Abstract

Resection of skull base lesions has always been riddled with problems like inadequate access, proximity to major vessels, dural tears, cranial nerve damage, and infection. Understanding the modular concept of the facial skeleton has led to the development of transfacial swing osteotomies that facilitates resection in a difficult area with minimal morbidity and excellent cosmetic results. In spite of the current trend toward endonasal endoscopic management of skull base tumors, our series presents nine cases of diverse extensive skull base lesions, 33% of which were recurrent. These cases were approached through different transfacial swing osteotomies through the mandible, a midfacial swing, or a zygomaticotemporal osteotomy as dictated by the three-dimensional spatial location of the lesion, and its extent and proximity to vital structures. Access osteotomies ensured complete removal and good results through the most direct and safe route and good vascular control. This reiterated the fact that transfacial approaches still hold a special place in the management of extensive skull base lesions.

Keywords: skull base lesions, transfacial access osteotomies, transfacial swing approaches

Introduction

The heterogenicity of tissues of the skull base makes it a bed for a wide spectrum of benign and malignant lesions with variable prognoses. 1 Problems when resecting these lesions are infection, hematoma, proximity to major vessels, cerebrospinal fluid leak, cranial nerve damage, and, most importantly, difficulty in gaining safe, quick, and complete access to the lesion. The regular transfacial approaches include transnasal, transeptal, transsphenoidal, and intraoral (Le Fort 1) approaches. These approaches have limitations because the access here is through a small window with limited surgical field that allows removal of only small tumors and makes control of bleeding venous sinuses and epidural vessels difficult. 2 This led to the advent of transfacial swing approaches that are distinctive procedures where a portion of the orbit, zygoma, nasal bones, maxilla, and mandible were osteotomized, hinged, and swung to provide improved access to the skull base and parapharyngeal region. Von Langenbeck in 1859 preformed horizontal osteotomy in maxilla to access nasopharyngeal lesions. Kocher modified Langenbeck's technique by dividing the down fractured maxilla in the midline to approach the pituitary fossa. 3

This was the beginning of access osteotomies. It took over a century to receive and add more techniques, which include both intraoral and transfacial osteoplastic flaps to offer safe and adequate approach for complete resection of lesions involving anatomically compromised areas like the cranial base and parapharyngeal space. The last decade has witnessed an evolution toward the use of minimal access endoscopic techniques in nearly every surgical specialty. This technique provides access and visualization through the narrowest practical corridor with minimal disruption of normal tissues. Although a completely endoscopic approach is less invasive than a conventional open approach, oncologic principles of gross tumor excision with negative margins still remains the mainstay in the selection of the appropriate approach.

This article discusses the general principles of transfacial swing osteotomies and presents a series of nine cases of varied skull base lesions that further reiterate the heterogenicity of pathologies involving this area. Due to the size of the pathologies and recurrent nature (3 of 9 cases [33%]), transfacial swing osteotomy was considered the most appropriate treatment paradigm to ensure total resection of the lesion with the least functional and aesthetic morbidity.

Pathologies around the Skull Base

Although a broad spectrum of extracranial, junctional, and intracranial pathologies occur within a relatively small area surrounding the sphenoid bone, the complexity of this bone and the multiple structures that course through and surround it necessitate the use of different approaches depending on the exact anatomical location. 4

These are some of the pathologies that arise extracranially and may extend intracranially:

Cutaneous: basal and squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma

Orbital: neuroblastoma, optic nerve glioma, rhabdomyosarcoma

Paranasal and nasal cavities: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma

Salivary gland tumors: adenocarcinoma and mucoepidermoid tumors

Others: esthesioneuroblastoma, nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, and sarcoma

The pathologies that arise from cranial base and extend intra- or extracranially are chordoma, osteoma, fibrous dysplasia, chondroma, fibrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Those that arise intracranially and may extend extracranially are meningioma and neurofibroma. 5

Principles of Transfacial Swing

Transfacial swing is based on the premise that the craniofacial skeleton is a series of interconnecting modules that allow both independent and conjoined mobilization. Modules chosen for mobilization are case dependent. Zygoma, nasal bones, maxilla, or mandible can be osteotomized and swung pedicled onto overlying soft tissue unilaterally or bilaterally to provide a path of access. This also provides more direct unhindered and wider access to lesions lying in inaccessible areas of skull base and intracranial pathology without much traction on the brainstem or cranial nerves.

Types of Access Osteotomies

Based on the path chosen and bones mobilized, transfacial swing osteotomies can be classified as follows:

-

Transmandibular:

Labiomandibulotomy (lip split mandibular swing approach): central approach

Modified midline mandibulotomy (Attia approach)

Lateral osteotomies of the mandible without lip split

-

Transmaxillary:

Le Fort I osteotomy with or without soft palate split

Hemimaxillotomy: palatal mucosa pedicled

Hemimaxillotomy: cheek pedicled

Zygomaticotemporal approach

Fronto-orbital (glabellar) approach

Combination approaches: zygomaticomaxillary, nasomaxillary, nasozygomaticomaxillary

Patients and Methods

This article presents nine cases, six of which underwent a midfacial swing pedicled to cheek flap for retromaxillary and nasopharyngeal lesions involving the infratemporal region and lateral skull base. One patient underwent a zygomaticotemporal osteotomy for a lesion involving the infratemporal region and lateral skull base. Two patients underwent a transmandibular lateral approach for deep lobe parotid tumors involving the parapharyngeal space and extending up to involve the lateral skull base.

All patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary team composed of a neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist, maxillofacial surgeon, and radiologist. Extensive clinical and radiologic assessments were performed in all cases including:

History: duration, increase in size, disturbed/loss of function, neurologic deficit involving cranial nerve (I–XII)

Physical examination included detailed attention to cranial nerves, orbits, and upper digestive tract

Radiologic work-up included computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to clarify the extent of the tumor. Although CT was superior for defining bony planes and potential invasion, MRI provided invaluable information regarding soft tissue planes, perineural spread, and brain invasion.

Angiography (CTA/MRA) was done in select tumors that were highly vascular and needed embolization and a clear delineation of feeder vessels.

The ideal surgical approach was decided based on tumor size, anatomical location, proximity to vital structures, and possibility of resectability. 6 7 All surgeries were undertaken under nasoendotracheal intubation.

Surgical Techniques

Midfacial Swing Pedicled to Cheek Flap

The fundamental principle of this approach was to outfracture the maxilla, zygoma, and nasal bones, if required pedicled to the cheek flap, thus unlocking the gates to the difficult areas that include the posterior ethmoidal air cells, postnasal space, pterygopalatine fossa, infratemporal fossa, and upper part of the parapharyngeal space.

Extraoral incision followed the standard Weber-Fergusson approach with extension along the lateral crow's feet for better exposure. Soft tissues were reflected only to the extent required to make the osteotomy cuts and to apply the plates. Because this was an osteoplastic flap, excessive stripping was avoided as it would threaten the viability of the bony segment. 8 The extraoral incision continued intraorally along the buccal vestibule from the midline to the buttress on the involved side. A paramedian incision was given along the palate that continued horizontally along the junction of the hard and soft palate until the pterygomaxillary junction. Prefixing plates allowed accurate repositioning of the swung fragments and achieved good occlusion. Intraoral bone cuts divided the palate in the paramedian plane with the cut being extended through the maxillary alveolus between the central and lateral incisor. This cut was extended through the floor of the nose maintaining the intactness of the nasal lining. The facial bone cuts divided the zygomatic arch at its junction with the body of the malar bone, the lateral orbital rim inferiorly, the orbital floor just posterior or inferior to the rim staying lateral to the lacrimal apparatus, and the nasal process of the maxilla in an oblique line extending from the most medial extent of the orbital floor cut to the piriform rim below the inferior meatus

Integrity of the nasolacrimal duct was maintained. The osteotomy through the lateral nasal wall was performed horizontally below the inferior meatus and the pterygoid dysjunction performed with a curved chisel. The outfractured fragment was lifted up laterally and covered in saline-soaked gauze. The retromaxillary region was now freely accessible through a wide entry point. One vital point to be kept in mind was the utmost importance of a preoperative assessment of possible tumor adherence to the carotid, to avoid unintentional injury to the great vessels during tumor removal because this method precludes adequate carotid control.

Transmandibular (Lateral Approach)

A submandibular incision was taken from the mastoid process to the parasymphysis region. Dissection was done through the platysma and superficial layer of deep cervical fascia. The flap was reflected superiorly. Marginal mandibular nerve was identified and preserved. Facial vessels were divided and ligated. Retraction of the upper end of the divided facial vessels ensured further protection of marginal mandibular nerve. The lower border of the mandible was exposed. The pterygomasseteric sling was divided and the masseter muscle was elevated to expose the sigmoid notch and posterior border of the ramus. A subcondylar osteotomy was done. Plates were contoured and prefixed prior to completion of the osteotomy. Bone plates were removed and the osteotomy completed. A paramedian cut was done in the canine premolar region with a fine burr or saw. Plates were contoured, positioned, prefixed, and removed. The mobilized lateral segment of the mandible was lifted up. By this approach the parapharyngeal, retromaxillary, and infratemporal region could be exposed. One of the greatest advantages of this approach was that through the submandibular incision simultaneous control over the carotids was possible, and there was also adequate access to the neck extensions of the lesion. After satisfactory removal of the lesion, the segments were reduced and the plates refixed after checking the jaw relationship.

Zygomatico Temporal Osteotomy

A standard unicoronal scalp flap extending into the preauricular region was made. The incision was deepened to the galeal layer in the scalp and the temporoparietal fascia in the temple region. In the preauricular area, blunt dissection was done in the avascular subfascial plane anterior to the cartilage of the external auditory meatus to reach the root of the zygomatic arch where the periosteum was incised.

The subperiosteal flap was raised along this plane along the entire length of the zygomatic arch up to the level of the supraorbital rim. Pericranium was incised across the forehead and around the temporalis muscle to the level of the supramental crest and the posterior root of the zygomatic arch. The zygomatic bone was divided in three places after prefixing the miniplates. 9 The cuts were made as follows:

1 cm below the frontozygomatic suture with the burr or saw directed toward the inferior orbital fissure resulting in an oblique cut through the lateral orbital wall.

From the inferolateral corner of the orbital rim traveling the body of the zygoma to meet the first cut

Third cut was made obliquely bisecting the eminentia articulare of the zygomatic arch

The zygoma with the arch could now be outfractured and swung down pedicled to the masseter muscle. Coronoid was osteotomized and swung up pedicled to the temporalis to improve access. This finally exposed the area of infratemporal fossa and the undersurface of the greater wing of the sphenoid. A temporal craniotomy at this stage helped gain access to the middle cranial fossa and the intracranial extension of the lesion when deemed necessary.

Case 1: Myoepithelioma

A 40-year-old patient reported a recurrent myoepithelioma. He had undergone two previous surgeries for the same. The patient had symptoms of dysphagia, feeling of lump in the throat, nasal obstruction, and ear fullness. The mass was firm and nontender. CT demonstrated an extensive lesion involving the parapharyngeal space, obliterating the nasopharynx on the right side and extending up to the skull base ( Fig. 1 ). Because the lesion was well demarcated, it could be shelled out after a midfacial swing on the right side ( Figs. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). The performed plates were applied to refix the osteotomized fragments after the tumor excision. Myoepitheliomas are extremely rare tumors, accounting for 1% of salivary gland tumors. 10 11 Most of them are benign and involve the parotid where myoepithelial cells are predominantly seen. Radiation therapy was recommended in this case because it was a recurrent lesion.

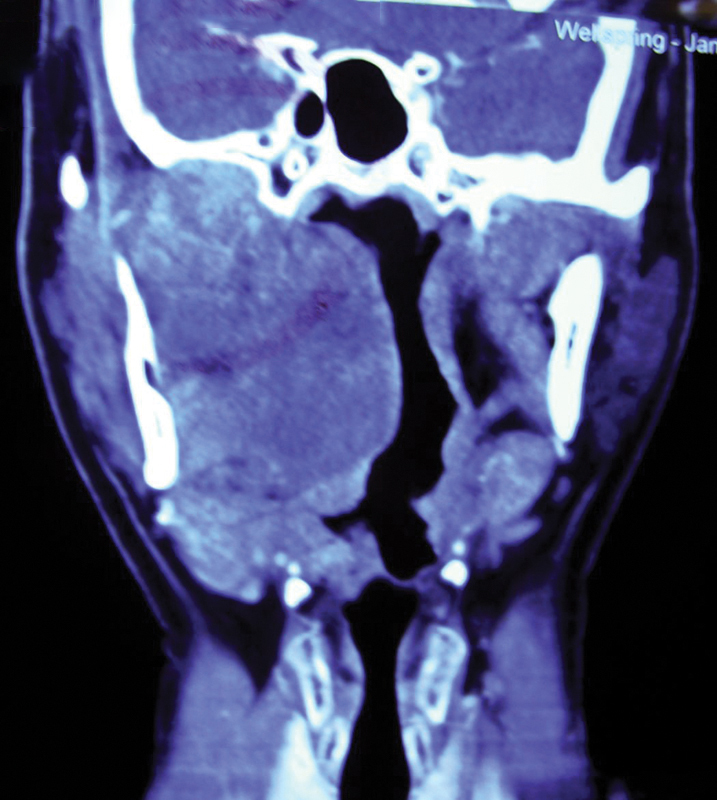

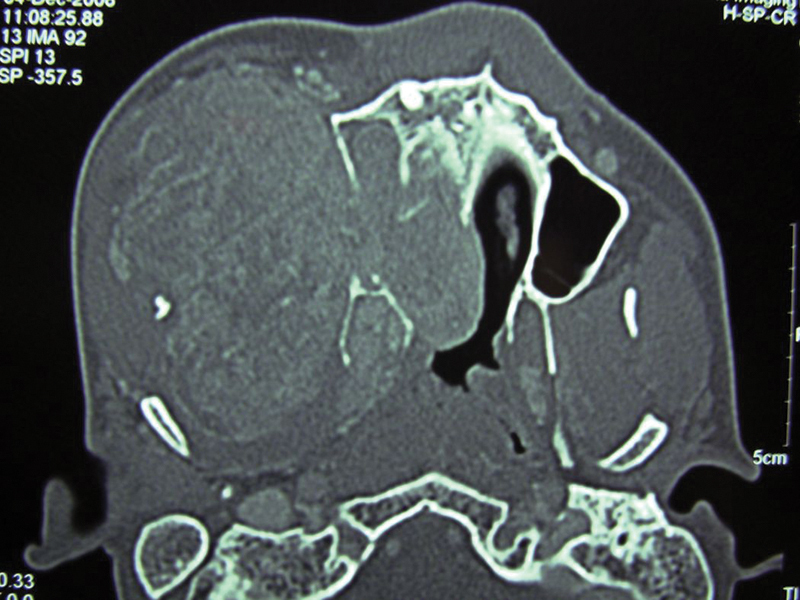

Fig. 1.

Case 1: Preoperative computed tomography coronal section showing right side parapharyngeal mass extending up to skull base.

Fig. 2.

Case 1: Weber-Ferguson incision performed on the right side.

Fig. 3.

Case 1: Osteotomy cut completed with minimal soft tissue reflection.

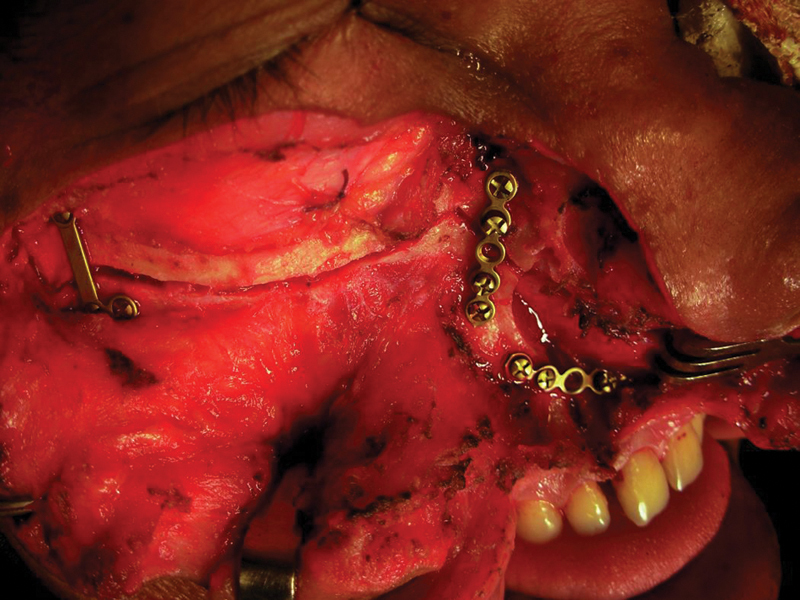

Fig. 4.

Case 1: Prefixed plates prior to complete separation of osteotomized fragment.

Fig. 5.

Case 1: Outfractured maxilla pedicled onto cheek flap and tumor exposed.

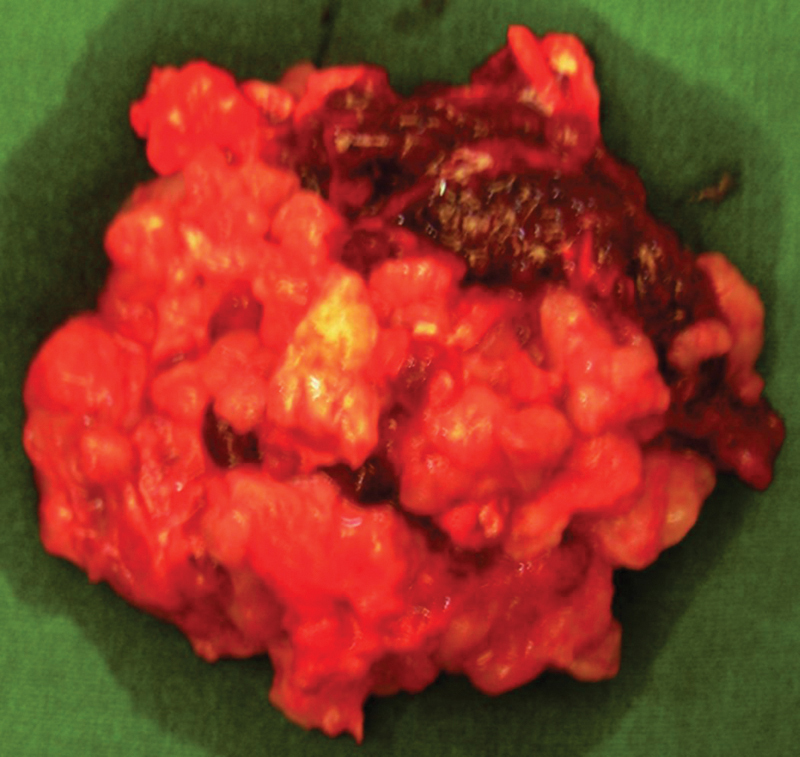

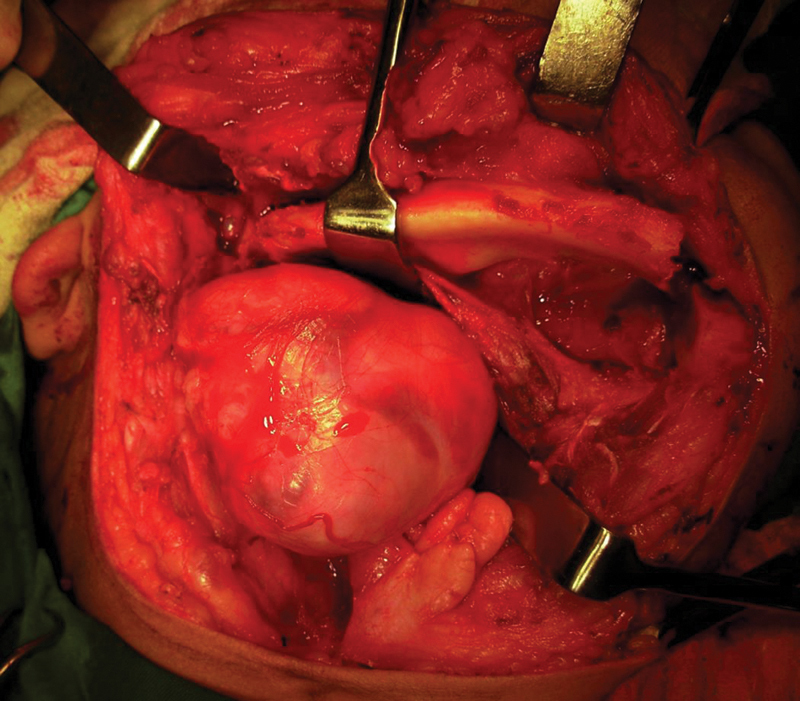

Fig. 6.

Case 1: Excised tumor mass.

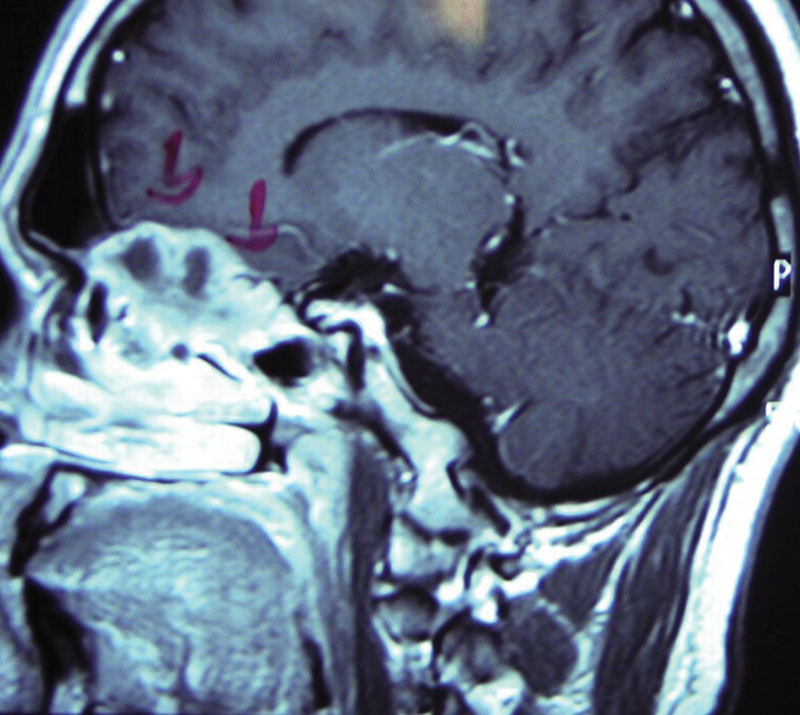

Case 2: Recurrent Meningioma

This patient was referred by a neurosurgeon after he had been operated on twice for a meningioma. CT demonstrated a recurrence of the tumor in the left temporal region with extension into the infratemporal fossa ( Figs. 7 , 8 ). It was a recurrent tumor, so good exposure was mandatory for a sufficient clearance. The zygomaticotemporal approach ( Fig. 9 ) gave direct access to the retrozygomatic and infratemporal region. The intracranial component was removed by a temporal craniotomy and dural repair was performed. At 3-year follow-up, the patient showed no sign of recurrence.

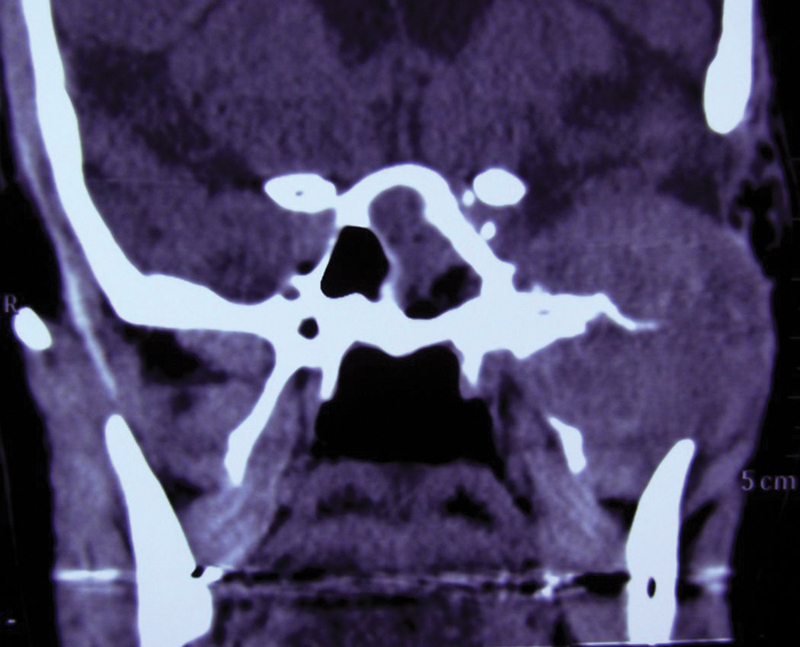

Fig. 7.

Case 2: Preoperative computed tomography showing mass in left infratemporal fossa eroding pterygoid plates, base of middle cranial fossa, and intracranial involvement.

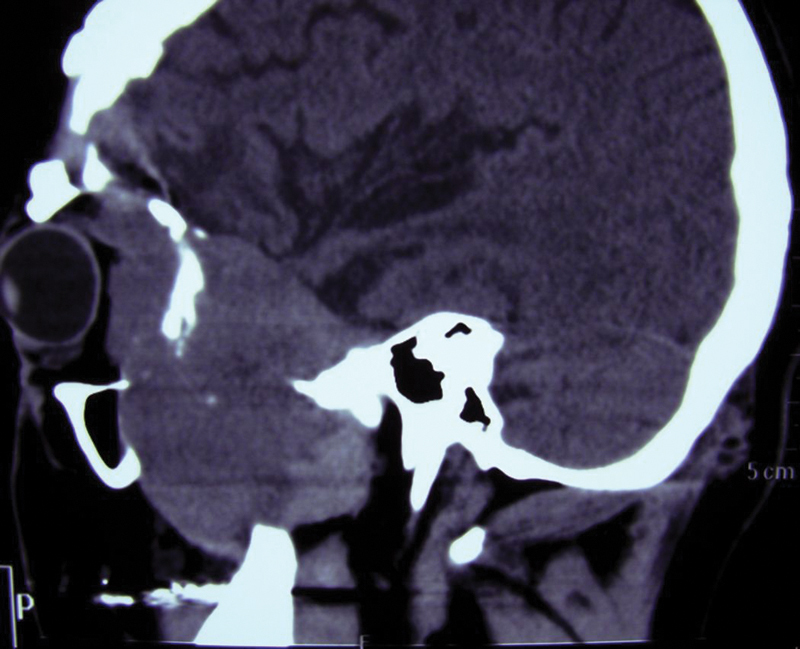

Fig. 8.

Case 2: Preoperative sagittal computed tomography showing retromaxillary, retro-orbital, and intracranial extent of the tumor.

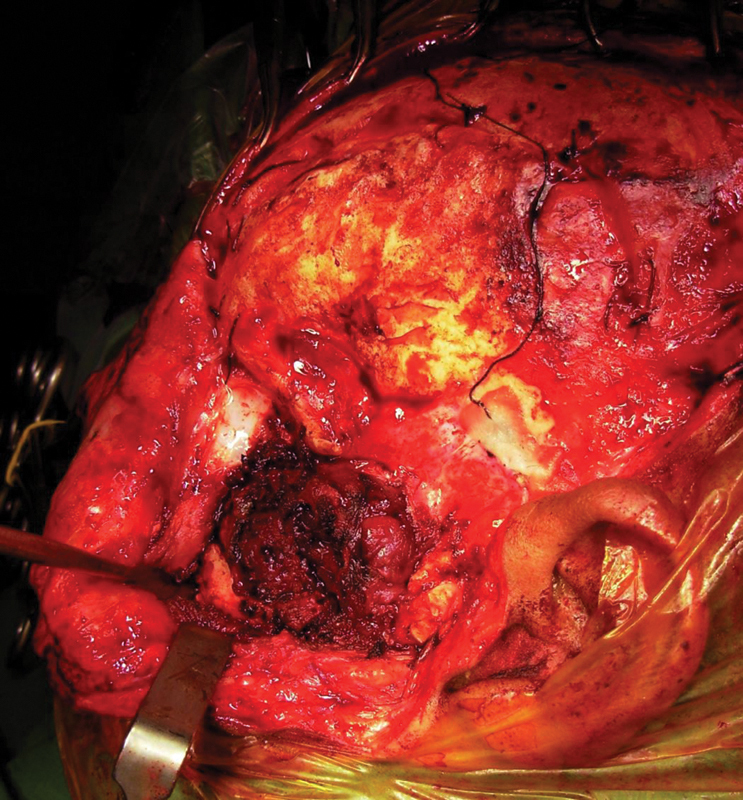

Fig. 9.

Case 2: Zygomatic arch osteotomized and turned down; mass in infratemporal fossa exposed and removed piecemeal with cautery.

Case 3: Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA), one of the most common tumors of the nasopharynx, is a histologically benign yet locally aggressive tumor. 12 It is believed to originate in the posterolateral wall of the nasal cavity in the sphenopalatine area from where it can spread extensively. 13

This 23-year-old patient presented with a history of epistaxis. He had been investigated for >2 years at various centers. Digital subtraction angiography had demonstrated the classical vascular blush of a nasopharyngeal angiofibroma of the postnasal space on the right side. Embolization had been attempted twice without any significant reduction in size. The patient presented to us with a nasopharyngeal nodular mass pink to purple in color, palatal bulge ( Fig. 10 ), and swelling extending to the cheek and over the zygoma. There was no proptosis. The lateral facial swelling was an ominous indication of extensive tumor spread.

Fig. 10.

Case 3: Intraoral preoperative image showing the palatal bulge and a reddish pink soft compressible mass in the tuberosity region.

CT demonstrated that the soft tissue mass had eroded the pterygoid plates, was obliterating the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity on the right side, eroded a part of the nasal septum, was filling the infratemporal fossa, pterygopalatine fossa, and extending into the cheek ( Figs. 11 , 12 ). CT angiography demonstrated a massive vascular tumor involving the postnasal, retromaxillary, and infratemporal space on the right side with multiple feeder vessels from the ipsilateral facial, internal maxillary, ascending pharyngeal, and internal carotid artery ( Fig. 13 ). The unsuccessful attempts at embolization had led to the tumor parasitizing bilateral blood supply from every nearby vessel including the vertebral and thyrocervical vessels. The primary treatment modalities for JNA that have been tried are surgery or radiation. Both of these have had their own merits and drawbacks. Although most studies have discussed the use of either of these approaches, we contemplated preirradiating the tumor with megavoltage therapy, expecting to reduce it to more surgically manageable proportions. 12 13 The tumor mass was subjected to a radiation dose of 2500 cGy. Following radiation there was a dramatic shrinkage of the tumor. A re-embolization of internal maxillary vessels was attempted prior to surgery that failed, and the tumor mass was safely excised through a midfacial swing. The external carotid was clamped on the involved side during the procedure. Intraoperative blood loss was ∼ 1200 cc, and he needed transfusion of 3 units of whole blood. The patient has been followed up for almost 2 years, and follow-up scans demonstrated good healing with no evidence of recurrence ( Fig. 14 ).

Fig. 11.

Case 3: Preirradiation axial section computed tomography demonstrating a huge parapharyngeal mass eroding the pterygoid plates and nasal septum and obliterating the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus on the same side extending onto the cheek.

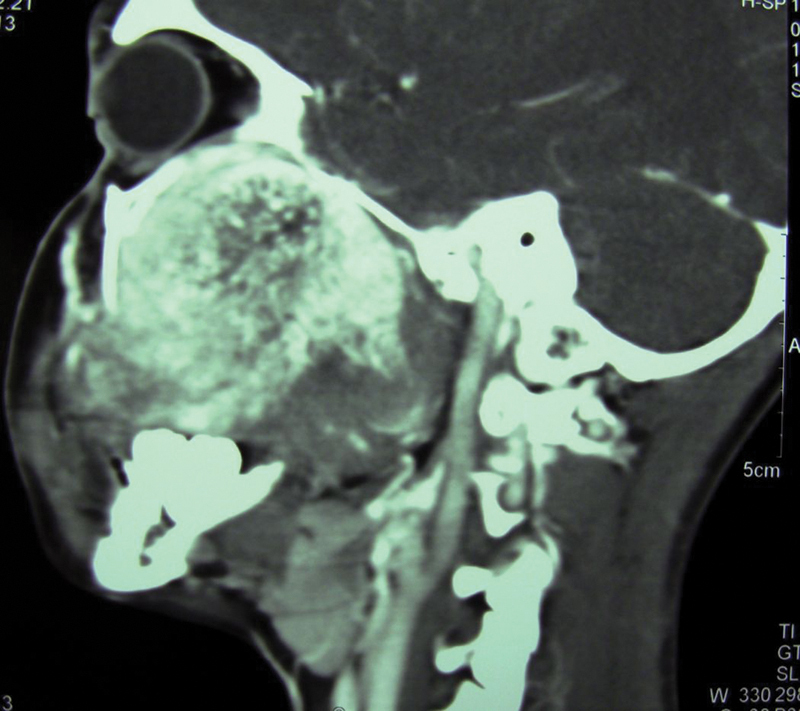

Fig. 12.

Case 3: Preirradiation computed tomography sagittal section showing extension of lesion up to the cranial base with destruction of the walls of the maxillary sinus.

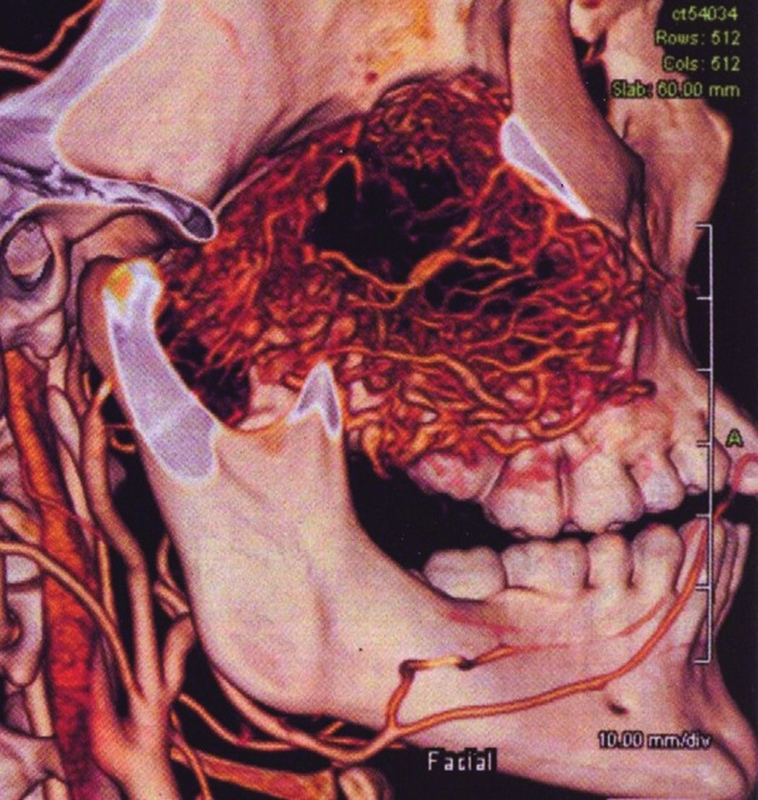

Fig. 13.

Case 3: Preoperative computed tomography angiography demonstrating the tumor with feeders from the ipsilateral internal maxillary, and the ascending pharyngeal and internal carotid arteries.

Fig. 14.

Case 3: Postoperative computed tomography after 1 year showing good healing and no evidence of recurrence.

Case 4: Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

This patient was an adolescent boy who presented with unilateral nasal obstruction on the left side with a history of epistaxis. Clinical examination revealed a purplish beefy red smooth lobulated mass in the left nasopharynx and nasal cavity. The mass was compressible. CT revealed a mass in the left pterygomaxillary space extending into the nasal cavity. The Holman Miller sign was positive on CT, which is the characteristic anterior bowing of the posterior maxillary wall due to pterygomaxillary space lesions 14 ( Fig. 15 ). Preoperative angiography revealed a vascular blush with the internal maxillary the main feeding vessel. Preoperative selective embolization of feeding vessels was done 72 hours prior to surgery because it is believed to reduce intraoperative blood loss considerably, and the mass was surgically excised after performing a maxillotomy pedicled to cheek flap access osteotomy. 15 Complete resection was possible with the least morbidity through this approach.

Fig. 15.

Case 4: Preoperative axial computed tomography showing retromaxillary tumor mass with anterior bowing of the posterior maxillary wall and obliteration of the right nasal cavity.

Case 5: Hemangioendothelioma

Hemangioendothelioma, a rare vascular tumor with a potential for malignancy, is considered intermediate between a benign hemangioma and malignant hemangioma. A 17-year-old patient presented with a moderate-size tumor on the left side of the hard palate that was increasing in size over the last 2 months. He had a history of profuse nasal bleeding. The intraoral mass was spontaneously bleeding in some places ( Fig. 16 ). CT demonstrated infiltration of the mass into the left nasal cavity, postnasal, and retromaxillary space. Microscopic appearance was varied and showed immature endothelial cells arranged in the shape of threads and at places protruding into the capillary lumen. Stroma was scarce. The tumor was excised after a midfacial osteotomy. Healing was uneventful, and the patient had no functional or aesthetic morbidity.

Fig. 16.

Case 5: Preoperative intraoral picture of swelling in the left side of the palate with areas of spontaneous bleeding.

Case 6: Recurrent Primordial Cyst

A 35-year-old patient reported with a history of pain and recurrent swelling in the left temporal region with difficulty opening the mouth. She had undergone eight surgeries in the past for a recurrent primordial cyst that had first occurred in the left body and ramus region of the mandible. The patient showed signs of facial nerve paralysis due to previous surgery. MRI revealed a cystic lesion in the left infratemporal space measuring ∼ 2.5 × 3 cm and extending up to the base of the skull ( Fig. 17 , 18 ). This case further reinforced the fact that some of the odontogenic keratocysts, particularly with a parakeratinized lining, can be regarded as a benign neoplasm like an ameloblastoma with aggressive unremitting growth. 16 To avoid any further recurrence and damage, a midfacial swing osteotomy was done that ensured good access and complete clearance of the lesion with adequate margin. Two-year follow-up showed no sign of recurrence.

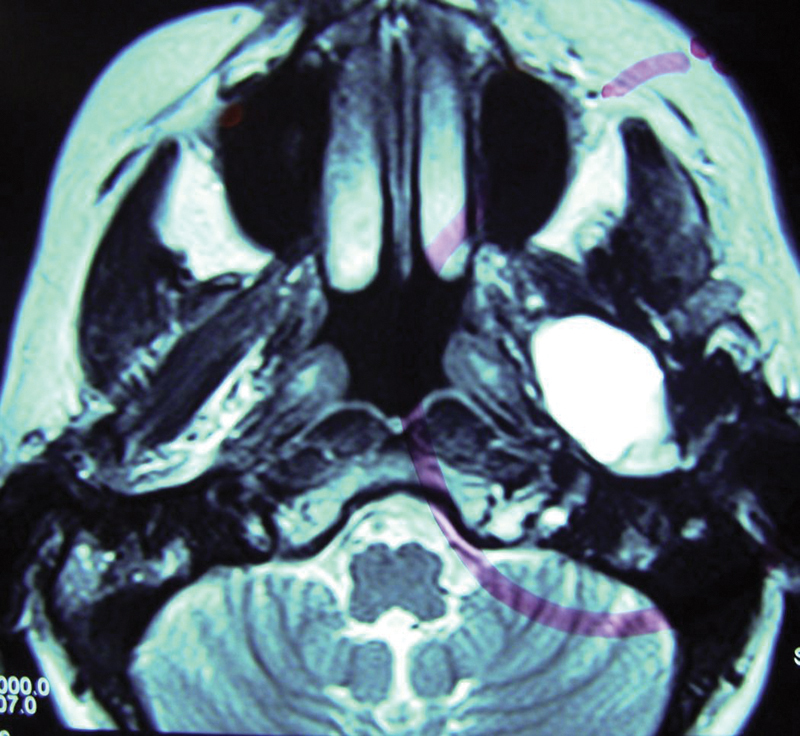

Fig. 17.

Case 6: Magnetic resonance imaging axial section showing a well-defined enhancing lesion in the retromaxillary region.

Fig. 18.

Case 6: Magnetic resonance imaging coronal section showing a well-defined enhancing lesion abutting the skull base.

Case 7: Aspergilloma

Aspergilloma or aspergillus mycetoma is a noninvasive extramucosal mycotic infection of aerogenic, odontogenic, or mixed origin. 17 A 35-year-old male patient reported to us with the complaint of proptosis of the right eye with diplopia of 8 months' duration. He had no pain, swelling, or nasal discharge. MRI revealed a soft tissue mass involving the roof of the nasal cavity and ethmoidal sinuses on the right side. There was destruction of the medial orbital wall and floor and involvement of the extraoral muscles on the medial and inferior aspect on the right side. The mass was herniating into the maxillary sinus ( Fig. 19 ). The lesion had eroded the cribriform plate and was extending intracranially. 18 MRI also revealed heterogenous opacities with metal dense spots in the intracranial part of the lesion ( Fig. 20 ). Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was inconclusive. To arrive at a more definitive diagnosis, a complete excision of the lesion was done through a midfacial swing approach. Dura was left intact, and the lesion was excised. Frozen section diagnosed aspergillosis. Microscopic examination of the excised mass revealed that it was a fungus ball with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and fungal hyphae with acute angulations. It was concluded to be a case of aspergilloma. Adjuvant antifungal therapy with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily was administered for the first 6 months. The dose was then tapered to 100 mg twice daily for the next 3 months. The radiodense regions were probably calcium phosphate or calcium sulfate deposition in areas of necrotic mycelium. A repeat CT taken 1 year after surgery revealed no signs of the disease.

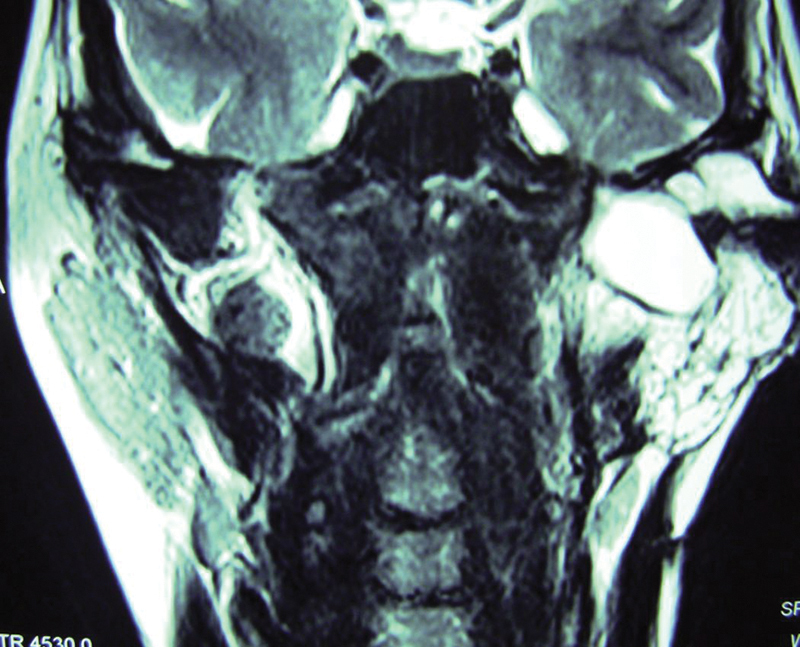

Fig. 19.

Case 7: Magnetic resonance imaging coronal section showing the lesion involving right nasal cavity, ethmoidal sinus, medial aspect, and floor of orbit, herniating into the right maxillary sinus.

Fig. 20.

Case 7: Magnetic resonance imaging sagittal section showing intracranial component of lesion with metal dense spots.

Case 8: Pleomorphic Adenoma of Deep Lobe Parotid

The so-called deep lobe of the parotid is said to consist arbitrarily of two portions: one part that lies deep to the facial nerve but still lateral to the ramus, and the second, medial mandibular component, that may extend medial to the ramus toward the parapharyngeal space. Tumors of the deep lobe that involve this parapharyngeal extension are extremely rare and account for < 1%. Diagnosis is late because they are relatively asymptomatic and may not present as a preauricular swelling. Incisional biopsies of deep lobe tumors are contraindicated because they are fraught with the risk of tumor seeding, breach of capsule increasing chances of recurrence, adherence of capsule to overlying epithelium leading to tearing during excision, and infection. Deep lobe tumors characteristically have a thicker capsule; rarely do tumor cells penetrate the capsule or destroy it.

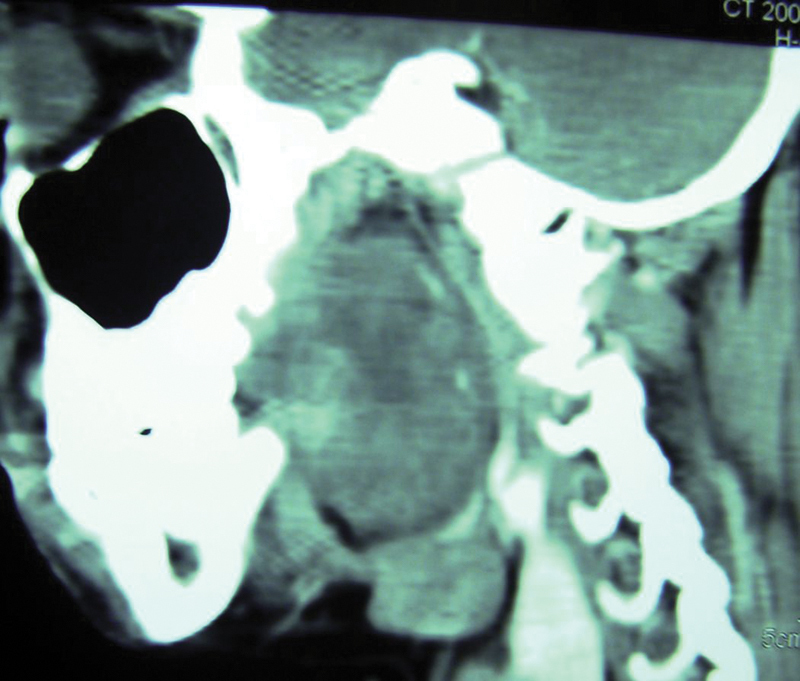

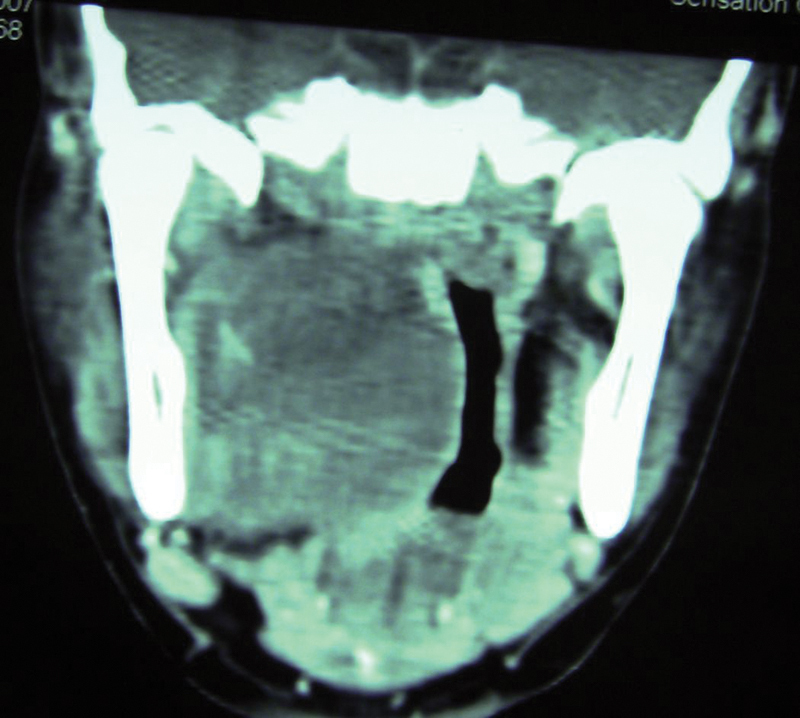

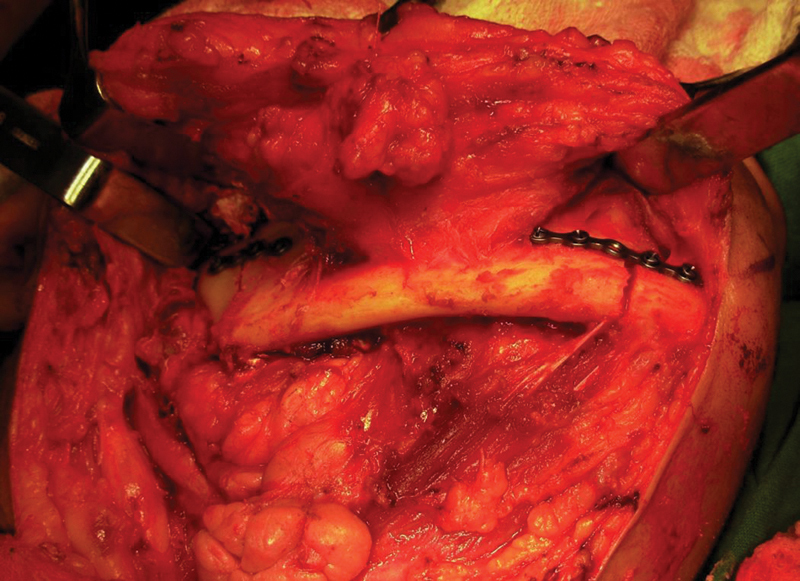

A 35-year-old female patient reported with difficulty in swallowing and breathing while lying in the supine position. Intraoral examination showed a bulging lesion in the right parapharyngeal space that was abutting the soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall. She had no eustachian tube dysfunction or signs of extension up to the skull base ( Fig. 21 , 22 ). The lateral approach through the mandible provided excellent access to the tumor through the stylomandibular tunnel without any breach in the oral mucosa ( Fig. 23 ). The tumor was well encapsulated and was shelled out by blunt finger dissection ( Fig. 24 ). Because the tumor involved only the parapharyngeal component, it was well away from the facial nerve. Postoperative healing was uneventful with no functional deficit.

Fig. 21.

Case 8: Computed tomography scan sagittal section showing a 4 × 3 cm mass almost completely obliterating the pharyngeal space.

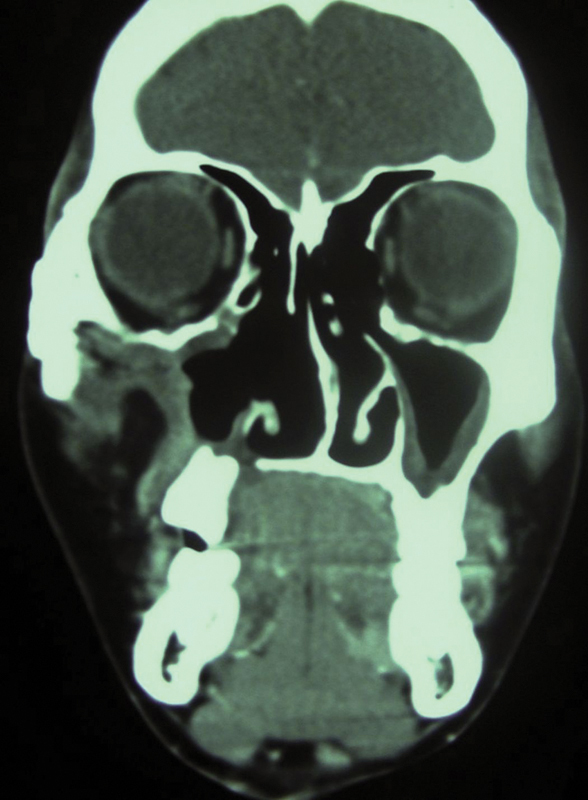

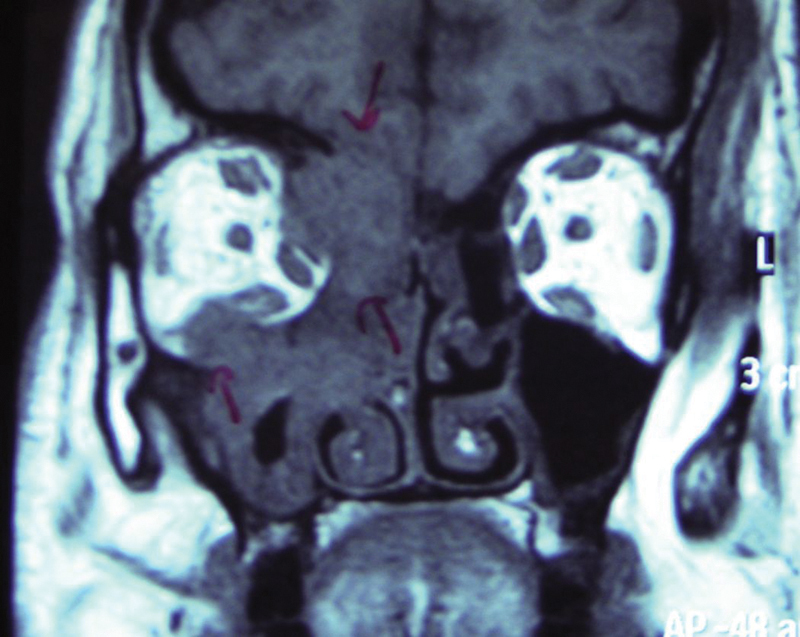

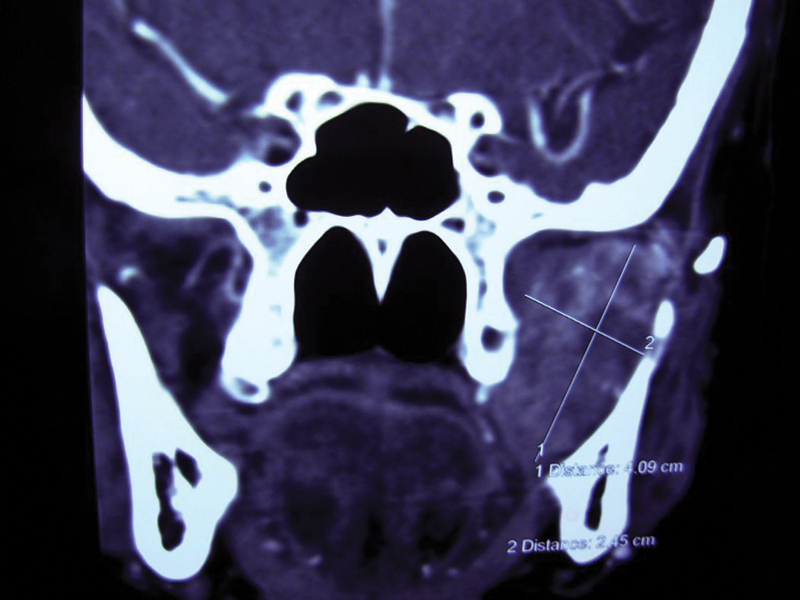

Fig. 22.

Case 8: Preoperative computed tomography scan coronal section showing the mass in the lateral pharyngeal space right side.

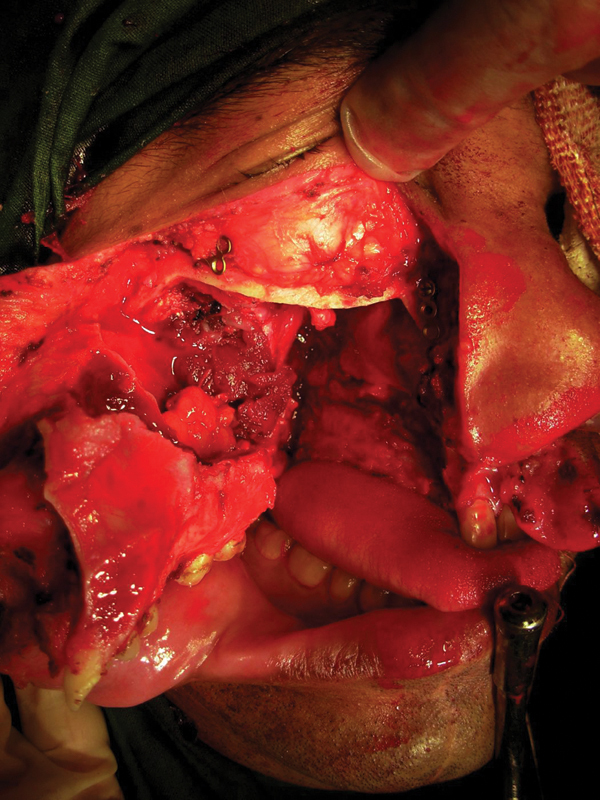

Fig. 23.

Case 8: Paramedian and subcondylar osteotomy of mandible done for lateral approach with prefixed plates.

Fig. 24.

Case 8: Well-encapsulated tumor mass removed by blunt finger dissection after lateral retraction of osteotomized fragment.

Case 9: Pleomorphic Adenoma of Deep Lobe of Parotid

A 65-year-old woman reported with the feeling of lump in the throat, difficulty in swallowing, and increasing discomfort. CT images ( Fig. 25 ) showed a dense homogeneous mass ∼ 2 cm × 1 cm in diameter originating in the deep lobe of the parotid and extensively involving the parapharyngeal space. Fine-needle aspiration cytology suggested a pleomorphic adenoma that was removed by a lateral mandibular approach. The postoperative course was uneventful with no functional deficit.

Fig. 25.

Case 9: Coronal computed tomography showing a well-defined 2 × 1 cm lesion in the left parapharyngeal area extending up to the infratemporal space.

Discussion

Skull base lesions pose a great challenge even to the best of surgeons. It is the fear of endangering vital structures like the great vessels and cranial nerves that lead to incomplete resection of pathologies around this area and a poor prognosis. This is quite obvious from the fact that three of the nine cases (33.3%) presented here were recurrent lesions.

Skull base lesions warrant meticulous clinical examination including cranial nerve status and vascular assessment. CT and MRI help to evaluate tumor dimensions, its relation to the pterygoid plates and skull base, and proximity to the internal carotid artery. CT angiography helps trace the feeding vessels and the need for their embolization. MR angiography allows a noninvasive acquisition of vascular anatomy and gives the exact location of the internal carotid artery and its relative position with respect to the lesion at various levels. Selective carotid angiograms help assess the intracranial crossover blood supply. This helps us to have an idea of the possibility of a cerebrovascular accident in the event of an internal carotid ligation intraoperatively.

The skull base, particularly the area to the body and the greater wing of the sphenoid, has been found to house a wide spectrum of pathologies. Along with the growing list of tumors, a multitude of approaches to reach this area have also been reported. Transfacial swing approaches maximize access with minimal morbidity and add a great degree of flexibility. The uniqueness of these approaches lies in the fact that they allow precise tumor resection through the least target distance. Access can be extended superiorly and inferiorly by mobilization of adjacent modules and the internal carotid artery exposed from the bifurcation to the petrous canal if required. They offer a great solution to varied pathologies with intra- and extracranial involvement in the central and anterolateral compartment of the skull base.

An ideal access osteotomy has the following features:

Provides increased and direct access

Can be extended intraoperatively

Minimizes brain retraction when intracranial contents are exposed

Offers minimal cosmetic and functional morbidity

Only increases operative time minimally

Exposes the lesion from as many angles as possible

The selection of approach is tailored to suit the needs of each individual patient. 19 Sometimes there might be a need to mobilize multiple modules of the facial skeleton to achieve the best results. In the series presented here, these are some of the criteria that helped us in the right selection of the approach:

Type of pathology (benign/ malignant)

Dimensions of the lesion

Location of target area

Presence of intracranial extension

Proximity to major vessels

Possibility of complete resectability with safe clearance

Degree and quality of exposure required

Need to access the great vessels proximally and distally

Contraindications to aggressive resection were poorly controlled systemic disease, extensive intracranial involvement, and radiosensitive tumors.

Transfacial swing osteotomies have opened the gate to a wide spectrum of skull base tumors with extensive involvement. The midfacial swing exposes tumors that involve extracranial and intracranial midline and paramidline compartments like hemangioendotheliomas and juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. It exposes the clivus right from the sella turcica to the foramen magnum and provides excellent access to retromaxillary and postnasal areas. This is a very effective, safe option for recurrent lesions in the retromaxillary area as evidenced in two of the cases.

The subcranial zygomaticotemporal osteotomies provide wide exposure of lateral orbital contents, retromaxillary, pterygoid, and infratemporal fossa. Some difficulties with this approach are that the access gets more limited as we get deeper, and exposure of the lateral pharyngeal wall may need sectioning of the mandibular nerve and resection of the pterygoid plates.

Mandible becomes the skeletal module of choice when wide exposure of tumors of the parapharyngeal area, central skull base, and lower part of infratemporal fossa is required. There are two surgical options for handling lesions involving the areas just described. First is a simple mandibular anterior distraction as proposed by Martin in 1957. It sometimes entails resecting the styloid process, stylomandibular ligament, and posterior margin of the ramus. 20 This approach gives only limited access to the superior portion of large neoplastic growths with increasing risk of injury to major vascular structures. The second option is to osteotomize the mandible (mandibulotomy approach). The central or midline mandibulotomy approach through the mandible is advantageous when lesions are in the oropharynx, tonsillar region, base of the tongue, posterior floor of the mouth, and anterior pterygomandibular space. Access to parapharyngeal pathologies is restricted with the central approach due to the depth of the target area necessitating greater retraction of the mandible leading to traction on the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves and increasing risk of damage to the temporomandibular joint, thus making the lateral approach more preferable. The lateral approach through the mandible that was used in the two cases described was found to provide a direct short-distance route for removal of deep lobe tumors, and lower parapharyngeal and retromaxillary tumors. This was first described by Seward in 1985. The oral cavity is not entered, and it avoids risk of an orocutaneous fistula. It preserves the inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve, avoids a lip, and also provides good access to the neck for vascular control when required.

All these osteotomies incorporate techniques learned in trauma and orthognathic surgery to facilitate safe and radical oncologic surgery in a difficult region with minimal morbidity and excellent cosmetic results. There have been concerns of morbidity related to these approaches resulting from the exposure of the nasopharyngeal area and paranasal sinuses. This is specifically related to the increased risk of meningitis and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks. However, it is imperative to comprehend that patients outcome is more significantly related to complete resection of the lesion and should not be compromised by inadequate exposure.

Although technological advances have expanded the use of endoscopic techniques to include endonasal approaches to skull base lesions, its scope has been limited. It is a safe and effective option for patients with small midline tumors (< 4 cm in diameter or 40 cc in volume). 21 Lateral skull base lesions extending beyond the pterygoid plates and carotids and lesions involving the soft tissues of the orbit lie outside the endoscopic corridor. Further literature review reveals that prospective investigations with longer follow-up are needed to address more definitively the efficacy of endoscopic skull base surgery.

The size of the lesion, involvement of lateral skull base, and parapharyngeal space (cases 8 and 9), recurrent nature (case 1, 2, and 6), extensive vascularity (cases 3, 4, and 5), and involvement of soft tissue of the orbit (case 7) made us choose transfacial swing approaches that ensured complete and safe resection of relatively large lesions with no sacrifice of normal bone. There were minimal complications in terms of CSF leaks, functional and aesthetic morbidity, and postoperative infection.

Conclusion

Transfacial swing open approaches to skull base lesions still have a positive and effective role to play in the management of skull base lesions even in this era of minimal access surgery.

References

- 1.Richardson M S.Pathology of skull base tumors Otolaryngol Clin North Am 200134061025–1042., vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreira-Gonzalez A, Pieper D R, Cambra J B, Simman R, Jackson I T; Andrea Moreira Ganzalez.Skull base tumors: a comprehensive review of transfacial swing osteotomy approaches Plast Reconstr Surg 200511503711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drommer R B. The history of the “Le Fort I osteotomy.”. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14(03):119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanley R B.Transfacial access osteotomies to the central and anterolateral skull base In: Greenberg A M, Prein J.Craniomaxillofacial Reconstructive and Corrective Bone Surgery Principles of Internal Fixation Using AO/ASIF TechniqueNew York, NY: Springer; 2002489–496. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbabaa S K, Al-Mefty O. Craniofacial approach for anterior skull-base lesions. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2010;18(02):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ammirati M, Bernardo A.Analytical evaluation of complex anterior approaches to the cranial base: an anatomic study Neurosurgery 199843061398–1407.; discussion 1407–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ammirati M, Ma J, Clicatham M L, Mei Z T, Bloch J, Becker D P. The mandibular swing transcervical approach to skull base: anatomical study. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(04):673–681. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.4.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown A MS, Lavery K M, Millar B G. The transfacial approach to the postnasal space and retromaxillary structures. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29(04):230–236. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90189-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grime P D, Haskell R, Robertson I, Gullan R. Transfacial access for neurosurgical procedures: an extended role for the maxillofacial surgeon. II. Middle cranial fossa, infratemporal fossa and pterygoid space. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;20(05):291–295. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnest L, Appel B N, Perez H, El-Attar A M. Myoepitheliomas of the head & neck: case report and review. J Surg Oncol. 1985;28(01):21–28. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930280107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sciubba J J, Brannon R B. Myoepithelioma of salivary glands: report of 23 cases. Cancer. 1982;49(03):562–572. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820201)49:3<562::aid-cncr2820490328>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields J N, Halverson K J, Devineni V R, Simpson J R, Perez C A. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: efficacy of radiation therapy. Radiology. 1990;176(01):263–265. doi: 10.1148/radiology.176.1.2162070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDaniel R K, Houston G D. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with lateral extension into the cheek: report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53(04):473–476. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forer B, Derowe A, Cohen J T, Landsberg R, Gil Z, Fliss D M. Surgical approaches to juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;12(04):214–218. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman B, Bublik M, Younis R. Endoscopic embolization and resection of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Oper Tech Otolaryngol. 2009;20:183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell R B, Dierks E J. Treatment options for the recurrent odontogenic keratocyst. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2003;15(03):429–446. doi: 10.1016/S1042-3699(03)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa F, Polini F, Zerman N, Robiony M, Toro C, Politi M. Surgical treatment of Aspergillus mycetomas of the maxillary sinus: review of the literature . Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(06):e23–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Notani K, Satoh C, Hashimoto I, Makino S, Kitada H, Fukuda H. Intracranial Aspergillus infection from the paranasal sinus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(01):9–11. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grime P D, Haskell R, Robertson I, Gullan R. Transfacial access for neurosurgical procedures: an extended role for the maxillofacial surgeon. I. The upper cervical spine and clivus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;20(05):285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozzetti A, Biglioli F, Gianni A B, Brusati R. Mandibulotomy for access to benign deep lobe parotid tumors with parapharyngeal extension: report of four cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56(02):272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raper D MS, Komotar R J, Starke R M, Anand V K, Shwartz T H. Endoscopic versus open approaches to skull base: a comprehensive literature review. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;22(04):302–307. [Google Scholar]