Abstract

Adipose tissue dysfunction may be a central factor in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gene expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue in PCOS and its relation to metabolic and endocrine features of the syndrome have been fragmentarily investigated. The aim was to assess in subcutaneous adipose tissue the expression of genes potentially associated with adipose tissue dysfunction and to explore their relation to features of the syndrome. Twenty-one women with PCOS (body mass index [BMI] 18.2–33.4 kg/m2) and 21 controls (BMI 19.2–31.7 kg/m2) were matched pair-wise for age, body weight, and BMI. Tissue biopsies were obtained to measure mRNA expression of 44 genes (TaqMan Low Density Array). Differential expression levels were correlated with BMI, glucose infusion rate (GIR), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), and sex steroids. In PCOS, expression of adiponectin receptor 2 (ADIPOR2), LPL, and twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1) was decreased, while expression of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and heme oxygenase (decycling 1) (HMOX1) was increased. TWIST1 and HMOX1, both novel adipokines, correlated with BMI and GIR. After BMI adjustment, LPL and ADIPOR2 expression correlated with plasma estradiol, and CCL2 expression correlated with GIR, in all women. We conclude that adipose tissue mRNA expression differed in PCOS women and controls and that two novel adipokines, TWIST1 and HMOX1, together with adiponectin, LPL, and CCL2, and their downstream pathways merit further investigation.

Keywords: adiponectin receptor 2 (ADIPOR2), adipose tissue, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), gene expression, heme oxygenase (decycling 1) (HMOX1), insulin sensitivity, lipoprotein lipase (LPL), PCOS, twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1)

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is associated not only with endocrine abnormalities but also with insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, chronic low-grade inflammation, and disturbances of coagulation and fibrinolysis.1-3 Consequently, PCOS increases the risk for type 2 diabetes and possibly cardiovascular disease.1 Insulin resistance is thought to be a key pathophysiological feature that contributes to both reproductive and other metabolic disturbances in PCOS. However, the insulin resistance is only partly due to the high prevalence of obesity in women with the syndrome and is greater than that determined by their adiposity.4

Adipose tissue dysfunction is emerging as an important mechanism by which adipose tissue contributes to systemic insulin resistance and metabolic disease. We recently stressed the role of aberrant adipose tissue morphology and function in the pathogenesis/maintenance of insulin resistance in PCOS.4 Enlarged fat cells and reduced serum adiponectin, together with a large waistline, were the variables most strongly associated with insulin sensitivity in women with PCOS.4

Other features of adipose tissue, such as lipid metabolism (lipolysis, lipoprotein lipase [LPL] activity) and insulin action, have been reported to be aberrant in women with PCOS.4-6 Further, disturbed secretion of several adipokines may contribute to insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk.7-12 Gene expression profiles in omental fat from morbidly obese and in subcutaneous fat from nonobese women with and without PCOS revealed differences in the expression of genes encoding components of several biological pathways related to insulin and Wnt signaling, inflammation, immune function, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress.13,14 Thus, adipose tissue dysfunction may negatively affect the metabolic health of women with PCOS and thereby increase their risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. However, the key factors in adipose tissue that are involved and their regional contribution have not been established.

Since dysfunctional adipose tissue is increasingly considered to be important in the metabolic disturbances in PCOS,4-6,12,15 we assessed, in subcutaneous adipose tissue, the expression of genes potentially involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS and adipose tissue dysfunction. We also explored the relation between gene expression and the cardinal features of the syndrome, i.e., body mass index (BMI), glucose infusion rate (GIR), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), testosterone, and estradiol. Particular focus was given to pair-wise matching of women with PCOS and controls for age, body weight, and BMI.

Results

Subject matching

The age range was 21–37 y in women with PCOS and 22–35 y in controls. The age difference (control vs. PCOS) ranged from –4 to 3 y (mean, –1 ± 2.36 y). Body weight range was 55.2–96.0 kg in women with PCOS and 54.1–99.2 kg in controls. The body weight difference (control vs. PCOS) ranged from –4.9 to 4.6 kg (mean, 0.0 ± 2.63 kg). The BMI was 18.2–33.4 kg/m2 in women with PCOS and 19.2–31.7 kg/m2 in controls. The BMI difference (control vs. PCOS) ranged from –1.79 to 1.48 kg/m2 (mean, –0.25 ± 0.94 kg/m2). The proportion of overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) was 38%. All 21 matched pairs met the criteria for age (± 5 y), weight (± 5 kg), and BMI (± 2 kg/m2). However, the paired statistics revealed a significant difference in age (29.0 ± 4.2 vs. 27.6 ± 3.5; PCOS vs. controls, P = 0.03, Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of women with PCOS and controls pair-wise matched for age, weight, and body mass index (BMI).

| Variable | PCOS (n = 21) | Controls (n = 21) | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 29.0 ± 4.2 | 27.6 ± 3.5 | 0.031 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.6 ± 3.9 | 24.3 ± 3.5 | 0.433 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.2 ± 11.3 | 71.3 ± 11.5 | 0.886 |

| Glucose disposal rate (mg kg−1 min−1) | 10.9 ± 2.6 | 12.6 ± 3.7 | 0.046 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 48.0 ± 24.6 | 69.1 ± 30.5 | 0.030 |

| Testosterone (nmol/L) | 1.91 ± 0.57 | 0.75 ± 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Estradiol (pmol/L) | 236 ± 135 | 136 ± 52 | 0.002 |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD; aPaired t test; SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin

Subject characteristics

In this study we included 42 controls and PCOS women pair-matched for age, weight and BMI (Table 1). As previously reported, PCOS women are insulin resistant (lower GIR) and have lower circulating levels of SHBG, and higher levels of testosterone and estradiol than controls (Table 1),2 all cardinal features of PCOS.

Adipose tissue gene expression

We and others have shown that women with PCOS have dysfunctional adipose tissue.4-7,13,14,16 To get further insight into the role of adipose tissue in PCOS, we measured in adipose tissue the mRNA expression of genes related to adipokines, inflammation, lipid metabolism, adipogenesis, insulin sensitivity, oxidative stress, and steroidogenesis. In women with PCOS, ADIPOR2, LPL, and TWIST1 were expressed at significantly lower levels, and CCL2 (also known as monocyte chemotactic protein-1) and HMOX1 were expressed at higher levels, than in controls (Fig. 1). All nonsignificant genes are shown in Table S2.

Figure 1. Significantly expressed genes in women with PCOS relative to controls in subcutaneous adipose tissue. Data are normalized to the controls and each line represent geometrical mean. Log-transformed RQ values were compared by paired t test; CLN3 and LRP10 severed as reference genes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Correlations

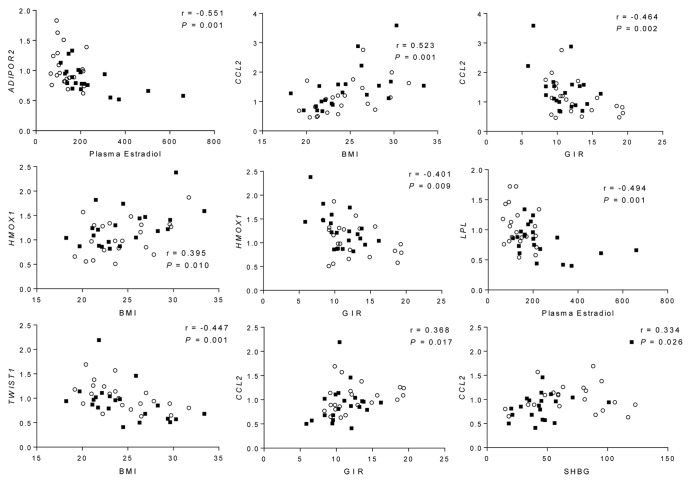

Next, we investigated whether altered mRNA expression of ADIPOR2, CCL2, HMOX1, LPL, and TWIST1 correlated with BMI and clinical variables shown to differ between women with PCOS and controls (Fig. 2). These variables include insulin sensitivity (GIR), SHBG, and sex steroids including testosterone and estradiol.2 Correlations between mRNA expression and clinical variables were based on all women in the cohort.

Figure 2. Correlations between mRNA expression in adipose tissue and clinical variables in all women. Filled squares, PCOS; circles, controls. BMI, body mass index; GIR, glucose infusion rate.

Circulating estradiol correlated with ADIPOR2 and LPL inversely and independently of BMI (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations and partial correlations, adjusted for body mass index (BMI), between mRNA expression in adipose tissue and clinical variables in all women.

| Clinical variable | ADIPOR2 | CCL2 | HMOX1 | LPL | TWIST1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.225, P = 0.153 | 0.523, P = 0.001 | 0.395, P = 0.010 | 0.180, P = 0.254 | −0.477, P = 0.001 |

| GIR (mg kg−1 min−1) | −0.264, P = 0.091 | −0.464, P = 0.002 | −0.401, P = 0.009 | −0.174, P = 0.270 | 0.368, P = 0.017 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | −0.148, P = 0.349 | −0.250, P = 0.111 | −0.278, P = 0.075 | −0.166, P = 0.293 | 0.344, P = 0.026 |

| Testosterone (ng/mL) | −0.145, P = 0.358 | −0.205, P = 0.192 | −0.230, P = 0.143 | −0.080, P = 0.617 | −0.267, P = 0.087 |

| Estradiol (pmol/L) | −0.551, P = 0.001 | −0.041, P = 0.796 | 0.017, P = 0.917 | −0.494, P = 0.001 | 0.018, P = 0.912 |

| BMI adjusted | |||||

| GIR (mg kg−1 min−1) | −0.190, P = 0.235 | −0.308, P = 0.050 | −0.276, P = 0.080 | −0.108, P = 0.501 | 0.202, P = 0.205 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | −0.056, P = 0.727 | −0.024, P = 0.880 | −0.125, P = 0.435 | −0.098, P = 0.541 | 0.169, P = 0.291 |

| Testosterone (ng/mL) | −0.205, P = 0.198 | 0.108, P = 0.502 | 0.159, P = 0.321 | −0.124, P = 0.438 | −0.189, P = 0.238 |

| Estradiol (pmol/L) | −0.517, P = 0.001 | 0.189, P = 0.237 | 0.188, P = 0.239 | −0.467, P = 0.002 | −0.191, P = 0.232 |

Pearson correlation. GIR, glucose infusion rate; SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin.

CCL2 correlated positively with BMI and inversely with GIR (Fig. 2). The correlation with GIR was significant also after adjustment for BMI (Table 2).

HMOX1 correlated positively with BMI, and inversely with GIR (Fig. 2). The significance of these correlations was lost after adjustment for BMI (Table 2).

TWIST1 correlated inversely with BMI and positively with GIR and SHBG (Fig. 2). The significance of these correlations was lost after adjustment for BMI (Table 2).

Discussion

We investigated adipose tissue expression of genes potentially involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS and its dysfunctional adipose tissue. Of 44 selected genes related to insulin sensitivity, inflammation, lipid metabolism, adipogenesis, oxidative stress, steroidogenesis, and adipokines, we found that ADIPOR2, LPL, and TWIST1 were expressed at lower levels, and CCL2 and HMOX1 at higher levels, in subcutaneous adipose tissue from women with PCOS than in controls matched pair-wise for age, weight, and BMI. Expression of ADIPOR2 and LPL correlated inversely with serum estradiol and CCL2 with GIR, independent of BMI.

Insulin resistance is a key factor in the pathogenesis of PCOS. In addition to clear evidence of intrinsic defects in insulin signaling in skeletal muscle, similar defects in insulin signaling have also been described in adipose tissue in PCOS, but data are limited.5 TWIST1 expression, which is predominantly found in adipocytes, is highest in samples from nonobese subjects with hyperplastic adipose tissue and lowest in obese subjects with hypertrophic adipose tissue.17 This is in line with the inverse correlation between TWIST1 expression and BMI in both controls and PCOS women. We showed for the first time that adipose tissue expression of TWIST1 is lower in insulin-resistant women with PCOS than in controls. And, there was a positive correlation of TWIST1 expression with GIR and SHBG, but this did not remain significant after adjustment for BMI. This suggests an association with fatty acid oxidation in PCOS since Twist1 may, in contrast to findings in mice, be a positive regulator of fatty acid oxidation in human white adipocytes.17 Moreover, Twist1 knockdown accentuates the pro-inflammatory effects of TNF-α, suggesting that Twist1 protects against adipose inflammation.17 Our finding that TWIST1 expression correlates inversely with BMI and positively with GIR is in line with a reported association between low expression of TWIST1 in adipose tissue and an adverse metabolic profile.17

Increased oxidative stress in fat is a key mechanism of obesity-related insulin resistance.18 Oxidative stress impairs glucose uptake in both muscle and fat.19,20 Proteomic and genomic studies have highlighted the role of oxidative stress in omental fat from obese PCOS women.13,16 It is not known whether subcutaneous fat is altered in normal-weight PCOS women as well. HMOX1 has been implicated as a new adipokine known to reduce oxidative stress. In contrast to a recent study,21 we found that HMOX1 mRNA expression was higher, instead of lower, in women with PCOS and correlated with a high BMI, and insulin resistance. Although there was a tendency (P = 0.080), this correlation did not remain significant after adjustment for BMI. However, in line with our results circulating levels and adipose tissue HMOX1 expression are elevated in obese subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes.22,23 HMOX1 is induced by oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators, and it is proposed that upregulation of Hmox1 may have anti-inflammatory properties and protect cells from oxidative damage.24,25 Increased HMOX1 expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue in women with PCOS may reflect a compensatory/protective mechanism to reduce an oxidative and inflammatory status in adipose tissue.

Women with PCOS seem to have disturbances in lipid metabolism in subcutaneous adipose tissue. The lipolytic effect of catecholamines in subcutaneous adipose tissue is blunted, which can be attributed to decreased amounts of β2-adrenergic receptors (ADRB2) and hormone-sensitive lipase (LIPE) protein.6 We recently reported that LPL activity in adipose tissue is lower in PCOS women than controls.4 Although the expression of genes related to lipolysis and lipid metabolism (e.g., ADRB2, ADRA2A, FABP4, and LIPE) did not differ in PCOS women and controls in the present study, PCOS women had lower LPL expression in adipose tissue than controls, consistent with our previous findings.4 Both androgens and estrogens have been reported to inhibit adipose tissue LPL activity.26,27 In support of this, adipose tissue gene expression of LPL correlated negatively with plasma estradiol, and the correlation remained significant after adjustment for BMI.

Systemic low-grade inflammation, characterized by increased accumulation of macrophages and release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in adipose tissue, has been suggested to contribute to insulin resistance and be a hallmark of obesity. Circulating levels of several markers of inflammation are elevated in women with PCOS, but whether the elevations are independent of obesity is debated.28 We recently showed that macrophage density in subcutaneous adipose tissue and circulating inflammatory markers do not differ in PCOS women and controls after adjustment for age, weight, and BMI.3,4 Further, a recent study concluded that obesity rather than PCOS per se seems to be the main determinant of increased inflammatory markers in adipose tissue.29 Indeed, we found that the genes related to immune and inflammatory response (e.g., CD68, IL6, IL8, SAA2, and TNF) were expressed at similar levels in adipose tissue of women with and without PCOS. However, expression of CCL2, which encodes a chemokine that attracts macrophages and other immune cells, was significantly upregulated in adipose tissue from PCOS women. And, a recent study showed that chemokines and cytokines, including CCL2, were paradoxically expressed at higher levels in adipose tissue from nonobese PCOS women than controls.14 We found that high CCL2 expression correlated inversely, and independently of BMI, with GIR. This is in line with the association between low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance.30 It is still unclear whether PCOS is associated with a systemic proinflammatory state independently of obesity and whether adipose tissue plays a role in it.

Dysregulation of adipokine production and secretion from adipose tissue may contribute to several cardinal and metabolic features of PCOS.31 Women with PCOS have lower circulating levels of adiponectin,4,32 and subcutaneous adipose tissue production of adiponectin is considered to be the main contributor to the circulating levels. However, studies on ADIPOQ expression in adipose tissue of women with PCOS have been inconsistent, finding either lower expression than in controls8 or no difference from controls.9,33-35 Although expression of ADIPOQ expression and other adipokines (e.g., LCN2, LEP, LPIN1, RBP4, and SERPINE1) did not differ in PCOS women and controls, expression of ADIPOR2, one of two cell membrane adiponectin receptors, was decreased in women with PCOS. This finding is in agreement with a previous small study in which mRNA expression of ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2 in omental adipose tissue was lower in nonobese women with PCOS than in age- and BMI-matched controls.34 However, in another small study, expression of ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2 mRNA in subcutaneous and omental fat was higher in PCOS women than in controls.36 In the present study, ADIPOR2 expression correlated positively, and independently of BMI, with plasma estradiol.

In contrast to earlier findings,13,14 we did not observe any significant difference in adipogenic transcription factors and markers of undifferentiated adipocytes (e.g., CEBPA, CEBPB, DLK1, PPARG, SREBF1, and WNT10B) and no differences in the expression of enzymes and receptors involved in steroidogenesis (e.g., AR, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, CYP19A1, ESR1, and SRD5A2) suggesting a normal adipogenesis and steroidogenesis in the subcutaneous adipose tissue in our cohort. However, we investigated only mRNA expression, not protein expression or enzyme activity. Thus, further studies are needed to elucidate the contribution of imbalanced adipogenesis and steroidogenesis to the pathophysiology of PCOS. In selecting the genes to investigate, we used a hypothesis-driven approach, whereas previous genomic and proteomic studies have used a discovery-driven approach. This difference can partly explain the discrepancies between our studies. Furthermore, despite their insulin resistance, women with PCOS in the present study had a relatively healthy metabolic profile, with no hypertension, lipid disturbances, or evident visceral adiposity.

Surprisingly few of the genes we investigated were differently expressed in subcutaneous adipose tissue from women with and without PCOS. However, previous microarray analyses of >14 500 genes in subcutaneous and omental adipose tissue from nonobese and obese PCOS women and controls reported differential expression of fewer than 100 genes.13,14 Commonly altered genes in these studies included those involved in inflammation, lipid metabolism, and Wnt signaling.

The main strengths of this study are the inclusion of untreated, well-characterized normal weight and overweight women with PCOS and the pair-wise matching by age, weight, and BMI to healthy controls. Further, we only included women with PCOS who fulfilled all three diagnostic criteria for the syndrome,37 resulting in a more homogenous study group. The majority of the genes in the present study have not previously been investigated in adipose tissue of PCOS women. Moreover, we use gold-standard techniques for measurements of circulating sex steroids and whole-body insulin sensitivity.2,4 However, a limitation of this study is relatively small numbers of patients and controls. Furthermore, we only examined mRNA expression, so our findings must be interpreted cautiously, as they might not be transferable to protein level.

In conclusion, PCOS women had significant differences from controls in mRNA expression in adipose tissue. The role of two novel adipokines TWIST1 and HMOX1, together with adiponectin, LPL, and CCL2, and their downstream pathways merit further investigation.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Subjects

All participants in the study were selected from premenopausal women with (n = 74) and without (n = 31) PCOS who were recruited by local advertising as described.2-4 To be included, women with PCOS had to (1) meet all three Rotterdam criteria for the syndrome (PCO morphology, hyperandrogenism, and menstrual irregularities),37 so as to reduce the metabolic heterogeneity associated with multiple phenotypic subgroups,38 and (2) be matched with a control woman by age (± 5 y), body weight (± 5 kg), and BMI (± 2 kg/m2). Twenty-one matched pairs were included and their clinical characteristics, as previously described,2-4 are shown in Table 1.

PCO morphology was confirmed by transvaginal sonography (12 or more follicles 2–9 mm in diameter or >10 mL in volume, in at least one ovary). Clinical signs of hyperandrogenism were defined as hirsutism (Ferriman–Gallwey score ≥ 8) and/or acne. Menstrual irregularities were defined as oligomenorrhea (intermenstrual interval >35 d and <8 cycles in the past year) or amenorrhea (absent menstrual bleeding or none in the past 90 d). All control women were eumenorrheic, had ultrasound-confirmed normal ovarian morphology, and had no signs of hyperandrogenism.

Exclusion criteria for all women were age <18 or >37 y, pharmacological treatment within 12 wks, breast feeding within 24 wk, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus or other endocrine disorders. All study subjects gave oral and written consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, University of Gothenburg. The Clinical Trials Government Identifier number is NCT00484705.

Study design

All examinations, including adipose tissue sampling, were performed in the morning after an overnight fast, as described.4 Since women with PCOS had oligo/amenorrhea, the examination day was chosen independently of cycle day. Controls were examined during the early follicular phase (days 1–7 of the cycle). A needle biopsy of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue was obtained under local anesthesia two-thirds of the distance from the iliac crest to the umbilicus.4 Part of the biopsy was immediately snap frozen for RNA extraction. Anthropometry, adipose tissue volumes, insulin sensitivity, adipocyte volume, LPL activity, and blood chemistry were analyzed as described.2-4

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Approximately 500 mg of snap-frozen adipose tissue was homogenized in QIAzol Lysis Reagent, supplied with the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Midi kit (Qiagen, 75842), using the TissueLyser (Qiagen, 85300). Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Lipid Tissue Midi kit and MaXtract High-density tubes according to manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, 75842 and 129065). RNA concentration and purity were evaluated with a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nano-Drop Technologies) and RNA integrity was verified with an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 and the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies, G2940CA and 5067-1511). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with Superscript VILO according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, 11754-250).

Gene expression

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with custom TaqMan gene expression array micro fluid cards (Life Technologies, Table S1). Samples were run in singletons, and the amount of cDNA in each loading port was equivalent to 100 ng of mRNA. The arrays were run according to the manufacturer’s protocol with an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System and ABI Prism 7900HT SDS software version 2.4 (Applied Biosystem).

Candidate reference genes (RN18S1, PPIA, LRP10, and CLN3) were validated with NormFinder and GeNorm algorithms and GenEx software (MultiD Analyses). Based on the results from these algorithms the combination of CLN3 and LRP10 was used as the reference control. Gene expression values were calculated with the ΔΔCq method (i.e., RQ = 2−ΔΔCq).39

Statistics

Paired t tests were used to compare mRNA levels and clinical variables between matched cases and controls. mRNA expression in controls was set to 1 to calculate fold changes in women with PCOS. Correlation analyses were performed with Pearson correlation, and partial correlation adjusted for BMI on the whole co-hort. RQ values were log-transformed and clinical variables were transformed as described.4 P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 for Windows (SPSS).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

For the use of technical equipment and support we thank the Genomics Core Facility at the Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, which was funded by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Financial Support

This study was financed by grants from the Swedish Research Council (K2012-55X-15276-08-3), Jane and Dan Olsson Foundations, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Swedish federal government under the LUA/ALF agreement (ALFGBG-136481) and the Regional Research and Development agreement (VGFOUREG-5171, -11296, and -7861).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ADIPOR

adiponectin receptor

- ADRB2

β2-adrenergic receptors

- BMI

body mass index

- CCL2

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- GIR

glucose infusion rate

- HMOX1

heme oxygenase (decycling 1)

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

- SHBG

sex hormone binding globulin

- TWIST1

twist-related protein 1

References

- 1.Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:347–63. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stener-Victorin E, Holm G, Labrie F, Nilsson L, Janson PO, Ohlsson C. Are there any sensitive and specific sex steroid markers for polycystic ovary syndrome? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:810–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannerås-Holm L, Baghaei F, Holm G, Janson PO, Ohlsson C, Lönn M, Stener-Victorin E. Coagulation and fibrinolytic disturbances in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1068–76. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannerås-Holm L, Leonhardt H, Kullberg J, Jennische E, Odén A, Holm G, Hellström M, Lönn L, Olivecrona G, Stener-Victorin E, et al. Adipose tissue has aberrant morphology and function in PCOS: enlarged adipocytes and low serum adiponectin, but not circulating sex steroids, are strongly associated with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E304–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corbould A. Insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue in polycystic ovary syndrome: are the molecular mechanisms distinct from type 2 diabetes? Panminerva Med. 2008;50:279–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arner P. Effects of testosterone on fat cell lipolysis. Species differences and possible role in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Biochimie. 2005;87:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmina E, Bucchieri S, Mansueto P, Rini G, Ferin M, Lobo RA. Circulating levels of adipose products and differences in fat distribution in the ovulatory and anovulatory phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(Suppl):1332–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmina E, Chu MC, Moran C, Tortoriello D, Vardhana P, Tena G, Preciado R, Lobo R. Subcutaneous and omental fat expression of adiponectin and leptin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:642–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor A, Phelan N, Tun TK, Boran G, Gibney J, Roche HM. High-molecular-weight adiponectin is selectively reduced in women with polycystic ovary syndrome independent of body mass index and severity of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1378–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mlinar B, Pfeifer M, Vrtacnik-Bokal E, Jensterle M, Marc J. Decreased lipin 1 beta expression in visceral adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:833–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan BK, Chen J, Lehnert H, Kennedy R, Randeva HS. Raised serum, adipocyte, and adipose tissue retinol-binding protein 4 in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome: effects of gonadal and adrenal steroids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2764–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villa J, Pratley RE. Adipose tissue dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11:179–84. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortón M, Botella-Carretero JI, Benguría A, Villuendas G, Zaballos A, San Millán JL, Escobar-Morreale HF, Peral B. Differential gene expression profile in omental adipose tissue in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:328–37. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chazenbalk G, Chen Y-H, Heneidi S, Lee J-M, Pall M, Chen Y-DI, Azziz R. Abnormal expression of genes involved in inflammation, lipid metabolism, and Wnt signaling in the adipose tissue of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E765–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildiz BO, Azziz R, Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Ovarian and adipose tissue dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: report of the 4th special scientific meeting of the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:690–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortón M, Botella-Carretero JI, López JA, Camafeita E, San Millán JL, Escobar-Morreale HF, Peral B. Proteomic analysis of human omental adipose tissue in the polycystic ovary syndrome using two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:651–61. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettersson AT, Mejhert N, Jernås M, Carlsson LMS, Dahlman I, Laurencikiene J, Arner P, Rydén M. Twist1 in human white adipose tissue and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:133–41. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudich A, Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Hemi R, Kanety H, Bashan N. Prolonged oxidative stress impairs insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1562–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.10.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maddux BA, See W, Lawrence JC, Jr., Goldfine AL, Goldfine ID, Evans JL. Protection against oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance in rat L6 muscle cells by mircomolar concentrations of α-lipoic acid. Diabetes. 2001;50:404–10. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seow K-M, Lin Y-H, Hwang J-L, Wang P-H, Ho L-T, Lin Y-H, Juan C-C. Expression levels of haem oxygenase-1 in the omental adipose tissue and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:431–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehr S, Hartwig S, Lamers D, Famulla S, Müller S, Hanisch FG, Cuvelier C, Ruige J, Eckardt K, Ouwens DM, et al. Identification and validation of novel adipokines released from primary human adipocytes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:010504. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao W, Song F, Li X, Rong S, Yang W, Zhang M, Yao P, Hao L, Yang N, Hu FB, et al. Plasma heme oxygenase-1 concentration is elevated in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ndisang JF. Role of heme oxygenase in inflammation, insulin-signalling, diabetes and obesity. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:359732. doi: 10.1155/2010/359732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen SB, Kristensen K, Hermann PA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Richelsen B. Estrogen controls lipolysis by up-regulating alpha2A-adrenergic receptors directly in human adipose tissue through the estrogen receptor alpha. Implications for the female fat distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1869–78. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blouin K, Nadeau M, Perreault M, Veilleux A, Drolet R, Marceau P, Mailloux J, Luu-The V, Tchernof A. Effects of androgens on adipocyte differentiation and adipose tissue explant metabolism in men and women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72:176–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Escobar-Morreale HF, Luque-Ramírez M, González F. Circulating inflammatory markers in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1048–58, e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindholm A, Blomquist C, Bixo M, Dahlbom I, Hansson T, Sundström Poromaa I, Burén J. No difference in markers of adipose tissue inflammation between overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome and weight-matched controls. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1478–85. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauner H. Secretory factors from human adipose tissue and their functional role. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:163–9. doi: 10.1079/PNS2005428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Farmakiotis D, Georgopoulos NA, Katsikis I, Tarlatzis BC, Papadimas I, Panidis D. Adiponectin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:297–307. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lecke SB, Mattei F, Morsch DM, Spritzer PM. Abdominal subcutaneous fat gene expression and circulating levels of leptin and adiponectin in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2044–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seow KM, Tsai YL, Juan CC, Lin YH, Hwang JL, Ho LT. Omental fat expression of adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in non-obese women with PCOS: a preliminary study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19:577–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fog Svendsen P, Christiansen M, Hedley PL, Nilas L, Bonlokke Pedersen S, Madsbad S. Adipose expression of adipocytokines in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan BK, Chen J, Digby JE, Keay SD, Kennedy CR, Randeva HS. Upregulation of adiponectin receptor 1 and 2 mRNA and protein in adipose tissue and adipocytes in insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2723–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moran L, Teede H. Metabolic features of the reproductive phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:477–88. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Δ Δ C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.