Background: Podoplanin-Fc inhibits lymphangiogenesis, but also causes a bleeding disorder by binding to CLEC-2 expressed on platelets.

Results: Mutation of threonine 34 in mouse Pdpn-Fc reduces 30-fold the binding to CLEC-2 and does not hamper its anti-lymphangiogenic activity.

Conclusion: PdpnT34A-Fc is an active lymphangiogenesis inhibitor with a better tolerability.

Significance: Mutagenesis of Pdpn-Fc is a valid approach to improve this tool for anti-lymphangiogenic therapy.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Lymphangiogenesis, Mutagenesis, Platelet, Recombinant Protein Expression, CLEC-2, Podoplanin

Abstract

The lymphatic system plays an important role in cancer metastasis and inhibition of lymphangiogenesis could be valuable in fighting cancer dissemination. Podoplanin (Pdpn) is a small, transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on the surface of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC). During mouse development, binding of Pdpn to the C-type lectin-like receptor 2 (CLEC-2) on platelets is critical for the separation of the lymphatic and blood vascular systems. Competitive inhibition of Pdpn functions with a soluble form of the protein, Pdpn-Fc, leads to reduced lymphangiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. However, the transgenic overexpression of human Pdpn-Fc in mouse skin causes disseminated intravascular coagulation due to platelet activation via CLEC-2. In the present study, we produced and characterized a mutant form of mouse Pdpn-Fc, in which threonine 34, which is considered essential for CLEC-2 binding, was mutated to alanine (PdpnT34A-Fc). Indeed, PdpnT34A-Fc displayed a 30-fold reduced binding affinity for CLEC-2 compared with Pdpn-Fc. This also translated into fewer side effects due to platelet activation in vivo. Mice showed less prolonged bleeding time and fewer embolized vessels in the liver, when PdpnT34A-Fc was injected intravenously. However, PdpnT34A-Fc was still as active as wild-type Pdpn-Fc in inhibiting lymphangiogenesis in vitro and also inhibited lymphangiogenesis in vivo. These data suggest that the function of Pdpn in lymphangiogenesis does not depend on threonine 34 in the CLEC-2 binding domain and that PdpnT34A-Fc might be an improved inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis with fewer toxic side effects.

Introduction

The lymphatic vascular system has important physiological functions draining interstitial tissue fluid, transporting antigens and immune cells, and in the uptake of intestinal lipids. Moreover, the lymphatic system contributes to a number of pathological processes, such as cancer metastasis, inflammatory diseases, and transplant rejection. In pathological settings, the lymphatic system actively expands, a process called lymphangiogenesis. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis has recently been proposed as a therapeutic approach for cancer therapy, as it may block the spread of cancer cells to the draining lymph node and beyond (1–3). Several molecules have been described to be important in the development, morphogenesis, and maintenance of lymphatic vessels, but so far only the antibody targeting of one of these molecules, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3, entered clinical trials (4).

Podoplanin (Pdpn)2 is an extensively O-glycosylated type-1 transmembrane protein expressed by lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) (5), follicular reticular cells (6), kidney podocytes (7), and alveolar type-1 cells (8). Via its extracellular domain, Pdpn binds galectin-8 (9), CCL21 (10), and C-type lectin-like receptor 2 (CLEC-2) (11). CLEC-2 is a membrane-bound protein expressed by platelets (12), dendritic cells (13), and neutrophils (14). Binding of the snake venom rhodocytin or Pdpn to CLEC-2 on platelets triggers intracellular signaling via Syk-SLP76 that leads to platelet activation (15). The molecular interaction between Pdpn and CLEC-2 has been shown to be important in the development of the lymphatic system, as it is involved in the physical separation of the lymph sacs from the blood-filled cardinal vein (16, 17). Also, CLEC-2-positive dendritic cells interact with Pdpn-positive LEC and follicular reticular cells for their migration from the periphery to and through the lymph node where they present antigens to T-cells (18). Very recently, the interaction between CLEC-2-positive platelets and Pdpn-positive follicular reticular cells was reported to be involved in maintaining the integrity of high endothelial venules (19).

Given its expression on LEC but not on blood vascular endothelial cells and its pivotal role in the development of the lymphatic system, Pdpn has been considered a suitable target to inhibit lymphangiogenesis. A human Pdpn-Fc chimera has been shown to be an effective lymphangiogenesis inhibitor in vitro and in vivo (20). However, mice overexpressing Pdpn-Fc under control of the skin-specific keratin 14 promoter displayed a bleeding disorder, namely disseminated intravascular coagulation. Apparently, the Pdpn-Fc present in the serum of these mice interacted with endogenous CLEC-2 expressed by platelets and thereby caused disseminated intravascular coagulation (20).

Here, we aimed to generate a Pdpn-Fc that would actively inhibit lymphangiogenesis, but would lack platelet aggregation side effects, thereby improving its tolerability. To this end, we mutagenized threonine 34, which is located in the first platelet aggregation stimulating (PLAG) domain of Pdpn and has been reported to be crucial for CLEC-2 binding (21). We produced two different isoforms of mouse Pdpn-Fc chimera (wild-type mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc) and compared their CLEC-2 binding and lymphangiogenesis inhibiting activities in vitro and in vivo. We found that mPdpnT34A-Fc was an inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis that was better tolerated. Its ability to interfere with CLEC-2 was reduced 30-fold, but its anti-lymphangiogenic activity was no lower than of the wild-type molecule.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Mutagenesis, Production, and Purification of mPdpn-Fc Isoforms

The coding sequence of the mouse podoplanin ectodomain was amplified by PCR from mouse lymphatic endothelial cell cDNA (forward primer, 5′-ACCCAAGCTTATGTGGACCGTGCCAG-3′, reverse primer, 5′-CGGATCCCCATCTTTCTTATCTGTTGTC-3′) and cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) in-frame with the coding sequence of the Fc domain of human IgG1. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the following primers: forward, 5′-ATGAAGATGATATTGTGGCCCCAGGTACAGGAGAC-3′, reverse, 5′-GTCTCCTGTACCTGGGGCCACAATATCATCTTCAT-3′. The mutation was confirmed by sequencing. Proteins were produced in stably transfected CHO (Chinese hamster ovary cells) cells. From the polyclonal stably transfected population, the clones expressing the highest levels of Pdpn-Fc were selected using the FACS-based method described in Zuberbühler et al. (22) and the hamster anti-mouse Pdpn antibody (clone 8.1.1). Recombinant proteins used in this study were produced either from the polyclonal population or from selected clones. Purification was performed using Protein A columns (Bio-Rad) as previously described (9).

Glycosylation Analysis

Recombinant mPdpn-Fc, mPdpnT34A-Fc, or total lysate from immortalized mouse lymphatic endothelial cells were diluted in PBS containing protease inhibitors (Complete mini protease inhibitor mixture, Roche Applied Science). To test for the presence of O-glycans, samples were first de-sialylated with neuraminidase (0.16 milliunits/ng of recombinant protein or 0.25 milliunits/ng lysate protein, Roche Applied Science) for 2 h at 37 °C. Samples were then denatured in 0.5% SDS, 40 mm DTT (5 min, 95 °C). A 10-fold excess of Nonidet P-40 over SDS was added prior to O-glycosidase digestion (0.016 milliunits/ng of recombinant protein or 0.05 milliunits/ng of lysate protein overnight, 37 °C). To test for the presence of N-glycans, samples were denatured in 0.1% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol (10 min, 95 °C). Peptide N-glycosidase F (50 milliunits/ng of protein, Roche Applied Science) was added together with a 10-fold excess of Triton X-100 over SDS and digestion was performed overnight at 37 °C. Digested and mock-digested samples were reduced and denatured in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and resolved on a 4–12% gradient gel (NuPAGE, Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes and immunodetected with a hamster anti-mouse Pdpn antibody (clone 8.1.1) and a HRP-coupled secondary anti-hamster IgG antibody (Abcam).

CLEC-2 Binding Assays

CLEC-2 reporter cells (BWZ.36-CLEC-2/CDζ3) and dectin1 control reporter cells (BWZ.36-dectin1/CDζ3) were kindly provided by Prof. Gordon Brown (University of Aberdeen) and cultured as previously described (23, 24). CLEC-2 activation studies were performed as previously described (23, 25). Briefly, 24-well plates were pre-coated with a capturing rabbit anti-human IgG Fc antibody (50 μg/ml, Jackson ImmunoResearch), followed by incubation with mPdpn-Fc or mPdpnT34A-Fc (20 ng/ml). 3 × 105 reporter cells per well were added and incubated overnight. As a positive control of activation, reporter cells were cultured with 40 ng/ml of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and 1.5 μg/ml of ionomycin. IL-2 released into the supernatant was quantified by ELISA (BD Pharmingen), and the cells were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase as previously described (23). For CLEC-2 binding studies, reporter cells were first incubated with an FcR blocking antibody (anti-CD16/32, Biolegend) for 30 min and then with 20 ng/ml of mPdpn-Fc isoforms or VEFR3-Fc (R&D Systems) for 1 h at 4 °C. After incubation with a secondary anti-human IgG Fc-specific antibody coupled with FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch), samples were analyzed for specific binding in a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (BD FACS Canto). Median fluorescence intensity for FITC was analyzed using FlowJo software. For competition assays and IC50 calculation, 100 μg of wild-type mPdpn-Fc was radiolabeled with 125I (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) using the IODO-GEN method and purified on a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) as previously described (26). CLEC-2 reporter cells (1.2 × 105) were incubated with 75 ng (2 nm) of radiolabeled tracer and increasing concentrations of unlabeled competitor (mPdpn-Fc WT or mPdpnT34A-Fc) for 2 h at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice with PBS and cell bound radioactivity in counts per minute (cpm) was measured in a γ counter and the data were plotted in GraphPad Prism software. The data were fitted using the nonlinear regression and IC50 for the two competitors was calculated using GraphPad Prism.

In Vitro Assays with Lymphatic Endothelial Cells

Immortalized mouse lymphatic endothelial cells (imLEC) were provided by Prof. Cornelia Halin (ETH Zurich) and cultured as described (27). Adhesion assays were performed as previously described (28). Briefly, 96-well cell culture plates were coated with type I collagen (50 μg/ml), 6 × 104 calcein-labeled imLEC per well were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 0.5 μm mPdpn-Fc isoforms or human IgG control (Sigma). Fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Haptotaxis assays were performed using transwells (pore size 8 μm; Costar), which were coated with 50 μg/ml of type I collagen on the bottom side. ImLEC (105 per well) were allowed to migrate for 3 h at 37 °C with 0.5 μm mPdpn-Fc isoforms or human IgG added to both the upper and lower compartment. Three (migration) or 8 (adhesion) replicates were performed, and the statistical significance of the data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with a Dunnett post test.

In Vivo Cornea Lymphangiogenesis Assay

Inflammatory lymphangiogenesis was induced in the cornea of BALB/c mice by suture placement as described previously (29). All protocols were approved by the University of California at Berkeley, Animal Care and Use Committee, and animals were treated according to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Mice were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine (50, 10, and 1 mg/kg body weight, respectively) for each surgical procedure. Seventy micrograms of mPdpn-Fc isoforms or human IgG (Sigma) were injected into the subconjunctival space twice a week for 2 weeks after suture placement. Then, corneas were excised, lymphatic and blood vessels were visualized by immunofluorescent staining for LYVE-1 (Abcam) and CD31 (Santa Cruz). The samples were observed with an Axioplan 2 epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss) and photographed with an Axiocam digital camera system (Zeiss). Corneal blood and lymphatic vessels were analyzed using NIH ImageJ software, as described previously (29). Vascular structures stained as CD31+LYVE-1− were identified as blood vessels, whereas those stained as CD31+LYVE-1+ were defined as lymphatic vessels. The percentage scores of LG coverage areas were obtained by normalizing to control groups where the lymphatic coverage areas were defined as being 100%. The results are reported as mean ± S.E. and Mann-Whitney test was used for the determination of significance levels between different groups using Prism software (GraphPad). The differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Developmental Diaphragm Lymphangiogenesis Assay

Animal experiments were performed complying with the animal protocols approved by the local veterinary authorities (Kantonales Veterinäramt Zürich). Pregnant mice (C57Bl6/J, Charles River) were injected intraperitoneally at 16.5 and 18.5 days postcoitum, corresponding to embryonic day (E) 16.5 and 18.5, with mPdpnT34A-Fc or hIgG control (100 μg/dose). Pups (6–7 per litter) were analyzed at postnatal day 5. The diaphragm was dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, and incubated in blocking solution (5% normal donkey serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05% sodium azide). Primary antibody against LYVE-1 (AngioBio) was incubated overnight in blocking solution. After extensive washes in PBS, samples were incubated with Alexa-coupled secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Diaphragms were flat mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Two diaphragmatic branches per mouse where imaged, using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710-FCS) equipped with a 10 × 0.3 NA EC Plan-Neofluar objective. The total LYVE-1 positive area, number of branches, and branch length were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Bleeding Time Measurement, Blood and Tissue Analysis

Ten- to 12-week-old female FVB mice were injected intravenously (tail vein) with 1 μg of mPdpn-Fc isoforms or human IgG control (Sigma). Six hours after injection, mice were deeply anesthetized and 5 mm of the tip of the tail were cut with a scalpel blade. Bleeding time was monitored by placing the cut tail into warm PBS. At the time of bleeding cessation, or after 60 min, mice were sacrificed and serum was collected for analysis. After withdrawing blood by cardiac puncture and body perfusion with PBS, livers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C and subsequently impregnated in 30% sucrose for 48 h. Organs were then embedded in OCT. Five-μm cryosections were immunostained for red blood cells (RBC) (Ter119 antibody, eBioscience) or platelets (CD41, BD Biosciences). The RBC and platelet-stained area were analyzed in five ×10 or 20 magnified images per section using ImageJ software. Pdpn-Fc levels in serum samples were analyzed by capture ELISA. Briefly, maxisorp 96-well plates (NUNC) were coated with 100 ng/ml of rabbit anti-human Fc capturing antibody in PBS (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at 37 °C. After 1 h of blocking with 1% FCS in PBS, standards and diluted serum samples were added for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were washed three times with 0.05% Tween in PBS and then incubated with the hamster anti-mouse Pdpn (clone 8.11) antibody followed by an HRP-coupled anti-hamster IgG antibody. For detection, the BM blue POD substrate (Roche Applied Science) was used following the manufacturer's instructions. The standard curve was analyzed using a four-parameter logistic fit.

Ex Vivo FACS Analysis of Platelet Activation

Blood was withdrawn from deeply anesthetized FVB wild-type female mice via cardiac puncture and mixed 1:10 with ACD anticoagulant (acid-citrate-dextrose, Sigma). Whole blood was diluted in modified Tyrode's buffer (137 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES, 2.7 mm KCl, 3.3 mm NaH2PO4, 5.6 mm glucose, 1 g/liter of BSA, 1 mm Mg2Cl, 1 mm Ca2Cl) plus 1 mm GPRP peptide (PEFA-block, Pentapharm) and incubated for 1 h with mPdpn-Fc isoforms (100 ng) in the presence of an anti human-Fc cross-linking antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or with thrombin (0.2 unit, Sigma) as a positive control of activation. Activated blood was stained with the following antibodies: anti-CD41-APC (Biolegend), anti-activated integrin αIIbβ3-PE (clone JON/A, Emfret Analytics), and anti-CD62p-FITC (clone Wug.E9, Emfret Analytics). Samples were acquired with a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS Canto, BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software.

RESULTS

Characterization of Two Recombinant Mouse Podoplanin-Fc Isoforms, mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc

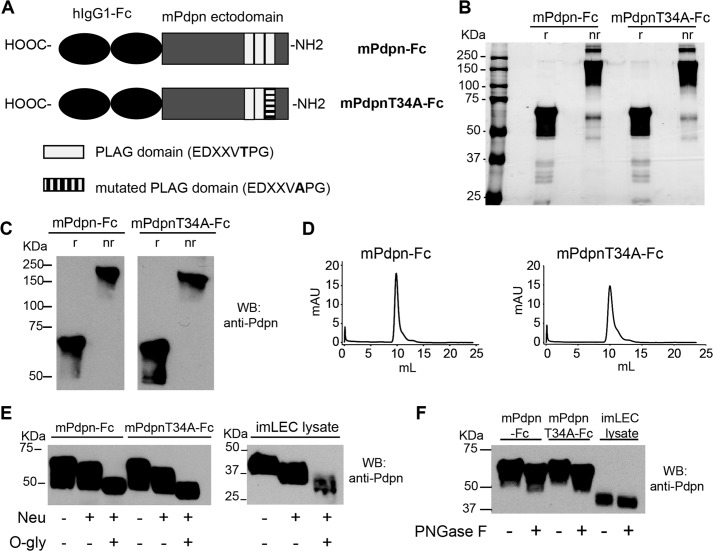

We previously reported that human podoplanin-Fc acts as a lymphangiogenesis inhibitor in vitro and in vivo (20). However, its transgenic overexpression in mouse skin causes disseminated intravascular coagulation due to its capacity to activate platelets and induce platelet aggregation via CLEC-2. To circumvent this side effect, we cloned a mouse Pdpn-Fc chimera and mutagenized threonine 34 to alanine (T34A), attaining the mPdpnT34A-Fc isoform (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of two recombinant mouse podoplanin Fc chimera isoforms, mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc. A, schematic representation of mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc. B, recombinant mPdpn-Fc isoforms were produced in CHO cells, affinity purified using Protein A and samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing (r) or non-reducing (nr) conditions. Silver staining revealed that both proteins were >95% pure. C, both isoforms were stained by an antibody directed against mouse podoplanin in Western blot and were present as disulfide-linked dimers. D, purified proteins were analyzed by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/30 column. They eluted as single species. E, to characterize their glycosylation, purified mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc as well as the cell lysate of mouse immortalized LEC (imLEC) were digested with neuraminidase (Neu) followed by O-glycosidase (O-gly). F, to test for the presence of N-glycans, digestion was performed with peptide N-glycanase F (PNGase F). Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an anti-mouse Pdpn antibody (E and F). Both isoforms were sialylated and decorated with core-1 O-glycans. Moreover, the extent of sialylation and O-glycosylation was comparable with one of the endogenous podoplanin expressed by imLEC. The recombinant proteins and endogenous Pdpn appeared to also be N-glycosylated.

Both recombinant proteins were expressed in CHO cells and purified by protein A affinity chromatography. Analysis by SDS-PAGE and silver staining, immunoblot, and gel filtration chromatography revealed that the recombinant proteins were pure, immunoreactive for Pdpn, and dimeric with the monomers linked through disulfide bridges (Fig. 1, B–D). Digestion with neuraminidase followed by O-glycosidase (Fig. 1E) showed that both recombinant proteins were sialylated and O-glycosylated. Based on the narrow specificity of O-glycosidase, which only cleaves desialylated core-1 O-glycans, this observation points to the presence of core-1 O-glycans. Glycosylation of the two recombinant murine Pdpn-Fc isoforms appeared comparable with the glycosylation of Pdpn expressed by immortalized mouse LEC with regard to both glycan types and abundance. Digestion with peptide N-glycosidase F revealed that the recombinant proteins as well as the endogenous LEC Pdpn were also N-glycosylated (Fig. 1F).

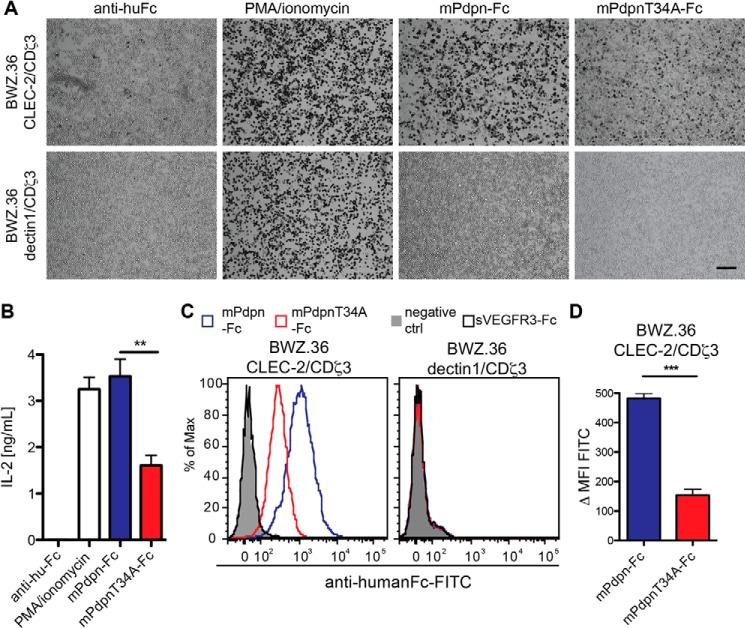

mPdpnT34A-Fc Showed a Reduced Ability to Activate and Bind to CLEC-2 Reporter Cells

To test the CLEC-2 binding and activation ability of the two mPdpn-Fc isoforms, we utilized CLEC-2 reporter cells (BWZ.36 CLEC-2/CDζ3) and dectin1 reporter cells (BWZ.36 dectin1/CDζ3) expressing a control C-type lectin receptor (24). This cellular reporter system is based on BWZ.36 cells as described by others (30). Briefly, BWZ.36 cells were transduced to express a chimeric CLEC-2/CDζ3 receptor, or a control dectin1/CDζ3 chimeric receptor. Ligand binding to CLEC-2 or dectin1 induces signaling through the CDζ3 cytoplasmic tail, and the expression of β-galactosidase and IL-2. We found that mPdpn-Fc potently activated CLEC-2 reporter cells as shown by both X-gal staining (Fig. 2A) and IL-2 secretion into the supernatant (Fig. 2B). However, CLEC-2 activation by mPdpnT34A-Fc was significantly reduced as evidenced by weaker X-gal staining and lower IL-2 secretion. The binding of both mPdpn-Fc isoforms was specific to CLEC-2, because no activation was observed in dectin1 control reporter cells. Binding to CLEC-2 was also assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). Also in this setting, mPdpn-Fc specifically bound to CLEC-2 on the surface of the reporter cells. mPdpnT34A-Fc displayed a significantly reduced ability to bind the receptor, as quantified by Δ median fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI, Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

mPdpnT34A-Fc showed a reduced ability to bind to and activate CLEC-2 reporter cells. BWZ.36 CLEC-2/CDζ3 and dectin1/CDζ3 reporter cells were used. Binding of a specific ligand to the C-type lectin-like receptors (CLEC-2 or dectin1) results in β-galactosidase expression and IL-2 production. A, CLEC-2 and dectin1 reporter cells were added to the mPdpn-Fc isoforms (20 ng/ml) immobilized through a human Fc capturing antibody or to the human Fc capturing antibody only. Reporter cells cultured with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-ionomycin served as a positive control of cell activation. Pictures were taken with an inverted microscope (×5 magnification). Scale bar, 200 μm. The number of X-gal-stained, activated CLEC-2 reporter cells was much lower on mPdpnT34A-Fc-coated than on mPdpn-Fc-coated plates. None of the immobilized proteins activated dectin1-expressing cells. B, IL-2 secreted by activated CLEC-2 reporter cells was measured by ELISA. Significantly less IL-2 was produced by the CLEC-2 reporter cells bound to mPdpnT34A-Fc as compared with mPdpn-Fc. C, CLEC-2 or dectin1-expressing cells were incubated with mPdpn-Fc isoforms, soluble VEGFR3-Fc (20 ng/ml), or buffer only (negative control). After incubation with a FITC-labeled, anti-human Fc antibody, binding was assessed by flow cytometry. D, Δ median fluorescent intensity (ΔMFI) was analyzed with FlowJo software. mPdpnT34A-Fc was found to bind less well to the CLEC-2-expressing cells compared with mPdpn-Fc. This binding was specific, as no binding was observed to the dectin1-expressing cells. Data represent mean ± S.E., statistical significance was analyzed using the unpaired Student's t test, **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.0001.

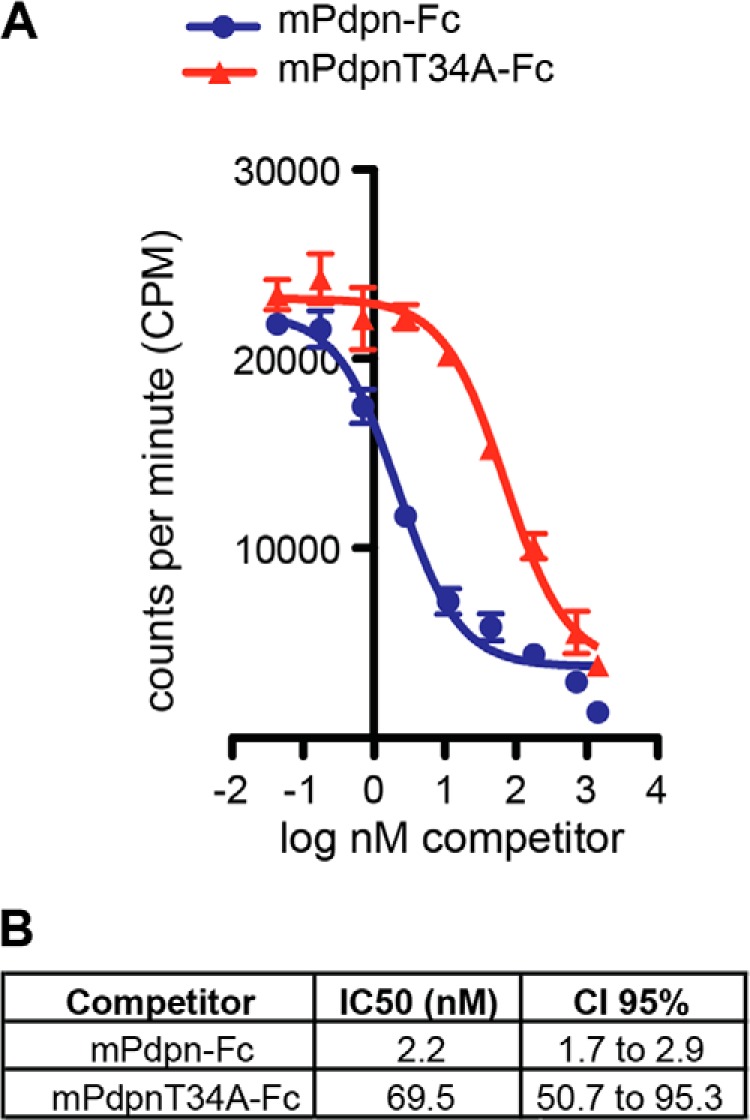

IC50 of mPdpnT34A-Fc for CLEC-2 Was Reduced 30-Fold Compared with mPdpn-Fc

To study the interaction between mPdpn-Fc isoforms and CLEC-2 quantitatively, we radiolabeled mPdpn-Fc with iodine 125 and performed competitive binding measurements on CLEC-2 expressing cells with increasing doses of unlabeled mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, mPdpn-Fc bound to CLEC-2 with an IC50 of 2.2 nm (confidence interval 95%, 1.7 to 2.9 nm). The affinity of mPdpnT34A-Fc was 30 times lower, with an IC50 of 69.5 nm (confidence interval 95%, 50.7 to 95.3 nm). Taken together, these data indicate that the T34A mutation does not completely abolish the ability of Pdpn to bind to CLEC-2.

FIGURE 3.

IC50 of mPdpnT34A-Fc for CLEC-2 is reduced 30-fold compared with mPdpn-Fc. A, mPdpn-Fc WT was radiolabeled with iodine 125 and incubated with CLEC-2 reporter cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled mPdpn-Fc or mPdpnT34A-Fc (competitor). B, IC50 was calculated with GraphPad Prism. Even though both mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc display an IC50 in the low nanomolar range, the IC50 of mPdpnT34A-Fc is 30 times lower. CI, confidence interval.

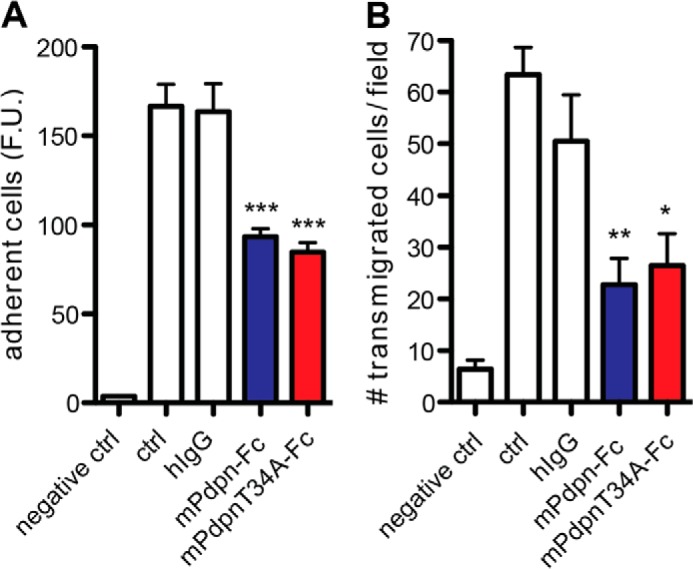

mPdpnT34A-Fc Retained Full Ability to Inhibit Lymphangiogenesis in Vitro and in Vivo

Human Pdpn-Fc was shown to be a lymphangiogenesis inhibitor (20). Here, we compared the anti-lymphangiogenic activity of mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc using two in vitro assays that mimic crucial steps in the formation of new lymphatic vessels, namely the ability of LEC to adhere and to migrate in the extracellular matrix. Both proteins were tested in vitro using imLEC and found to significantly inhibit LEC adhesion to collagen type I (Fig. 4A) and LEC migration toward collagen type I (Fig. 4B). In both assays, no significant difference was observed between the two Pdpn-Fc isoforms. Threonine 34 appears therefore not to be essential for the anti-lymphangiogenic activity of mPdpn-Fc in vitro.

FIGURE 4.

mPdpnT34A-Fc retains full ability to inhibit lymphangiogenesis in vitro. A, calcein-labeled imLEC were allowed to adhere to collagen type I for 20 min in the presence of 0.5 μm mPdpn-Fc, mPdpnT34A-Fc, or hIgG control. After washing, adherent cells were quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity in a microplate fluorescence reader. mPdPn-Fc and PdpnT34A-Fc inhibited LEC adhesion to a similar, significant degree. B, Transwells were coated with collagen type I and imLEC were allowed to migrate toward immobilized collagen for 3 h in the presence of 0.5 μm mPdpn-Fc, mPdpnT34A-Fc, or hIgG control. Migrated cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. Five images were taken per transwell (×5 magnification) and the number of migrated cells per field was quantified using ImageJ software. mPdpn-Fc and mPdpnT34A-Fc inhibited LEC migration to a similar, significant degree. Data represent mean ± S.E., statistical significance was analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance and a Dunnett post test, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.0001.

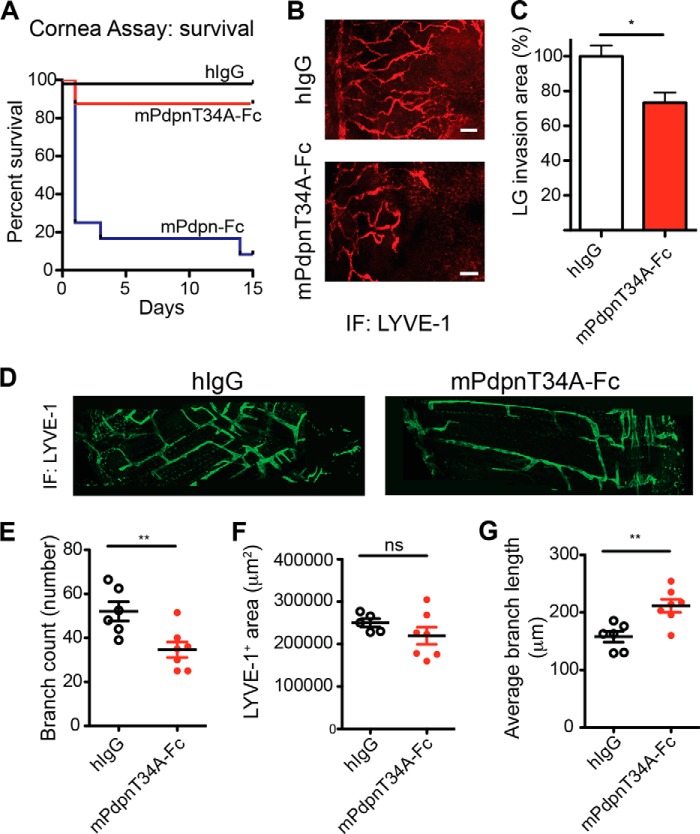

We then investigated the anti-lymphangiogenic activity of mPdpn-Fc isoforms in two in vivo models of lymphangiogenesis that better represent the complexity of the whole lymphangiogenic process. In the first model, three sutures were placed into the mouse cornea, which is normally devoid of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The sutures serve as an inflammatory stimulus to trigger the growth of both blood and lymphatic vessels. After suture placement, mice received mPdpn-Fc, mPdpnT34A-Fc, or human IgG control by subconjunctival injection twice a week for 2 weeks. Surprisingly, 80% of the mice treated with mPdpn-Fc died after the first injection (Fig. 5A), displaying signs of pulmonary embolism (difficulties in breathing and recovering from anesthesia). After 2 weeks, the remaining mice in the mPdpnT34A-Fc and human IgG groups were sacrificed and their corneas stained for the lymphatic marker LYVE-1 (Fig. 5B). The area covered by invaded lymphatic vessels was quantified. Mice treated with mPdpnT34A-Fc had a significantly smaller lymphatic vessel invasion area in the cornea, compared with human IgG control (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the treatments did not influence blood vessel invasion (not shown). mPdpnT34A-Fc is therefore an active lymphangiogenesis inhibitor in vivo, which does not provoke pulmonary embolisms and thus lacks the potent toxic effect of mPdpn-Fc. In a second in vivo model of lymphangiogenesis, we took advantage of the fact that the lymphatic network in the mouse diaphragm develops during embryogenesis and the early postnatal days. Mouse embryos where treated at E16.5 and E18.5 with either mPdpnT34A-Fc or hIgG control, which were injected intraperitoneally into the pregnant mother. At this point in development, the lymphatic system was already separated from the cardinal vein, and the lymphatic plexuses are expanding in peripheral organs. Pups where analyzed at postnatal day 5. The mPdpnT34A-Fc was detected in the serum of the pups by ELISA (data not shown), indicating that the recombinant protein was transported through the placenta. The lymphatic network in the diaphragm of the mPdpnT34A-Fc-treated pups appeared less complex than that of the control treated animals when whole mount preparations were stained for LYVE-1 (Fig. 5D). Morphometric analyses revealed a reduced number of branches (Fig. 5E) and a higher average branch length (Fig. 5G) despite a comparable total LYVE-1 positive area (Fig. 5F). This suggests that upon mPdpnT34A-Fc treatment, a less complex lymphatic network develops, characterized by fewer and longer branches. Taken together, the present data show that mPdpnT34A-Fc inhibits inflammatory as well as developmental lymphangiogenesis in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

mPdpnT34A-Fc retains full ability to inhibit lymphangiogenesis in vivo. A, three sutures were placed on the corneas of BALB/c mice and 70 μg of mPdpn-Fc (n = 12), mPdpnT34A-Fc (n = 8), or IgG control (n = 8) were injected into the subconjunctival space twice weekly for 2 weeks. Survival of the animals in the different treatment groups is shown by a Kaplan-Mayer curve. Although animals injected with mPdpnT34A-Fc or hIgG survived, 80% of animals treated with mPdpn-Fc died after the first or second injection. B and C, lymphatic vessel invasion into the cornea was quantified by staining for the lymphatic-specific marker LYVE-1 and was found to be significantly lower in mPdpnT34A-Fc-treated animals compared with human IgG control. D, diaphragms of 5-day-old mice treated in utero at E16.5 and 18.5 wher stained for LYVE-1. mPdpnT34A-Fc-treated mice had a less complex diaphragmatic lymphatic network. E–G, confocal images of diaphragmatic branches were morphometrically analyzed for the parameters branch number, LYVE-1-stained area, and average branch length. The mPdpnT34A-Fc-treated mice had a less complex lymphatic network characterized by less but longer branches. Data represent mean ± S.E., statistical significance was analyzed using the unpaired Student's t test, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

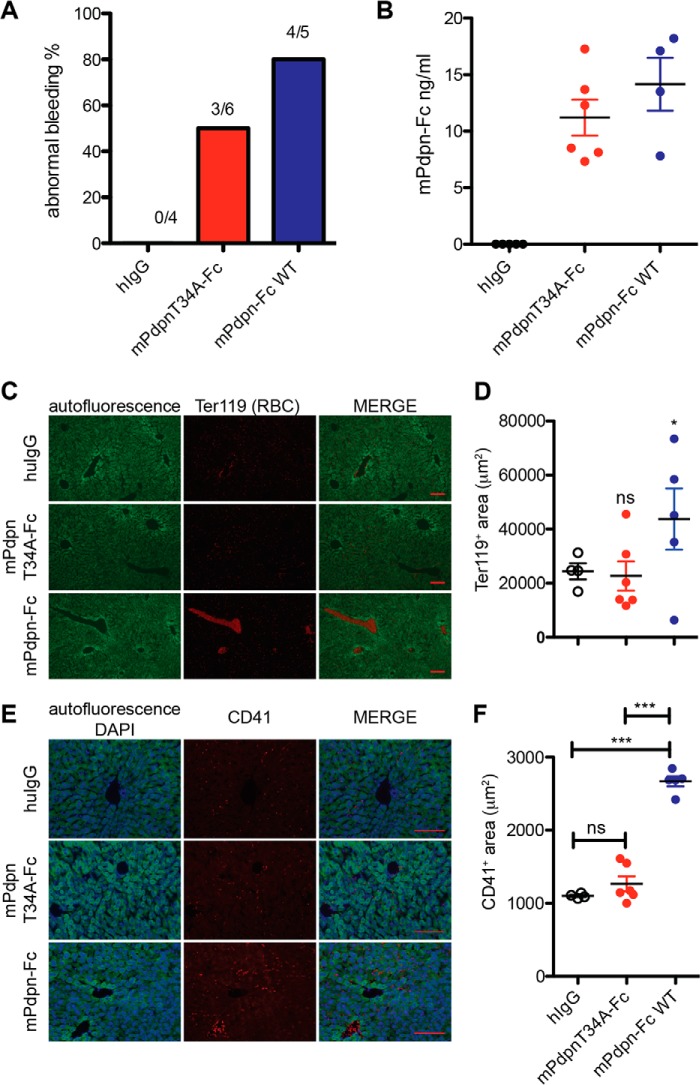

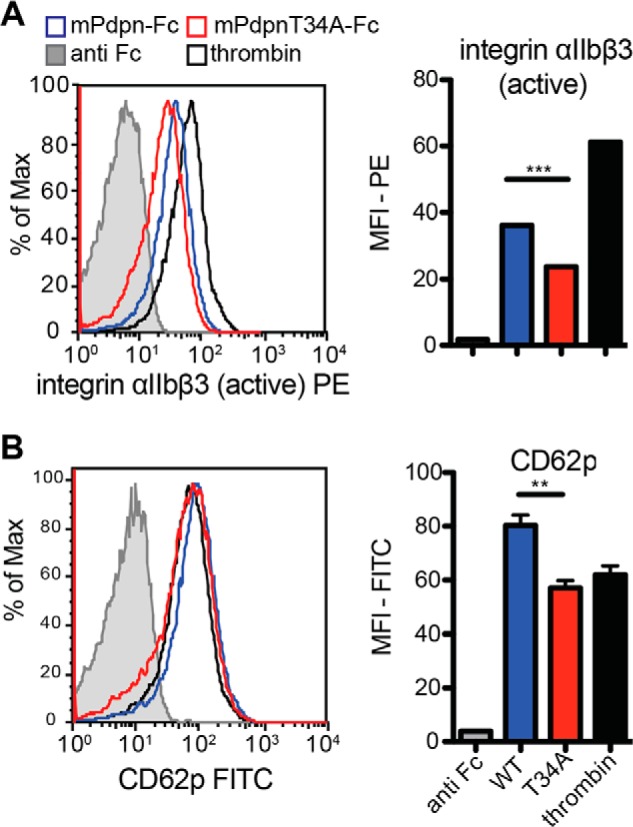

mPdpnT34A-Fc Displayed Reduced Toxicity and Reduced Ability to Induce Platelet Aggregation in Vivo

We next evaluated the toxic effect of mPdpn-Fc on mice more closely. Mice were injected intravenously with mPdpn-Fc, mPdpnT34A-Fc, or human IgG control. Six hours afterward, bleeding time was measured by tail clipping. 80% of the mice that had received mPdpn-Fc did not stop bleeding after 60 min (Fig. 6A). In those mice, we observed embolized vessels in the liver as assessed by immunostaining for red blood cells (RBC) (Fig. 6, C and D) and for platelets (CD41, Fig. 6, E and F). Conversely, only half of the mice that had received mPdpnT34A-Fc displayed prolonged bleeding times. The area covered by the embolized vessels and the extent of platelet deposition in their livers was comparable with control treated animals (Fig. 6, D and F). The levels of circulating mPdpn-Fc isoforms in serum were comparable among all mice as measured by ELISA (Fig. 6B). In particular, they were similar between the treatment groups and there was no correlation between serum concentration and bleeding time (not shown). To test a direct effect of mPdpn-Fc isoforms on platelet activation, we incubated mouse whole blood with recombinant proteins in the presence of a cross-linking anti-human Fc antibody, and analyzed the levels of the activation markers integrin αIIbβ3 (active form, Fig. 7A) and CD62p on platelets by FACS (Fig. 7B). The mPdpnT34A-Fc had a significantly reduced ability to induce both activation markers and therefore to activate platelets ex vivo. Collectively, our data suggest that mPdpnT34A-Fc induced less platelet activation, therefore provoked fewer embolized liver vessels and fewer bleeding abnormalities in mice making it a significantly less toxic agent than mPdpn-Fc.

FIGURE 6.

mPdpnT34A-Fc displays reduced toxicity and a reduced ability to induce platelet aggregation in vivo. A, FVB mice received either 1 μg of mPdpn-Fc isoforms or hIgG control by tail vein injection. Six hours later, the tail was clipped and bleeding time was measured. Only 50% of the mice treated with mPdpnT34A-Fc displayed abnormal bleeding (>60 min), whereas 80% of the mice that received mPdpn-Fc bled abnormally. B, serum levels of circulating mPdpnFc isoforms at 6 h after injection of 1 μg of protein were assessed by capture ELISA and found to be comparable between the two groups. C, frozen sections of livers were stained for red blood cells (RBC) to visualize embolized vessels. The autofluorescence of the liver is shown in green fluorescence channel. D, the RBC-positive area was quantified with ImageJ. The area covered by RBC-positive blood clots was significantly lower in the livers of mice treated with mPdpnT34A-Fc than in mice treated with mPdpn-Fc. E, frozen sections of livers were stained for platelets (CD41) to visualize platelet deposition. The autofluorescence of the liver is shown in the green fluorescence channel and DAPI was used to visualize the nuclei. F, the CD41 positive area was quantified with ImageJ. The area covered by CD41-positive platelets was significantly lower in the livers of mice treated with mPdpnT34A-Fc than in mice treated with mPdpn-Fc. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data represent mean ± S.E.; statistical significance was analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance and a Dunnett post test. ***, p < 0.001.

FIGURE 7.

mPdpnT34A-Fc displays reduced ability to induce platelet activation ex vivo. A, whole blood was incubated with mPdpn-Fc isoforms in the presence of a cross-linking anti-Fc antibody. Anti-Fc antibody alone and thrombin served as negative and positive controls, respectively. CD41-positive platelets were gated and analyzed for the expression of activated integrin αIIbβ3 (A) and CD62p (B), markers of platelet activation and degranulation, respectively. Median fluorescence intensity was calculated with FlowJo. mPdpnT34A-Fc had a reduced ability to activate platelets ex vivo. Data represent mean ± S.E.; statistical significance was analyzed using the unpaired Student's t test, **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Lymphatic vessels play critical roles in the physiologic maintenance of fluid homeostasis. However, formation of new lymphatic vessels may contribute to pathological conditions, for instance, by favoring cancer spread and metastasis. Under such circumstances, inhibition of lymphangiogenesis may be clinically valuable. Pdpn, a mucin-type glycoprotein typically expressed on lymphatic endothelial cells and a major player in lymphatic development, has been proposed as a suitable target for modulation of lymphangiogenesis. Blocking Pdpn by means of a soluble form of its ectodomain, the Pdpn-Fc chimera, lead to inhibition of lymphangiogenesis. However, its overexpression in mouse skin provoked disseminated intravascular coagulation due to the interaction of Pdpn-Fc with CLEC-2 expressed on platelets (20).

Here, we aimed at generating an improved mouse Pdpn-Fc chimera that would lack CLEC-2 related toxicity while retaining anti-lymphangiogenic activity by mutagenizing threonine 34, a residue reported to be crucial for CLEC-2 binding (21). We produced and purified two mPdpn-Fc isoforms using CHO cells and protein A affinity chromatography. With regard to the types of glycans present, the two mPdpn-Fc chimera appeared comparable with endogenous Pdpn expressed by mouse LEC. Neuraminidase and O-glycanase digests revealed the presence of large amounts of sialylated core-1 O-glycans. Both mPdpn-Fc isoforms as well as the natural Pdpn of mouse LECs appeared to additionally carry some N-glycan as evidenced by peptide N-glycosidase F digestion. There is one potential site of N-glycosylation in the ectodomain of mouse Pdpn, and another in the human Fc domain of the recombinant proteins. In a previous analysis, Scholl et al. (31) assessed the O- and N-glycosylation profiles of Pdpn derived from a mouse carcinoma cell line (PDV) and did not detect any N-linked glycans. This difference in findings may either be due to the small impact of single N-glycans on apparent molecular weight or point to a cell-specific difference in N-glycosylation of Pdpn. It is possible that a differential glycosylation might play a role in the regulation of the multiple, cell-specific functions of this versatile molecule.

Pdpn binds CLEC-2 via its extracellular domain and this interaction mediates platelet aggregation and dendritic cell migration (32). Kato and colleagues (21) identified a conserved octapeptide sequence within the Pdpn ectodomain, which they called PLAG domain as it appeared to be crucial for the platelet aggregation-inducing effect of Pdpn. Namely, they showed that CHO cells expressing a mutated form of mouse Pdpn in which threonine 34 within the first PLAG domain was replaced by alanine (PdpnT34A) failed to induce platelet aggregation in platelet-rich plasma. Based on these findings, we mutagenized threonine 34 of mouse Pdpn-Fc to alanine in an attempt to improve its tolerability. Surprisingly, we only observed a reduction in binding to CLEC-2 reporter cells, but not a complete abolishment in three different binding assays. The reduced binding corresponded to a 30-fold reduction of the IC50 when measured by a competitive binding assay using [125I]Pdpn-Fc. The reduction appeared somewhat smaller in the FACS-based binding assay (Fig. 2D) and in the assay measuring IL-2 secretion induced upon engagement of CLEC-2 by mPdpn-Fc (Fig. 2B). However, the competitive radiolabeled assay was performed titrating the dose of inhibitors, whereas the other assays tested binders at a single dose. The competitive binding assay is thus the only assay that has the power to measure quantitatively a difference in binding that was already observed in the other two assays performed. Collectively, our data suggest that elimination of threonine 34 and possibly an O-glycan, which may be attached to it, is not sufficient to abolish binding to CLEC-2 as previously described by Kato et al. (21). However, our experimental setting clearly differed from the one chosen by Kato and colleagues (21). We used soluble Pdpn-Fc chimera interacting with CLEC-2 expressed on the cell membrane of reporter cells, whereas Kato et al. (21) used Pdpn mutants expressed at the surface of CHO cells interacting with platelet-rich plasma. We measured binding, whereas Kato et al. (21) measured platelet activation. However, it appears that threonine 34 and/or a potential threonine 34-bound O-glycan contribute to CLEC-2 binding. It can thus be speculated that the CLEC-2 binding domain of Pdpn may be larger, comprising additional parts of the protein and/or other glycans. Such a binding domain comprising not only a threonine-linked O-glycan but also several residues of the underlying protein has been reported for the C-type lectin P-selectin (33). Its binding site on P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 comprises, in addition to the sialylated and fucosylated core-2 O-glycan linked to threonine 47, three sulfated tyrosine residues (Tyr-46, Tyr-48, and Tyr-51) and several negatively charged amino acids. Whereas both the glycan and the underlying peptide are essential for binding, the three tyrosine sulfates contribute to binding, increasing the affinity 30-fold (33). Alternatively, there may be additional CLEC-2 binding sites on Pdpn. For instance, the ectodomain of Pdpn comprises not only one PLAG domain, but three tandem repeats, and the role of PLAG-2 and PLAG-3 has not been fully elucidated (34). Moreover, there are also reports indicating that the C-terminal region of Pdpn is necessary for its strong interaction with CLEC-2 (35). Some C terminally truncated mutants of the extracellular part of Pdpn fused to Fc failed to bind CLEC-2 despite intact PLAG domains (35). We therefore conclude that other residues besides threonine 34 and other parts of the protein may also be involved in the interaction between Pdpn and CLEC-2.

Independently of the presence or absence of threonine 34 and/or the O-glycan it may carry, Pdpn-Fc potently inhibited lymphangiogenesis when tested in functional LEC assays. Indeed, both Pdpn-Fc and PdpnT34A-Fc similarly and significantly inhibited adhesion and migration of LEC to collagen type I in vitro. Both Pdpn-Fc isoforms presumably act by interfering with the function of endogenous Pdpn expressed on LEC, blocking its interaction with an as yet unknown ligand. Knock-down of Pdpn on LEC has been shown to inhibit LEC adhesion to collagen type I, whereas up-regulation of Pdpn in EOMA cells stimulated their migration toward collagen and fibronectin (36). Collectively, these data suggest a role for Pdpn in LEC adhesion and migration, two key processes in the formation of new lymphatic vessels from pre-existing vessels. Also in other cell types, such as transformed keratinocytes, Pdpn was shown to be involved in cell migration by interacting with the cytoskeleton linkers ezrin and moesin, modulating actin reorganization, and inducing epithelial to mesenchymal transition (31, 37). Our present data support a CLEC-2 independent anti-lymphangiogenic action of Pdpn-Fc. The interaction between Pdpn and CLEC-2 has been shown to be important in ontogeny, when the lymphatic system buds and then separates from the cardinal vein (16), and at the lymphovenous valve throughout life, where platelets are important to maintain blood-lymphatic separation also in adult animals (38). So it appears that CLEC-2-dependent functions of Pdpn are involved wherever there is a connection between blood and lymphatic vessels. It was reported that platelets might inhibit LEC function (39, 40). Whether this is a direct effect via Pdpn-mediated changes in LECs, or an indirect effect due to a soluble factor (i.e. BMP-9) released by activated platelets, still remains unclear. However, to the best of our knowledge, binding of Pdpn-expressing lymphatic vessels to CLEC-2 expressing cells has never been reported in pathological lymphangiogenesis. Therefore, CLEC-2 seems not to be involved in pathological lymphangiogenesis and mPdpn-Fc appears to inhibit lymphangiogenesis independently of CLEC-2.

In vivo, PdpnT34A-Fc injected at a dose of 70 μg into the subconjunctival space efficiently inhibited the growth of lymphatic vessels in a model of inflammatory lymphangiogenesis in the cornea. At a dose of 100 μg injected intraperitoneally into pregnant mice, it inhibited branching of lymphatic vessels in the diaphragm of newborn mice. A comparison to the anti-lymphangiogenic activity of the wild-type form suggested by the in vitro experiments turned out to be impossible, as Pdpn-Fc proved to be extremely toxic, with 80% of mice that had received subconjunctival injections of this isoform dying and showing signs of pulmonary embolism. We previously reported that mice treated with human Pdpn-Fc had a reduced lymphangiogenic response in the cornea model, but we did not observe any severe toxicity (20). In the present study, instead of human Pdpn-Fc we utilized a mouse Pdpn-Fc chimera. The amino acid sequence identity between human and mouse Pdpn ectodomain is only 48%. It is therefore possible that the toxic effects are more apparent when mouse Pdpn-Fc is administered in the same species. This observation further supports the contribution of less conserved Pdpn residues in platelet binding together with conserved residues of the PLAG domains. In line with these observations, 80% of mice that received Pdpn-Fc intravenously showed prolonged bleeding time, embolized vessels, and platelet aggregation in the liver. In contrast, mPdpnT34A-Fc was better tolerated. Only 50% of the mice that received mPdpnT34A-Fc intravenously showed prolonged bleeding time and the extent of embolized vessels and platelet aggregation in the liver was as low as in control treated animals. Of note is that we observed only a reduction in toxicity, but not a complete abolishment. This is in accordance with the results of our competitive binding assay that only showed a 30-fold reduced binding of PdpnT34A-Fc to CLEC-2 compared with the wild-type isoform. It is also in agreement with mPdpnT34A-Fc leading to some activation of platelets in vitro, as measured by FACS analysis of platelet activation markers, namely the active form of integrin αIIbβ3 and CD62p, even though this activation was significantly lower than the one induced by wild-type mPdpn-Fc. These data further demonstrate that the reduced toxicity of mPdpnT34A-Fc in vivo is a result of its reduced ability to bind CLEC-2 and trigger platelet activation. Taken together, our data indicate that mutation of threonine 34 and the removal of the potentially attached O-glycan does not hamper the anti-lymphangiogenic activity of Pdpn-Fc, suggesting that the function of Pdpn in lymphangiogenesis does not depend on this residue. By reducing the interaction between Pdpn and CLEC-2 30-fold, however, mutation of threonine 34 improves its tolerability. As the toxicity related to CLEC-2 binding and platelet activation could not be fully abolished, it would be of interest to explore additional measures to further reduce toxicity. Previous studies of human Pdpn revealed that a short version of the molecule, comprising only the 2nd and 3rd PLAG domains and carrying a disialyl core-1 O-glycan, did bind CLEC-2 but did not induce platelet aggregation. Indeed, only a full-length, 128-amino acid version of human podoplanin efficiently induced platelet aggregation (35). Furthermore, a non-glycosylated version of human Pdpn-Fc retained the ability to inhibit lymphangiogenesis in vitro (20), but non-sialylated human Pdpn did not induce platelet aggregation (41). Therefore, C terminally shortened and non-glycosylated versions of mouse Pdpn-Fc should be tested in future studies for their anti-lymphangiogenic and platelet activating properties. Such studies will be of great importance to further improve our understanding of the role of other amino acids, other parts, and the glycosylation of mouse Pdpn for CLEC-2 binding and inhibition of lymphangiogenesis. They may also pave the way for further improvement of this molecule as an agent for anti-lymphangiogenic therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Gordon Brown for providing CLEC-2 and dectin1 reporter cells, Prof. Cornelia Halin, Prof. Sabine Werner, Prof. Dontscho Kerjaschki, and Prof. Roger Schibli for helpful discussions, Susan Cohrs for precious technical assistance, Dr. Oliver Speer and Dr. Lothar Dieterich for advice on the platelet assay, and Thomas List for help with gel filtration chromatography.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health, Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 31003A-130627, European Research Council Grant LYVICAM, Oncosuisse, Krebsliga Zurich, and the Leducq Foundation.

- Pdpn

- podoplanin

- LEC

- lymphatic endothelial cells

- CLEC-2

- C-type lectin-like receptor 2

- imLEC

- mouse immortalized LEC

- PLAG

- platelets aggregation stimulating domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cueni L. N., Detmar M. (2008) The lymphatic system in health and disease. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 6, 109–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alitalo K. (2011) The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat. Med. 17, 1371–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tammela T., Alitalo K. (2010) Lymphangiogenesis: molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell 140, 460–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alitalo A., Detmar M. (2012) Interaction of tumor cells and lymphatic vessels in cancer progression. Oncogene 31, 4499–4508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breiteneder-Geleff S., Soleiman A., Kowalski H., Horvat R., Amann G., Kriehuber E., Diem K., Weninger W., Tschachler E., Alitalo K., Kerjaschki D. (1999) Angiosarcomas express mixed endothelial phenotypes of blood and lymphatic capillaries: podoplanin as a specific marker for lymphatic endothelium. Am. J. Pathol. 154, 385–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farr A. G., Berry M. L., Kim A., Nelson A. J., Welch M. P., Aruffo A. (1992) Characterization and cloning of a novel glycoprotein expressed by stromal cells in T-dependent areas of peripheral lymphoid tissues. J. Exp. Med. 176, 1477–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Breiteneder-Geleff S., Matsui K., Soleiman A., Meraner P., Poczewski H., Kalt R., Schaffner G., Kerjaschki D. (1997) Podoplanin, novel 43-kDa membrane protein of glomerular epithelial cells, is down-regulated in puromycin nephrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 151, 1141–1152 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams M. C., Cao Y., Hinds A., Rishi A. K., Wetterwald A. (1996) T1α protein is developmentally regulated and expressed by alveolar type I cells, choroid plexus, and ciliary epithelia of adult rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 14, 577–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cueni L. N., Detmar M. (2009) Galectin-8 interacts with podoplanin and modulates lymphatic endothelial cell functions. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1715–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kerjaschki D., Regele H. M., Moosberger I., Nagy-Bojarski K., Watschinger B., Soleiman A., Birner P., Krieger S., Hovorka A., Silberhumer G., Laakkonen P., Petrova T., Langer B., Raab I. (2004) Lymphatic neoangiogenesis in human kidney transplants is associated with immunologically active lymphocytic infiltrates. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15, 603–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Suzuki-Inoue K., Kato Y., Inoue O., Kaneko M. K., Mishima K., Yatomi Y., Yamazaki Y., Narimatsu H., Ozaki Y. (2007) Involvement of the snake toxin receptor CLEC-2, in podoplanin-mediated platelet activation, by cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25993–26001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suzuki-Inoue K., Fuller G. L., García A., Eble J. A., Pöhlmann S., Inoue O., Gartner T. K., Hughan S. C., Pearce A. C., Laing G. D., Theakston R. D., Schweighoffer E., Zitzmann N., Morita T., Tybulewicz V. L., Ozaki Y., Watson S. P. (2006) A novel Syk-dependent mechanism of platelet activation by the C-type lectin receptor CLEC-2. Blood 107, 542–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colonna M., Samaridis J., Angman L. (2000) Molecular characterization of two novel C-type lectin-like receptors, one of which is selectively expressed in human dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 697–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kerrigan A. M., Dennehy K. M., Mourão-Sá D., Faro-Trindade I., Willment J. A., Taylor P. R., Eble J. A., Reis e Sousa C., Brown G. D. (2009) CLEC-2 is a phagocytic activation receptor expressed on murine peripheral blood neutrophils. J. Immunol. 182, 4150–4157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suzuki-Inoue K., Inoue O., Ozaki Y. (2011) The novel platelet activation receptor CLEC-2. Platelets 22, 380–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uhrin P., Zaujec J., Breuss J. M., Olcaydu D., Chrenek P., Stockinger H., Fuertbauer E., Moser M., Haiko P., Fässler R., Alitalo K., Binder B. R., Kerjaschki D. (2010) Novel function for blood platelets and podoplanin in developmental separation of blood and lymphatic circulation. Blood 115, 3997–4005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bertozzi C. C., Schmaier A. A., Mericko P., Hess P. R., Zou Z., Chen M., Chen C.-Y., Xu B., Lu M.-M., Zhou D., Sebzda E., Santore M. T., Merianos D. J., Stadtfeld M., Flake A. W., Graf T., Skoda R., Maltzman J. S., Koretzky G. A., Kahn M. L. (2010) Platelets regulate lymphatic vascular development through CLEC-2-SLP-76 signaling. Blood 116, 661–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Acton S. E., Astarita J. L., Malhotra D., Lukacs-Kornek V., Franz B., Hess P. R., Jakus Z., Kuligowski M., Fletcher A. L., Elpek K. G., Bellemare-Pelletier A., Sceats L., Reynoso E. D., Gonzalez S. F., Graham D. B., Chang J., Peters A., Woodruff M., Kim Y. A., Swat W., Morita T., Kuchroo V., Carroll M. C., Kahn M. L., Wucherpfennig K. W., Turley S. J. (2012) Podoplanin-rich stromal networks induce dendritic cell motility via activation of the C-type lectin receptor CLEC-2. Immunity 37, 276–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Herzog B. H., Fu J., Wilson S. J., Hess P. R., Sen A., McDaniel J. M., Pan Y., Sheng M., Yago T., Silasi-Mansat R., McGee S., May F., Nieswandt B., Morris A. J., Lupu F., Coughlin S. R., McEver R. P., Chen H., Kahn M. L., Xia L. (2013) Podoplanin maintains high endothelial venule integrity by interacting with platelet CLEC-2. Nature 502, 105–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cueni L. N., Chen L., Zhang H., Marino D., Huggenberger R., Alitalo A., Bianchi R., Detmar M. (2010) Podoplanin-Fc reduces lymphatic vessel formation in vitro and in vivo and causes disseminated intravascular coagulation when transgenically expressed in the skin. Blood 116, 4376–4384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato Y., Fujita N., Kunita A., Sato S., Kaneko M., Osawa M., Tsuruo T. (2003) Molecular identification of Aggrus/T1α as a platelet aggregation-inducing factor expressed in colorectal tumors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51599–51605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zuberbühler K., Palumbo A., Bacci C., Giovannoni L., Sommavilla R., Kaspar M., Trachsel E., Neri D. (2009) A general method for the selection of high-level scFv and IgG antibody expression by stably transfected mammalian cells. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 22, 169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pyż E., Brown G. D. (2011) Screening for ligands of C-type lectin-like receptors. Methods Mol. Biol. 748, 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kerrigan A. M., Navarro-Nuñez L., Pyz E., Finney B. A., Willment J. A., Watson S. P., Brown G. D. (2012) Podoplanin-expressing inflammatory macrophages activate murine platelets via CLEC-2. J. Thromb. Haemost. 10, 484–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pyz E., Huysamen C., Marshall A. S., Gordon S., Taylor P. R., Brown G. (2008) Characterisation of murine MICL (CLEC12A) and evidence for an endogenous ligand. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1157–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Novak-Hofer I., Amstutz H. P., Haldemann A., Blaser K., Morgenthaler J. J., Bläuenstein P., Schubiger P. A. (1992) Radioimmunolocalization of neuroblastoma xenografts with chimeric antibody chCE7. J. Nucl. Med. 33, 231–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vigl B., Aebischer D., Nitschké M., Iolyeva M., Röthlin T., Antsiferova O., Halin C. (2011) Tissue inflammation modulates gene expression of lymphatic endothelial cells and dendritic cell migration in a stimulus-dependent manner. Blood 118, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valtcheva N., Primorac A., Jurisic G., Hollmén M., Detmar M. (2013) The orphan adhesion G protein coupled receptor GPR97 regulates migration of lymphatic endothelial cells via the small GTPases RhoA and Cdc42. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 35736–35748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang H., Grimaldo S., Yuen D., Chen L. (2011) Combined blockade of VEGFR-3 and VLA-1 markedly promotes high-risk corneal transplant survival. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 6529–6535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iizuka K., Naidenko O. V., Plougastel B. F., Fremont D. H., Yokoyama W. M. (2003) Genetically linked C-type lectin-related ligands for the NKRP1 family of natural killer cell receptors. Nat. Immunol. 4, 801–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scholl F. G., Gamallo C., Vilaró S., Quintanilla M. (1999) Identification of PA2.26 antigen as a novel cell-surface mucin-type glycoprotein that induces plasma membrane extensions and increased motility in keratinocytes. J. Cell Sci. 112, 4601–4613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Astarita J. L., Acton S. E., Turley S. J. (2012) Podoplanin: emerging functions in development, the immune system, and cancer. Front Immunol. 3, 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leppänen A., White S. P., Helin J., McEver R. P., Cummings R. D. (2000) Binding of glycosulfopeptides to P-selectin requires stereospecific contributions of individual tyrosine sulfate and sugar residues. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39569–39578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaneko M. K., Kato Y., Kitano T., Osawa M. (2006) Conservation of a platelet activating domain of Aggrus/podoplanin as a platelet aggregation-inducing factor. Gene 378, 52–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kato Y., Kaneko M. K., Kunita A., Ito H., Kameyama A., Ogasawara S., Matsuura N., Hasegawa Y., Suzuki-Inoue K., Inoue O., Ozaki Y., Narimatsu H. (2008) Molecular analysis of the pathophysiological binding of the platelet aggregation-inducing factor podoplanin to the C-type lectin-like receptor CLEC-2. Cancer Sci. 99, 54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schacht V., Ramirez M. I., Hong Y.-K., Hirakawa S., Feng D., Harvey N., Williams M., Dvorak A. M., Dvorak H. F., Oliver G., Detmar M. (2003) T1α/podoplanin deficiency disrupts normal lymphatic vasculature formation and causes lymphedema. EMBO J. 22, 3546–3556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martín-Villar E., Megías D., Castel S., Yurrita M. M., Vilaró S., Quintanilla M. (2006) Podoplanin binds ERM proteins to activate RhoA and promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4541–4553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hess P. R., Rawnsley D. R., Jakus Z., Yang Y., Sweet D. T., Fu J., Herzog B., Lu M., Nieswandt B., Oliver G., Makinen T., Xia L., Kahn M. L. (2014) Platelets mediate lymphovenous hemostasis to maintain blood-lymphatic separation throughout life. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 273–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Finney B. A., Schweighoffer E., Navarro-Núñez L., Bénézech C., Barone F., Hughes C. E., Langan S. A., Lowe K. L., Pollitt A. Y., Mourao-Sa D., Sheardown S., Nash G. B., Smithers N., Reis e Sousa C., Tybulewicz V. L., Watson S. P. (2012) CLEC-2 and Syk in the megakaryocytic/platelet lineage are essential for development. Blood 119, 1747–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Osada M., Inoue O., Ding G., Shirai T., Ichise H., Hirayama K., Takano K., Yatomi Y., Hirashima M., Fujii H., Suzuki-Inoue K., Ozaki Y. (2012) Platelet activation receptor CLEC-2 regulates blood/lymphatic vessel separation by inhibiting proliferation, migration, and tube formation of lymphatic endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 22241–22252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaneko M., Kato Y., Kunita A., Fujita N., Tsuruo T., Osawa M. (2004) Functional sialylated O-glycan to platelet aggregation on Aggrus (T1α/Podoplanin) molecules expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38838–38843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]