Abstract

Background

Recent studies emphasize the role of BRAF as a genetic marker for prediction, prognosis and risk stratification in colorectal cancer. Earlier studies have reported the incidence of BRAF mutations in the range of 5-20% in colorectal carcinomas (CRC) and are predominantly seen in the serrated adenoma-carcinoma pathway characterized by microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and hypermethylation of the MLH1 gene in the setting of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). Due to the lack of data on the true incidence of BRAF mutations in Saudi Arabia, we sought to analyze the incidence of BRAF mutations in this ethnic group.

Methods

770 CRC cases were analyzed for BRAF and KRAS mutations by direct DNA sequencing.

Results

BRAF gene mutations were seen in 2.5% (19/757) CRC analyzed and BRAF V600E somatic mutation constituted 90% (17/19) of all BRAF mutations. BRAF mutations were significantly associated with right sided tumors (p = 0.0019), MSI-H status (p = 0.0144), CIMP (p = 0.0017) and a high proliferative index of Ki67 expression (p = 0.0162). Incidence of KRAS mutations was 28.6% (216/755) and a mutual exclusivity was noted with BRAF mutations (p = 0.0518; a trend was seen).

Conclusion

Our results highlight the low incidence of BRAF mutations and CIMP in CRC from Saudi Arabia. This could be attributed to ethnic differences and warrant further investigation to elucidate the effect of other environmental and genetic factors. These findings indirectly suggest the possibility of a higher incidence of familial hereditary colorectal cancers especially Hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome /Lynch Syndrome (LS) in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, BRAF mutation, KRAS mutation, Microsatellite instability (MSI), Lynch Syndrome (LS), Hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome

Introduction

A complex network of genes are required for maintaining the cellular homeostasis in colorectal tissue. In the original multistep progression model of colorectal cancer (CRC) first proposed by Vogelstein et al, normal colonic epithelium gets transformed into benign (adenoma) neoplastic epithelium followed by full blown invasive cancer and eventually metastasis [1]. Over the years, significant advances in molecular genetics and caner biology have led to the understanding that there exist 3 distinct molecular phenotypes of CRC: (1) chromosomal instability(CIN) [2]; (2) microsatellite instability(MSI) [3]; and (3) the recently discovered sessile and traditional serrated adenomas, a subset of hyperplasic polyps that progress to serrated carcinomas [4].

Some of the key signaling pathways implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis are Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling (EGFR) pathway, WNT signaling [1] and transforming growth factor-β (TGF β) signaling [5]. Translational research has resulted in the bench-to-bedside application of biomarkers like KRAS, BRAF and PI3K for personalized medicine [6]. One of the key determinants of response to panitumumab and cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer is the presence of mutations in the KRAS gene [7,8]. Testing for certain “activating” mutations in the KRAS gene is currently one of the most widely employed methods to predict responsiveness to EGFR inhibitors. Patients with presence of KRAS mutations in their tumors do not respond to EGFR inhibitors. On the other hand, a significant proportion of CRC patients with the wild-type (normal) KRAS gene fail to respond to EGFR inhibitors and mutations in other genes such as PIK3CA/BRAF/NRAS/PTEN/TP53 have been implicated for resistance in this subgroup of patients [7-9]. BRAF mutations are known to be mutually exclusive with KRAS mutations and Vaughn et al have reported that almost 8% of the CRC subgroup with wild type KRAS gene had BRAF mutations; these patients would receive EGFR inhibitors but would be unresponsive to therapy [8].

Constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway regulates cellular proliferation, differentiation, and death. Oncogenic mutations in the v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) in CRC were first described by Davies et. al and the commonest mutation was a single phosphomimetic substitution in the kinase activation domain (V600E) that led to activation of the MAPK pathway [10] Although BRAF mutations have been identified in a variety of cancers, their highest incidence to the tune of almost 60% is seen in melanomas [10]. The CRC subset that originates from advanced serrated polyps have a distinct molecular phenotype characterized by widespread hypermethylation of CpG islands in the promoter regions of genes, referred to as the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) [11], microsatellite instability (MSI) and oncogenic mutations in BRAF gene [4,12,13]. Testing for BRAF mutation is beneficial in judicious selection of patients for targeted therapy [8,9] and also a cost effective approach in the HNPCC (Hereditary Non-polyposis Colorectal Cancer) workup; presence of BRAF mutation with absence of MLH1 protein is indicative of sporadic CRC [14,15].

In this study we comprehensively investigated the incidence of BRAF mutations in Saudi CRC and its clinico-pathological correlation, its association with molecular markers and overall survival.

Materials and methods

Patients’ selection and TMA construction

A total of 770 patients with CRC diagnosed between 1990 and 2011 were randomly selected from King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSHRC), and Security Forces Hospital (SFH), Riyadh. A colorectal tissue microarray was constructed comprising of 770 CRC samples as described previously [16]. Clinical and histopathological data were available for all these patients. Patients with colon cancer underwent surgical colonic resection and those with rectal cancer underwent anterior resection or abdominoperineal resection. All node-positive colon cancers received 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy. A vast majority of the rectal cancers received radiotherapy alone or chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. Colorectal Unit, Department of Surgery (KFSHRC and SFH), provided long-term follow-up data about the date and cause of death for this cohort of patients. Follow-up was calculated from the date of resection of the primary tumor, and all surviving cases were censored for survival analysis on 31st December 2011. Two pathologists (P.B., S.P.) reviewed all tumors for grade and histological subtype. The institutional review board of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre approved the study.

DNA isolation

DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded CRC tissues using Gentra DNA isolation kit (Gentra, Minneapolis, MN, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations as described previously [17].

PCR and DNA sequencing for KRAS and BRAF gene

KRAS and BRAF mutation analysis was performed on 755 and 757 CRC samples respectively. Primer 3 software was used to design the primers for Exon 15 of BRAF; Exon 1, 2 of KRAS (Table 1). The PCR sequencing protocol was same as described earlier [17]. The samples were finally analyzed on an ABI PRISM 3100xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Table 1.

Primer sequence of BRAF and KRAS gene

| Exon | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

|

BRAF

|

|

|

| Exon 15 |

TGCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAATG |

AGCATCTCAGGGCCAAAAAT |

|

KRAS

|

|

|

| Exon 1 |

TTAACCTTATGTGTGACATGTTCTAA |

AGAATGGTCCTGCACCAGTAA |

| Exon 2 | CCAGACTGTGTTTCTCCCTTC | TTTAAACCCACCTATAATGGTGAA |

Microsatellite markers and analyses

Allelic imbalances were measured by performing microsatellite analysis on all matched normal and tumor tissue by PCR amplification. A reference panel of five pairs of microsatellite primers, comprising two mononucleotide microsatellites (BAT25, BAT26) and three dinucleotide microsatellites (DS123, D5S346 and D17S250) were used to determine tumor MSI status [3]. Multiplex PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl using 50 ng of genomic DNA, 2.5 μl 10 × Taq buffer, 1.5 μl MgCl2 (25 mM), 10 pmol of fluorescent-labeled primers, 0.05 μl dNTP (10 mM) and 0.2 μl Taq polymerase (1 Uμl − 1; all reagents were from Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). PCR was performed using an MJ Research PTC-200 thermocycler. The samples in which the novel alleles were found at one, and two or more of those five loci were assigned MSI-L and MSI-H respectively, and whereas samples without novel alleles at any one of those loci were assigned MSS.

Statistical analysis

The JMP 10.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) software package was used for data analyses. Survival curves were generated using Kaplan-Meier method, with significance evaluated using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Risk ratio was calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinico-pathologic data

The characteristics of the 770 CRC patients are described earlier [18]. The median age at the time of surgery was 57 years (inter quartile range [IQR], 47.7 -68.0 years). The 5 year overall survival of our study population was 70.6%.

BRAF mutation and their clinico-pathological correlation

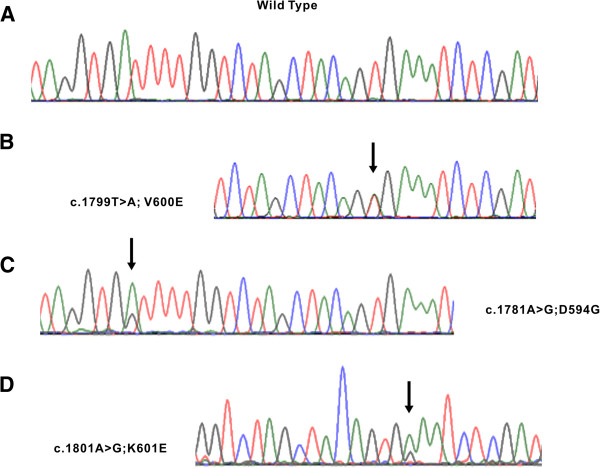

Seven hundred fifty seven colorectal cancer cases were analyzed for BRAF mutations and the remaining 13 cases were not interpretable due to insufficient amount of DNA and other technical reasons. Of the 757 cases analyzed for BRAF status, BRAF mutations were observed in nineteen cases and the incidence of BRAF in Saudi colorectal cancer was 2.5%( 19/757) (Table 2). Surprisingly this is among the lowest incidence of BRAF mutations reported in literature (Tables 3 and 4). Of these 19 CRC with BRAF mutations, 17 were seen in the V600E type and the other 2 were seen in V594G and V601E (Table 3 and Figure 1). To reconfirm these results and rule out the fact that we were missing any BRAF mutations due to tumor heterogeneity issues, cancer tissue was re-punched from 2-3 different tumor areas and BRAF analysis was repeated on 400 of these 757 samples. Repeat Sanger sequencing did not show any discordance with earlier results and failed to reveal any new cases with BRAF mutation. As shown in Table 2, CRC with BRAF mutations were significantly associated with right sided tumors (p = 0.0019), microsatellite instable MSI-H status (p = 0.0144) and CIMP high phenotype (p = 00017). Of the 19 cases with BRAF mutation, MSI-H, MSI-L and MSS were 6 cases (31.6%), 5 cases (26.3%) and 8(42.1%) cases respectively. The degree of Ki-67 staining as a measure of proliferative index was significantly higher in the BRAF mutation positive CRC group (88.89 ± 12.78) as compared to the BRAF mutation negative group (80.60 ± 25.30, p = 0.0162; Students T test; Additional file 1: Figure S1). A statistical trend was noted with presence of BRAF mutation and older age (age > 50; p = 0.0938) and a mutual exclusivity was observed with KRAS mutations (p = 0.0518; a statistical trend was noted). BRAF mutations were not associated with gender, histology subtype, tumor differentiation and Stage.

Table 2.

Correlation of BRAF Mutation with clinico-pathological parameters in colorectal carcinoma

| |

Total |

Positive |

Negative |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

|

Total number of cases |

757 |

|

19 |

2.5 |

738 |

97.5 |

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| < 50 years |

246 |

32.5 |

3 |

1.2 |

243 |

98.8 |

0.0938 |

| > 50 years |

511 |

67.5 |

16 |

3.1 |

495 |

97.9 |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

394 |

52.0 |

11 |

2.8 |

383 |

97.2 |

0.6044 |

| Female |

363 |

48.0 |

8 |

2.2 |

355 |

97.8 |

|

|

Tumour site* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Left colon |

600 |

83.0 |

10 |

1.7 |

590 |

98.3 |

0.0019 |

| Right colon |

123 |

17.0 |

9 |

7.3 |

114 |

92.7 |

|

|

Histological type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Adenocarcinoma |

673 |

88.9 |

18 |

2.7 |

655 |

97.3 |

0.3673 |

| Mucinous Carcinoma |

84 |

11.1 |

1 |

1.2 |

83 |

98.8 |

|

|

Tumour stage* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

88 |

12.2 |

4 |

4.6 |

84 |

95.4 |

0.6853 |

| II |

255 |

35.3 |

7 |

2.7 |

248 |

97.3 |

|

| III |

289 |

40.0 |

6 |

2.1 |

283 |

97.9 |

|

| IV |

90 |

12.5 |

2 |

2.2 |

88 |

97.8 |

|

|

Differentiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well |

74 |

9.8 |

2 |

2.7 |

72 |

97.3 |

0.8887 |

| Moderate |

590 |

77.9 |

14 |

2.4 |

576 |

97.6 |

|

| Poor |

93 |

12.3 |

3 |

3.2 |

90 |

96.8 |

|

|

MSI-Molecular* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSI-H |

81 |

11.1 |

6 |

7.4 |

75 |

92.6 |

0.0144 |

| MSI-S/L |

651 |

88.9 |

13 |

2.0 |

638 |

98.0 |

|

|

KRAS

Mutation* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Positive |

216 |

28.7 |

2 |

0.9 |

214 |

99.1 |

0.0518 |

| Negative |

537 |

71.3 |

17 |

3.2 |

520 |

96.8 |

|

|

CIMP* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| High |

24 |

5.1 |

4 |

16.7 |

20 |

83.3 |

0.0017 |

| Low & middle | 444 | 94.9 | 8 | 1.8 | 436 | 98.2 | |

*Data were not available (NA) for some cases for tumor site (NA = 34), Stage (NA = 35), MSI-Molecular (NA = 25), KRAS Mutation (NA = 4), and CIMP (NA = 289).

Table 3.

Clinical information, pathologic diagnosis, BRAF and KRAS testing results

| Case # | AGE | Gender | Histology Type | Site | Grade | Stage | BRAF | KRAS | CIMP | MSI-PCR |

Pre-existing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoma | |||||||||||

|

BRAF-1 |

60 |

Male |

AC |

Caecum |

2 |

I |

V601E |

Codon 13 |

Low CIMP |

MSI-L |

Tubular adenoma |

|

BRAF-2 |

47 |

Male |

AC |

Ascending colon |

2 |

I |

V600E |

Codon 13 |

NA |

MSI-S |

Hyperplastic polyp |

| SERRATED ADENOMA | |||||||||||

|

BRAF-3 |

71 |

Female |

AC |

Rt colon |

1 |

III |

V600E |

WT |

NA |

MSI-H |

Unremarkablemucosa |

|

BRAF-4 |

57 |

Female |

AC |

Rt colon |

3 |

IV |

V600E |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-S |

Unremarkablemucosa |

|

BRAF-5 |

67 |

Male |

AC |

Recto sigmoid |

2 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-S |

Unremarkablemucosa |

|

BRAF-6 |

74 |

Female |

AC |

Rt colon |

3 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-H |

Unremarkablemucosa |

|

BRAF-7 |

66 |

Male |

AC |

Ascending colon |

2 |

III |

V594G |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-L |

Adenoma |

|

BRAF-8 |

68 |

Male |

AC |

Rt colon |

2 |

IV |

V600E |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-S |

Unremarkablemucosa. |

|

BRAF-9 |

61 |

Female |

AC |

Rt colon |

1 |

I |

V600E |

WT |

High CIMP |

MSI-H |

Small hyperplasticpolyps |

|

BRAF-10 |

46 |

Male |

AC |

Sigmoid |

2 |

I |

V600E |

WT |

NA |

MSI-L |

Hyperplastic polyp |

|

BRAF-11 |

34 |

Male |

AC |

Recto sigmoid |

2 |

III |

V600E |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-S |

Unremarkablemucosa |

|

BRAF-12 |

71 |

Male |

AC |

Sigmoid |

2 |

III |

V600E |

WT |

NA |

MSI-S |

Hyperplastic polyp |

|

BRAF-13 |

59 |

Male |

AC |

Rectal |

2 |

III |

V600E |

WT |

High CIMP |

MSI-S |

Tubular adenoma |

|

BRAF-14 |

66 |

Female |

AC |

Rt colon |

2 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

NA |

MSI-H |

Unremarkable mucosa |

|

BRAF-15 |

66 |

Male |

AC |

Sigmoid colon |

2 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

Low CIMP |

MSI-S |

No colonic mucosa seen |

|

BRAF-16 |

73 |

Female |

AC |

Rt colon |

3 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

High CIMP |

MSI-H |

Unremarkable mucosa |

|

BRAF-17 |

72 |

Male |

AC |

Rt colon |

2 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

High CIMP |

MSI-H |

Unremarkable mucosa |

|

BRAF-18 |

74 |

Female |

AC |

Sigmoid colon |

2 |

II |

V600E |

WT |

NA |

MSI-L |

Unremarkable mucosa |

| BRAF-19 | 55 | Female | MC | Recto sigmoid | 2 | III | V600E | WT | NA | MSI-L | Unremarkable mucosa |

Table 4.

Summary of previous studies on BRAF mutation in colorectal carcinoma

| Study | Country | % with BRAF | BRAF mutation detected | Methods of mutation detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Li-Ling H, 2012 |

Taiwan |

1.1 |

2/182 |

High-resolution melting point (HRM) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for BRAF V600E mutations |

|

Li H , 2011 |

China |

7 |

14/200 |

Sequenced by Pyrosequencer PyroMark ID system-Exon 15, V600E |

|

Liou J, 2011 |

China |

3.8 |

12/314 |

Sequencing of exons 11 and 15 |

|

Yokota T, 2011 |

Japan |

4.7 |

15/319 |

Cycleave PCR technique for V600E mutation |

|

Nakanishi R, 2012 |

Japan |

6.7 |

17/254 |

BRAF pyrokit pyrosequencing |

|

Ajay Goel, 2009 |

Israel |

18.7 |

24/128 |

Direct sequencing using the BigDye version 1.1 cycle-sequencing kit |

|

Rozek L, 2010 |

Israel |

5 |

65/1300 |

Direct sequencing of exon 15 of BRAF |

|

Price T, 2011 |

Australia |

10.6 |

33/315 |

High-resolution melting point (HRM) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for BRAF V600E mutations |

|

Tran B, 2011 |

Australia |

11 |

57/524 |

Mutation-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction assay. |

|

Di Nicolantonio, 2008 |

Italy |

10 |

11/113 |

Automated sequencing by ABI PRISM 3730 exon15 |

|

Richman S, 2009 |

UK |

7.9 |

422/711 |

Pyrosequenced on a PyroMark ID system (Biotage AB) Codon 600 |

|

Roth A, 2009 |

Switzerland |

7.9 |

103/1307 |

Allelic discrimination assay on a 7500 real-time polymerase chain reaction for V600E |

|

Zlobec I, 2010 |

Switzerland |

12 |

45/374 |

BRAF (exon 15 codon 600) direct sequencing of single-stranded PCR products using the BigDyeVR Terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing kit |

|

Farina-Sarasqueta A, 2010 |

Netherlands |

19.8 |

59/297 |

V600E mutation on the BRAF gene by real-time PCRLight Cycler v2.0 (Roche) |

|

Saridaki Z, 2010 |

Greece |

8.3 |

12/144 |

Real-time PCR using the allelic discrimination method with ABI PRISM 7900 T Sequence Detection System |

|

Modest D, 2012 |

Germany |

11.6 |

17/146 |

Exons 11 and 15 of the BRAFpyro-sequencing |

|

Samowitz W, 2005 |

USA |

9.5 |

87/911 |

Sequencing in both directions |

|

Shaukat A,2010 |

USA |

21.8 |

36/165 |

BRAF V600E mutation -Mutector II BRAF/Ras mutation detection panel assay kit |

|

Kalady M,2012 |

USA |

12 |

56/475 |

Direct sequencing |

| Ogino S,2012 | USA | 15 | 11/75 | c.1799 T > A (p.V600E) mutation |

Figure 1.

Example of BRAF gene mutations in CRC. Sequencing traces of cases harboring wild type (A), and V600E (B), D594G (C) and K601E (D) mutations, respectively.

All the pathology reports of colonic biopsies and resection specimens and slides were reviewed to ascertain the presence of serrated adenomas in the 19 cases with BRAF mutations. We confirmed the presence of a serrated adenoma in only 1 case; hyperplastic polyps in 3 cases; tubular adenomas in 2 and the remaining 13 cases showed unremarkable colorectal mucosa.

KRAS mutation and their clinico-pathological correlation

In our series of 770 CRC samples 755 were analyzable for KRAS mutations and the incidence of KRAS mutations was 28.6% (216/755; Additional file 2: Table S1). The remaining 15 samples of the 770 CRC could not be analyzed due to insufficient DNA or technical reasons. Most of KRAS-mutated cases showed a mutation at codon 12.

(152 cases; 70.3%) and codon 13 (64 cases; 29.7%). KRAS mutations were associated with right-sided CRC (p = 0.0064).

Co-existence of KRAS and BRAF mutation

The clinico-pathological and molecular characteristics of the two CRC cases with co-existence of KRAS and BRAF mutations - “BRAF-1” and “BRAF-2” are summarized in Table 3. Both the patients were males with age > 40 years(47 years and 60 years); MSI-L/MSS type; histology subtype of adenocarcinomas with moderate differentiation; and Stage I cancer. Both these cases had mutation in codon 13 for KRAS gene and the BRAF gene showed mutation at V600E and V601E for BRAF-1 and BRAF-2 specimen respectively.

Microsatellite instability analysis

MSI analysis data was available in 741 of the 770 samples and the incidence of microsatellite instable (MSI-H), microsatellite low (MSI-L) and microsatellite stable (MSS) was 11.2%( 83/741), 18.6% (138/741) and 70.2% ( 520/741) respectively. The remaining 29 samples could not be analyzed due to insufficient DNA, lack of paired normal DNA or technical reasons.

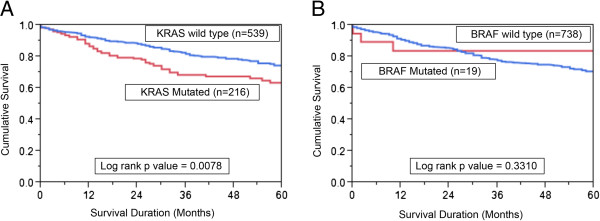

BRAF mutation, KRAS mutation, and overall survival

The prognostic significance of KRAS and BRAF mutation was analyzed with the use of the Kaplan–Meier method. Patients with KRAS mutation had poorer survival as compared to CRC with wild type KRAS gene (p = 0.0078) (Figure 2A). In the multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model (Additional file 3: Table S2) for multiple factors such as age, gender, AJCC stage, microsatellite instability and tumor differentiation, the relative risk was 1.75 for CRC with KRAS mutation(95% CI 1.26-2.42; p = 0.0011) and 6.70 for advanced AJCC stage(95% CI 4.78-9.31; p ≤ 0.0001). Thus, KRAS mutation was an independent prognostic marker for poor survival in CRC across all stages. We also assessed the overall survival of KRAS mutation at codon12 and codon13. Amongst the KRAS-mutated cases, mutation in codon 12 was associated with the worst survival (62.8%; p = 0.0230) compared with codon 13 mutations (64.7%) or absence of KRAS mutations (73.5%). BRAF mutation was not associated with any prognostic significance (p = 0.3310; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Impact of KRAS and BRAF mutations in CRC and the Kaplan–Meier. Survival analysis. (A) Colorectal cancer patients with KRAS mutations had reduced overall survival of 63.5% at 5 years compared with 73.5% without KRAS mutations (p = 0.0078). (B) In CRC patients, there was no significance in survival between BRAF mutated and non mutated cases. (p = 0.3310).

Discussion

Accumulating evidence implicates BRAF mutations to have diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic significance in CRC [10,19-22]. In our study, the BRAF-V600E mutation was identified in only 2.5% of all CRC, which is significantly lower than earlier reports of BRAF mutation in CRC worldwide (5-15%; [22-26]). The overall low frequency of the BRAF-V600E mutation and serrated adenomas in this unique ethnic group of Saudi colorectal cancer cases suggests a very small role of the BRAF gene in the development of CRC and raises some interesting future questions on the burden of familial colorectal cancers like Hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer cancer(HNPCC) syndrome in Saudi Arabia.

The reported frequency of BRAF mutations in different populations varies widely from a low incidence of 1% in Taiwan to 19.8% and 21.8% in Netherlands and USA respectively [22-25,27-40]. A lower frequency has been observed in most of the Asian population as is evident from the lowest BRAF mutation incidence of 1% in Taiwan where BRAF mutation was seen in 2/182 CRC. A similar low incidence was seen in China (3.8% and 7%) and Japan (4.7% and 6.7%). BRAF mutation was also observed at a lower rate of 5% in Israel [39]. Interestingly the frequency of the BRAF V600E mutation varies widely between population groups, both within single studies (5.8% in the Ashkenazi versus 3.2% in the non-Ashkenazi) and also between reports from different groups but within the same region/country [36,41]. The lower incidence of BRAF mutations in Saudi CRC patients could be due to a different ethnic populations with varied underlying genetic predisposition to BRAF-mutated tumors, role of environmental influences like diet, smoking and other unknown factors. Different methods used to detect gene mutation such as 454 next generation sequencing, Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing and melting curve analysis also influence the detection rate of a gene mutation [42]. An earlier study has highlighted the differing rates of BRAF mutation in distinct ancestral populations with a lower frequency observed in Asian population as compared to White and Black patients in their study [43].

Although BRAF mutations occur early in colorectal carcinogenesis and have been observed in colorectal adenomas, tumor progression needs additional acquired DNA microsatellite instability caused by hypermethylation of MLH1 in the setting of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) [12,44]. These precursor lesions that harbor BRAF mutation, microsatellite instability and CIMP phenotype have a distinct morphology and are termed serrated adenomas. A retrospective review of all the available biopsies of hyperplastic polyps and adenomas biopsies confirmed the presence of only one case that had a morphology consistent with serrated adenomas. Additional efforts to identify serrated adenomas from the FFPE archives of Department of Pathology confirmed the fact that serrated adenomas were exceedingly rare. We have analyzed CIMP in 500 CRC patients and have observed a very low frequency of CIMP of 4.8% (data not shown). In concordance with an earlier study we hypothesize that lack of a propensity for hypermethylation and other factors in Saudi CRC prevents the driver BRAF mutation in premalignant lesions to progress to full blown cancers [13]. Although smoking is one of the factors implicated in CIMP phenotype and the incidence of smoking in Saudi Arabia is quite high [45,46], the prevalence of BRAF mutations, CIMP and serrated adenomas in our study population was on the lower side. Moreover, the significantly lower incidence of BRAF mutations in our study suggests the existence of a possibly higher number of familial syndromes like HNPCC that are characterized by a virtual lack of BRAF abnormalities in colorectal cancers. A study is being conducted to determine the true incidence of HNPCC in Saudi Arabia. Presence of BRAF V600E mutation in CRC tumors that lacks the expression of MLH1 by IHC does not warrant further genetic testing and excludes the possibility of the presence of a germline mutation in mismatch repair (MMR) genes. This exquisite sensitivity of BRAF V600E somatic mutation for sporadic MSI has led to the development of an algorithm for screening of LS as a multistep diagnostic approach in several guidelines and recommendations [15,47]. Since a significant proportion of sporadic CRC get excluded, the use of BRAF V600E as a screening tool to identify sporadic MSI CRC tumors is highly cost effective [15,47,48]. Newer developments in the detection of BRAF V600E mutation in CRC by IHC have shown to have a comparable sensitivity and specificity as PCR testing [49]. After stringent validation of BRAF IHC in each lab, BRAF testing by IHC will prove to be a simple, economical, labor and time saving test that can be performed even in small biopsies that yield a small amount of DNA. Finally Weisenberger et al investigated CIMP in CRC and demonstrated that MSI-H CRC are either HNPCC or MSI-H and CIMP + with or without MLH1 methylation [50]. The authors concluded that CIMP + encompass almost all sporadic MSI-H CRC while MLH1 methylation constitute a part of, but not all CIMP + CRC tumors. Since BRAF mutations distinctly correlate with CIMP + CRC, BRAF testing could outperform MLH1 methylation in identifying sporadic MSI-H CRC tumors in the diagnostic approach of LS [50].

Emerging studies highlight the critical significance of the impact of BRAF mutations on colorectal research. Although there has been remarkable success in using BRAF inhibitors in melanomas with a response rate of over 80%, a lower response rate of about 10% is seen in CRCs [20]. A key mechanism causing resistance to BRAF inhibitors in CRC is upregulation of the EGFR pathway and a combination therapy with EGFR inhibitors and BRAF inhibitors might prove effective [20]. Dual synergism could guide strategies that aim to improve outcomes especially in patients who are refractory to initial lines of therapy.

In conclusion, we observed a very low incidence of CRC with BRAF mutations that showed a significant association with right sided tumors, CIMP high phenotype and microsatellite instability. Future work would be directed to establish an effective screening program to study the prevalence of HNPCC cases in Saudi Arabia and also try to understand the complex interaction between genetics and environmental factors that contribute to this low incidence of BRAF mutations in this region.

Consent

Waiver of consent was obtained for the study from Research Ethic committee under Project RAC 2080 030 on archival colorectal samples.

Competing interest

This manuscript has not been published earlier and the authors have declared no competing interest.

Authors’ contribution

PB, RB, SP & SB acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical support. MAR, MAH and KAO acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; technical support. AKS, NAS, FAD, HAM and SU acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content technical, or material support; study supervision. KSA study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

BRAF mutation and proliferation index as measured by Ki-67 IHC expression. Box Plot charts indicates the mean and SD of Ki-67 expression in two groups: The expression of Ki-67 in BRAF Positive (88.89 ± 12.78) and BRAF Negative (80.60 ± 25.30, p value 0.0162).

Correlation of KRAS Mutation with clinico-pathological parameters in colorectal carcinoma.

Univariate and Multivariate analysis of Kras Mutation using Cox Proportional Hazard Model.

Contributor Information

Abdul K Siraj, Email: asiraj@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Rong Bu, Email: rbu@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Sarita Prabhakaran, Email: sprabakaran@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Prashant Bavi, Email: prashant.bavi@gmail.com.

Shaham Beg, Email: bshaham@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Mohsen Al Hazmi, Email: alhazmi.md.phd@gmail.com.

Maha Al-Rasheed, Email: mrasheed@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Khadija Alobaisi, Email: kalobaisi@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Fouad Al-Dayel, Email: dayelf@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Hadeel AlManea, Email: halmanea@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Nasser Al-Sanea, Email: nsanea@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Shahab Uddin, Email: shahab@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Khawla S Al-Kuraya, Email: kkuraya@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Acknowledgment

We thank Valorie Balde, Padmanaban Annaiyappanaidu, Wael Haqqawi, Hassan Al Dossarie, for technical assistance, Lisa Devera, Mary Galvez and Zeeshan Qadri for data analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, (KACST).

References

- Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, Nakamura Y, White R, Smits AM, Bos JL. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instability in colorectal cancers. Nature. 1997;386:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, Meltzer SJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Fodde R, Ranzani GN, Srivastava S. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass JR, Iino H, Ruszkiewicz A, Painter D, Solomon MJ, Koorey DJ, Cohn D, Furlong KL, Walsh MD, Palazzo J, Edmonston TB, Fishel R, Young J, Leggett BA. Neoplastic progression occurs through mutator pathways in hyperplastic polyposis of the colorectum. Gut. 2000;47:43–49. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacu E, Mori Y, Sato F, Yin J, Olaru A, Sterian A, Xu Y, Wang S, Schulmann K, Berki A, Kan T, Abraham JM, Meltzer SJ. Activin type II receptor restoration in ACVR2-deficient colon cancer cells induces transforming growth factor-beta response pathway genes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7690–7696. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Balfour J, Bardelli A. Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1308–1324. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartore-Bianchi A, Martini M, Molinari F, Veronese S, Nichelatti M, Artale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Mazzucchelli L, Frattini M, Siena S, Bardelli A. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1851–1857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn CP, Zobell SD, Furtado LV, Baker CL, Samowitz WS. Frequency of KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:307–312. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Danielsen SA, Ahlquist T, Merok MA, Agesen TH, Vatn MH, Mala T, Sjo OH, Bakka A, Moberg I, Fetveit T, Mathisen O, Husby A, Sandvik O, Nesbakken A, Thiis-Evensen E, Lothe RA. DNA sequence profiles of the colorectal cancer critical gene set KRAS-BRAF-PIK3CA-PTEN-TP53 related to age at disease onset. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e13978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J. et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL, Spring KJ, Wynter CV, Walsh MD, Barker MA, Arnold S, McGivern A, Matsubara N, Tanaka N, Higuchi T, Young J, Jass JR, Leggett BA. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut. 2004;53:1137–1144. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velho S, Moutinho C, Cirnes L, Albuquerque C, Hamelin R, Schmitt F, Carneiro F, Oliveira C, Seruca R. BRAF, KRAS and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal serrated polyps and cancer: primary or secondary genetic events in colorectal carcinogenesis? BMC Cancer. 2008;8:255–260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Ruschoff J, Fishel R, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Hamelin R, Hamilton SR, Hiatt RA, Jass J, Lindblom A, Lynch HT, Peltomaki P, Ramsey SD, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Vasen HF, Hawk ET, Barrett JC, Freedman AN, Srivastava S. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261–268. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Laiho P, Ollikainen M, Pinto M, Wang L, French AJ, Westra J, Frebourg T, Espin E, Armengol M, Hamelin R, Yamamoto H, Hofstra RM, Seruca R, Lindblom A, Peltomaki P, Thibodeau SN, Aaltonen LA, Schwartz S Jr. BRAF screening as a low-cost effective strategy for simplifying HNPCC genetic testing. J Med Genet. 2004;41:664–668. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavi P, Prabhakaran SE, Abubaker J, Qadri Z, George T, Al-Sanea N, Abduljabbar A, Ashari LH, Alhomoud S, Al-Dayel F, Hussain AR, Uddin S, Al-Kuraya KS. Prognostic significance of TRAIL death receptors in Middle Eastern colorectal carcinomas and their correlation to oncogenic KRAS alterations. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:203–215. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abubaker J, Bavi P, Al-Haqawi W, Sultana M, Al-Harbi S, Al-Sanea N, Abduljabbar A, Ashari LH, Alhomoud S, Al-Dayel F, Uddin S, Al-Kuraya KS. Prognostic significance of alterations in KRAS isoforms KRAS-4A/4B and KRAS mutations in colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2009;219:435–445. doi: 10.1002/path.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavi P, Jehan Z, Bu R, Prabhakaran S, Al Sanea N, Al Dayel F, Al Assiri M, Al Halouly T, Sairafi R, Uddin S, Al Kuraya KS. ALK gene amplification is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2735–2743. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Niessen RC, Oliveira C, Alhopuro P, Moutinho C, Espin E, Armengol M, Sijmons RH, Kleibeuker JH, Seruca R, Aaltonen LA, Imai K, Yamamoto H, Schwartz S Jr, Hofstra RM. BRAF-V600E is not involved in the colorectal tumorigenesis of HNPCC in patients with functional MLH1 and MSH2 genes. Oncogene. 2005;24:3995–3998. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, Beijersbergen RL, Bardelli A, Bernards R. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan ZX, Wang XY, Qin QY, Chen DF, Zhong QH, Wang L, Wang JP. The prognostic role of BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer receiving anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino S, Shima K, Meyerhardt JA, McCleary NJ, Ng K, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Schaefer P, Whittom R, Hantel A, Benson AB 3rd, Spiegelman D, Goldberg RM, Bertagnolli MM, Fuchs CS. Predictive and prognostic roles of BRAF mutation in stage III colon cancer: results from intergroup trial CALGB 89803. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:890–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HT, Lu YY, An YX, Wang X, Zhao QC. KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in human colorectal cancer: relationship with metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1691–1697. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlobec I, Bihl MP, Schwarb H, Terracciano L, Lugli A. Clinicopathological and protein characterization of BRAF- and K-RAS-mutated colorectal cancer and implications for prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:367–380. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C, Burke JP, Kalady MF, Coffey JC. BRAF mutation is associated with distinct clinicopathological characteristics in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(12):e711–e718. doi: 10.1111/codi.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TJ, Hardingham JE, Lee CK, Weickhardt A, Townsend AR, Wrin JW, Chua A, Shivasami A, Cummins MM, Murone C, Tebbutt NC. Impact of KRAS and BRAF gene mutation status on outcomes from the phase III AGITG MAX trial of capecitabine alone or in combination with bevacizumab and mitomycin in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2675–2682. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Arena S, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Mazzucchelli L, Frattini M, Siena S, Bardelli A. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5705–5712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina-Sarasqueta A, van Lijnschoten G, Moerland E, Creemers GJ, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, van den Brule AJ. The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2396–2402. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh LL, Er TK, Chen CC, Hsieh JS, Chang JG, Liu TC. Characteristics and prevalence of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer by high-resolution melting analysis in Taiwanese population. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:1605–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalady MF, Dejulius KL, Sanchez JA, Jarrar A, Liu X, Manilich E, Skacel M, Church JM. BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with distinct clinical characteristics and worse prognosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:128–133. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823c08b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou JM, Wu MS, Shun CT, Chiu HM, Chen MJ, Chen CC, Wang HP, Lin JT, Liang JT. Mutations in BRAF correlate with poor survival of colorectal cancers in Chinese population. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1387–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modest DP, Jung A, Moosmann N, Laubender RP, Giessen C, Schulz C, Haas M, Neumann J, Boeck S, Kirchner T, Heinemann V, Stintzing S. The influence of KRAS and BRAF mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab-based first-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer: an analysis of the AIO KRK-0104-trial. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:980–986. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi R, Harada J, Tuul M, Zhao Y, Ando K, Saeki H, Oki E, Ohga T, Kitao H, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y. Prognostic relevance of KRAS and BRAF mutations in Japanese patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:1042–1048. doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, Elliott F, Daly CL, Meade AM, Taylor G, Barrett JH, Quirke P. KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5931–5937. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, Dietrich D, Biesmans B, Bodoky G, Barone C, Aranda E, Nordlinger B, Cisar L, Labianca R, Cunningham D, Van Cutsem E, Bosman F. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:466–474. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek LS, Herron CM, Greenson JK, Moreno V, Capella G, Rennert G, Gruber SB. Smoking, gender, and ethnicity predict somatic BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:838–843. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Albertsen H, Levin TR, Murtaugh MA, Wolff RK, Slattery ML. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6063–6069. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saridaki Z, Papadatos-Pastos D, Tzardi M, Mavroudis D, Bairaktari E, Arvanity H, Stathopoulos E, Georgoulias V, Souglakos J. BRAF mutations, microsatellite instability status and cyclin D1 expression predict metastatic colorectal patients’ outcome. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1762–1768. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilkin A, Niv Y, Nagasaka T, Morgenstern S, Levi Z, Fireman Z, Fuerst F, Goel A, Boland CR. Microsatellite instability, MLH1 promoter methylation, and BRAF mutation analysis in sporadic colorectal cancers of different ethnic groups in Israel. Cancer. 2009;115:760–769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota T, Ura T, Shibata N, Takahari D, Shitara K, Nomura M, Kondo C, Mizota A, Utsunomiya S, Muro K, Yatabe Y. BRAF mutation is a powerful prognostic factor in advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:856–862. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DR, Young JP, Simpson JA, Jenkins MA, Southey MC, Walsh MD, Buchanan DD, Barker MA, Haydon AM, Royce SG, Roberts A, Parry S, Hopper JL, Jass JJ, Giles GG. Ethnicity and risk for colorectal cancers showing somatic BRAF V600E mutation or CpG island methylator phenotype. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1774–1780. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altimari A, de Biase D, De Maglio G, Gruppioni E, Capizzi E, Degiovanni A, D’Errico A, Pession A, Pizzolitto S, Fiorentino M, Tallini G. 454 next generation-sequencing outperforms allele-specific PCR, Sanger sequencing, and pyrosequencing for routine KRAS mutation analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1057–1064. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S42369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna MC, Go C, Roden C, Jones RT, Pochanard P, Javed AY, Javed A, Mondal C, Palescandolo E, Van Hummelen P, Hatton C, Bass AJ, Chun SM, Na DC, Kim TI, Jang SJ, Osarogiagbon RU, Hahn WC, Meyerson M, Garraway LA, Macconaill LE. Colorectal cancers from distinct ancestral populations show variations in BRAF mutation frequency. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass JR, Young J, Leggett BA. Hyperplastic polyps and DNA microsatellite unstable cancers of the colorectum. Histopathology. 2000;37:295–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassiony MM. Smoking in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:876–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Ghobain MO, Al Moamary MS, Al Shehri SN, Al-Hajjaj MS. Prevalence and characteristics of cigarette smoking among 16 to 18 years old boys and girls in Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:137–140. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.82447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Version 2.2014. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf. Accessed 15th June, 2014.

- Palomaki GE, McClain MR, Melillo S, Hampel HL, Thibodeau SN. EGAPP supplementary evidence review: DNA testing strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2009;11:42–65. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818fa2db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capper D, Voigt A, Bozukova G, Ahadova A, Kickingereder P, Von Deimling A, Von Knebel Doeberitz M, Kloor M. BRAF V600E-specific immunohistochemistry for the exclusion of Lynch syndrome in MSI-H colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1624–1630. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, Kang GH, Widschwendter M, Weener D, Buchanan D, Koh H, Simms L, Barker M, Leggett B, Levine J, Kim M, French AJ, Thibodeau SN, Jass J, Haile R, Laird PW. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

BRAF mutation and proliferation index as measured by Ki-67 IHC expression. Box Plot charts indicates the mean and SD of Ki-67 expression in two groups: The expression of Ki-67 in BRAF Positive (88.89 ± 12.78) and BRAF Negative (80.60 ± 25.30, p value 0.0162).

Correlation of KRAS Mutation with clinico-pathological parameters in colorectal carcinoma.

Univariate and Multivariate analysis of Kras Mutation using Cox Proportional Hazard Model.