Abstract

Background and Aims

The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are widely prescribed for patients with hyperlipidemia and are generally well tolerated. Mild elevations in serum aminotransferases arise in up to 3% of treated patients, but clinically apparent drug induced liver injury is rare. The aim of this study is to report the presenting features and outcomes of 22 patients with clinically apparent liver injury due to statins.

Methods

Among 1188 cases of drug-induced liver injury enrolled between 2004 and 2012 in a prospective registry by the U.S. Drug Induced Liver Injury Network, 22 were attributed to a statin. All patients were evaluated in a standard fashion and followed for at least 6 months after onset.

Results

The median age was 60 years (range 41 – 80), and 15 (68%) were female. The latency to onset of liver injury ranged from 34 days to 10 years (median =155 days). Median peak levels were ALT 892 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 358 U/L and total bilirubin 6.1 mg/dL. Nine patients presented with cholestatic hepatitis and 12 patients presented with hepatocellular injury of which 6 had an autoimmune phenotype. Nine patients were hospitalized, 4 developed evidence of hepatic failure and 1 died. All commonly used statins were implicated. Four patients developed chronic liver injury of which three had an autoimmune phenotype of liver injury.

Conclusion

Drug induced liver injury from statins is rare and characterized by variable patterns of injury, a range of latencies to onset, autoimmune features in some cases, and persistent or chronic injury in 18% of patients most of whom have an autoimmune phenotype.

Introduction

The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are among the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide with over 143 million prescriptions annually dispensed in the United States alone (1). Statins reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in high risk patients with hyperlipidemia (2, 3). They are also generally well tolerated, although dose dependent adverse events, including myositis and myalgias develop in 10% to 15% of patients (4). In addition, up to 3% of patients develop mild serum aminotransferase elevations within the first year of therapy, but these elevations are rarely associated with symptoms and often resolve even with continued treatment (4, 5).

Clinically apparent drug induced liver injury attributed to statins has been reported but appears to be rare. A systematic review of the literature published in 2009 identified only 40 cases of statin hepatotoxicity mostly from single case reports and no case series with more than 4 patients (6). The U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group reported 6 cases of acute liver failure attributed to statins among a total 131 cases of acute liver failure due to drugs other than acetaminophen over a 10 year period (7). In a 2-year, population-based study from Iceland only 3 cases of liver injury from statins were identified (8). In an analysis of 12 years of adverse drug reaction reports to a Swedish registry, 73 cases of liver injury attributed to statins were identified, 34% of which were jaundiced and 4% fatal (9). Although there is substantial literature on statin-induced liver injury, the systematic evaluation and exclusion of other liver diseases, details on dose and duration of therapy and long term follow-up on recovery are lacking.

The U.S. Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) is an ongoing multicenter, prospective study of the etiologies and outcomes of liver injury due to drugs, herbal medications or dietary supplements in the United States. In addition to carefully characterizing the presenting clinical features of liver injury due to medications, DILIN collects biological samples for mechanistic studies of pathogenesis (10, 11). The current study provides detailed information on the presentation and course of 22 cases of statin-induced liver injury which underwent expert adjudication and standardized collection of clinical data, laboratory tests, and when available liver biopsy findings.

Methods

The U.S. DRUG-INDUCED LIVER INJURY Network (DILIN)

DILIN established a prospective registry in September 2004 wherein patients were enrolled with suspected liver injury due to any known drug, herbal or dietary supplement (10, 11). Detailed descriptions of the purpose and design of DILIN and its process of causality assessment have been published (10). Briefly, after providing written informed consent, patients underwent a medical history and physical examination, including review of the dates, doses, and indications for the suspect drug and other concomitant medications. Common causes of liver injury were excluded such as viral hepatitis, alcohol, pancreatic, biliary, and metabolic liver disease. All subjects had to meet predefined laboratory entry criteria, and were followed for at least 6 months to help exclude other diagnoses. Testing of stored specimens for acute hepatitis E virus infection was undertaken as previously described (12). Additionally, a Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score was assigned to each case (13). To be included in the present analysis, the case had to be adjudicated by expert opinion as definite [95-100% likelihood], very likely [75-94% likelihood] or probable [51-74% likelihood]. In cases where multiple drugs were implicated, the statin had to have the highest causality score. Each case was assigned a severity score of 1 to 5, in which 1 indicated serum enzyme elevations without jaundice; 2, serum enzyme elevations and jaundice; 3, jaundice and hospitalization for liver injury; 4, jaundice with signs of hepatic or other organ failure; and 5, death from liver disease or liver transplantation within 6 months of onset. Chronic injury was defined as liver biochemical or histological abnormalities that persisted for 6 months or more after onset (10).

Liver Histopathology

Available liver biopsies were formally interpreted by the study pathologist (DEK) who was blinded to all clinical information. A full description of the methods and scoring systems used has recently been published (14). Features of autoimmune liver injury were specifically sought, including interface hepatitis, portal mononuclear cell infiltrates, plasma cells and focal necrosis.

Data Analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data including means and standard deviations (SD), medians, and ranges for continuous variables; and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests (or Fisher exact test for situations with small frequencies) and non-parametric tests were used to test the difference between injury types for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. A p value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All calculations were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics and presenting features

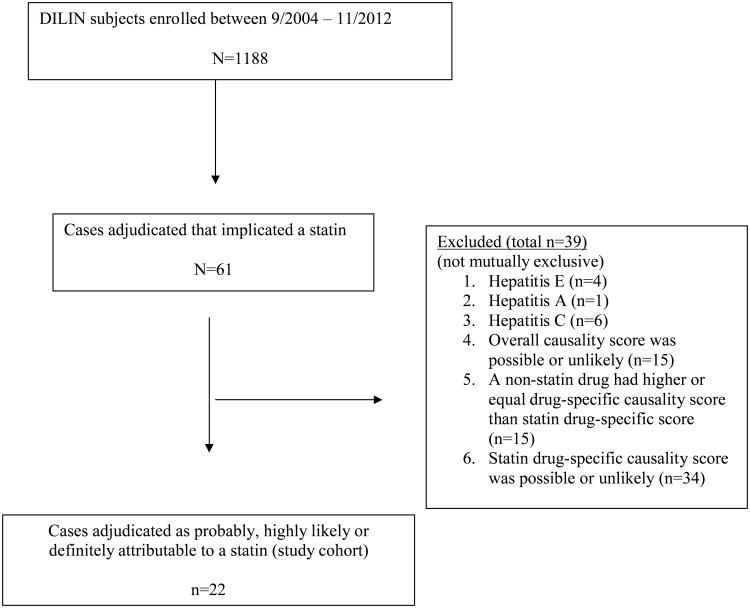

Between September 2004 and November 2012, 1188 patients with suspected drug-induced liver injury were enrolled into the DILIN prospective registry. Statins were initially implicated in 61 cases (6%), but upon formal review only 22 were adjudicated as definitely (n=2), highly likely (n=9) or probably (n=11) attributable to the statin (Figure 1). In 15 of the 22 cases a statin was the only implicated drug, whereas in the remaining 7 another drug(s) was also implicated but considered less likely as a cause. The 39 excluded cases included 11 which were later found to be due to viral hepatitis and 28 others in which the injury were judged as unlikely or only possibly due to the statin, other agents or other diagnoses being considered more likely (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

The 22 patients with statin induced liver injury ranged in age from 41 to 80 years (median = 60 years), 15 (68%) were women and 18 (82%) were non-Hispanic whites (Table 1). The average body mass index was 25 kg/m2 and 7 (32%) patients had diabetes. One subject was known to have pre-existing alcoholic liver disease with portal hypertension and compensated cirrhosis; this case being the only one with a fatal outcome.

Table 1. Clinical Features in 22 cases of Statin-Induced Liver Injury.

| Clinical Feature | Median or Number | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 60 | 41 - 80 |

| Female sex | 15 (68%) | |

| White race | 18 (82%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24 | 19 - 38 |

| Onset <12 weeks | 6 (27%) | |

| Onset 12-24 weeks | 6 (27%) | |

| Onset >24 weeks | 10 (45%) | |

| Jaundice | 15 (68%) | |

| Itching | 8 (36%) | |

| Rash | 4 (18%) | |

| Fever (by history) | 5 (23%) | |

| Initial ALT (U/L)* | 892 | 73 - 3074 |

| Initial Alk P (U/L)* | 338 | 79 - 1952 |

| Initial R ratio | 8.7 | 0.4 - 37 |

| Initial bilirubin (mg/dL)* | 3.9 | 0.3 - 18 |

| Peak bilirubin (mg/dL)* | 6.1 | 0.6 - 34 |

| Peak INR (SD) | 1.2 | 0.9 - 5.2 |

| ANA (≥1:40) | 8 (22%) | |

| SMA (≥1:40) (n=21) | 8 (38%) | |

| Severity score* | ||

| Mild (1+) | 7 (32%) | |

| Moderate (2+) | 7 (32%) | |

| Moderate Hospitalized (3+) | 4 (18%) | |

| Severe (4+) | 3 (14%) | |

| Fatal (5+) | 1 (4%) | |

| Liver transplant | 0 | |

| chronic injury at 6 months | 4 |

Median.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Alk P, alkaline phosphatase; INR, international normalized ratio.

Of the 22 patients, 19 presented with clinical symptoms and 3 were asymptomatic, the liver injury being detected based upon routine liver tests. Fifteen (68%) patients were jaundiced (total bilirubin ≥ 2.5 mg/dL) and four (18%) had elevations in serum INR (>1.5). Fever was reported by 5 subjects at presentation and rash in 4 but these manifestations of immuno-allergic injury were not prominent and no patient had a peripheral eosinophil count of more than 500 cells/μL. Eleven (50%) patients were reactive for at least one autoantibody including ANA in 8, SMA in 5 and AMA in 2 cases, but titers were usually modest and were 1:160 or greater in only 4 patients.

The implicated statins included atorvastatin (n=8), simvastatin (n=5), rosuvastatin (n=4), fluvastatin (n=2), pravastatin (n=2) and lovastatin (n=1). The daily dose was within the recommended range in all patients and the median dose was 20 mg daily (Table 2).

Table 2. Selected Demographic, lab, and clinical features of 22 cases of statin-related liver injury.

| Case | Statin | Age | Sex | DILIN causality score |

RUCAM Score |

Daily Dose (mg) |

Time to Onset* (mo) |

Peak ALT (U/L) |

Peak Alk P (U/L) |

Peak Bilirubin (mg/dL) |

Pattern | Outcome | Severity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atorvastatin | 70 | F | 2 | 9 | 20 | 2.8 | 222 | 665 | 1.0 | HC | Resolved | 1 |

| 2 | Atorvastatin | 65 | F | 1 | 9 | 80 | 4.1 | 666 | 861 | 1.0 | HC | Resolved | 1 |

| 3 | Atorvastatin | 80 | F | 3 | 8 | 80 | 2.2 | 504 | 1952 | 18.8 | Chol | Resolved | 4 |

| 4 | Atorvastatin | 54 | M | 2 | 7 | 40/80 | 5.2 [0.5] | 502 | 200 | 5.2 | Chol | Resolved | 2 |

| 5 | Atorvastatin | 71 | M | 3 | 8 | 10 | 41.6 | 3074 | 362 | 22.3 | HC-AI-P | Resolved | 4 |

| 6 | Atorvastatin | 64 | F | 2 | 5 | 80 | 5.7 | 1490 | 529 | 4.2 | HC | Resolved | 2 |

| 7 | Atorvastatin | 61 | F | 3 | 12 | 20/40 | 62.2 | 4560 | 512 | 30.2 | HC-AI-P | Resolved | 4 |

| 8 | Atorvastatin | 78 | F | 2 | 8 | 10 | 120 | 1117 | 1006 | 17.0 | Chol | Resolved | 3 |

| 9 | Fluvastatin | 77 | F | 3 | 7 | 80 | 37 | 1260 | 188 | 0.8 | HC-AI | Chronic | 1 |

| 10 | Fluvastatin | 52 | F | 1 | 6 | 80 | 1.7 | 370 | 208 | 8.3 | Chol | Resolved | 2 |

| 11 | Lovastatin | 80 | F | 3 | 5 | 50 | 5.1 | 177 | 724 | 20.2 | Chol | Resolved | 2 |

| 12 | Pravastatin | 53 | F | 3 | 6 | 20 | 11.6 | 486 | 95 | 0.38 | HC-AI | Chronic | 1 |

| 13 | Pravastatin | 50 | M | 2 | 8 | 20/40 | 7.2 [1] | 2370 | 234 | 6.9 | HC | Resolved | 2 |

| 14 | Rosuvastatin | 64 | F | 2 | 8 | 20 | 4.5 | 1119 | 399 | 1.3 | HC | Resolved | 1 |

| 15 | Rosuvastatin | 59 | F | 3 | 8 | 10 | 25.8 | 275 | 526 | 3.5 | Chol | Chronic | 3 |

| 16 | Rosuvastatin | 58 | F | 3 | 8 | 20 | 2.8 | 2583 | 184 | 16.4 | HC-AI-P | Chronic | 3 |

| 17 | Rosuvastatin | 52 | F | 3 | 8 | 10 | 2.0 | 1506 | 235 | 1.7 | HC | Resolved | 1 |

| 18 | Simvastatin | 67 | M | 3 | 6 | 40 | 5 | 145 | 142 | 33.5 | AoC | Died | 5 |

| 19 | Simvastatin | 51 | M | 2 | 9 | 10 | 9.4 | 307 | 538 | 3.1 | Chol | Resolved | 2 |

| 20 | Simvastatin | 41 | F | 2 | 6 | 20 | 7.5 | 1778 | 354 | 20.3 | HC | Resolved | 2 |

| 21 | Simvastatin | 43 | M | 3 | 6 | 20 | 6.7 | 587 | 121 | 0.6 | HC | Resolved | 1 |

| 22 | Simvastatin | 50 | M | 3 | 8 | 40 | 1.5 | 3336 | 348 | 20.9 | HC-AI | Resolved | 3 |

Abbreviations: see Table 1; HC, hepatocellular; Chol, cholestatic; AI, autoimmune features; P, treatment with prednisone.

Time after dose increase given in brackets

The latency (time from starting statin to onset of liver injury) varied widely. Using the time to initial identification of abnormal liver tests as a definition, latency ranged from 34 days to more than 10 years with a mean of 464 and a median of 155 days. The latency was 1 to 3 months in 6 (27%), 3 to 6 months in 6 (27%), 6 to 12 months in 5 (23%) and greater than a year in the remaining 5 (23%). No patient developed drug-induced liver injury within 4 weeks of starting the statin (Table 2). Three patients had previous exposure to the same statin, 4 were previously exposed to a different statin and two patients had a dose increase within a few months of developing liver injury. Of the 17 cases with available information on concomitant medications, 10 (59%) were taking three or more medications.

Hepatitis E (HEV) testing was available for 20 cases (12). Four (20%) cases had anti-HEV IgG, but none of the four had IgM anti-HEV. HEV RNA testing was only done on one of the four and was negative. Two patients with anti-HEV were tested somewhat late in their course (5.3 and 9.5 months after onset). In these two patients, IgG anti-HEV levels did not change significantly over the next 6 months (one increased slightly, one decreased slightly). All 22 cases were anti-HCV negative. Only 12 were tested for HCV RNA and all were negative.

Phenotypes of Statin-Induced Liver Injury

The clinical phenotype of liver injury also varied widely but could be broadly categorized as either hepatocellular or cholestatic. For this categorization, the one fatal case was excluded, because the clinical presentation was with worsening jaundice and hepatic failure with little change in serum enzyme elevations (acute-on-chronic liver failure) and could not be categorized as either cholestatic or hepatocellular. The remaining 21 cases included 12 that were hepatocellular and 9 cholestatic (Table 3). The categorization was based usually upon the initial ratio (R ratio) of serum ALT to alkaline phosphatase, both expressed as multiples of the upper limit of the normal range: those with an R >5 being hepatocellular and those <2 being cholestatic. Two patients had an initial R value between 2 and 5 and were thus “mixed”, but R values subsequently decreased in both and both had jaundice and pruritus typical of cholestatic liver injury.

Table 3. Clinical Phenotypes in Statin-Associated Liver Injury.

| Clinical Feature | Hepatocellular (n=12) | Cholestatic (n=9) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 57 (±10.8) | 65 (±11.9) | 0.12 |

| Female sex | 67% | 78% | 0.66 |

| White race | 75% | 89% | 0.47 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26.1 (±2.8) | 23.7 (±4.1) | 0.18 |

| Onset <12 weeks | 12% | 50% | 0.27 |

| Onset 12-24 weeks | 25% | 25% | |

| Onset > 24 weeks | 63% | 25% | |

| Jaundice | 75% | 56% | 0.40 |

| Itching | 25% | 44% | 0.40 |

| Rash | 25% | 11% | 0.60 |

| Initial ALT (U/L)** | 1634 (486-3074) | 307(177-1117) | <0.001 |

| Initial Alk P (U/L)** | 228 (79-529) | 665 (199-1952) | 0.004 |

| Initial R ratio** | 19.2 (5.9-36.7) | 1.6 (0.4-4.1) | <0.001 |

| Initial bilirubin (mg/dL)** | 4.7 (0.3-18.4) | 4.3 (0.4-12.2) | 0.89 |

| Peak bilirubin (mg/dL)** | 5.6 (0.6-30.2) | 5.2 (1.0-20.2) | 0.94 |

| Peak INR** | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 1.1 (1.0-2.7) | 0.94 |

| ANA | 58% | 11% | 0.07 |

| SMA† | 45% | 22% | 0.37 |

| Severity score ** | 3 (2-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.78 |

| Death π | 0% | 0% | 1.00 |

| Liver transplant | 0% | 0% | 1.00 |

| Chronic injury at 6 mos | 25% | 11% | 0.63 |

RUCAM scores for the 22 cases ranged from 5 to 12 and comparison to DILIN causality scores showed reasonable comparability (Supplementary Table 2). All cases were scored by RUCAM in the range considered to be “highly probable” (9-12: n=4) or “probable” (6-8: n=16) except for two cases that were scored by RUCAM as “possible” (5: n=2) but as probable (Case #11) and highly likely (case #6) by expert opinion (Table 1).

Comparisons of hepatocellular and cholestatic cases of statin-induced liver injury showed that the hepatocellular cases tended to be younger (mean age 57 vs 65 years), but did not differ by type of statin, distribution of latencies, gender, body mass index (BMI) or disease severity (Table 3).

The 12 hepatocellular cases were further categorized as having prominent autoimmune features or not. Thus, 6 of the 12 had high levels of autoantibodies (ANA or ASMA >1:80) or a liver biopsy suggesting autoimmune hepatitis or both (Table 4). Comparisons indicated that patients with autoimmune features were more likely to develop evidence of chronic injury and more likely to receive corticosteroids. Indeed, two cases (cases 7 and 16) of the 6 patients with the autoimmune phenotype still had evidence of active disease more than 6 months after onset and received courses of prednisone. Case 7 was treated with prednisone for 7 months and azathioprine was added 3 months after starting the prednisone. The patient remained on azathioprine 10 months after stopping atorvastatin. Case 16 was treated with prednisone and liver tests normalized 5 months after stopping rosuvastatin and starting prednisone. After 5 months prednisone was stopped and liver enzymes increased and prednisone was restarted with persistent elevation in liver enzymes 2 months after restarting prednisone (7 months after stopping rosuvastatin).

Table 4. Hepatocellular Phenotypes in Statin-Associated Liver Injury.

| Clinical Features | Autoimmune (n=6) | Typical (n=6) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 62 (±10.3) | 53 (±9.8) |

| Female sex | 67% | 67% |

| White race | 66% | 83% |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 27.9 (±5.7) | 24.3(±2.8) |

| Latency to onset | ||

| <12 weeks | 33% | 0 |

| 12-24 weeks | 0% | 25% |

| 24-48 weeks | 16% | 75% |

| >1 year | 50% | 0 |

| Jaundice | 67% | 83% |

| Itching | 33% | 17% |

| Rash | 17% | 33% |

| Fever | 33% | 17% |

| Initial ALT (U/L)** | 2382(486-3074) | 1437(587-2370) |

| Initial Alk P (U/L)** | 240(479-446) | 274(121-529) |

| Initial R ratio** | 22.4(15-37) | 17.6(5.9-23.4) |

| Initial bilirubin (mg/dL)** | 7.8(0.3-18.4) | 2.8(0.6-17.8) |

| Peak bilirubin (mg/dL)** | 17.3(0.6-30.2) | 3.0(0.7-20.3) |

| Peak INR** | 1.3(1.0-1.6) | 1.1(0.9-1.2) |

| ANA (≥ 1:40) | 67% | 50% |

| SMA (≥ 1:40) | 67% | 20% |

| Death | 0% | 0% |

| Liver Transplant | 0% | 0% |

| Chronic injury at 6 mos | 50% | 0% |

Results given as proportions unless otherwise designated

Mean (standard deviation).

Median (range)

Abbreviations: see Table 1.

None of the above differences were statistically significant

Details of the clinical history, laboratory results and outcome of representative examples of the different phenotypes of statin-induced injury are given as supplementary material, including cases of cholestatic injury with or without complete resolution, hepatocellular injury with or without autoimmune features and with or without complete resolution. The single fatal case of acute-on-chronic liver failure is also described.

Histology

Eight subjects underwent liver biopsy. Three subjects with cholestatic liver injury (cases 3, 10, 19), three with hepatocellular-autoimmune (cases 5, 7, 16), one patient with hepatocellular pattern only (case 17) and the fatal case of acute-on-chronic injury (case 18) underwent liver biopsy. Four liver biopsies (cases 3, 5, 10 and 16) showed cholestatic hepatitis, with hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis and bile duct injury combined with portal and lobular inflammation. Three cases (3, 5 and 16) had features suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis with a moderate to severe lymphocytic hepatitis with plasma cell (two had serum autoantibodies). The remaining cases did not have features suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis and only case 16 had increased numbers of eosinophils. Confluent necrosis was seen in 4 cases and was the dominant injury in case 17, in which clear zone 3 necrosis with inflammation was present. In the fatal case (case 18), steatohepatitis with Mallory bodies, microvesicular steatosis and extensive perisinusoidal fibrosis was also present along with the cholestasis. Steatosis was a common finding (5 of 8 biopsies) and probably represented pre-existing fatty liver disease. In 2 of the 5 cases with steatosis, there were many cells with a foamy appearance consistent with microvesicular steatosis.

Discussion

The statins were originally thought to have a high potential for causing drug-induced liver injury. When first approved for use in the United States, routine monitoring of serum enzyme levels at monthly intervals was recommended. Subsequently, however, the frequency of serum aminotransferase elevations during long-term use of statins was found to be only slightly greater than occurs with placebo treatments, and these abnormalities rarely resulted in clinically apparent liver injury. In this prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States, statins were initially implicated in 61 cases, but careful adjudication found only 22 (36%) could be considered convincing (more than 50% likelihood). All of the major statins were implicated at rates similar to their relative use in the United States (1). Perhaps, the most striking finding in this study is the lack of a single distinctive phenotype of liver injury cause by statins. Both mild and severe, short and long latency, and very cholestatic and very hepatocellular cases were found and the clinical features did not correlate with type of statin or conventional clinical demographics of patients. As with many other drugs, hepatocellular injury was more common among younger patients but there was considerable overlap. Time to onset, severity and outcome did not seem to correlate with any clinical phenotype or specific implicated statin. For unclear reasons histology did not correlate with biochemical classification, however, the timing of the biopsy was often late in the course whereas the biochemical classification was usually based upon the laboratory findings at onset, and in addition many subjects did not have a biopsy.

A striking feature of some cases of statin-induced liver injury was the prolonged latency. Indeed, 5 of the 22 patients had been taking the agent for a year or more before onset of acute injury. This prolonged time to onset is unusual, in that most cases of drug-induced liver injury present within 6 months. Furthermore, drugs typically associated with a long latency (nitrofurantoin, minocycline, or methyldopa) usually present with a chronic hepatitis-like syndrome rather than an acute hepatocellular or cholestatic hepatitis. Prolonged latency was seen with most of the types of statins (atorvastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, rosuvastatin) presenting with both hepatocellular and cholestatic patterns of liver injury. Although cases with long latency are unusual, we systematically excluded other causes of liver disease and liver test elevations resolved with discontinuation of the statin. Cases of long latency to onset of liver injury from statins have been described before, but many case series lack any instances with a latency of above a year, perhaps because such cases are excluded or considered less than probably related (6, 9).

A proportion of subjects with statin associated liver injury developed features of autoimmune hepatitis, with ANA or SMA positivity, raised serum immunoglobulin levels and/or autoimmune hepatitis-like histology. All cases had a hepatocellular pattern of injury and a high proportion received systemic corticosteroid therapy. Importantly, 2 of the 6 cases appeared to have self-sustained autoimmune hepatitis with persistently elevated serum enzymes that required immunosuppressive therapy when last seen, more than six months after initial onset. This pattern differs from the autoimmune hepatitis like injury that is associated with minocycline and nitrofurantoin which typically resolves after the drug is discontinued, and in which immunosuppressive therapy can ultimately be stopped. One interpretation of these findings is that the liver injury was coincidental and unrelated to the statin use, which might not be unexpected given the frequency of long-term statin use in the general population. On the other hand, many of these cases did resolve once statins are discontinued and those that required long-term immunosuppressive therapy improved to a certain extent upon stopping the drug. Another interpretation is that statins may trigger autoimmune hepatitis in a susceptible patient, which may become self-sustaining, if the statin was not stopped promptly or the injury was particularly severe. Similar cases of self-sustained autoimmune hepatitis seemingly triggered by statin exposure have been reported (15, 16). Importantly, among the cases with hepatocellular injury without serum autoantibodies in the current series none developed chronic injury. Thus, the presence of autoantibodies in patients with drug induced liver from statins may identify those at increased risk for chronic injury. Although, the clinical importance of chronic injury from drugs is unknown, it seems prudent to recommend that such subjects continue to be followed for additional evidence of chronic liver disease.

While four of the 22 cases of statin-induced liver injury were considered severe and one patient died, the liver injury was largely mild-to-moderate in severity and self-limited in course. The one patient who died had pre-existing alcoholic cirrhosis and esophageal varices and the other 3 cases that were scored as severe had a transient prolongation of the prothrombin time (INR >1.5) only, without hepatic encephalopathy, ascites or fluid overload. The fatal case was adjudicated as probable (3) because the underlying alcoholic liver disease was thought to have contributed to his death. Thus, statin-induced liver injury is usually mild-to-moderate in severity and fairly rapidly reversed in most cases once the agent is stopped.

The current results could not address the question of whether there is cross-reactivity among the different statins in susceptibility to liver injury. One patient was restarted on the same statin and rapidly redeveloped acute injury. Four patients had received another statin previously without hepatic injury, but none of the 22 patients in this series was switched to another statin and monitored. In this regard, previous studies have presented conflicting results, with most instances not re-developing hepatic injury when another statin was started [9, 17-21]. However, because rare instances of recurrence of hepatotoxicity after switching to another statin have been reported, switching should be done with caution and with careful monitoring [6, 22].

In summary, the current case series suggests that clinically apparent liver injury from the statins is likely a class effect and can arise many months and sometimes years after initiation. Statin-induced liver injury has variable clinical presentations including distinctly cholestatic, markedly hepatocellular and even autoimmune hepatitis-like phenotypic manifestations. Liver injury from statins is rare, usually mild-to-moderate in severity, and rapidly reversed upon stopping, although cases with an autoimmune phenotype of liver injury were more likely to develop evidence of chronic injury. Based on these data, prospective monitoring for drug induced liver injury from statins is not warranted, but patients who develop a liver injury with an autoimmune phenotype should be closely monitored and evaluated for immunosuppressive therapy if liver tests fail to improve.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Excluded cases

Supplementary Table 2: Comparison of RUCAM Score and DILIN Causality scores, with case numbers

Acknowledgments

DILIN is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases under the following cooperative agreements: 1UO1DK065201,1UO1DK065193,1UO1DKO65184,1UO1DK065211,1UO1DK065238, and 1UO1DK06F5176. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute

Abbreviations

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- AMA

antimitochondrial antibody

- ANA

antinuclear antibody

- DILI

Drug induced liver injury

- DILIN

Drug Induced Liver Injury Network

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SMA

smooth muscle antibody

- ULN

upper limit of normal

References

- 1. [accessed Jan 4, 2013]; www.drugtopics.com.

- 2.Serruys PW, De Feyter P, Macaya C, et al. Fluvastatin for prevention of cardiac events following successful first percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2002;287:3215–3222. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltowski J, Wojcicka G, Jamroz-Wisniewska A. Adverse effects of statins-mechanisms and consequences. Curr Drug Saf. 2009;4:209–28. doi: 10.2174/157488609789006949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalasani N. Statins and hepatotoxicity: Focus on patients with fatty liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:690. doi: 10.1002/hep.20671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo MW, Scobey M, Bonkovsky HL. Drug-induced liver injury associated with statins. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2009;29:412–422. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM the Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-Induced Acute Liver Failure: Results of a U.S. Multicenter, Prospective Study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Björsson ES, Bergmann OM, Bjornsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419–1425. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björnsson E, Jacbosen E, Kalaitzakis E. Hepatotoxicity associated with statins: Reports of idiosyncratic liver injury post-marketing. J Hepatol. 2012;56:374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontana RJ, Watkins PB, Bonkovsky HL, Chalasani N, Davern T, Serrano J, Rochon J. Drug induced Liver Injury Network (DRUG-INDUCED LIVER INJURYN) prospective study: rationale, design, and conduct. Drug Saf. 2009;l32:55–68. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932010-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkvosky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J. Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924–34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davern TJ, Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Hayashi PH, Protiva P, Kleiner DE, et al. Acute hepatitis E infection accounts for some cases of suspected drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1665–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs—I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323–30. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleiner DE, Chalasani N, Lee WM, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Hayashi PH, et al. Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hep.26709. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alla V, Abraham J, Siddiqui J, Raina D, Wu G, Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by statins. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:757–61. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. [accessed December 1, 2013]; www.livertox.nih.gov.

- 17.Nakad A, Bataille L, Hamoir V, Sempoux C, Horsman Y. Atorvastatin-induced hepatitis with the absence of cross-toxicity with simvastatin. Lancet. 1999;353:1763–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charles EC, Olson KL, Sandhoff BG, McClure DL, Merenich JA. Evaluation of cases of severe statin-related transaminitis within a large health maintenance organization. Am J Med. 2005;118:618–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perger L, Kohler M, Fattinger K, Flury R, Meier PJ, Pauli-Magnus C. Fatal liver failure with atorvastatin. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1095–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00464-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreenarasinhaiah J, Shiels P, Lisker-Melman M. Multiorgan failure induced by atorvastatin. Am J Med. 2002;113:348–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridruejo E, Mando OG. Acute cholestatic hepatitis after reinitiating treatment with atorvastatin. J Hepatol. 2002;37:165–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YW, Lai HW, Wang TD. Marked elevation of liver transaminases after high-dose fluvastatin unmasks chronic hepatitis C: safety and rechallenge. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2007;16:163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Excluded cases

Supplementary Table 2: Comparison of RUCAM Score and DILIN Causality scores, with case numbers