Abstract

Background

Embarrassment is emphasized, yet scantily described as a factor in extreme dental anxiety or phobia. Present study aimed to describe details of social aspects of anxiety in dental situations, especially focusing on embarrassment phenomena.

Methods

Subjects (Ss) were consecutive specialist clinic patients, 16 men, 14 women, 20–65 yr, who avoided treatment mean 12.7 yr due to anxiety. Electronic patient records and transcribed initial assessment and exit interviews were analyzed using QSR"N4" software to aid in exploring contexts related to social aspects of dental anxiety and embarrassment phenomena. Qualitative findings were co-validated with tests of association between embarrassment intensity ratings, years of treatment avoidance, and mouth-hiding behavioral ratings.

Results

Embarrassment was a complaint in all but three cases. Chief complaints in the sample: 30% had fear of pain; 47% cited powerlessness in relation to dental social situations, some specific to embarrassment and 23% named co-morbid psychosocial dysfunction due to effects of sexual abuse, general anxiety, gagging, fainting or panic attacks. Intense embarrassment was manifested in both clinical and non-clinical situations due to poor dental status or perceived neglect, often (n = 9) with fear of negative social evaluation as chief complaint. These nine cases were qualitatively different from other cases with chief complaints of social powerlessness associated with conditioned distrust of dentists and their negative behaviors. The majority of embarrassed Ss to some degree inhibited smiling/laughing by hiding with lips, hands or changed head position. Secrecy, taboo-thinking, and mouth-hiding were associated with intense embarrassment. Especially after many years of avoidance, embarrassment phenomena lead to feelings of self-punishment, poor self-image/esteem and in some cases personality changes in a vicious circle of anxiety and avoidance. Embarrassment intensity ratings were positively correlated with years of avoidance and degree of mouth-hiding behaviors.

Conclusions

Embarrassment is a complex dental anxiety manifestation with qualitative differences by complaint characteristics and perceived intensity. Some cases exhibited manifestations similar to psychiatric criteria for social anxiety disorder as chief complaint, while most manifested embarrassment as a side effect.

Background

Most studies of the symptomatology of dental treatment anxiety have focused on the contributions of pain or unpleasant experiences [1-6], traumatic experiences [3-5] and co-morbidity with other anxiety and mood complexes [2,7-9]. Although some have also reported feelings of lack of control, powerlessness and embarrassment in dental treatment situations as contributing factors [4,7-10], actual mechanisms and other details of these psychosocial factors have not been thoroughly described.

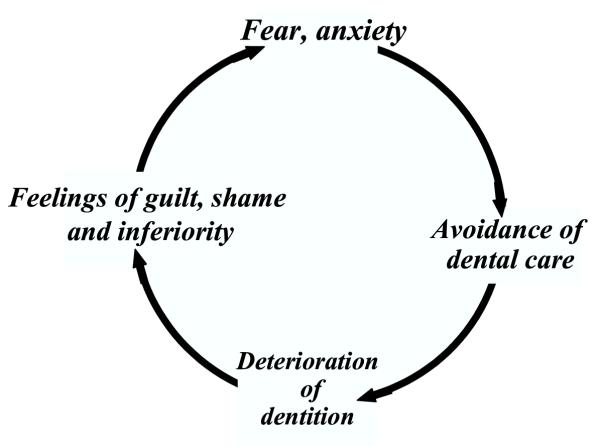

Earlier Scandinavian studies [7,8,11,12] indicated existence of a vicious circle of dental anxiety, in which embarrassment, shame or guilt have a central role in facilitating both anxiety and treatment avoidance, but they gave few details as to the exact role of embarrassment in this vicious circle (see Fig. 1). Since symptomatology and clinical significance are important in differential diagnosis of anxiety disorders, it seems that the influences of embarrassment, shame or guilt on dental anxiety have been relatively neglected in the literature. Inspite of the fact that the dentist-patient clinical situation is a social situation and that several studies have also pointed to negative dentist behavior as highly anxiety provoking [4,7,8,11,13-16], descriptions of possibilities for the existence of social anxiety, defined as intense fear of negative evaluation [17,18] or humiliation [19] in social situations, have been few for patients suffering with dental anxiety [7,8,13].

Figure 1.

Vicious circle of dental anxiety as described by Berggren [11]

Recent medical literature [18,20-22] has drawn attention to primary care occurrences of social anxiety disorder or phobia. They suggest that perhaps practitioners and counselors are focused on other problems than social anxiety or judge that feelings of embarrassment, shame or guilt are only secondary to more concrete problems, such as specific phobias or presence of other co-morbid anxiety or mood disorders. Thus, social anxiety and phobia are described as substantially under-diagnosed in both clinical and non-clinical samples [19-21]. Some [19,22] have questioned the adequacy of present methods in differentiating the existence of social anxiety disorder as principal diagnosis in both clinical and non-clinical populations. This is currently accomplished using a standard interview schedule of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [23], the Standard Clinical Inventory of Disorders – Patient version (SCID-P)[24]. Examples used in the SCID-P interview for social anxiety are fear of negative social evaluation with speaking, eating or writing. This would result in anxious dental patients rarely being diagnosed with social anxiety disorder or phobia, when fear of negative scrutiny in clinical social contexts might otherwise be a chief complaint and possible principal diagnosis. There has been a call for more case study research on the topic of social anxiety criteria in medical and other social contexts in order to discover new situations in which this nominal data category may arise, also as principal diagnosis [19,22]. An International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety proposed guidelines for distinguishing social anxiety disorder from other anxiety disorders [17] as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical features distinguishing social anxiety disorders from other anxiety disorders (adapted from Ballenger et al. [17, 18]

| * Anxiety precipitated by social interactions or performance situations |

| * Unique cognitions of negative evaluation by others |

| * Blushing, palpitations, sweating, tachycardia, trembling are characteristic |

| * Onset in childhood or adolescence |

| * Impairment usually leads to avoidance of named social and performance situations |

There can be confusion about the terms themselves, since in the course of daily conversation they are often used interchangeably. The main differences are that embarrassment and shame are associated with personal response to public scrutiny about moral conventions or loss of self-esteem, while guilt ("bad" or "guilty conscience") is thought of as self-scrutiny with breach of personal standards [25]. When it is referred to as a specific emotion, embarrassment is described as more fleeting in duration and has less serious consequences [25] than shame. However, embarrassment is also used as a more general term [4,7,16,26]: an emotional reaction (shame or guilt) to unintended and/or unwanted social predicaments or transgressions [26]. In the present study, we use the term embarrassment as this general term, unless otherwise specified.

The aim of the present study was to describe details of social aspects of anxiety in dental situations, especially focusing on embarrassment phenomena and their contribution to manifestations of extreme or phobic dental anxiety.

Methods

Subjects were 30 consecutive Danish adult patients from the Dental Phobia Research and Treatment Center (16 men, 14 women), aged 20–65 yr, who had avoided dental treatment for a mean of 12.7 years due to anxiety. 63% were self-referred as a result of mass media attention and/or friends or family urging, while 37% were professional referrals (physicians 20%; dentists 17%). Previously published research inclusion criteria included: 1) extreme or phobic dental anxiety (Dental Anxiety Scale score = 15 (max. 20), 2) a need for dental treatment, and 3) ages ca. 18 to 65 yr. Patients at the specialist center filled out psychometric questionnaires previously described in the literature [27] which included Corah's Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS)[28], Dental Beliefs Survey (DBS) [29] covering aspects of patient perceptions about relations with dentists, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait subscale (STAI-T)[30] covering general anxious anticipation, and a modified FSS-II Geer Fear Scale (GFS)[31] covering existence and intensities of other fears. Table 2 has sample statistics and normative scores for DAS, GFS, STAI-T [27] and DBS [32].

Table 2.

Sample summary statistics (N = 30)

| Age (yr) | Years avoiding dentist | CDAS | GFS | STAI-T | DBS | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 45.1 | 9.9 | 20–65 | 12.7 | 9.1 | 0.5–37.5 | 17.8 | 2.1 | 37.6 | 15.5 | 39.3 | 12.1 | 44.2 | 13.1 | |

| Normative scores* | 9.0 | 39.1 | 38.6 | 30.1 | ||||||||||

* Standard mean scores of psychometric tests on normal populations

Subjects were asked the following questions in audio-taped initial fear assessment interviews: 1) "When was your last dental visit? How did it go? 2) "What is the worst thing for you about dental visits?" 3) "Try to tell in your own words about your fear of dental treatment. Where do you think it started?" 4) "Have there been any special experiences related to this? " (If so: How old were you?) 5) "Do your friends or family know about your dental anxiety? (If so: How do they react to it?) 6) "Do you feel that the condition of your teeth influences your relations to family and friends in any way?" 7) "Is there anything in your background that makes it so that you would be so afraid (besides any bad dental experiences)?" 8) "Are there other things that you are as afraid of?" (Specify: Doctors? Hospitals?) 9) "How do you experience yourself under stressful conditions?"

In an exit interview after treatment completion, patients were asked: 1) "What helped you most to get over your dental anxiety?", 2) "What helped you next most?" and 3) "Are there other things besides resolution of your dental anxiety that you have learned here?". Such questions intended to provide a retrospective validation of initial chief complaint or indicate changes in diagnostic type as well as assess efficacy of treatment strategy for the type [33].

In all interviews, unstructured follow-up questions were also employed to encourage descriptive detail e.g., "Could you tell me more about 'such and such'?" or confirmations of meanings e.g., "So you mean that you are embarrassed about your teeth?"

Although analysis of qualitative descriptions was the main research method, embarrassment intensity and degree of mouth-hiding behaviors were also scaled to check for associations with each other and with years of treatment avoidance for conceptual validation and explanatory purposes. An embarrassment intensity rating scale was devised in which Ss were rated by the first and second authors from 0 = "no embarrassment" to 1 = "little", 2 = "some", 3 = "much" and 4 = "very much embarrassment or principal problem" based on clinical records and transcript material. (Kappa statistic for the two raters concurred at 0.79, P < .001.) Patient transcription reports about symptoms of not being able to smile or laugh fully and mouth-hiding during social interactions were coded: 0 = "none", 1 = "unspecified inhibitions or hiding – low degree", 2 = "hiding with lip or tongue only" and 3 = "combined hiding with lip or tongue and hiding with hand or head behaviors".

All subjects participated after written and verbal informed consent, in accordance with local ethics committee standards and the Helsinki declaration.

Analysis

Patients' electronic clinical records and all audio-taped interviews were transcribed verbatim and saved in "text only" raw files after appropriate measures to assure anonymity of clients and their previous dentists. These text files of patient records and interviews were then imported into Qualitative Solutions Research "N4" software [34] in order to aid exploration of categories or contexts related to social aspects of dental anxiety as well as embarrassment phenomena. The program basically aids in "cut and paste" procedures in examining evidence to support categorical analyses. Spearman's rho (rs) correlations, odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and Chi-square tests were used for analysis of associations between quantifiable variables. Statistical significance of tests were set at P = 0.05, but this was only used to indicate meaningful relationships between variables, not as a claim to statistical inference to representativity, since this is unknown.

Results

Sample characteristics

Three Ss did not complete therapy; two dropped out after three appointments and one was satisfied with two consultations. The 30 Ss were demographically and psychometrically (Table 2) similar to those previously described for present specialist clinic [27]. They received cognitive-behavioral therapy and limited dental treatments for a mean of 15.3 appointments (SD = 6.1).

Twelve Ss of the 30 had mentioned general anesthesia in initial interviewing, where 8 thought of it initially as a possible "quick fix" solution to their problems. Three had tried it as children and had negative experiences and therefore didn't think of it as a solution. One client had never tried it, but when a physician offered to refer him, he was too afraid. For 66.7% of Ss, self-reported age of onset was 12 yr. or less. Mean age of onset was 15.1 yr. (SD = 9.7; range = 5.5–43 yr.).

Although not usually chief complaints, incidence of embarrassment was substantial in this sampling. When asked about the condition of their teeth or effects on social relationships, all but three of the Ss expressed some degree of embarrassment about their dental fear problem or its consequences.

Chief complaints

Chief complaint at initial consultation for 9 Ss was pain, while 14 Ss cited "the whole process", referring to social aspects of the dental care situation and specifically named powerlessness or lack of control in the dental environment as the main problem. Seven Ss described co-morbid psychosocial dysfunction mostly related to general anxiety as a reason for seeking specialist treatment for dental anxiety, but none complained of depression at the time of interviews. Seven Ss had had previous psychiatric care. Nine patients described a generally discordant childhood, including 3 cases of sexual abuse. Moods disorders or depression was never a chief complaint among these subjects.

Thus, 47% of Ss expressed a sense of powerlessness about the whole dental situation as chief complaint, implying in relation to dentists or other personnel. Although several other Ss described feelings of a lack of control in the situation, it was secondary to other chief complaints or specific problems such as fear of anesthesia failure, panic attacks, choking or due to generally anxious feelings perceived as uncontrollable. Thus, the term "social powerlessness" was used in the following chief complaint analysis, since patients most often used the Danish terms for "powerless" or "powerlessness" to designate feelings of lack of control in relation to the dentist or staff. A qualitative analysis about chief complaints of feelings of social powerlessness was first undertaken in order to differentiate embarrassment from other possible types of social powerlessness. Then, analyses of both clinical and non-clinical manifestations specific to categories and characteristics of the phenomenology of embarrassment followed. English translations of all Danish transcript passages were checked among the three bilingual authors.

Social powerlessness as chief complaint associated with anxiety in dental care situations

In the present study, patient perceptions and descriptions about powerlessness in social interactions with the dentist were of two categories: 1) Social powerlessness associated with conditioned distrust of dentists' behaviors e.g. "I am afraid of how the dentist will do what he has to do and that I can't stop him." This could also include secondary embarrassment, since subjects' own behaviors or cognitions can seem out of control, e.g. "My reactions get so out of control sometimes that it's embarrassing." and 2) Social powerlessness primarily associated with embarrassment about anxiety, dental care neglect and treatment avoidance or appearance e.g. "I am afraid of what the dentist or others are thinking about me and how bad my teeth are or how long it has been since I had treatment." This did not preclude complaints of conditioned distrust of dentists in some cases, but these were secondary to the chief complaint or reason for seeking therapy. Case studies below illustrate the two types of social powerlessness.

Social powerlessness as conditioned distrust of dentist behavior

Descriptions of humiliating or physically traumatic events in an uneven power struggle with dentists filled this category of negative dentist behaviors as illustrated in the following case study.

Case #21 35 yr old day care mother (35 F) had last been to the dentist 7 years ago for emergency care. As a 10 yr old girl, she was forced against her will to have an operation to reposition an impacted canine tooth. The mother had accompanied her to the clinic and had originally given permission for the operation. But she protested at the last minute when she saw how frightened her daughter became. She was asked to leave the operatory and the operation was performed behind closed doors.

35 F: "And I remember that I screamed like a wild animal.. that I didn't want them to do it. So they just closed the door into the clinic, then in come a couple more assistants and I was held down here (shows on her arms and legs). Then they told me that I had a choice. Either I would lie still and they could get it over with quickly or I would be held down and it would take a long time. It was my choice. And that's how it was." (She cries.)

In this case, the resultant reaction was a dreadful anxiety about being entrapped and "forced" into treatment situations, akin to claustrophobia. Her presenting symptoms of crying whenever in the dental chair provoked embarrassment secondarily. The patient described her struggle to gain control over the irrational feelings of a perceived threat from not knowing what dentists might do.

35 F: "...normally I can say to myself, 'Just try it. It only takes 10 minutes... like going to the doctor and getting a gynecological checkup. Try to relax and breathe all the way down to your big toe and in about 2 minutes it will all be over.' What irritates me most (about at the dentist) is that you can't have control at all over what is happening. A wire just short circuits up in my head. It's horrible, really terrible."

RM: "You are just afraid that---?"

35 F: "Just suddenly he would pull out something or other (instrument).. "

Social powerlessness primarily associated with embarrassment

Feelings of powerlessness related to the embarrassment of revealing years of dental neglect to dentist and staff had developed as the main reason for dental treatment avoidance for this category, even though there may have been other reasons at the beginning of the avoidance history. Symptoms of embarrassment were also manifested outside clinical settings, indicating that complexities of shame and guilty conscience about avoiding treatment were not the only manifestations of this type of social powerlessness. Embarrassment was the main reason for seeking therapy, where other usually highly motivating factors such as pain, were not. These complexities are illustrated in the following case.

Case #3 A 36 yr old career business-woman (36 F) had avoided dental treatment 13 years and was embarrassed to admit it to her family and co-workers. Whereas 10 years ago her dental anxiety had been coupled to negative cognitions of dental procedures, it had now turned into something else. She tried to keep it a secret from family and co-workers, but had great difficulty, considering the toothache pains she experienced periodically. Since she could not face the problem without professional help, oral neglect led to a bad conscience and conflicts about her own image as mother and career woman since at home and work she was known as a "take charge" kind of person by her own description.

RM (first author): "What is the worst thing, when you think about going to the dentist?"

36 F: "Today it would perhaps have something to do with being embarrassed about the condition of my teeth. But 10 years ago they were not as bad as they are today. And I don't know if it is the (feelings of) powerlessness that made it so... but I simply couldn't foresee these consequences. I can't really explain it."

RM: " So it has come to that the embarrassment is actually the biggest barrier?"

36 F: " Yes. If you don't take care of your teeth, you get pain. And the pain, it really gets bad sometimes, where I need pain killers for it. Then I've often thought when I've had toothache, 'If I had (only) been to the dentist. It couldn't hurt more than this!' But from there to take the steps (dental visit), ... they are miles apart. "

RM: "So the anxiety is worse than the pain, in a way?"

36 F: Yes... yes!

This exemplifies the plight of many patients with phobic dental anxiety who have thoughts and feelings that the problem is bigger than themselves or their physical pain, and as in this case, was specifically related to embarrassment about getting started after a longer period of treatment avoidance.

Embarrassment phenomena and characteristics

The embarrassment category identified above as chief complaint (n = 9) manifested for Ss both at the dentist office when showing their mouths to dental personnel and having to admit to long periods of neglect and anxiety, as well as in general embarrassment or shame about dental neglect with inhibited smiling or dysfunctions in other social situations. Sixty-three percent of the sample described and were observed with symptoms of not being able to smile or laugh fully or had learned to cover their teeth with a hand, lip or tongue during social interactions. Blushing was also commonplace, especially at oral examinations. Other embarrassment phenomena, whether in clinical or non-clinical settings, were bad conscience/self-punishment, secrecy/taboo-thinking, poor self-image/esteem and in some cases, social withdrawal and personality changes. Six patients expressed feelings of inferiority based on their dentist avoidance and/or shame about their facial appearance and tended to avoid other people.

Bad conscience / self-punishment

Social circumstances for embarrassment were often linked to bad conscience about years of neglect where avoiding dental care was often seen as a sign of personal failure or inadequacy leading to self-punishment and associated poor self-image/esteem. The following case study exemplifies this:

Case #18 50 yr male (50 M) computer programmer was embarrassed about having avoided dental treatment for 26 yr and he described embarrassment characteristics as a personal failure in that regard:

50 M: " I feel as if I may have been punishing myself. I feel awful with the fact that I have not been able for that period of time to go regularly to the dentist. I think it is really bad of me. It is like a personal failure in some way that I wasn't able to take care of it."

RM: "So you see yourself as a rational human being and that was irrational?"

50 M: "Exactly. It is that that is my problem, because in my daily life I am used to thinking rationally and I can even criticize other people if they react so irrationally... since I do it also myself ... I don't know if I can say it is a double standard, but it is something like it. It gives cause for self-punishment. ..It's just too bad that I couldn't deal with it."

He went on to describe that his social inhibitions had lead him to a generally poor self-image.

Two subjects also indicated they felt embarrassed at the dentist because they might be "troublesome patients" for dentists. Neither subject experienced a high degree of embarrassment intensity.

Secrecy / taboo-thinking

Many patients had developed secrecy rituals that had to do with social taboos in talking about the topic of going to the dentist or the condition of their oral health. Taboo-thinking with rituals of secrecy both at work (11/30) and with family members (6/30) was observed and was associated with descriptions of bad conscience or poor self-esteem in patients (n = 11) who had been avoiding treatment for more than the mean number of years (12.7 yr) of treatment avoidance. This subgroup had mean 18.2 yr of avoidance. Some of these patients expressed fear that their teeth or mouths were being observed and were negatively evaluated by others. The following case study illustrates these relationships.

Case #8 51 yr old passenger ferry captain (51 M) who had avoided treatment for 23 years and who had carefully guarded his secret until recent events at his workplace:

51 M: "Clearly I haven't felt good about that I haven't done anything with my teeth for so many years. I just don't talk about it with anyone. That's the way it is."

RM: "Taboo?"

51 M: "Yes, because generally I am a very reasonable person and I don't want anyone to discover that I have a hard time with something."

RM: "But when someone talks about dentists?"

51 M: "I don't talk much about it."

RM: "In your social circle?"

51 M: "Yes, I keep my mouth shut. I hadn't even said anything to my wife about it. She has actually first now learned about it yesterday that I was coming here (therapy)."

RM: "So it's a secret?"

51 M: "It's a secret." (nodding confirmation).

RM: "And it is a secret that you want to get rid of?"

51 M: "Yes, of course I would like to get to the point where I can say like anyone else, 'Now I have also been to the dentist and everything is OK."

He continued to explain after treatment completion:

51 M: "(Now) I can talk freely about going to the dentist It had been taboo before. It affected me in relation to others... that I have had to hide something. I had always feared that someone (would say) 'When have you been to the dentist?' Therefore, if people started talking about the dentist, I changed the topic... because then I wouldn't get that question. And I would have been terribly embarrassed if I had to say 'It has been darn many years ago.' It has been like a symptom every single time I have opened my mouth, that one could see those two front teeth. So I thought, 'You must get them fixed!' I can tell you that it really is a load off my mind to be able to talk about going to the dentist.".

Poor self-image or self-esteem

As a symptom of embarrassment, poor self-image/esteem was cognitively manifested in two ways. Self-esteem problems were related to 1) job or professional image in which avoiding dental care and having bad teeth was not fitting to social status, which again returns to secrecy and taboo as in the example above or 2) how their children would see them or if a child would "catch" dental anxiety from them. The case of the ferry captain above is an example of self-esteem problems related mostly to career image. Here is an example of how phobic patients could worry about affecting their children:

Case #12 41 yr old quality control expert (41 M) who had avoided dental care for 12 years had never gotten over bad experiences that he had had with a dentist in his childhood. The many years of avoidance and neglect of painful dental conditions had set his beliefs about dentists and created a bad conscience that had affected his self-image and self-esteem. He stated in this regard:

"I hope that that (going to the dentist and having self-respect) can happen in the not too distant future, because it hurts like hell, especially since I have two small children to whom I try to explain about how important it is take care of their teeth. It wouldn't be very credible, and children can quickly sense such things about a person."

With analysis of these cases, self-image/self-esteem seemed to become an important driving concept for embarrassment/shame, i.e. the belief that "neglecting yourself" leads to poor self-esteem as related to societal norms and values. In other words, poor self-esteem was the result of a chronic condition of many years of neglect, secrecy, and feelings of shame and bad conscience. In many cases, the chronicity of the problem lead to social withdrawal and personality changes.

Social withdrawal and personality changes

Nine of the 30 Ss mentioned that they underwent changes in their personality as a result of long periods of time with dental neglect, bad conscience, poor self-image or self-esteem and social withdrawal. The following case report revealed that chronic dysfunctional embarrassment, and specifically fear of negative social evaluation associated with anxiety and avoidance, can lead to personality change.

Case #22 33 yr old factory worker (33 M) had experienced painfully traumatic root canal treatments on his two upper canine teeth as a 12 yr old child. His last emergency dental visit had been 7 years ago. He admitted to embarrassment and despair about the appearance of his teeth. It had affected his personality and eventually contributed to a divorce with his wife.

33 M: "... I don't know if you have noticed, but I don't smile so that you can see my teeth. My wife has nice teeth and is very happy and smiles a lot. She misses getting a smile from me once in a while. When we met about 14 years ago, I smiled a lot. I liked to tell jokes and make fun with people and laugh. But it has become less and less, where now I go more alone with myself."

RM: "Why do you think it is that you don't smile?"

33 M: "It's because my teeth are ugly and because I am missing teeth."

RM: "Are you saying that you are embarrassed about your teeth?"

33 M: "Yeah, I am a lot."

RM: "Do you think that you have undergone a change in your personality because of your embarrassment?"

33 M: "Yeah, it has been coming on as of about 6 to 8 years ago.... Actually, I am positive and happy, but I don't smile by showing my teeth... If someone tells a joke that I would laugh at, I really have to fight back doing it (laughing). So in that way, there are many times where I really don't listen carefully when someone tells a joke, since I can't allow myself to break out in a good laugh. I just can't allow myself. ... It is a sad state of affairs when you have to be embarrassed about your smile and to admit that you are afraid to go to the dentist. So I talked with my physician about sending a referral to your clinic."

Patients often first realized that they had undergone negative personality changes only after they had completed or nearly completed therapy. In contrast to how they had been before, they could sense an improved self-image and /or self-confidence they had acquired during therapy. The following case illustrates important reflections at exit interviews.

Case #24 44 yr old female day care mother (44 F) originally saw herself as a person with a "deep-dark secret" in which others could not "pass through" and she made all attempts to avoid contacts with new people, also hiding her teeth with both lips, hands and head gestures. She had suffered from a self-admitted inferiority complex about her mouth for over 20 years. Now she reflects upon the changes that had occurred for her at the conclusion of therapy.

44 F: "Yesterday when I sat and was talking with someone, I noticed she kept looking at my mouth. Then my hand went up (in front of my face) and I thought, 'OK, hello, I can still fall back into the old pattern!' This was a very, very good girlfriend. One who knows that I have been coming here (for therapy). I removed my hand again... Since we had removed what I thought everyone else was looking at (tarter buildup on front teeth), about which I was so embarrassed... I didn't have anything to be embarrassed about anymore. I told someone else a few days ago that I was having therapy here and had done so for 1 1/2 years because of my dental anxiety. I noticed that I was completely relaxed as I told it. A change had definitely occurred. I was a completely different person and I noticed the difference from before. It took a long time before I dared to tell anyone that I was in therapy for this, because it was embarrassing."

RM: "So in some way, has there occurred a personality change?"

44 F: "You bet. Yeah, I notice that I feel more free, because I don't have to think about covering my mouth. I do still have it a little bit yet. But you can't just snap your fingers and say it's gone! And I still wonder if I have bad breath."

Co-validation of embarrassment intensity, phobic avoidance and mouth-hiding behaviors

Embarrassment intensity increased with years of dental care avoidance (rs = 0.44; P = 0.02). Ss were nearly twice (OR = 1.9; CI = 1.3–2.8) as likely to have highly intense embarrassment (scores 3 or 4) after 4 years of treatment avoidance (?2 = 4.3; P = 0.04), compared to lower embarrassment levels (scores 0–2). Embarrassment intensity also correlated with the mouth-hiding behavior scale (rs = 0.53; P = 0.003). The mouth-hiding scale was rs = 0.32; P = 0.09 with years of avoidance. With greater numbers of years avoiding dental treatment, the following phenomena were noted in descriptions among embarrassed subjects (multiple possible) 1) guilty conscience as attributed to the act of neglecting dental care (n = 19), 2) actual dental damage from neglect that was visible (n = 22) (e.g. Fig. 2) or 3) unrealistic, exaggerated perceptions of tooth damage that were not as visible as patients perceived and thus were incongruent with actual dental status (n = 10). The latter appeared most often in cases where there were perceptions of negative social evaluation, guilty conscience and/or poor self-image/esteem.

Figure 2.

Extreme oral destruction due to phobic avoidance of dental treatment in a 26 yr old Danish man

Discussion

The number of Ss in the present study was designed to be the minimum, manageable number necessary to capture a comprehensive range of embarrassment phenomena and characteristics. Although some caution must be advised in the interpretation of results, sampling is similar to previously described larger samples at the same clinic. The self-referral nature of the dental anxiety specialist clinic probably excluded patients with symptoms of mood disorders, depression, or agoraphobia in this clinical sample.

Clearly, some odontophobic patients have a perception of the dental environment as threatening beyond just the threat of physically painful treatment. Present results showed that chief complaints of social powerlessness in dental situations either resulted from conditioned distrust of dentist behaviors or embarrassment with decreases in self-esteem often leading to fear of negative social scrutiny. These latter complaints often appear to fulfill DSM psychiatric criteria for social anxiety disorder for this circumscribed area. This fear of negative social evaluation and associated poor self-esteem is comparable in many ways to other circumscribed specific social anxiety disorders, such as fear of scrutiny while speaking, eating, or writing and perhaps is just as socially and personally debilitating.

Indeed perhaps what is being described here is the process of suffering [35,36]. Researchers of suffering process Kahn & Steeves [36] have described it as, "Changes in personal identity may result from loss of function or changes in body image that are perceived as threats to self.". Feelings related to neglect of dental health care and poor appearance of the teeth were often associated with identity problems for many of the present cases. Perhaps to the routined private practitioner of dentistry, the oral cavity is a technical work place divided up into quadrants, where each tooth has its number and anatomical coordinates. But even a casual comment with a raised eyebrow as to "how long it has been since the last appointment" becomes a feared catastrophe for many phobic patients. Some might even quit a dental practice inspite of critical need for treatment of painful oral symptoms.

Berggren [11] first described the "vicious circle of dental anxiety" among a population of Swedish odontophobic patients in whom feelings of guilt, shame and inferiority catalyzed maintenance of fear and further avoidance (Fig. 1). Present results confirm this vicious circle and describe the embarrassment factor as an amplifier for anxiety, increasing the intensity of the phobic reaction, especially with more and more years of treatment avoidance. Although they did not refer directly to embarrassment or shame, Gale [15] and Stouthard and Hoogstraten [16] reported that negative dentist behaviors such as "Dentist laughs as he looks in your mouth." or "Dentist tells you that you have bad teeth.", in the social context of dental treatment are among the most intense anxiety stimuli. Their findings indicated that there may be a dimension of humiliation in the anxiety. In college students with high dental anxiety Bernstein et al [14] found that half cited negative dentist behaviors as the origin; 81 percent did not mention pain.

In results from Danish [7,8] and Swedish [37] dental anxiety studies of clinical samples similar to the present sample, there were similar findings of complicated psychiatric symptomatology specific to the dentist-patient situation. In a 1977 Swedish qualitative study, Bjercke et al [37] assessed 22 patients referred for specialist treatment of dental phobia. After extensive interviewing, they were classified according to "standard psychiatric nomenclature". Over half of the patients had a record of previous psychiatric problems or a discordant childhood. Twelve of the patients described feelings of inferiority based on their dental anxiety and avoided other people. They concluded that dental phobia was usually a more complex psychiatric syndrome that was puzzling, since it was more intensely experienced by patients than one would expect of other phobias. It also demonstrated the necessity to gain complete diagnostic information before planning interventions.

Regarding intensity with which patients can experience dental anxiety, much as Sheehan and Sheehan [33] described that outcomes of treatment can reveal accuracy of diagnoses in retrospect, results over 17-years at the Dental Phobia Research and Treatment Center has shown that in many cases improved efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy often was linked to a two phase course of treatment. Dependent on the intensity of embarrassment, shame or guilt presented by the client, the first phase was cognitive restructuring of social interactions with clients, where embarrassment, shame or guilt has been the primary focus. Desensitizations were first confined to the therapist-dentist as "object" (interpersonal distances and stepwise mouth exam sequence), if necessary. This "turned down the amplifier" so to speak, making it easier for the client to focus on the second, more instrumental phase of desensitization to dental instruments and procedures, often with surprising ease. This illustrates how awareness of embarrassment complexes is important to therapy for dental anxiety and as well as a need for further research.

Feelings of social powerlessness and embarrassment in dental situations were also the most important factors associated with phobic avoidance in nearly half of 80 patients in earlier Danish studies by Moore et al[7,8]. Although results indicated that the most frequent category was social phobia when comparing another diagnostic system with DSM terminology, the assessment was overestimated according to current social anxiety disorder criteria [17,18]. Many of these subjects probably exhibited learned distrust of dentist behaviors, which was confused with symptoms of social phobia. Liddell and Gosse [13] referred to the Danish studies described above and noted the distinction between conditioned social distrust at the dentist versus fears of negative dentist evaluation in a sample of graduate students with dental anxiety. Present results also confirm a clinical distinction between distrust of dentists versus embarrassment, shame or guilt as chief complaint and primary problem. This embarrassment was associated with 1) the act of self-neglect, 2) actual, visible tooth damage from neglect or 3) exaggerated perceptions of tooth damage associated with guilty conscience. In phobic distrust of dentist behaviors, embarrassment also presented as a secondary reaction.

Conditioned anxious distrust of dentists by DSM criteria would be a specific phobia, which is persistent fear in which an object or situation is avoided or endured with intense anxiety and significantly interferes with normal routines or relationships. Choice of therapeutic strategy for specific phobias requires primarily desensitization for fear reduction, while social anxiety related dental anxiety would primarily require cognitive reframing of social interaction contexts combined with interpersonal desensitization [38]. Thus, it is important that clinicians become attentive to the degree of embarrassment related to dental anxiety, where different intensity levels require different choices or sequences of therapeutic strategy.

There may be differences between Danish patients and other ethno-cultural groups of patients experiencing dental anxiety[39,40]. Moore et al[39,40] have indicated that distribution of type of dental anxiety and perceptions of painful procedures varies among different ethno-cultural groups. For example, the "Law of Jante" is perhaps a special phenomenon unique to Scandinavian populations that could facilitate embarrassment and fear of negative social evaluation [41,42] in general. Thus, hypothetically there could be a higher incidence of embarrassment and/or social anxiety disorder in Denmark or other Scandinavian countries than in other countries [43]. Given that DSM-IV psychiatric criteria have been coordinated with European standard criteria (ICD-10) [23], one would not expect international variation in diagnostic categories, but rather differences in their percentages of distribution from country to country.

Since they have broad implications for therapeutic outcome and relapse, there is a need to operationalize the meanings of specific "social situations" for diagnostic accuracy, since no standardized instrument can be used in all contexts for comparisons [17,18,22]. In dental clinical contexts, a start would be to ask clients, 1) "Are you uncomfortable or embarrassed about your mouth?" and 2) "Do you find it hard to interact with people in general (or 3) dentists or staff) due to your dental situation?". These are similar to recommendations made by the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety on future studies of social anxiety disorder [17]. A recently described scale measuring psychosocial effects of dental anxiety also appears to hold promise [10].

Conclusions

The complexities of phobic dental anxiety that baffled Swedish researchers in the late 1970s are perhaps only now beginning to be understood. Embarrassment is a complex dental anxiety manifestation showing clinical differences by complaint characteristics and perceived intensity. Some of present cases exhibited manifestations similar to psychiatric criteria for social anxiety disorder, while most manifested embarrassment as a side effect. Sensitivity and understanding about the psychosocial nature of the dental health care environment should be an aim in the education of dentists in the 21st century, in order to prevent and treat suffering from extreme or phobic dental anxiety and related dysfunctional phenomena.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

RM conceived and carried out the study, entered qualitative data, led the analysis and drafted the manuscripts. IB entered qualitative data and aided in transcription, data analysis and manuscript revision. NR aided in analysis and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Bente Kjær for transcription of interviews as well the Danish Dental Association for financial support (FUT Fund).

Contributor Information

Rod Moore, Email: roding@post8.tele.dk.

Inger Brødsgaard, Email: inbr@hs.vejleamt.dk.

Nicole Rosenberg, Email: nkr@psykiatri.aaa.dk.

References

- Johnson B, Mayberry WE, McGlynn FD. Exploratory factor analysis of a sixty-item questionaire concerned with fear of dental treatment. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatr. 1990;21:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(90)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale G, Raadal M, Vika M, Johnsen BH, Skaret E, Vatnelid H, Oiama I. Treatment of dental anxiety disorders. Outcome related to DSM-IV diagnoses. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:69–74. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.11204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jongh A, Aartman I, N. Brand. Trauma-related phenomena in anxious dental patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:52–58. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker D, Shapiro D, Liddell A. Negative dental experiences and their relationship to dental anxiety. Community Dent Health. 1996;13:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassend O. Anxiety, pain and discomfort associated with dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:659–666. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90119-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaakko T, Coldwell SE, Getz T, Milgrom P, Roy-Byrne PP, Ramsay DS. Psychiatric diagnoses among self-referred dental injection phobics. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14:299–312. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(00)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Birn H. Manifestations, acquisition and diagnostic categories of dental fear in a self-referred population. Behav Res Ther. 1991;29:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(09)80007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I. Differential diagnosis of odontophobic patients using the DSM-IV. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne PP, Milgrom P, Tay K-M, Weinstein P, Katon W. Psychopathology and psychiatric diagnosis in subjects with dental phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 1994;8:19–31. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(94)90020-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locker D. Psychosocial consequences of dental fear and anxiety. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:144–151. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance - causes, symptoms and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:247–251. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren U, Carlsson SG, Gustafsson JE, Hakeberg M. Factor analysis and reduction of a Fear Survey Schedule among dental phobic patients. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell A, Gosse V. Characteristics of early unpleasant dental experiences. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1998;29:227–237. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(98)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DA, Kleinknecht RA, Alexander LD. Antecedents of dental fear. J Public Health Dent. 1979;39:113–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1979.tb02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale EN. Fears of the dental situation. J Dent Res. 1972;51:964–966. doi: 10.1177/00220345720510044001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthard MEA, Hoogstraten J. Ratings of fears associated with twelve dental situations. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1175–1178. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660061601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Bobes J, Beidel DC, Ono Y, Westenberg HG. Consensus statement on social anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC. Recognizing the patient with social anxiety disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;15:S1–S5. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200007001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbe KJ. Uncharted waters: psychodynamic considerations in the diagnosis and treatment of social phobia. Bull Menninger Clin. 1994;58:A3–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce TJ, Saeed SA. Social anxiety disorder: a common, underrecognized mental disorder. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2311–2320, 2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzelnick DJ, Greist JH. Social anxiety disorder: an unrecognized problem in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 1:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker NJ, Goldenberg I, Rogers MP, Goisman RM, Warshaw MG, Fierman EJ, Vasile RG, Keller MB. Profile of a large sample of patients with social phobia: comparison between generalized and specific social phobia. Depress Anxiety. 1997;4:209–216. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:5<209::AID-DA1>3.3.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, DSM-IV. Washington, D. C., American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R - Patient Version (SCID-P, 5/1/89) New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N. Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:665–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Fukada H. A comparison of four causal factors of embarrassment in public and private situations. J Psychol. 2002;136:399–406. doi: 10.1080/00223980209604166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Berggren U, Carlsson SG. Reliability and clinical usefulness of psychometric measures in a self-referred population of odontophobics. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corah NL. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res. 1969;48:596. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Kleinknecht R, Getz T. Treating Fearful Dental Patients - A Patient Management Handbook. Second. Seattle, WA, University of Washington Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. STAI manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alta, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hakeberg M, Gustafsson JE, Berggren U, Carlsson SG. Multivariate analysis of fears in dental phobic patients according to a reduced FSS-II scale. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103:339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, Berggren U, Hakeberg M, Hirsch JM. Measures of dental beliefs and attitudes: their relationships with measures of fear. Community Dent Health. 1993;10:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH. The classification of phobic disorders. Int J Psychiatr Med. 1983;12:243–266. doi: 10.2190/lna4-1u6e-9wtw-31ju. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards T, Richards L. QSR (Qualitative Solutions and Research) Manual, NUD*IST (Nonnumerical Unstructured Data * Indexing, Searching and Theory building) London, Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell EJ. Diagnosing suffering: a perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:531–534. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn DL, Steeves RH. The experience of suffering: conceptual clarification and theoretical definition. J Adv Nurs. 1986;11:623–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1986.tb03379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjercke O, Blomberg S, Linde A. [Psychiatric evaluation of patients with pronounced fear of dental treatment] Psykiatrisk bedömning av patienter med tandvårdskräck. Läkertidningen. 1977;74:1390–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe J. The dichotomy between classical conditioned and cognitively learned anxiety. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatr. 1981;12:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(81)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Mao TK, Kwan HW, Shiau YY, Knudsen R. Fear of injections and report of negative dentist behavior among Caucasian American and Taiwanese adults from dental school clinics. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:292–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Mao T-K, Miller ML, Dworkin SF. Perceived need for local anesthesia in tooth drilling among AngloAmericans, mandarin Chinese and Scandinavians. Anesth Prog. 1998;45:22–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson B. The human values of Swedish management. J Human Values. 1995;1:153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J. About the Nordeners: Subject 2.6 The essence of Nordishness, 2.6.1 What is Janteloven? The Jante Law. http://www lysator liu se/nordic/scn/faq26 html. 1998.

- Kirmayer Laurence J. Cultural variations in the response to psychiatric disorders and emotional distress. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29:327–339. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]