Abstract

Objective

To describe human capacity and staff movement in national health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries.

Design

A structured questionnaire was used to solicit information on governance and stewardship from health research institutions.

Setting

Eight hundred and forty-seven health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries.

Participants

Key informants from 847 health research institutions.

Main outcome measures

The availability, mix and quality of human resources in health research institutions.

Results

On average, there were 122 females employed per respondent health research institution, compared with 159 males. For researchers, the equivalent figures were nine females to 17 males. The average annual gross salary of researchers varied between US$ 12,260 for staff with 5–10 years of experience and US$ 14,772 for the institution head. Of those researchers who had joined the institution in the previous 12 months, 55% were employed on a full-time basis. Of the researchers who left the institutions in the same period, 71% had a full-time contract. Among all those who left, those who left to a non-research sector and to another country accounted for two-thirds.

Conclusions

The study revealed significant gaps in the area of human capacity development for research in Africa. The results showed a serious shortage of qualified staff engaged in health research, with a dearth of staff that held at least a master’s degree or doctoral degree. Major efforts will be required to strengthen human resource capacity, including addressing the lack of motivation or time for research on the part of existing capable staff.

Keywords: human resource for research, health research workforce, health research in Africa, health research institutions

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa has a high burden of disease, estimated to be five times higher than that of established market economies.1 Also well known and documented is the fact that health systems in African countries are weak and increasingly unable to sustain their response to this enormous disease burden.2 Factors that have contributed to weakening the health system include but are not limited to the following: weak institutional and human resource capacities, the ‘brain-drain’ phenomenon, lack of incentives, inefficient use of potential national expertise and inadequate research capacity.3

The failure adequately to address pertinent health challenges for which cost-effective solutions are available has been attributed in part to the under-investment in research capacity and development in sub-Saharan Africa. Research capacity comprises the institutional and regulatory frameworks, infrastructure, investment and sufficiently skilled people to conduct and publish research findings.4 Equally important is the ability to translate research into action through sharing results with national and subnational stakeholders. Most African countries have been categorised as ‘lagging behind’ in research, and these inequalities in health research have been said to contribute to inequalities in health.5 There is a growing demand from national and international development partners that efforts and research priorities be made according to importance of health issues, and in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, the emphasis has shifted to health systems research, human capacity development and research capacity strengthening.

Scientific publications play a key role in providing a linkage between knowledge production and use. According to scientific publication activity worldwide, most countries in Africa have continued to have low levels of publication over the past decade, despite increased levels of scientific research.6 A World Health Organization (WHO) report7 shows that, of all scientific publications addressing health topics from different regions of the world, only 1% were from Africa. In an analysis of all scientific research in Africa published in journals indexed by PubMed® between 1996 and 2005,6 it was found that 60% of all publications from the African continent were from Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa. An increasing trend in the number of publications from Nigeria and South Africa was noted, along with reductions in numbers from the Gambia and Zimbabwe. Africa’s low contribution to global scientific research publication may be attributed to low research and development expenditure, poor research methods owing to lack of skills and problems of research presentation such as writing style and language competency.

According to Bates et al.,8 the process required for building capacity in health research would be to define the institutional systems needed to support research, enumerate existing and missing resources and improve research support by addressing the identified gaps. This report presents a synthesis and profile of human capacity and staff movement in national health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries. The purpose of the surveys was to provide estimates for benchmarks of national health research systems as a means to describe, monitor and analyse national health research activities and improve national research capacities, as well as to share experiences across low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

The methods followed to assess national health information systems are described elsewhere9 but are described briefly here.

The main criterion for considering an institution as a ‘health research institution’ was that it should be engaged in the conception or creation of new knowledge, products, processes, methods and systems related to any aspect of health, such as factors affecting health and ways of promoting and improving it. Institutions could be departments of medical schools, universities, teaching or non-teaching hospitals, independent research institutions, governmental agencies, pharmaceutical and other for-profit and not-for-profit businesses, charities and non-governmental organisations.

The survey used Tool 6 from the Health Research System Analysis (HRSA) Initiative: Methods for Collecting Benchmarks and Systems Analysis Toolkit.10 Within the institutional survey, seven questionnaires (representing separate modules) were completed by the respondent institutions. This report draws on data from two of those questionnaires:

Module 1000 – Identification, introduction and background information

Module 5000 – Human resource for research

These questionnaires are designed to focus on issues pertaining to the human resources available for research at the institutional level.

For response to questions where institutions were asked to rank items in the questionnaire, we used weighting schemes to arrive at composite ranks. For example, where the response required ranking an item on a 1–5 scale, a weight of five was given to the first rank, four to the second rank and so on, with the fifth rank getting the least weight of one. The average of these was used to derive a composite rank of items.

We used IBM® SPSS® Statistics Version 19 statistical software to analyse the data.

Results

The institution survey dataset included responses from up to 847 institutions in 42 countries in the WHO African Region (all except Algeria, Angola, Sierra Leone and South Africa). Half of the respondent institutions were aged under 30 years; 70.3% belonged to the public sector; 12.5% were independent research institutions and 64.3% functioned at the national level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

| Characteristics | Health research institutions |

|

|---|---|---|

| No.* | % | |

| Age of institution (years) (n = 694) | ||

| <30 | 426 | 61 |

| 30–59 | 200 | 29 |

| ≥60 | 68 | 10 |

| Sector the institution belong to (n = 762) | ||

| Public | 536 | 70 |

| Private not-for-profit | 132 | 17 |

| Para-state | 37 | 5 |

| Private for-profit | 26 | 3 |

| Other | 31 | 4 |

| Type of institution (n = 847) | ||

| Government agencies | 257 | 30 |

| Hospitals | 154 | 18 |

| Medical schools | 108 | 13 |

| Independent research institutions | 106 | 13 |

| Other research institutions (non-governmental organisations, charities) | 105 | 12 |

| Other universities | 95 | 11 |

| Other | 22 | 3 |

| Level at which institution functions (n = 751) | ||

| National | 483 | 64 |

| Local | 140 | 19 |

| Regional | 60 | 8 |

| International | 55 | 7 |

| Other | 13 | 2 |

| Primary functions of institution (n = 697) | ||

| Conduct research on health topics | 374 | 54 |

| Academic | 373 | 54 |

| Provide health services | 338 | 48 |

| Conduct research on non-health topics | 122 | 18 |

| Product development or distribution | 74 | 11 |

| Other | 128 | 18 |

| National official or working language (n = 847) | ||

| French | 445 | 53 |

| English | 285 | 34 |

| Other | 117 | 14 |

| Institution has mandate on | ||

| Research of all types | 571 | 79 (n = 723) |

| Health research | 563 | 77 (n = 731) |

*Number of respondent health institutions, out of 847 surveyed.

A comparison of men and women involved in all research and in health research revealed that on average there were 122 women employed per respondent institution, compared with 159 men. For researchers, the equivalent figures were nine women per institution to 17 men (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sex and age distribution of researchers and employees at health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

| Details of employees | Institutions | Individuals | Mean | 95% confidence interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Current employees (all types) who are | |||||

| Male, full-time | 599 | 95,344 | 159.2 | 89.5 | 228.9 |

| Male, part-time | 422 | 14,858 | 35.2 | 18.2 | 52.2 |

| Female, full-time | 580 | 71,191 | 122.7 | 59.9 | 185.5 |

| Female, part-time | 397 | 3631 | 9.1 | 5.7 | 12.5 |

| Sex of health researchers | |||||

| Male | 457 | 7650 | 16.7 | 10.5 | 23.0 |

| Female | 413 | 3804 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 14.0 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20–29 | 254 | 1967 | 7.7 | 0.7 | 16.2 |

| 30–39 | 350 | 3168 | 9.1 | 5.6 | 12.5 |

| 40–49 | 350 | 3716 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 10.5 |

| 50–59 | 301 | 2067 | 6.9 | 2.9 | 10.8 |

| ≥60 | 396 | 425 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

Analysis of human capacity in research institutions looked at researchers and technical staff in the countries surveyed. The two categories of staff have been defined as ‘professional’. Researchers accounted for about one-third of all staff of institutions, with a mean of 34 researchers per respondent institution. Overall, among all the institution surveyed, the number of national researchers averaged 17 per respondent institution more than non-national researchers (6 per institution). The average annual gross salary of researchers varied between US$ 12,260 for staff with 5–10 years of experience and US$ 14,772 for the head of the institution (Table 3).

Table 3.

Types of employees and contractual arrangements for health researchers in 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

| Details of employees | Institutions | Individuals | Mean | 95% Confidence interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Types of employees | |||||

| Researchers | 550 | 18,610 | 33.8 | 24.0 | 43.7 |

| Technicians | 524 | 20,367 | 38.9 | 29.2 | 48.6 |

| Other supporting staff | 535 | 27,980 | 52.3 | 36.9 | 67.7 |

| Part-time | 327 | 5199 | 15.9 | 5.9 | 25.9 |

| Full-time | 340 | 4238 | 12.5 | 6.8 | 18.2 |

| Type of contracts | |||||

| Short term/non-tenure track | 238 | 754 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 5.1 |

| Fixed term/tenure | 236 | 764 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| Average annual gross wage (US$) | |||||

| Newly graduated PhD, <5 years’ experience | 222 | – | 13,034 | 8388 | 17,679 |

| Researcher with 5–10 years’ experience | 188 | – | 12,260 | 8446 | 16,073 |

| Researcher with 10–20 years’ experience | 228 | – | 14,458 | 9669 | 19,248 |

| Director or head of the institution | 199 | – | 14,772 | 9994 | 19,549 |

Information pertaining to research capacity in terms of the qualifications of health researchers was also derived. Health researchers were categorised into five groups:

Bachelor’s degree (BA, BS, 3–4 years of post-secondary education)

Master’s degree (MS, MA, MPH, MBA or equivalent)

Professional doctorate degree (MD, medical; DDS, dental; JD, law)

Research doctorate (PhD, DPhil, ScD, DrPH or equivalent)

Both professional and research doctorate (MD/PhD; MD/JD)

On average, there were 4.6 research doctorate degree holders per respondent institution, accounting for 23% of all health researchers. With regard to staff reported to be involved in health research who hold a master’s degree, the average per institution was 5.1, although they accounted for about one-third of all health researchers (Table 4).

Table 4.

Academic credentials of researchers in health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

| Details of employees | Institutions | Researchers | Mean | 95% confidence interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Academic credentials of researchers | |||||

| Professional doctorate degree | 293 | 2543 | 8.7 | 5.9 | 11.4 |

| Bachelor degree | 310 | 2477 | 8.0 | 5.2 | 10.8 |

| Master’s degree | 346 | 2737 | 7.9 | 5.4 | 10.4 |

| Research doctorate degree | 279 | 1206 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 5.7 |

| Professional and research doctorate degree | 234 | 876 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 6.8 |

| Academic credentials of health researchers | |||||

| Professional doctorate degree | 302 | 2271 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 10.1 |

| Bachelor degree | 306 | 1945 | 6.4 | 4.4 | 8.3 |

| Master’s degree | 334 | 1703 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 6.5 |

| Research doctorate degree | 279 | 1280 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 9.5 |

| Professional and research doctorate degree | 228 | 519 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 4.7 |

Of those researchers who had joined the institutions in the 12 months prior to the survey, 55% were employed on a full-time basis. Likewise, of the researchers who had left the institutions in the same period, 71% had a full-time contract. Among all those who had left, those who left to a non-research sector and to another country accounted for two-thirds (Table 5).

Table 5.

Staff movement in to and out of health research institutions in 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

| Details of employees | Institutions | Researchers | Mean | 95% confidence interval |

% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Number of health researchers who joined the institution in the past 12 months | ||||||

| Working part-time | 176 | 609 | 3.46 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 27 |

| Working full-time | 212 | 1237 | 5.83 | 3.3 | 8.4 | 55 |

| Have short term/non-tenure track contract | 150 | 193 | 1.29 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 9 |

| Have fixed term/tenure contract | 153 | 229 | 1.50 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 10 |

| Number of health researchers who left the institution in the past 12 months | ||||||

| Working full-time | 181 | 271 | 1.50 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 71 |

| Have short term/non-tenure track contract | 132 | 44 | 0.33 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 11 |

| Have fixed term/tenure contract | 139 | 69 | 0.50 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 18 |

| Number of health researchers who left the institution for the following reasons | ||||||

| To work in another institution doing health research activities in the country | 165 | 75 | 0.45 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 37 |

| To work in a different sector in the country (i.e. not health research) | 152 | 70 | 0.46 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 34 |

| To work in another country | 147 | 59 | 0.40 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 29 |

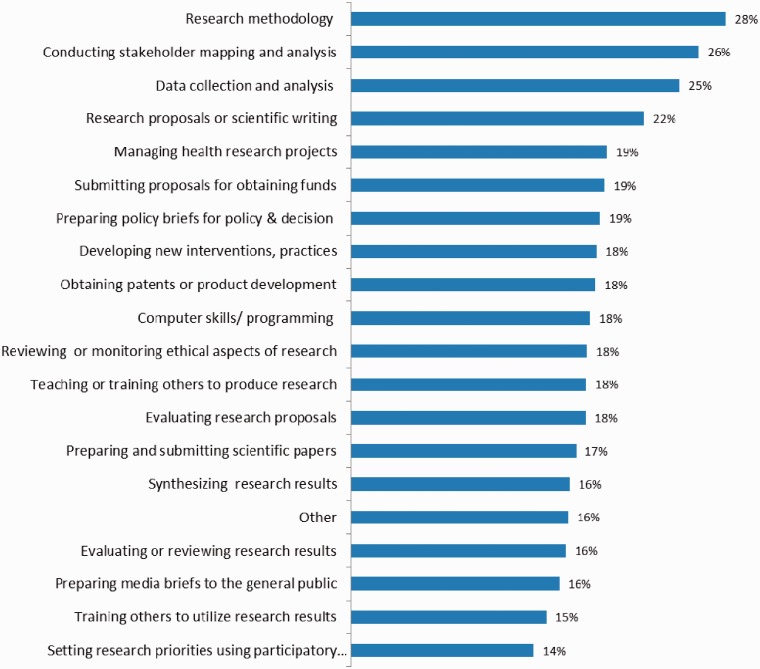

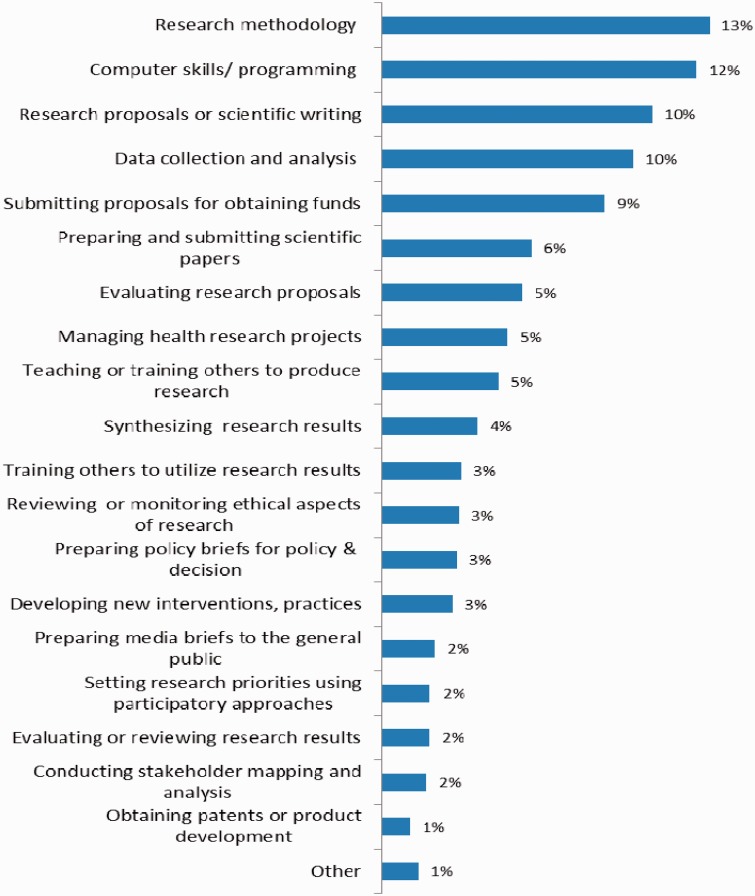

Respondent institutions answered the question of which top five competencies the institution looked for in the recruitment and selection of new research staff. The most considered factors were translating questions into research hypotheses/research methodology (28%), conducting stakeholder mapping and analysis (26%), developing/utilising appropriate qualitative or quantitative data collection and analysis approaches (25%), preparation of research proposals or scientific writing (22%) and managing health research projects (22%) (Figure 1). They were also asked which top five competencies needed to be strengthened in their institutions. Research methodology (cited by 13% of respondent institutions), computer skills (12%) and proposal and scientific writing (10.5%); data collection and analysis (9.8%) and submitting proposals for obtaining funds (9%) topped the priority list (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Competencies used by health research institutions for recruitment and selection of new research staff, 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

Figure 2.

Competencies perceived as important by health research institutions for strengthening the capacity of research staff, 42 sub-Saharan African countries, 2009.

Inquiries were made regarding the basis for the institution to promote researchers working on health topics. The most cited criteria for promotion were:

Number of research proposals submitted

Number of research proposals approved

Scientific merit of research proposal

Relevance of research proposal to research priorities

Number of publications submitted

Number of articles published in peer-reviewed journals

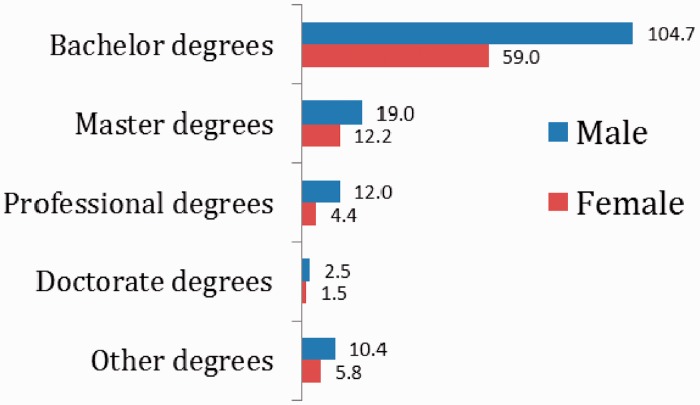

To assess the level of output of institutions for graduates trained in research and therefore having the potential to do health research, respondents were asked to state for their institutions how many degrees were granted in the previous academic year at bachelor, master’s and doctorate levels for nationals. The average number of bachelor degrees granted per respondent institution was 105 for men and 59 for women, and the average number of doctorate degrees was 2.5 for men and 1.5 for women (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average number of degrees granted to nationals per year by health research institutions by sex in 42 sub-Saharan African Region, 2009.

Discussion

The results show a serious shortage of qualified staff engaged in health research in these countries. Ideally, qualified health researchers would hold at least a master’s degree, as undergraduate degrees alone do not normally equip staff sufficiently to conduct research. The survey shows that these percentages are low for master’s degrees and much lower for doctoral degrees.

In Africa, as elsewhere in the world, much of the research is conducted in academic settings. However, according to available published findings, most African countries with severe human resources for health shortages have only one to three health professional training institutions.11 Even then, the number of health workers produced from these institutions each year and the quality of education they receive is mostly unknown. In one survey conducted by the Joint Learning Initiative, it was found that the capacity to produce health staff was limited in general, with some countries lacking either a medical school or nursing school.2 This was especially so in countries with critically low numbers of human resources.

It was encouraging to note that the majority of staff in health research institutions were full-time staff. However, some of these full-time staff were also reported to have left in the previous 12 months. Many institutions in sub-Saharan Africa find it hard to attract, recruit and retain qualified full-time staff, due in part to funding constraints. It is a vicious cycle, as without qualified staff these institutions find it difficult, if not impossible, to compete for international research grants, with most of these grants going to institutions in developed countries. These institutions then cannot generate significant levels of funding with which to attract or retain skilled staff, who may then go on to be employed in institutions in developed countries.

According to Tettey’s12 survey of five training institutions in five countries, academic staff are usually required to divide their time between teaching, research, research supervision and administration, with research getting less time. The same survey also revealed that most institutions were small and relied heavily on part-time staff. When only numbers of full-time staff were considered, over 80% of units delivering postgraduate public health education had 20 staff members or less, while over 60% had less than 10 staff members.13 In such situations, it is not surprising that researchers tend to dedicate even less time to research, both in terms of participating and publishing. If science is to meet its goal of improving health and spurring development, all countries should be able to participate in research.4

Another major finding is the serious sex imbalance, with women under-represented among health researchers. The level of imbalance between men and women among health researchers in both full-time and part-time employment is expected due to the traditional male dominance in professional employment in Africa and elsewhere globally. One survey12 covering 13 countries with 72 institutions revealed that there were 854 staff members working in these institutions, 58% of whom were full-time staff, an average of 12 staff members per institution. In all institutions, there was a tendency for more male than female staff. The majority (66%) of staff were between 36 and 50 years while 15% were below 35 years and 19% were above 50 years. It would appear that strategies to increase human capacity for health research must make efforts to address this imbalance by bringing more women into health research work.

Training of health personnel to master’s degree and doctoral levels usually includes significant amounts of research training and experience. However, the shortage of these cadres suggests that overall capacity to conduct quality research is quite limited in most countries. Only a small number of institutions reported having produced any master’s or doctoral degree graduates. Without the requisite investment by governments and their partners to improve local production of staff at these levels, it would be difficult for these countries to have any significant numbers and to acquire the capacity that is needed to conduct meaningful research and development to address the problems faced by their countries.

There is a clear shortage of people trained at doctoral level engaged in any research. Those institutions that are older may have more doctorate level and medical and master’s degree holders engaged in health research than other institutions, as they have had more time to develop their own graduate-level training programmes and reduce dependence on expatriate staff for health research.

Access to skill-development opportunities and career mobility are very important for health professionals. Institutions that are under-staffed have to weigh filling available posts against sending their staff for further training. African universities continue to contend with a shortage of academic staff and do not seem capable of mobilising the intellectual strength needed to drive capacity-building efforts. Our findings are similar to those of other surveys13 that indicate a shortage of senior staff, which could be due to migration, illness or internal transfer to better-funded positions among others. The shortage of senior staff also signals the absence of sufficient numbers of mentors for upcoming academic professionals.

Our results also show that it was mostly full-time staff who were reported to have left their institutions in the previous 12 months. This is a pointer to the inadequate capacity of these institutions to motivate and retain tenured staff. This is probably because in recent years there has been a significant increase in funding for health programmes, especially brought about by the global health initiatives such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the U.S. President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief; the President’s Malaria Initiative; the GAVI Alliance and other bilateral initiatives. These findings are in agreement with the literature review suggestions that young academics often find it more rewarding to work outside academic institutions.11 Although in absolute terms the numbers of staff who left to go to outside countries may look small, it does add to the severe shortage of skilled staff given the numbers are small to begin with. Moreover, it takes much longer for these staff who left in the year to be replaced with similarly skilled or experienced personnel.

Training institutions seem to have difficulty recruiting and retaining staff. In addition to the difficulty in attracting sufficiently trained professionals with postgraduate qualifications, inadequate pay, poor working conditions and unattractive terms of service are some of the reasons for low staffing levels in these institutions.12 While salaries are important, staff in academia would also appreciate getting other benefit packages in terms of good health coverage, car and housing loan schemes, support for children’s education and a reasonable pension, but most of these benefits are limited or are not available in African training institution.12 A survey of five African universities reported a small number of students opting to pursue graduate education, partly due to the lack of resources for maintaining significant research-based programmes, unattractiveness of academic jobs and unappealing salaries. Younger academics were found to be more likely to depart from academic settings, lured by the possibility of the potential for promotion elsewhere. For more senior staff approaching retirement, concerns about their inadequate retirement package prompt them to depart from academia to pursue external, better-paying jobs. For example, at the University of Ghana, a 2006 survey revealed that 10 staff members at the rank of senior lecturer had resigned over the previous three years to take up positions with local and international organisations outside of academia.12

Our analysis and report is one of the few studies that focuses on human capacity for health research and staff movements within African national health research systems. However, the study has some limitations. The datasets showed that many of the variables were returned as missing, suggesting to us that the data were not collected or were simply unavailable and that the data we have represent the best efforts of the in-country staff and their contacts or sources. The aim was to obtain a complete census of all health research institutions across the Region. However, as a complete census was not obtained, it is difficult to determine the representativeness of the results using statistical tools on the data gathered. The data described in this report are not representative, in a statistical sense, of what could be happening in some countries. The data only record research output and use at the institutions surveyed by this questionnaire.

Conclusions

The study reveals significant gaps in the areas of human capacity development for research in Africa. This reflects both the lack of capacity in the countries and the lack of motivation or time for research on the part of existing capable staff. African countries provide the clearest example of health systems under stress. Given the severe shortage of healthcare resources, concrete plans to strengthen health systems should focus on the following key areas: the potential for human resources development, capacity for health-related research and use of information for decision-making. Therefore, in Africa’s human resource constrained settings, it is not surprising that research outputs continue to be low. Overall, there is insufficient research on human capacity, mentoring and development for research in Africa to provide information to policy-makers regarding countries facing the greatest challenges and to identify areas that are immediately in need of strengthening.

This report serves to fill part of the gap and to highlight some areas for future studies. Furthermore, as there is scant literature on human capacity and training for research, and on staff movement in African national health research systems, this is an area for future research.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

WHO Regional Office for Africa

Ethical approval

Not required because the survey did not touch on ethical issues requiring individual consent.

Guarantor

DK

Contributorship

DK wrote the paper and carried out the statistical analyses, CK, PEM, IS and WK reviewed the paper and assisted with fieldwork, PSLD reviewed the initial design of the study and provided support and overall leadership.

Acknowledgements

WHO Country Office focal persons for information, research and knowledge management are acknowledged for their contribution in coordinating the surveys in countries. Their counterparts in ministries of health are also acknowledged. These surveys would not have been possible without the active participation of the head of health research institutions and their department heads who have given their time and effort to fill out and send back the completed modules and questionnaires. The contribution of the consultant who prepared the background material for this paper is also acknowledged.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Jennifer Hall

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care Now More Than Ever, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Evans T, Anand S. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. The Lancet 2004; 364: 1984–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Agency for International Development. The Health Sector Human Resource Crisis in Africa: An Issues Paper, Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development, Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volmink J. Addressing inequalities in research capacity in Africa (editorial). BMJ 2005; 331: 705–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaakidis P, Swingler GH, Pienaar E, Volmink J, Ioannidis JP. Relation between burden of disease and randomized evidence in sub-Saharan Africa: survey of research. BMJ 2002; 324: 702–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uthman OA, Uthman MB. Geography of Africa biomedical publications: an analysis of 1996–2005 PubMed papers. Int J Health Geogr 2007; 6: 46–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. World Report on Knowledge for Better Health: Strengthening Health Systems, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates I, Akoto AYO, Ansong D, et al. Evaluating health research capacity building: an evidence-based tool. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e299–e299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kebede D, Zielinski C, Mbondji PE, Sanou I, Kouvividila W, Lusamba-Dikassa P-S. Surveying the knowledge landscape in sub-Saharan Africa: methodology. J R Soc Med 2014; 107(suppl. 1): 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadana R, Lee-Martin SP, Racelis R, Lee J, Berridge S. Health Research System Analysis (HRSA) Initiative: Methods for Collecting Benchmarks and Systems Analysis Toolkit. Tool #6. Survey of Institutions Contributing to Health Research, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tettey WJ. Academic staff attrition at African universities. International Higher Education 2006; 44: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.IJsselmuiden CB, Nchinda TC, Duale S, Tumwesigye NM, Serwadda D. Mapping Africa’s advanced public health education capacity: the AfriHealth project. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 901–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]