Abstract

We use matching combined with difference-in-differences to identify the causal effects of sudden illness, represented by acute hospitalizations, on employment and income up to six years after the health shock using linked Dutch hospital and tax register data. An acute hospital admission lowers the employment probability by seven percentage points and results in a five percent loss of personal income two years after the shock. There is no subsequent recovery in either employment or income. There are large spillover effects: household income falls by 50 percent more than the income of the disabled person.

I. Introduction

Increasing the economic activity of middle-aged and older individuals is considered essential to relieving the economic pressures generated by aging populations. Governments are striving to prune disability insurance rolls, discourage early retirement and raise the statutory retirement age. The effectiveness of these measures depends on the extent to which ill-health constrains the earnings capacity and employment opportunities of the 50+ population. Ill-health is frequently reported to be a leading cause of labor market withdrawal in middle-age (Bound et al. 1999; Currie and Madrian 1999; Dwyer and Mitchell 1999; French 2005; Disney, Emmerson, and Wakefield 2006). However, the existing evidence base to gauge whether improved population health, or at least reduced disability, alongside improved financial incentives, could increase labor market participation is weak or incomplete in three important respects.

First, most studies rely on subjective health measures, which will overestimate the impact on employment when disability is reported as justification for inactivity and health indicators used to instrument reported work incapacity are subject to the same reporting bias (Bound 1991). Second, the evidence mostly concerns the immediate, or one period hence, response of employment to illness or disability. Deterioration of health capital can be expected to result in an immediate loss of earnings capacity and employment opportunities. Less clear is whether there is recovery in the longer term through either the repair of health capital or its substitution with other human capital acquired by re-training for jobs less impeded by a chronic health impairment (Charles 2003). Third, while there is consensus that ill-health is an important determinant of the disabled person’s economic activity, there is little consistent evidence regarding the labor supply reponse of his or her spouse (Berger and Fleisher 1984; Blau and Riphahn 1999; Wu 2003). In theory, the effect is ambiguous. On the one hand, the spouse may substitute for the lost earnings of the disabled person - the classic added-worker effect (Mincer 1962). On the other, the spouse may reduce market activity in order to meet the care needs of the disabled person, or to increase joint leisure given reduced expectations of the latter’s remaining length of life. The evidence base on which of these effects dominates under what circumstances is woefully lacking.

We address all three of these limitations using particularly rich linked data from hospital admission records, income tax files and the municipality register containing socio-demographic information in the Netherlands for an eight-year period. To circumvent the health reporting problem and to exploit health variation that is more objective and arguably exogenous to trends in labor market outcomes by virtue of being unexpected, we identify from unscheduled and urgent hospital admissions of individuals aged between 18 and 64 who had not been admitted in the previous year. By using registered admissions and conditioning on employment at the time of admission, we avoid problems of reverse causality. We take account of observable differences between employed individuals with and without an acute admission by matching using propensity scores and combine this with difference-indifferences (DiD) regression to correct for any selection on time invariant unobservables (Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd 1997).

Labor market outcomes are observed from the tax files traced for up to six years after admission. This extended follow-up provides a rare opportunity to observe how employment and income evolve from the period immediately following the health shock to the longer term during which health may recover, re-training may facilitate adaption to any persistent disability or health may deteriorate further. Incentives to recover health and to invest in skills compatible with residual disability will vary with individual characteristics and are conditional on the disability insurance system, which in the Netherlands was among the most generous anywhere in the world until reforms made in the last decade. Older individuals are likely to experience both a greater loss of health capital and, with lower remaining working life expectancy, have less incentive to invest in re-training (Charles 2003). Manual workers may be expected to experience a greater permanent loss of income both because their productivity is more closely tied to their health capital and because a lack of education makes re-training for less physical jobs more challenging. We examine heterogeneity in the effects by age and income, in addition to sex. In countries like the Netherlands, with relatively generous disability insurance (DI) that imposes little sanction to exit once entitlement has been awarded, the incentives to re-train are not strong. Our data allow us to identify individuals entering DI following a health shock and to estimate the magnitude and persistence of their income loss. The DI replacement rate is based upon income prior to a health shock, yet here we estimate an upper bound on the financial incentive to leave DI by comparing this with the income loss experienced by those who remain in work following a health shock. It is an upper bound since those entering DI are presumably in worse health and have lower earnings capacity than those remaining in work. Since our data are also linked to the mortality register, we are able to confirm the extent to which those entering DI do experience greater health deterioration by comparing mortality rates.

Moving beyond the impact of ill-health on the disabled person’s employment and income, identification of the full economic consequences requires recognition of the role of the family, most notably the spouse, in replacing losses of both market and household production. These two roles, which may be characterized as earnings replacement and caring respectively, have contradictory consequences for the spouse’s market labor supply. The income effect of lost earnings that will increase the spouse’s market work and could generate an added worker effect is expected to be relatively more important for female spouses given that male earnings are, on average, greater. On the other hand, women tend to carry the greater share of housekeeping responsibilities and their disability may lead to men increasing time devoted to household production at the expense of market work time. Our estimates are consistent with such gender asymmetry in the labor supply response of spouses to their partners’ disability.

Studies of the 50+ population that rely on self-reported indicators of health generally find a strong negative impact of ill-health, or disability, on earnings and income that operates through employment and work hours rather than wages (McClellan 1998; Bound et al. 1999; Smith 1999; Riphahn 1999; Charles 2003; Wu 2003; Disney, Emmerson, and Wakefield 2006; Lindeboom and Kerkhofs 2009). Our contribution to this evidence base is both through the use of a robust estimator identified from acute hospital admissions providing variation in health that is more likely to be exogenous than self-reported measures and by tracing the employment and income effects over an extended follow-up period using tax records. A few studies follow the same general strategy of identifying from sudden health events. Møller Dano (2005) uses road accidents recorded for a ten percent sample of the Danish population and finds negative effects on disposable income only for older individuals and for those with lower initial incomes. There is a significant effect on employment only for males, for whom the employment rate decreases by around ten percent after an accident and does not recover in the following six years. Halla and Zweimüller (2011) restrict attention to accidents experienced on the way to and from work, which they argue are less likely to induce selection problems although it seems possible that the likelihood of such an accident is related to the nature of the work undertaken. They find negative effects on employment (4 percentage points on average) and on earnings conditional on remaining in employment that are larger for individuals that are less attached to the labor market, such as females and blue-collar workers.

Acute hospitalizations, defined as unscheduled admissions that cannot be postponed since immediate treatment is deemed necessary, cover a far wider range of conditions than those caused by road or commuting accidents. Only eight percent of the admissions we use are due to external causes of injury, which includes road accidents. One-quarter are for diseases of the circulatory system, which includes admissions prompted by heart attack and stroke. Almost one-fifth are related to the digestive system, while another fifth result from injury or poisoning. An acute admission increases the probability of death in the year of admission by three percentage points and by seven points six years after the admission. Exploitation of health variation deriving from such serious conditions increases the external validity of our estimates. Of course, in casting the net wider there is a greater risk that the health events are endogenous to past labor market and health outcomes. But the matching and DiD regression purge bias that would arise through selection on observables and time invariant unobservables respectively. We examine pre-treatment trends in outcomes and find no reason to doubt the DiD assumption of common trends across treatment and control groups in the absence of treatment. We also link the administrative data to survey data for a sub-sample in order to match on more health indicators prior to acute admission. The estimates are robust to this refinement.

There are conflicting findings from the limited literature that examines spousal responses to health shocks. Using US data, Coile (2004) finds a modest increase in labor force participation of the husband when the wife falls ill, but no significant impact on the wife’s labor supply when the husband falls ill (see also Jiménez Martin, Labeaga, and Martínez Granado 1999). Berger (1983), Berger and Fleisher (1984), Charles (1999) and Van Houtven and Coe (2010) all find the opposite, again with US data; wives increase their labor force participation, while men, if anything, reduce theirs. Blau and Riphahn (1999) and Siegel (2006) find that the estimated spousal response is heavily dependent on the health measure used, as well as the earnings level and baseline labor supply of the spouse. We add to this literature by estimating the spousal response to acute hospital admissions using matching combined with difference-in-differences to control for both observable and unobservable confounders.

The results show that ill-health has a substantial causal effect on both employment and income, with the latter effect mainly operating through the former. An acute hospital admission, on average, lowers the probability of remaining in work by seven percentage points (8 percent) and results in a loss of about €1,000 (5 percent) in annual personal income two years after the shock. Four years later, there is no recovery in either employment or income. Individuals remaining in employment two years after the health shock experience an income loss of more than €700 (3 percent). The average loss falls to less than €600 for those in employment after six years indicating only a slight recovery of earnings capacity. Individuals that move from employment onto disability insurance lose ten times as much income -€7,000 (33 percent). These averages mask considerable heterogeneity in the consequences of a health shock. The poor are more likely to move onto DI and experience a greater relative loss of income. They are also more likely to be hit by a health shock. The loss of household income is around 50 percent greater than the disabled individual’s fall in personal income, suggesting substantial negative spillover effects on the earnings of other household members. On average, the probability that the spouse is working is reduced by around one percentage point and spousal income falls by 2.5 percent two years after the hospital admission. But, as predicted, there is gender asymmetry in these effects. Wives are more likely to remain – or even start – working in case their husbands fall ill, while husbands are more likely to withdraw from the labor force when their wives fall ill. The latter effect is most common at the top quartile of the income distribution, which suggests that it is a retirement decision taken by those who can afford to increase leisure time with a spouse who perhaps has a lower life expectancy as a result of the health shock.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section we summarize the main elements of the Dutch sickness and disability insurance arrangements. The data are described in Section 3. Our identification strategy and estimator are set out in Section 4. Section 5 presents the results, Section 6 reports some robustness checks after which a discussion follows in Section 7.

II. Institutional Context - Dutch Sickness, Disability, and Health Insurance

The Netherlands provides an interesting context in which to examine the employment and income effects of disability. One study finds it to be among the European countries in which the effect of ill-health on employment is largest (García-Gómez 2011). This has been attributed to the generosity of its Disability Insurance system (Aarts, Burkhauser, and De Jong 1996; Bound and Burkhauser 1999), which has become more stringent in recent years with a shift in focus from income toward employment protection (De Jong 2008; OECD 2009).

As in most other developed countries, there are three major cash transfer programs for individuals of working age that do not work – Disability Insurance (DI), Unemployment Insurance (UI), and social assistance (welfare). Individuals are entitled to (partial) DI benefits if they have a degree of disability, based on reduced earning capacity, of at least 15 percent1. The dependence on reduced earnings capacity means that an initially high earning individual whose earnings capacity falls substantially as a result of disability would be entitled to DI, whereas an initially lower earning individual left with the same post-disability earnings capacity would not. Entitlement does not depend on whether illness or injury is contracted through work and, more peculiarly, is independent of contributions history. DI benefits are paid after a waiting-period of one year2. Until then, the employer is responsible for financing sick pay, which is equal to 70 percent of the gross wage. However, collective bargaining agreements usually ensure that sick employees receive up to 100 percent of their net salary (Burkhauser, Daly, and De Jong 2008). The replacement rates are defined in terms of previous net salary excluding overtime or bonuses, so actual replacement rates on disposable income might be below 100 percent.

DI pays benefits in two phases. In the first, which lasts up to six years depending on age at onset of disability3, the recipient receives a percentage of previous wage. The percentage is based on the severity of the illness or injury up to a maximum of 75 percent if the individual is assessed as 80 percent disabled or more. The partially disabled, who represent around 20 percent of recipients (OECD 2009), receive pro rata benefits and are allowed to work to close the earnings gap. Two thirds of those awarded partial benefits work, and for them the benefit acts as a wage subsidy (García-Gómez, Von Gaudecker, and Lindeboom 2011). After this first phase, the benefit is no longer set only in relation to previous wage and the severity of disability but is equal to the minimum wage plus an addition increasing in age and previous wage. In all cases this follow-up benefit is constrained to be lower than that paid in the first phase, but it can be paid until the individual reaches the age of 65. Individuals can choose whether to insure against the difference between initial and follow-up benefits, and in most cases this is part of the collective bargaining agreement (De Jong 2008), which implies that in those cases there is no difference between the first and second phase.

Individuals who are not awarded partial disability status, but who become unemployed are entitled to UI. During our observation period, the UI replacement rate was 70 percent and the benefit period ranged from a minimum of six months to a maximum period of 5 years depending on employment history and age. Individuals awarded partial disability status who cannot find gainful employment are entitled to a partial UI benefit of up to 70 percent of lost earnings (De Jong 2008). If the individual cannot qualify for either DI or UI, then s/he can resort to social assistance, which pays lower benefits unrelated to previous earnings.

Health insurance coverage in the Netherlands during the period of analysis was universal, comprehensive and created virtually no labor market incentives. Public sickness funds provided comprehensive and standard coverage, with no deductible or coinsurance, to everyone below an earnings threshold. They charged an income-related contribution that did not vary across occupations. High earners (31 percent) had to insure privately at a risk-related, regulated premium, with less than one percent uninsured (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport 2002). The earnings threshold did not necessarily provide those incurring a health shock with an incentive to reduce their earnings in order to qualify for public insurance since the advantageous risk pool of private insurers (although explicit risk selection was disallowed) meant that premiums were not necessarily greater – often even lower - than income-related contributions to the public schemes. Services covered by private and public insurance were very similar. Unlike disability insurance, health insurance has never been perceived as a source of labor market distortions in the Netherlands.

III. Data

Our data are linked to administrative records from Statistics Netherlands. We use the tax records (RIO), the hospital discharge register (LMR), the Cause-of-Death register (DO), and the Municipality Register (GBA) for the years 1998–2005 inclusive. The hospital register is used to identify our treatment variable - unscheduled hospitalizations that cannot be postponed since immediate treatment is necessary. The tax records provide the outcome measures – employment, DI/UI/pension receipt and disposable incomes. Demographics (age, sex, marital status, household size, and nationality) and location (province and city size) used in the matching are obtained from the municipality register. The death register is used to identify drop out due to death in the follow-up period, which is used as an indicator of the severity of the shock.

The RIO is a longitudinal administrative tax-register covering one third of the Dutch population, representing around five million observations per year from 1998 to 2005. It provides personal disposable income, which is gross income from wage, profit and wealth earnings plus transfers less taxes and premiums. Income by source is not available but the main source of income is identified and this is used to identify labor market status. Specifically, the main source can be income from work, DI, UI, old-age pensions, other social transfers or no income (includes individuals with solely income from capital, and those with only bounded transfers such as allowances for renting and children). As mentioned in the previous sub-section, during the one-year waiting period for DI sickness benefits are paid by the employer. In the tax files, this will appear as income from an employer and individuals receiving sickness benefits will therefore be classified as employed. This is an unavoidable limitation of using the tax files, which impedes our ability to identify the impact of a health shock on employment in the first year after hospitalization. The tax file also provides total household disposable income, which is the sum of the personal incomes of all household members.

The hospital discharge register contains data on both inpatient and day care patients of all general and university hospitals and most of the specialized hospitals in the Netherlands from 1998 to 2005. Each year there are around two million hospitalizations of around 1.6 million distinct individuals. For the entire Dutch population we observe (i) whether the individual entered the hospital, (ii) whether it was an acute admission, (iii) the admission and discharge date, and (iv) the main diagnosis. We identify a health shock as an unplanned hospitalization in urgent need of treatment involving a stay of at least three nights. The unplanned and urgent nature of these admissions makes it more likely that they are exogenous to labor outcomes and is crucial to our identification strategy. However, since urgent and unplanned hospitalizations are not necessarily severe – they could include strapping of a sprained ankle - we impose a minimum length of stay. Further, we impose sample selection criteria in relation to age, initial employment status and previous hospitalizations (see next section). The result is a sample of 17,491 acute hospitalizations with a stay of at least three nights, which constitute our treatment cases.

In Table 1 we show the breakdown of these severe acute admissions by diagnoses on basis of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9. Circulatory diseases are the largest single cause of acute hospital admission, accounting for one-quarter of all cases, and are predominantly cases of the “intermediate coronary syndrome”, acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), and angina pectoris. Injuries and diseases of the digestive system (acute appendicitis, stomach ache) come next, each accounting for one-fifth of acute admissions. Diseases of the musculoskeletal system (a.o. hernia), the respiratory system (COPD, pneumonia) and all kinds of neoplasm each contribute six to eight percent of cases. These three disease categories are known to be important causes of long term disability. Incidence of the remaining physical diseases and conditions is lower. Mental disorders account for less than 2 percent of acute admissions and so our estimates are of the employment effects of mainly physical health impairments.

Table 1.

Treatment Cases by Diagnoses. Acute Hospital Admissions of at Least Three Nights

| ICD 9-CM diagnostic category | Fraction | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 0.251 | 0.297 | 0.160 |

| Injury and poisoning | 0.194 | 0.209 | 0.084 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 0.181 | 0.166 | 0.210 |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 0.129 | 0.123 | 0.141 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 0.080 | 0.078 | 0.083 |

| External causes of injury (V-code) | 0.079 | 0.077 | 0.164 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | 0.073 | 0.072 | 0.075 |

| Neoplasms | 0.065 | 0.056 | 0.082 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 0.050 | 0.032 | 0.084 |

| Mental disorders | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.048 |

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.033 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.026 |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.020 |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.014 |

| Diseases of the sense organs | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.014 |

| Congenital anomalies | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Total number of admissions | 17,491 | 11,630 | 5,861 |

Notes: Rates calculated from treatment cases used in estimation and so are restricted to unplanned, urgent admissions of at least 3 nights included in the RIO tax files, aged 18–64, working, and not having been hospitalized in the previous year.

In Figure 1 we show the impact of an acute admission on subsequent hospitalization and mortality.4 An acute admission of at least three nights is associated with an increase of 17 points in the probability of experiencing another admission in the following year. In subsequent years, the probability remains elevated by at least six points. In the year of the initial admission, the probability of death is raised by three percentage points. It continues to rise steadily in subsequent years reaching an inflated risk of seven percentage points after six years. These descriptives confirm that our treatment variable corresponds, on average, to a physical health shock with a potentially severe and lasting impact on health.

Figure 1.

Average treatment effects of acute admission on probability of future hospitalization and death. Effects estimated by matching treatment cases (acute admission of 3 nights) with controls as described in Section 4. Dashed lines indicate 95 percent confidence intervals.

IV. Empirical Strategy

We compare the labor market status and incomes of individuals who have experienced an acute hospitalization with those who have not. Identification from health variation provided by hospitalizations avoids the justification bias that is suspected when variation in self-reported health is relied on (Bound 1991). We restrict attention to unscheduled and urgent hospitalizations in order to increase the likelihood that the health changes are exogenous and unanticipated. A scheduled, non-urgent hospitalization is more likely to result from a long term deterioration in health arising from lifestyle choices that are correlated, through time preferences for example, with determinants of the lifetime earnings profile. This would bias the estimated impact of health on income. While we cannot completely rule out such bias even when using unscheduled and urgent hospitalizations, we find no difference in the ‘pre-treatment’ income trends of hospitalized individuals and their matched controls. We estimate effects using difference-in-difference regressions with weights obtained from propensity score matching (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983; Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd 1997; Ho et al. 2007; Imbens and Wooldridge 2009).

Treatment and control cases are restricted to individuals who in 1998 were: i) aged 18–64, ii) working – excluding those that are on disability benefits in the year of admission, since these individuals must have been on sickness benefits in the year before admission, and hence do not meet the sample selection criterion of being at work at baseline and, iii) not admitted to hospital. Individuals who experienced an acute hospitalization of at least three nights in 1999 – excluding those related to pregnancy and child birth – form the treatment group. Individuals with other types of hospitalization in 1999 are dropped and so are not included in the control group. Both treatment and control groups are followed for up to six years after the hospitalization of the treatment group, that is until 2005. Note that individuals in the treatment and control group are allowed to have multiple acute hospitalizations over the follow-up period.

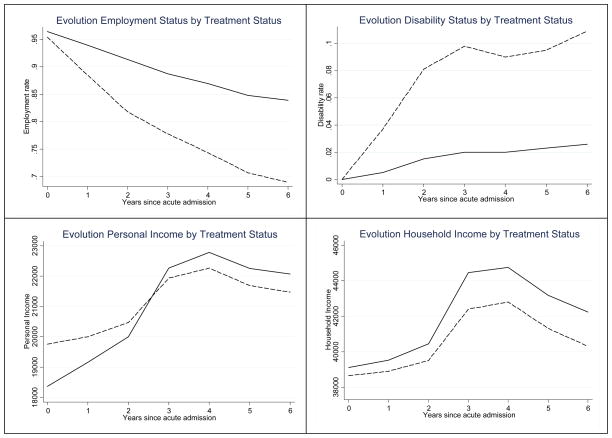

After the baseline year in which all are employed, the employment rate of both the treatment and control groups falls steadily, but the decline is much steeper for the former (Figure 2). Six years after an acute admission less than 70 percent of the treated are employed compared with 84 percent of the control group. Many of the individuals that have an acute admission and subsequently leave employment appear to enter DI. More than ten percent are on DI after six years compared with less than 3 percent of the control group. In the year of the hospital admission the average personal income of the treated individuals is €1400 greater than that of the control group. Thereafter, incomes rise for both groups but the increase is much steeper for the control group with the result that its average income exceeds that of the treatment group by €600 after six years. The initial gap in household income between treatment and control group is relatively small, yet tends to increase over time. These raw differentials suggest that an acute hospital admission does indeed have a substantial negative impact on employment and on income. We now explain how we estimate these effects.

Figure 2.

Employment, DI rates, and average incomes in post-treatment period by treatment status. Treatment is an acute hospital admission of at least three nights. All the individuals are employed in t=−1. Solid lines represent the control group, while the dashed line represents the treatment group.

The propensity score for hospitalization is estimated by a probit including: (1) demographics – age, gender, marital status, province, city size, nationality, and household size; (2) socioeconomic indicators – equivalent household income, and ratio of personal to household income; and, (3) job characteristics – whether the individual is the main breadwinner, and occupation. The probit estimates indicate that older, male, divorced, and low-income individuals are significantly more likely to have an acute hospitalization (Appendix, Table A.1). Using the propensity score we employ a kernel matching approach (Epanechnikov kernel with bandwidth of 0.001) to create comparable treatment and control groups (Becker and Ichino 2002). Additionally, we restrict the sample to observations within the common support range, which results in only very slight reductions in the sizes of the treatment and control groups (from 17,818 to 17,491 and 2,094,101 to 2,053,059 respectively).

Before matching, substantial and statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups in the means of the variables included in the propensity score exist (Table A.1). Matching on the aforementioned indicators ensures a considerable bias reduction close to 100 percent for all variables (Ho et al. 2007). While recognizing the argument that standard t-tests are heavily dependent on the sample size (Ho et al. 2007; Imbens and Wooldridge 2009), it is reassuring that after matching none of the differences in average characteristics are statistically significant at any conventional level despite the huge sample size (Table A.1).

Using propensity score matching, the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) is identified under the assumption that the observable controls and the pre-treatment outcomes include all factors that determine both whether an individual experiences an acute hospitalization and his potential outcome in the absence of this event. Here, we use propensity score matching as a way of “pruning” the data to obtain a comparable set of treated and control individuals. After this initial pre-processing step we run a weighted regression which renders the estimates consistent in case either the matching or the regression step, but not necessarily both, is correctly specified - the “double robustness” property (Ho et al. 2007; Imbens and Wooldridge 2009). However, consistency still relies on the Conditional Independence Assumption. To make this more plausible, we exploit the longitudinal nature of our data and use difference-in-differences to control for fixed unobservable determinants (Heckman et al 1997). We do so by restricting the sample of controls to individuals identical to the treated in terms of pre-treatment discrete outcomes or, in the case of the non-discrete income outcomes, by combining propensity score weighting with regression differences-in-differences5,6. In the latter case, the regression model is:

| (1) |

where the subscript i refers to the individual, and t to the year. Y is the outcome, τ is a year-specific intercept, D is the treatment indicator (D=1 for an acute admission, and D =0 for the control group), and ε is an error term.7 The ATT, captured by δt, is allowed to vary by year. Essentially, by running this weighted DiD regression we weaken the identifying assumption of the matching estimator to the requirement that, conditional on observables, in the absence of hospitalization the evolution (not level) of outcomes from the pre-treatment to post-treatment period would have been the same for the group that was hospitalized and their matched controls who were not (Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd 1997; Blundell and Costa-Dias 2009).

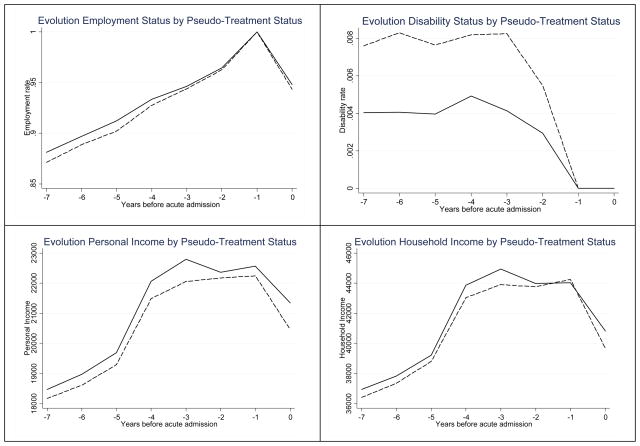

To gauge the plausibility of this parallel-trends assumption, we redefine a pseudo-treatment and control group using the same selection criteria on employment, age and hospitalizations toward the end of our observational period in 2004. We define pseudo-treatment as an acute hospitalization of at least three nights in 2005. Figure 3 illustrates how the pre-treatment outcomes of the weighted pseudo-treatment and control groups evolve over the 1998–2004 period. While the levels of the outcomes differ, their trends are extremely similar in the pre-treatment period. This is reassuring for our identification strategy.

Figure 3.

Employment/DI rates and average incomes in pre-treatment period of pseudo treatment (solid lines) and control groups (dashed lines) distinguished by acute admission in 2005. Pseudo-treatment is an acute hospital admission of at least three nights in the year 2005 (year 0). All individuals are employed in year 2004 (−1). Solid lines represent the pseudo-treatment group and dashed lines represent the pseudo-control groups.

The parameter δt corresponds to the treatment effect in absolute terms. Relative effects can be more meaningful for comparison across socio-demographic groups that differ in baseline outcomes. To obtain relative effects, we divide the ATT in year t by the counterfactual outcome obtained using the common trends assumption for the matched controls.

| (2) |

For employment outcomes, initial conditions are the same and so the relative treatment effect is simply the ATT divided by the mean for the control group in the relevant time period.

To estimate heterogeneous effects by gender, age, etc. we estimate the propensity scores and DiD regressions separately by subgroups defined by each characteristic. The null of homogeneity is tested through the significance of an interaction between the health shock and the characteristic in a model estimated on the pooled (across groups) sample.

V. Results

A. What is the Effect of a Health Shock on Employment and Personal Income?

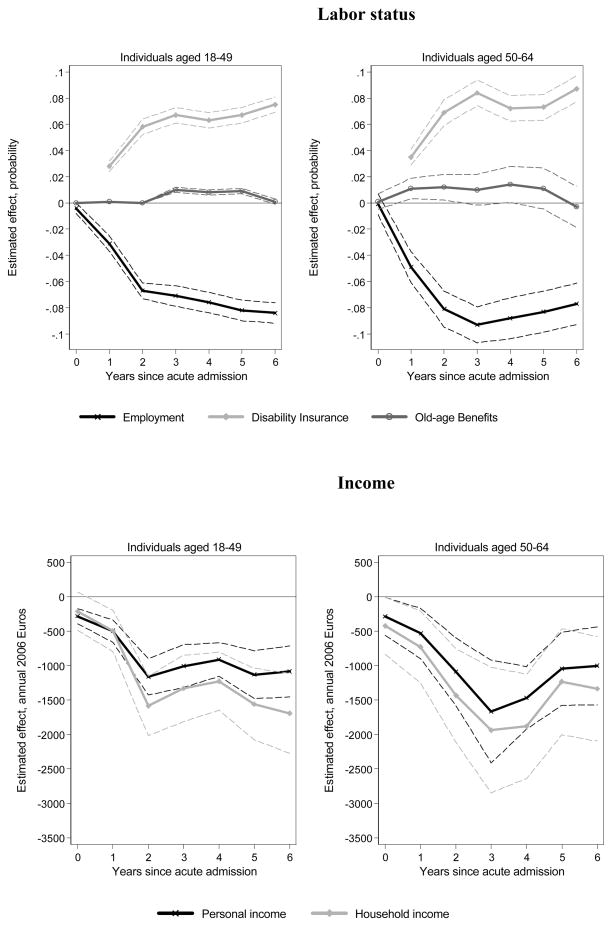

The ATT of acute hospitalization on employment is negative and statistically significant (Figure 4). It is small in the year of hospitalization and the following year, which is to be expected since those on sickness benefits paid by the employer during the first period of work interruption will be recorded in the tax files as receiving their main source of income from employment and so are identified as in work. Two years after hospitalization, the probability of remaining at work is seven percentage points lower for the treatment group (Table 2, row 1), and this difference remains over the remainder of the observation period (Figure 4). The majority of individuals leaving employment enter DI. An acute hospitalization raises the probability of being in receipt of DI by more than two percentage points after one year and by almost eight points after six years. The latter represents a relative increase of over 250 percent. An acute hospitalization appears to raise the probability of retirement only slightly. Two years after the health shock, probability of retirement is raised by a marginally significant 0.3 percentage points. This rises to 0.7 points after four years. The effects on the probabilities of being unemployed, on social welfare and without income are small and insignificant and are not presented.

Figure 4.

Effects of acute hospitalization on employment status and income. ATT of acute hospital admission estimated from propensity score weighted regression DiD regression (equation 1). 95 percent confidence intervals indicated by dashed lines derived from robust standard errors that take account of individual level clustering.

Table 2.

Effects of Acute Hospitalization on Employment and Income Two Years after Hospitalization (t=2)

| Employment | Disability | Retirement | Personal Income | Household Income | Number of observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | Treated | Control | |

| Full sample | −0.071*** (0.003) | −7.9 | 0.062*** (0.002) | 325.5 | 0.003* (0.002) | 6.5 | −1,109.1*** (122.1) | −4.8 | −1,552.0*** (186.2) | −3.5 | 17,491 | 2,053,059 |

| Stay in Work | −730.0*** (154.1)††† | −2.9 | −925.5*** (240.3)††† | −2.0 | 7,299 | 1,149,729 | ||||||

| Transit into DI | −7,001.3*** (353.4) | −32.7 | −8,359.1*** (881.7) | −20.2 | 247 | 1,149,729 | ||||||

| Men | −0.065*** (0.004)†† | −7.2 | 0.056*** (0.003)††† | 349.7 | 0.005** (0.002)†† | 9.1 | −1,210.5*** (165.0) | −4.5 | −1,425.8*** (232.1) | −3.2 | 11,630 | 1,243,744 |

| Women | −0.084*** (0.006) | −9.6 | 0.074*** (0.004) | 294.0 | −0.000 (0.002) | −1.0 | −885.4*** (153.0) | −5.8 | −1,862.8*** (311.2) | −4.2 | 5,861 | 809,315 |

| Aged 18–49 | −0.067*** (0.003) | −7.2 | 0.058*** (0.003)†† | 475.9 | 0.000 (0.000) | 28.4 | −1,162.8*** (134.8) | −5.3 | −1,584.4*** (220.0) | −3.6 | 11,767 | 1,692,611 |

| Aged 50–64 | −0.081*** (0.007) | −10.3 | 0.069*** (0.005) | 207.9 | 0.012*** (0.005) | 9.3 | −1,088.4*** (250.4) | −4.3 | −1,432.1*** (345.7) | −3.3 | 5,724 | 360,448 |

| Poorest | −0.093*** (0.007)††† | −10.6 | 0.074*** (0.005)†† | 338.5 | 0.004 (0.003) | 11.4 | −1,198.2*** (256.5) | −6.4 | −1,439.4*** (385.6) | −4.4 | 4,286 | 503,009 |

| Richest | −0.055*** (0.006) | −6.2 | 0.046*** (0.004) | 282.0 | 0.006 (0.004) | 9.8 | −1,260.3*** (341.3) | −4.2 | −2,292.6*** (498.3) | −3.9 | 4,304 | 515,323 |

| Aged 18–49 by household income quartile | ||||||||||||

| Poorest | −0.094*** (0.008)††† | −10.3 | 0.072*** (0.006)††† | 420.5 | 0.000 (0.001) | 9.7 | −1,201.9*** (291.9) | −6.4 | −1,429.5*** (442.3) | −4.3 | 3,072 | 414,872 |

| Richest | −0.047*** (0.006) | −4.9 | 0.039*** (0.005) | 495.0 | −0.001 (0.001) | −54.2 | −1,148.4*** (306.6) | −4.3 | −2,389.8*** (562.9) | −4.1 | 2,685 | 424,920 |

| Aged 50–64 by household income quartile | ||||||||||||

| Poorest | −0.089*** (0.013) | −11.7 | 0.078*** (0.009)†† | 194.6 | 0.016 (0.010) | 11.3 | −823.4** (366.3) | −4.2 | −791.1 (543.1) | −2.5 | 1,638 | 87,557 |

| Richest | −0.087*** (0.014) | −10.8 | 0.061*** (0.009) | 248.8 | 0.025** (0.011) | 20.1 | −1,946.2** (970.9) | −5.4 | −3,166.6*** (1197.9) | −5.0 | 1,235 | 90,836 |

Notes: ATT - estimate of δ2 from equation (1) - two years after treatment of acute hospital admission estimated from propensity score weighted regression. Asterisks indicate the effect is significantly different from zero (* p-value < 0.1, ** p-value < 0.05, *** p-value < 0.01).

indicates the effect is significantly different from the one in the row immediately below at 10 % or less (†† p-value < 0.05, ††† p-value < 0.01). RATT obtained from equation (2), and denoted in percentages. Robust standard errors accounting for individual clustering in parentheses. The effects on other labor states (unemployment, other social transfer, and the category “no income”) are quantitatively very small and non-significant, hence are not included in the table.

On average, annual personal income is reduced by around €250 in the year of hospitalization (Figure 4). The deficit reaches €1,100 two years later - a relative loss of 4.5 percent (Table 2, row 1) – after which it broadly levels out. The failure of both employment and income to recover after a health shock suggests that the deteriorations in health are permanent and there is little adaptation to reduced functioning. These results are quite different from those presented by Charles (2003) for the US. He found that earnings (not income) fall sharply at the onset of (self-reported) disability and subsequently partially recover. He argues that the recovery can be due to investment in human capital that is productive despite the limitations imposed by the health condition. The most likely reason that a recovery in economic activity is not observed in the Netherlands is the generosity of DI, notwithstanding the rationalization of recent years. Once on DI, it is possible to remain there until retirement and high replacement ratios give little reason to retrain for a new occupation. Møller Dano (2005) also finds that employment rates remain low for men six years after a road accident in Denmark, where DI is also generous.

B. Is the Effect on Income Due to Lost Employment, Reduced In-work Earnings or Both?

Income may fall following a health shock because of complete labor market withdrawal or a partial reduction in hours of work, which may or may not be accompanied by a lower wage rate as a result of a job change. Previous evidence indicates effects on all three outcomes, although the impact on employment appears to be strongest (see the review by Currie and Madrian 1999). The predominance of the employment effect may be due to the incentives created by DI, or because labor market institutions constrain the responsiveness of wages to reduced productivity, making it difficult for disabled individuals to maintain, or obtain, employment. But it could also be that the self-reported health measures that previous studies have predominantly relied upon inflate the estimated effect on employment relative to that on work hours and wages. Individuals who have withdrawn from the labor force have an incentive to report ill-health to justify their status and qualify for DI, while this is not true, or less true, for those working part-time or on low wages.

In Figure 5 we present effects of an acute hospitalization on personal income for individuals who remain in employment until the end of the observation period. There is a significant though small loss of around €250 in the year of admission and the following one, which increases to €730 after two years (Table 2, row 2) – a loss of three percent. The drop in earnings increases again in the third year, after which there is some recovery. So, while ill-health does depress incomes through reduced earnings of those remaining in employment, and not only through the loss of employment, the earnings effect is certainly not dramatic.

Figure 5.

Effect of acute hospitalization on personal income for individuals who remain in employment and those that move onto disability insurance. ATT of acute hospital admission estimated from propensity score weighted DiD regression. Lines as in Figure 4.

Figure 5 also shows that, as would be expected, the average income loss of those entering DI two years after hospitalization and remaining there, is much greater than that experienced by those that remain in work. In the year of hospitalization, those that eventually enter DI already lose more than €1,000, on average, and this rises to €7,000 two years later when they are on DI (Table 2, row 3). This corresponds to a 33 percent-35 percent fall in relative terms, which is higher than that implied by the 75 percent replacement rate offered by DI after the first phase for those fully (more than 80 percent) disabled. Smaller losses in the first year after the shock are consistent with higher benefits in the first phase of DI.

C. Do the Effects Differ by Sex and Age?

Women are more likely to leave employment and to enter DI following an acute hospitalization (Figure 6). Two years after admission, the probability of remaining at work is reduced by 8.4 percentage points for women compared with 6.5 for men (Table 2, rows 4 and 5), a difference which is statistically significant. There is also a statistically significant two percentage point difference in the probability of entering DI, although the relative effect is larger for men (350 percent vs. 294 percent). These discrepancies can arise from gender differences in the nature of the health shocks. We investigate whether this is the sole explanation for gender differences by estimating effects for each type of shock and allowing these to differ by gender. For both sexes, the largest effects on employment are for circulatory diseases, cancers and mental health problems.8 While women are more likely to experience a cancer, they are less likely to suffer from a circulatory disease (see Table 1), suggesting that the distribution of conditions is not the only reason the average effect on employment is larger for females than males. For neoplasms and diseases of the genitourinary system, the magnitudes of the effects are larger for males than for females. For diseases of the musculoskeletal system, injury and poisoning and diseases of the nervous system, there are gender differences in the opposite direction, although this could also reflect different events between men and women being recorded under the same disease group label. Still, it seems that the average effect on employment differs by gender both because the nature of the health shocks experienced differ and because any given shock has a different effect.

Figure 6.

Effects of an acute hospitalization on employment status and incomes by gender. Lines as in Figure 4.

Since males still account for a greater share of household earnings, the income effect of a health induced fall in wages is expected to be larger for males than females and this may contribute to the more muted impact on employment. Despite the greater propensity to leave employment, the absolute drop in personal disposable income is smaller for females than for males – less than €900 versus more than €1,200 after two years (Table 2, rows 4 and 5) – but, as the comparable relative effects indicate, this partly reflects the lower baseline incomes of females (€12,420 vs. €21,996 among those working in our sample), and the estimates are not significantly different from each other.

Older persons have accumulated more human capital that can be destroyed by disability and their shorter residual lifespan gives them less incentive to invest in the acquisition of disability specific human capital. For these reasons, Charles (2003) conjectures that the impact of a health shock on earnings will be increasing with age and any subsequent recovery in earnings will be weaker for older individuals. He finds support for both hypotheses in US panel data. We find that older individuals are less likely to remain at work following acute hospitalization – the employment probability is reduced by 8.1 points for those aged 50–64 compared with a reduction of 6.7 for those aged 18–49 (Table 2) after two years, but these effects are not statistically significant. Also, there is no sign that younger individuals are better able to adapt to their disability and so recover employment (Figure 7). Older individuals are slightly more likely to move onto DI and, not surprisingly, are more likely to retire9. As the baseline probability to retire and move onto DI is higher for older individuals, we find that the relative effect of going into DI of young individuals is twice the relative effect for the older group. Similarly, the relative effect of retiring is three times larger for young individuals compared to the older group.

Figure 7.

Effects of acute hospitalization on employment status and incomes by age. Lines as in Figure 4.

The slightly greater impact of hospitalization on employment at older ages could be attributable to greater destruction of human capital arising from a given health condition but it is certainly also due to greater severity of the health shocks experienced. Older individuals are much more likely to be diagnosed with cancer (10.5 percent versus 4.5 percent) and circulatory diseases (41 percent versus 17 percent). An acute admission increases their probability of dying within six years by 13 points, compared with an increase of 4.2 points for younger counterparts. After three years, losses in personal income are slightly greater for older than younger individuals (although not statistically significant – Figure 7 and Table 2, rows 6 and 7) but the subsequent recovery observable only for the former is not consistent with Charles’ (2003) conjecture that the elderly are less likely to adapt.

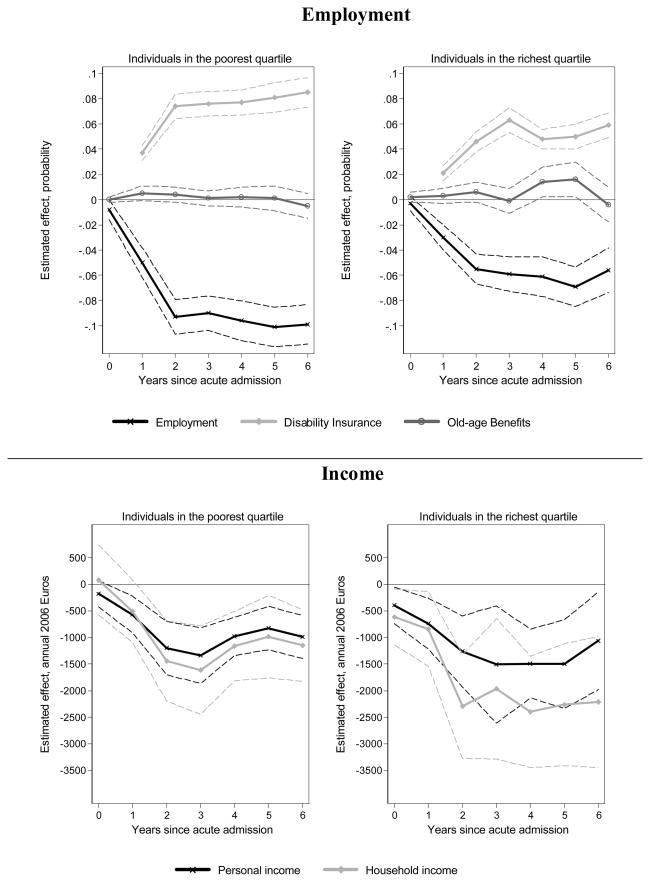

D. Are the Poor Less Protected?

From the propensity score estimates it became clear that those in the bottom quartiles of household income are more likely to end up with an acute hospitalization (see Table A.1). Although clearly these estimates do not represent causal effects, it is a first indication that income inequality may be partly driven by the distribution of health. Here, we seek to explore whether the poor – on top of a larger probability to experience a health shock – are also more vulnerable to the employment and income losses arising from such shocks. We examine such heterogeneity by splitting the sample by quartiles of household income. The probability of remaining at work two years after a health shock is reduced by 9.3 percentage points for those in the poorest quartile compared with a fall of only 5.5 for those in the richest quartile (Figure 8 and Table 2, rows 8 and 9). Apart from the statistically different effect on employment depending on household income, the route of leaving employment also differs by income. The poorest almost exclusively enter DI, while the richest also exit into retirement. The absolute drop in personal disposable income is similar across the two income groups (around €1,200), and hence the relative loss is much larger for the poorest. Given the larger propensity to incur a health shock and larger relative employment and income losses deriving from the shocks, the results are at least suggestive of ill-health contributing to increased income inequality and the socioeconomic gradient in health deriving from a bidirectional relationship between income and health.

Figure 8.

Effects of acute hospitalization on employment status and incomes by initial household income. Lines as in Figure 4. Results shown are not age-adjusted, so may reflect both income-related effects as well as age effects, as older individuals have on average higher income. The last rows of Table 2 show the effects when the population is split by income and age.

The differential effects by income do not seem to be driven by the severity of the shocks - diagnoses and mortality rates differ little by income (not presented). From age 50 and above, the employment effects do not differ much by income (Table 2, rows 10–13). It is primarily in the younger age group that the poorest are more likely to leave employment. But while the probability of leaving employment is independent of income at older ages, the route of exit differs greatly. The older poor are more likely to move onto DI, while the richest older individuals are more likely to enter retirement. Banks (2006) has noted the striking differences in labor force exit routes in the UK with older poor individuals more likely to enter DI while the older rich enter retirement. Here we find that these differential patterns also hold for the response to a health shock. It is not simply that the poor get sick while the rich opt to retire but that the rich are more likely to retire when they get sick. Presumably this reflects differences in pension entitlements by income and therefore in financial incentives for claiming DI.

E. Are there Spillover Effects on the Incomes of Other Household Members?

The extent to which a decrease in personal income translates into a decrease of household income depends on how other household members adjust their labor supply. In the year of hospital admission, the effect on household income differs little from that on personal income (Figure 4). But two years after admission, household income falls, on average, by around €550, or 50 percent more than personal income and thereafter the difference remains roughly constant (Table 2 & Figure 4). This indicates substantial negative spillover effects on the incomes of other household members.

Household income falls by little more than personal income for those that remain in employment (Figure 5), while in addition to the €7,000 fall in personal income after two years for those entering DI, there is an average additional loss around €1,360 in other household income (Table 2, row 3). Given that those on DI are presumably the individuals whose health has deteriorated most and require most care, this suggests that caring needs are a partial explanation for the spillover effects. However, the gender pattern of these effects is not consistent with what one would expect if they are explained by caring roles. When a male is hospitalized, household income actually falls by slightly less than personal income in the year of admission, indicating that there may be even some substitution for lost earnings, while after two years the drop in household income is only €200 larger than that in personal income (Figure 6 & Table 2, row 4). When it is a female that falls ill, the discrepancy between the loss of personal and household income is far larger; the income of other household members falls by as much as that of the woman hospitalized. This suggests substantial asymmetries by gender in the impact of ill-health on the healthy partner’s employment/earnings.

The impact on other household income differs little by age but more markedly by initial household income. In the poorest quartile, there is a small negative spillover effect only two years after hospitalization (Figure 8 and Table 2, row 8). In the richest quartile, the drop in household income (€2,293) after two years equals almost twice the drop in personal income (€1,260) (Table 2, row 9). Like the difference by gender, this is possibly explained by higher initial employment rates and earnings of non-disabled persons in households at the top of the income distribution.

F. What is the Effect on Spousal Employment and Income?

Through an income effect, the lost earnings of the disabled person provide an incentive for his or her spouse to increase labor supply, which is the mechanism underpinning the added worker effect studied in relation to unemployment (Mincer 1962). But ill-health not only reduces labor market productivity, it can also impede functioning in the home. Disability can entail reduced capacity for dressing, washing, cooking and cleaning. Presuming utility derives from the product of these household activities, in addition to market consumption and leisure, labor supply consequences will depend on the impact on market relative to household productivity.10 While the disabled person’s earnings loss provides an incentive for the spouse to raise labor supply, this will be opposed by caring needs and residual household tasks arising from the disabled person’s lost capacity in household activities. Which effect dominates will depend on specialization within the household. If the disabled person was previously the major breadwinner with little housekeeping responsibilities, then the earnings, or added worker, effect is more likely to dominate. On the other hand, if the person struck by ill-health was working only part-time or not at all, but taking on most of the housekeeping responsibilities, then the earnings effects will be modest, or absent, and the household production substitution effect larger. Given typical roles adopted in Dutch households, it seems more likely that female spouses will go out to work to replace lost earnings when their husbands fall ill, while male spouses are more likely to cut back on paid employment to replace lost household production. These predictions are contingent on the gender gap in household productivity not being too large. If, say, the husband is completely hopeless around the house then his capacity to replace the housekeeping duties of his wife when she gets sick will be limited, as will be the opportunity for the wife to find time to replace earnings when the husband gets sick. Should there be any difference between the sexes in preferences for assuming a caring role, then this will also influence the degree to which the effect on spousal employment varies by gender.

To examine whether there is any empirical support for this hypothesis, we restrict the sample to individuals with a partner and estimate the effect of an acute admission on spousal employment and income11. On average, the probability that the spouse is employed is reduced by almost one percentage point two years after hospitalization (Table 3, row 1) and this effect remains after six years (not shown). While this might seem a small effect, it should be considered in relation to the seven point reduction in the employment probability of the partner actually experiencing the health shock. On average, the spouse’s annual income is decreased by €385 after two years - a two percent relative drop – and remains lower by a similar magnitude after six years. While there is some indication (not significant) that retirement increases, employment of spouses is lower mainly because they are more likely to enter DI, the probability of which is increased by half a percentage point after their partners are hospitalized. The predominance of this exit route suggests that correlated health shocks between partners – for example due to assortative mating – rather than a causal effect of one partner’s health on the labor force participation of the other could be responsible for the results. However, this interpretation is not supported by the fact that we found an insignificant and extremely small effect of an acute hospitalization on the probability that the partner is also subsequently admitted to hospital (results available upon request).

Table 3.

Effects of Acute Hospitalization on Spousal Employment and Income Two Years after Hospitalization

| Spousal Employment | Spousal Disability | Spousal Retirement | Spousal Income | Number of Observations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | ATT | RATT | Treatment | Control | |

| Full sample | −0.009*** (0.004) | −1.4 | 0.005*** (0.002) | 9.0 | 0.002 (0.002) | 3.7 | −384.6*** (103.2) | −2.5 | 13,217 | 1,417,877 |

| Female spouse | −0.006 (0.005)† | −1.0 | 0.005*** (0.002) | 9.0 | −0.001 (0.002)†† | −3.1 | −199.3** (88.2)†† | −2.0 | 8,884 | 860,495 |

| Male spouse | −0.016*** (0.005) | −1.9 | 0.006* (0.003) | 8.7 | 0.007** (0.003) | 10.5 | −767.6*** (263.2) | −2.8 | 4,333 | 557,382 |

| Spouse initially working | −0.011*** (0.004) | −1.1 | 0.006*** (0.002) | 22.0 | 0.002 (0.002) | 9.1 | −575.4*** (149.1)††† | −2.9 | 8,845 | 1,061,197 |

| Spouse initially not working | 0.002 (0.007) | 0.7 | 0.004 (0.003) | 2.8 | 0.002 (0.003) | 2.1 | 56.7 (82.5) | 1.0 | 4,405 | 359,413 |

| Female spouse, initially working | −0.009* (0.005) | −1.1 | 0.006** (0.003) | 19.1 | −0.001 (0.002) | −6.0 | −326.6*** (139.3)†† | −2.3 | 5,098 | 555,374 |

| Female spouse, initially not working | 0.003 (0.008) | 1.5 | 0.003 (0.003) | 3.5 | −0.000 (0.003) | −0.0 | 55.0 (81.3) | 1.4 | 3,814 | 307,152 |

| Male spouse, initially working | −0.014*** (0.005) | −1.5 | 0.005** (0.003) | 30.3 | 0.005* (0.003) | 19.6 | −953.9*** (302.6)††† | −3.4 | 3,747 | 505,823 |

| Male spouse, initially not working) | −0.022 (0.018) | −11.9 | 0.008 (0.014) | 1.9 | 0.016 (0.015) | 4.9 | 2.6 (333.7) | 0.0 | 591 | 52,261 |

| Household income quartile | ||||||||||

| Poorest | −0.008 (0.008) | −1.3 | 0.011*** (0.003)†† | 22.0 | −0.001 (0.002)†† | −4.5 | −282.5 (234.3) | −2.7 | 3,237 | 346,721 |

| Richest | −0.019*** (0.007) | −2.6 | 0.001 (0.003) | 2.2 | 0.006 (0.004) | 12.1 | −809.1*** (230.0) | −3.7 | 3,309 | 355,908 |

| Female spouse by household income quartile | ||||||||||

| Poorest | −0.004 (0.011)††† | −0.8 | 0.008** (0.004)†† | 19.8 | −0.002 (0.002)†† | −9.1 | −49.2 (158.7)††† | −0.1 | 2,324 | 235,354 |

| Richest | −0.018** (0.009) | −2.7 | 0.002 (0.004) | 2.9 | 0.003 (0.004) | 6.5 | −649.1*** (243.1) | −4.3 | 2,155 | 200,369 |

| Male spouse by household income quartile | ||||||||||

| Poorest | −0.018 (0.012) | −2.2 | 0.021*** (0.008)† | 24.4 | 0.000 (0.006)††† | 0.8 | −762.2 (665.8) | −3.5 | 913 | 111,367 |

| Richest | −0.021** (0.010) | −2.4 | 0.000 (0.005) | 0.9 | 0.013 (0.008) | 16.6 | −1242.6*** (472.8) | −3.6 | 1,154 | 155,503 |

Gender differences in the impact of a health shock on spousal labor supply are consistent with the hypothesis advanced above. An acute hospitalization has no significant impact on the employment probability of a female spouse but reduces that of a male spouse (Figure 9 and Table 3, rows 2 and 3), a difference that is statistically significant. Two years after the woman enters hospital, on average, her husband is more than 1.5 percentage points less likely to be working and this increases to two points after six years. The probability of entering DI is raised for female but not male spouses. Correlated health shocks do not therefore appear to explain the fall in male spousal employment. This fall is mostly attributable to a rise in the retirement probability - a man is more likely to retire when his wife’s health deteriorates. A woman’s retirement is not affected by a health shock to her husband. Statistically significant gender differences in the impact on spousal income derive from those on employment, although they also reflect initial differences in the levels of income. On average, the annual income of a male spouse falls by €767 two years after his wife is admitted to hospital, while the income of a female spouse falls by €200 (Table 3, rows 4 and 5).

Figure 9.

Effects of an acute hospitalization on probability of employment, disability insurance, old-age benefits (by gender). Lines as in Figure 4.

Disability can reduce spousal employment by increasing the rate of exit from work and/or reducing the rate of re-entry into work. Since these effects can differ, the observed gender differences in the spousal employment effects could reflect differential initial participation rates. Indeed, when we restrict the sample to spouses initially in work, the employment probability falls significantly for female, and not only male, spouses. The effect is larger on the employment of male spouses – a fall of 1.5 percentage points after two years compared with a decline of 1.1 points for female spouses (Table 3, rows 6 and 8). This difference is consistent with the higher average earnings of men within working couples that will result in a larger income effect on the labor supply of female spouses when their husbands reduce work because of disability. Two years after hospitalization, the loss of income experienced by initially working female spouses (€327) is only one-third of that experienced by male spouses (€950) (Table 3, rows 6 and 8), a difference that is statistically significant. Among spouses that were not working when their partners were hospitalized, there is no significant impact on their employment probability (Table 3, rows 7 and 9). The point estimate is positive for female spouses but its small size and significance give no reason to reject the conclusion that there is no added worker effect of disability. For male spouses, the point estimate indicates a 2.2 percentage point reduction in the probability of entering employment. The insignificant difference from a zero effect may simply be attributable to the relatively small sample of non-employed males living with (initially) employed females.

These findings contradict those of Jiménez Martin, Labeaga, and Martínez Granado (1999) and Coile (2004) but are partially consistent with Charles (1999) and Van Houtven and Coe (2010) who both find that husbands are more likely to stop working in case their wives become disabled. The latter two studies also find that females are more likely to compensate for the earnings loss if their husbands fall ill. We find no significant evidence of such an added worker effect.

The impact on spousal employment varies with income. There is no significant impact on the employment probability of both male and female spouses in the bottom quartile of the household income distribution (Table 3, rows 12 and 14). This is despite a significant increase in the probability of entering DI. This could be due to correlated health shocks in this population – individuals with a low health stock marry others. However, this hypothesis is not supported by the fact that spousal hospital admission rates were not affected by the health shock of the individual. An alternative and perhaps more plausible explanation is that a learning effect is operating, in which spouses find out about the generous access to the Dutch DI system after entry of their sick spouse.

Employment does fall for spouses in the richest quartile of households. Male spouses in this group exit employment mainly via retirement. There is an average drop of €1,242 in the personal income of husbands from the fourth quartile (Table 3, row 15). This is even larger than the income loss experienced by their unhealthy wives (not shown), although in relative terms it is no greater than the income loss of female spouses in the richest quartile.12 Provision of informal care is certainly one potential explanation for the reduced spousal employment, and the consequent fall in income. The fact that it is only evident among richer households – for whom formal care is more affordable – suggests that another important reason may be the desire to enjoy joint leisure time, the marginal utility of which has increased due to downwardly revised expectations of the disabled partner’s lifespan (Maestas 2001; Gustmann and Steinmeier 2004).

VI. Robustness Checks

Our findings are robust to a number of choices made in the analysis. Propensity score matching with a bandwidth of 0.001 achieved satisfactorily balanced treatment and control groups. The baseline estimates are very robust to using a narrower bandwidth of 0.0001 (Table 4). The estimated effects on employment, income and, particularly, retirement increase in magnitude using a broader bandwidth of 0.01. Consistent with this, the effects become still larger in magnitude when the propensity score weights are dropped from the regressions. We interpret this as indicating that not accounting properly for differences in observable characteristics—particularly age—tends to result in overestimation of the effects. It is reassuring that in terms of direction of effects, significance and broad magnitude (with the exception of the effect on retirement) the baseline estimates are consistent with those obtained without application of propensity score weights.

Table 4.

Robustness Checks on Estimated Effects of Acute Hospitalization on Employment and Income Two Years after Hospitalization

| Employment | Disability | Retirement | Personal Income | Household Income | Number of observations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | ||||||

| Baseline specification | −0.071*** (0.003) | 0.062*** (0.002) | 0.003* (0.002) | −1,109.1*** (122.1) | −1,552.0*** (186.2) | 17,491 | 2,053,059 |

| Bandwidth | |||||||

| Narrow (0.0001) | −0.071*** (0.003) | 0.062*** (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | −1,102.6*** (122.5) | −1,546.3*** (187.9) | 17,491 | 2,053,059 |

| Wide (0.01) | −0.085*** (0.003) | 0.064*** (0.002) | 0.017*** (0.002) | −1,364.7*** (128.9) | −1,736.0*** (192.4) | 17,491 | 2,053,059 |

| No propensity score weights | −0.095*** (0.002) | 0.066*** (0.001) | 0.027*** (0.001) | −1,563.7* (938.0) | −1,844.5*** (563.4) | 17,491 | 2,053,059 |

| Length of stay | |||||||

| ≥ 1 night | −0.059*** (0.003) | 0.051*** (0.002) | 0.001 (0.001) | −952.2*** (110.2) | −1,096.0*** (274.7) | 25,089 | 2,053,059 |

| ≥ 4 nights | −0.077*** (0.004) | 0.068*** (0.003) | 0.003* (0.002) | −1,180.6*** (131.4) | −1,589.0*** (198.7) | 15,031 | 2,053,059 |

| Excluding observations dying within follow−up period | −0.070*** (0.003) | 0.058*** (0.002) | 0.006*** (0.002) | −1,140.1*** (125.7) | −1,525.1*** (191.1) | 15,960 | 2,032,117 |

| More extensive set of matching variables from household survey | −0.059** (0.030) | 0.068*** (0.022) | 0.006 (0.017) | −909.5* (528.4) | −2,628.6** (1303.0) | 184 | 20,375 |

Notes: As in Table 2. The final row of estimates is derived from the subsample included in the POLS survey including more extensive set of variables (education, job characteristics, hours worked, home ownership, self-assessed health, hampered in daily activities, GP visits, smoker status and frequency of engagement in sports) used in matching.

The length of hospital stay used to identify a sufficiently serious health shock is essentially arbitrary. We have rerun the analyses using one and four nights rather than the three nights used in the baseline estimates. It is reassuring that the magnitude of all effects increase using longer lengths of stay, which correspond to more severe health shocks (Table 4). The differences in magnitudes are not sufficiently large to markedly change any of our conclusions. Selective mortality could potentially introduce bias since treatment cases experiencing an acute hospitalization are more likely to die within the observation period than control cases. To examine whether this appears to be a problem, we have repeated the analyses using only individuals that remain alive throughout the whole six-year follow-up period. The estimates obtained from this restricted sample are very similar to those generated by the full sample (Table 4).

The effectiveness of our matching is potentially compromised by the omission of characteristics, such as health, job characteristics, lifestyle and education, that could be correlated with both the propensity to be hospitalized and labor market outcomes. We matched a sub-sample of individuals for which we have more extensive information from a household survey (POLS) that samples a representative cross-section of the non-institutionalized Dutch population of around 20,000 respondents in the years 1998–2001, to the hospital discharge and tax files. Using this sub-sample reduces the number of treated cases to only 189, which makes it impossible to perform all subgroup analyses and is the reason it is not used for the baseline estimates. The POLS collects additional information on health (self-assessed health, a binary indicator of whether ill-health hampers daily activities), health behavior (number of general practitioner visits, smoker status and frequency of engagement in sports) and socioeconomic characteristics (education, number of hours worked, job characteristics and home ownership). In the propensity score estimates, only the marginal effect of the “Very Good” category of self-reported health is statistically significant, although all health and behavioral variables combined are jointly significant. Hence, the omission of these variables in the main analyses may introduce some selection bias, although we are not too worried about this since using these additional characteristics in the much smaller sub-sample analysis produces similar (but less precise) estimates to those obtained from the baseline specification and sample (Table 4). This builds confidence in the effectiveness of the matching on the more limited set of observable characteristics in the baseline sample.

VII. Conclusion

We find that a health shock – measured by an acute hospitalization - significantly and permanently reduces the probability of continued employment. For working-age individuals in the Netherlands, the probability of remaining in work two years after hospital admission is reduced by seven percentage points and the effect remains stable up to six years after the health shock. On average, an acute hospitalization reduces annual personal income by just over €1,000 (five percent) two years after admission, and there is only a marginal recovery from this over the next four years. Individuals who remain in employment experience only a 2.9 percent fall in income – indicating some, but not substantial, downward adjustment in work hours and/or wages. Those that transit into disability insurance – the majority of those leaving employment - face an average 33 percent income loss, which is broadly consistent with the replacement rate guaranteed by Dutch DI. Remaining in work after a health shock obviously provides the best protection of income, but this is not an option for all individuals. Those experiencing the most severe health shocks—defined by diagnosis, future hospitalizations and mortality—are least likely to remain in employment and most likely to move onto DI. Consequently, implementation of the recent shift in policy focus from income to job protection is likely to be challenging. It is, nonetheless, warranted.

The magnitude of the effects of health shocks on employment and income are larger than those obtained by Charles (2003) for the US and Halla and Zweimüller (2011) for Austria, which possibly derives from the generosity of the Dutch DI system. Moreover, the failure of employment rates and incomes to recover up to six years following a hospital admission must to some degree be due to the lack of incentives and sanctions that respectively encourage and force DI claimants to re-enter employment in the Netherlands. Measures have been taken in recent years to cure the second Dutch disease not by reducing DI generosity but by increasing the stringency of the qualifying incapacity test, as well as reexamination of disability status after entry (Burkhauser et al 2008; Burkhauser and Daly 2011). Available evidence suggests that this has been successful in reducing the inflow into DI without increasing the inflow into other social security programmes (De Jong, Lindeboom, and Van der Klaauw 2011; Euwals, Van Vuren, and Van Vuuren 2012). However, there has been a smaller impact on the rate of outflow. Our finding that DI dependence continues to rise up to six years after an initial health shock suggests that further measures, consisting of periodical re-assessment of work capacity, re-training and counseling, are necessary to encourage and enable DI claimants to re-integrate into the labor market.

The employment and income losses resulting from a health shock are larger for older (50+) individuals but this seems to be attributable to the greater severity of the health conditions experienced. While younger individuals should have a greater incentive to retrain (Charles 2003), there is no evidence that they are more likely to recover from the employment and income losses imposed by disability. This may be attributable to the dampening effect of the DI system at that time on retraining incentives.

Lower income individuals are more likely to both suffer a health shock and to leave employment – mainly through entering DI - as a result. They also experience a larger relative loss of income. It follows that the unequal distribution of health coupled with the unequal impact of health shocks by income must raise income inequality. In the Netherlands, where disability benefits are strongly related to previous earnings, the income loss arising from ill-health is constrained. In the UK, for example, where disability benefits are paid at a flat rate, the average income loss is expected to be far greater. This policy difference presumably helps explain why the Netherlands has the lowest degree of income-related health inequality in Europe, while the UK has one of the highest (Van Doorslaer and Koolman 2004).

A health shock has important spillover effects on the employment and incomes of non-disabled household members. On average, household income falls by 50 percent more than the income loss experienced by the person admitted to hospital. His or her spouse’s probability of being employed falls by 1.5 percentage points three years after the health shock and does not subsequently recover. Spouses who were initially working have an increased probability of leaving employment. There is no evidence of an added worker effect – spouses do not enter work to replace the lost earnings of their disabled partners. Consistent with the findings of Charles (1999) and Van Houtven and Coe (2010), the impact on employment is greater for a male than a female spouse. This is partly due to the higher initial participation rate of male spouses but among those initially employed, male spouses are still more likely to leave employment following a deterioration in the health of their wives. One explanation for this gender asymmetry is that husbands assume housekeeping responsibilities mainly carried out by women prior to their disability while the greater earnings loss when the man falls ill creates a stronger income effect keeping their wives at work.

A health shock reduces the employment of both male and female spouses in the richest households while there is no significant effect among the poorest households. This is not what we would expect if spouses were withdrawing from employment in order to provide informal care since richer households are better able to afford formal care. An alternative explanation is that only the better off are able to enjoy the higher marginal utility that leisure offers both because the disabled spouse is at home and because his or her life expectancy may have been reduced. Taking early retirement to make the most of your remaining life together with your sick partner is attractive if you can afford it.

Acknowledgments