Background: Serine residues in extensin, a cell wall protein in plants, are glycosylated with O-galactose.

Results: Genes encoding the serine O-α-galactosyltransferase were isolated from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and plants and were characterized.

Conclusion: The serine O-α-galactosyltransferases belong to a novel glycosyltransferase class existing only in the plant kingdom.

Significance: The identification of novel glycosyltransferases contributes to elucidation of how protein glycosylation has evolved in plants.

Keywords: Cell Wall, Galactose, Glycosylation, Glycosyltransferase, Plant

Abstract

In plants, serine residues in extensin, a cell wall protein, are glycosylated with O-linked galactose. However, the enzyme that is involved in the galactosylation of serine had not yet been identified. To identify the peptidyl serine O-α-galactosyltransferase (SGT), we chose Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a model. We established an assay system for SGT activity using C. reinhardtii and Arabidopsis thaliana cell extracts. SGT protein was partially purified from cell extracts of C. reinhardtii and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry to determine its amino acid sequence. The sequence matched the open reading frame XP_001696927 in the C. reinhardtii proteome database, and a corresponding DNA fragment encoding 748 amino acids (BAL63043) was cloned from a C. reinhardtii cDNA library. The 748-amino acid protein (CrSGT1) was produced using a yeast expression system, and the SGT activity was examined. Hydroxylation of proline residues adjacent to a serine in acceptor peptides was required for SGT activity. Genes for proteins containing conserved domains were found in various plant genomes, including A. thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. The AtSGT1 and NtSGT1 proteins also showed SGT activity when expressed in yeast. In addition, knock-out lines of AtSGT1 and knockdown lines of NtSGT1 showed no or reduced SGT activity. The SGT1 sequence, which contains a conserved DXD motif and a C-terminal membrane spanning region, is the first example of a glycosyltransferase with type I membrane protein topology, and it showed no homology with known glycosyltransferases, indicating that SGT1 belongs to a novel glycosyltransferase gene family existing only in the plant kingdom.

Introduction

Serine O-α-galactosylation is a plant-specific post-translational modification of proteins that is found in extensins and arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs),2 which are members of the hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein (HRGP) family. HRGPs consist of a superfamily of plant cell wall proteins that are subdivided into three families, extensins, AGPs, and proline-rich proteins (1–6). The proline residues of HRGPs are hydroxylated by prolyl-4-hydroxylases (P4Hs) to yield hydroxyproline (Hyp) residues in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or cis-Golgi apparatus, and these Hyp residues are then modified by various O-glycosylation steps (7). Hydroxyproline O-galactosyltransferase (HGT), for which the gene was recently identified, transfers O-linked β-galactose to alternating Hyp residues such as Xaa-Hyp-Xaa-Hyp repeats in AGPs (8–11). It was reported that only one galactose (Gal) was added per peptide molecule to the C-terminal or penultimate Hyp residue of the (alanine-Hyp)7 peptide based on an in vitro assay using microsomal membranes of Arabidopsis thaliana (12), and subsequently, a large arabinogalactan structure is assembled (13, 14). In addition, galactosylation of serine residues in AGPs is also reported (15, 16). Large carbohydrate blocks, which are estimated to be arabinogalactan components, are linked to the serine residues in AGPs of Acacia senegal (gum arabic) (17). It was revealed that one member of the AGPs is involved in the differentiation of the tubular element of vascular bundles; thus, AGPs are not simply a structural component of cell walls (18–20).

Extensins have continuous Hyp residues that can be found in the sequence Ser-Hyp-Hyp-Hyp-Hyp, which is called an extensin motif (21). The continuous Hyp residues in this motif are modified with O-arabinofuranose (22), and oligoarabinose is constructed by the addition of several arabinose residues. Recently, three hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferase genes (HPAT1–3: At5g25265, At2g25260, and At5g13500), involved in β-arabinofuranosylation of hydroxyproline, were identified in A. thaliana (23). After the β-arabinofuranosylation of Hyp residues, oligoarabinose structures are constructed. It is reported that RRA1–3 (reduced residual arabinose 1–3: At1g75120, At1g75110, and At1g19360) enzymes transfer β-1,2-linked arabinofuranose to the arabinofuranose residues that are linked to Hyp residues, and the XEG113 (At2g35610) enzyme further transfers β-1,2-linked arabinofuranose (24, 25). Consequently, the oligoarabinose structures consist of 1–4 arabinofuranose residues in plants (22). Extensins are considered to polymerize each other by intermolecular cross-linking via tyrosine residues, to reinforce cell walls by fixing the distance of fine cellulose fibers (26), and to have a role as a negative regulator of cell extension (27), although the function of extensins in the cell wall is not fully understood. It was reported that the addition of the correct oligoarabinose to Hyp residues of extensins is essential for root hair growth by analyses using mutants of rra1–3 and xeg113 arabinosyltransferase genes (24, 25), and loss-of-function mutations in HPAT-encoding genes cause pleiotropic phenotypes (23). The serine residue in the extensin motif is also modified with α-linked galactose (Ser-O-αGal) (28–31). However, there have been no reports on the role of Ser-O-αGal in plants, due to the lack of identification and characterization of peptidyl serine O-α-galactosyltransferase (SGT). Thus, it is essential to identify the responsible genes to understand the role of Ser-O-αGal.

In this report, we chose Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a model organism to identify SGT genes. The unicellular alga C. reinhardtii has a cell wall formed entirely from HRGPs, lacking abundant carbohydrate polymers. HRGPs of C. reinhardtii are similar in several aspects to extensins in higher plants (32). Because culture and homogenization of C. reinhardtii are much easier than other model plant like A. thaliana, we selected the C. reinhardtii cell wall-less mutant (CC-503) for partial purification of SGT. Using this mutant cell, we established an assay system for SGT, partially purified the SGT protein, determined the SGT partial amino acid sequence, and cloned the SGT gene. Based on the amino acid sequence obtained from C. reinhardtii, we further cloned and characterized SGT genes of higher plants such as A. thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. This study revealed that the SGT gene is a member of a novel gene family with no homology to any known glycosyltransferases, yet is widely conserved in the plant kingdom, from green algae such as Chlamydomonas to higher plants such as Arabidopsis and Nicotiana. Sucrose density gradient centrifugation indicated that AtSGT1 is predominantly localized to the ER. In addition, we investigated phenotypes of AtSGT1 mutants and found that SGT has some role in determining the size of plants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Materials

C. reinhardtii CC-125 and cell wall-less mutant CC-503 were purchased from the Chlamydomonas Resource Center (University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN), and grown in 12-liter vessels containing 10 liters of medium (0.2% tryptone, 0.1% Bacto-peptone, 0.2% yeast extract, 0.1% sodium acetate, 0.001% CaCl2) under visible light at 23 °C for 3 days. Seeds of A. thaliana (Col-0, SALK_059879C, and SALK_054682) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Columbus, OH). Because SALK_054682 is a heterozygous mutant, we obtained a homozygous mutant from the T4 generation by genomic PCR. A. thaliana cells from calli derived from sterilized seeds were grown in 0.1 liter of Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 1 mg/liter 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 3% sucrose and shaken at 110 rpm at 23 °C for 1 week. Plants of A. thaliana were grown at 23 °C under long-day conditions consisting of 14.5 h of light on Murashige and Skoog medium or soil. Tobacco BY-2 cells were grown as previously described (7).

Preparation of Microsomal Fractions

Cell extracts of C. reinhardtii CC-503 mutant cells were prepared from cells grown in 10 liters of medium. After cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed in 400 ml of a buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and 0.1% Triton X-100, the cell lysates were centrifuged at 3000 × g, and the supernatants (S10) were ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C to obtain an ER- and Golgi-enriched pellet (P100) and a cytosolic supernatant (S100). P100 was suspended in buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 0.1 m NaCl at 4 °C. After ultracentrifugation of the suspended P100 at 100,000 × g, the resulting supernatant (CrP100) was used as a crude enzyme solution. Calli of A. thaliana and N. tabacum (BY-2) cells were harvested using filter paper and then lysed in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. The lysed cells were suspended in buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2. The suspension was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. The resultant supernatants were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C, and the pellets were suspended and dialyzed in buffer containing 20 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% CHAPS to prepare the microsomal fraction. Protein concentration was measured by the BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Acceptor Peptide

We used AtEXT peptide (FITC-Ahx-VYKSOOOOV-NH2, Mr 1519.1), VYKAOOOOV peptide (FITC-GABA-VYKAOOOOV-NH2, Mr 1504.5), AtEXT-P peptide (FITC-Ahx-VYKSPPPPV-NH2, Mr 1453.7), and AtEXTa peptide (FITC-GABA-KSOOOO-NH2, Mr 1159.1) as acceptors for SGT assay. ϵ-Aminocaproic acid sequences (Ahx) or γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) was used as spacers. O indicates hydroxyproline. These peptides were purchased from Greiner Bio-One (Kremsmuenster, Austria) or AnyGen (Gwang-ju, Korea).

Assay of Peptidyl SGT Activity

Assay mixtures contained the following in a total volume of 6.25 μl: 5 mm UDP-galactose, 25 μm acceptor peptide, 0.1 m MOPS-NaOH buffer, pH 7.0, containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (w/v final concentration), 5 mm MnCl2, 2 mm EDTA, and 2.5 μl of the various enzyme fractions. Mixtures, including enzyme fractions, were incubated at 30 °C for 1–12 h. Reactions were stopped by heating at 95 °C for 5 min.

HPLC Analysis

Enzymatic products were separated by reverse-phase HPLC (Cosmosil column 5C18-AR-II inner diameter, 4.6 × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). They were eluted by a linear gradient of 22–22.5% acetonitrile containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for 30 min (AtEXT peptide), 25–26% for 40 min (AtEXT-P peptide), and 15–22.5% for 30 min (AtEXTa peptide) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and detected by fluorescence at 530 nm (excitation, 488 nm) with a model RF-10A XL fluorescence detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

β-Elimination

β-Elimination was carried out in a solution containing 1% triethylamine, 0.5% NaOH and 20% ethanol by incubation at 50 °C for 5 h (33). Products were purified with a Sep-Pak Light C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) and then analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis

Enzymatic products were collected, lyophilized, and suspended in deionized water. The matrix used for mass spectrometry was α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma), which was dissolved in acetonitrile/water (5:5, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA at 10 mg/ml. Equal volumes (1 μl each) of sample and matrix solution were mixed and dried on the target plate, followed by MALDI-TOF-MS. Mass spectra were obtained using an Ettan MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer (GE Healthcare) in the positive-ion mode.

Galactosidase Treatment

We used β-galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae (Sigma) and α-galactosidase from guar seed (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland). Samples were incubated with 0.25 units of β-galactosidase at 30 °C or 0.1 unit of α-galactosidase at 40 °C for 3 h. Reactions were stopped by heating at 95 °C for 5 min.

Monosaccharide Analysis

O-Glycosylated peptides were incubated in 4 m TFA at 100 °C for 3 h and dried. After N-acetylation, the hydrolysates were labeled with fluorescent 2-aminopyridine using the Palstation pyridylamination reagent kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). The pyridylamino (PA)-labeled monosaccharides were purified (34) and analyzed by HPLC using a TSKgel sugar AXI column (inner diameter, 4.6 × 150 mm, Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min with 0.7 m potassium borate, pH 9.0, containing 10% acetonitrile at 65 °C. The PA-labeled monosaccharides were detected by fluorescence intensity at 380 nm (excitation wavelength 310 nm). PA-glucose, PA-mannose, and PA-galactose were detected at 55, 62, and 97 min, respectively (35).

MS/MS Analysis

Proteins recovered from gel pieces were analyzed using LC-MALDI-MS/MS by Theravalues (Tokyo, Japan).

Cloning and Expression of SGT1 in Yeast Pichia pastoris

CrSGT1-CD+UR and CrSGT1-CD gene fragments were amplified by PCR using the cDNA library (Chlamydomonas Resource Center) as a template and the following primer sets: CrSGT1-CD+UR, 5′-GCTTCAGCGGAGGAGCCGGGCTTCG-3′ and 5′-CTAGGTATTGAGGCGGCCCAACAGCGA-3′, and CrSGT1-CD, 5′-GCTTCAGCGGAGGAGCCGGGCTTCG-3′ and 5′-CTACTCCTTCCACTCCTCGCACTTGGG-3′. AtSGT1-CD1+CD2, AtSGT1-CD1, and AtSGT1-CD2 gene fragments were amplified by PCR using cDNA clone pda06988 (RIKEN BioResource Center, Tsukuba, Japan) as a template and the following primer sets: AtSGT1-CD1+CD2, 5′-CAAATGGCACCGTATCGGATCCAC-3′ and 5′-TCACAACGTGCTGAATCTCCCTTCAGA-3′; AtSGT1-CD1, 5′-CAAATGGCACCGTATCGGATCCAC-3′ and 5′-TCAGAAAGTTTTGCTCTTCAGAAAGCT-3′; and AtSGT1-CD2, 5′-ATGGAGTTAACAAGGCCTAAACTG-3′ and 5′-TCACAACGTGCTGAATCTCCCTTCAGA-3′. NtSGT1-CD2 gene fragment was amplified by PCR using cDNA of N. tabacum as a template and following primer sets: 5′-GCAGAACTAAGTCGGCCAAA-3′ and 5′-TCTCATGGAACTGAATGTCC-3′. The cDNA of N. tabacum was prepared using rapid amplification of cDNA ends (36). Recombinant proteins of SGT1s were expressed using the Pichia expression kit (Invitrogen). To express recombinant SGT1s with His6-3×FLAG tags at the N terminus, each SGT1 gene fragment, amplified by the above PCRs, was inserted into the AvrII site of pPIC9, and His6-3×FLAG tags were inserted into XhoI/EcoRI site of the multiple cloning site of pPIC9. These expression plasmids were introduced into P. pastoris cells using the lithium acetate method (37). The transformants were precultured in 0.2–5 liters of YPAD medium (2% Bacto-peptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, and 40 mg/liter adenine sulfate) at 30 °C for 3 days. Pichia cells were harvested and resuspended in same volume of BMMY medium (2% Bacto-peptone, 1% yeast extract, 1.34% yeast nitrogen base, 0.1 m potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, and 0.5% methanol) containing 2% casamino acids. For induced expression of recombinant SGT1s, Pichia cells were cultured with 0.5% methanol/day at 25 °C for 3 days. CrSGT1-CD+UR, CrSGT1-CD, and NtSGT1-CD2 proteins were partially purified using Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) and anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) from the supernatants of culture. AtSGT1-CD1+CD2, AtSGT1-CD1, and AtSGT1-CD2 proteins were partially purified using Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow and anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel from the cell lysates after the induction of expression, because we could not obtain enough protein for the assay from the culture supernatants.

Immunoblotting and Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting. Anti-FLAG was purchased from Sigma. Anti-AtSGT1 antibody was specific for the C-terminal sequence (RNKRRTSYSNTGFLDTK) of AtSGT1 and was produced by Operon Biotechnology (Tokyo, Japan). Anti-PIP1 (38) and anti-Sec61 (39) antibodies were described previously. Anti-BiP and JIM84 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) or CarboSource Services (Athens, GA). Anti-AtTLG2a (40) was kindly provided by Dr. N. V. Raikhel. Each primary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:1000 to 1:10,000. We then used anti-mouse IgG conjugated with HRP (Sigma) and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with HRP (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) to detect the following: anti-AtSGT1, anti-Sec61, anti-AtTLG2a, and anti-PIP1; anti-rat IgM conjugated with HRP to detect JIM84; or anti-goat IgG conjugated with HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to detect anti-BiP. In each case, secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:5000. An ECL Plus kit (GE Healthcare) was used to visualize the immunoreactive proteins. Chemiluminescent signals on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane were recorded using a LAS-3000 imaging system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Purification of CrSGT1 Protein

All purification steps were performed at 4 °C. Buffers used were as follows: Buffer A, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, containing 10% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 500 mm NaCl; Buffer B, Buffer A containing 50 mm glycine; Buffer C, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, containing 10% glycerol and 0.1% Triton X-100; Buffer D, Buffer C containing 200 mm NaCl; Buffer E, 25 mm 1-methylpiperidine, pH 8.5, containing 10% glycerol and 0.1% Triton X-100; Buffer F, Buffer E containing 200 mm NaCl; Buffer G, 25 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, containing 10% glycerol, 0.5% CHAPS, and 500 mm NaCl; and Buffer H, 25 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, containing 10% glycerol and 0.5% CHAPS.

Step 1. Chelating Sepharose FF Chromatography

4 liters of CrP100 were applied to a column of chelating Sepharose FF (GE Healthcare) (inner diameter, 5 × 5 cm) charged with Ni2+ and equilibrated with Buffer A. After washing the column with Buffer A, enzyme was eluted with 500 ml of Buffer B.

Step 2. First DEAE-Sepharose FF Chromatography Step

The enzyme fraction obtained in step 1 was dialyzed against Buffer C and applied to a column of DEAE-Sepharose FF (GE Healthcare) (inner diameter, 1.5 × 11 cm) equilibrated with Buffer C. SGT was eluted with 0.2 liters of Buffer D increased linearly from 0 to 100%.

Step 3. Second DEAE-Sepharose FF Chromatography Step

The enzyme fraction obtained in step 2 was diluted 10-fold with Buffer E and then applied to a column of DEAE-Sepharose FF (GE Healthcare) (inner diameter, 0.7 × 13 cm) equilibrated with Buffer E. SGT was eluted with 50 ml of Buffer E increased linearly from 0 to 100%.

Steps 4 and 5. Sephadex G-200 Gel Filtration

The enzyme fraction obtained in step 3 was concentrated to 0.25 ml using a Microcon YM-30 filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and then applied to a Sephadex G-200 column (GE Healthcare) (inner diameter, 2.5 × 15 cm) equilibrated with Buffer G. SGT was eluted with the same buffer.

Step 6. Native PAGE

Native PAGE was performed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel (Wako, Osaka, Japan), at 4 °C according to the method of Ornstein-Davis method (41, 42). All lanes were cut into 5-mm pieces, and each slice was homogenized. Protein was extracted with 2.5 ml of Buffer H and then concentrated to 25 μl using a Microcon YM-30 filter (43).

Step 7. Isoelectric Focusing (IEF)-PAGE

IEF was performed on a pH 3–10 IEF gel (Invitrogen) at 4 °C. All lanes were cut into 5-mm pieces, and each slice was homogenized. Protein was extracted with 2.5 ml of Buffer H and then concentrated to 12 μl using a Microcon YM-30 filter.

Production of RNAi Construct and Transformation of Tobacco BY-2 Cells

The following methods were used for the preparation of an RNAi construct for NtSGT1. The intron 1 from castor bean catalase 1 gene (44) with BamHI and KpnI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, were amplified by PCR using 5′-GGCGGGATCCCTACAGGGTAAATTTCT-3′ and 5′-GGCGGGTACCGGTTCTGTAAC-3′ as primers and pIG121-Hm (45) as a template. The resultant fragment was digested with BamHI and KpnI and cloned into the multiple cloning site of pUC19 to yield pUC19-intron1. A fragment of NtSGT1 corresponding to the 296th and 844th position of the NtSGT1 cDNA with a SalI site at the 5′ end and BglII and SphI sites at the 3′ end was amplified by PCR using 5′-AGATTGTCGACTTGCACTGATGAAGAGAGGAAG-3′ and 5′-GAATAGCATGCAGATCTATCATCAAGTTATCATTAATC-3′ as primers and the NtSGT1 cDNA as a template. The resultant fragment was digested with SphI and SalI and cloned into the multiple cloning site of pUC19-intron1 to yield pUC19-SGT-intron1. Another fragment of NtSGT1 corresponding to the 296th and 844th position of the NtSGT1 cDNA with KpnI at the 5′ end and EcoRI and HindIII sites at the 3′ end was amplified by PCR using 5′-AGATTGGTACCTTGCACTGATGAAGAGAGGAAG-3′ and 5′-GAATAGAATTCAAGCTTATCATCAAGTTATCATTAATC-3′ as primers and the NtSGT1 cDNA as a template. The resultant fragment was digested with KpnI and EcoRI and cloned into the multiple cloning site of pUC19-SGT-intron1 to yield pUC19-SGT-intron1-TGS, which contains an inverted repeat of SGT fragments separated by the intron 1 of the catalase 1 gene. Thereafter, this plasmid was digested with BglII and HindIII, and the resultant fragment containing the RNAi construct was subcloned into the corresponding sites of pMAT037 (46), which is a binary vector containing the enhancer-duplicated CaMV35S promoter before the BglII and HindIII restriction sites. The resultant plasmid was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA101 (47) by electroporation and used for the transformation of tobacco BY-2 cells as described (46).

Analysis of the RNAi Effect

Identification of transformed tobacco cells that showed reduced expression level of NtSGT1 was analyzed as follows: independent colony of transformed tobacco cells or nontransformed BY-2 cells was introduced into suspension culture and subcultured weekly until the growth rate was stabilized. Five-day-old cells in suspension culture were collected by filtration, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder using a motor and pestle. Total RNA was extracted from the cell powder using RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as described in the manufacturer's instruction. The isolated RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) and used for the preparation of cDNA using Takara RNA PCR kit (AMV) (Takara Bio) as described in the manufacturer's instruction. An aliquot of the cDNA in solution was used as a template of PCR. Semi-quantitative analysis of the expression of NtSGT1 by PCR was carried out as follows. The NtSGT1 fragment corresponding to the 1st to 365th position was amplified using the cDNAs as a template and 5′-GGACACACAAACCTTTGACT-3′ and 5′-CCAGTTTTGGGATGTCTGCT-3′ as primers for 30 cycles using Takara EX TaqHS DNA polymerase (Takara Bio). For the reference of the expression level, a fragment of tobacco actin corresponding to the 527th to 984th position of actin cDNA from tobacco BY-2 cell (NCB accession number AB158612) was amplified using 5′-CAATTCTTCGGTTGGATCTTG-3′ and 5′-CTTCATGCTGCTGGGAG-3′ as primers for 20 cycles. The cycle numbers of PCRs used here were determined to show semi-quantitative amplification results by using varied amounts of cDNA from nontransformed BY-2 cells. After the PCR, DNA fragments were separated by agarose electrophoresis, stained by SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen), and the images of fluorescence of DNA recorded using a Typhoon 9600 image analyzer (GE Healthcare) using 532 nm excitation and 526SP emission filter at the protein mannosyltransferase voltage of 450 V. Thereafter, the intensity of the bands was quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare), and the ratio of the intensities of NtSGT1 and actin cDNA was calculated. Using this value, the three most suppressed lines among 18 lines were identified and used for the analysis of SGT1 activity.

For the analysis of SGT activity, microsomes were prepared from 7-day-old cells as follows. Cells were harvested on a filter paper by filtration using a Buchner funnel and suspended with an equal weight of ice-cold homogenization buffer consisting of 40 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 400 mm sorbitol, and 2 mm DTT. Cells were homogenized using a Potter-Elvehjem-type glass homogenizer. Homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The resultant pellet was suspended into the homogenization buffer and used for the microsomal fraction to measure the SGT activity.

Sucrose Gradient

Col-0 cells were grown for 14–20 days at 23 °C. All manipulations were done on ice or at 4 °C. Col-0 cells (1 g fresh weight) were homogenized with 10 ml of buffer containing 50 mm MOPS-NaOH, pH 7.0, EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics), and either 10 mm EDTA (Buffer L) or 10 mm MgCl2 (Buffer M). The suspensions were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The precipitants were suspended with Buffer L or Buffer M. The suspensions, containing 1.0 mg of protein, were loaded onto 20% sucrose. A discontinuous gradient was formed by adding 0.5 ml of Buffer L or M containing 55, 50, 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, and 20% sucrose. The gradient was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 18 h and collected in fractions of 280-μl increments. Specific membrane fractions were identified by immunoblotting using antibodies against organelle-specific markers.

RESULTS

Establishment of Peptidyl SGT Assay System

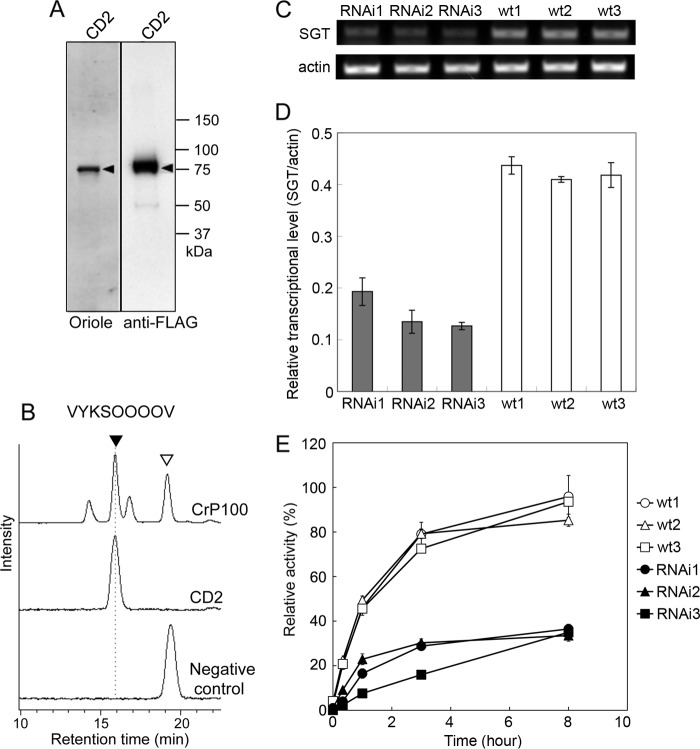

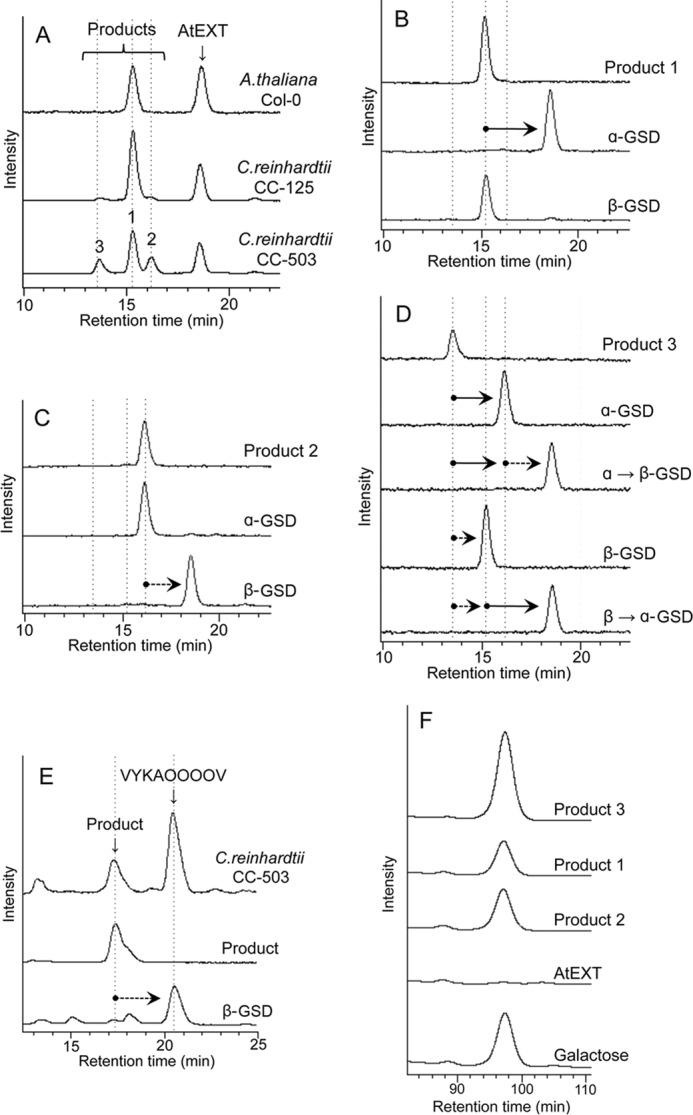

At first, we tried to clone SGT genes of plants based on an amino acid homology search in protein databases, but this approach was unsuccessful. In this case, conventional enzymatic purification strategy appeared to be the best way to obtain SGTs. For the purification of SGT, we chose C. reinhardtii, because biochemical approaches seem to be applicable more easily than in higher plants. A. thaliana was also used for the establishment of an SGT assay system. To establish the SGT assay system, we began by selecting suitable substrates. We synthesized common repetitive extensin peptides (AtEXT peptide, FITC-Ahx-VYKSOOOOV-NH2) as acceptors to measure SGT activity (48). C. reinhardtii (wild-type strain CC-125 and cell wall-less mutant strain CC-503) and A. thaliana (wild-type strain Columbia-0 (Col-0)) were used as enzyme sources. From cell cultures, microsomal fractions (P100) were prepared as crude enzymes. SGT assays were performed in the presence of the above synthetic peptide and UDP-galactose with detergent-solubilized P100 samples. The resulting reaction mixture was analyzed by HPLC. One major product was detected in P100 from Col-0 and CC-125, whereas multiple products (products 1–3) were detected in P100 from CC-503 (Fig. 1A). We had expected to observe a single O-linked galactose at the only serine residue in the AtEXT peptide, but the results indicated that more galactose residues were added in the case of CC-503.

FIGURE 1.

A, HPLC analysis of A. thaliana and C. reinhardtii peptidyl galactosyltransferase activity. P100 fractions were prepared from A. thaliana cells (Col-0), C. reinhardtii CC-125 cells, and C. reinhardtii cell wall-less mutant CC-503 cells. The P100 fraction (100 μg for A. thaliana or 10 μg for C. reinhardtii) was incubated with the assay mixture described under “Experimental Procedures” containing AtEXT peptide as an acceptor at 30 °C for 10 h (A. thaliana) or 3 h (C. reinhardtii) and then analyzed by HPLC. The acceptor peptide (AtEXT) was eluted at 18.8 min, and three enzymatic reaction products were detected, indicated as products 1, 2, and 3, at 15.2, 16.1, and 13.7 min, respectively (these are indicated with vertical broken lines in A–D). B–D, HPLC analysis of products after α- and β-galactosidase (GSD) treatment. B shows product 1 before and after galactosidase treatment, and C shows product 2 before and after treatment. D shows product 3 before and after treatment. α→β-GSD indicates product 3 treated with β-GSD after α-galactosidase treatment. β→α-GSD indicates product 3 treated with α-galactosidase after β-galactosidase treatment. The sequence of AtEXT peptide was FITC-Ahx-VYKSOOOOV-NH2. O indicates hydroxyproline. E, P100 fraction (10 μg) of C. reinhardtii CC-503 cells was incubated in an assay mixture containing VYKAOOOOV peptide as an acceptor at 30 °C for 3 h and then analyzed by HPLC. The product was collected and treated with β-galactosidase. F, monosaccharide analysis of products 1–3. In each case, 100 pmol of the products, the AtEXT peptide, and an authentic galactose standard were acid-hydrolyzed, labeled with PA (35), and analyzed by HPLC using a TSKgel sugar AXI column. PA-galactose was detected at 97 min, whereas PA-glucose and PA-mannose were detected at 55 and 62 min, respectively (data not shown).

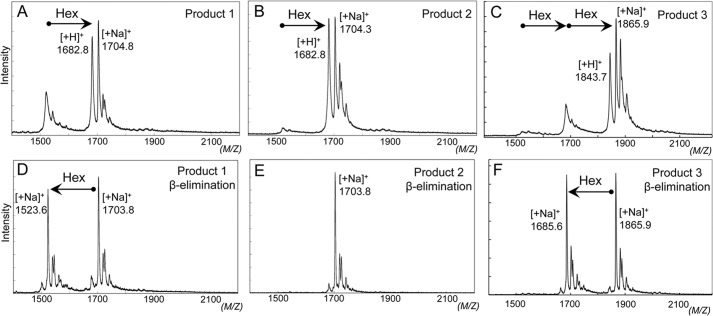

Structural Analysis of Enzymatic Reaction Products

Reaction products obtained with CC-503 microsomes were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Products 1 and 2 showed a single hexose addition (Fig. 2, A and B), and product 3 contained two hexoses attached to the AtEXT peptide (Fig. 2C). β-Elimination by alkaline reagents releases O-glycosylated sugars attached to serine or threonine residues but not to hydroxyproline (33). Each product was again analyzed by mass spectrometry after β-elimination. No sugars were released from product 2, but a single hexose was released from product 1 (Fig. 2, D and E). One hexose of two present was released from product 3 (Fig. 2F). These results indicate a single hexose attached to serine in product 1 and to hydroxyproline in product 2, and two hexoses attached to serine and hydroxyproline in product 3.

FIGURE 2.

Peptidyl galactosylated products were analyzed by β-elimination. A–C, mass spectra of hexosylated products 1–3, respectively. Signals from products 1 and 2 at m/z 1682.8 correspond to the molecular mass of a proton adduct of AtEXT peptide (Mr 1519.1) containing one hexose (Hex), whereas at m/z 1704.8 and m/z 1704.3 signals correspond to sodium adducts. A signal from product 3 at m/z 1843.7 corresponds to the molecular mass of a proton adduct of AtEXT peptide containing two hexoses, whereas that at m/z 1865.9 corresponds to a sodium adduct. D–F, mass spectra of products 1–3 after β-elimination, respectively. O-Glycosylated sugars attached to serine residues in the AtEXT peptide were eliminated, and dehydroalanine was produced from serine residues by a β-elimination reaction. Product 1 shifted to an ion at m/z 1523.6, which corresponds to the molecular mass of a sodium adduct of AtEXT peptide containing dehydroalanine, formed from serine (FITC-Ahx-VYK-Dha-OOOOV-NH2, Mr 1501.1; Dha and O indicate dehydroalanine and hydroxyproline, respectively) after β-elimination of hexose, indicating that product 1 was hexosylated at the serine residue. Product 2 showed no products by β-elimination, indicating that the product 2 was hexosylated at a Hyp residue. Product 3 shifted to an ion at m/z 1685.6, which corresponds to a sodium adduct of hexosylated AtEXT peptide containing dehydroalanine, formed from serine (FITC-Ahx-VYK-Dha-OOOO(-hexose)V-NH2, Mr 1663.1, hexose attached to one of four hydroxyprolines) after β-elimination of one hexose, indicating that product 3 was hexosylated at serine and Hyp residues.

Next, the products obtained with CC-503 microsomes were treated with α-galactosidase or β-galactosidase, and the resulting products were analyzed by HPLC. The peak of product 1 shifted to the position of AtEXT peptide after α-galactosidase treatment (Fig. 1B). In product 2, the peak shifted to the position of AtEXT peptide after β-galactosidase treatment (Fig. 1C). In product 3, the peak shifted to the position of product 2 after α-galactosidase treatment. Furthermore, the peak shifted to the position of the AtEXT peptide after an additional β-galactosidase treatment. The peak of product 3 also shifted to the position of product 1 after β-galactosidase treatment. Furthermore, the peak shifted to the position of the AtEXT peptide by an additional α-galactosidase treatment (Fig. 1D). When the peptide FITC-GABA-VYKAOOOOV-NH2, in which serine was replaced with alanine, was used as an acceptor, a single product peak was detected. The product was digestible by β-galactosidase (Fig. 1E). To confirm that the sugar that was added is galactose, the monosaccharides of the products were analyzed. Galactose, but not other hexoses, was detected in all products, whereas galactose was not detected in the AtEXT peptide. The amount of galactose attached to product 3 was 2-fold higher than that of product 1 or 2 (Fig. 1F). These results indicate that product 1 is an α-galactosylated AtEXT peptide O-linked at the serine residue (a result of SGT activity), that product 2 was a β-galactosylated AtEXT peptide O-linked at the Hyp residue (a result of HGT activity), and that product 3 had both structures. The continuous Hyp residues in extensin of plants were previously reported to be modified with O-arabinofuranose (21) and not galactose. Therefore, the detection of galactosylation of Hyp in AtEXT peptide appears to be quite unusual when the P100 fraction from Chlamydomonas cell wall-less mutant CC-503 was used for the enzyme source (see under “Discussion”).

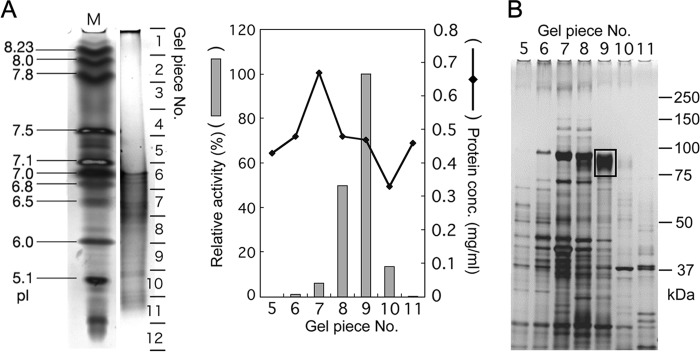

Partial Purification of SGT Protein from C. reinhardtii Cells

We chose C. reinhardtii cell wall-less mutant CC-503 for partial purification of the SGT protein, because a large amount of cell homogenate could be obtained from C. reinhardtii more easily than from A. thaliana. Cell wall-less mutation enables easy homogenization for the purification of SGT. Solubilized proteins from the P100 fraction of CC-503 were chromatographed on a series of columns as follows: a single run on a nickel-chelating Sepharose column, two runs on a DEAE-Sepharose column, and two runs on a Sephadex G-200 column (Table 1). The peak fraction of activity after the second Sephadex G-200 chromatography step was separated by native PAGE, and the gels were then sliced into 5-mm sections. The proteins from the section showing the highest SGT activity were further separated by IEF-PAGE, and the gels were sliced into 12 sections (Fig. 3A). The highest activity was detected in the ninth section by the IEF-PAGE. The proteins of each section were separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3B), and a major band at 80–90 kDa, the intensity of which corresponded well to the enzymatic activity, was observed predominantly in the ninth section (boxed in Fig. 3B).

TABLE 1.

Summary of purification of SGT protein prepared from C. reinhardtii cell wall-less mutant CC-503

| Step | Protein | Total activitya | Specific activitya | Recovery | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg | unit | unit/mg | % | -fold | |

| CrP100 | 10,570 | 528 | 0.05 | 100 | 1 |

| Nickel-chelating Sepharose | 749 | 292 | 0.39 | 55 | 7.8 |

| 1st DEAE-Sepharose | 70.9 | 130 | 1.83 | 25 | 36 |

| 2nd DEAE-Sepharose | 29.8 | 143 | 4.8 | 27 | 96 |

| 1st Sephadex G-200 | 1.5 | 23.4 | 15.6 | 4.4 | 312 |

| 2nd Sephadex G-200 | 0.68 | 6.3 | 9.2 | 1.2 | 184 |

| Native-PAGE | 0.212 | NDb | ND | ND | ND |

| IEF-PAGE | 0.0564 | 1.2 | 21.8 | 0.2 | 436 |

a One unit is the amount of enzyme required to transfer 1 nmol of galactose to AtEXT peptide within 1 min at 30 °C, pH 7.0.

b ND means not determined.

FIGURE 3.

PAGE of the SGT purification process. A, IEF-PAGE separation of proteins partially purified by native PAGE. One hundred percent corresponds to 11.1 units (nmol/min/mg protein) in the SGT assay with protein extracted from gel piece 9. B, SDS-PAGE of protein extracted from gel pieces 5–11 shown in A. Gel piece 9 showed the highest SGT activity, and an 80–90-kDa protein indicated by the box was recovered from the gel and then analyzed by MS/MS.

Cloning of Candidate C. reinhardtii SGT cDNA

The proteins recovered from the 80–90-kDa band were digested with trypsin, and their amino acid sequences were determined by tandem mass spectrometry. The amino acid sequences were matched with the CHLREDRAFT_150807 (NCB accession number XP_001696927) sequence of the Chlamydomonas proteome database (49). XP_001696927 is a protein with 717 aa and includes an N-terminal signal sequence and a C-terminal transmembrane region possessing type I membrane protein topology. A DNA fragment containing the XP_001696927 open reading frame was cloned from a cDNA library obtained from the Chlamydomonas Resource Center. The cloned DNA fragment encoded a 748-aa protein (NCB accession number BAL63043), 31 aa longer than the sequence registered in the database, having two insertions and one deletion (Fig. 4A, CrSGT1).

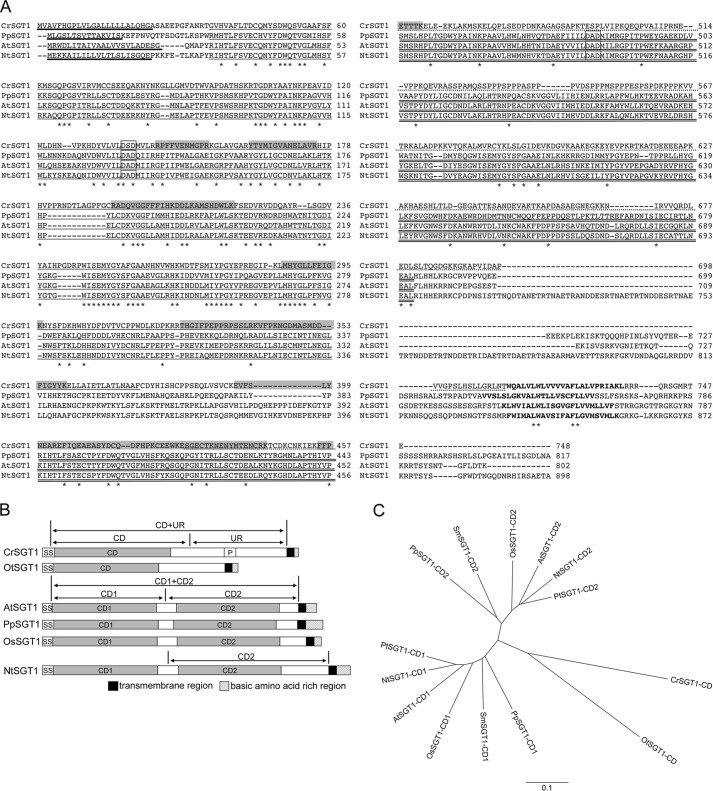

FIGURE 4.

A, alignment of predicted amino acid sequences of SGT1. In the CrSGT1 sequence, shaded areas indicate the peptides identified from the MS/MS analysis of the band shown in Fig. 3B. Boldface letters indicate transmembrane regions near the C terminus. Single and double lines indicate catalytic domains (CD1 and CD2, respectively). Broken lines indicate unknown regions (UR) in CrSGT1. Thick lines indicate signal sequences. Squares indicate the consensus DXD motif. Asterisks indicate conserved amino acid residues. The alignment was performed using the ClustalW2 program (67). B, schematic of domain structures of SGT1 protein of various species. SGT1s, including putative domains, of six species are shown. SS, signal sequence; CD, catalytic domain; P, proline-rich region; and UR, unknown region. Regions indicated by the arrows on CrSGT1, AtSGT1, and NtSGT1 were expressed as recombinant proteins by P. pastoris. C, phylogenic tree of catalytic domains in SGT. The phylogenic tree was calculated using the ClustalW2 program (67) and drawn by FigTree version 1.3.1 program. At, A. thaliana (NCB accession number NP_566148); Cr, C. reinhardtii (NCB accession number BAL63043); Nt, N. tabacum (NCB accession number BAL63045); Os, O. sativa (NCB accession number NP_001045124); Ot, O. tauri (NCB accession number XP_003074419); Pp, P. patens (NCB accession number XP_001775943); Pt, P. trichocarpa (NCB accession number XP_002298591); and Sm, S. moellendorffii (NCB accession number XP_002969342).

Confirmation of C. reinhardtii SGT1 Gene Product as Peptidyl SGT

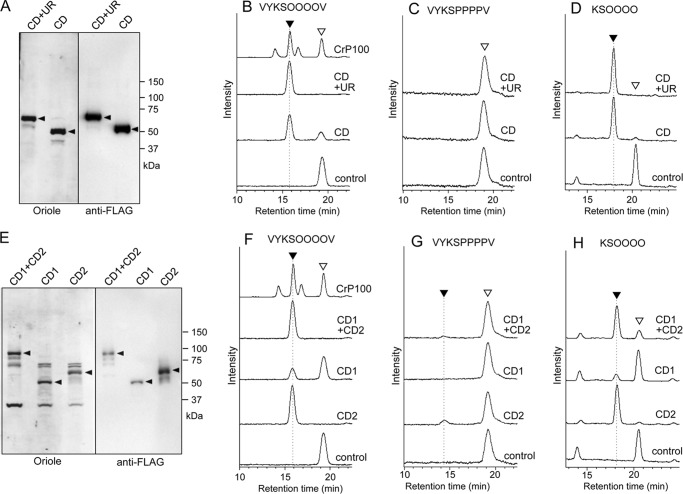

We predicted the catalytic domain (CD) of SGT based on a homology search (described below), the transmembrane region, and an unknown region (UR) of the candidate CrSGT1 protein (Fig. 4, A and B). Recombinant proteins of CD+UR or CD were both tagged with His6 and 3×FLAG tags at the N terminus and were expressed by P. pastoris cells, and the secreted proteins in the culture medium were purified using the affinity tags (Fig. 5A). An SGT assay was performed with 10 ng of recombinant protein and AtEXT peptide (FITC-Ahx-VYKSOOOOV-NH2). A single product peak was detected in the presence of CD or CD+UR protein (Fig. 5B). This product showed the same retention time by HPLC as product 1 in Fig. 1A. In contrast, when AtEXT-P peptide (FITC-Ahx-VYKSPPPPV-NH2) was used as an acceptor, no product peak was detected (Fig. 5C). This observation indicates that SGT recognizes the Hyp residues in the extensin repeat sequence. When AtEXTa peptide (FITC-GABA-KSOOOO-NH2) was used as an acceptor, a single product peak was detected in the presence of CD and CD+UR (Fig. 5D). These products were sensitive to α-galactosidase (data not shown), confirming that O-linked α-galactose was attached to the serine residue. From these results, we concluded that the gene that we characterized encodes a SGT; this gene was named CrSGT1.

FIGURE 5.

Expression of recombinant CrSGT1 and AtSGT1 and their enzymatic activity. A, recombinant CrSGT1 proteins were expressed by P. pastoris and then separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were stained using Oriole fluorescent gel stain (Bio-Rad). The anti-FLAG indicates Western detection of recombinant CrSGT1 proteins using an anti-FLAG tag antibody. Black arrowheads indicate recombinant CrSGT1 proteins. Expressed SGT regions (CD+UR and CD) are also shown in Fig. 4, A and B. B–D, recombinant CrSGT1 proteins (10 ng of CD+UR or CD) were incubated at 30 °C for 1 h with three types of acceptor peptides, and enzymatic products were analyzed by HPLC. The control was incubated with CD+UR treated at 95 °C for 10 min. Black and white arrowheads indicate enzymatic products of CrSGT1 and acceptor, respectively. The amino acid sequences of AtEXT, AtEXT-P, and AtEXTa peptides used as acceptors were, respectively, FITC-Ahx-VYKSOOOOV-NH2, FITC-Ahx-VYKSPPPPV-NH2, and FITC-GABA-KSOOOO-NH2. O indicates hydroxyproline. E, production of recombinant AtSGT1. Expressed recombinant proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were stained with Oriole fluorescent gel stain or subjected to immunoblot analysis. Recombinant AtSGT1 proteins were detected using an anti-FLAG tag antibody. Black arrowheads indicate recombinant AtSGT1 proteins. Expressed SGT regions (CD1+CD2, CD1, CD2) are also shown in Fig. 4, A and B. F–H, AtSGT1 proteins (200 ng of CD1+CD2, CD1, and CD2) expressed by P. pastoris were incubated at 30 °C for 12 h with three acceptor peptides, and enzymatic products were analyzed by HPLC. The control was incubated with CD1+CD2 treated at 95 °C for 10 min. Black and white arrowheads are same as B–D. B and F, a 10-μg P100 fraction of C. reinhardtii CC-503 was also used for galactosyltransferase activity assay as shown in Fig. 1A, which is indicated as CrP100.

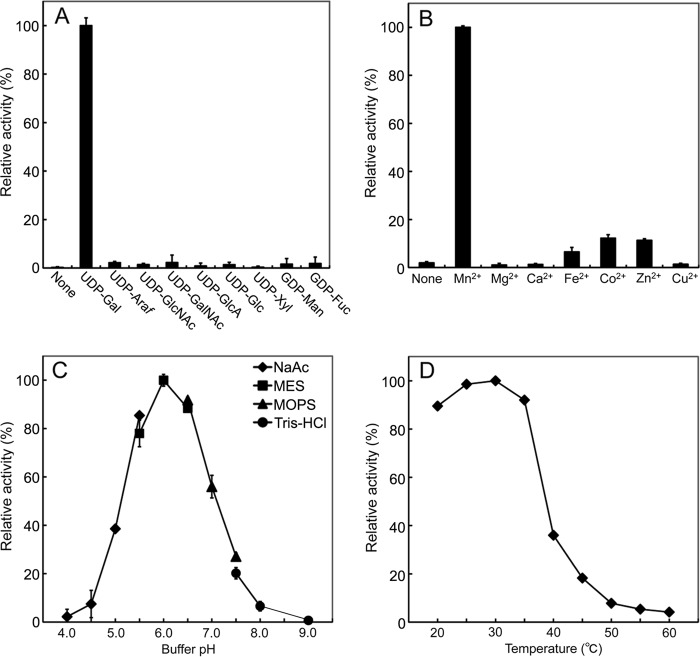

The activity of the SGT was characterized using CrSGT1-CD+UR recombinant protein. CrSGT1 selectively utilized UDP-galactose as a donor nucleotide sugar (Fig. 6A). CrSGT1 required Mn2+ for maximum activity, was inactive in the absence of divalent cations, and showed weak activity with Fe2+, Co2+, and Zn2+, and activity was absent with Mg2+, Ca2+, and Cu2+ (Fig. 6B). SGT had an optimal pH of 6.0 and an optimal reaction temperature of 30 °C (Fig. 6, C and D).

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of SGT activity of recombinant CrSGT1 (CD+UR) toward AtEXT peptide (n = 3). A, requirement for nucleotide sugars. Assay mixtures were incubated with or without 5 mm various nucleotide sugars. 100% corresponds to 6.4 × 102 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) with UDP-galactose. B, requirement for divalent metal cation. Assay mixtures were incubated with or without various divalent metals. 100% corresponds to 6.5 × 102 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) with manganese. C, optimal pH. Buffers for assay mixtures were 0.1 m sodium acetate (diamonds), 0.1 m MES-NaOH (squares), 0.1 m MOPS-NaOH (triangles), and 0.1 m Tris-HCl (circles). 100% corresponds to 6.0 × 102 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) at pH 6.0 of 0.1 m MES-NaOH. D, optimal temperature. Assay mixtures were incubated at 20–60 °C. 100% corresponds to 6.1 × 102 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) at 30 °C.

SGT1 Belongs to a Novel Glycosyltransferase Gene Family

A homology search for CrSGT1 revealed the presence of predicted type I proteins that have the CD in various plants, including A. thaliana (802 aa, NCB accession number NP_566148), Oryza sativa (814 aa, NCB accession number NP_001045124), Ricinus communis (817 aa, NCB accession number XP_002526934), Vitis vinifera (817 aa, NCB accession number XP_002271170), Populus trichocarpa (797 aa, NCB accession number XP_002298591), Selaginella moellendorffii (820 aa, NCB accession number XP_002969342), Physcomitrella patens (817 aa, NCB accession number XP_001775943; 816 aa, NCB accession number XP_001764357), and Ostreococcus tauri (571 aa, NCB accession number XP_003074419). Except for P. patens, each plant had one copy of the CrSGT1 homolog. The sequences in unicellular algae, including O. tauri and C. reinhardtii had one catalytic domain, whereas multicellular plants had two CDs. The C. reinhardtii CD is ∼36–38% identical to CD1s and CD2s of multicellular plants (Table 2). According to the phylogenetic tree, CD1s and CD2s form different clusters (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that each CD of SGT1 may have been duplicated in a primitive plant after unicellular algae, and it evolved independently during the evolution of higher plants. No proteins with the CD were found in animals or fungi, indicating that SGT is unique to the plant kingdom.

TABLE 2.

Amino acid sequence identity of SGT1 catalytic domains between C. reinhardtii and multicellular plants

Catalytic domain of C. reinhardtii (CrCD in BAL63043) is compared with catalytic domain 1 (CD1) and catalytic domain 2 (CD2) of multicellular plants (P. patens XP_001775943, S. moellendorffii XP_002969342, O. sativa NP_001045124, A. thaliana NP_566148, N. tabacum BAL63045, and P. trichocarpa XP_002298591).

| P. patens | S. moellendorffii | O. sativa | A. thaliana | N. tabacum | P. trichocarpa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrCD vs. CD1 | 38.1% | 38.4% | 37.0% | 37.5% | 36.2% | 36.6% |

| CrCD vs. CD2 | 36.8% | 37.3% | 36.1% | 37.6% | 37.2% | 37.1% |

To investigate SGT activity and substrate specificity of two CDs of the multicellular plant, we obtained a cDNA clone for A. thaliana homolog At3g01720 from the RIKEN BioResource Center, and we expressed its lumenal region (CD1+CD2, CD1, and CD2) in Pichia (Fig. 5E). Using AtEXT peptide as a substrate, a single peak product was detected on HPLC, which eluted at the same position as product 1 in Fig. 1A (Fig. 5F). In contrast, when AtEXT-P peptide was used as an acceptor, a product peak was barely detected (Fig. 5G), indicating that SGT of A. thaliana also recognizes hydroxyproline in the substrate, and these products show again that it is serine that is modified with galactose. When AtEXTa peptide was used as an acceptor, a single product peak was detected (Fig. 5H). These products had sensitivity to α-galactosidase (data not shown), indicating that the protein (NP_566148) encoded by At3g01720 (designated as AtSGT1) also possesses SGT activity. In addition to the AtEXTa peptide (FITC-GABA-KSOOOO-NH2), three synthetic peptides (FITC-GABA-HSOOOO-NH2, FITC-GABA-SSOOOO-NH2, and FITC-GABA-YSOOOO-NH2), containing sequences found in A. thaliana extensins 2–5 (AtEXT2–5), were also used as acceptors (48). CD1+CD2 showed higher SGT activity against YSOOOO and KSOOOO peptides than other peptides (Table 3). CD1 and CD2 showed higher SGT activity against YSOOOO and KSOOOO, respectively (Table 3). These results indicate that an amino acid residue adjacent to the serine residue has an influence on the substrate specificity of SGT1 and that CD1 and CD2 have different preferences about amino acid sequence.

TABLE 3.

Substrate specificity of recombinant AtSGT1

AtSGT1 proteins (200 ng of either CD1 + CD2, CD1, or CD2) expressed by P. pastoris were incubated at 30 °C for 6 h with four acceptor peptides, and enzymatic products were analyzed by HPLC. Peak areas of substrate and product were calculated, and SGT activity was shown as percentage of the product (the total amount of substrate and product was set as 100% in each experiment). KSOOOO, HSOOOO, SSOOOO, and YSOOOO indicate experiments using FITC-GABA-KSOOOO-NH2 (AtEXTa), FITC-GABA-HSOOOO-NH2, FITC-GABA-SSOOOO-NH2, and FITC-GABA-YSOOOO-NH2, respectively, as the acceptor.

| Expressed region | Activity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KSOOOO | HSOOOO | SSOOOO | YSOOOO | |

| % | ||||

| CD1+CD2 | 63.2 | 19.6 | 49.0 | 94.1 |

| CD1 | 12.1 | 6.1 | 15.8 | 57.4 |

| CD2 | 90.7 | 27.0 | 17.2 | 24.9 |

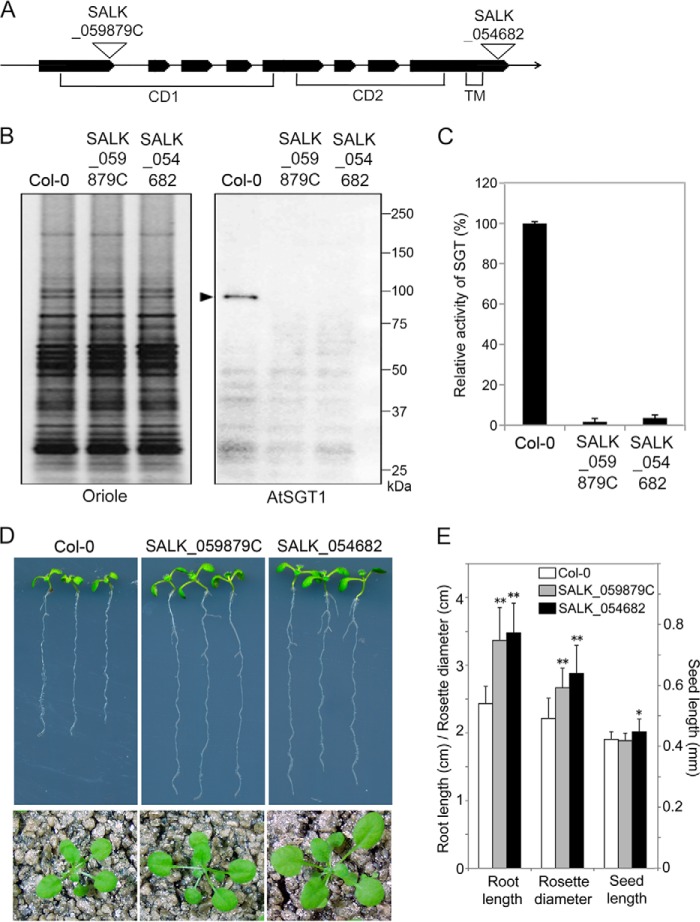

We also cloned N. tabacum SGT1 cDNA (encoding NtSGT1, 898 aa, NCB accession number BAL63045) from cDNA prepared from tobacco BY-2 cells (Fig. 4, A and B), and we confirmed that the encoded protein has SGT activity using a recombinant CD2 region expressed in Pichia (Fig. 7, A and B).

FIGURE 7.

In vitro and in vivo characterization of NtSGT1. A, production of recombinant NtSGT1. Expressed recombinant proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were stained using Oriole fluorescent gel stain. Proteins were also subjected to immunoblot analysis, and recombinant NtSGT1 proteins were detected using an anti-FLAG tag antibody. Black arrowheads indicate recombinant NtSGT1 protein. CD2 indicates NtSGT1 without N-terminal signal sequence, CD1, and C-terminal transmembrane region. Expressed SGT regions are shown in Fig. 4, A and B. B, NtSGT1 protein (200 ng CD2) expressed by P. pastoris was incubated at 30 °C for 1 h with AtEXT peptide as an acceptor, and enzymatic products were analyzed by HPLC. The negative control was incubated with CD2 treated at 95 °C for 10 min. Black and white arrowheads indicate enzymatic products of NtSGT1 and acceptor, respectively. The P100 fraction (10 μg) of C. reinhardtii CC-503 was also incubated with an assay mixture containing AtEXT peptide as an acceptor at 30 °C for 3 h, shown by CrP100. C, RNAi of NtSGT1 expression. The expression level of NtSGT1 was analyzed by reverse transcriptase-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from the NtSGT1-suppressed cells (RNAi) and BY-2 cells (wt) cultured for 8 days. Oligo(dT)15 primers were used for reverse transcription. D, relative transcription level normalized to the transcription of actin (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). E, relative SGT activity (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). An SGT assay was carried out with 0.1 mg of the membrane fraction from NtSGT1-suppressed cells (RNAi), and wild-type cells were incubated for 20 min and 1, 3, and 8 h at 30 °C. 100% corresponds to 0.3 × 10−3 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) incubated for 8 h with membrane fraction extracted from wt1.

Properties of SGT and SGT1 Mutants in Plants

As AtSGT1 was unique and no related genes were observed in the A. thaliana genome, we examined the properties of SGT1 mutants of Arabidopsis. We obtained a confirmed tDNA insertion line of AtSGT1 (SALK_059879C and SALK_054682) from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Fig. 8A). Isolated homozygous tDNA insertion plants were used as AtSGT1 mutants. We then prepared microsomal fractions from the AtSGT1 mutant and wild-type Col-0 cells and compared the presence of SGT protein and SGT activity in these fractions. A specific antibody against a synthetic peptide that corresponds to a C-terminal cytosolic region of AtSGT recognized a 91-kDa polypeptide in the membrane fraction from Arabidopsis Col-0 cells, but no such polypeptide was detected in microsomal proteins from the tDNA insertion lines (Fig. 8B). Likewise, AtSGT1 mutant cells had negligible SGT activity (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Analysis of AtSGT1 mutant cells. SALK_059879C and SALK_054682 have tDNA insertion mutations in the AtSGT1 gene. A, insertion position of tDNA in SALK_059879C and SALK_054682. An arrow shows the genome region of AtSGT1 schematically; bold lines and thin lines represent exons and introns, respectively. CD1 and CD2 indicate catalytic domains, and TM indicates a transmembrane region. B, biochemical analyses of AtSGT1 mutant cells. P10 fraction (5 μg) from Col-0 and AtSGT1 mutant cells were separated by SDS-PAGE. Oriole shows proteins stained using Oriole fluorescent gel stain. AtSGT1 shows Western detection using anti-AtSGT1 antibody. A black arrowhead indicates AtSGT1 protein. C, SGT activity was assayed with 100 μg of P10 fractions from Col-0 and AtSGT1 mutant cells incubated with AtEXT peptide as an acceptor for 10 h at 30 °C, and the amount of SGT product was analyzed by HPLC. 100% corresponds to 3.0 × 10−3 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) in assay with 100 μg of P10 fraction from Col-0 (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). D, 8-day-old seedlings on solid Murashige and Skoog medium containing 3% sucrose and 0.8% agar (upper panels) and 3-week-old plants on soil (lower panels). E, comparison of root length of 8-day-old seedlings (mean ± S.D.; n = 8), rosette diameter of 3-week-old seedlings (mean ± S.D.; n = 15), and seed length (mean ± S.D.; n = 30) of Col-0 and AtSGT1 mutants. *, p < 0.01, and **, p < 0.0005, indicate significant differences from Col-0.

To gain knowledge about the physiological influence of loss-of-function mutation in SGT on plants, we grew AtSGT1 mutant plants and analyzed morphological phenotypes. AtSGT1 mutants, especially in the vegetative stage, exhibited a phenotype of longer roots and larger leaves than Col-0 (Fig. 8, D and E). The reason for these phenotypes will be discussed later (see “Discussion”).

Next, we transformed tobacco BY-2 cells to express an RNAi construct for NtSGT1. We then isolated transformed cell lines showing less expression of NtSGT1 mRNA, and we observed reduced SGT activity compared with untransformed cells (Fig. 7, C–E), indicating that NtSGT1 is the sole or major SGT protein in tobacco.

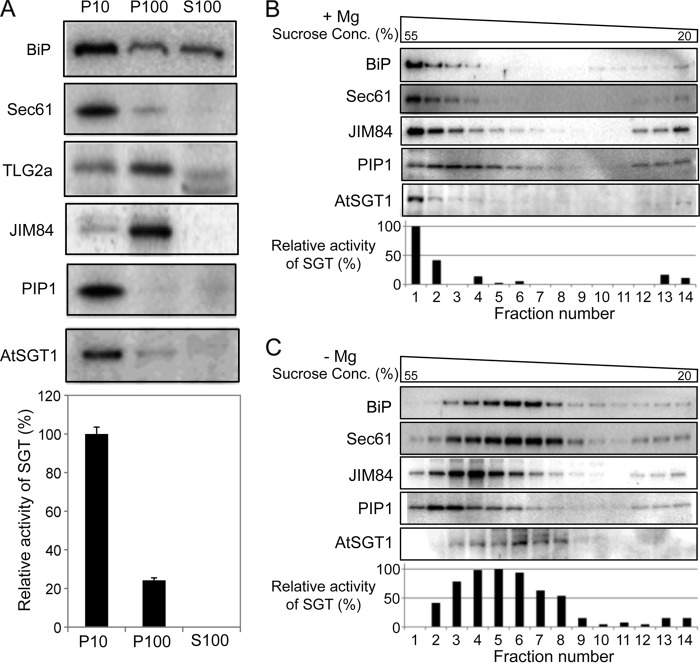

To determine the localization of AtSGT1 in Arabidopsis cells, we prepared fractions termed P10 (an ER and plasma membrane-enriched fraction), P100 (a Golgi-enriched fraction), and S100 (a cytosol-enriched fraction) from Col-0 cells and analyzed AtSGT1 and marker proteins by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. AtSGT1 protein was predominantly observed in the P10 fraction, and SGT activity was also detected mainly in the P10 fraction (Fig. 9A). To address the localization of AtSGT1 more precisely, we used sucrose density gradient centrifugation (Fig. 9, B and C). In the absence of Mg2+, the pattern of migration of AtSGT1 and SGT activity could be detected in fractions 2–8. This pattern was similar to that observed for Sec61 and BiP, markers for the ER membrane. Because it is known that the density of the ER membrane changes depending on the presence of Mg2+, these results indicate that, like the ER markers BiP and Sec61, AtSGT1 is predominantly localized to the ER membrane.

FIGURE 9.

Subcellular localization of AtSGT1. A, subcellular fractionation of AtSGT1. P10, P100, and S100 fractions were prepared from Col-0 cells, and AtSGT1 and various markers were detected by immunoblotting with specific antibodies that recognize BiP or Sec61 (for the ER membrane), TLG2a or JIM84 (Golgi apparatus), PIP1 (plasma membrane), and AtSGT1. SGT activity in each fraction was also shown. 100% corresponds to 9.5 × 10−3 unit (nmol/min/mg protein) incubated with P10 fraction extracted from Col-0 for 10 h. B and C, total protein extract (excluding cell debris) was prepared from Col-0 cells in buffers containing either Mg2+ (+Mg) or EDTA (−Mg). After sucrose density gradient centrifugation, the sample was separated into 14 fractions. The presence of AtSGT1 in these fractions was determined by immunoblotting and measurement of SGT activity. The distribution of marker proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting. 100% corresponds to 14.8 × 10−6 units and 26.8 × 10−6 units (nmol/min/fraction) incubated with fraction 1 in B and fraction 5 in C for 10 h, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We identified the gene for peptidyl serine O-galactosyltransferase, designated CrSGT1, through amino acid sequence analysis of purified C. reinhardtii SGT protein. CrSGT1 homologs were found in all plant genomes reported. SGT1 cDNA from C. reinhardtii, A. thaliana, and N. tabacum was cloned, and SGT activity of the encoded proteins was confirmed in yeast expression systems, indicating that SGT1 is widely distributed from unicellular algae to higher plants. The catalytic domains (CD2s) of SGT1 shared ∼82% amino acid identity among dicotyledonous plants, 77% between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants, and 37% between angiospermous plants and green algae (Fig. 4, A and B, and Table 2). SGT1 from all plants possessed a signal peptide and one or more catalytic domains, followed by transmembrane and cytosolic regions showing type I membrane protein topology, and it is the first known example of a glycosyltransferase with this membrane orientation (Fig. 4B).

In the Carbohydrate-Active EnZYme Database, glycosyltransferase genes are classified as GTs (for glycosyltransferase) according to homology (50). N-Glycans undergo a series of highly coordinated step-by-step enzymatic conversions occurring in the ER and Golgi apparatus. N-Glycosylation is highly conserved in all eukaryotes, including animals, plants, and fungi (51–55). In contrast, neither protein O-mannosyltransferases (protein mannosyltransferase/protein O-mannosyltransferase, GT39) (56, 57), which are involved in O-mannosylation in fungi and animals, nor polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases (ppGalNAcTs, GT27) (58), which are involved in complex-type O-glycan synthesis in animals, have been found in plants. Instead, plants appear to have several unique O-glycosyltransferase activities, including those of SGT, HGT, and HPAT. Among these O-glycosyltransferase proteins, HGT and HPAT are classified in GT31 and GT8, respectively, whereas SGT1 has not been classified as a member of any reported GT family in the Carbohydrate-Active EnZYme Database. These observations indicated that some of the genes for O-glycosylation evolved independently after separation of these kingdoms.

Use of a cell wall-less strain (CC-503) to enable easy homogenization made possible the partial purification and identification of the CrSGT1 gene. When we used CrP100 of CC-503 as an enzyme source, galactosylation of Hyp in addition to Ser was detected. According to the previous report, continuous Hyp residues in extensin of plants were modified with O-arabinofuranose (21). Therefore, the galactosylation of Hyp in an extensin motif is an unexpected result. In wild-type strain CC-125, peaks of products 2 and 3, indicating the galactosylation of Hyp, are very small but detectable, indicating that the galactosylation of Hyp occurs even in wild-type cells. It is possible that Hyp galactosyltransferase activity in CC-503 is hyperactivated to compensate for the cell wall defect. Because the galactosylation of Hyp was observed using an artificial acceptor substrate (AtEXT peptide), it remains to be elucidated whether Hyp residues in extensins are indeed galactosylated in vivo. Further study would be required to uncover mechanisms and physiological roles of the galactosylation of Hyp in the extensin motif.

An important issue is that the SGT activity is due to a single SGT gene in each plant species. To approach this issue, we tried structural analysis of Ser-O-αGal in AtSGT1 mutant plants by several methods, including quantitation of galactose after α-galactosidase digestion or β-elimination. We also prepared extensin-rich fractions from BY-2 cells and NtSGT1-suppressed cells according to a published method (59), digested them by α-galactosidase, and measured the amount of released galactose. However, reliable results were not obtained by these methods (data not shown). Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that other serine O-α-galactosyltransferases exist, which have no amino acid sequence homology to the SGTs reported here.

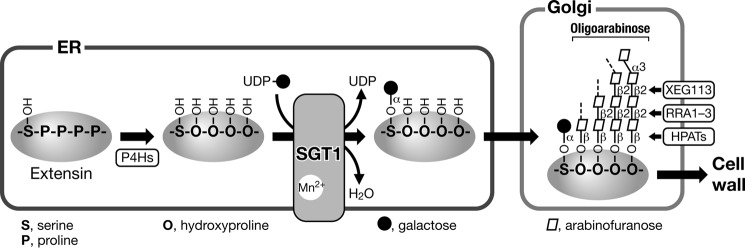

A hypothetical model of the extensin biosynthetic pathway in plant cells is shown in Fig. 10. Analysis of the localization of AtSGT1 in Arabidopsis cells indicated that AtSGT1 is predominantly localized to the ER membrane in this study. P4H is reportedly a resident protein in the lumen of the ER in vertebrate and mammalian cells (60–62), whereas P4H is detectable not only in the ER but also in the Golgi apparatus in N. tabacum BY-2 cells (39). Because SGT recognizes hydroxyproline in the substrate, SGT must be located further downstream of the protein transport pathway than P4H. BecauseTLG2a and JIM84 antibodies are trans-Golgi but not cis-Golgi markers, it remains possible that the SGT is localized not only in the ER but also in the cis-Golgi.

FIGURE 10.

Schematic diagram of the SGT1 reaction. The proline residues of extensin motif (-SPPPP-) are hydroxylated by P4Hs to yield hydroxyproline residues in the ER. Subsequently, serine residues are modified with galactose by SGT1. The SGT1 reaction requires manganese ion and uses UDP-galactose as a donor substrate. After extensins are transported to the Golgi apparatus, oligoarabinose structures were assembled. After hydroxyproline residues are modified with β-arabinofuranose by HPAT1–3 (hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferase; At5g25265, At2g25260, and At5g13500), another β-1,2-linked arabinofuranose is transferred by RRA1–3 (reduced residual arabinose 1–3; At1g75120, At1g75110, and At1g19360), and then XEG113 (At2g35610) further transfers β-1,2-linked arabinofuranose (24). Extensins are then transported and incorporated into the cell wall. Bold arrows indicate the protein transport pathway in plant cells.

The glycosyltransferases (SGT, HPATs, RRA, and XEG113), P4Hs, and extensins shown in Fig. 10 appear to be highly co-expressed with each other. A co-expression search using the PlaNet transcriptome co-expression platform (63) and the ATTED-II database (64–66) showed co-expression of AtSGT1 (At3g01720), RRA3 (At1g19360), XEG113 (At2g35610), HPAT3 (At5g13500), and two P4H genes (At2g17720 and At3g06300). The pattern of AtSGT1 expression in the PlaNet dataset showed higher expression in roots of 17- and 21-day seedlings, as well as at ∼0.30 to 2 mm from the root tip. In the same dataset, 16 out of 22 extensin genes showed a similar expression pattern, whereas only a small fraction of AGP genes showed such a pattern (supplemental Table 1). In the dataset in ATTED-II, AtSGT1 is highly co-expressed with P4H5, RRA3, and XEG113 in tissue, abiotic stress, and hormone-response conditions, respectively. The co-expression of these genes indicates that they might cooperatively act to glycosylate extensins.

AtSGT1 mutants exhibited longer roots and larger rosettes than wild type (Fig. 8, D and E). It does not seem that these phenotypes resulted from better growth than wild type. Extensins are considered to reinforce cell walls by fixing the distance of fine cellulose fibers and to have a role as negative regulator of cell extension (27). Perhaps the extensins presumably altered in the mutant are responsible for producing a more extensible cell wall resulting in longer roots and larger rosettes. These phenotypes are different from that of mutants with defects in hydroxyproline arabinosylation (23, 24), indicating that O-α-galactosylation of serine residues in extensins plays a different role. Although we think the longer roots and the larger rosettes are caused by the loss of function of the extensins, more extensive phenotypic analysis must be essential to elucidate the physiological functions of extensins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Chiba, T. Kitajima, and A. Kameyama for their technical advice.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

This article contains supplemental Table S1.

- AGP

- arabinogalactan protein

- HRGP

- hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein

- P4H

- prolyl-4-hydroxylase

- Hyp

- hydroxyproline

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- HGT

- hydroxyproline O-galactosyltransferase

- HPAT

- hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferase

- SGT

- serine-O-galactosyltransferase

- Ahx

- ϵ-amino caproic acid sequence

- PA

- pyridylamino

- IEF

- isoelectric focusing

- CD

- catalytic domain

- UR

- unknown region

- GT

- glycosyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Showalter A. M. (1993) Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant Cell 5, 9–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kieliszewski M. J., Lamport D. T. (1994) Extensin: repetitive motifs, functional sites, post-translational codes, and phylogeny. Plant J. 5, 157–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nothnagel E. A. (1997) Proteoglycans and related components in plant cells. Int. Rev. Cytol. 174, 195–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cassab G. I. (1998) Plant cell wall proteins. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 281–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seifert G. J., Roberts K. (2007) The biology of arabinogalactan proteins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58, 137–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kieliszewski M. J., Shpak E. (2001) Synthetic genes for the elucidation of glycosylation codes for arabinogalactan-proteins and other hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 1386–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matsuoka K., Watanabe N., Nakamura K. (1995) O-Glycosylation of a precursor to a sweet potato vacuolar protein, sporamin, expressed in tobacco cells. Plant J. 8, 877–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shimizu M., Igasaki T., Yamada M., Yuasa K., Hasegawa J., Kato T., Tsukagoshi H., Nakamura K., Fukuda H., Matsuoka K. (2005) Experimental determination of proline hydroxylation and hydroxyproline arabinogalactosylation motifs in secretory proteins. Plant J. 42, 877–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oka T., Saito F., Shimma Y., Yoko-o T., Nomura Y., Matsuoka K., Jigami Y. (2010) Characterization of endoplasmic reticulum-localized UDP-d-galactose: hydroxyproline O-galactosyltransferase using synthetic peptide substrates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152, 332–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan L., Leykam J. F., Kieliszewski M. J. (2003) Glycosylation motifs that direct arabinogalactan addition to arabinogalactan-proteins. Plant Physiol. 132, 1362–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Basu D., Liang Y., Liu X., Himmeldirk K., Faik A., Kieliszewski M., Held M., Showalter A. M. (2013) Functional identification of a hydroxyproline-O galactosyltransferase specific for arabinogalactan-protein biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10132–10143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liang Y., Faik A., Kieliszewski M., Tan L., Xu W. L., Showalter A. M. (2010) Identification and characterization of in vitro galactosyltransferase activities involved in arabinogalactan-protein glycosylation in tobacco and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154, 632–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu Y., Williams M., Bernard S., Driouich A., Showalter A. M., Faik A. (2010) Functional identification of two nonredundant Arabidopsis α(1,2)fucosyltransferases specific to arabinogalactan proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13638–13645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan L., Varnai P., Lamport D. T., Yuan C., Xu J., Qiu F., Kieliszewski M. J. (2010) Plant O-hydroxyproline arabinogalactans are composed of repeating trigalactosyl subunits with short bifurcated side chains. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24575–24583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fincher G. B., Stone B. A., Clarke A. E. (1983) Arabinogalactan-proteins: structure, biosynthesis, and function. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 34, 47–70 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Showalter A. M. (2001) Arabinogalactan-proteins: structure, expression and function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 1399–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahendran T., Williams P. A., Phillips G. O., Al-Assaf S., Baldwin T. C. (2008) New insights into the structural characteristics of the arabinogalactan-protein (AGP) fraction of gum arabic. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 9269–9276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Du H., Clarke A. E., Bacic A. (1996) Arabinogalactan-proteins: a class of extracellular matrix proteoglycans involved in plant growth and development. Trends Cell Biol. 6, 411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Motose H., Sugiyama M., Fukuda H. (2004) A proteoglycan mediates inductive interaction during plant vascular development. Nature 429, 873–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Hengel A. J., Tadesse Z., Immerzeel P., Schols H., van Kammen A., de Vries S. C. (2001) N-Acetylglucosamine and glucosamine-containing arabinogalactan proteins control somatic embryogenesis. Plant Physiol. 125, 1880–1890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shpak E., Barbar E., Leykam J. F., Kieliszewski M. J. (2001) Contiguous hydroxyproline residues direct hydroxyproline arabinosylation in Nicotiana tabacum. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11272–11278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ashford D., Desai N. N., Allen A. K., Neuberger A., O'Neill M. A., Selvendran R. R. (1982) Structural studies of the carbohydrate moieties of lectins from potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers and thorn-apple (Datura stramonium) seeds. Biochem. J. 201, 199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ogawa-Ohnishi M., Matsushita W., Matsubayashi Y. (2013) Identification of three hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 726–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Velasquez S. M., Ricardi M. M., Dorosz J. G., Fernandez P. V., Nadra A. D., Pol-Fachin L., Egelund J., Gille S., Harholt J., Ciancia M., Verli H., Pauly M., Bacic A., Olsen C. E., Ulvskov P., Petersen B. L., Somerville C., Iusem N. D., Estevez J. M. (2011) O-Glycosylated cell wall proteins are essential in root hair growth. Science 332, 1401–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gille S., Hänsel U., Ziemann M., Pauly M. (2009) Identification of plant cell wall mutants by means of a forward chemical genetic approach using hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14699–14704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Waffenschmidt S., Woessner J. P., Beer K., Goodenough U. W. (1993) Isodityrosine cross-linking mediates insolubilization of cell walls in Chlamydomonas. Plant Cell 5, 809–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lamport D. T., Kieliszewski M. J., Chen Y., Cannon M. C. (2011) Role of the extensin superfamily in primary cell wall architecture. Plant Physiol. 156, 11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodrum L. J., Patel A., Leykam J. F., Kieliszewski M. J. (2000) Gum arabic glycoprotein contains glycomodules of both extensin and arabinogalactan-glycoproteins. Phytochemistry 54, 99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kieliszewski M. J., O'Neill M., Leykam J., Orlando R. (1995) Tandem mass spectrometry and structural elucidation of glycopeptides from a hydroxyproline-rich plant cell wall glycoprotein indicate that contiguous hydroxyproline residues are the major sites of hydroxyproline O-arabinosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2541–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lamport D. T., Katona L., Roerig S. (1973) Galactosylserine in extensin. Biochem. J. 133, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allen A. K., Desai N. N., Neuberger A., Creeth J. M. (1978) Properties of potato lectin and the nature of its glycoprotein linkages. Biochem. J. 171, 665–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adair W. S., Snell W. J. (1990) in Organization and Assembly of Plant and Animal Extracellular Matrix (Adair W. S., Mecham R. P., eds.) pp. 15–84, Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wells L., Vosseller K., Cole R. N., Cronshaw J. M., Matunis M. J., Hart G. W. (2002) Mapping sites of O-GlcNAc modification using affinity tags for serine and threonine post-translational modifications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Natsuka S. (2011) A convenient purification method for pyridylamino monosaccharides. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75, 1405–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hase S., Hatanaka K., Ochiai K., Shimizu H. (1992) Improved method for the component sugar analysis of glycoproteins by pyridylamino sugars purified with immobilized boronic acid. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 56, 1676–1677 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bertioli D. (1997) Rapid amplification of cDNA ends. Methods Mol. Biol. 67, 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gietz R. D., Woods R. A. (2002) Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 350, 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ohshima Y., Iwasaki I., Suga S., Murakami M., Inoue K., Maeshima M. (2001) Low aquaporin content and low osmotic water permeability of the plasma and vacuolar membranes of a CAM plant Graptopetalum paraguayense: comparison with radish. Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 1119–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yuasa K., Toyooka K., Fukuda H., Matsuoka K. (2005) Membrane-anchored prolyl hydroxylase with an export signal from the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant J. 41, 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bassham D. C., Sanderfoot A. A., Kovaleva V., Zheng H., Raikhel N. V. (2000) AtVPS45 complex formation at the trans-Golgi network. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2251–2265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ornstein L. (1964) Disc electrophoresis. I. Background and theory. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 121, 321–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davis B. J. (1964) Disc electrophoresis. II. Method and application to human serum proteins. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 121, 404–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ishimizu T., Sano K., Uchida T., Teshima H., Omichi K., Hojo H., Nakahara Y., Hase S. (2007) Purification and substrate specificity of UDP-d-xylose:β-d-glucoside α-1,3-d-xylosyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of the Xyl α1–3Xyl α1–3Glc β1-O-Ser on epidermal growth factor-like domains. J. Biochem. 141, 593–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suzuki M., Ario T., Hattori T., Nakamura K., Asahi T. (1994) Isolation and characterization of two tightly linked catalase genes from castor bean that are differentially regulated. Plant Mol. Biol. 25, 507–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanaka A., Mita S., Ohta S., Kyozuka J., Shimamoto K., Nakamura K. (1990) Enhancement of foreign gene expression by a dicot intron in rice but not in tobacco is correlated with an increased level of mRNA and an efficient splicing of the intron. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6767–6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matsuoka K., Nakamura K. (1991) Propeptide of a precursor to a plant vacuolar protein required for vacuolar targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 834–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hood E. E., Helmer G. L., Fraley R. T., Chilton M. D. (1986) The hypervirulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens A281 is encoded in a region of pTiBo542 outside of T-DNA. J. Bacteriol. 168, 1291–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yoshiba Y., Aoki C., Iuchi S., Nanjo T., Seki M., Sekiguchi F., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2001) Characterization of four extensin genes in Arabidopsis thaliana by differential gene expression under stress and non-stress conditions. DNA Res. 8, 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Merchant S. S., Prochnik S. E., Vallon O., Harris E. H., Karpowicz S. J., Witman G. B., Terry A., Salamov A., Fritz-Laylin L. K., Maréchal-Drouard L., Marshall W. F., Qu L. H., Nelson D. R., Sanderfoot A. A., Spalding M. H., Kapitonov V. V., Ren Q., Ferris P., Lindquist E., Shapiro H., Lucas S. M., Grimwood J., Schmutz J., Cardol P., Cerutti H., Chanfreau G., Chen C. L., Cognat V., Croft M. T., Dent R., Dutcher S., Fernández E., Fukuzawa H., Gonzalez-Ballester D., González-Halphen D., Hallmann A., Hanikenne M., Hippler M., Inwood W., Jabbari K., Kalanon M., Kuras R., Lefebvre P. A., Lemaire S. D., Lobanov A. V., Lohr M., Manuell A., Meier I., Mets L., Mittag M., Mittelmeier T., Moroney J. V., Moseley J., Napoli C., Nedelcu A. M., Niyogi K., Novoselov S. V., Paulsen I. T., Pazour G., Purton S., Ral J. P., Riano-Pachon D. M., Riekhof W., Rymarquis L., Schroda M., Stern D., Umen J., Willows R., Wilson N., Zimmer S. L., Allmer J., Balk J., Bisova K., Chen C. J., Elias M., Gendler K., Hauser C., Lamb M. R., Ledford H., Long J. C., Minagawa J., Page M. D., Pan J., Pootakham W., Roje S., Rose A., Stahlberg E., Terauchi A. M., Yang P., Ball S., Bowler C., Dieckmann C. L., Gladyshev V. N., Green P., Jorgensen R., Mayfield S., Mueller-Roeber B., Rajamani S., Sayre R. T., Brokstein P., Dubchak I., Goodstein D., Hornick L., Huang Y. W., Jhaveri J., Luo Y., Martinez D., Ngau W. C., Otillar B., Poliakov A., Porter A., Szajkowski L., Werner G., Zhou K., Grigoriev I. V., Rokhsar D. S., Grossman A. R. (2007) The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science 318, 245–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pattison R. J., Amtmann A. (2009) N-Glycan production in the endoplasmic reticulum of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 92–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schoberer J., Strasser R. (2011) Sub-compartmental organization of Golgi-resident N-glycan processing enzymes in plants. Mol. Plant 4, 220–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Burda P., Aebi M. (1999) The dolichol pathway of N-linked glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1426, 239–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lehle L., Strahl S., Tanner W. (2006) Protein glycosylation, conserved from yeast to man: a model organism helps elucidate congenital human diseases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45, 6802–6818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Farid A., Pabst M., Schoberer J., Altmann F., Glössl J., Strasser R. (2011) Arabidopsis thaliana α1,2-glucosyltransferase (ALG10) is required for efficient N-glycosylation and leaf growth. Plant J. 68, 314–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lommel M., Strahl S. (2009) Protein O-mannosylation: conserved from bacteria to humans. Glycobiology 19, 816–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goto M. (2007) Protein O-glycosylation in fungi: diverse structures and multiple functions. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 1415–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ten Hagen K. G., Fritz T. A., Tabak L. A. (2003) All in the family: the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology 13, 1R–16R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Akashi T., Kawasaki S., Shibaoka H. (1990) Stabilization of cortical microtubules by the cell wall in cultured tobacco cells: Effects of extensin on the cold-stability of cortical microtubules. Planta 182, 363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kivirikko K. I., Myllylä R., Pihlajaniemi T. (1989) Protein hydroxylation: prolyl 4-hydroxylase, an enzyme with four cosubstrates and a multifunctional subunit. FASEB J. 3, 1609–1617 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Walmsley A. R., Batten M. R., Lad U., Bulleid N. J. (1999) Intracellular retention of procollagen within the endoplasmic reticulum is mediated by prolyl 4-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14884–14892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ko M. K., Kay E. P. (2001) Subcellular localization of procollagen I and prolyl 4-hydroxylase in corneal endothelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 264, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]