Abstract

We report the case of a 67-year-old female who presented with a large renal mass. Gross examination of the nephrectomy specimen demonstrated a 6-cm renal mass that invaded into the renal sinus and perinephric fat. Histologic examination revealed two distinct tumor types. The first type was a conventional (clear cell) renal cell carcinoma that was of low nuclear grade and comprised the minority of the overall tumor. The second type was a high-grade collecting duct carcinoma with glandular/tubular differentiation and composed the majority of the tumor. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated distinctive patterns of the two tumor types, thus confirming two distinct lineages. Five months postoperatively, the patient developed metastasis to the lungs and right hilar lymph node region. A fine needle aspiration of a lung nodule demonstrated a metastatic, poorly differentiated carcinoma, similar to the collecting duct carcinoma component in the kidney. Collision tumors of the kidney are rare with fewer than 10 cases reported in the literature. Our report further expands the spectrum of this rare phenomenon.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, collision tumor, collecting duct carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma

Collision tumors refer to the phenomenon where two apparently different and unrelated tumor types are present within the same location in an organ, forming a single discrete lesion. Although the phenomenon has been well documented in other organ systems like the gastrointestinal tract and lungs, there is limited knowledge of this phenomenon within the kidney. Thus far, fewer than 10 cases of collision or “synchronous” renal tumors have been reported in the literature[1]–[8].

Herein, we report the case of a renal collision tumor composed of collecting duct carcinoma and clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) presenting as a solitary renal mass. On gross and microscopic examination, the tumor showed two distinct yet intimately associated components with divergent morphologies and immunohistochemical profiles.

Case Report

A 67-year-old female presented to the emergency room with abdominal pain secondary to diverticulitis and was found to have a large left renal mass. The patient's medical history was significant for hyperlipidemia and diverticulitis; however, there was no past or family medical history of urologic malignancies. Physical examination was positive for back and abdominal pain as well as urinary frequency. There was no history of hematuria noted. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an infiltrative mass arising from the upper pole of the left kidney, which was suggestive of RCC. A CT scan of the chest demonstrated punctate lung nodules of indeterminate significance. The patient underwent an uncomplicated left radical nephrectomy. There was no evidence of extrarenal tumor involvement noted at the time of the procedure. The radical nephrectomy specimen was routinely fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and serially sectioned into 4-µm-thick sections. Routine staining with hematoxylin and eosin was performed. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method in a Dako Autostainer (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) with standard techniques. Primary antibodies included CD10, PAX-8, vimentin, alpha-methyl-CoA Racemase (AMACR), PIN dual stain (cocktail of high molecular weight cytokeratin and p63), thrombomodulin, Ulex europaeus lectin, cytokeratin 7 (CK7), and cytokeratin 20 (CK20).

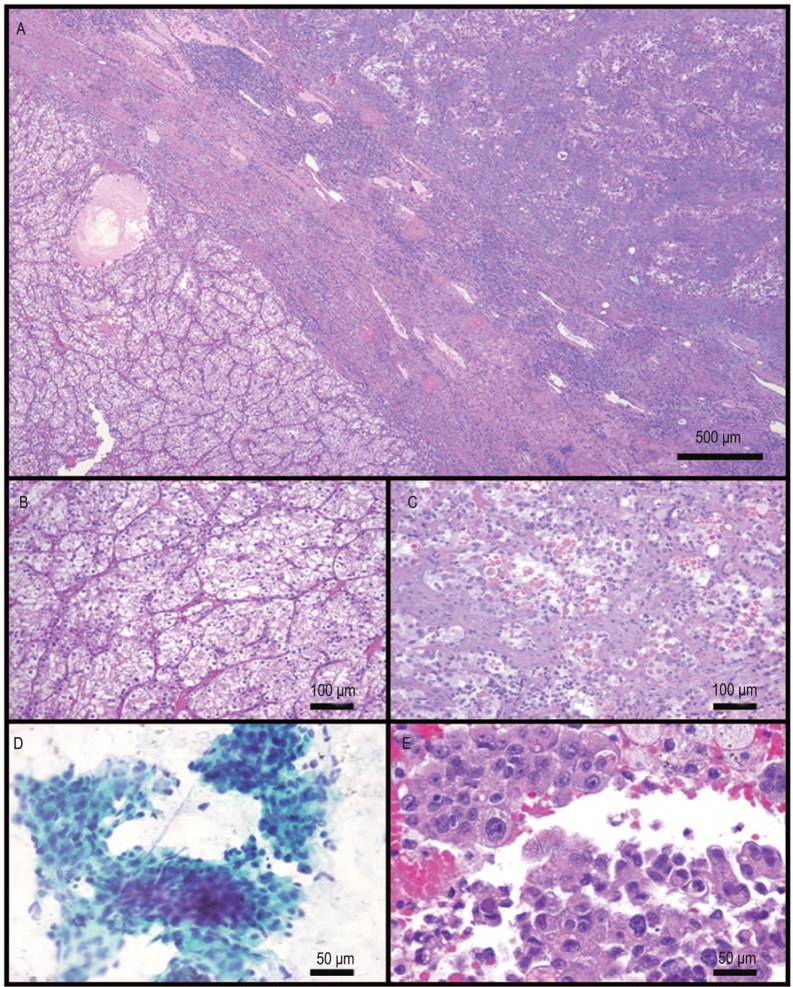

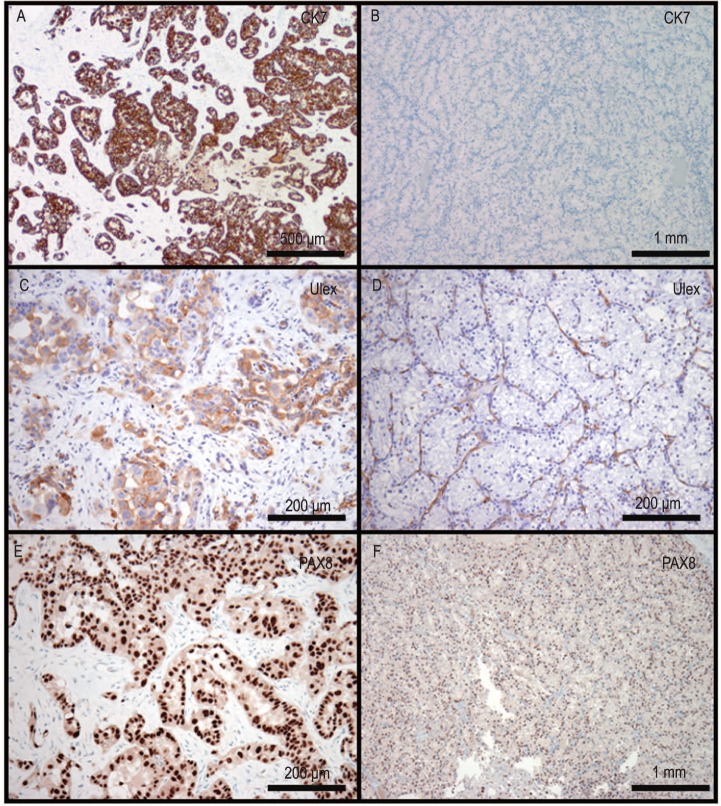

The nephrectomy specimen showed a 6.0 cm × 6.0 cm × 4.0 cm poorly circumscribed tumor in the upper pole of the kidney. Approximately 70% of the tumor cut surface was solid, fibrous tan-white, and 30% of that was soft, lobulated tan-yellow with focal areas of hemorrhage within the soft tan-yellow areas (Figure 1). Histologically, two distinct tumor types were noted. The first was a clear cell RCC, which corresponded to the bright yellow areas grossly identified within the tumor. The tumor cells in these foci were of low nuclear grade (Fuhrman nuclear grade 2). The second component, which comprised the majority of the tumor, corresponded to the white fibrotic areas within the tumor and was composed of a high-grade tumor with glandular/tubular differentiation (Figures 2A–C). This tumor was of high nuclear grade (Fuhrman nuclear grade 4) and was associated with extracellular mucin production and extensive desmoplastic stroma. Another unusual finding was the presence of extensive perineural invasion in this area, a feature that is rarely noted in renal tumors, as well as the presence of hyaline globules noted within the high-grade component.

Figure 1. Gross picture of the nephrectomy specimen showing two distinct tumor subtypes.

The majority of the tumor is gray-white and fibrotic and demonstrates collecting duct morphology (notched red arrow). Also identified is a soft yellow area that appears to be somewhat sharply demarcated from the above mentioned component, which histologically demonstrates clear cell histology (solid blue arrow).

Figure 2. Histologic features of the primary renal tumor as well as the metastatic tumor in the lung.

A, low power image demonstrates a sharp demarcation between the collecting duct carcinoma (top right) and clear cell carcinoma (bottom left). B, high power image demonstrates the low Fuhrman nuclear grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma component. C, the collecting duct carcinoma component is composed of a high-grade tumor with prominent glandular features. The background shows prominent desmoplasia. Also noted are numerous hyaline globules within the tumor. D, fine needle aspiration specimen from the lung metastasis demonstrates high-grade carcinoma. E, cell block preparation demonstrates high-grade carcinoma with histologic features similar to the renal collecting duct carcinoma. Also noted within the aspiration specimen are hyaline globules similar to those noted in the renal primary.

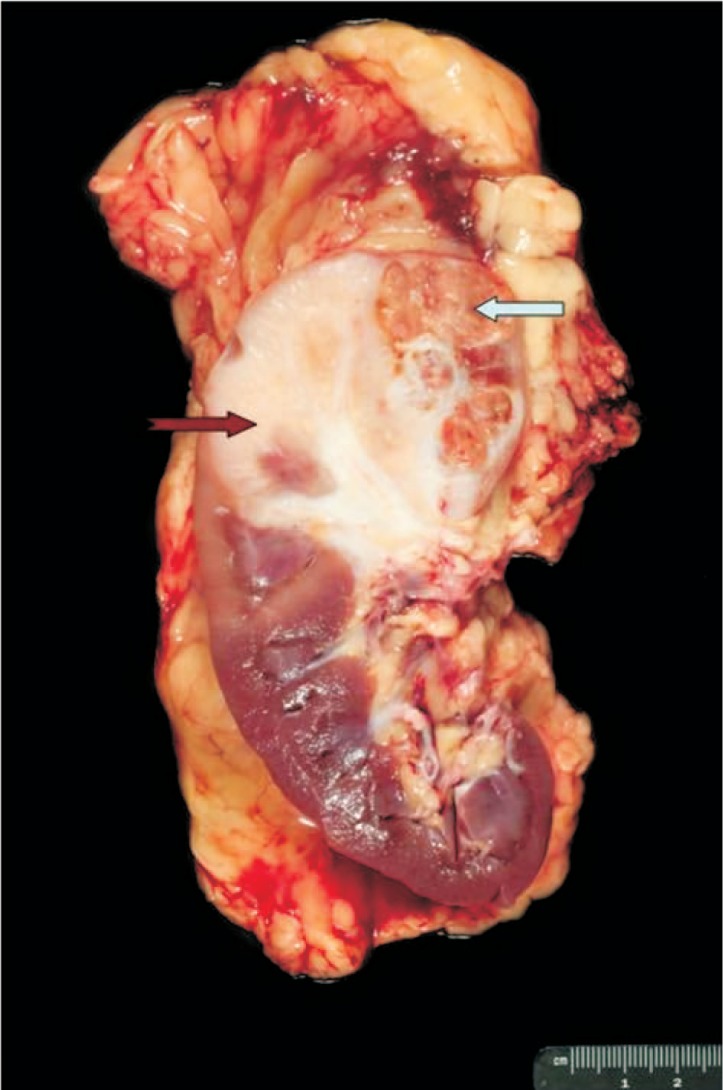

Immunohistochemical stains revealed that the clear cell component was positive for CD10, PAX-8, vimentin, and AMACR (P504S) and negative for PIN dual, thrombomodulin, Ulex europaeus lectin, CK7, and CK20. The high-grade component was positive for CD10, PAX-8, vimentin, Ulex europaeus lectin, and CK7; focally positive for AMACR; and negative for PIN dual, thrombomodulin, and CK20 (Figure 3). Although urothelial carcinoma was considered in the differential diagnosis, the lack of an in situ urothelial carcinoma component, coupled with the strong expression of PAX-8, vimentin, and Ulex europaeus lectin and the negative staining for PIN dual (cocktail of high molecular weight cytokeratin and p63), helped bolster the diagnosis of collecting duct carcinoma.

Figure 3. Immunohisto-chemical staining profile of the tumor.

A, C, and E demonstrate the collecting duct carcinoma are strongly positive for CK7, Ulex europaeus lectin, and PAX-8, respectively. The clear cell carcinoma is negative for CK7 (B) and Ulex europaeus lectin (D) and is positive for PAX-8 (F).

The histologic features and immunohistochemical profile of the higher-grade component were consistent with collecting duct carcinoma. Due to the close proximity of the two components, along with the presence of both the clear cell and the collecting duct carcinoma components at the interface, the tumor was best thought to represent a collision tumor, composed of clear cell RCC and collecting duct carcinoma.

Five months post-nephrectomy, the patient developed bilateral enlarged pulmonary nodules. A fine needle aspiration of the lung showed numerous three-dimensional cell clusters and papillary groups. The cells were of varying sizes, with granular cytoplasm. They showed high nuclear grade with nuclear overlap, hyperchromasia, and prominent nucleoli. There were also spindle cell desmosplastic stromal fragments. As in the primary renal tumor, intracellular and extracellular hyaline globules were present, seen especially on cell block sections. The findings were consistent with metastasis from the collecting duct carcinoma component of the primary renal tumor. There were no cells with features of clear cell carcinoma (Figures 2D–E).

The patient subsequently underwent combination chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatinum every three weeks. The patient had a clinical response, with decreased pain and improved performance status, and stable radiographic findings. After four cycles of treatment with paclitaxel and carboplatinum, she developed neuropathy necessitating a change of therapy and then proceeded to undergo doxorubicin and gemcitabine. She then developed clinical evidence of soft tissue and bone metastasis in the thoracic spine, for which she underwent radiation treatment. Despite undergoing treatment, the patient died due to disease progression, 14 months after initial diagnosis.

Discussion

Collision tumors arising in the kidney are unusual, with only a handful of cases documented thus far in the literature. The reported cases of renal collision tumors have included collecting duct carcinoma arising in conjunction with chromophobe RCC, or papillary RCC[2]–[5]. Other reported tumor combinations have included chromophobe RCC and oncocytoma arising in association with papillary RCC[5]–[7]. Cho et al.[1] reported a case of collision tumor of the kidney where the dominant tumor mass resembled a clear cell RCC. The tumor reportedly also demonstrated a smaller nodule with a tubulopapillary architecture that was felt to morphologically resemble a collecting duct carcinoma, despite the reported lack of immunohistochemical support (negative CK7, negative Ulex europaeus lectin)[1]. Our case, in contrast, showed typical morphology (high-grade tubulopapillary carcinoma with a desmoplastic stroma, juxtaposed with a low-grade clear cell component) as well as immunohistochemical characteristics of collecting duct carcinoma (strong expression of PAX-8, vimentin, and Ulex europaeus lectin and negative staining for PIN dual and thrombomodulin) in the high-grade component of the tumor.

The histogenetic basis of collision tumors is unclear. The existing theories include (a) two unrelated existing cell lines that simultaneously proliferate, thus resulting in two phenotypically different tumors; (b) tumors arising from a common precursor stem cell, which differentiates along two different lines into two unrelated neoplasms, and (c) incidental occurrence of two different isolated tumors within a common anatomic site. Because the two tumor types noted in this renal tumor had origins in the renal cortex (clear cell carcinoma) and the distal collecting duct (collecting duct carcinoma), any of the above theories may be applicable to our case, although the close proximity and abrupt transition between the two tumor types noted both grossly and microscopically may lend credence to the former two theories. Our patient developed disease progression, with bilateral pulmonary metastasis appearing within a few months after nephrectomy. She eventually died due to disease progression despite undergoing aggressive therapy. Her clinical course was thought to be more consistent with collecting duct carcinoma rather than low-grade clear cell carcinoma, which was the second component in the primary tumor. This clinical impression was further confirmed by the findings in the fine needle aspirate specimen from the lung, which was histologically identical to that seen in the primary tumor. As has been previously reported, cytotoxic chemotherapy, including the combination of paclitaxel and carboplatinum, may provide palliation in some patients with collecting duct carcinoma. However, the role of targeted therapy in this disease has not been defined.

In summary, although rare, collision tumors composed of more than one tumor type are well documented in the kidney. Tumors may occur as a combination of any of the known histologic subtypes. Careful gross examination is invaluable; close attention must be paid to areas that look grossly different to exclude the possibility of more than one tumor type existing in the same specimen, as prognosis is usually determined by the high-grade component.

References

- 1.Cho NH, Kim S, Ha MJ, et al. Simultaneous heterogenotypic renal cell carcinoma: immunohistochemical and karyoptic analysis by comparative genomic hybridization. Urol Int. 2004;72:344–348. doi: 10.1159/000077691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong Y, Sun X, Haines GK, et al. Renal cell carcinoma, chromophobe type, with collecting duct carcinoma and sarcomatoid components. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e38–e40. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e38-RCCCTW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawano N, Inayama Y, Nakaigawa N, et al. Composite distal nephron-derived renal cell carcinoma with chromophobe and collecting duct carcinomatous elements. Pathol Int. 2005;55:360–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matei DV, Rocco B, Varela R, et al. Synchronous collecting duct carcinoma and papillary renal cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roehrl MH, Selig MK, Nielsen GP, et al. A renal cell carcinoma with components of both chromophobe and papillary carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valderrama E, Kalra J, Badlani G, et al. Simultaneous renal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of kidney. Urology. 1987;29:441–445. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(87)90522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasuri F, Fellegara G. Collision renal tumors. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:338–339. doi: 10.1177/1066896908321183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagamoto A, Kijima H, Tsuchida T, et al. Collecting duct carcinoma mixed with common renal cell carcinoma: analysis of morphological characteristics using lectin histochemistry. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:567–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]