Abstract

Objective

We conducted this study to determine if the type of insurance arrangement, specifically health maintenance organization (HMO) versus fee-for-service (FFS), influences cancer outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities.

Study Design

Retrospective cohort

Methods

We used the Medicare-SEER linked dataset to identify beneficiaries older and younger than 65 entitled to Medicare due to disability (Social Security Disability Insurance) who subsequently were diagnosed with either breast (n=6,839) or non-small cell lung cancers (n=10,229) from 1988 through 1999. We categorized persons according to Medicare insurance arrangement (continuous FFS, continuous HMO, mixed HMO/FFS) during the time periods 12 months prior to diagnosis and the six month period following diagnosis. Using a retrospective cohort design, we examined stage at diagnosis, cancer directed treatments, and survival.

Results

Women with continuous HMO insurance had earlier stage breast cancer diagnosis (adjusted relative risk 0.77 [95% CI, 0.65 – 0.91]) and were more likely to receive radiation therapy following breast conserving surgery (adjusted relative risk 1.11 [1.03 – 1.19]). Women having continuous HMO insurance had better breast cancer survival primarily resulting from earlier stage diagnosis. Among persons with non-small cell lung cancer, those having mixed HMO/FFS insurance were more likely to receive definitive surgery for early stage disease (adjusted OR 1.23 [95% CI, 1.02–1.49]) and to have better overall survival, but not significantly better lung cancer survival.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that, when diagnosed with breast or non-small cell lung cancer, some Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities fare better with managed care compared with FFS insurance plans.

Introduction

In 2005, 1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries (6.5 million persons) was entitled to receive Medicare benefits due to disability.1 Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities appear to be at risk for increased cancer mortality,2 even when diagnosed at the same or earlier stage as persons without disabilities.3 In addition, persons with disabilities may receive different cancer treatment than persons without disabilities.2, 4

Medicare beneficiaries may receive care within a health maintenance organization (HMO) or within the fee-for-service (FFS) sector. It is uncertain whether the type of health insurance arrangement (HMO versus FFS) affects the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities.5 In some studies, beneficiaries with disabilities were less satisfied with managed care plan performance and were more likely to disenroll.6, 7 However, other evidence indicates that beneficiaries with disabilities receiving care in HMO plans perceive better access to primary care services and greater affordability of health services than those with traditional Medicare coverage.8 Also, Medicare beneficiaries who are enrolled in HMO plans are more likely to undergo cancer screening,9–12 more likely to have cancers diagnosed at an earlier stage,13–16, and may have improved survival.14

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries merged with Medicare data have been used to study health disparities among persons with disabilities.2, 3 We used merged SEER-Medicare data to evaluate whether the type of Medicare insurance arrangement (either HMO or FFS) affects cancer outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities. We studied two high volume cancers; lung cancer and breast cancer. We chose breast cancer because it is amenable to screening, and experiences of these patients would capture potential disparities in early detection as well as treatment. In contrast, screening is not currently recommended to detect lung cancer, although surgical and radiation treatment may improve survival.17, 18

Methods

Data Sources

We used the Medicare-SEER dataset which links SEER registry information to Medicare claims data.19, 20 SEER consists of 11 population-based tumor registries, representing approximately 14% of the US population.20 SEER collects patient information on demographic characteristics, primary tumor site, stage at diagnosis, tumor size, histology, tumor grade, hormone receptor status, initial course of treatment, and vital status. SEER tracks vital status annually and death certificates are used to capture underlying cause of death.

Study Sample

We identified all persons 21 years and older within the Medicare-SEER dataset having a pathologically confirmed first diagnosis of either breast (n=62,315) or non-small cell lung cancer (n=55,770) during the period January 1, 1988 through December 31, 1999. We then restricted our sample to those persons who originally qualified for Medicare coverage because of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) (breast n=6,839, lung n=10,229). Our sample thus includes persons younger than 65 who have SSDI and persons 65 and older whose SSDI has been automatically converted to Old Age Survivors Insurance. As described elsewhere, we focused exclusively on individuals with Medicare when newly diagnosed with cancer, thus eliminating persons disabled by cancer.3

Medicare data indicate for each month whether persons were eligible for Part A and Part B and whether they were enrolled in an HMO insurance arrangement. To examine possible impacts of insurance structure on early detection of cancer, we constructed a variable that defined insurance arrangement prior to diagnosis. We determined the type of insurance arrangement during the month of diagnosis and the previous 12 months. During this time period, we assigned cases to one of three insurance categories: FFS for persons continuously enrolled in traditional FFS Medicare; HMO for persons continuously enrolled in HMO plans; and mixed FFS/HMO, for persons enrolled in both FFS and HMO plans during this period. To examine treatments following diagnosis we designated similar post-diagnosis insurance variables for persons continuously eligible for Medicare Part A and Part B during the month of diagnosis and the six months following diagnosis (or until death if survival was less than six months). For analyses of survival, we assigned cases to similar insurance categories covering the pre- and post-diagnosis periods combined.

Stage at Diagnosis

SEER determines stage at diagnosis based on a combination of pathologic surgical and clinical assessments available within 2 months of diagnosis.21 Stage at diagnosis is recorded using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system (0, I, II, III, IV). In our analysis of stage at diagnosis, we excluded persons whose cancers were unstaged (breast n=346, lung n=1,182).

Cancer-Directed Treatments

SEER collects information on the initial course of treatment, which was defined as all cancer-directed treatments within 4 months of diagnosis from 1973–1998 and within 12 months of diagnosis after 1998. Ascertainment of surgery and radiation therapy by SEER is generally complete.22, 23 Ascertainment of chemotherapy, however, is not complete and is not included in the Medicare-SEER linked dataset. SEER does not collect information on pre-diagnosis screening tests, like mammograms. We relied solely on SEER information to define cancer-directed treatments as Medicare claims are not available for persons having HMO insurance.

We defined breast conserving surgery as segmental mastectomy, lumpectomy, quadrantectomy, tylectomy, wedge resection, nipple resection, excisional biopsy, or partial mastectomy that was not otherwise specified. We defined mastectomy as subcutaneous, total (simple), modified radical, radical, extended radical mastectomy, or mastectomy that was not otherwise specified. We examined frequency of breast conserving surgery among women having AJCC stage I, II, or IIIA cancers. We further examined two secondary outcomes related to quality of care; receipt of axillary lymph node dissection and receipt of radiation therapy among women who undergo breast conserving surgery. Sentinel lymph node biopsies, a relatively recent innovation, are not reported in our database.

Depending on tumor size, histology, and location, surgery can provide definitive treatment for non-small cell lung cancer.17, 18 Radiotherapy may also be curative for persons with resectable tumors who do not undergo surgery.24, 25 We examined the frequencies of surgical resection and radiotherapy among persons having early stage lesions (AJCC stage I) for whom treatment can be curative. Similar to Bach and colleagues,26 we identified surgical resection with curative intent as follows: radical or partial pneumonectomy, lobectomy, bilobectomy, sleeve resection, segmentectomy, wedge resection, and local resection. For persons who did not undergo surgery, we used SEER data to determine if surgery was contraindicated or not recommended.

Survival

We examined survival (all cause and cancer-specific mortality) following diagnosis. We measured survival time as the number of days from diagnosis until death or December 31, 2001, whichever came first. For all cause mortality analyses, we censored observations of persons alive at the end of follow-up. We also studied breast and lung cancer-specific deaths, censoring observations of subjects alive at the end of follow-up or who died from causes other than breast or lung cancer.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted bivariable analyses to compare demographic and tumor characteristics of our study sample by HMO versus FFS status at diagnosis. Because this was an observational study, which did not randomize subjects to HMO versus FFS insurance, patient characteristics were expected to differ between the two groups. We used the method of propensity scores to control for these differences.27, 28

Propensity scores reflect the likelihood that a patient had HMO insurance at diagnosis based on his or her observed characteristics. We used multivariable logistic regression with stepwise variable selection to calculate propensity scores (done separately for breast and lung cancer patients). Having HMO insurance at diagnosis was the outcome with the following variables as potential predictors: age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, marital status at diagnosis, census-derived measures of median household income and percentage of households without high school education, SEER tumor registry, year of diagnosis, and tumor characteristics (grade, histology, presence of hormonal receptors). We then used propensity scores to group patients into quintiles according to their probability of having HMO insurance at diagnosis, derived from observed characteristics. We then added propensity scores (quintiles) as a covariate in all multivariable analyses. This process has been estimated to eliminate more than 90% of the bias resulting from differences in observed covariates.29

We conducted multivariable polychotomous logistic regression to examine associations between HMO versus FFS insurance arrangement and AJCC stage at diagnosis (0, I, II, III, and IV). Odds ratios less than one indicate earlier stage at diagnosis. Logistic models adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian American/Pacific Islander, other), marital status at diagnosis (married, widowed, never married, other), census-derived measures of median household income and percentage of households without high school education, SEER tumor registry, year of diagnosis, grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly/undifferentiated), as well as propensity scores. For persons with lung cancer, logistic models also adjusted for gender. For women with breast cancer, logistic models also adjusted for histology (ductal, lobular/mixed favorable subtypes [papillary, villous, or mucinous adenocarcinomas, medullary carcinoma], unfavorable subtypes [inflammatory, Pagets]), estrogen receptor status (positive, negative, unknown) and progesterone receptor states (positive, negative, unknown). We converted odds ratios to relative risks with 95% confidence intervals for each treatment outcome.30

We plotted survival curves for all cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality separately. Survival differences between subjects having HMO versus FFS insurance were tested using the log rank test. We excluded persons with in situ cancers from survival analyses.

We conducted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate adjusted relative hazard ratios for each mortality outcome (all cause and cancer-specific). Hazard rates less than one indicate lower mortality and more favorable survival relative to the referent group. We fit two sets of proportional hazards models for each mortality outcome. In the initial models, hazard rates were adjusted for age, gender (for lung cancer only), marital status (married, single, separated/divorced, widowed, unknown), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, other), census-derived measures of median household income and percentage of households without high school education, tumor grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, undifferentiated, unknown), and propensity scores. For women with breast cancer, initial models also adjusted hazard rates for estrogen receptor status (negative, positive, unknown), progesterone status (negative, positive, unknown), and histology (ductal, lobular/mixed, favorable subtypes, unfavorable subtypes, other). Subsequent models also adjusted hazard rates for AJCC stage at diagnosis (I, II, III, IV, unstaged).

As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated multivariable models excluding patients with missing data on tumor characteristics (tumor grade, estrogen and progesterone receptor status). To gauge the public health impact of our findings we calculated attributable fractions using the formula: attributable fraction = pd (RR − 1) / RR, where pd = the proportion of cases exposed to the risk factor and RR = the adjusted hazard rate.31 The institutional review board at our institutions approved this study. All statistical analyses used SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 describes the characteristics of our sample. Persons having HMO insurance at diagnosis tended to be older and more likely to reside in census tracts having higher median household income. Consistent with market penetration of HMOs, patients having HMO insurance were more likely to originate from SEER registries in California and Seattle. Among patients with breast cancer, those having FFS insurance were more likely to have missing information on tumor grade and on estrogen and progesterone receptor status.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Insurance Status

| Characteristic | Insurance Type at Time of Breast Cancer Diagnosis |

Insurance Type at Time of Lung Cancer Diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMO n = 878 |

FFS n = 5,316 |

P-value | HMO n = 1,491 |

FFS n = 7,896 |

P-value | |

| Mean age (years) | 63.9 | 61.4 | <0.0001 | 66.9 | 64.4 | <0.0001 |

| Age (%) | ||||||

| < 60 | 24.0 | 35.9 | <0.0001 | 10.4 | 21.9 | <0.0001 |

| 60–64 | 21.1 | 19.2 | 18.3 | 22.7 | ||

| 65–69 | 29.4 | 22.6 | 35.5 | 29.0 | ||

| 70+ | 25.5 | 22.3 | 35.7 | 26.4 | ||

| Gender (%) | ||||||

| Female | 29.2 | 28.0 | 0.35 | |||

| Male | 70.8 | 72.0 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.8 | 69.2 | <0.0001 | 72.8 | 74.8 | <0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 14.9 | 20.0 | 15.8 | 19.3 | ||

| Hispanic | 10.1 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 3.5 | ||

| Asian | 5.1 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.0 | ||

| Other | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | ||

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Married | 42.1 | 29.2 | <0.0001 | 55.3 | 49.3 | <0.0001 |

| Single | 11.9 | 24.2 | 10.8 | 14.6 | ||

| Separated/divorced | 18.5 | 18.2 | 15.0 | 17.0 | ||

| Widowed | 24.5 | 24.8 | 16.3 | 15.6 | ||

| Unknown | 3.1 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.6 | ||

| Census-derived median household income (dollars) | 36,573 | 32,488 | <0.0001 | 34,210 | 31,361 | <0.0001 |

| Percent of Zip-Code/Census Tract without High School Education | 22.9 | 25.3 | <0.0001 | 26.1 | 26.2 | 0.84 |

| Registry Site (%) | ||||||

| San Francisco/Oakland | 22.4 | 11.1 | <0.0001 | 20.4 | 10.4 | <0.0001 |

| Connecticut | 4.1 | 12.9 | 4.8 | 12.6 | ||

| Detroit | 4.6 | 19.8 | 10.4 | 22.3 | ||

| Hawaii | 3.5 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 2.0 | ||

| Iowa | 2.6 | 10.3 | 4.1 | 13.7 | ||

| New Mexico | 4.4 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 4.0 | ||

| Seattle | 14.4 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 11.8 | ||

| Utah | 1.7 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 2.3 | ||

| Atlanta | 2.9 | 7.6 | 1.5 | 8.8 | ||

| San Jose/Monterey | 5.5 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.2 | ||

| Los Angeles | 33.9 | 14.0 | 33.1 | 9.9 | ||

| AJCC Stage (%) | ||||||

| In situ | 13.8 | 12.3 | <0.0001 | |||

| Stage I | 46.1 | 37.6 | 23.8 | 23.9 | 0.30 | |

| Stage II | 29.3 | 32.9 | 4.7 | 4.4 | ||

| Stage III | 4.9 | 7.0 | 28.3 | 28.6 | ||

| Stage IV | 3.0 | 4.7 | 30.0 | 31.8 | ||

| Unstaged / unknown | 3.0 | 5.6 | 13.2 | 11.4 | ||

| Tumor Grade (%) | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 16.6 | 11.4 | <0.0001 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 0.34 |

| Moderately differentiated | 30.0 | 27.7 | 16.3 | 17.2 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 27.2 | 24.7 | 38.2 | 35.4 | ||

| Undifferentiated | 3.1 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 6.9 | ||

| Unknown | 23.1 | 33.7 | 35.2 | 36.6 | ||

| Histology (%) | ||||||

| Ductal | 73.1 | 76.4 | 0.25 | |||

| Lobular / mixed | 13.4 | 11.8 | ||||

| Favorable subtypes* | 7.4 | 6.2 | ||||

| Unfavorable subtypes** | 2.5 | 2.1 | ||||

| Other | 3.5 | 3.6 | ||||

| ER status (%) | ||||||

| Positive | 61.6 | 52.4 | <0.0001 | |||

| Negative | 17.2 | 16.6 | ||||

| Unknown | 21.2 | 31.0 | ||||

| PR status (%) | ||||||

| Positive | 48.6 | 44.5 | <0.0001 | |||

| Negative | 26.0 | 22.7 | ||||

| Unknown | 25.4 | 32.8 | ||||

Favorable subtypes include papillary, mucinous, tubular and medullary.

Unfavorable subtypes include inflammatory and Pagets

Table 2 describes the likelihood of earlier stage at diagnosis according to insurance arrangement during the one year time period prior to diagnosis. For women with breast cancer, those having HMO insurance were diagnosed at earlier stages relative to women having FFS insurance. There also was some evidence of earlier stage at diagnosis for women with mixed HMO/FFS insurance, i.e. the odds ratio was significant in the unadjusted model but not in the model that controlled for age, race, and other covariates. HMO versus FFS insurance was not associated with stage at diagnosis for persons with lung cancer.

Table 2.

Likelihood of Earlier Stage at Diagnosis According to Insurance Status*

| Insurance Type** | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer (n = 5,446) | ||

| FFS (n = 4,924) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO (n = 664) | 0.73 (0.63 – 0.85) | 0.77 (0.65 – 0.91) |

| Mixed FFS/HMO (n=184) | 0.73 (0.56 – 0.96) | 0.78 (0.59 – 1.04) |

| Lung cancer (n = 7,804) | ||

| FFS (n=6,758) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO (n=811) | 0.97 (0.85 – 1.11) | 0.96 (0.83 – 1.11) |

| Mixed FFS/HMO (n=235) | 1.02 (0.81 – 1.30) | 1.01 (0.79 – 1.29) |

Results of polychotomous logistic regression examining AJCC stage (0, I, II, III, IV) at diagnosis.

Insurance status during month of diagnosis and 12 month period prior to month of diagnosis (FFS=fee-for-service, HMO=Health Maintenance Organization)

Outcomes in bold are significant at p<0.05

Insurance type was sometimes significantly associated with cancer directed treatments for both breast and lung cancer (Table 3). Women having HMO insurance were more likely to receive radiation therapy following breast conserving surgery. There was also a statistically non-significant trend for women having HMO insurance to receive breast conserving surgery rather than mastectomy. Insurance status had no effect on likelihood of axillary lymph node dissection. Among persons diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer, those having mixed HMO / FFS insurance were more likely to receive definitive surgery for early stage tumors.

Table 3.

Cancer Treatments by Insurance Status†

| Insurance | Percentage | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | |||

| Receipt of Breast Conserving Surgery* | |||

| FFS | 40.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 47.2 | 1.33 (1.13 – 1.58) | 0.97 (0.87 – 1.07) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 44.9 | 1.22 (0.75 – 1.96) | 1.04 (0.80 – 1.34) |

| Receipt of Radiation Therapy after Breast Conserving Surgery** | |||

| FFS | 70.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 79.4 | 1.60 (1.18 – 2.16) | 1.11 (1.03 – 1.19) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 83.3 | 2.07 (0.79 – 5.45) | 1.21 (1.06 – 1.39) |

| Receipt of Lymph Node Dissection*** | |||

| FFS | 86.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 85.0 | 0.91 (0.72 – 1.15) | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.04) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 87.0 | 1.07 (0.53 – 2.17) | 1.01 (0.92 – 1.11) |

| Lung Cancer | |||

| Receipt of Surgery**** | |||

| FFS | 63.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 69.3 | 1.10 (1.01 – 1.20) | 1.06 (0.97 – 1.16) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 80.0 | 1.27 (1.04 – 1.54) | 1.23 (1.02 – 1.49) |

| Receipt of Radiation Therapy***** | |||

| FFS | 28.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 22.9 | 0.79 (0.63 – 1.00) | 0.93 (0.77 – 1.12) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 20.0 | 0.69 (0.31 – 1.53) | 1.11 (0.66 – 1.84) |

| Receipt of Surgery or Radiation Therapy***** | |||

| FFS | 88.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 88.8 | 1.00 (0.96 – 1.05) | 1.00 (0.95 – 1.05) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 96.0 | 1.09 (1.00 – 1.18) | 1.09 (1.02 – 1.17) |

Insurance status during period including month of diagnosis and 6 months following month of diagnosis.

Among women having AJCC stage I or II, or IIIA lesions, and undergoing either BCS or mastectomy (n=4,480)

Among women having AJCC stage I or II, or IIIA lesions, and undergoing breast conserving surgery (n=1,775)

Among women having AJCC stage I or II, or IIIA lesions (n=4,480)

Among persons having AJCC stage I cancers (n=2,240)

Among persons having AJCC stage I cancers (n=2,240). Adjusted models also controlled for concomitant use of lung cancer surgery.

Outcomes in bold are significant at p<0.05

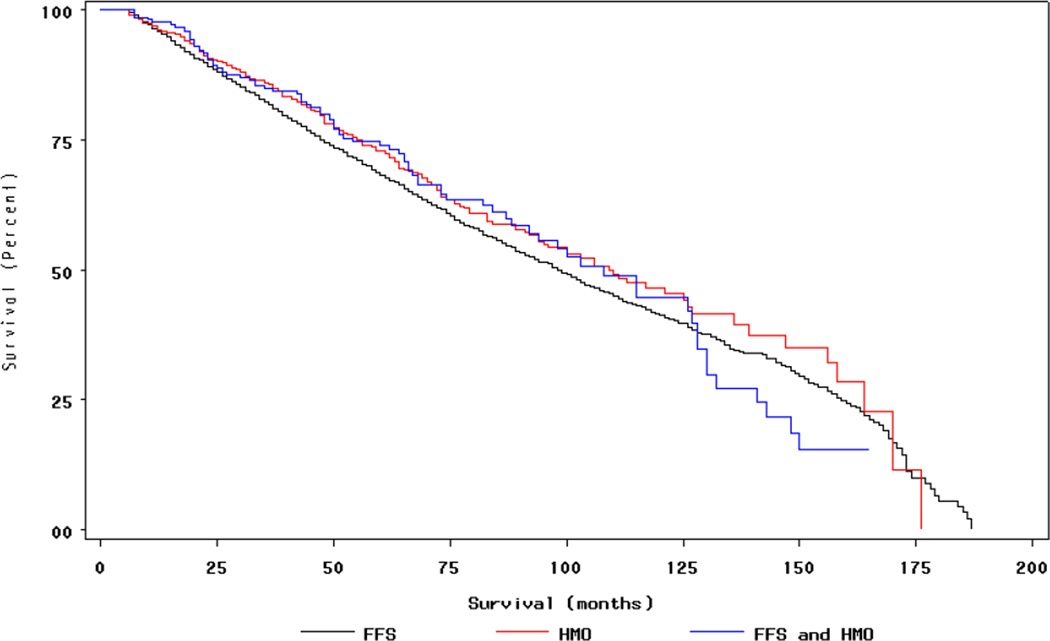

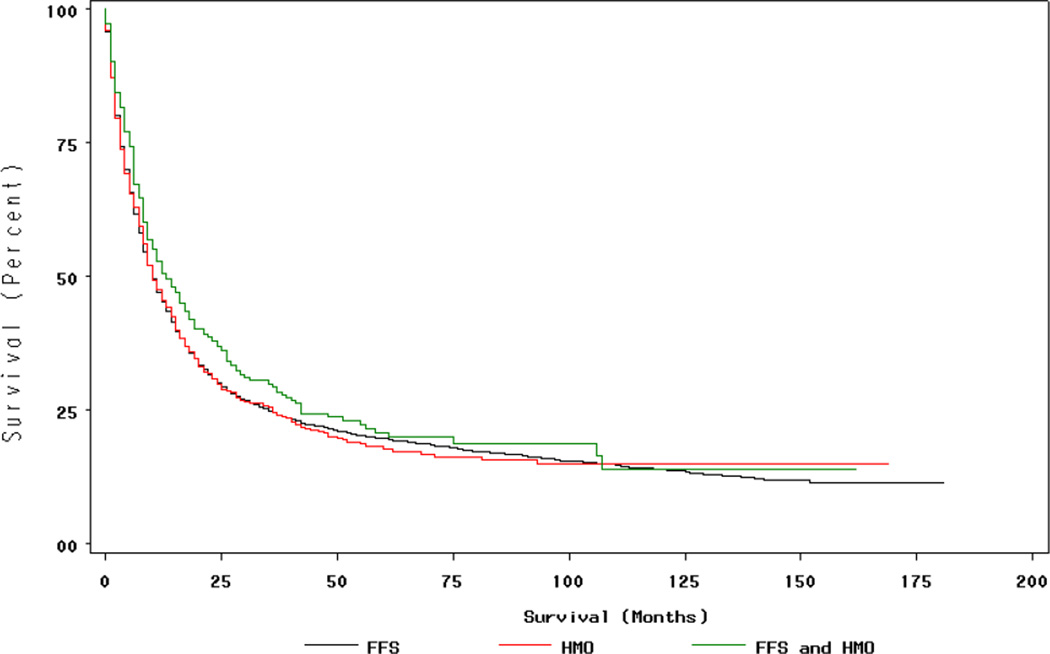

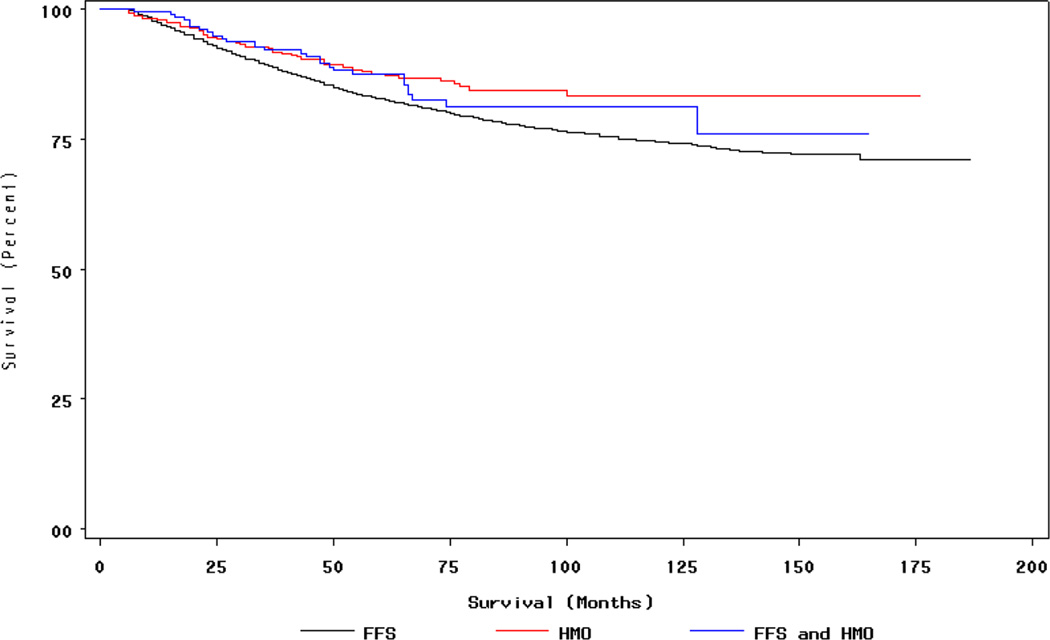

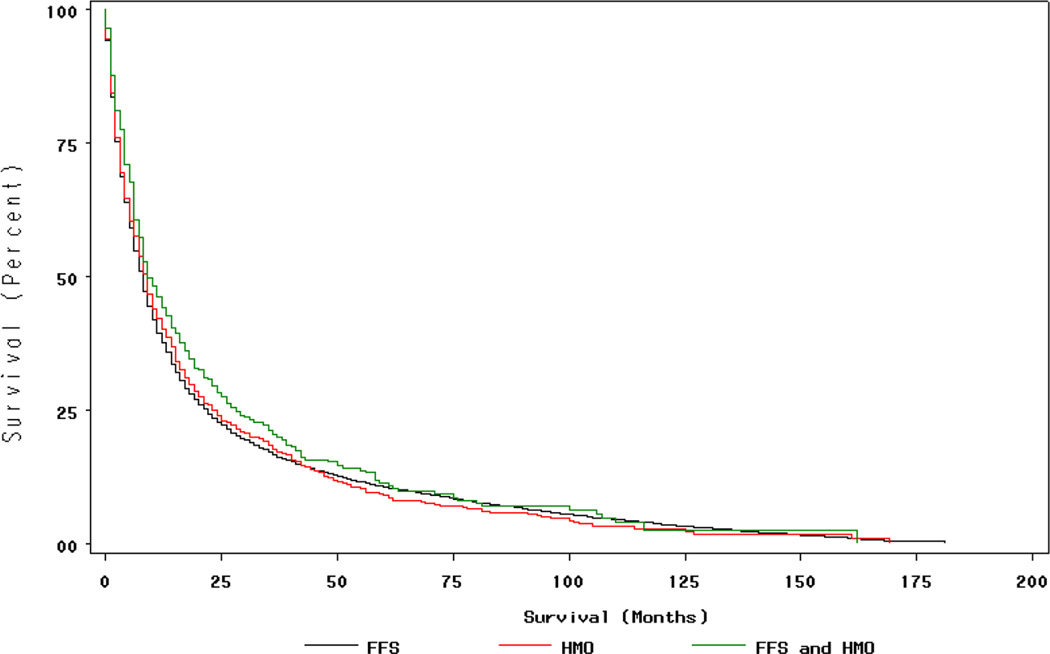

Figures 1 through 4 (available on website) display all cause and cancer-specific survival curves. Among women with breast cancer, women having HMO insurance had better breast cancer survival compared to women having continuous FFS insurance. Among persons with lung cancer, there was a statistically non-significant trend for improved survival among persons having mixed HMO/FFS insurance.

Figure 1. Survival (all causes) by Insurance Type for Women with Breast Cancer†.

†Insurance status during period during 12 months prior to month of diagnosis, month of diagnosis, and six months following month of diagnosis (FFS n=4,118, HMO n=542, Mixed HMO/FFS n=217) Women with in situ cancers excluded.

Figure 4. Lung Cancer Survival by Insurance Type.

†Insurance status during period during 12 months prior to month of diagnosis, month of diagnosis, and six months following month of diagnosis (FFS n=7,568 HMO n=916, Mixed HMO/FFS n=350) Persons with in situ cancers excluded. P=0.09 for differences in survival by Log-Rank test.

Breast cancer mortality rates were lower for women having HMO insurance (Table 4). Lower breast cancer mortality rates persisted after adjustment for patient and tumor characteristics but were no longer present after further adjustment for stage at diagnosis. Among non-small cell lung cancer patients, those with mixed HMO/FFS insurance had better overall survival (with trends toward better lung cancer survival) in both unadjusted analysis and analysis adjusted for covariates.

Table 4.

Mortality Rates by Insurance Status†

| Insurance | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Stage-adjusted HR (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (n = 4,877) | |||

| All Cause Mortality | |||

| FFS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 0.87 (0.75 – 1.01) | 0.81 (0.69 – 0.95) | 0.91 (0.78 – 1.07) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 0.94 (0.76 – 1.17) | 0.92 (0.74 – 1.15) | 0.97 (0.78 – 1.21) |

| Breast Cancer Mortality | |||

| FFS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 0.67 (0.52 – 0.87) | 0.75 (0.57 – 0.98) | 0.97 (0.73 – 1.27) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 0.77 (0.54 – 1.11) | 0.88 (0.61 – 1.28) | 0.97 (0.67 – 1.41) |

| Lung Cancer (n = 8,834) | |||

| All Cause Mortality | |||

| FFS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 0.99 (0.92 – 1.06) | 0.95 (0.88 – 1.03) | 0.97 (0.90 – 1.05) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 0.88 (0.79 – 0.99) | 0.89 (0.79 – 0.996) | 0.87 (0.78 – 0.98) |

| Lung Cancer Mortality | |||

| FFS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HMO | 1.01 (0.93 – 1.09) | 0.99 (0.91 – 1.09) | 1.01 (0.93 – 1.11) |

| Mixed HMO/FFS | 0.87 (0.77 – 0.99) | 0.89 (0.78 – 1.02) | 0.88 (0.77 – 1.01) |

Insurance status during period 12 months prior to month of diagnosis, month of diagnosis, and six months following month of diagnosis for subjects with breast cancer (FFS n=4,118, HMO n=542, Mixed HMO/FFS n=217) and with non-small cell lung cancer (FFS n=7,568, HMO n=916, Mixed HMO/FFS n=350).

Stage-adjusted hazard rates also adjusted for AJCC stage (I, II, III, IV, unstaged). Persons with in situ cancers excluded.

Outcomes in bold are significant at p<0.05

Results presented above were similar when subjects having missing information on tumor characteristics were excluded from the sample and multivariable analysis repeated (data not presented). To examine the possibility that the effects of HMO insurance varied over time, we also repeated our analyses separately for two time periods, persons who were diagnosed from 1989 –1994, and persons diagnosed 1995 through 1999. Results were similar for both time periods. We calculated an attributable fraction for the 831 breast cancer deaths observed in the cohort (FFS insurance n=769, HMO insurance n=62). We estimated that 17% (144 deaths) would theoretically have been prevented if patients having FFS insurance had a mortality experience comparable to HMO patients instead.

Discussion

Insurance type (FFS versus HMO) sometimes was significantly associated with treatment outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities diagnosed with breast or lung cancers. Patients with disabilities having HMO insurance coverage were more likely to be diagnosed with earlier stage breast cancer and were more likely to undergo radiation therapy after breast conserving surgery. HMO insurance coverage was also associated with longer breast cancer survival due primarily to earlier stage diagnosis. Insurance status had fewer significant associations for patients with disabilities diagnosed with lung cancer (no association with stage for example).

Among Medicare beneficiaries, patients belonging to HMOs are more likely screened for cancer,9–12 and are more likely to have cancers diagnosed at an earlier stage.13–16 This may in part explain our finding of earlier breast cancer diagnosis and improved survival. Higher rates of cancer screening within HMOs may result from greater emphasis on delivering preventive care32 and having greater focus on primary care rather than subspecialty care.33 In some studies, beneficiaries with disabilities in HMOs perceived better access to primary care services,8 and were more likely to undergo cancer screening tests.34 Greater use of preventive services in HMOs may also be the result in part of favorable selection, in which healthier patients are differentially enrolled in HMOs.35

There was some evidence that Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities enrolled in HMOs were more frequently treated with breast conserving surgery, as shown by a significant odds ratio in the unadjusted model, but not the adjusted model. These HMO enrollees also were more often treated with radiation therapy following breast conserving surgery (the treatment combination recommended by NIH consensus panels) and had better breast cancer survival. Persons having HMO insurance were also more likely to have tumor grade and hormone receptor status documented for their cancers. Previous studies have also suggested that in general, Medicare beneficiaries belonging to HMOs are more likely to undergo breast conserving surgery,36 to receive adjuvant radiation therapy following breast conserving surgery,16 and to have improved breast cancer survival.36, 37 Our study extends these findings to Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities.

The reasons for treatment differences among patients having HMO versus FFS insurance could not be ascertained in this study but could result from differences in practice structure. HMOs, especially staff and group model forms, have resources and organizational structures that can disseminate standards of care and ensure that current practice patterns are consistent with these standards.38, 39 Improved breast cancer survival among HMO recipients appeared to be primarily the result of earlier stage at diagnosis

While HMO versus FFS insurance arrangement was significantly associated with breast cancer outcomes, lung cancer outcomes showed few effects. The subset of persons changing between HMO/FFS plans appeared to have better lung cancer outcomes. Among the 137 patients with lung cancer who changed insurance type between diagnosis and six months follow-up, most (65.0%) changed from HMO to FFS insurance. This group had greater likelihood of receiving surgery for early stage disease and had better overall survival with a statistically non-significant trend towards better lung cancer survival.

Changing between HMO and FFS Medicare plans might indicate problems accessing care or dissatisfaction with care. Patients with disabilities are generally more likely to report dissatisfaction or problems with their health care plan6, 7, 40–42 and are more likely to disenroll from their HMO, often changing to a FFS plan.43 Forced disenrollment from a Medicare HMO plan has also been associated with problems accessing needed care.44–46

In our study, Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities had remarkably stable HMO/FFS insurance status during the course of their follow-up, similar to other reported studies.47, 48 Among persons continuously eligible for Medicare and followed until their death, 95.2% of persons with lung cancer and 92.3% of persons with breast cancer had continuous coverage within FFS or HMO arrangements from the year prior to diagnosis until their death. In addition, patients who changed between FFS and HMO plans generally had similar or better outcomes compared to persons continuously enrolled in FFS.

Our study had several important limitations. First, we did not have Medicare claims data for persons enrolled in HMOs and were thus not able to examine cancer screening or to supplement SEER information on treatment using Medicare claims. Our lack of Medicare claims for persons in HMOs also prevented us from assessing comorbidity. SEER does not release data on chemotherapy so we were unable to assess this aspect of cancer treatment, which is especially critical in breast cancer. Medicare data did not include details about the specific HMO plan so were unable to assess the particular financial arrangements for the HMO plan nor could we capture patient movement between HMO plans. Our sample was restricted to persons who originally qualified for Medicare coverage because of SSDI, and our results may not generalize to the greater population of persons with disability. We studied persons who were diagnosed with cancer through the end of 1999 and it is possible that trends may have changed since that time. Finally, this was an observational study that did not randomize subjects to insurance types. Statistical methods, such as propensity scores, can only adjust for measured characteristics within the cohort. As a result it is possible that our results were in part due to unmeasured patient characteristics that differed between HMO and FFS patients and not due to the specific insurance arrangement.

In conclusion, Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities diagnosed with breast cancer generally had more favorable outcomes within HMO arrangements. HMO versus FFS insurance status had little impact on lung cancer outcomes. Changes between HMO and FFS insurance arrangements were not associated with poor cancer outcomes.

Figure 2. Breast Cancer Survival by Insurance Type.

†Insurance status during period during 12 months prior to month of diagnosis, month of diagnosis, and six months following month of diagnosis (FFS n=4,118, HMO n=542, Mixed HMO/FFS n=217) Women with in situ cancers excluded.

Figure 3. Survival (all causes) by Insurance Type for Persons with Lung Cancer†.

†Insurance status during period during 12 months prior to month of diagnosis, month of diagnosis, and six months following month of diagnosis (FFS n=7,568 HMO n=916, Mixed HMO/FFS n=350) Persons with in situ cancers excluded. P=0.08 for differences in survival by Log-Rank test.

Acknowledgment

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of several groups responsible for the creation and dissemination of the Linked Database, including the Applied Research Branch, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Information Services, and the Office of Strategic Planning, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Tumor Registries.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Enrollment - Disabled Beneficiaries: as of July 2005. [Accessed January 21, 2008]; http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareEnRpts/Downloads/05Disabled.pdf.

- 2.McCarthy EP, Ngo LH, Roetzheim RG, et al. Disparities in breast cancer treatment and survival for women with disabilities. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(9):637–645. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-9-200611070-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy EP, Long HN, Chirikos TN, et al. Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Survival Among Persons with Social Security Disability Insurance on Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:611–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caban ME, Nosek MA, Graves D, Esteva FJ, McNeese M. Breast carcinoma treatment received by women with disabilities compared with women without disabilities. Cancer. 2002;94(5):1391–1396. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanenbaum S, Hurley R. Disability and managed care frenzy: A cautionary note. Health Affairs. 1995;14:213–219. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mobley L, McCormack L, Booske B, et al. Voluntary disenrollment from Medicare managed care: Market factors and disabled beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26:45–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robins C, Heller A, Myers M. Financial vulnerability among Medicare managed care enrollees. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26:81–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beatty PW, Dhont KR. Medicare health maintenance organizations and traditional coverage: perceptions of health care among beneficiaries with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1009–1017. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.25135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker LC, Phillips KA, Haas JS, Liang SY, Sonneborn D. The effect of area HMO market share on cancer screening. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1751–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrasquillo O, Lantigua RA, Shea S. Preventive services among Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental coverage versus HMO enrollees, Medicaid recipients, and elders with no additional coverage. Med Care. 2001;39(6):616–626. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon NP, Rundall TG, Parker L. Type of health care coverage and the likelihood of being screened for cancer. Med Care. 1998;36(5):636–645. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potosky A, Breen N, Graubard B, Parsons P. The association between health care coverage and the use of cancer screening tests: results from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 1998;36:257–270. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee-Feldstein A, Feldstein PJ, Buchmueller T, Katterhagen G. Breast cancer outcomes among older women: HMO, fee-for-service, and delivery system comparisons. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(3):189–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.91112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee-Feldstein A, Feldstein PJ, Buchmueller T. Health care factors related to stage at diagnosis and survival among Medicare patients with colorectal cancer. Med Care. 2002;40(5):362–374. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley G, Potosky A, Lubitz J, Brown M. Stage of cancer at diagnosis for Medicare HMO and fee-for-service enrollees. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1598–1604. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riley GF, Potosky AL, Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Ballard-Barbash R. Stage at diagnosis and treatment patterns among older women with breast cancer: an HMO and fee-for-service comparison. JAMA. 1999;281(8):720–726. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.8.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology v.2.2006. [Accessed January 21, 2008];Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, 2006. 2006 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manser R, Wright G, Hart D, Byrnes G, Campbell D. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;1:CD004699. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004699.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31(8):732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warren J, Klabunde C, Schrag D, Bach P, Riley G. Overview of the SEER-Medicare Data: Content, Research Applications, and Generalizability to the United States Elderly Population. Med Care. 2002 Aug;40(8 Suppl):3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shambaugh E, Weiss M. Summary Staging Guide: Cancer Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Reporting. Bethesda, MD: US Dept. of Health Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 1977. Vol. Publication No. 86–2313. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper GS, Virnig B, Klabunde CN, Schussler N, Freeman J, Warren JL. Use of SEER-Medicare data for measuring cancer surgery. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):43–48. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virnig BA, Warren JL, Cooper GS, Klabunde CN, Schussler N, Freeman J. Studying radiation therapy using SEER-Medicare-linked data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):49–54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowell N, Williams C. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD002935. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowell N, Williams C. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Thorax. 2001;56:628–638. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.8.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, Begg CB. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 1999;341(16):1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J. Amer Stat Assoc. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8 Pt 2):757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cochran WG. The effectiveness of adjustment by subclassification in removing bias in observational studies. Biometrics. 1968;24(2):295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flanders W, Rhodes P. Large sample confidence intervals for regression standardized risks, risk ratios, and risk differences. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:697–704. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(1):15–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Bernard SL, Cioffi MJ, Cleary PD. Comparison of performance of traditional Medicare vs Medicare managed care. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1744–1752. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips KA, Haas JS, Liang SY, et al. Are gatekeeper requirements associated with cancer screening utilization? Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):153–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan L, Doctor JN, MacLehose RF, et al. Do Medicare patients with disabilities receive preventive services? A population-based study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(6):642–646. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan R, Virnig B, DeVito C, Persily N. The Medicare-HMO revolving door: The healthy go in and the sick go out. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:169–175. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707173370306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potosky AL, Merrill RM, Riley GF, et al. Breast cancer survival and treatment in health maintenance organization and fee-for-service settings. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89(22):1683–1691. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.22.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirsner RS, Ma F, Fleming L, et al. The effect of medicare health care delivery systems on survival for patients with breast and colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):769–773. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clancy C, Brody H. Managed care: Jekyll or Hyde? JAMA. 1995;273:338–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner E, Austin B, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jha A, Patrick DL, MacLehose RF, Doctor JN, Chan L. Dissatisfaction with medical services among Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(10):1335–1341. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, Soukup J, O'Day B. Satisfaction with quality and access to health care among people with disabling conditions. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(5):369–381. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gold M, Nelson L, Brown R, Ciemnecki A, Aizer A, Docteur E. Disabled Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs. Health Aff. 1997;16(5):149–162. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.5.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laschober M. Estimating Medicare Advantage lock-in provisions impact on vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26:63–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schoenman J, Parente S, Feldman J, Shah M, Evans W, Finch M. Impact of HMO withdrawals on vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26:5–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parente S, Evans W, Schoenman J, Finch M. Health care use and expenditures of Medicare HMO disenrollees. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26:31–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Booske BC, Lynch J, Riley G. Impact of Medicare managed care market withdrawal on beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 2002;24(1):95–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Field TS, Cernieux J, Buist D, et al. Retention of enrollees following a cancer diagnosis within health maintenance organizations in the Cancer Research Network. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(2):148–152. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riley GF, Feuer EJ, Lubitz JD. Disenrollment of Medicare cancer patients from health maintenance organizations. Med Care. 1996;34(8):826–836. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199608000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]