Abstract

The current study examined interactions among genetic influences and children’s early environments on the development of externalizing behaviors from 18 months to 6 years of age. Participants included 233 families linked through adoption (birth parents and adoptive families). Genetic influences were assessed by birth parent temperamental regulation. Early environments included both family (overreactive parenting) and out-of-home factors (center-based Early Care and Education; ECE). Overreactive parenting predicted more child externalizing behaviors. Attending center-based ECE was associated with increasing externalizing behaviors only for children with genetic liability for dysregulation. Additionally, children who were at risk for externalizing behaviors due to both genetic variability and exposure to center-based ECE were more sensitive to the effects of overreactive parenting on externalizing behavior than other children.

Keywords: externalizing behavior, early care and education, genetics, parenting, genotype × environment interaction

Externalizing behaviors that emerge during the early childhood years, including hyperactivity, inattention, aggressive, and oppositional behaviors, are associated with difficulties in both academic and social domains (e.g., Bulotsky-Shearer & Fantuzzo, 2011; Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Fantuzzo & McWayne, 2002; Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999; McWayne & Cheung, 2009). Children who exhibit more externalizing behaviors in preschool or elementary school tend to face challenges in establishing positive relationships with their peers and teachers at school (Bulotsky-Shearer, Domínguez, Bell, Rouse, Fantuzzo, 2010; Justice, Cottone, Mashburn, & Rimm-Kaufman, 2008; Ladd et al., 1999; Whittaker & Harden, 2010), as well as with family members (e.g., Larsson, Viding, Rijsdijk, & Plomin, 2008). Children with early externalizing behaviors also tend to show less motivation, persistence, and positive attitudes toward learning in preschool, which are in turn linked with lower achievement in elementary school (e.g., McWayne & Cheung, 2009). Understanding the factors that contribute to externalizing behaviors during early childhood is therefore of great importance, and may have meaningful implications for prevention.

Early childhood has been shown to be a key time in development for the emergence of externalizing behaviors; individual differences that emerge during early childhood often persist throughout childhood and adolescence (e.g., Reef, Diamantopoulou, van Meurs, Verhulst, & van der Ende, 2011; Sanson, Hempill, & Smart, 2004; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). Exposure to negative, harsh, or overreactive parenting is associated with increased externalizing behavior during early childhood (e.g., Calkins, 2002; Rothbaum &Weisz, 1994; Shaw et al., 2003; Tremblay et al., 2004). Experiences outside the home also play a role in the development of externalizing behavior. Although Early Care and Education (ECE) programs are associated with gains in cognitive and academic skills they are also linked with increasing externalizing behavior (Loeb, Bridges, Bassok, Fuller, & Rumberger, 2007; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network [NICHD ECCRN], 2002, 2004; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). Effects of ECE on externalizing behaviors tend to be smaller than effects of parenting, and have not been linked with clinical ranges of externalizing behaviors. Additionally, individual differences in externalizing behaviors are, in part, genetically influenced (Burt, 2009; Rhee & Waldman, 2002), and influenced by genotype × environment interactions (GxE) during childhood and adolescence (Feinberg, Button, Neiderhiser, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2007; Leve et al., 2009; Lipscomb et al., 2012).

To date, studies of GxE during early childhood have primarily focused on children’s proximal factors in the home, most notably parenting. The current study expands upon this work by examining how genetic influences may moderate the effects of contextual factors on externalizing behaviors within out-of-home settings (exposure to center-based ECE) in addition to the home environment (overreactive parenting) during early childhood. Simultaneously accounting for parenting and ECE when predicting children’s externalizing behavior is important because these factors commonly covary (NICHD ECCRN, 2004). By using longitudinal data from a sample of adoptive parents, adopted children, and birth parents, genetic and environmental contributions and GxE can be examined, without contamination by the effects of genes shared among genetically-related family members (i.e., elimination of passive genotype × environment correlation effects, Rutter Pickles, Murray, & Eaves, 2001).

Genetic Influences as a Moderator of Environmental Effects

Several different frameworks can be used to conceptualize GxE interaction (e.g., Reiss, 2012; Rutter, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2006; Rutter & Silberg, 2002). The current study uses an adoption study to examine genetic influences as a marker of children’s sensitivity to potential environmental stressors within the framework of a Diathesis-Stress perspective (Reiss, Leve & Neiderhiser, in press). Diathesis-Stress models propose that children inherit sensitivity to stressors in their environments and that it is in the face of these stressors that the problems are manifested (Zuckerman, 1999). Unlike molecular genetic studies, in which the effects of specific gene variants are examined in relation to specific outcomes, the parent-offspring adoption design considers the expressed effects of the whole genome by measuring associations between birth parents and the adopted child. Because the birth parents are not rearing the child, associations between birth parent characteristics and adopted child characteristics are necessarily due to either genetic or prenatal influences (for birth mothers) and cannot be due to postnatal environmental influences. When accounting for prenatal influences (as in the current study), associations between birth parents and the adopted child can be inferred to reflect the phenotypic expression of the whole genome. There is a need to examine genetic influences using multiple approaches, including behavioral genetic and molecular genetic strategies, as this helps to provide a more complete picture of how genes and environments work together to influence child development and to better capture to possible mechanisms of effect (Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2012). The parent-offspring adoption design has been particularly useful for detecting gene-environment interplay in the present sample and other adoption studies (Cadoret et al., 1996; Leve et al., 2009; O’Connor, Deater-Deckard, Fulker, Rutter, & Plomin, 1998; O’Connor, Caspi, DeFries, & Plomin, 2003).

Birth parent temperamental regulation (a combination of low self-control and negative emotionality) was selected as the indicator of genetic risk for this analysis because it has been shown to be heritable (Gagne, Saudino, & Asherson, 2011; Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Saudino, 2005), with heritability estimates for self-control during early childhood ranging from 39 to 73% (Gagne et al. 2011). Temperamental self-regulation is also associated with externalizing behaviors (Gagne et al., 2011; Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Vitaro, Barker, Boivin, Brendgen, & Tremblay, 2006). When considered together, low self-control and high negative emotionality represent a temperamental system indicative of dysregulation in both children and adults (Digman, 1997; Evans & Rothbart, 2009; Markon et al., 2005; Rothbart, Sheese, Rueda, & Posner, 2011). We examine birth parent low self-regulation (a combination of high negative emotionality and low self-control) as an indicator of genetic liability for dysregulation that may make it more difficult for children to maintain regulation in the context of overreactive parenting and center-based ECE, as manifested by elevated levels of externalizing behaviors.

Center-Based Early Care and Education (ECE)

Children’s ECE experiences play a significant role in their development across a wide variety of areas relevant to school readiness, including behavior and early academics (Belsky et al. 2007; Magnuson & Waldfogel, 2005; NICHD ECCRN, 2005). Center-based ECE appears to help young children prepare for success in school by contributing to more positive early academic and cognitive skills, but evidence also points to center-based care increasing externalizing behaviors, even when controlling for the quality and quantity of care children receive (Haskins, 1985; NICHD ECCRN, 2002, 2004; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). Compared to children who are cared for at home, or in family child care settings, children who attend center-based care typically experience large peer groups and heightened social interaction and competition (Fabes, Harnish, & Martin, 2003), which can be stressful for some young children (e.g., Donzella, Gunnar, Krueger, & Alwin, 2000). Effects of these early experiences in center-based ECE on externalizing behaviors are modest; ECE has not been linked to clinical ranges of externalizing behaviors. However, if a large percentage of young children experience these effects, due to high enrollment in center-based ECE in order to promote early academic skills (more than half of all four year olds in the United States attend center-based ECE; U.S. Department of Education, 2011a), even modest effects on behavior have great societal importance. A recent study suggests that children’s child care histories can influence the overall social dynamics of their kindergarten classrooms, affecting their peers’ behavioral development as well as their own (Dmitrieva, Steinberg, & Belsky, 2007). Considering the increasing national emphasis on early education in the United States (U.S. Department of Education, 2011b) it is imperative that we better understand the effects of ECE on behavioral development.

The small overall effects of center-based ECE on externalizing behaviors for young children as a whole, which have been consistently documented in the United States, may indicate that only some children respond to center-based ECE with increasing externalizing behavior, and/or that certain children are more sensitive than others to these effects. Some evidence indicates stronger effects of ECE experiences for children from disadvantaged backgrounds (e.g., Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001). However, socioeconomic status is not likely to explain all of the heterogeneity in effects of ECE.

An emerging line of research explores whether children whose underlying biological systems are especially reactive may be the ones most strongly influenced by their experiences in ECE (Belsky & Pluess, 2013; Phillips, Fox, & Gunnar, 2011; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). This type of biological sensitivity may be important in understanding children’s development in a variety of domains. It may have particular relevance for understanding the link between exposure to center-based ECE and externalizing behaviors in young children because this link likely involves children’s responsiveness to environmental stressors (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2005), which has a biological basis (e.g., Gillespie, Phifer, Bradley, & Ressler, 2009). Indeed, long hours of center-based ECE are associated with elevated cortisol levels (Watamura, Donzella, Alwin, & Gunnar, 2003), especially for subgroups of children, such as those who tend to display more externalizing behavior (Dettling et al., 1999; Tout et al., 1998).

Researchers have only begun to examine the possibility that children’s biological background moderates their sensitivity to ECE in predicting externalizing behavior. To date most of this work has focused on temperament as a marker of biological sensitivity (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2005; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). More recently, Belsky and Pluess (2013) examined interactions between two specific genetic polymorphisms (DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR) and children’s ECE experiences on social and behavioral outcomes. Findings pointed to a moderating role of DRD4 in the effect of ECE quality on children’s externalizing problems that was consistent with a Diathesis-Stress perspective. No evidence of genetic moderation of the effect of center-based ECE on externalizing was detected. The current study builds from this emerging line of work by using an adoption study design which permits genetic and postnatal environmental influences to be disentangled. Specifically, birth parent low self-regulation is examined as a moderator of the association between exposure to center-based ECE and children’s development of externalizing behaviors, accounting for the number of hours children spend in ECE settings and other child and family characteristics.

Overreactive Parenting and GxE

Children’s genetic backgrounds may also moderate the effects of their experiences within the family on their development of externalizing behaviors. Overreactive, negative, or harsh parenting has been consistently linked with negative outcomes such as externalizing behaviors during childhood and adolescence (e.g., Calkins, 2002; Maccoby, 2000; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Shaw et al., 2003; Tremblay et al., 2004), including in a recent study with the current sample (Lipscomb et al., 2012). These associations are often conceptualized as a coercive cycle in which harsh parenting practices and child behavioral problems reinforce one another (e.g., Larsson, et al., 2008; Patterson & Fisher, 2002; Scaramella, Neppl, Ontai, & Conger, 2008; Shaw et al., 1998).

Indeed, evidence suggests that interplay between children’s genes and their experiences are important to understanding the development of externalizing behaviors during childhood and adolescence (e.g., Button, Scourfield, Martin, Purcell, & McGuffin, 2005; Hicks, South, Dirago, Iacono, McGue, 2009; Feinberg et al., 2007; Leve et al., 2009; Lipscomb, et al., 2012). However, very little research has examined how children’s genes may moderate their sensitivity to harsh or overreactive parenting during early childhood. Molecular genetic studies provide some initial evidence, suggesting that children who inherit the long allele of the DRD4 gene show heightened sensitivity to effects of insensitive parenting on their externalizing behaviors during preschool (Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van IJzendoorn, 2006; DiLalla, Elam, & Smolen, 2009). The current study builds on this finding, using an adoption design. A prior analysis with the current sample indicates that adoption designs may be fruitful in examining genetic influences as a moderator of parenting on young children’s externalizing behaviors (Leve et al., 2009). Leve and colleagues (2009) found that genetic influences moderated the effect of structured parenting on toddlers’ behavioral problems at 18-months of age.

The current study examines the role of genetic influences as a marker of sensitivity to both children’s experiences with overreactive parenting and with out-of-home center-based ECE. We include overreactive parenting as a time-varying predictor of children’s development of externalizing behaviors, such that parenting and child behavior are linked concurrently across time. This approach allows for examination of the effect of genetic variability on the degree of association between parenting and child behavior, recognizing that the behavior of both parents and children may change over time. With this approach, we also account for parenting when estimating effects of ECE on children’s emerging externalizing behaviors. This is important because of selection effects, as family characteristics commonly covary with children’s ECE arrangements (NICHD ECCRN, 2004).

In addition to two-way GxE interactions (birth parent self-regulation × center-based ECE; birth parent self-regulation × overreactive parenting), the current study also explores the possibility of a 3-way interaction (GxExE) in which genetic variability (birth parent self-regulation) and attending center-based ECE jointly affect children’s sensitivity to overreactive parenting. Conceptually, this is an extension of the Diathesis-Stress model (which suggests dual-risks) to a triple-risk model. Consider a child with a genetic background that is primed for emotional reactivity and poor self-regulation who attends center-based ECE and then returns home to overreactive parents. Center-based ECE may stress this child’s already vulnerable self-regulatory system such that he or she is more sensitive to his/her parents’ overreactive behaviors than other children are to their similarly overreactive parents because of differences in genetic and ECE factors, thereby accentuating the link between overreactive parenting and child externalizing behaviors.

The Present Study

This study uses an adoption design where the rearing parent does not share genes with the child, thereby allowing for a separation of genetic and environmental influences. In this study we examine genetic variability (birth parent self-regulation) as a moderator of the effects of both family (overreactive parenting) and out-of-home (exposure to center-based ECE) environments on children’s development of externalizing behaviors from 18 months to 6 years of age. As discussed earlier, this is an important developmental period during which individual differences in externalizing behaviors emerge and begin to predict social and academic difficulties. Main effects of overreactive parenting and center-based ECE are also examined. In addition, we explore a 3-way interaction in which genetic influences and exposure to center-based child care increase the effect of overreactive parenting on children’s externalizing behaviors.

It was hypothesized that (1) children whose birth parents had poor regulation would be more sensitive than other children to the effects of center-based ECE on increases in externalizing behaviors over time, (2) children with birth parents who had poor regulation would be more sensitive than other children to the effect of overreactive parenting on externalizing behaviors, and (3) the combination of having birth parent with poor regulation and exposure to center-based ECE would amplify the magnitude of the association between overreactive parenting and externalizing behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from Cohort I of the Early Growth and Development Study, a longitudinal study of adopted children and their birth and adoptive parents. Recruitment of Cohort I participants occurred between 2003 and 2006, beginning with the recruitment of adoption agencies (N = 33 agencies in 10 states located in the Northwest, Mid-Atlantic, and Southwest regions of the United States). The participating agencies reflected the full range of adoption agencies operating in the United States: public, private, religious, secular, those favoring open adoptions, and those favoring closed adoptions. Agency staff identified participants who completed an adoption plan through their agency and met the following eligibility criteria: (a) the adoption placement was domestic, (b) the infant was placed within 3 months postpartum (M = 7.11 days postpartum, SD = 13.28; median = 2 days), (c) the infant was placed with a nonrelative adoptive family, (d) birth and adoptive parents were able to read or understand English at the eighth-grade level, and (e) the infant had no known major medical conditions such as extreme prematurity or extensive medical surgeries. Of the families who met eligibility criteria, 68% (n = 361) agreed to participate. The participants were representative of the adoptive parent population that completed adoption plans at the participating agencies during the same time period (Leve et al., 2013).

The sample included male (57%) and female (43%) children with a range of racial backgrounds (57.6% White, 11.1% Black/African American, 9.4% Latino, 20.8% multiracial, .3% American Indian/Alaskan Native, .6% unknown or not reported). Adoptive parents were predominantly White (over 90% of adoptive mothers/fathers) and middle class and involved in a stable marital or marriage-like relationship (M = 18.5 years, SD = 5.2 at first assessment). The current analyses are based on the subset (n = 233) of the total sample for which birth parent regulation and child ECE data were available. See Analytic Strategy section (below) for additional information on missing data and comparison of cases included vs. not included in the current sample.

Procedure and Measures

Parent and child data for this study were collected through in-person interviews, home-based questionnaires, and web-based assessments. Data were collected when the child was 9 months, 18 months, 27 months, 4.5 years, and 6 years old. Additional details on each measure and timing of assessments are given below.

Birth parent self-regulation

The Adult Temperament Questionnaire-Short Form (ATQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, 2000) was administered to birth parents at the 18-month assessment. The ATQ is a self-report measure of adult temperament that was adapted from the Physiological Reactions Questionnaire developed by Derryberry and Rothbart (1988). The 77 items are used to calculate 13 subscales. The 7 subscales collectively comprise negative affect (frustration, sadness, discomfort, and fear; all reversed scored) and effortful control (activation control, attention control, and inhibitory control); subscales were combined into an overall measure of genetic risk for dysregulation. This is consistent with work by Evans and Rothbart (2009) in which all 7 subscales loaded on a common factor representing high effortful control and low negative affect. If both birth parents’ data were available (n = 77 out of the 233 families for whom child ECE data were also available), their regulation scores were averaged because this represented the most comprehensive measure of birth parent self-regulation. Otherwise, the birth mother’s score (n = 156) was used to represent regulation (r = .93 between birth mother only and cross-parent average scores). Preliminary analyses suggested that only using birth mother scores (versus using combined scores) yielded very similar results. Internal consistency for the composite score was acceptable (α = .77).

Overreactive parenting

Adoptive parent self-reported overreactivity was measured at all occasions from 18 months to 6 years of age by the 10-item overreactivity subscale of the Parenting Scale (Arnold, O’Leary, Wolf, & Acker, 1993). The scale was designed to identify parental discipline mistakes that relate theoretically to externalizing behaviors, with higher scores indicating more overreactivity. Each identified mistake was paired with its more effective counterpart to form the anchors for a 7-point scale (e.g., when I’m upset or under stress...1= I am no more picky than usual; 7 = I am picky and on my child’s back. When my child misbehaves…1= I speak to my child calmly; 7 = I raise my voice or yell). Scores from adoptive mothers (AM) and fathers (AF) were combined for each occasion in order to obtain an overall measure of children’s exposure to overreactive parenting (with an average correlation of r = .24 across parents, p < .01). Inter-item alphas were acceptable (average AM α = .76; average AF α = .73).

Early care and education (ECE)

When children were 4.5 years old, adoptive mothers were asked a series of questions about children’s prior and current ECE experiences, including the type of ECE (if any), amount of time spent in ECE arrangements, and age the child first entered this type of ECE arrangement. The primary variable of interest for this study was whether or not the child had ever attended center-based ECE on a regular basis for at least 10 hours per week (0 = “no”; 1 = “yes”), which is the cut-off used in prior research (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007). Age of entry into group-based ECE, and the amount of time children spent in their current ECE arrangements were considered as potential covariates. Children with any ECE experience had entered center-based ECE on average at 26 months (SD = 15.6 months, range 1 – 57 months), and they attended their current ECE arrangements for an average of 20.6 hours per week (SD = 12.6; range 4 – 50).

Externalizing behaviors

Child externalizing behaviors were measured at each occasion from 18 months to 6 years of age using the 24-item, broadband Externalizing factor from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). The CBCL consists of 99 behaviors rated on a 3-point scale with values of 0 (not true), 1 (sometimes true), and 2 (very true). The Externalizing factor is comprised of all items from the narrow-band Aggression and Attention subscales (AM α = .87; AF α = .90) and was selected over specific narrow-band factors in the present analyses because we were concerned with children’s development of externalizing behaviors at a general level, rather than specific components such as aggression, oppositionality, or ADHD symptoms. An average of mother- and father-reported T-scores at each occasion was computed for use in the analysis (average r = .44, p < .01 across parent reports) in order to obtain an overall measure of children’s externalizing behaviors.

Analytic Strategy

We utilized multilevel modeling with HLM (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to test our hypotheses. This approach separates variance into within-child (i.e., repeated measures of externalizing behaviors and experiences of parental overreactivity; Level 1) and between-child factors (i.e., center-based ECE and birth parent regulation; Level 2). HLM allows missing data at Level 1 while using Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation to arrive at model parameters. Missing data are not allowed at Level 2, which necessitated the deletion of cases with incomplete ECE and/or birth parent regulation information. A comparison of cases included vs. not included revealed that the former tended to have birth parents with better self-regulation, t(264) = −2.22, p < .05, and the child was more likely to be in center-based ECE, χ2(1) = 31.12, p < .001. Families with missing versus complete data did not differ on any other demographic or study variables, including child externalizing behaviors.

Child externalizing behaviors from 18 months to 6 years were modeled at Level 1 with an intercept (β0) and linear slope (β1). The intercept was centered at the final assessment, representing the child’s predicted level of externalizing behaviors at 6 years, and the slope represented growth in externalizing behaviors from 18 months to 6 years. Parental overreactivity was added at Level 1 as a time-varying covariate (β2) centered at the mean of repeated measures for each child, representing the association between child externalizing and parental overreactivity trajectories over time.

At Level 2, center-based ECE, birth parent regulation, and center-based ECE × birth parent regulation variables were added as predictors of the intercept and slope of externalizing behaviors as well as the effect of parental overreactivity on child externalizing behaviors over time. The full two-level equation for the effects of center care is shown below:

Level 1

Externalizing behaviors = β0 + β1 (time) + β2 (parental overreactivity) + error

Level 2

β0, β1, β2 = γ0 + γ1 (center ECE) + γ2 (birth parent regulation) + γ3 (center ECE × birth parent regulation) + error

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations of observed variables in this study, including exposure to center-based ECE, components of the birth parent regulation composite and the adoptive parenting variables, and child externalizing behaviors. Zero-order correlations revealed nonsignificant associations among predictor variables. Child externalizing behaviors were related to more overreactive parenting (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Information

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Center-based ECE (by age 4.5 years) | 68% yes | |

| Birth Parent Regulation (z-score composite) | −.03 | .58 |

| Fear (birth mother, father) | 3.78, 2.96 | .97, 1.00 |

| Frustration (birth mother, father) | 3.96, 3.90 | 1.07, .99 |

| Sadness (birth mother, father) | 4.42, 3.67 | .91, .89 |

| Discomfort (birth mother, father) | 3.94, 3.40 | 1.17, 1.08 |

| Activation Control (birth mother, father) | 4.65, 4.83 | .98, .92 |

| Attentional Control (birth mother, father) | 4.26, 4.58 | 1.17, 1.13 |

| Inhibitory Control (birth mother, father) | 4.08, 4.33 | .85, .82 |

| Adoptive Parent Overreactivity | ||

| 9-month (adoptive mother, father) | 1.73, 1.83 | .56, .61 |

| 18-month (adoptive mother, father) | 1.88, 1.92 | .58, .59 |

| 27-month (adoptive mother, father) | 2.09, 2.08 | .60, .59 |

| 4.5-year (adoptive mother, father) | 2.38, 2.32 | .56, .64 |

| 6-year (adoptive mother, father) | 2.39, 2.34 | .69, .66 |

| Child Externalizing Behaviors | ||

| 18-month (mother-, father-report) | 47.93, 45.80 | 8.00, 8.40 |

| 27-month (mother-, father-report) | 48.49, 46.86 | 8.30, 8.60 |

| 4.5-year (mother-, father-report) | 50.05, 48.04 | 8.70, 8.90 |

| 6-year (mother-, father-report) | 46.04, 44.88 | 8.80, 9.00 |

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Center-based ECE | — | |||

| 2. Birth parent regulation | −.08 | — | ||

| 3. Adoptive parent overreactivity | .02 | −.02 | — | |

| 4. CBCL externalizing behaviors | −.03 | −.08 | .34** | — |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Correlations based on the mean of each variable across assessments. These associations were consistent across assessment times.

Covariates

Several variables that could influence child externalizing behaviors were tested as possible covariates in analyses. These included child age, child sex, adoptive family socioeconomic status, adoption openness, prenatal and obstetric risk (i.e., drug exposure, maternal health problems prior to and at the birth), birth mother IQ (WAIS Information scores), age of entry into group-based ECE, and the amount of time children spent in their current ECE arrangements. None of these variables was found to relate significantly to child externalizing behaviors, nor did their removal change any of the model effects. Thus, the more parsimonious models containing only hypothesized study predictors are reported.

HLM Model Tests: Baseline Model

Prior to adding explanatory predictors, a baseline unconditional model of child externalizing behaviors was fit to the data, to which subsequent models could be compared. A linear model of externalizing behaviors from age 18 months – 6 years was selected, centered at the final timepoint so that the intercept represented externalizing behaviors at age 6. This model improved in fit over an intercept-only model, χ2(3) = 28.90, p < .001, and a quadratic model failed to yield an improvement over the linear model. While the linear term was negative, but nonsignificant overall (β = −.15, p = .44), significant between-family variability (χ2[199] = 319.84, p < .001) suggested that children varied in their trajectories of externalizing behaviors; this variability could be explained by adding Level 2 predictors.

HLM Model Tests: Main Effects

As shown in Table 3, overreactive parenting predicted child externalizing behaviors within occasions, as a Level 1 time-varying covariate (β = .14, p < .001). This effect varied across children, χ2(198) = 284.27, p < .001, supporting the inclusion of predictors to explain the size of the association between overreactive parenting and child externalizing behaviors. In other words, children who had more overreactive parents exhibited more externalizing behavior, but the degree of association varied across families, suggesting that perhaps other factors (genetic background, center-based ECE) might play a role in determining how closely overreactive parenting and child externalizing behaviors were linked. Neither attendance in center-based ECE nor birth parent regulation at Level 2 predicted the intercept or slope of externalizing behaviors as main effects.

Table 3.

Effects of Center-Based ECE, Overreactivity, Birth Parent Regulation, and their Interactions on Child Externalizing Behaviors

| Predictors of Externalizing Behaviors | Standardized Coefficient |

p |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept (age 6 externalizing behaviors) | −.052 | .43 |

| Predictors of the intercept | ||

| Center-based ECE | −.009 | .92 |

| Birth parent regulation | −.083 | .20 |

| Center-based ECE × birth parent regulation | −.017 | .80 |

| Slope (18 months – 6 years) | −.022 | .32 |

| Predictors of the slope | ||

| Center-based ECE | .032 | .21 |

| Birth parent regulation | −.006 | .80 |

| Center-based ECE × birth parent regulation | −.042 | .03 |

| Adoptive Parent Overreactivity (time-varying) | .130 | < .001 |

| Predictors of the effect of adoptive parent overreactivity on externalizing |

||

| Center-based ECE (2-way interaction) | .085 | .07 |

| Birth parent regulation (2-way interaction) | .052 | .18 |

| Center-based ECE × birth parent regulation (3-way interaction) |

−.120 | .004 |

HLM Model Tests: Interaction Effects

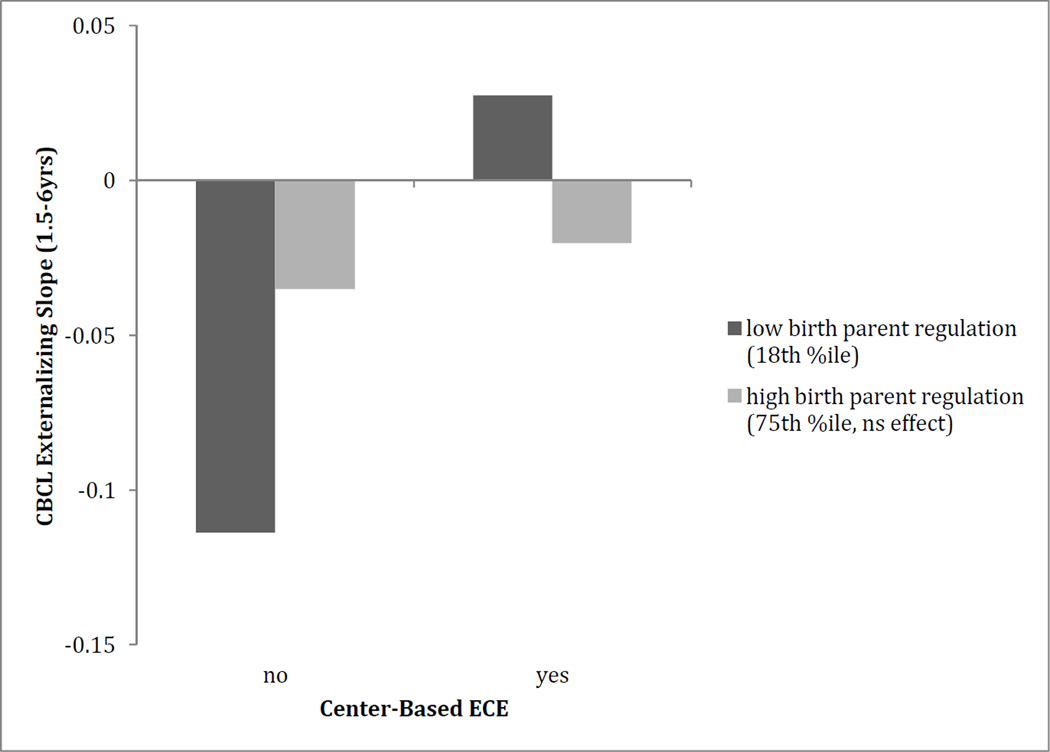

Models including interactions between center-based ECE and birth parent regulation were tested to address two research questions. The question of whether children with birth parents who had poor regulation would be more sensitive than other children to overreactive parenting was tested by way of a 2-way interaction between birth parent regulation and overreactive parenting predicting externalizing behavior intercepts and slopes. Table 3 shows that birth parent regulation moderated the impact of being in center–based ECE on trajectories of child externalizing behaviors (see Table 3). Probing the region of significance for this interaction revealed that attending center-based ECE predicted a more positive externalizing behavior slope (reflecting increased externalizing behaviors) only for children whose birth parents scored −.54 or lower on regulation (18th percentile; see Figure 1). Follow-up analysis revealed modest effect sizes; β = .09 in the middle of the region of significance (9th percentile) and β = .15 at the lowest value in the region of significance. At no value of birth parent regulation did being in ECE predict a more negative slope (reduction) in child externalizing behaviors.

Figure 1.

Center-based ECE interacts with birth parent regulation to predict trajectories of child externalizing behaviors (shown at lower bound of region of significance). Y axis represents the linear slope of child externalizing scores from 18 months to 6 years.

The second research question—whether the combination of having a birth parent with poor regulation and exposure to center-based ECE would amplify the magnitude of the association between overreactive parenting and externalizing behaviors—was tested by a three-way interaction. The interaction of birth parent regulation and exposure to center-based care was included as a predictor not only of children’s externalizing behavior intercepts and slopes, but also of the effect of overreactive parenting on child externalizing behaviors over time. Results pointed to a three-way interaction in which the combination of exposure to center-based ECE and birth parent regulation moderated the effect of overreactive parenting on externalizing behaviors (Table 3). Probing the region of significance for this three-way interaction revealed that children who attended center-based ECE were more sensitive to the effect of overreactive parenting when they also had genetic liability for dysregulation, indicated by birth parent regulation scores of −.08 or lower (48th percentile). Follow-up analysis revealed modest to moderate effect sizes; β = .16 in the middle of the region of significance (24th percentile) and β = .42 at the lowest value in the region of significance. For a small proportion of children whose birth parents scored .99 or higher on regulation (96th percentile; n = 10), being in center care actually predicted a weaker effect of overreactive parenting on externalizing behaviors. Follow-up analysis revealed modest effect sizes; β = −.21 in the middle of the region of significance (98th percentile) and β = −.28 at the highest value in the region of significance.

This final model provided a significant improvement in fit over the baseline model, χ2(13) = 89.98, p < .001. In sum, the two-way interaction revealed that attending center-based ECE was only associated with increasing externalizing behaviors for children with a genetic liability for dysregulation. The three-way interaction indicated that children who experienced both genetic risk and exposure to center-based ECE were more sensitive to overreactive parenting than other children. This final model explained 8% of the variance in child externalizing behavior slopes and 10% of the variance in the effect of overreactive parenting on child externalizing behaviors.

Discussion

The current study examined interactions among genetic influences (birth parent regulation) and children’s early environments on their development of externalizing behaviors during the formative early childhood years from age 1.5 to 6. Children exhibited variability in development of externalizing behaviors during this period, which was predicted by interactions among genetic influences and children’s family (overreactive parenting) and out-of-home (center-based ECE) environments. Findings were consistent with the Diathesis-Stress model, which posits that genetic influences can enhance children’s sensitivity to potential environmental stressors (e.g., Zuckerman, 1999). In this study, attending center-based ECE was only associated with increasing externalizing behaviors for children with a genetic liability for dysregulation. Additionally, children who experienced both genetic risk and exposure to center-based ECE were more sensitive to overreactive parenting than other children.

Interaction between Genetic Variability and Center-Based ECE

Based on the Diathesis-Stress model (Zuckerman, 1999), we hypothesized that children with a genetic liability for behavioral dysregulation, assessed through poor birth parent regulation, would exhibit enhanced sensitivity to potentially adverse experiences (overreactive parenting, and exposure to center-based ECE). Results supported the hypothesis for exposure to center-based ECE; only children who had birth parents with poor regulation (below the 18th percentile) exhibited differences in their trajectories of externalizing behaviors based on whether or not they attended center-based ECE. For this group of children, attending center-based ECE was associated with increases in externalizing behaviors (illustrated in Figure 1). Children whose birth parents were better regulated did not show any significant effect of being in center-based ECE on their externalizing behaviors. This statistical interaction between genetic liability and exposure to center-based ECE on child externalizing behavior trajectories held up while accounting for associations between parenting and externalizing behavior at each measurement occasion. This finding has important implications for our understanding of ECE as a developmental context. American society is increasingly turning to preschool as a means of preparing children for success in school. Indeed, evidence suggests that center-based ECE can help children to gain cognitive and pre-academic skills (Belsky et al. 2007; Magnuson & Waldfogel, 2005; NICHD ECCRN, 2005). Yet findings of increased behavioral problems for children attending center-based ECE (e.g., Haskins, 1985; NICHD ECCRN, 2002, 2004; Pluess & Belsky, 2009) make it more difficult to ascertain the overall value of center-based ECE for children’s development. Even small increases in behavioral problems may have societal importance, considering both the large percentages of young children attending center-based ECE, and potential spillover effects to these children’s peers once they reach elementary school (e.g., Dmitrieva et al., 2007).

Findings from the current study contribute to an emerging line of research (Belsky & Pluess, 2013; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2005; Pluess & Belsky, 2009) investigating whether increased externalizing behavior is a typical response to center-based ECE or whether only select subgroups of children respond in this way. Findings are consistent with the Diathesis-Stress model, suggesting that children with genetic liability for dysregulation are those most likely to respond to center-based ECE with increasing externalizing behavior. These children may face more biological challenges in regulating their behavior than other children when they are faced with large peer groups and heightened social interaction and competition that are typical of center-based ECE. These results also contribute to continued conceptualization of the Diathesis-Stress model. Most prior studies of this model during early childhood have focused measurement of environmental stress on the home, or parent-child, context. Findings from the current study indicate that similar Diathesis-Stress mechanisms may be at play when considering how children respond to out-of-home settings (exposure to center-based ECE) during early childhood.

This finding stands in contrast to recent results described by Belsky and Pluess (2013), in which specific genetic markers did not moderate the effect of center-based care on children’s externalizing behavior. Rather, center-based care had a main effect on children’s externalizing behavior. Several explanations for this inconsistency across the two studies are possible, including that all three key variables were measured differently across the two studies. Belsky and Pluess (2013) utilized a molecular genetic approach (rather than an adoption design), examined teacher reports (rather than parent reports) of children’s externalizing behaviors, and assessed the proportion of time periods throughout early childhood that children attended (rather than whether or not they ever attended) center-based care. Any or all of these design differences could account for the discrepancy in findings. It is especially worth noting that the parent-offspring approach used here allows us to consider the moderating effects of the whole genome rather than of a specific gene. Therefore, it is not surprising that there may be differences in these moderating effects given the differences in the genetic variability under consideration. Further research in this area is needed.

It will be important for future investigations to examine potential underlying mechanisms linking center-based ECE to externalizing behaviors, such as stress-response biology and self-regulatory behaviors, in conjunction with both children’s genetic backgrounds and their temperaments. This type of additional research should, in turn, help to inform strategies that could be developed to meet the needs of children with biological risks for behavioral problems within the early learning settings that help to prepare them academically for school.

Future research should investigate whether children’s genetic backgrounds also increase their susceptibility to the positive environmental influences, in addition to the negative ones, of their ECE experiences, which would be consistent with Differential Susceptibility theory (e.g., Belsky & Pluess, 2009) or Biological Sensitivity to Context (e.g., Boyce & Ellis, 2005). The current study could not adequately address these theories because only negative environmental factors (i.e., overreactive parenting) and outcomes (i.e., externalizing behaviors) were examined, and the absence of a negative does not necessarily imply a positive. As discussed earlier, center-based ECE appears to benefit children’s early academic skills and quality ECE has been linked with better outcomes across a range of domains (e.g., NICHD ECCRN, 2002, 2004). Utilizing a molecular genetics approach, one recent study detected support for differential susceptibility with respect to some but not all interactions between genetics and ECE in predicting children’s development (Belsky & Pluess, 2013). More research in this area, utilizing both adoption and molecular genetic designs, is warranted.

Future work should also examine interactions between genetics and ECE on children’s development outside of the United States. Recent evidence suggests that ECE may not be linked with externalizing behavior in countries with very different sociopolitical context for ECE (e.g.., in Norway, which offers high quality center-based ECE to all families; Zachrisson, Dearing, Lekhal, & Toppelberg, 2013). Further research conducted in countries with varying sociopolitical contexts is needed for a broader understanding of which associations between ECE and children’s development are typical human responses and which vary by individual differences (e.g. genetics), sociopolitical context, or both.

Overreactive Parenting

Overreactive parenting was the only predictor in the present study that had a direct effect on externalizing behaviors. Findings were consistent with prior research (e.g., Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Shaw et al., 2003; Tremblay et al., 2004), documenting associations between overreactive or hostile/rejecting parenting and externalizing behaviors over time. Neither genetic variability nor exposure to center-based ECE had an independent effect on the magnitude of the association between overreactive parenting and children’s externalizing. However, when these two vulnerability factors were combined they magnified the effect of overreactive parenting on children’s externalizing behavior. This suggests that not only may genetic liability make it more difficult for children to cope with potential stresses of center-based ECE, but also that it can augment the effect of exposure to center-based ECE on children’s sensitivity to their parents. That is, children with multiple vulnerabilities (e.g., in both their genetic backgrounds and also in their exposure to center-based ECE) appear to have a heightened sensitivity to overreactive parenting on their development of externalizing behaviors.

These findings establish a foundation for future research on GxExE. In light of a growing body of evidence that children’s genetic background and/or temperament interact with both their ECE experiences (e.g., Belsky & Pluess, 2013; Phillips et al., 2011) and their home environments (e.g., Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Leve et al., 2009) in predicting developmental outcomes, more research on GxExE is needed. This work should examine a variety of outcome areas in addition to externalizing behavior, and should aim to clarify the circumstances in which GxExE is consistent with a Diathesis-Stress versus Biological Sensitivity to Context or Differential Susceptibility model (see Belsky & Pluess, 2013; Kochanska, Kim, Barry, & Philibert, 2011; Roisman, Newman, Fraley, Haltigan, Groh, & Haydon, 2012).

Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusions

The present study offers a new lens to the study of GxE in understanding children’s development of externalizing behaviors by examining out-of-home ECE as part of children’s environment. This approach is not only important in advancing the study of GxE, but it also contributes to the literature on ECE. An important line of work examines how characteristics of children and families moderate the effects of ECE on development (e.g., Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001; Pluess & Belsky, 2009). Findings from the current study contribute by documenting interactions between children’s genetics and their ECE experiences that impact development.

Several methodological strengths were incorporated into the present study. Most importantly, the prospective adoption design, where infants are adopted at birth and placed with non-relative adoptive parents, permitted the simultaneous examination of both environments (parenting, ECE), and genetic influences, as well as GxE without contamination by passive genotype × environment correlation (Rutter et al., 2001). We confirmed that G (birth parent regulation) was not significantly correlated with E (adoptive parent overreactivity) in this study. Additionally, extensive prior analyses with the current sample have shown no associations between birth parent self-regulation and adoptive parent characteristics (Leve et al., 2013).

The testing of adoption openness and prenatal and obstetric risk as covariates in the analyses, neither of which had a significant effect on externalizing behaviors, reduced the likelihood that the findings were influenced by prenatal factors or from sharing of information between birth parents and adoptive parents. Moreover, the longitudinal design and statistical modeling allowed for examination of within-time associations between overreactive parenting and externalizing behaviors, which is consistent with tenets of the coercive cycle model (e.g., Larsson et al., 2008; Patterson & Fisher, 2002; Scaramella et al., 2008; Shaw & Bell, 1993), established patterns of trajectories of externalizing problems (Shaw et al., 2003), and transactional processes between parenting and child behavior (Bell, 1968; Sameroff & Chandler, 1975).

Some limitations of the study should also be noted. First, the sample of adoptive families had limited ethnic and sociodemographic diversity, which affects the generalizability of findings. In addition, families that were not included in the present analyses due to missing data on predictor variables were somewhat less likely to have children attending center-based ECE and to have birth parents with poor regulation. Given these sample limitations, it is not possible to generalize the specific regions of significance (or the proportion of children falling within those regions) beyond this sample. That is, although findings provide evidence that children with genetic risk for dysregulation are more likely to respond to center-based ECE with increasing behavior problems, the actual percentage of children represented within the region of significance for this interaction in the current study (18%) may be different than the percentage of children that would be affected in the general population.

Another limitation was the use of parent-report data for all study measures; self-reports of overreactive parenting would have ideally been corroborated by direct observations of parent-child interactions that were coded for overreactive parenting. Unfortunately, such data were not available. Additionally, measures of the quality of children’s ECE experiences were not obtained. Yet one of the strengths of the present study was the inclusion of additional ECE variables (children’s age of entry into group-based care and the number of hours per week they attended center-based ECE) as covariates in the analysis. Although including a measure of ECE quality would have been optimal, it would not likely have altered the effect of center-based ECE on externalizing; prior research suggests that type and quality of care operate independently (e.g. NICHD ECCRN, 2002, 2004; Pluess & Belsky, 2009).

In conclusion, the current investigation indicates that genetic influences help to explain differences in the ways that children respond to the environments that they encounter both in-home and out-of-home. Attending center-based ECE may only be associated with increasing behavior problems for subgroups of children, such as those whose genetic backgrounds make it more challenging for them to regulate their behavior. Further research is necessary to better understand which children are most sensitive to the positive (e.g., gains in early academic skills) and negative (e.g., increases in behavior problems) effects of experiences in ECE. This work will have important implications for programs and policies seeking to enhance children’s readiness to succeed in school. Findings also highlight the importance of considering children’s development within multiple environmental contexts, in conjunction with their genetic backgrounds. Results provide initial evidence that efforts to minimize harsh or overreactive parenting may have the most potential to impact externalizing outcomes for children who have both genetic liability for dysregulation and attend center-based ECE.

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by R01 HD042608; NICHD, NIDA, and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI Years 1–5: David Reiss; PI Years 6–10: Leslie D. Leve), R01 DA020585 from NIDA, NIMH and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Jenae Neiderhiser), and R01 MH092118 (Multiple PIs: Jenae Neiderhiser and Leslie Leve) The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or NIH.

Contributor Information

Shannon T. Lipscomb, Oregon State University-Cascades

Heidemarie Laurent, University of Oregon.

Jenae M. Neiderhiser, The Pennsylvania State University

Daniel S. Shaw, University of Pittsburgh

Misaki N. Natsuaki, University of California, Riverside

David Reiss, Yale Child Study Center.

Leslie D. Leve, Oregon Social Learning Center

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. Available from http://www.aseba.org. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O’Leary SG, Wolf LS, Acker MM. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;9:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH. Gene-environment interaction of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) and observed maternal insensitivity predicting externalizing behavior in preschoolers. Developmental Psychobiology. 2006;48:406–409. doi: 10.1002/dev.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:982–995. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Burchinal M, McCartney K, Vandell DL, Clarke-Steward KA, Owen M NICHD ECCRN. Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child Development. 2007;78:681–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis-stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Genetic moderation of early child-care effects on social functioning across childhood: a developmental analysis. Child Development. 2013 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Domínguez X, Bell ER, Rouse HL, Fantuzzo JW. Relations between behavior problems in classroom social and learning situations and peer social competence in Head Start and kindergarten. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2010;18:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Fantuzzo JW. Preschool behavior problems in classroom learning situations and literacy outcomes in kindergarten and first grade. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2011;26:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: A meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:609–637. doi: 10.1037/a0015702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button TMM, Scourfield J, Martin N, Purcell S, McGuffin P. Family dysfunction interacts with genes in the causation of antisocial symptoms. Behavior Genetics. 2005;35:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s10519-004-0826-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadoret RJ, Winokur G, Langbehn D, Troughton E, Yates W, Stewart M. Depression spectrum disease: The role of gene-environment interaction. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:892–899. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.892. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/data/Journals/AJP/3665/892.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotional regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;59:250–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM. Infant temperament moderates associations between childcare type and quantity and externalizing and internalizing behaviors at 2½ years. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Arousal, affect, and attention as components of temperament. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:958–966. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettling AC, Gunnar MR, Donzella B. Cortisol levels of young children in full-day child care centers: Relations with age and temperament. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:519–536. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLalla FL, Elam KK. Genetic and gene-environment interaction effects on preschoolers' social behaviors. Developmental Psychobiology. 2009;51:451–464. doi: 10.1002/dev.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva J, Steinberg L, Belsky J. Child-care history, classroom composition, and children's functioning in kindergarten. Psychological Science. 2007;18:1032–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzella B, Gunnar M, Krueger W, Alwin J. Cortisol and vagal tone responses to competitive challenges in preschoolers: Associations with temperament. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;37:209–220. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(2000)37:4<209::aid-dev1>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes R, Hanish L, Martin CL. Children at play: The role of peers in understanding the effects of child care. Child Development. 2003;74:1039–1043. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, McWayne C. The relationship between peer-play interactions in the family context and dimensions of school readiness for low-income preschool children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Button TMM, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Hetherington M. Parenting and adolescent antisocial behavior and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:457–465. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JR, Saudino KJ, Asherson P. The genetic etiology of inhibitory control and behavior problems at 24 months of age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:1155–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie CF, Phifer J, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. Risk and resilience: Genetic and environmental influences on development of the stress response. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:984–992. doi: 10.1002/da.20605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Lemery KS, Buss KA, Campos JJ. Genetic analysis of focal aspects of infant temperament. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:972–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins R. Public school aggression among children with varying day-care experience. Child Development. 1985;56:689–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, South SC, Dirago AC, Iacono WG, McGue M. Environmental adversity and increasing genetic risk for externalizing disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:640–648. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice LM, Cottone EA, Mashburn A, Rimm-Kaufman SE. Relationships between teachers and preschoolers who are at risk: contribution of children’s language skills, temperamentally based attributes, and gender. Early Education & Development. 2008;19:600–621. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, Barry RA, Philibert RA. Children’s genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children’s competence: diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:605–616. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Viding E, Rijsdijk FV, Plomin R. Relationships between parental negatively and childhood antisocial behavior over time: A bidirectional effects model in a longitudinal genetically informed design. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:633–645. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw D, Scaramella LV, Reiss D. Structured parenting of toddlers at high versus low genetic risk: Two pathways to child problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:1102–1109. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b8bfc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D. The Early Growth and Development Study: A prospective adoption study of child behavior from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;16:412–423. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.126. PMC: 3572752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Shaw D, Neiderhiser JM, Scaramella LV, Ge X, Reiss D. Negative emotionality and externalizing behaviors in toddlerhood: overreactive parenting as a moderator of genetic influences. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:167–179. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb S, Bridges M, Bassok D, Fuller B, Rumberger RW. How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Economics of Education Review. 2007;26:52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Parenting and its effects on children: On reading and misreading behavior genetics. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson K, Waldfogel J. Early childhood care and education: Effects on ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. Future of Children. 2005;15:169–196. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWayne CM, Cheung C. A picture of strength: Preschool competencies mediate the effects of early behavior problems on later academic and social adjustment for Head Start children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Early child care and children’s development prior to school entry: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. American Educational Research Journal. 2002;39:133–164. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Type of child care and children’s development at 54 months. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2004;19:203–230. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. American Educational Research Journal. 2005;42:537–570. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Caspi A, DeFries JC, Plomin R. Genotype-environment interaction in children's adjustment to parental separation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:849–856. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Deater-Deckard K, Fulker D, Rutter M, Plomin R. Genotype environment correlations in late childhood and early adolescence: Antisocial behavioral problems and coercive parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:970–981. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Fisher PA. Recent developments in our understanding of parenting: Bidirectional effects, causal models, and the search for parsimony. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Practical and Applied Parenting. 2nd ed. Vol. 5. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Peisner-Feinberg E, Burchinal M, Clifford R, Culkin M, Howes C, Kagan S, Yazejian N. The relation of preschool child-care quality to children’s cognitive and social developmental trajectories through second grade. Child Development. 2001;72:1534–1553. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DA, Fox NA, Gunnar MR. Same place, different experiences: bringing individual differences to research in child care. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Coon H, Carey G, DeFries JC, Fulker DW. Parent-offspring and sibling adoption analyses of parental ratings of temperament in infancy and childhood. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:705–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC. Origins of individual differences in infancy: The Colorado adoption project. Orlando: Academic; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, Knopik VS, Neiderhiser JM. Behavioral genetics. 6th Ed. New York: Worth Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pluess Belsky. Differential susceptibility to rearing experience: the case of childcare. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:396–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd Ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reef J, Diamantopoulou S, van Meurs I, Verhulst FC, van der Ende J. Developmental trajectories of child to adolescent externalizing behavior and adult DSM-IV disorder: Results of a 24-year longitudinal study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46:1233–1241. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM. How Genes and the Social Environment Moderate Each Other: Four Mechanisms. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301408. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:490–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Newman DA, Fraley RC, Haltigan JD, Groh AM, Haydon KC. Distinguishing differential susceptibility from diathesis–stress: Recommendations for evaluating interaction effects. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:389–409. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. Vol. 3. New York: John Wiley; 1998. pp. 106–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE. Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:122–135. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:55–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: Multiple varieties but real effects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:226–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Pickles A, Murray R, Eaves LJ. Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causal effects on behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:291–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Silberg J. Gene-environment interplay in relation to emotional and behavioral disturbance. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:463–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Chandler MJ. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaker casualty. In: Horowitz FD, editor. Review of child development research. Vol. 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hempill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13:142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Saudino KJ. Special Article: Behavioral genetics and child temperament. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005;26:214–223. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200506000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella L, Neppl T, Ontai L, Conger R. Consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage across three generations: Parenting behavior and child externalizing behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:725–733. doi: 10.1037/a0013190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Winslow EB, Owens EB, Vondra JI, Cohn JF, Bell RQ. The development of early externalizing behaviors among children from low-income families: A transformational perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:95–107. doi: 10.1023/a:1022665704584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin D. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stams GJ, Juffer F, van Ijzendoorn MH. Maternal sensitivity, infant attachment, and temperament in early childhood predict adjustment in middle childhood: The case of adopted children and their biologically unrelated parents. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:806–821. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tout K, de Haan M, Kipp-Campbell E, Gunnar MR. Social behavior correlates of cortisol activity in daycare: Gender differences and time-of-day effects. Child Development. 1998;69:1247–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, S´eguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo PD, Boivin M, Japel C. Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e43–e50. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics, 2010 (NCES 2011-015) 2011a Chapter 2. Retrieved from: http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76.

- U.S. Department of Education. Race to the Top – Early Learning Challenge. 2011b Retrieved from: http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop-earlylearningchallenge/index.html.

- Vitaro F, Barker ED, Boivin M, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE. Do early difficult temperament and harsh parenting differentially predict reactive and proactive aggression? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:685–695. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watamura SE, Donzella B, Alwin J, Gunnar MR. Morning to afternoon increases in cortisol concentrations for infants and toddlers at child care: Age differences and behavioral correlates. Child Development. 2003;74:1006–1020. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JE, Harden BJ. Teacher-child relationships and children’s externalizing behaviors in Head Start. NHSA Dialog. 2010;13:141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zachrisson HD, Dearing E, Lekhal R, Toppelberg CO. Little evidence that time in child care causes externalizing problems during early childhood in Norway. Child Development. 2013 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Vulnerability to psychopathology: A biosocial model. Washington: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]