pedestal. Values are means ± S.E.M.

p<0.01

The voltage dependence of steady-state slow inactivation measured using a 60-s conditioning prepulse was shown in Figure 4D. The midpoint of the steady-state slow inactivation curve for the mutant channel was shifted in the direction of depolarization by 8.1 mV compared to that of the wild type. The slope factor for the mutant channel was steeper than that of the wild type. However, the maximum extent of slow inactivation (S0) did not differ between the wild type and mutant channels (Table 1).

The kinetics of the fast inactivation was characterized by measuring the voltage dependence of the time constant using three different protocols. The time constants were analyzed by a single-exponential fit (see Supp. Figure S4 for the analysis by two-exponential fit), in order to estimate the parameters of a two-state model, which are suitable for a simulation based on the Hodgkin-Huxley model. For the mutant channel, the voltage dependence of time constants was shifted in the direction of depolarization, and the time constants at the depolarized range were significantly slower (Supp. Figure S5). Subsequently, the forward and backward rates of two-state model were estimated from the voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation and the time constants. For the mutant channel, the estimated value for the forward rate (α) was approximately 4 times and the backward rate (β) was one-fifth of those for wild type. The detail of the analysis is described in the Supporting Information.

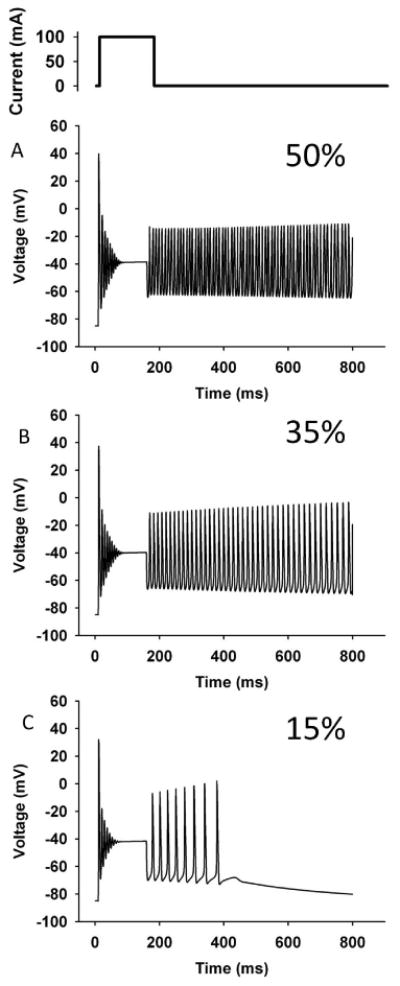

Computer simulation

Although the depolarized shift of steady-state fast-inactivation curve was consistent with enhanced membrane excitability, a computer simulation was performed to examine whether the functional defects of the mutant channel can recapitulate the symptoms, especially because the expression levels of the mutant channel could not be measured. The simulation based on the Hodgkin-Huxley model–which was previously reported by Cannon et al. was reconstructed with Visual Basic [Cannon SC et al., 1993]. All the gating parameters for the wild-type channel were the same as those previously reported by Hayward 1996 (Supp. Table S2) [Hayward LJ et al., 1996]. The parameters for fast inactivation of the mutant channel were modified based on the result in Supp. Figure S5. The fraction of the persistent current (f) for the mutant channel was estimated by averaging the currents in the last 5 ms of the 300-ms depolarization. All the other parameters for the mutant channel were identical to those for the wild type. The stimulating current was applied as a square wave (100 mA, 150 ms). Since the expression of the mutant channel is likely lower than that of the wild type, simulation studies were performed varying the proportion of the mutant channel. When the expressed Na channel was all wild type, repetitive firing of action potentials was not seen (data not shown). When the expression of the mutant channel was set at 50 % of the total Na channel, repetitive firing of action potentials was observed (Figure 5A). When the expression of the mutant channel was set at 35 %, repetitive firing of action potentials was still evoked (Figure 5B). Moreover, in the case of decreasing the expression of the mutant channel to 15%, repetitive firing of action potentials was still observed, although the degree of firing was not as robust (Figure 5C). Overall, the results of this simulation suggest that the functional defect of the channel is sufficient to cause myotonia, even when the expression of the mutant channel is as low as 15 % of the total SCN4A channel.

Figure 5. Computer simulation.

The upper inset indicates the stimulating current (100 mA, 150 ms). The simulation was performed by varying the proportion of the mutant channel, because the expression of the mutant channel in the patient's muscle is unknown (A: 50%; B: 35%; C: 15%). Repetitive firing of action potentials was observed even when expression of the mutant channel was set at 15 %.

Discussion

We have identified a causative mutation located in intron 21 of SCN4A in a patient with myotonia. The patient's myotonia was confirmed by needle electromyography, and was exacerbated by cold exposure and repetitive exercise (paramyotonia). Neurophysiological tests showed PEMPs and the characteristic decreasing of CMAPs with repeated short exercises [Fournier E et al., 2004; Fournier E et al., 2006]. The clinical features and the results of the neurophysiological tests are consistent with myotonia due to a defect in Nav1.4. Hereditary skeletal-muscle diseases caused by mutations in SCN4A have been classified into paramyotonia congenita (PMC; MIM# 168300), potassium-aggravated myotonia (PAM; MIM# 608390), and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HyperPP; MIM# 170500) [Cannon SC, 2006]. Furthermore, the most severe form of PAM is called myotonia permanens, for which the only causative mutation reported to date is G1306E [Lehmann-Horn F et al., 1990]. As the patient showed prominent generalized myotonia, associated with difficulty in breathing, hypertrophic musculature, joint contractures and scoliosis, we assumed that his clinical features were indicative of myotonia permanens. Although he presented myotonia exacerbated by cold exposure, and paramyotonia in the eyelids, two symptoms characteristic of PMC rather than PAM, several cases of PAM exacerbated by cold exposure have been reported. As mentioned above, classification of sodium-channel myotonic disorders is sometimes difficult, because of their clinical overlap. Recently, the Consortium of Clinical Investigators of Neurological Channelopathies has proposed that sodium-channel myotonic disorders might be simply classified into two broad groups, based on the presence or absence of episodic weakness: PMC or sodium-channel myotonia, respectively [Matthews E et al., 2010]. According to this proposal, our case might be classified into sodium-channel myotonia, because of the lack of clear episodic weakness. Another clinical feature of interest is muscle atrophy in distal upper extremities. However, this would not exclude non-dystrophic myotonia. In fact, dystrophic features have been reported in myotonia caused by Na-channel and Cl-channel mutations [Kubota T et al., 2009; Nagamitsu S et al., 2000; Plassart E et al., 1996; Schoser BG et al., 2007].

From a clinicogenetic point of view, this mutation is unprecedented in two ways. First, this is the first disease-associated intronic mutation in a voltage-gated ion channel gene showing a gain-of-function defect. Many different mutations in voltage-gated ion channel genes have been identified as causes for inherited disorders, but these mutations mostly map to the coding exons [Cannon SC, 2006; George AL, Jr., 2005]. A few disease-associated mutations in non-coding regions of voltage-gated ion channel genes have been reported. For example, at least six mutations associated with autosomal-recessive (Becker) myotonia congenita have been identified in non-coding regions of the skeletal-muscle chloride-channel gene, CLCN1 [Colding-Jorgensen E, 2005]. Similarly, at least seven mutations causing Brugada syndrome have been identified in the non-coding regions of the cardiac muscle sodium-channel gene SCN5A [Ruan Y et al., 2009; Zimmer T and Surber R, 2008]. Notably, mutant channels causing Becker-type myotonia congenita and Brugada syndrome generally exhibit loss-of-function defects. Moreover, a splice-site mutation in the neuronal sodium channel SCN1A was identified in a patient with partial epilepsy with febrile seizures, although the properties of the mutant channel have not been assessed [Kumakura A et al., 2009]. Here we described a heterozygous mutation in a non-coding region of SCN4A that causes aberrant splicing. Our results strongly suggest that one of the aberrantly spliced mRNA isoforms is translated into a functional channel that displays a gain-of-function defect. Therefore, our case constitutes a novel mechanism of pathogenesis for inherited channelopathies.

Second, the deletion/insertion in intron 21 of SCN4A is the first disease-associated mutation identified in a very rare class of introns, known as AT-AC type II. An intronic mutation in the other, more common type of AT-AC intron (AT-AC type I, or U12-dependent) in the LKB1 gene was found to cause Peutz-Jeghers syndrome [Hastings ML et al., 2005]. No disease-associated mutation in AT-AC type II introns had been described until now, probably because of the very low number (only 15) of such introns in the human genome [Sheth N et al., 2006]. Since 10 out of 15 AT-AC type II introns are found in members of Nav-channel gene family, other mutations in these introns may be found to be associated with channelopathies in the future.

The splicing defects caused by the SCN4A intron 21 mutation were confirmed by minigene analysis. The splicing patterns from the wild-type and mutant SCN4A minigenes faithfully matched those seen in control and patient cells, respectively. The disruption of the AT 5′ splice site resulted in aberrantly spliced mRNAs by activation of cryptic GT-AG pairs. This observation is consistent with the notion that AT 5′ splice sites are almost exclusively paired with AC 3′ splice sites [Dietrich RC et al., 1997; Parker R and Siliciano PG, 1993; Sheth N et al., 2006; Wu Q and Krainer AR, 1997].

Our genetic suppression experiments provided a mechanistic basis for the pathogenic effect of the deletion/insertion in intron 21. These tests suggested that the mutant AT-AC type II 5′ splice site is defective in efficient base-pairing to both U1 and U6 snRNAs, which are key splicing factors that sequentially bind U2-type 5′ splice sites. This might constitute a fundamental difference between AT-AC type II and GT-AG 5′ splice sites, in that 5′ splice-site mutations in GT-AG introns can usually be rescued by suppressor U1s alone [Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009; Seraphin B et al., 1988; Siliciano PG and Guthrie C, 1988; Zhuang Y and Weiner AM, 1986], whereas in this case we only observed weak rescue when both U1 and U6 suppressors were expressed simultaneously. Further U1/U6 suppressor analysis using other AT-AC type II introns is needed to confirm the generality of the U6 dependence of SCN4A AT-AC type II introns.

Interestingly, the AT-AC type II mutation results in activation of cryptic U2-type GT-AG splice-site pairs, similarly to what was seen upon mutations in minor-spliceosome or U12-type introns [Hastings ML et al., 2005; Incorvaia R and Padgett RA, 1998; Kolossova I and Padgett RA, 1997]. These cryptic GT-AG pairs are present in the wild-type pre-mRNA, but remain silent unless one of the AT-AC splice sites is mutated. Whereas GT-AG U2-type splice sites exhibit a very high degree of variation, with thousands of different sequences acting as functional splice sites in the human genome [Roca X and Krainer AR, 2009], U12-type splicing elements (specifically the 5′ splice site and the branch point sequence) are very highly conserved, suggesting that these sequences are constrained to be functional [Sheth N et al., 2006]. Our observations suggest that AT-AC type II introns are similarly constrained, and that one of these constraints might be the need for efficient base-pairing to U6 snRNA, possibly because of the G>A difference at the first intronic position. It remains possible that there are specific splicing elements and factors required for efficient splicing of AT-AC type II introns, but these are not identifiable by genomic analyses because of the very low number of such introns. In short, mutations that disrupt AT-AC type II splice sites, like those affecting U12-type splice sites, result in activation of cryptic U2-type GT-AG splice sites, because the sequence requirements for these U2-type GT-AG splice sites are much more flexible.

The functional properties of the aberrantly spliced channel provide further understanding about the molecular mechanism of fast inactivation of the sodium channel. It has been established that the DIII-DIV linker plays a key role in fast inactivation of sodium channels. In particular, a cluster of hydrophobic amino acids (IFM) in the DIII-DIV linker is believed to function as an essential component of the fast inactivation particle, which occludes the intracellular mouth of the activated channel by a “ball-and-chain” or “hinged-lid” mechanism [Armstrong CM and Bezanilla F, 1977; West JW et al., 1992]. In Nav1.4, the DIII-DIV linker comprises 92 amino acids, but there are only 15 residues between the end of DIIIS6 and the IFM motif. To properly occlude the intracellular mouth of the channel, 10-20 residues between the end of DIIIS6 and the IFM motif are supposed to be optimal to form the hinged-lids structures [West JW et al., 1992]. The mutant sodium channel expressed in our patient's muscle has an insertion of 34 amino acids preceding the IFM motif, and showed disruption of fast inactivation. Considering the number of residues between the end of DIIIS6 and the IFM motif, the 34-amino-acid insertion is probably too large and may give the “lid” more freedom of movement. Indeed, it has been reported that even a 12-amino-acid insertion into the 5′end of the DIII-DIV linker (9 residues) and the beginning part of DIVS1 (3 residues) causes disruption of fast inactivation [Patton DE and Goldin AL, 1991]. Therefore, it is highly possible that the elongated loop in our mutant channel does not properly function as the hinged lid, resulting in the disruption of fast inactivation.

The abnormally spliced channel expressed in cell culture showed disruption of fast inactivation, which is consistent with the hyperexcitability of the patient's skeletal muscle. In the case of heterozygous mutations located in coding regions (missense mutations), the proportion of the mutant channel might be expected to be half of the total channel, assuming equal expression. In the heterozygous patient described here, however, the expression of the aberrantly spliced mutant channel is likely less than half of the total channel. The proportion of mRNA coding for the abnormal channel was roughly estimated from the fluorometric measurement of the PCR fragments (Figure 2B). The abundance of the mRNA for the mutant channel isoform was about 60 % that of the normal isoform (Figure 2B). The other mRNA isoforms were out-of frame and introduced premature termination codons, so they are likely to be partially degraded by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [Chang YF et al., 2007]. However, it is not certain whether the mutant channel is translated, correctly folded, and targeted to the plasma membrane as efficiently as the wild type. Indeed, the current density of mutant channel was about half that of wild type when expressed in HEK-293T cells, although this might also reflect a difference in the open probability between wild type and mutant channels. Simply by multiplying the two numbers above, the expression ratio between the wild type and mutant channels was estimated at 10: 3. Computer simulation varying the expression level of the mutant showed that repetitive firing of action potentials (myotonia) is observed even if the expression of the mutant channel is set at 15 % (Figure 5). Taken together, the most likely explanation for our observations is that the functional defect of the mutant channel caused by aberrant splicing is sufficient to cause the patient's myotonic symptoms.

In summary, we have identified a rare non-dystrophic myotonia caused by a mutation in the AT-AC type II intron in SCN4A. Our experiments also contribute to a better understanding of the splicing mechanisms for a very rare class of introns. Henceforth, the inherited channelopathies caused by mutations in non-coding regions should be investigated more vigorously.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Intramural Research Grant for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry 20B-13, Research Grants for Intractable Disease from the Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the JSPS, and grant from the Nakatomi Foundation to M.P.T. and by the National Institutes of Health GM42699 to X.R. and A.R.K.. The authors thank Dr. Steve Cannon for providing the expression vectors, Dr. Ryuzo Mizuno for referring the patient, and Ms. Mieko Tanaka for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this preprint is available from the Human Mutation editorial office upon request (humu@wiley.com)

References

- Armstrong CM, Bezanilla F. Inactivation of the sodium channel. II. Gating current experiments. J Gen Physiol. 1977;70:567–590. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brow DA. Allosteric cascade of spliceosome activation. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:333–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.043002.091635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge CB, Padgett RA, Sharp PA. Evolutionary fates and origins of U12-type introns. Mol Cell. 1998;2:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC. Pathomechanisms in channelopathies of skeletal muscle and brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:387–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC, Brown RH, Jr, Corey DP. Theoretical reconstruction of myotonia and paralysis caused by incomplete inactivation of sodium channels. Biophys J. 1993;65:270–288. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel I, Tal S, Vig I, Ast G. Comparative analysis detects dependencies among the 5′ splice-site positions. RNA. 2004;10:828–840. doi: 10.1261/rna.5196404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YF, Imam JS, Wilkinson MF. The nonsense-mediated decay RNA surveillance pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:51–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.050106.093909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JB, Snow JE, Spencer SD, Levinson AD. Suppression of mammalian 5′ splice-site defects by U1 small nuclear RNAs from a distance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10470–10474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colding-Jorgensen E. Phenotypic variability in myotonia congenita. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:19–34. doi: 10.1002/mus.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich RC, Incorvaia R, Padgett RA. Terminal intron dinucleotide sequences do not distinguish between U2- and U12-dependent introns. Mol Cell. 1997;1:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier E, Arzel M, Sternberg D, Vicart S, Laforet P, Eymard B, Willer JC, Tabti N, Fontaine B. Electromyography guides toward subgroups of mutations in muscle channelopathies. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:650–661. doi: 10.1002/ana.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier E, Viala K, Gervais H, Sternberg D, Arzel-Hezode M, Laforet P, Eymard B, Tabti N, Willer JC, Vial C, Fontaine B. Cold extends electromyography distinction between ion channel mutations causing myotonia. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:356–365. doi: 10.1002/ana.20905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George AL., Jr Inherited disorders of voltage-gated sodium channels. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1990–1999. doi: 10.1172/JCI25505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DS, George AL, Jr, Cannon SC. Human sodium channel gating defects caused by missense mutations in S6 segments associated with myotonia: S804F and V1293I. J Physiol. 1998;510(Pt 3):685–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.685bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings ML, Resta N, Traum D, Stella A, Guanti G, Krainer AR. An LKB1 AT-AC intron mutation causes Peutz-Jeghers syndrome via splicing at noncanonical cryptic splice sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:54–59. doi: 10.1038/nsmb873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward LJ, Brown RH, Jr, Cannon SC. Inactivation defects caused by myotonia-associated mutations in the sodium channel III-IV linker. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:559–576. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incorvaia R, Padgett RA. Base pairing with U6atac snRNA is required for 5′ splice site activation of U12-dependent introns in vivo. RNA. 1998;4:709–718. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandels-Lewis S, Seraphin B. Involvement of U6 snRNA in 5′ splice site selection. Science. 1993;262:2035–2039. doi: 10.1126/science.8266100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolossova I, Padgett RA. U11 snRNA interacts in vivo with the 5′ splice site of U12-dependent (AU-AC) pre-mRNA introns. RNA. 1997;3:227–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T, Kinoshita M, Sasaki R, Aoike F, Takahashi MP, Sakoda S, Hirose K. New mutation of the Na channel in the severe form of potassium-aggravated myotonia. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:666–673. doi: 10.1002/mus.21155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumakura A, Ito M, Hata D, Oh N, Kurahashi H, Wang JW, Hirose S. Novel de novo splice-site mutation of SCN1A in a patient with partial epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Brain Dev. 2009;31:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann-Horn F, Iaizzo PA, Franke C, Hatt H, Spaans F. Schwartz-Jampel syndrome: II. Na+ channel defect causes myotonia. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:528–535. doi: 10.1002/mus.880130609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser CF, Guthrie C. Mutations in U6 snRNA that alter splice site specificity: implications for the active site. Science. 1993;262:1982–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.8266093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews E, Fialho D, Tan SV, Venance SL, Cannon SC, Sternberg D, Fontaine B, Amato AA, Barohn RJ, Griggs RC, Hanna MG. The non-dystrophic myotonias: molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Brain. 2010;133:9–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount SM, Anderson P. Expanding the definition of informational suppression. Trends Genet. 2000;16:157. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamitsu S, Matsuura T, Khajavi M, Armstrong R, Gooch C, Harati Y, Ashizawa T. A “dystrophic” variant of autosomal recessive myotonia congenita caused by novel mutations in the CLCN1 gene. Neurology. 2000;55:1697–1703. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Siliciano PG. Evidence for an essential non-Watson-Crick interaction between the first and last nucleotides of a nuclear pre-mRNA intron. Nature. 1993;361:660–662. doi: 10.1038/361660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AA, Steitz JA. Splicing double: insights from the second spliceosome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:960–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton DE, Goldin AL. A voltage-dependent gating transition induces use-dependent block by tetrodotoxin of rat IIA sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neuron. 1991;7:637–647. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90376-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassart E, Eymard B, Maurs L, Hauw JJ, Lyon-Caen O, Fardeau M, Fontaine B. Paramyotonia congenita: genotype to phenotype correlations in two families and report of a new mutation in the sodium channel gene. J Neurol Sci. 1996;142:126–133. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca X, Krainer AR. Recognition of atypical 5′ splice sites by shifted base-pairing to U1 snRNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:176–182. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Y, Liu N, Priori SG. Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoser BG, Schroder JM, Grimm T, Sternberg D, Kress W. A large German kindred with cold-aggravated myotonia and a heterozygous A1481D mutation in the SCN4A gene. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:599–606. doi: 10.1002/mus.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin B, Kretzner L, Rosbash M. A U1 snRNA:pre-mRNA base pairing interaction is required early in yeast spliceosome assembly but does not uniquely define the 5′ cleavage site. EMBO J. 1988;7:2533–2538. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth N, Roca X, Hastings ML, Roeder T, Krainer AR, Sachidanandam R. Comprehensive splice-site analysis using comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3955–3967. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siliciano PG, Guthrie C. 5′ splice site selection in yeast: genetic alterations in base-pairing with U1 reveal additional requirements. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1258–1267. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.10.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi MP, Cannon SC. Enhanced slow inactivation by V445M: a sodium channel mutation associated with myotonia. Biophys J. 1999;76:861–868. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujino A, Maertens C, Ohno K, Shen XM, Fukuda T, Harper CM, Cannon SC, Engel AG. Myasthenic syndrome caused by mutation of the SCN4A sodium channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7377–7382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230273100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman DA, Steitz JA. Interactions of small nuclear RNA's with precursor messenger RNA during in vitro splicing. Science. 1992;257:1918–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.1411506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JW, Patton DE, Scheuer T, Wang Y, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. A cluster of hydrophobic amino acid residues required for fast Na(+)-channel inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10910–10914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Krainer AR. U1-mediated exon definition interactions between AT-AC and GT-AG introns. Science. 1996;274:1005–1008. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Krainer AR. Splicing of a divergent subclass of AT-AC introns requires the major spliceosomal snRNAs. RNA. 1997;3:586–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Krainer AR. AT-AC pre-mRNA splicing mechanisms and conservation of minor introns in voltage-gated ion channel genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3225–3236. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Weiner AM. A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA suppresses a 5′ splice site mutation. Cell. 1986;46:827–835. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer T, Surber R. SCN5A channelopathies--an update on mutations and mechanisms. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.