Abstract

Background Cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is rare and presents with increased intracranial pressure and cerebellar signs. The recommended treatment is radical resection, if possible, with radiation and chemotherapy.

Clinical Presentation A 53-year-old man presented with hypertensive cerebellar bleeding and a 2-day history of severe headaches, nausea, vomiting, gait instability, and elevated blood pressure. Computed tomography (CT) showed a left cerebellar hematoma with no obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid and no hydrocephalus. CT angiography showed no signs of pathologic blood vessels in the posterior cranial fossa. The patient was observed in the hospital and discharged. Subsequent CT showed complete hematoma resorption. Two weeks later, he developed headaches, nausea, and worsening cerebellar symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 4-cm diameter tumor in the left cerebellar hemisphere where the hemorrhage was located. The tumor was radically resected and diagnosed as GBM. The patient underwent radiation and chemotherapy. At a follow-up of 1.5 years, MRIs showed no tumor recurrence.

Conclusion Hypertensive cerebellar hemorrhage may be the first presentation of underlying tumor, specifically GBM. Patients undergoing surgery for cerebellar hemorrhage should have clot specimens sent for histologic examination and have pre- and postcontrast MRIs. Patients not undergoing surgery should have MRIs done after hematoma resolution to rule out underlying tumor.

Keywords: bleeding, cerebellar hemorrhage, cerebellum, glioblastoma multiforme, hypertension, hypertensive cerebellar bleed

Background and Importance

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and malignant astrocytic brain tumor,1 2 3 4 5 6 representing 15 to 20% of all intracranial tumors. They account for about half of all cerebral gliomas.3 4 7 8 They most often arise in the cerebral hemispheres with a predilection for the frontal and temporal lobes.2 7 9 10 The cerebellum is the most infrequent location of GBMs,1 3 4 11 12 13 comprising only a small proportion of all GBM cases found in the brain (0.24–3.4%). Only ∼ 180 cases have been reported.5 8 10 14 15 16 17 18

An initial presentation of a cerebellar GBM as a hypertensive cerebellar hemorrhage has not been reported thus far. We present the unique case of a patient who initially presented with a massive hypertensive hemorrhage in the left cerebellar hemisphere. A month after the hematoma resolved, a cerebellar GBM was identified. Details of the clinical picture, radiologic presentation, and surgical and oncologic treatment of this case are described.

Clinical Presentation

A middle-age man with a history of hypertension was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) from the emergency department. The patient had a clinical history of generalized headache, gait and trunk instability, and elevated blood pressure. The symptoms had been worsening for 2 days before admission. At the time of presentation, he had been mildly lethargic with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14. His neurologic signs included cerebellar ataxia, tandem gait inability, and dysmetria. The patient had a markedly elevated blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg, but the results of all routine biochemical investigations were normal. A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast revealed a large hemorrhage in the left cerebellar hemisphere, measuring ∼ 4 cm in diameter, but no obstruction of the fourth ventricle or hydrocephalus (Fig. 1). CT angiography did not reveal any abnormalities in the blood vessels of the cerebellum (Fig. 2). The patient remained clinically stable during observation and was treated conservatively. He spent 5 days in the ICU and another 5 days on the neurosurgery hospital service. There were no indications for surgery. During his hospital stay, CT scans were repeated twice and revealed a gradual resorption of blood in the left cerebellar hemisphere.

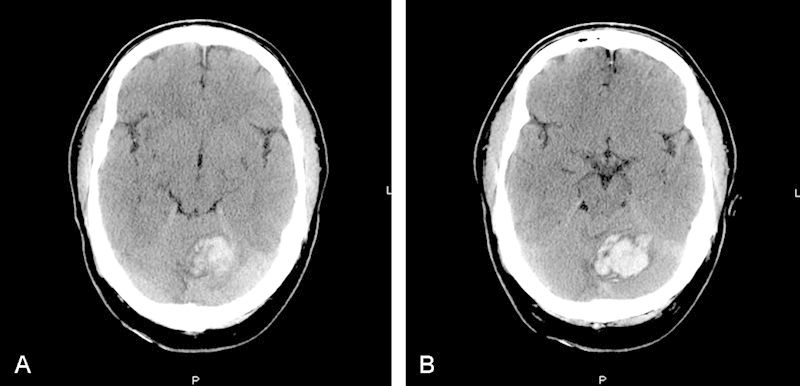

Fig. 1.

(A,B) The axial T1-weighted noncontrast computed tomography images at presentation. Note the large hyperdense area in the left cerebellar hemisphere consistent with hypertensive cerebellar hemorrhage.

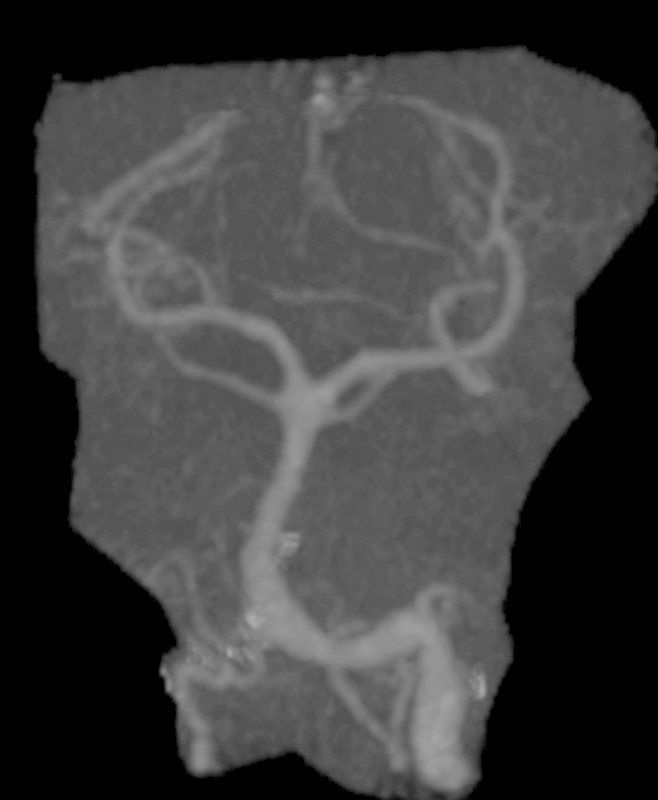

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography angiography of the posterior cranial circulation. No abnormal blood vessels were seen.

The patient was discharged with improvement of neurologic deficits, and a follow-up CT scan of the brain showed complete resorption of the hemorrhage 2 weeks after discharge (Fig. 3). At his follow-up appointment 2 weeks later, however, the results of the patient's neurologic examination were worse. He had developed progressively worsening cerebellar signs with gait disturbance, nystagmus, nausea, and clumsiness of the extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the brain revealed a left cerebellar mass (Fig. 4).

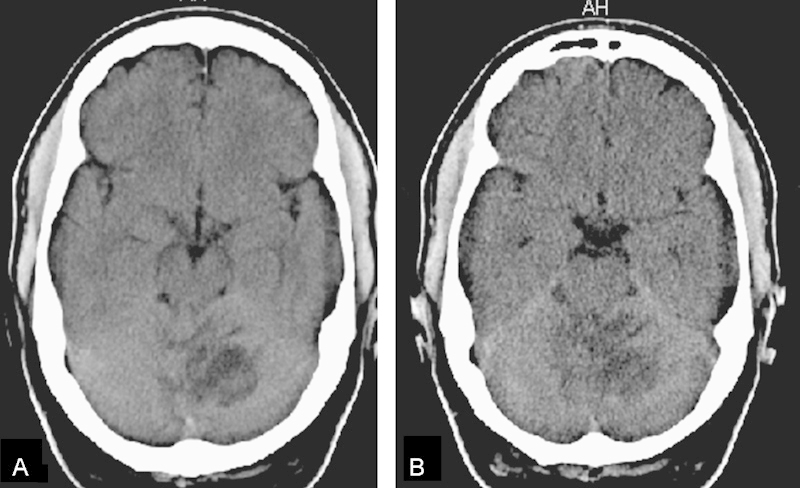

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Axial noncontrast computed tomography scan 2 weeks after hemorrhage. Note the hypodense area in the left cerebellar hemisphere showing the hematoma resorption.

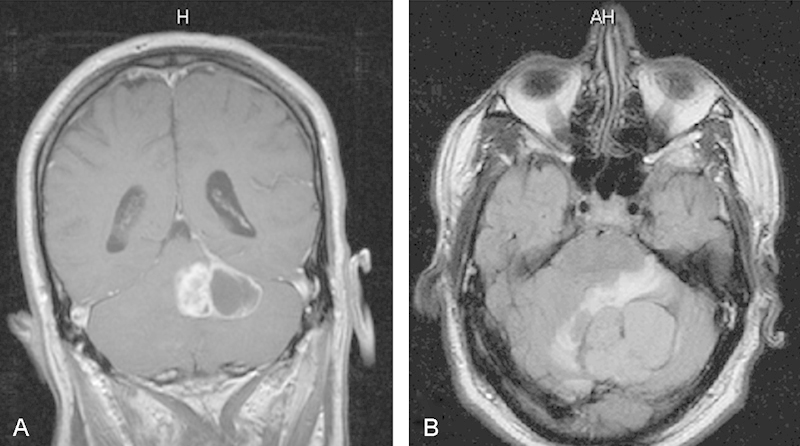

Fig. 4.

(A) Coronal T1-weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and (B) axial flair MRI. Note the left cerebellar mass lesion with cystic areas. There is nonhomogeneous tumor enhancement (A) and some perilesional edema (B).

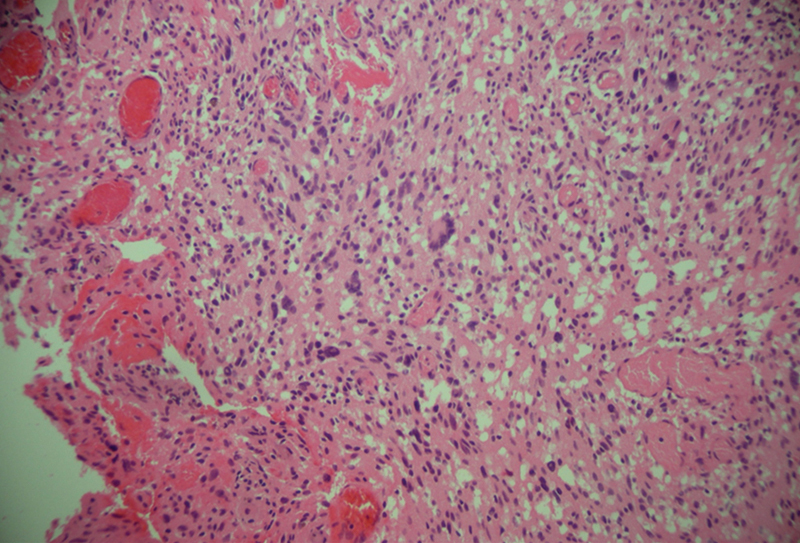

Subsequently, the patient underwent a posterior fossa craniotomy by the senior author (K.A.) with radical microsurgical resection of the tumor. Microscopic examination of the tissues revealed normal cerebellar tissue and the presence of a neoplasm. The tumor displayed a pattern of cellular organization not normally seen in the cerebellum or cerebrum. Dominant histopathologic features included hypercellularity, nuclear anisonucleosis and hyperchromatism, disorganization, hypervascularity, endothelial proliferation, extensive microcystic changes, and “malignant” giant cells. The tumor cells stained uniformly positive for gliofibrillary acid protein and neuron specific enolase, and they did not have the reticulin stain pattern of a cerebellar hemangioblastoma (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The hypercellular cerebellar specimen reveals disorganized architecture with multiple giant hyperchromatic nuclei including several malignant multinucleate giant cells, extensive microcystic change, and vascular endothelial proliferation consistent with glioblastoma multiforme (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×400).

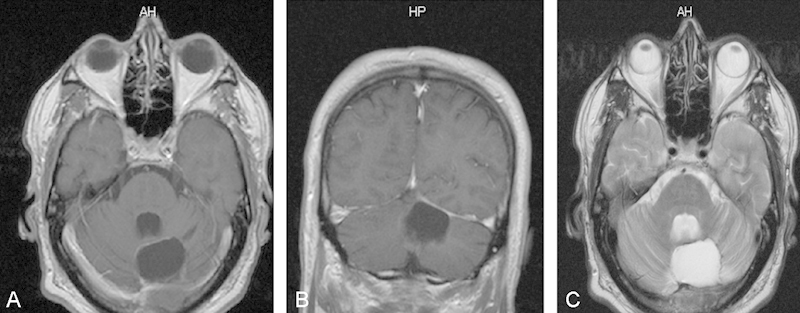

Postoperatively, the patient developed hydrocephalus and was treated with a third ventriculostomy. He recovered well and his cerebellar signs eventually resolved. He then underwent radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide beginning 24 days after surgery. Irradiation was delivered in a 54-Gy dose divided into 27 fractions. An MRI study of the brain with and without contrast 6 days after surgery confirmed radical tumor removal. The MRI was repeated every 3 months since and—1.5 years later—no evidence of tumor recurrence has been found (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

(A) Axial and (B) coronal T1-weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (C) T2-weighted axial MRI taken after surgery. Note the radical tumor removal in the left cerebellar hemisphere.

Discussion

GBM is the most common primary intracranial tumor in adults.2 4 9 19 20 Approximately two-thirds of the cases occur in adult patients, with a peak incidence around the sixth decade and a second peak in the first decade.9 16 21 22 23 The male-to-female ratio is 2:1.3 19 24 The main characteristic of GBM is a diffuse and infiltrative growth that follows white-matter pathways, even through the corpus callosum.4 16 The prognosis for patients with GBM remains poor despite multimodality treatment involving surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.6 16 21 25

Cerebellar GBMs

The scarcity of cerebellar GBMs is unexplained.1 3 25 One would anticipate these tumors to arise in the cerebellar location at a rate of ∼ 10% because the weight of the cerebellum is 10% of the weight of the whole brain.12 22 24 Cerebellar GBMs spread quickly and have a poor prognosis. Adults with an infratentorial GBM have a median overall life expectancy of ∼ 10 months, with a 1-year life expectancy of 38%.5 8 11 12 16 In children, the prognosis is also poor, with a mean survival time of 10 months.6 Primary cerebellar GBMs are exceedingly rare in childhood, with only ∼ 20 cases having been reported.3 6 7 12 26 The diagnosis of a GBM of the cerebellum is not usually suspected preoperatively, but certain features on CT and MRI studies may indicate a GBM.8 9 19 21 Cerebellar metastasis and anaplastic astrocytoma are the common differential diagnoses in adults.5 7 19 23 Ependymomas, or even extra-axial tumors such as vestibular schwannomas, may also be in the differential diagnosis.2 11 25 Surgical resection or stereotactic biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis.18 21 22

Like other glial lesions, cerebellar GBMs do not present in any specific way. The pattern of presentation depends on the site of the tumor and its speed of spread to the posterior fossa.11 13 14 Patients often have headaches, signs of increased intracranial pressure, and cerebellar signs including cerebellar ataxia, an inability to perform a tandem gait, dysmetria, and dysdiadochokinesia.3 8 10 11 12 13 14 16 The duration of symptoms before presentation varies from 1 to 4 months, a period significantly shorter than that of the more common tumors of the posterior fossa, which tend to have a longer history before presentation.9 23 25 26

GBMs of the cerebellum may also occur and present in atypical ways.4 18 27 One case reported in the literature describes the development of a cerebellar GBM after surgery for a medulloblastoma.26 Radiation therapy as a contributory or causative factor of GBM has also been suggested, and one cerebellar GBM occurred after irradiation of a cerebellar astrocytoma.27 One case report describes a cerebellar GBM in a patient diagnosed earlier with neurofibromatosis type I.2

Hypertensive Cerebellar Hemorrhage and GBM

Long-standing hypertension with degenerative changes in the vessel walls and subsequent rupture is believed to be the most common cause of a typical cerebellar hemorrhage.10 13 28 Blood dyscrasias, amyloid angiopathy, arteriovenous malformations, trauma, and sympathomimetic abuse are less common causes of cerebellar hemorrhage. Cerebellar hemorrhages have been reported to be rare in patients after supratentorial or spinal surgery and in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension.18 29 30 The location of the hemorrhage is important in determining the symptoms and clinical course, and the location may be more important than the absolute hematoma size for prognosis.13 30 31 Generally speaking, the more lateral the hemorrhage and the smaller the hematoma, the more likely the brainstem structures are spared and the better the prognosis. Brainstem damage by compression from an expanding mass in the posterior fossa is a common and feared complication.18 28 30

Suprasellar GBMs have a known propensity for bleeding.11 32 Furthermore, as noted earlier, cerebellar hypertensive hemorrhage is frequently encountered in neurosurgical practice. In our review of the English-language literature, however, we were unable to find a hypertensive cerebellar hemorrhage as the presenting entity of a GBM. Based on our experience, hypertensive cerebellar hemorrhage may disguise an underlying cerebellar GBM, and awareness of this possibility may avoid delay in diagnostics and treatment.

Based on their clinical and neuroradiologic presentations, cerebellar hypertensive hematomas are treated surgically (external ventricular drainage to resolve hydrocephalus, surgical removal of a blood clot, or both) or with observation and repeated CT scans until blood resorption is documented. Careful control of blood pressure with medication titration is recommended.10 18 28 30

Conclusion

A cerebellar GBM is a very rare clinical entity. Hypertensive cerebellar hemorrhage may be the first presentation of an underlying tumor, specifically a GBM. Based on our experience with this patient, we recommend that patients who undergo surgery for a cerebellar hypertensive hemorrhage should have the removed blood clots sent for careful histologic examination to rule out the possibility of an underlying tumor (including GBM). They should then be followed with pre and postcontrast MRI studies. Patients with cerebellar bleeding who are followed conservatively and do not undergo surgical removal of the blood clot should have a pre- and postcontrast MRI study done immediately after the hematoma resolves to prevent any potential delay in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Andrew J. Gienapp for technical and copy editing, preparation of the manuscript and figures, and publication assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure The authors have no sources of financial support to disclose.

References

- 1.Aun R A Stavale J N Silva Junior D Glioblastoma multiforme of the cerebellum. Report of a case [in Portuguese]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1981393350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broekman M L Risselada R Engelen-Lee J Spliet W G Verweij B H Glioblastoma multiforme in the posterior cranial fossa in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I Case Rep Med 2009;2009:757898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gusnard D A. Cerebellar neoplasms in children. Semin Roentgenol. 1990;25(3):263–278. doi: 10.1016/0037-198x(90)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai P H, Ho J T, Chen W L. et al. Brain abscess and necrotic brain tumor: discrimination with proton MR spectroscopy and diffusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(8):1369–1377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller E M, Mani R L, Townsend J J. Cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme in an adult. Surg Neurol. 1976;5(6):341–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pombo R Tortelly-Costa A Bulacio E Hahn M D de Carvalho M L Cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme: report of a case in a child [in Portuguese]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1985431102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ushio Y, Arita N, Yoshimine T, Ikeda T, Mogami H. Malignant recurrence of childhood cerebellar astrocytoma: case report. Neurosurgery. 1987;21(2):251–255. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198708000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zito J L, Siva A, Smith T W, Leeds M, Davidson R. Glioblastoma of the cerebellum. Computed tomographic and pathologic considerations. Surg Neurol. 1983;19(4):373–378. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(83)90248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Law M, Cha S, Knopp E A, Johnson G, Arnett J, Litt A W. High-grade gliomas and solitary metastases: differentiation by using perfusion and proton spectroscopic MR imaging. Radiology. 2002;222(3):715–721. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2223010558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirsen T. Acute treatment of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12(6):504–517. doi: 10.1007/s11940-010-0096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inamasu J, Kuramae T, Nakatsukasa M. Glioblastoma masquerading as a hypertensive putaminal hemorrhage: a diagnostic pitfall. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2009;49(9):427–429. doi: 10.2176/nmc.49.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulkarni A V, Becker L E, Jay V, Armstrong D C, Drake J M. Primary cerebellar glioblastomas multiforme in children. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(3):546–550. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.3.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurita M, Endo M, Kitahara T, Fujii K. Subarachnoid haemorrhage due to a lateral spinal artery aneurysm misdiagnosed as a posterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm: case report and literature review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151(2):165–169. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0183-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenfeld J, Rossi M L, Briggs M. Glioblastoma multiforme of the cerebellum in an elderly man. A case report. Tumori. 1989;75(6):626–629. doi: 10.1177/030089168907500623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsung A J, Prabhu S S, Lei X, Chern J J, Benjamin Bekele N, Shonka N A. Cerebellar glioblastoma: a retrospective review of 21 patients at a single institution. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(3):555–562. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0617-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vertosick F T Jr Selker R G Brain stem and spinal metastases of supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme: a clinical series Neurosurgery 1990274516–521.; discussion 521–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber D C, Miller R C, Villà S. et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme in adults: a retrospective study from the Rare Cancer Network. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(1):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafar A, Khan F S. Clinical and radiological features of intracerebral haemorrhage in hypertensive patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58(7):356–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilaniuk L T. Adult infratentorial tumors. Semin Roentgenol. 1990;25(2):155–173. doi: 10.1016/0037-198x(90)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demir M K, Hakan T, Akinci O, Berkman Z. Primary cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11(2):83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopelson G. Cerebellar glioblastoma. Cancer. 1982;50(2):308–311. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820715)50:2<308::aid-cncr2820500224>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroiwa T, Numaguchi Y, Rothman M I. et al. Posterior fossa glioblastoma multiforme: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16(3):583–589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Occhiogrosso M, Spada A, Merlicco G, Vailati G, De Benedictis G. Malignant cerebellar astrocytoma. Report of five cases. J Neurosurg Sci. 1985;29(1):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luccarelli G. Glioblastoma multiforme of the cerebellum: description of three cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1980;53(1-2):107–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02074526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegedüs K, Molnár P. Primary cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme with an unusually long survival. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1983;58(4):589–592. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.4.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidbauer M, Budka H, Bruckner R, Vorkapic P. Glioblastoma developing at the site of a cerebellar medulloblastoma treated 6 years earlier. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(6):915–918. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.6.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wisoff H S, Llena J F. Glioblastoma multiforme of the cerebellum five decades after irradiation of a cerebellar tumor. J Neurooncol. 1989;7(4):339–344. doi: 10.1007/BF02147091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y T, Hsieh M F, Chu H Y, Lu S C, Chang S T, Li T Y. Recurrent cerebellar hemorrhage: case report and review of the literature. Cerebellum. 2010;9(3):259–263. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jao T, Liu H M, Tang S C, Jeng J S. Dissection of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery in a young adult with cerebellar infarct. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2008;17(4):243–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lekic T, Tang J, Zhang J H. Rat model of intracerebellar hemorrhage. Acta neurochirurgica Suppl. 2008;105:131–134. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-09469-3_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asato R, Okumura R, Konishi J. “Fogging effect” in MR of cerebral infarct. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15(1):160–162. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199101000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim Y J, Lee S K, Cho M K, Kim Y J. Intraventricular glioblastoma multiforme with previous history of intracerebral hemorrhage: a case report. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;44(6):405–408. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.44.6.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]