Abstract

Objective

Associations between olfactory function to quality-of-life (QOL) and disease severity in patients with rhinosinusitis is poorly understood. We sought to evaluate and compare olfactory function between subgroups of patients with rhinosinusitis using the Brief Smell Identification Test (BSIT).

Study Design

Cross-sectional evaluation of a multi-center cohort.

Methods

Patients with recurrent acute sinusitis (RARS) and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) with and without nasal polyposis were prospectively enrolled from three academic tertiary care sites. Each subject completed the BSIT, in addition to measures of disease-specific QOL. Patient demographics, comorbidities, and clinical measures of disease severity were compared between patients with normal (BSIT; ≥9) and abnormal (BSIT; <9) olfaction scores. Regression modeling was used to identify potential risk factors associated with olfactory impairment.

Results

Patients with rhinosinusitis (n=445) were found to suffer olfactory dysfunction as measured by the BSIT (28.3%). Subgroups of rhinosinusitis differed in the degree of olfactory dysfunction reported. Worse disease severity, measured by computed tomography and nasal endoscopy, correlated to worse olfaction. Olfactory scores did not consistently correlate with Rhinosinusitis Disability Index or Sinonasal Outcome Test scores. Regression models demonstrated nasal polyposis was the strongest predictor of olfactory dysfunction. Recalcitrant disease and aspirin intolerance were strongly predictive of worse olfactory function.

Conclusion

Olfactory dysfunction is a complex, multi-factorial process found to be differentially expressed within subgroups of rhinosinusitis. Olfaction was associated with disease severity as measured by imaging and endoscopy, with only weak associations to disease-specific QOL measures.

MeSH Key Words: Olfaction disorders, sinusitis, quality of life, inflammation, smell

INTRODUCTION

Impaired olfaction is commonly observed in patients with sinonasal disease with a prevalence reported up to 30–60% of this patient population1,2 and is a criterion used for the diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).3 Despite the high prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in patients with CRS and its link to QOL and disease severity, olfaction is understudied within the larger population as defined by rhinosinusitis.

Olfactory dysfunction in rhinosinusitis is likely multi-factorial, due to both a conductive and an uncontrolled inflammatory component that contributes to sensorineural damage of the olfactory neuroepithelium.4,5 Therefore, one would predict that olfactory dysfunction would be differentially expressed between patient subgroups of rhinosinusitis allowing us to differentiate significant inflammatory and structural cofactors that are associated with abnormal olfactory scores.

The goals of this study were to evaluate olfaction in a multi-institutional cohort of patients utilizing a validated instrument of olfaction assessment, systematically compare olfactory function between subgroups of patients with rhinosinusitis: a) CRS with nasal polypsosis (CRSwNP), b) CRS without NP (CRSsNP), c) recurrent acute sinusitis (RARS), and to identify significant risk factors associated with olfactory impairment.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study Population

Adult patients (≥18 years) with sinonasal disease were enrolled into a prospective, observational cohort investigation within three, academic, tertiary rhinology practices: Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, OR.), the Medical University of South Carolina (Charleston, SC.), and Stanford University (Palo Alto, CA.). All research study subjects underwent comprehensive clinical evaluation consisting of physical evaluations, computed tomography (CT) imaging, and bilateral, rigid sinonasal endoscopy examinations as part of the normal standard of care.

Study inclusion criteria consisted of a diagnosis of recurrent acute rhinosinusitis (RARS) or CRS as defined by the 2007 Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Adult Sinusitis Guidelines.3 Study subjects with RARS were defined as four or more episodes per year of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis without signs or symptoms of rhinosinusitis between episodes. Diagnosis of CRS is defined by persistent symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks. Patient with CRS had undergone previous treatment with oral antibiotics (≥2 weeks duration) and either topical nasal corticosteroid sprays (≥3 week duration) or a 5-day trial of systemic steroid therapy. Patients were required to complete all necessary enrollment study questionnaires and sign informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at each study site monitored and approved all investigational protocols.

Study participants reported demographic, social, and medical history data including: age, gender, race, ethnicity, education level, depression, and ciliary dysfunction, recalcitrant disease (failed medical and surgical management) / history of prior sinus surgery, asthma, allergy (confirmed skin prick or radioallergosorbent testing), acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) intolerance, current tobacco use, and history of depression. A history of RARS, CRS with polyposis (CRSwNP), CRS without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP), septal deviation, and inferior turbinate hypertrophy were assessed during the history and physical exam. Because olfactory dysfunction is most likely multi-factorial stemming from a combination of both physical/structural and inflammatory components comorbid and clinical characteristics were further grouped into physical/structural factors and inflammatory factors. Patients were screened and excluded if they had a diagnosis of disease processes known to be associated with olfactory dysfunction including: Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, or multiple sclerosis.

Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT)

Olfactory function was evaluated and measured during the initial enrollment period using The Brief Smell Identification Test.6 The B-SIT, is a validated 12-item, standardized, non-invasive quantitative test of olfactory function, that employs 12 microencapsulated odorant strips in a “scratch ‘n sniff” format activated with a standard #2 pencil (score range: 0–12). Higher scores indicate better olfactory function while lower scores represent olfactory dysfunction. Both male and female respondents can be classified as having “normal” (B-SIT ≥ 9) or “abnormal” (B-SIT < 9) olfaction. Normal and abnormal olfactory function was determined in each subject based on young male and female adult norms.

Clinical Disease Severity Measures

Computed tomography images were evaluated and staged in accordance with the Lund-Mackay bilateral scoring system (total score range: 0–24) where higher scores represent higher severity of disease as indicated by image opacification in sinonasal regions.7 Endoscopic examinations were scored using the Lund-Kennedy endoscopy staging system (total score range: 0–20) where higher scores represent worse disease severity.8

Disease-Specific Quality of Life Measures

Study participants also completed two CRS-specific QOL instruments; the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index (RSDI) and the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22), which are both validated to characterize CRS-specific disease burden. The RSDI (total score range: 0–120) is a 30-item, disease-specific survey instrument consisting of three subscales that evaluate the impact of CRS on a patient’s physical (score range: 0–44), functional (score range: 0–36), and emotional (score range: 0–40) status. Higher reported scores on the RSDI indicate greater disease-specific impacts on QOL and daily function.9 The SNOT-22 is a validated, treatment outcome measure applicable to chronic sinonasal conditions (total score range: 0–110).10 Lower total scores on the SNOT-22 suggest better QOL and lower symptom severity. The enrolling physicians at each site were blinded to all survey responses for the study duration.

Statistical Analysis

All clinical and survey data was collected, transferred, and manually entered into a central, relational database (Microsoft Office Access 2007; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) by the study coordinator utilizing standardized clinical research forms. Statistical associations were performed using a commercially obtainable statistical software package (IBM SPSS Statistics v.21.0; IBM Corp. New York, NY). Graphical analysis was utilized to evaluate normality and linearity assumptions and descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, and ranges) were calculated for all patient demographics, disease severity and QOL measures. Two-tailed, independent sample t-tests, Mann Whitney U tests, and chi-square (χ2) testing was used to assess bivariate differences between patients with and without normal B-SIT scores where appropriate. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate differences in mean B-SIT scores between patient subgroups with RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP, while adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni test. F-test statistics, degrees of freedom (df), and corresponding t-test statistics were reported where appropriate. Two-tailed Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rs) were used to assess nonparametric correlations between B-SIT scores, disease severity measures, and QOL measures.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent patient characteristics associated with abnormal B-SIT scores (dependent variable) while providing adjusted effect estimates, evidence of collinearity, and identification of effect modification. Two separate models were constructed to identify: 1) structural/anatomical characteristics, and 2) inflammation-related characteristics associated with abnormal olfaction scores. Variables for both models were built using a standard forward selection (p=0.010) and backwards elimination (p=0.050) technique in a manual stepwise process. Finals models were assessed for goodness-of-fit using standard Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 test statistics.11 Crude and adjusted effect estimates (β), odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported with corresponding p-values.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

A total of 445 patients were enrolled between March, 2011–May, 2013 and completed the B-SIT and all required study materials. All completed B-SIT scores were dichotomized into “normal” and “abnormal” as described above and evaluated across patient characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics dichotomized by normal and abnormal olfactory B-SIT scores

| Characteristics: | Normal B-SIT scores (n=319) | Abnormal B-SIT scores (n=126) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | 47.6 (14.8) | 53.8 (14.8) | <0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Males | 144 (45.1) | 67 (53.2) | |||

|

| |||||

| Females | 175 (54.9) | 59 (46.8) | 0.126 | ||

|

| |||||

| Race: | |||||

|

| |||||

| White/Caucasian | 270 (84.6) | 106 (84.1) | |||

|

| |||||

| African American | 22 (6.9) | 8 (6.3) | |||

|

| |||||

| Asian | 14 (4.4) | 4 (3.2) | |||

|

| |||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (0.9) | --- | |||

|

| |||||

| “Other” | 10 (3.1) | 8 (6.3) | 0.425 | ||

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity: | |||||

|

| |||||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 309 (96.9) | 120 (95.2) | |||

|

| |||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (3.1) | 6 (4.8) | 0.406 | ||

|

| |||||

| Education level (years) | 15.2 (2.9) | 14.8 (2.8) | 0.179 | ||

|

| |||||

| Depression (history/self report) | 55 (17.2) | 20 (15.9) | 0.728 | ||

|

| |||||

| Ciliary dysfunction | 16 (5.1) | 4 (3.2) | 0.398 | ||

|

| |||||

| Physical / structural factors: | |||||

|

| |||||

| Septal deviation | 131 (41.1) | 29 (23.0) | <0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Recurrent acute rhinosinusitis | 30 (9.4) | 3 (2.4) | 0.011 | ||

|

| |||||

| Inferior turbinate hypertrophy | 64 (20.1) | 16 (12.7) | 0.068 | ||

|

| |||||

| Inflammatory factors: | |||||

|

| |||||

| Nasal polyposis** | 73 (22.9) | 79 (62.7) | <0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Recalcitrant Disease | 149 (46.7) | 88 (69.8) | <0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Asthma | 92 (28.8) | 61 (48.4) | <0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| ASA intolerance | 12 (3.8) | 21 (16.7) | <0.001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Allergies by testing# | 111 (34.8) | 53 (42.1) | 0.152 | ||

|

| |||||

| Steroid dependency: | |||||

|

| |||||

| Asthma | 11 (3.4) | 6 (4.8) | 0.515 | ||

|

| |||||

| Sinusitis | 6 (1.9) | 4 (3.2) | 0.407 | ||

|

| |||||

| Current tobacco smoker | 16 (5.0) | 9 (7.1) | 0.380 | ||

inflammatory and structural factor.

confirmed via skin prick or mRAST testing.

B-SIT, Brief Smell Identification Test. SD, standard deviation.

Those with normal olfaction were more likely to have septal deviation and RARS. Inferior turbinate hypertrophy was more frequent in patients with normal olfaction however this trend was not statistically significant. Patients with abnormal olfactory function were found to be slightly older and have a higher prevalence of nasal polyposis, recalcitrant disease / history of prior sinus surgery, asthma, and ASA intolerance.

Olfactory Function

All study subjects (n=445) had a mean B-SIT score of 9.1(3.1). Subjects with normal B-SIT scores (n=319; 71.7%) had mean B-SIT scores of 10.8(1.0) compared to a mean of 4.7(2.2) for all subjects with abnormal olfaction (n=126; 28.3%).

Without separating for normal or abnormal olfactory status, subjects with RARS (n=33) and CRSsNP (n=260) were found to have significantly higher mean B-SIT scores (10.5(1.4) and 9.9(2.2), respectively) compared to the CRSwNP subgroup (7.3(3.8); F= 46.208; df=2; p<0.001).

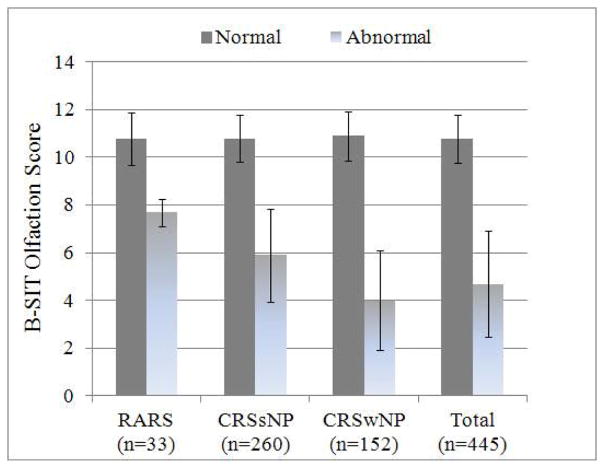

Between subgroups with normal olfaction, there were no significant differences found in mean BSIT scores (F= 0.279; df=2; p=0.757). Significant differences were found however between RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP subgroups with abnormal olfaction (F= 15.031; df=2, p<0.001). Patients with RARS had significantly higher abnormal mean B-SIT scores when compared to subjects with CRSwNP (7.7(0.6) vs. 4.0(2.1); t= 3.051; df=80; p=0.009). Likewise, subjects with CRSsNP were found to have significantly higher mean abnormal BSIT scores (5.8(2.0)) compared to subject with CRSwNP (t= −4.809; df=121; p<0.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Average normal and abnormal B-SIT olfaction scores for study subjects with RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP. Error bars represented ±1.0 standard deviation from the mean.

The prevalence of normal olfaction was higher in both subjects with RARS and CRSsNP (90.9% and 83.1%, respectively) compared to subjects with CRSwNP (48.0%; p≤0.009).

Olfaction and Disease Severity Measures

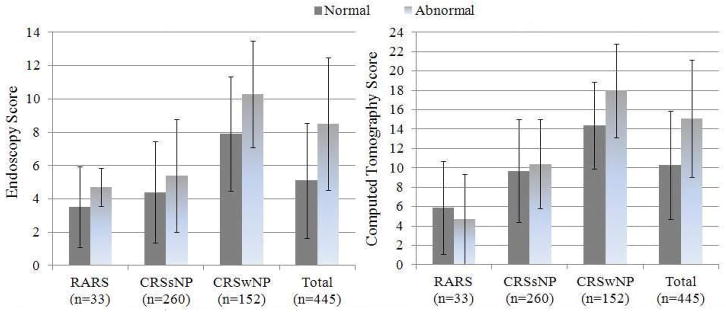

All patients (n=445) were found to have an average endoscopy score of 6.1(3.9), range between 0 – 20, and average CT score of 11.7(6.1), range between 0 – 24. Patients with normal olfaction had significantly lower average endoscopy scores and lower average CT scores compared to subjects with abnormal olfaction (5.1(3.4) vs. 8.5(4.0); p<0.001) and (10.3(5.6) vs. 15.1(6.1); p<0.001) respectively. Disease severity measures across normal and abnormal olfaction, between RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP subgroups, are further described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of normal and abnormal B-SIT scores to disease severity measures across RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP subgroups.

| Disease severity measures: | Normal B-SIT Scores (n=319) | Abnormal B-SIT Scores (n=126) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | [Range] | Mean (SD) | [Range] | ||

|

| |||||

| RARS | |||||

|

| |||||

| B-SIT Olfactory score | 10.8 (1.1) | [9 – 12] | 7.7 (0.6) | [7 – 8] | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Endoscopy score | 3.5 (2.4) | [0 – 10] | 4.7 (1.2) | [4 – 6] | 0.260 |

|

| |||||

| CT score | 5.9 (4.8) | [0 – 14] | 4.7 (4.6) | [2 – 10] | 0.883 |

|

| |||||

| CRSsNP | |||||

|

| |||||

| B-SIT Olfactory score | 10.8 (1.0) | [9 – 12] | 5.9 (1.9) | [2 – 8] | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Endoscopy score | 4.4 (3.1) | [0 – 14] | 5.4 (3.3) | [0 – 16] | 0.044 |

|

| |||||

| CT score | 9.7 (5.3) | [0 – 24] | 10.4 (4.8) | [1 – 20] | 0.371 |

|

| |||||

| CRSwNP | |||||

|

| |||||

| B-SIT Olfactory score | 10.9 (1.0) | [9 - 12] | 4.0 (2.1) | [0 – 8] | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Endoscopy score | 7.9 (3.4) | [0 – 17] | 10.3 (3.2) | [4 – 20] | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| CT score | 14.4 (4.5) | [4 – 24] | 18.0 (4.8) | [5 – 24] | <0.001 |

B-SIT, Brief Smell Identification Test. SD, standard deviation. RARS, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis. CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis. CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis.

Patients with normal olfaction within the subgroups of RARS and CRSsNP were found to have significantly better endoscopy scores (F=39.314; df=2; p<0.001) and CT scores (F=34.288; df=2; p<0.001) compared to subjects with CRSwNP (Table 2). Patients with normal olfaction and RARS had significantly better CT scores (t=−3.702; df=239; p<0.001) compared to subjects with CRSsNP.

For patients with abnormal olfaction, subjects with RARS were found to have lower mean endoscopy scores (F=32.664; df=2, p<0.001) and CT scores (F=38.404; df=2; p<0.001) compared to patients with CRSsNP and CRSwNP. Subjects with abnormal olfaction and CRSsNP were found to have significantly lower mean endoscopy scores (t=7.764; df=121; p<0.001) and CT scores (t=7.872; df=114; p<0.001) compared to patients with abnormal olfaction and CRSwNP.

Significant differences in both average endoscopy and average CT scores, between subgroups with RARS, CRSsNP, or CRSwNP, were found for patients with and without normal olfaction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average endoscopy and computed tomography scores using the Lund-Kennedy and Lund-Mackay staging systems across normal and abnormal olfactory status for subjects with RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP. Error bars represented ±1.0 standard deviation from the mean.

Correlations Between Olfaction and Disease Severity

Significant inverse correlation coefficients were found between B-SIT scores and both endoscopy scores and CT scores for the total cohort and the subgroup of subjects with CRSwNP (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between B-SIT scores and disease severity scores for subjects with RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP

| Disease severity measures: | RARS rs |

CRSsNP rs |

CRSwNP rs |

Total rs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopy score | −0.247 | −0.123** | −0.370* | −0.341* |

| CT score | 0.126 | −0.111 | −0.403* | −0.318* |

B-SIT, Brief Smell Identification Test. RARS, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis. CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis. CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. CT, computed tomography.

indicates a p-value <0.001.

indicates a p-value < 0.05.

Olfaction and Quality of Life Measures

Comparisons of the QOL survey scores from the total cohort (n=445) found no significant differences between patients with normal and abnormal B-SIT scores on the SNOT-22 or RSDI total scores (Table 4). Similar comparisons of subjects within the RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP subgroups found no significant differences in normal and abnormal olfaction on SNOT-22 or RSDI total scores.

Table 4.

Bivariate analysis comparing normal and abnormal B-SIT scores to disease-specific QOL scores in patients with RARS, CRSsNP, and CRSwNP

| Disease-specific QOL measures: | Normal B-SIT scores (n=319) | Abnormal B-SIT scores (n=126) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RARS: | Mean (SD) | [Range] | Mean (SD) | [Range] | p-value |

| SNOT-22 | 51.2 (18.8) | [18 – 85] | 75.0 (33.2) | [38 – 102] | 0.168 |

| RSDI Total | 48.2 (23.8) | [5 – 104] | 74.7 (38.1) | [35 – 111] | 0.235 |

| CRSsNP: | Mean (SD) | [Range] | Mean (SD) | [Range] | p-value |

| SNOT-22 | 50.9 (18.6) | [4 – 106] | 55.5 (22.8) | [6 – 102] | 0.210 |

| RSDI Total | 44.7 (24.9) | [1 – 107] | 52.1 (29.4) | [4 – 114] | 0.148 |

| CRSwNP: | Mean (SD) | [Range] | Mean (SD) | [Range] | p-value |

| SNOT-22 | 48.4 (22.8) | [4 – 106] | 53.1 (18.5) | [0 – 94] | 0.104 |

| RSDI Total | 40.5 (25.0) | [1 – 116] | 43.7 (21.2) | [7 – 89] | 0.268 |

| Total cohort: | Mean (SD) | [Range] | Mean (SD) | [Range] | p-value |

| SNOT-22 | 50.4 (19.6) | [4 – 106] | 54.0 (20.1) | [0 – 102] | 0.083 |

| RSDI Total | 44.1 (24.8) | [1 – 116] | 46.8 (24.8) | [4 – 114] | 0.291 |

B-SIT, Brief Smell Identification Test. RARS, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis. CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis. CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. QOL, quality of life. SD, standard deviation. SNOT-22, 22-Item Sinonasal Outcome Test. RSDI, Rhinosinusitis Disability Index.

Correlation Coefficients Between Olfaction and Quality of Life Measures

No significant correlations were found between continuous B-SIT olfactory scores and continuous measures of disease-specific QOL for the total cohort, RARS, and CRSsNP. However, when broken down into subgroup classifications of disease status, inverse correlations were found between the B-SIT and QOL as measured by the SNOT-22 and the emotional domain of the RSDI in patients with CRSwNP (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients between B-SIT scores and disease-specific QOL scores for subjects with RARS, CRSwNP, and CRSsNP.

| Disease-specific QOL measures: | Total (n=445) rs |

CRSsNP (n=291) rs |

CRSwNP (n=152) rs |

RARS (n=34) rs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 | −0.078 | −0.030 | −0.192** | −0.187 |

| RSDI physical | −0.076 | −0.078 | −0.145 | −0.207 |

| RSDI functional | −0.028 | −0.048 | −0.091 | −0.096 |

| RSDI emotional | −0.076 | −0.064 | −0.168** | −0.222 |

| RSDI total | −0.062 | −0.061 | −0.138 | −0.157 |

QOL, quality of life. CRSsNP, chronic rhinosinusisits without nasal polyps. CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. RARS, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis. SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. RSDI, Rhinosinusitis Disability Index.

indicates a p-value <0.001.

indicates a p-value < 0.05.

Physical / Structural Modeling Variables of Olfactory Dysfunction

Final model selection found that septal deviation (OR=1.679; 95% CI: 1.004, 2.808) was a significant predictor of better olfactory function (p=0.048; Table 6). Within the structural model, nasal polyposis was found to be the strongest predictor of worse olfactory function. A concurrent diagnosis of RARS was not associated with olfactory function (OR=1.594; 95% CI: 0.436, 5.830; p=0.481) and subsequently dropped from final models. Likewise, unilateral or bilateral inferior turbinate hypertrophy was not significantly associated with abnormal olfactory scores (OR=0.656; 95% CI: 0.326, 1.318; p=0.236) after controlling for all other factors. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test statistic (χ2=4.483; df=8, p=0.811) indicated adequate final model fit while no evidence of significant collinearity or effect modification was found.

Table 6.

Final logistic regression model with significant structural and inflammatory cofactors associated with abnormal B-SIT olfactory scores

| Cofactors: | β | Adjusted β | OR | 95% CI [LB, UB] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural factor model: | |||||

| Age | 0.028 | 0.027 | 0.974 | [0.958, 0.989] | 0.001 |

| Gender (males) | −0.322 | −0.088 | 1.092 | [0.689, 1.728] | 0.709 |

| Septal deviation | −0.846 | −0.518 | 1.679 | [1.004, 2.808] | 0.048 |

| Nasal polyposis | 1.734 | 1.692 | 0.184 | [0.116, 0.292] | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory factor model: | |||||

| Age | 0.028 | 0.028 | 1.029 | [1.012, 1.045] | 0.001 |

| Gender (males) | −0.322 | −0.136 | 0.873 | [0.547, 1.394] | 0.570 |

| Nasal polyposis | 1.734 | 1.497 | 4.467 | [2.768, 7.206] | <0.001 |

| Recalcitrant disease | 0.972 | 0.614 | 1.847 | [1.138, 3.000] | 0.013 |

| ASA intolerance | 1.633 | 1.102 | 3.011 | [1.314, 6.897] | 0.009 |

β, beta effect estimate. S.E., standard error. OR, odds ratio. CI, confidence interval. LB, lower bound. UB, upper bound. ASA, acetylsalicyclic acid. Nasal polyposis was evaluated as both a structural and inflammatory variable while both models were adjusted for age and gender (male reference group).

Inflammatory Modeling Factors of Olfactory Dysfunction

Age and gender adjusted final models for independent variables associated with sinonasal inflammation found that concurrent allergy was not significantly associated with abnormal olfactory function (OR=0.743; 95% CI: 0.458, 1.204; p=0.227; Table 6) and subsequently fell out of final model selection. Similar to structural modeling outcomes, nasal polyposis was strongly associated with worse olfactory function. Recalcitrant disease with a history of prior sinus surgery and ASA intolerance were also significantly associated with worse olfactory function. Goodness-of-fit test statistics again indicated marginal final model fit (χ2=8.663, df=8, p=0.372) and no evidence of significant collinearity or effect modification were noted.

DISCUSSION

This large cross-sectional study comparatively examines clinical characteristics associated with olfactory dysfunction using an objective measure of olfaction across subgroups of rhinosinusitis. This study demonstrates that olfaction is differentially affected between patients within subgroups of rhinosinusitis, which coincides with previous investigations that have demonstrated that patients with CRS have olfactory disabilities.12 Disease severity as measured by CT and endoscopy was associated with olfactory dysfunction in the subgroups of rhinosinusitis but did not correlate to disease-specific QOL. Logistical regression models were developed to systematically evaluate independent variables associated with both inflammatory and structural abnormalities and found that nasal polyposis, recalcitrant disease, and ASA sensitivity significantly contributed to olfactory impairment. Age and gender were adjusted for in the B-SIT scoring system and did not require further adjustment as independent variables in the model.

Olfaction is an important neurosensory function that has become increasingly investigated due to its ability to modulate behavior and cognition, influence QOL, and to assess disease severity in multiple pathologic conditions ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to CRS.13 The neurobiology of olfaction involves activation of complex intracellular signaling cascades triggered by specific, odorant compounds. Olfactory input travels to second order neurons with highly characterized connections to the limbic system and higher cortical regions essential for cognitive functioning. This implies that olfactory function influences input-output signaling in higher cortical centers that may subsequently influence behavior and QOL in CRS. It is unknown if the local inflammatory milieu measured in the sinonasal mucosa correlates to olfactory dysfunction in CRS.

Severe inflammation as seen on CT and endoscopy is most likely contributing to not only a conductive component of olfactory dysfunction, but also to sensorineural olfactory dysfunction. Disease severity as measured by CT and nasal endoscopy was found to be significantly associated with olfactory dysfunction such that the objective measures of olfaction correlated with CT and endoscopy scores (p<0.001; Table 3). However, this significance was lost when the cohort was broken down into subgroups of rhinosinusitis, as olfaction did not correlate to disease severity in RARS, while CRSsNP was weakly associated to endoscopy scores but not to CT scores. Previous studies have demonstrated that disease severity as measured by CT is correlated to olfactory dysfunction in CRS,14 with olfactory cleft opacification being the most important indicator.15 As expected, our results are in agreement; disease severity, evident by CT and endoscopy, predicts greater olfactory impairment.

Intuitively one would predict that olfactory dysfunction would be a predictor of rhinosinusitis disease-specific QOL as prior studies suggest that olfaction plays a role in impairing QOL4. However, we demonstrate that rhinosinusitis disease-specific QOL measures such as the SNOT-22 and RSDI have limited capability to detect olfactory dysfunction as measured by the B-SIT. This is in accordance with earlier investigations, which were unable to demonstrate any correlations between olfactory impairment and CRS disease-specific QOL as measured by the RSDI and CSS.14 This is not completely unexpected, as the CSS does not contain any specific olfaction items while the RSDI contains a single olfaction item. Furthermore, when olfactory specific questions were removed from the SNOT-22 (question #21 “Sense of smell/taste”) and RSDI (question #7 “Food does not taste good because of my change in smell”) the mild significance we found was lost (all p ≥0.239). Overall, while the SNOT-22 and RSDI may have had some capacity to measure the impact of olfactory dysfunction as it relates to QOL, we found these instruments to be limited in their sensitivity to evaluate patients’ olfactory discrimination. Investigations undertaken to evaluate associations between olfaction and rhinosinusitis-specific QOL should be explored with specific validated patient-based, olfactory specific outcomes measures.13

Those patients with structural abnormalities such as septal deviation and RARS were more likely to be normosmic while those patients historically thought to have more of an inflammatory disease such as those with asthma, ASA intolerance, and CRSwNP had worse olfactory dysfunction. The degree of nasal obstruction as it relates to olfaction in CRS is still under investigation as there is conflicting data regarding improving olfaction following surgery that addresses structural defects. Such that nasal obstruction is not predicative of olfactory improvement following nasal septal surgery in patients with CRS.16,17 In contrast, patients with nasal obstruction without rhinosinusitis have no improvement in olfaction following surgery.18 We acknowledge that patients with nasal polyps can be considered to represent both structural and inflammatory components. As such, patients with CRSwNP who undergo polypectomy demonstrate improvement in anosmia at both 6 and 12 months, while those with hyposomia showed no improvement following surgery.19 Likewise, others have shown olfactory dysfunction in patients with CRSwNP with conflicting outcomes in olfactory improvement following surgery.20,21 In addition, it is strikingly evident that even within the nasal polyposis group, a large proportion of these patients (48%) have normal olfactory scores. This evidence as a whole, suggests that olfaction in sinonasal disease is most likely multifactorial consisting of both conductive and sensorineural components.

The strengths of this study include its multi-institutional prospective design to report olfactory impairment collected from a large cohort of patients with rhinosinusitis using the B-SIT. The B-SIT has several important advantages over other odorant instruments. For instance: 1) it has been validated as an objective measure of olfactory discrimination, 2) it has cross-cultural use, 3) it can be easily mailed to study participants for self-administration, 4) it requires minimal questionnaire time burden (5 minutes) with ease of administration in a busy clinical setting, and 5) the B-SIT correlates to the more commonly used and more burdensome UPSIT instrument in patients with CRS.22,23 The primary disadvantage of the B-SIT has to do with its limited ability to differentiate levels of olfactory dysfunction and less sensitivity among those patients with sinonasal disease. However, it has been used to characterize olfactory function in a variety of other diseases and has been used to validate other forms of olfactory function measurements.24,25 In addition, odor identification is commonly used in large-scale epidemiological studies and we demonstrate that the B-SIT can be a tangible option in measuring olfactory dysfunction and identifying risk factors in rhinosinusitis.

CONCLUSION

Patients with sinonasal disease differ in their severity of olfactory dysfunction as measured by the BSIT instrument. Poor olfaction was significantly associated with disease severity as measured by CT and endoscopy scores, although, it was not pervasive among all subgroups of rhinosinusitis. Olfactory dysfunction did not correlate as well to rhinosinusitis-specific QOL measures. Future studies are needed to further elucidate the etiology and pathophysiology of olfactory dysfunction in sinonasal disease.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None

Level of Evidence: 2b

Financial Disclosures: Jess C. Mace, MPH, and Timothy L. Smith, MD, MPH are supported by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), one of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. (R01 DC005805; PI/PD: TL Smith). Public clinical trial registration (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) ID# NCT01332136. Timothy L. Smith, MD is also a consultant for IntersectENT (Menlo Park, CA) which is not affiliated with this investigation.

References

- 1.Litvack JR, Fong K, Mace J, James KE, Smith TL. Predictors of olfactory dysfunction in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:2225–2230. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318184e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raviv JR, Kern RC. Chronic sinusitis and olfactory dysfunction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37:1143–1157. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007;137:S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katotomichelakis M, Simopoulos E, Tripsianis G, et al. Improvement of olfactory function for quality of life recovery. Laryngoscope. 2013 doi: 10.1002/lary.24113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane AP, Turner J, May L, Reed R. A genetic model of chronic rhinosinusitis-associated olfactory inflammation reveals reversible functional impairment and dramatic neuroepithelial reorganization. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2324–2329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4507-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doty R. The Brief Smell Identification Test adminstration manual. Haddon Height (NJ): Sensonics Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitus. Rhinology. 1993;31:183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benninger MS, Senior BA. The development of the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1997;123:1175–1179. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900110025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clinical Otolaryngology. 2009;34:447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doty RL, Mishra A. Olfaction and its alteration by nasal obstruction, rhinitis, and rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:409–423. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simopoulos E, Katotomichelakis M, Gouveris H, Tripsianis G, Livaditis M, Danielides V. Olfaction-associated quality of life in chronic rhinosinusitis: adaptation and validation of an olfaction-specific questionnaire. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1450–1454. doi: 10.1002/lary.23349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litvack JR, Mace JC, Smith TL. Olfactory function and disease severity in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:139–144. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DW, Kim JY, Jeon SY. The status of the olfactory cleft may predict postoperative olfactory function in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:e90–94. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang RS, Su MC, Liang KL, et al. Preoperative prognostic factors for olfactory change after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:64–70. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schriever VA, Gupta N, Pade J, Szewczynska M, Hummel T. Olfactory function following nasal surgery: a 1-year follow-up. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies. 2013;270:107–111. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-1972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damm M, Eckel HE, Jungehulsing M, Hummel T. Olfactory changes at threshold and suprathreshold levels following septoplasty with partial inferior turbinectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:91–97. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litvack JR, Mace J, Smith TL. Does olfactory function improve after endoscopic sinus surgery? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pade J, Hummel T. Olfactory function following nasal surgery. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1260–1264. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318170b5cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang RS, Lu FJ, Liang KL, et al. Olfactory function in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis before and after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:445–448. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugiyama K, Hasegawa Y, Sugiyama N, Suzuki M, Watanabe N, Murakami S. Smoking-induced olfactory dysfunction in chronic sinusitis and assessment of brief University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test and T&T methods. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:439–444. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item Cross-Cultural Smell Identification Test (CC-SIT) Laryngoscope. 1996;106:353–356. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller C, Renner B. A new procedure for the short screening of olfactory function using five items from the “Sniffin’ Sticks” identification test kit. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krantz EM, Schubert CR, Dalton DS, et al. Test-retest reliability of the San Diego Odor Identification Test and comparison with the brief smell identification test. Chem Senses. 2009;34:435–440. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjp018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]