Abstract

CD1d-restricted NKT cells can be divided into two groups: type I NKT cells utilize a semi-invariant TCR whereas type II express a relatively diverse set of TCRs. A major subset of type II NKT cells recognizes myelin-derived sulfatides and is selectively enriched in the central nervous system tissue during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). We have shown that activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells by sulfatide prevents induction of EAE. Here we have addressed the mechanism of regulation as well as whether a single immunodominant form of synthetic sulfatide can treat ongoing chronic and relapsing EAE in SJL/J mice. We have shown that the activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells leads to a significant reduction in the frequency and effector function of PLP139-151/I-As–tetramer+ cells in lymphoid and CNS tissues. In addition, type I NKT cells and dendritic cells in the periphery as well as CNS-resident microglia are inactivated following sulfatide administration, and mice deficient in type I NKT cells are not protected from disease. Moreover tolerized DCs from sulfatide-treated animals can adoptively transfer protection into naive mice. Treatment of SJL/J mice with a synthetic cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide, but not αGalCer, reverses ongoing chronic and relapsing EAE. Our data highlight a novel immune regulatory pathway involving NKT subset interactions leading to inactivation of type I NKT cells, DCs, and microglial cells in suppression of autoimmunity. Since CD1 molecules are non-polymorphic, the sulfatide-mediated immune regulatory pathway can be targeted for development of non-HLA-dependent therapeutic approaches to T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases.

Introduction

Natural killer T cells (NKT) that share the cell surface receptors of NK cells (for example, NK1.1) and in addition express an antigen receptor (TCR) generally recognize lipid antigens in the context of the CD1 molecules and bridge innate immune responses to adaptive immunity (1, 2). Their activation can influence the outcome of the immune response against tumors and infectious organisms and in addition can modulate the course of several autoimmune diseases in experimental animal models and potentially in humans (3-7). Therefore characterization of the biology and function of NKT cells is important for understanding their role in the entire spectrum of immune responses. CD1 molecules are non-polymorphic, MHC class I-like, and associated with β2-microglobulin and are expressed on antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages, and subsets of B cells (1, 2). The CD1d pathway is highly conserved and is present in both mice and in humans.

Based upon their TCR gene usage CD1d-restricted NKT cells can be divided into 2 categories: one using a semi-invariant TCR (iNK T or type I) and the other expressing somewhat more diverse TCRs (type II NKT) (1, 4, 5, 8). The invariant receptor on type I NKT cells is encoded by the germ line TCR α chain (mouse Vα14Jα18, human Vα24-JαQ) and diverse TCR Vβ chains (mouse predominantly Vβ8, human predominantly Vβ11). Type I NKT cells in mice and in humans can recognize α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), a marine sponge-derived glycolipid, and self-glycolipids such as iGB3 and βGlcCer. A major subset of type II NKT cells has been shown to recognize a self-glycolipid sulfatide (3’-sulfogalactosyl ceramide) in both mice and in humans (9-13). Type I NKT can be identified using αGalCer/CD1d-tetramers, whereas a major subset of type II NKT cells can be identified using sulfatide/CD1d-tetramers. Since type I NKT cells use the invariant Vα14-Jα18 TCR, mice deficient in the Jα18 gene (Jα18-/-) lack these cells but possess normal levels of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells (10). Type I NKT cells upon activation with αGalCer rapidly secrete large quantities of cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-4, which results in a cascade of events that includes activation of NK cells, dendritic cells, and B cells. Thus type I NKT-mediated cytokine secretion and modulation of NK cells and DC profoundly alters immunity against both self and foreign antigens, including microbes and viruses.

Sulfatide or 3’-sulfogalactosyl ceramide is enriched in several membranes including myelin in the CNS, pancreatic islet cells, and kidney epithelium (3). Sulfatide is a sulfolipid in which the 3’-OH moiety on the galactose is sulfated and the carbohydrate moiety is attached to the ceramide in a β-linkage. The ceramide moiety has two long hydrocarbon chains, one of sphingosine and the other of a fatty acid. Several species of sulfatide are present that vary in the acyl chain length (C16-C24), unsaturation, and hydroxylation. It has been proposed that during chronic inflammation or tissue damage self-glycolipids are presented by CD1d molecules. Indeed, in MS patients increased serum levels of glycolipids (14, 15) and antibodies directed against them have been reported (16, 17), and recently T cells specific for glycolipids have been isolated from MS patients. Notably their frequency in 5 active MS patients was 3 times higher compared to 5 normal individuals (12). Using cloned CD1d-restricted T cells in humans it has been demonstrated that the ganglioside GM1 binds well to CD1b, whereas sulfatide binds promiscuously to the a, b, c, and d CD1 molecules (12, 18). The upregulation of CD1 protein in macrophages and astrocytes in areas of demyelination in chronic-active MS lesions but not in silent lesions is consistent with the notion that they can present relevant antigens to NKT cells (19) and thereby become involved in the disease process. Infiltrating macrophages or DC can engulf sulfatide-enriched membrane fragments bound to anti-sulfatide antibodies using Fc receptors or by complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. When so activated these tissue-resident microglia, infiltrating macrophages, or DCs can present not only proteins but also glycolipids such as sulfatide locally in a CD1d-restricted manner to NKT cells. Therefore sulfatide is a potential autoantigen, and sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells might be modulated to influence the course of autoimmunity in the CNS. We have shown that although both subsets infiltrate into the CNS, only sulfatide-reactive type II but not type I NKT cells are enriched during EAE (10).

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is a CD4+ T cell-mediated autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation and demyelination in the CNS. EAE is a well-studied animal disease model for multiple sclerosis and is induced following immunization of susceptible animals with myelin proteins or their peptides in adjuvant. The immunizing peptides and the course of EAE from monophasic, relapsing & remitting, to chronic varies according to the mouse strain used. Additionally, adoptive transfer of myelin protein-reactive Th1/Th17-like CD4+ cells induces EAE, whereas Th2 myelin protein-reactive cells are generally protective (20-22). Th1 cells predominantly secrete IL-2 and IFN-γ. Th17 cells secrete IL-17 whereas Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.

Previously we have shown that a single prophylactic intraperitoneal injection of sulfatide in the absence of adjuvant can prevent the chronic EAE in C57BL/6J mice (10). Also, adjuvant-free administration of αGalCer or its analogs can prevent or enhance EAE depending upon the mouse strain (23-26). A recent study has shown the presence of anti-sulfatide antibodies in both SJL/J and BL/6 mice following the induction of EAE (27). SJL/J mice have a greater number of sulfatide-reactive NKT cells than BL/6 mice, making them a particularly favorable animal for investigation of EAE treatment (13). In this study we have used peptide/MHC class II tetramers specific for myelin epitope PLP139-151, which is restricted by the I-As MHC molecule to directly investigate the fate of pathogenic T cells in SJL/J mice following sulfatide administration. We found that sulfatide administration in the absence of adjuvant ameliorates relapsing-remitting as well as chronic EAE by targeting the encephalitogenic Th1/Th17 CD4+ T cells. Furthermore we found that a single synthetic long fatty acyl form of cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide is effective in the treatment of ongoing disease. Administration of sulfatide results in the inhibition of the effector function of the encephalitogenic PLP139-151-reactive CD4+ T cell population in the CNS and peripheral lymphoid organs. Interestingly, anergized type I NKT cells as well as dendritic cells play an important role in the sulfatide-mediated regulation of EAE, and the microglial population is also inactivated in sulfatide-treated animals. Since CD1 molecules are non-polymorphic, insight into the regulation mediated by type II NKT cells will be extremely valuable in the development of non-HLA-dependent therapeutic approaches to autoimmune demyelinating diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animals

SJL/J and C57BL/6J female mice (6-8 wk) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6-Jα18-/- mice originally generated in the laboratory of Taniguchi (28), were kindly provided by Mitch Kronenberg (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology). All mice were bred and maintained in specific pathogen free-conditions in the TPIMS animal facility. Treatment of animals was in compliance with federal and institutional guidelines and approved by the TPIMS Animal Care and Use Committee.

Glycolipid antigens and CD1d-tetramers

Purified bovine myelin-derived sulfatide (>90% pure) and semi-synthetic lysosulfatide and tetracosenoyl sulfatide was purchased from Matreya Inc., Pleasant Gap, PA. The cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide was chemically synthesized in collaboration with Prof. Chi-Huey Wong of The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla as described earlier (13). Synthetic αGalCer was provided by Y. Koezuka (Kirin Brewery Co., Tokyo, Japan). All lipids were dissolved in vehicle (0.5% polysorbate-20 (Tween-20) and 0.9% NaCl solution) and diluted in PBS. Murine CD1d was made in a baculovirus expression system as described earlier (10). PE-labeled mCD1d-tetramers loaded with αGalCer or PBS were generated as described earlier (10, 29).

MHC class II-tetramers

Recombinant MHC class II tetramers were produced essentially as described (30-32). Briefly, the cDNA for the I-As α-chain was elongated by overlapping PCR with sequences encoding for an acidic zipper sequence and a His6-tag and the I-As peptide/MHC class II tetramers specific for myelin epitope, PLP139-151, which is restricted by MHC molecule, I-As β-chain with the complementary basic zipper sequence and the BirA-dependent biotinylation substrate sequence (33). The cDNAs encoding for the peptides MBP84–96 (VVHFFKNIVTPRTP) and PLP139–151 (HCLGKWLGHPDKF) were attached to the 5’ end of the I-AS b-chain via a 6-aa linker. After cloning into baculovirus transfer vector pAcDB3 (BD Biosciences), recombinant baculoviruses were generated using the BaculoGold system (BD Biosciences) and grown suspension cultures of Sf9 cells in protein-free insect medium. Recombinant monomers were purified under native conditions from the supernatant and biotinylated, as described (33). Tetramers were formed by incubation with PE- or allophycocyanin-labeled streptavidin (Invitrogen or BD Biosciences).

Isolation and tracking of lymphocytes from the CNS

Spinal cords were extracted from different groups (4-7 animals in each) of mice after anesthesia and whole body perfusion with chilled PBS. Cell suspensions of infiltrating cells from the brain and spinal cords were separated by a discontinuous density gradient centrifugation, as described. Following a low speed (200 x g) centrifugation the cell suspensions were suspended in 70% Percoll (Pharmacia) in HBSS. This was overlaid by equal volumes of 37 and 30% Percoll and the gradient centrifuged at 500 x g for 15 min. Mononuclear cells were harvested from the 37-70% interface, washed in HBSS. In C57BL/6J mice we have routinely isolated 0.5 to 1 million cells from a single mouse at the peak of the disease. The number of infiltrating cells eventually decreased around 5-10 fold following recovery. The CNS-Infiltrating lymphocytes isolated as above were subjected to staining with αGalCer/CD1d-lipid tetramers or standard PCR analysis using Vα14- and Jα18-specific primers: Vα14F, GTCCTCAGTCCCTGGTTGTC; Jα18R, CAAAATGCAGCCTCCCTAAG.

Flow cytometry

Leukocytes were suspended in FACS buffer (PBS containing 0.02% NaN3 and 2% FCS), blocked (anti-mouse FcR-γ, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and stained with loaded mCD1d-tetramer-PE or PE-, FITC-, or PE-Cy5-labeled anti-mouse antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA or eBioscience, San Diego, CA) as indicated. Intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS) of liver mononuclear cells (MNCs) was carried out as described earlier (29). Analysis was performed on a FACS Calibur instrument using CellQuest software (version 4.0.2, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Induction and clinical evaluation of disease

For active EAE induction, mice were immunized s.c with 100-150 μg of PLP139-151 or MOG 35-55 emulsified in CFA; 0.15 μg pertussis toxin (List Biological, Campbell, CA) was injected i.p. in 200 μl saline on day 0 and day 2. Mice were observed daily for the clinical appearance of EAE. Disease severity was scored on a 5-point scale (23): 1, Flaccid tail; 2, hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis; 4, whole body paralysis; 5, death.

Measurement of antigen-specific proliferative and cytokine responses

Draining lymph nodes of mice were removed 10 days after s.c. immunization with the myelin antigens, and single cell suspensions were prepared. Lymph node cells (8 × 105 cells per well) were cultured in 96-well microtiter plates with peptides at concentrations ranging from 1.25 μg/ml to 40 μg/ml. IFN-γ, IL-4 or IL-17 cytokine secretion in the assay supernatants were determined using standard sandwich ELISA technique, as described earlier (29). All capturing and detecting antibody pairs were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Proliferation was assayed by the addition of 1 μCi 3H-thymidine (International Chemical and Nuclear, Irvine, CA) per well for the last 18 hours of a 5-day culture. Incorporation of 3H-thymidine was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Hepatic cell isolation and adoptive transfer

Hepatic lymphocytes were isolated using the Percoll gradient essentially as described earlier (29). Briefly following anesthesia with isoflurane (Baxter) mice were perfused with chilled PBS, and livers removed for the isolation of mononuclear cells (MNCs) using 35% Percoll gradient. CD11c+ DCs were purified from liver MNCs by positive selection with CD11c micro beads on a Mini MACS column (Miltenyi Biotec Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (>90% pure). CD11c+ DCs (1 × 106), purified from livers of donors one day after sulfatide or vehicle/PBS administration, were injected i.v. into recipients that were then immunized two days later for the induction of EAE.

Isolation of microglia and macrophages from CNS

Briefly, animals were sacrificed using CO2-inhalation and perfused with 40-50 ml chilled PBS. Single cell suspensions were rapidly prepared from brain and spinal cord in 10% FBS in HBSS by mincing and filtering through a 70 μM cell strainer (BD Falcon). After washing, cell suspensions were enzymatically digested for 60 minutes at 37° C with collagenase D (0.2 mg/ml, Roche) and DNase I (28 U/ml) in serum free HBSS. After washing, cells were resuspended in serum free HBSS, added to a 1.22 g/ml percoll solution (Sigma) and overlaid with a 1.088 g/ml percoll solution and then centrifuged at 2400 rpm for 20 minutes at RT. After removal of the fat and myelin layer at the top of the tube, cells were collected from the clear upper/interface phase. Cells were diluted in HBSS and washed, centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in FACS buffer for staining with indicated anitibodies and for cell sorting or flow cytometry analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for each group. Statistical differences between groups were evaluated by unpaired, one-tailed Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0a, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

Adjuvant-free administration of bovine brain-derived sulfatide or a synthetic immunodominant form, cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide, but not αGalCer reverses ongoing relapsing-remitting EAE in SJL/J mice

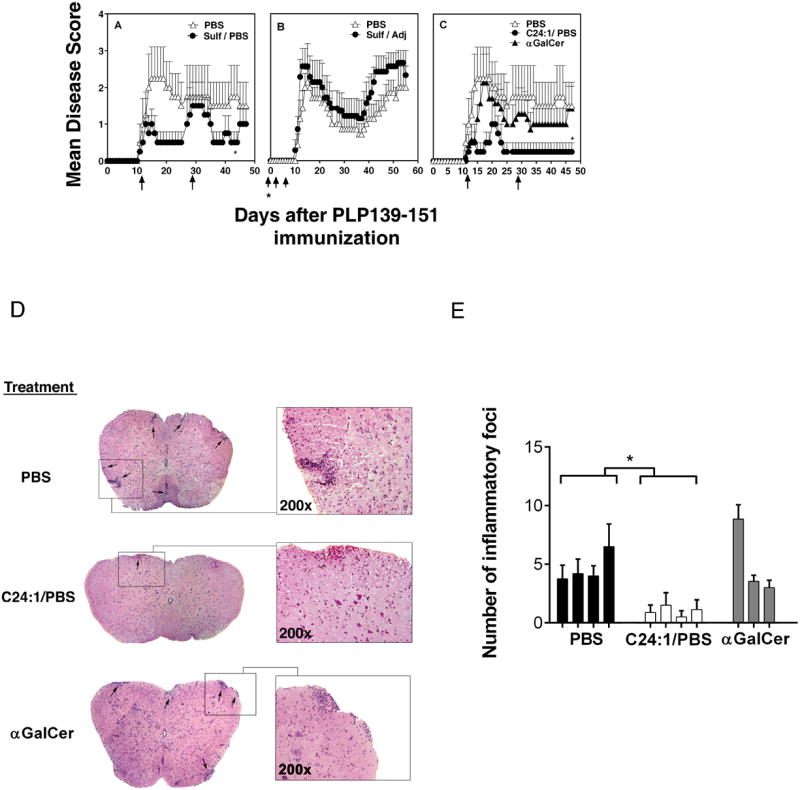

While a single prophylactic injection of myelin-derived sulfatide and not other self-glycolipids at the time of MOG immunization or even later can significantly protect C57BL/6J mice from induction of EAE in a CD1d-dependent manner (10), it has not been shown whether ongoing disease can be reversed following activation of type II NKT cells by sulfatide. Here we determined whether sulfatide administration can ameliorate the ongoing chronic and relapsing form of PLP139-151-induced disease in SJL/J mice. Groups of female SJL/J mice were administered i.p. with 20 μg sulfatide in vehicle/PBS or vehicle/PBS only, after antigenic challenge and following the onset of disease at around day ~11 and day ~30. As shown in Figure 1a, clinical signs of disease were significantly reduced and remained low in mice treated with sulfatide in comparison to those in the control or vehicle/PBS-treated group.

Figure 1. Treatment of ongoing relapsing-remitting EAE in SJL/J mice following adjuvant-free administration of brain-derived sulfatide or its immunodominant synthetic form cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide.

Groups (4-8 mice in each) of female SJL/J mice were injected i.p. with 20 μg of bovine brain-derived sulfatide in PBS/vehicle (A) or emulsified in the complete Freund’s adjuvant (B) or with synthetic cis-teracosenoyl sulfatide (C24:1) or αGalCer in PBS/vehicle (C) or with PBS/vehicle alone following the onset of PLP139-151/CFA/PT-induced EAE. Sulfatides or αGalCer in PBS were administered on day 11 and 29 following PLP immunization. Sulfatide emulsified in adjuvant was administered at the time of immunization followed by day 4 and day 7. Sulfatide or αGalCer treatment data are representative of 4 and 2 experiments respectively. *P values <0.05 (D) Inhibition of histological severity of EAE in SJL mice following treatment with synthetic cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide (C24:1) but not αGalCer. The spinal cords of SJL/J mice were analyzed 13 days after PLP/CFA/PT immunization. Histological sections following staining with H & E are shown. (E) Number of inflammatory foci in sections from groups (4 mice in each) of PBS/vehicle (PBS)- or C24:1 sulfatide/PBS- or αGalCer/PBS-treated mice are shown.

We found that sulfatide administered subcutaneously in adjuvant is unable to stimulate type II NKT cells and accordingly fails to cross-regulate type I NKT cells (Halder, et al., unpublished data). Similarly when a higher dose of sulfatide is administered emulsified with the PLP peptide in adjuvant the induced disease may be potentiated (27). Here we have determined whether the protective effect of an optimum dose (20 μg/animal) of sulfatide, as shown in Figure 1a, is lost when it is administered emulsified with the adjuvant. As shown in Figure 1b, sulfatide given with adjuvant does not reduce clinical symptoms of disease but rather appears to exacerbate EAE.

Bovine brain-derived sulfatide is a mixture of several different forms of sulfatide that vary in hydroxylation, fatty acid chain length, and in unsaturation. We have recently identified the most immunodominant form of sulfatide using proliferation, cytokine secretion, CD1d binding, and CD1d tetramer staining (13). Here we have determined whether this single immunodominant form of sulfatide alone can be used for the treatment of chronic-relapsing EAE in SJL/J mice. Groups of SJL/J mice with ongoing disease were injected i.p. with a synthetic cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide in vehicle/PBS or vehicle/PBS only. As shown in Figure 1c and Table 1, the immunodominant cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide administered following disease onset is more effective than the brain-derived mixture of sulfatides in ameliorating clinical signs of ongoing relapsing-remitting disease in SJL/J mice. Other forms of sulfatide with shorter or no fatty acid chain (lysosulfatide or C16:0) as well as tetracosenoyl sulfatide did not have any significant effect on the course of disease (Table 1). Interestingly inflammatory lesions as visualized by H&E staining of cross-sections of lumbar region of spinal cords also decreased significantly in sulfatide-treated animals (Fig. 1d and 1e). Also, sulfatide-treated mice have a reduced number of inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltrates in comparison to sections from the control PBS/vehicle group (Fig. 1e). These data suggest that the adjuvant-free administration with an immunodominant synthetic form of sulfatide is superior to bulk sulfatide for the treatment of ongoing chronic and relapsing form of EAE in SJL/J mice.

Table I.

Treatment of ongoing chronic and relapsing EAE in SJL/J mice with the immunodominant cistetracosenoyl sulfatide.

| Glycolipid | Incidence | Mean maximum score [no. of mice (maximum score)] | Mean day of onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10/13 | 2.38 [2(0), 2(1), 2(2), 4(3), 2(4), 1(5)] | 12.9 |

| Cis-tetracosenoyl | 8/17 | 1.06 [9(0), 4(1), 2(3), 2(4)] | 14.4 |

| Tetracosenoyl | 4/4 | 2.75 [1(2), 3(3)] | 12.3 |

| Lyso | 8/10 | 2.3 [1(1), 1(2), 4(3), 2(4)] | 12.0 |

Groups of female SJL/J mice were injected with 20 μg of cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide (C24:1), tetracosenoyl sulfatide (C24:0) or lysosulfatide (C16:0) following the onset of EAE (day 11, 29) and disease monitored.

Although prophylactic administration of αGalCer at the time of myelin protein immunization has been shown to prevent EAE, it has not been shown whether activation of type I NKT cells with αGalCer during ongoing chronic disease has a similar effect. Here we examined whether αGalCer injection can treat the ongoing chronic and relapsing form of EAE. Interestingly, treatment with αGalCer, at the time of disease onset has no significant effect on the course of EAE in SJL/J mice (Fig. 1c and Table 2). Similarly, inflammatory lesions and mononuclear cell infiltrates in spinal cords of αGalCer-treated mice did not differ significantly from the control PBS/vehicle group (Fig. 1d and 1e). It has been shown earlier (23) that αGalCer given prophylactically prior to disease onset can prevent EAE in BL/6 mice. However it is notable that while C57BL/6 mice are protected by prophylactic injection with αGalCer (2 μg/animal) prior to onset, a similar dose of αGalCer at the time of disease onset repeatedly caused rapid death of most of the mice in less then 24 hours (see Table 2). Even a lower dose of αGalCer injection during ongoing EAE did not have a significant influence on the course of EAE. These data suggest that targeting activation of type II NKT cells with cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide is a reliable method for the treatment of ongoing chronic and relapsing EAE.

Table II.

Survival rate of mice treated during ongoing EAE with different glycolipids.

| MICE | TREATMENT OF ONGOING DISEASE (# of animal death/total # of animals) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αGalCer | Sulfatide | Cis-tetracosenoyl | Mono-GM1 | |

| C57/BL6 | 8/9 | 0/16 | 0/4 | 0/5 |

|

| ||||

| SJL/J | 0/9+ | 0/22 | 0/42 | 0/5 |

No death, but no significant amelioration of disease

Survival rate of mice treated with indicated glycolipids: αGalCer, bovine brain-derived sulfatide, synthetic cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide (C24:1) and mono-GM1. Groups of mice were injected i.p. with 4 μg of αGalCer, or 20 μg each of sulfatide, cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide or mono-GM1 following the onset of EAE (day 11).

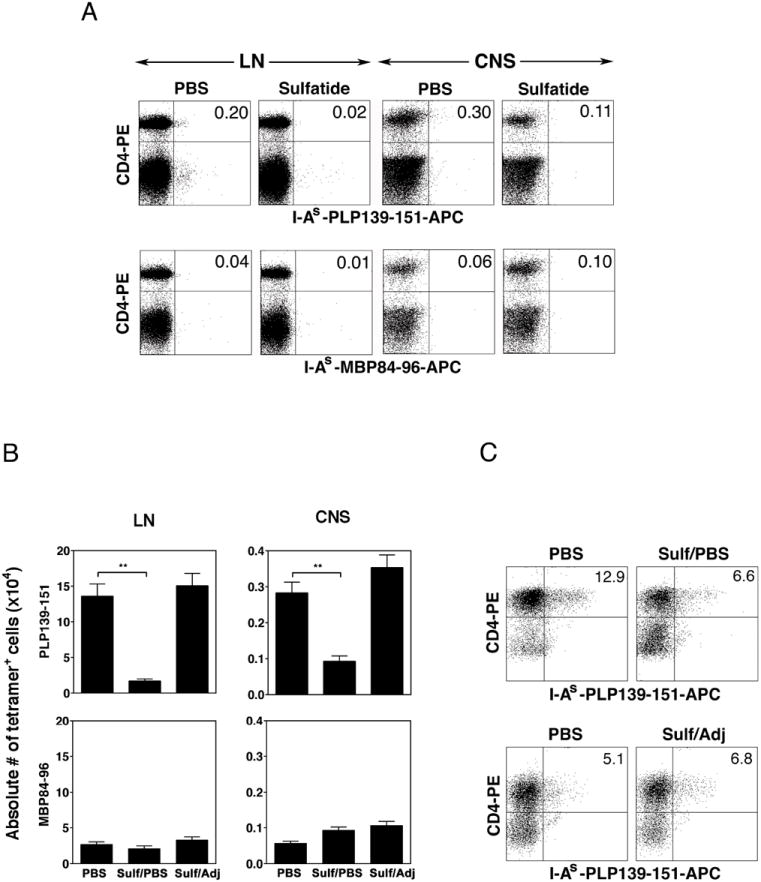

Reduced numbers of pathogenic PLP-reactive-CD4+ T cells in draining lymph nodes as well as in CNS-infiltrating cells in mice treated with adjuvant-free sulfatide

During the course of PLP139-151-induced relapse-remitting EAE in SJL/J mice there is an elevated level of PLP-reactive CD4+ T cells in the periphery as well as in the target organ, the CNS. First we determined whether the decrease in clinical symptoms of disease in sulfatide-treated mice results in a decrease in the number of encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells both in the draining lymph nodes and CNS. We have used PLP139-151/IAs-tetramers for the identification of encephalitogenic T cells. In parallel, MBP84-96/IAs-tetramers were used as a negative control. As shown in Figure 2a, there is a tenfold reduction in the percentage of disease-causing PLP139-151/-IAs_tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in draining lymph nodes in sulfatide treated mice in comparison to that in vehicle/PBS-treated animals. There was no significant difference in the number of MBP84-96/IAs-tetramer+ cells.

Figure 2. Decrease in numbers of pathogenic PLP reactive CD4+ T cells in the draining lymph nodes and in the CNS following treatment with sulfatide.

(A) A representative flow cytometric profile of lymph node cells and CNS-infiltrating cells isolated ex vivo from SJL/J mice and stained with PLP139-151- I-As-tetramers or an irrelevant MBP84-96- I-As-tetramers and anti-CD4 mAb. The flow cytometric profile shown is derived from the gate that includes all of the mononuclear cells and excludes the dead cells and red blood cells. Groups of animals were treated with sulfatide in PBS/vehicle or sulfatide emulsified in CFA or with PBS/vehicle only, as in Figure 1. Single cells suspensions of draining lymph node cells or the CNS-infiltrating lymphocytes were stained with tetramers or other indicated antibodies and analyzed by flowcytometry. Lymph node cells and CNS-infiltrates were isolated 6 and 19 days, respectively following immunization with PLP139-151/CFA. (B) A summary of data from sulfatide-treated and control mice is shown. *P values <0.01. These data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

(c) Flow cytometric profile of in vitro cultured lymph node cells stained with PLP139-151/I-As tetramers and anti-CD4 mAb. Groups of PLP139-151/CFA-immunized SJL/J mice were treated with PBS/vehicle (PBS), sulfatide/PBS (sulf/PBS) or sulfatide in adjuvant (sulf/adj). Lymph node cells were isolated 10 days following immunization and cultured with PLP139-151 peptide in vitro for 4-6 days and stained with indicated antibodies. Representative flow cytometry profiles are shown from each group.

Since sulfatide is enriched in the CNS and can be presented in the context of CD1d to infiltrating type II NKT cells, we wanted to examine whether encephalitogenic conventional CD4+ T cells are also decreased in the CNS. Groups of SJL/J mice were immunized subcutaneously with PLP139-159/CFA/PT for the induction of disease and injected i.p. with sulfatide in vehicle/PBS or vehicle/PBS only. At the peak of disease during day 15-19, CNS-infiltrating mononuclear cells were isolated and subjected to flow cytometry following staining with tetramers and the indicated antibodies. In sulfatide-treated mice encephalitogenic PLP139-151/IAs-tetramer+ CD4+ T cells were about a third in number (0.11% to 0.30%) in comparison to those in the vehicle/PBS-treated mice (Fig. 2a). These data demonstrate that sulfatide treatment reduces the number of encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells in CNS (Fig. 2a). Accordingly, as summarized in Figure 2b, the absolute number of the pathogenic PLP139-151-reactive CD4+ T cells is significantly reduced both in the draining lymph nodes and in the CNS tissues from sulfatide-treated animals.

In parallel, a comparison of the number of PLP139-151/IAs-tetramer+ cells both in the lymph nodes and in CNS between adjuvant-free vs. adjuvant-emulsified sulfatide-treated mice revealed that the encephalitogenic T cells are diminished in animals treated with adjuvant-free sulfatide but not in mice injected with sulfatide emulsified in adjuvant (see Fig. 2b). To further confirm tetramer staining and a decrease in PLP139-151-reactive encephlitogenic T cells in sulfatide-treated mice, draining lymph node cells were cultured in vitro with the immunizing peptide and stained with PLP139-151/I-As-tetramers. Figure 2c clearly shows a substantial decrease in the percentage of tetramer+ cells only in adjuvant free sulfatide (sulf/PBS) but not in adjuvant emulsified sulfatide-treated (sulf/Adj) mice in comparison to mice in control (PBS) group.

Treatment of SJL mice with adjuvant-free sulfatide also leads to a significant decrease in PLP139-151-reactive Th1/Th17 cells

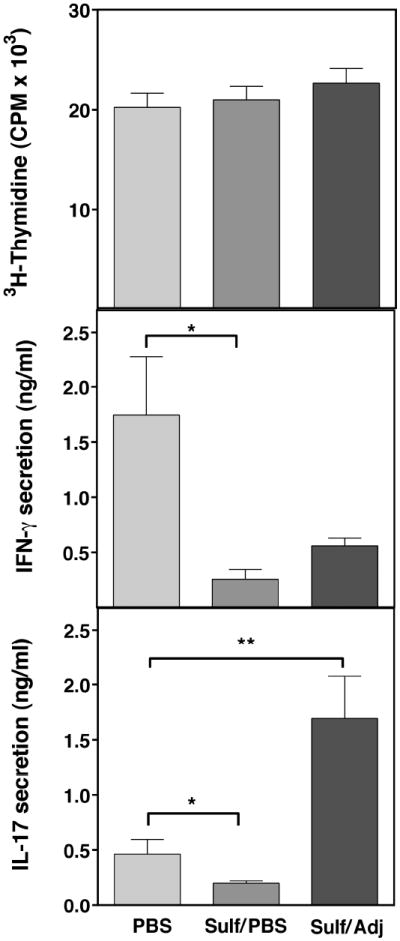

We next determined the proliferation and secretion of cytokines IFN-γ (Th1) or IL-17 (Th17) by PLP-reactive CD4+ T cells following treatment of mice with sulfatide. Since the frequency of tetramer+ cells was very low, levels of both cytokines were determined directly ex vivo in PLP139-151-reactive T cells isolated from draining lymph nodes of mice treated with adjuvant-free or adjuvant-emulsified sulfatide, or PBS. As shown in Figure 3 though the proliferative response to PLP139-151 was similar in different groups there was a significant decrease in both IFN-γ and IL-17 secretion by PLP-reactive T cells isolated from adjuvant-free sulfatide-treated animals in comparison to the untreated group. Notably, while there was some reduction in IFN-γ secretion in adjuvant-emulsified sulfatide-treated mice, IL-17 secretion by PLP-reactive T cells was significantly enhanced. These data indicate a significant inhibition of both the Th1 and Th17 responses only following adjuvant-free administration of sulfatide in SJL/J mice. These data also explain why sulfatide administered with adjuvant is able to potentiate disease owing to an increase in IL-17-secreting encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. Inhibition of pathogenic-PLP reactive, IFN-γ (Th1) or IL-17 (Th17) secreting CD4+ T cells is dependent upon the administration of sulfatide in PBS and not when sulfatide is administered emulsified with adjuvant.

Groups of SJL/J mice were treated with sulfatide (20 μg/mouse) in PBS/vehicle or emulsified in CFA or with PBS/vehicle only. Subsequently all treated mice were subcutaneously immunized with PLP139-151/CFA. Six days later draining lymph node cells were prepared and used in in vitro proliferative recall assays with a graded concentration of PLP139-151 peptide. Supernatants from these cultures were examined for the secretion of IFN-γ and IL-17 using typical sandwich ELISA assays. *P values <0.05, **P values <0.01

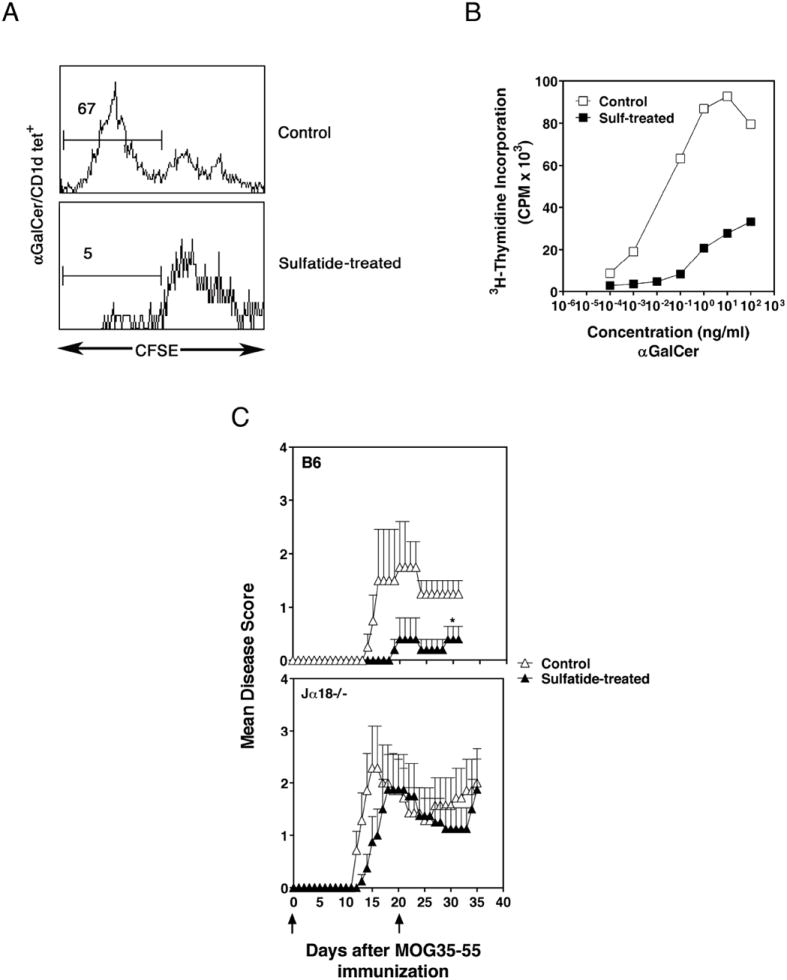

Induction of anergy in type I NKT cells following sulfatide administration in SJL/J mice

Recently we have identified a novel immunoregulatory pathway in which activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells leads to anergy induction in type I NKT cells mediated by dendritc cells and a significant protection from liver injury following Con A injection or following ischemic reperfusion-induced in C57BL/6J mice (29, 34). Here we determined whether type I NKT cells are also anergized following sulfatide administration in SJL/J mice. Groups of SJL/J mice were administered with adjuvant-free sulfatide, and anergy induction in type I NKT cells was examined by proliferation of αGalCer/CD1d-tetramer+ cells by CFSE dilution (Fig. 4a) as well as by 3H-thymidine incorporation (Fig. 4b) in response to an in vitro challenge with αGalCer. As shown in Figure 4a and 4b, while type I NKT cells (αGalCer/CD1d-tetramer+) proliferate in response to the cognate ligand αGalCer in the PBS-treated group, their proliferative response is significantly inhibited in sulfatide-treated animals. This inhibition of proliferation of type I NKT cells can be reversed by the addition of IL-2 (data not shown). These data suggest that type I NKT cells are anergized following activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells in SJL/J mice.

Figure 4. Induction of anergy in type I NKT cells following adjuvant-free sulfatide administration in SJL/J mice.

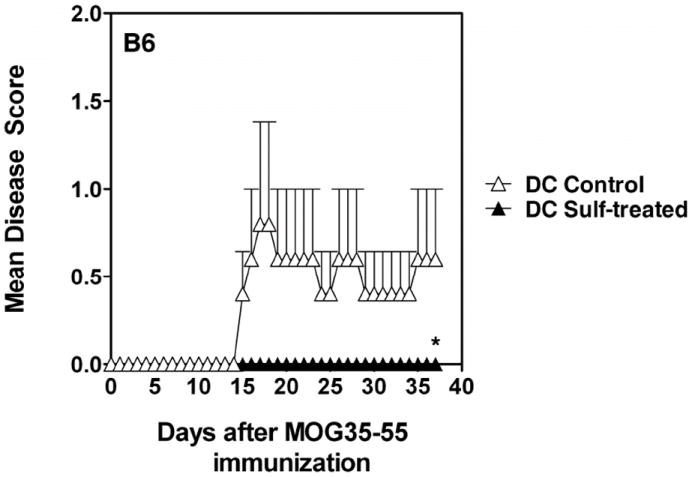

(A) CFSE dilution profiles of αGalCer/CD1d-tetramer+ cells in splenocytes from sulfatide- or PBS/vehicle-treated mice are shown. Splenocytes isolated 6 hr following sulfatide/PBS/vehicle injection were labeled with CFSE and stimulated in vitro with αGalCer, as described earlier (29). (B) In parallel incorporation of 3H-thymidine in triplicate cultures of splenocytes from sulfatide or PBS/vehicle-injected mice were measured in response to the in vitro challenge with αGalCer. Data are representative of 2 individual experiments. (C) Loss of sulfatide-mediated protection from EAE in mice deficient in type I NKT cells. Groups of C57BL/6 (B6) or type I NKT-deficient Jα18-/- (Jα18-/-) mice (4-5 mice in each group) were injected with sulfatide in PBS/vehicle or PBS/vehicle alone at day 1 and 20 in relation to MOG35-55/CFA/PT for the induction of EAE. Disease symptoms were monitored daily until day 32-35. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P values <0.05

Sulfatide-mediated inhibition of EAE is lost in mice lacking type I NKT cells

Anergic type I NKT cells have been recently shown to limit inflammation-induced damage in the liver disease mediated by NKT cells (29, 34). Here we examined the role of anergic type I NKT cells in the regulation of autoimmune disease mediated by myelin protein-reactive MHC class II-restricted CD4+ T cells. Since SJL/J mice deficient in type I NKT cells are not available, we have used Jα18-/- in the C57BL/6 background to examine whether anergic type I NKT cells are required for sulfatide-mediated protection from EAE. Groups of WT (C57BL/6J) and type I NKT-deficient (Jα18-/-) mice were immunized for induction of EAE and were treated either with sulfatide/PBS or PBS only, and clinical signs of disease were monitored daily. As shown in Figure 4c, sulfatide treatment did not significantly protect Jα18-/- mice from EAE, though the disease was delayed in comparison to the control group. As expected, EAE was significantly suppressed in the WT mice. These data suggest that anergic type I NKT cells behave like regulatory cells and play an important role in regulation of autoimmunity.

Adoptive transfer of CD11c+ dendritic cells from sulfatide-treated animals prevents disease in naïve recipients

We have earlier shown that activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells leads not only to inactivation of type I NKT cells but also to tolerization of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) (29, 34). We investigated whether tolerized DCs also participate in inhibiting expansion of the encephalitogenic myelin-protein-reactive CD4+ T cells. Liver CD11c+ DCs were isolated from groups of mice that were administered sulfatide (20 μg/mouse) or PBS/vehicle. One day later, positively selected CD11c+ cells (1 × 106) were isolated and adoptively transferred into naïve recipients that were subsequently immunized for the induction of EAE. Notably, mice in the group that received CD11c+ DCs from sulfatide-treated animals were significantly protected from induction of EAE in comparison to animals that received DCs from PBS/vehicle injected mice (Fig. 5). These data suggest that tolerized DCs following sulfatide administration play an important role in this immune regulatory pathway.

Figure 5. Adoptive transfer of hepatic DCs from sulfatide-treated but not from control mice prevents EAE in recipient animals.

Groups of BL/6 mice were injected with sulfatide (20 μg, i.p.) or PBS/vehicle. One-day later, purified liver CD11c+ DCs (1 × 106 cells/mouse) from both groups of donor mice were injected i.v. into recipients. Two days later, recipients were injected with MOG35-55/CFA/PT for the induction of EAE. Disease severity was monitored every day and until day 35. These data are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P values <0.05

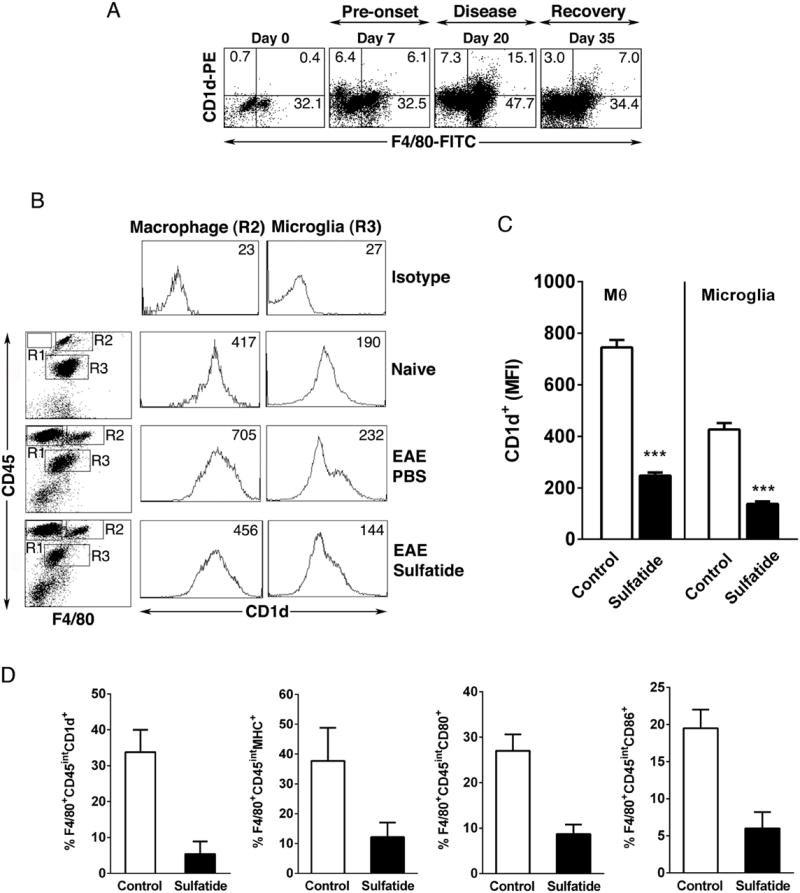

Inhibition of costimulatory molecules and CD1d expression on the CNS-resident microglia/macrophages following sulfatide administration

Since sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells are enriched in the CNS during EAE and in situ activation of microglia is required for CNS demyelination, we examined whether activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells also influences activation of microglia. Several studies have shown upregulation of costimulatory molecules on microglia following their activation during EAE. Here we examined whether expression of CD1d, MHC and other costimulatory molecules on microglia is modulated during disease and whether treatment with sulfatide influences their expression. Using a percoll gradient, microglia-enriched mononuclear cells were isolated from diseased SJL/J mice at day 0, day 7 (pre-onset), day 20 (peak disease) and day 35 (remission), and F4/80+ cells were analyzed for their expression of CD1d using dual color flowcytometry. While both microglia and macrophage populations express a low level of CD1d at day 0, by day 7 through day 20 expression increases significantly and then decreases during remission (Fig. 6a). Next we used 4-color flowcytometry to carefully analyze CD1d expression on the infiltrating macrophages and resident microglial populations individually in naïve mice, untreated mice with EAE, and sulfatide-treated mice on day 20. Data presented in Figure 6b, 6c and 6d show a significant increase in CD1d-, MHC class II-, CD80-, CD86-expressing CD45+intermediate/F4/80+ microglial cells as well as CD45+high/F4/80+ macrophage/DC populations during EAE. Notably in mice treated with sulfatide a significantly reduced level of costimulatory molecules, MHC and CD1d expression was found on both macrophages as well as microglial populations (Fig. 6). These levels were similar to those in mice before disease onset.

Figure 6. Modulation of CD1d expression on macrophages and microglial populations during EAE and following treatment with sulfatide.

(A) Up-regulation of CD1d expression in CNS during ongoing chronic-relapsing EAE in SJL/J mice. Total CNS cells were isolated from brain and spinal cord in the indicated time points from SJL/J mice (2-3 mice in each time points) immunized with PLP139-151/CFA for the induction of EAE. Two-color staining was performed using mAbs, e.g., CD1d-PE and F4/80-FITC and analyzed by flowcytometry. The percent positive cells are indicated in each quadrant. One of two representative experiments is shown.

(B) Inhibition of CD1d expression on CNS-resident microglia and macrophage populations following sulfatide administration. (Top panels) Mononuclear cells specifically enriched in microglia (CD45int/F4/80+, gate R3) and macrophages (CD45hi/F4/80+, gate R2) were isolated on day 19 from the CNS of diseased SJL/J mice (n = 3) using percoll gradients. Cells were pooled from naïve unimmunized as well as PBS or sulfatide-treated PLP139-151/CFA-immunized mice and stained with the indicated CD45-PE, F4/80-FITC antibody and CD1d-APC and analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers indicate mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). All of the flow cytometric profiles shown are derived from the gate that includes all of the mononuclear cells and excludes the dead cells and red blood cells. Sulfatide (20 μg) was injected on d14 and d17. EAE scores were lower in sulfatide-treated mice (2,1) in comparison to the control PBS/Vehicle-injected mice (4,3). One of 2 independent experiments is shown.

(C) A summary from the data related to the CD1d expression (MFI) in macrophages and microglia from groups of mice in Fig. 1B treated with sulfatide/PBS (sulfatide) or with PBS as control are shown. *** P value <0.001 (D) Reduced expression of CD1d, MHC class II, CD80 and CD86 molecules on microglial populations following treatment with sulfatide. Mononuclear cells were isolated from the spinal chords of mice treated with sulfatide or PBS (control) day 19 following induction of EAE. The cells were gated on F4/80 and CD45intermediate expression and percentage of F4/80+CD45int cells expressing CD1d, MHC class II, CD80 and CD86 are shown in bar graph. Results are representative of 2 experiments with 4-5 mice per group. P value <0.05

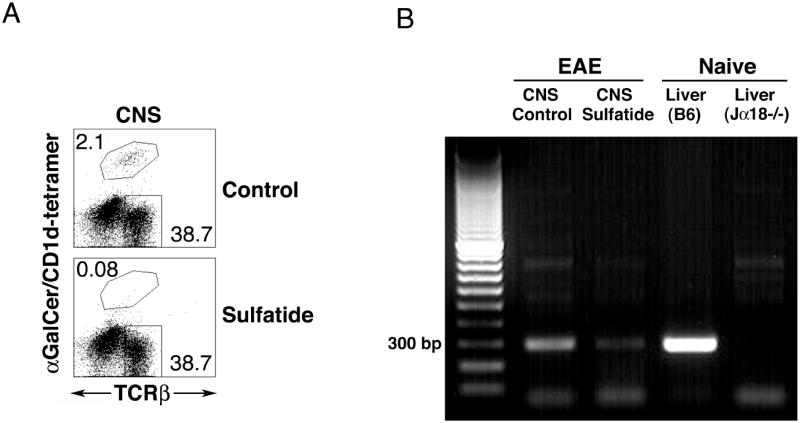

Loss of the CNS-infiltrating type I NKT cells during EAE in mice treated with sulfatide

Next we examined the number of infiltrating type I NKT cells into CNS during EAE (Fig. 7). Since sulfatide administration leads to anergy induction in type I NKT cells in the periphery, we wanted to determine whether their numbers are reduced in the CNS at the peak of the demyelination. As shown in Figure 7a, αGalCer/CD1d-tetramer+ cells are significantly reduced in CNS-infiltrating cells in mice treated with sulfatide in comparison to those in the control group (0.08% vs. 2.1%). Using PCR, we further investigated whether the reduced staining of type I NKT cells with αGalCer/CD1d-tetramers was due to their reduced number in the CNS or due to down-regulation of their TCR. As shown in Figure 7b, a comparison of the PCR product amplified using TCR-specific primers for type I NKT cells in the CNS infiltrate from the sulfatide-treated mice showed a substantial reduction (~3.5 fold) in relation to PBS/vehicle-injected animals. Collectively these data indicate a significantly reduced number of type I NKT cells infiltrating into CNS during EAE in sulfatide-treated animals.

Figure 7. Elimination of type I NKT cells in the CNS following sulfatide administration.

(A) CNS-infiltrating cells were isolated from brain and spinal cord during chronic disease (day 19) in PLP139-151/CFA-immunized SJL/J mice (3-4 mice/groups) treated with PBS/vehicle (control) or sulfatide/PBS (Sulfatide) and two-color staining was performed using αGalCer/CD1d-tetramers and anti-TCRβ and analyzed by flowcytometry. The flow cytometric profile shown is derived from the gate that includes all of the mononuclear cells and excludes the dead cells and red blood cells. The numbers indicate % positive cells. Sulfatide was injected on day 14 and 17 in EAE mice. These data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) CNS-infiltrating cells as above in Figure 7a were isolated and 1.5 million cells from PBS/Vehicle- (control) or sulfatide/PBS-treated (sulfatide) mice and subjected to PCR analysis using Vα14- and Jα18-specific primers for the estimation of type I NKT cells. DNA samples from livers of BL/6 and Jα18-/- mice were included as positive and negative controls.

Discussion

The data presented here demonstrate that the administration of bulk purified sulfatide or a synthetic immunodominant species, cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide, in the absence of adjuvant but not in an adjuvant-emulsified form, leads to reversal of ongoing chronic-relapsing EAE in SJL/J mice. Furthermore our data begin to identify the cellular mechanism(s) by which activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells control autoimmunity. As shown using PLP139-151/I-As-tetramers, pathogenic class II MHC-restricted Th1 and Th17 responses are significantly inhibited following treatment with sulfatide. Consistent with our earlier studies of NKT-mediated liver diseases in BL/6 mice (29, 34), anergic type I NKT cells as well as tolerized dendritic cells are involved in this sulfatide-mediated regulation of EAE in SJL/J mice. Furthermore sulfatide administration also leads to a significant inhibition in the expression of several activation markers on the CNS-resident microglial population, including CD1d molecules that are involved in autoimmune demyelination. Collectively our data suggest that the regulation of EAE following activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells modulates key cellular players in peripheral as well as lymphoid compartments, including inhibition of the effector MHC class II-restricted myelin-protein reactive T cells, type I NKT cells, DCs and microglial activation in the CNS.

Sulfatide-reactive CD1d-restricted T cells represent a major subset of type II NKT cells in both H-2b and H-2s haplotypes as examined by staining with sulfatide/CD1d-tetramers in C57BL/6J and in SJL/J mice respectively (13). Also cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide (C24:1) is an immunodominant form in both mouse haplotypes (13). Interestingly cis-tetracosenoyl sulfatide/CD1d-tetramer+ cells are around 2 fold higher (1.3% vs. 2.5%) in SJL/J mice in comparison to those in C57BL/6 mice (13). In contrast αGalCer/CD1d-tetramer+ cells in spleen of SJL/J mice are about half (0.74% vs. 1.6%) of those in BL/6 mice (Kumar unpublished data) consistent with the earlier report in the thymus (35). This may explain the effectiveness of C24:1 sulfatide in stimulating type II NKT cells and control of EAE in SJL/J mice despite the presence of lower number of type I NKT cells. A lower number of type I NKT cells in SJL/J mice may also explain the reduced cytotoxicity and incidence of death in SJL/J mice in comparison to BL/6 animals following αGalCer administration during ongoing EAE (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

It is clear from our data that activation of type II NKT cells using brain-derived sulfatide or a synthetic immunodominant species reverses ongoing chronic and relapsing course of disease in SJL/J mice. However this occurs only if the sulfatide is administered in PBS/vehicle and not when it is emulsified in CFA/IFA. These data are consistent with an earlier report showing that sulfatide emulsified in adjuvant did not protect mice from EAE but appeared to exacerbate the clinical symptoms owing to an anti-sulfatide antibody response (27). It is not yet known whether the anti-sulfatide antibody response or the potentiation of EAE utilizes a CD1d-dependent pathway. It is important to note that the activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells as well as the subsequent anergy induced in the type I NKT population occurs only when sulfatide is administered i.p. and not i.v. or subcutaneously in the absence of adjuvant. This is distinct from the case of αGalCer, which can be administered i.v., i.p. or intranasally for the activation of type I NKT cells. Studies are ongoing to understand the necessity of an i.p. injection of sulfatide for the activation of these type II NKT cells.

We have noted that while treatment of chronic EAE in BL/6 mice with sulfatide completely ameliorates disease in some mice, it has only a partial effect in others. This effect may result from a difference in number or activation state of type I NK T cells in different animals. In several experiments we have found that sulfatide administration provides the best protection in those C57BL/6 animals that have a lower (around ~20% in the liver) and not a higher (>35%) number of type I NK T cells, as delineated with αGalCer/CD1d-tetramers in naïve conditions. We are investigating whether the higher number of type I NKT cells in some animals represents a differential activation/expansion that might be present in seemingly identically housed animals of the same strain.

Consistent with our data here in the EAE model, long fatty acyl analogs of sulfatide, including tetracosenoyl sulfatide activate a subset of type II NKT cells in NOD mice and significantly inhibit the development of type 1 diabetes in a CD1d-dependent fashion (36). Despite the prevalence of C16:0 sulfatide in the pancreatic tissue, administration of the C16:0 isoform does not suppress diabetes. In contrast, C24:0 and C24:1 sulfatides are predominant in myelin. These data suggest that the long fatty acyl form of sulfatide or similar analogs may be better suited for intervention in autoimmune diseases. Recently we have determined the crystal structure of the lyso-sulfatide/CD1d/TCR trimolecular complex and found that different sulfatide isoforms may bind in a similar fashion to CD1d as well as to the TCR (9). Additionally we have shown that there is an overlap in the TCR repertoire of type II NKT cells reactive to different isoforms of sulfatide (37). Therefore it is likely that the differential ability of different sulfatide isoforms to activate responsive type II NKT cells may relate to the stability of the various antigen-receptor complexes in vivo, strength of antigen presentation, or their ability to efficiently activate CD1d-restricted T cells in the naïve repertoire.

An important aspect of our results combined with others is that the manner and timing of the activation of both type I and type II NKT cells affects the results observed. While activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells as described ameliorates ongoing EAE, αGalCer-mediated activation of type I NKT cells fails to reverse clinical symptoms of ongoing chronic or chronic and relapsing disease (Fig. 1 and Table 2). In fact injection of αGalCer during ongoing EAE appears to exacerbate clinical symptoms of disease in both H-2s and H-2b mouse haplotypes. Particularly in BL/6 mice, administration of αGalCer during ongoing disease leads to rapid death within 24 hrs, perhaps owing to a cytokine storm (Table 2). This is in contrast to earlier studies demonstrating prevention of disease when αGalCer is administered prophylactically before or simultaneously with immunization with myelin protein antigens (23, 25, 38). Several studies have shown that activation of type I NKT cells with αGalCer under different conditions can skew their response in a Th1- or Th2-like direction. Since there is a pre-existing inflammatory milieu following MOG/CFA/PT immunization, αGalCer administration further exacerbates these responses and fails to provide protection from disease. Consistent with the Th1 skewing of the response, αGalCer exacerbation of disease is blunted in IFN-γ-deficient mice (23). Collectively, our data suggest that strategies targeting activation of type I NKT cells with αGalCer or its analogs must be carefully designed in the treatment of an ongoing inflammatory response during autoimmune disease.

We have shown that the numbers as well as cytokine secretion (IFN-γ and IL-17) of encephalitogenic PLP-reactive CD4+ T cells are significantly decreased in both draining nodes as well in the CNS-infiltrating cells following treatment with sulfatide. Consistent with our data it has been suggested that type I NKT cells can inhibit the development of Th17 cells in steady state as well (39). Data presented here also suggest that anergic type I NKT cells assist in the control of EAE, as mice deficient in type I NKT cells are not protected from MOG-induced EAE following treatment with sulfatide (Fig. 4c). These data are consistent with studies showing that type I NKT-mediated inflammatory diseases of liver, kidney and lung are also inhibited following sulfatide-mediated activation of type II NKT cells in a CD1d-dependent pathway (29, 34, 40, 41).

Our data show (10, 42) that although both NKT subsets infiltrate into the CNS during the course of EAE, the sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells but not the αGalCer-reactive type I NKT cells are enriched. Since CD1d expression is also enhanced in the CNS during disease, it is likely that type II NKT cells are activated locally by presentation of myelin-derived sulfatide, resulting in the inhibition of microglial activation and consequently blocking the expansion or reactivation of encephalitogenic PLP-reactive CD4+ T cells required for demyelination. It is also interesting that type I NKT cells infiltrating into CNS during EAE are lost following sulfatide administration (Fig. 7a and 7b).

Our results demonstrate the importance of DCs in the sulfatide-mediated immune regulation pathway. Since anergy induction in type I NKT cells following sulfatide administration is dependent upon dendritic cells (3, 5, 29, 34, 37, 43) it is likely that tolerized DCs play a major role in dampening the expansion or activation of PLP139-151-reactive I-As-restricted CD4+ T cells. Consistent with this finding it has been shown earlier that conventional DCs play a crucial regulatory role in suppressing immunosurveillance against several tumors as well as autoimmunity mediated by NKT cells (43, 44). Anergy induction in type I NKT cells following repeated injections with αGalCer also leads to induction of non-inflammatory DCs that inhibit autoimmune diseases (45, 46). Indeed the transformation of type I NKT cells from promoters to suppressors of the inflammatory response requiring DCs or monocytes has recently been shown in autoimmune diabetes and EAE (45, 47, 48). Consistent with the role of tolerized DCs, our data clearly show that adoptive transfer of DCs alone from sulfatide-treated animals is able to protect recipients from EAE. We are investigating potential pathways including ERK1/2 signaling (49) or IL-10 secretion (50) or ICOS/PD-1 dependent signaling (51, 52) by which DCs are tolerized following NKT cell subset interactions leading to control of inflammatory response.

Active tissue injury in CNS demyelination in MS and EAE is associated with the inflammatory infiltrate containing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as activated microglia/macrophages (53). During EAE, inflammation starts with the infiltration of Th1/TH17 cells and is followed by microglial activation and recruitment of macrophages and CD8+ T cells into the CNS. Activated microglia are a potent source of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and actively participate in propagation of autoimmunity in the CNS (54, 55). These cells play a major role in the recruitment of lymphocytes as well as in presenting myelin-derived antigens locally. Since NKT cells also infiltrate CNS ((10) and Fig. 7), it is not surprising that their interaction locally influences the activation of microglial cells. Our data indicate that sulfatide treatment tolerizes not only dendritic cells in the periphery but also the microglial population in the CNS (Fig. 6). In vitro treatment with higher concentrations of sulfatide can also result in the activation of microglial cells and astrocytes in a CD1d-independent manner (56). It is important to emphasize that most of the vivo studies performed by us as well as others, administration of 20 μg of sulfatide results in activation of type II NKT cells and modulation of inflammatory condition in a CD1d-dependent manner (6, 10, 34, 40, 41, 57). Owing to paucity of sulfatide-reactive T cells attempts are being made to generate a cis-tetracosenyl sulfatide-reactive TCR transgenic lines for further careful analysis of type II NKT cells. Our preliminary data also suggest that CD1d expression on microglial cells from mice with EAE is functional, as they are able to stimulate NKT cells in antigen-presentation assays in vitro (Data not shown). It will be interesting to investigate whether pathways by which these two antigen-presenting populations are inactivated are similar or involve different signaling molecules. We have begun to undertake a critical study using a micro-RNA screening strategy to investigate the mechanism of tolerance induction in mDC and in the microglial population.

Collectively, data presented here further shed light on a novel immunoregulatory mechanism by which activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT cells suppresses inflammatory class II MHC-restricted pathogenic CD4+ T cell responses in a T cell–mediated autoimmune disease. In this regulatory pathway, mDCs play an important role leading to inactivation of type I NKT cells as well as inhibition of the activation and/or effector cytokine secretion by conventional MHC class II –restricted encephalitogenic T cells. Furthermore inactivation of microglia in the CNS contributes to an efficient limitation of the inflammatory response and protection from EAE. Recently a delicate balance between activation of sulfatide-reactive type II NKT, type I NKT, as well as FoxP3+ CD4+ Treg has also been shown to be critical for the suppression of tumor immunity (58). Therefore understanding the molecular events leading to activation or inactivation of type I vs. type II NKT cell subsets by self-lipids is important for autoimmunity as well as anti-tumor immunity.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all members of Kumar’s laboratory for their help and Drs. Randle Ware and Monica Carson, University of California Riverside for a critical reading of the manuscript and for help with the microglia isolation protocol respectively.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 CA100660 and the Multiple Sclerosis National Research Institute to VK.

Abbreviations used

- αGalCer

α–galactosylceramide

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- NKT

natural killer T cells

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- PLP

myelin proteolipid protein

References

- 1.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrenberg P, Halder R, Kumar V. Cross-regulation between distinct natural killer T cell subsets influences immune response to self and foreign antigens. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:246–250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronenberg M, Rudensky A. Regulation of immunity by self-reactive T cells. Nature. 2005;435:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nature03725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar V. NKT-cell subsets: Promoters and protectors in inflammatory liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;59:618–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhost S, Sedimbi S, Kadri N, Cardell SL. Immunomodulatory type II natural killer T lymphocytes in health and disease. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76:246–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. NKT cells in immunoregulation of tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ni.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girardi E, Maricic I, Wang J, Mac TT, Iyer P, Kumar V, Zajonc DM. Type II natural killer T cells use features of both innate-like and conventional T cells to recognize sulfatide self antigens. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:851–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahng A, Maricic I, Aguilera C, Cardell S, Halder RC, Kumar V. Prevention of autoimmunity by targeting a distinct, noninvariant CD1d-reactive T cell population reactive to sulfatide. J Exp Med. 2004;199:947–957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhost S, Lofbom L, Rynmark BM, Pei B, Mansson JE, Teneberg S, Blomqvist M, Cardell SL. Identification of novel glycolipid ligands activating a sulfatide-reactive, CD1d-restricted, type II natural killer T lymphocyte. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:2851–2860. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shamshiev A, Donda A, Carena I, Mori L, Kappos L, De Libero G. Self glycolipids as T-cell autoantigens. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1667–1675. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199905)29:05<1667::AID-IMMU1667>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zajonc DM, Maricic I, Wu D, Halder R, Roy K, Wong CH, Kumar V, Wilson IA. Structural basis for CD1d presentation of a sulfatide derived from myelin and its implications for autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1517–1526. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubetzki C, Thuillier Y, Galli A, Lyon-Caen O, Lhermitte F, Zalc B. Galactosylceramide: a reliable serum index of demyelination in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:407–409. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sela BA, Konat G, Offner H. Elevated ganglioside concentration in serum and peripheral blood lymphocytes from multiple sclerosis patients in remission. J Neurol Sci. 1982;54:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(82)90226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo T, Scott DD, Stewart SS, Kundu SK, Marcus DM. Antibodies to glycosphingolipids in patients with multiple sclerosis and SLE. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1984;174:455–461. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-1200-0_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilyas AA, Chen ZW, Cook SD. Antibodies to sulfatide in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;139:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamshiev A, Donda A, Prigozy TI, Mori L, Chigorno V, Benedict CA, Kappos L, Sonnino S, Kronenberg M, De Libero G. The alphabeta T cell response to self-glycolipids shows a novel mechanism of CD1b loading and a requirement for complex oligosaccharides. Immunity. 2000;13:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Battistini L, Fischer FR, Raine CS, Brosnan CF. CD1b is expressed in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;67:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(96)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager A, Kuchroo VK. Effector and regulatory T-cell subsets in autoimmunity and tissue inflammation. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar V, Sercarz E. Distinct levels of regulation in organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Life Sci. 1999;65:1523–1530. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Garra A, Steinman L, Gijbels K. CD4+ T-cell subsets in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:872–883. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jahng AW, Maricic I, Pedersen B, Burdin N, Naidenko O, Kronenberg M, Koezuka Y, Kumar V. Activation of natural killer T cells potentiates or prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1789–1799. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamoto K, Miyake S, Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature. 2001;413:531–534. doi: 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh AK, Wilson MT, Hong S, Olivares-Villagomez D, Du C, Stanic AK, Joyce S, Sriram S, Koezuka Y, Van Kaer L. Natural killer T cell activation protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1801–1811. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamura T, Miyamoto K, Illes Z, Pal E, Araki M, Miyake S. NKT cell-stimulating synthetic glycolipids as potential therapeutics for autoimmune disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:561–567. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanter JL, Narayana S, Ho PP, Catz I, Warren KG, Sobel RA, Steinman L, Robinson WH. Lipid microarrays identify key mediators of autoimmune brain inflammation. Nat Med. 2006;12:138–143. doi: 10.1038/nm1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, Nakagawa R, Sato H, Kondo E, Koseki H, Taniguchi M. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halder RC, Aguilera C, Maricic I, Kumar V. Type II NKT cell-mediated anergy induction in type I NKT cells prevents inflammatory liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2302–2312. doi: 10.1172/JCI31602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bischof F, Hofmann M, Schumacher TN, Vyth-Dreese FA, Weissert R, Schild H, Kruisbeek AM, Melms A. Analysis of autoreactive CD4 T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis after primary and secondary challenge using MHC class II tetramers. J Immunol. 2004;172:2878–2884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford F, Kozono H, White J, Marrack P, Kappler J. Detection of antigen-specific T cells with multivalent soluble class II MHC covalent peptide complexes. Immunity. 1998;8:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozono H, White J, Clements J, Marrack P, Kappler J. Production of soluble MHC class II proteins with covalently bound single peptides. Nature. 1994;369:151–154. doi: 10.1038/369151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schatz PJ. Use of peptide libraries to map the substrate specificity of a peptide-modifying enzyme: a 13 residue consensus peptide specifies biotinylation in Escherichia coli. Biotechnology (N Y) 1993;11:1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nbt1093-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arrenberg P, Maricic I, Kumar V. Sulfatide-mediated activation of type II natural killer T cells prevents hepatic ischemic reperfusion injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:646–655. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshimoto T, Bendelac A, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Defective IgE production by SJL mice is linked to the absence of CD4+, NK1.1+ T cells that promptly produce interleukin 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11931–11934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subramanian L, Blumenfeld H, Tohn R, Ly D, Aguilera C, Maricic I, Mansson JE, Buschard K, Kumar V, Delovitch TL. NKT cells stimulated by long Fatty acyl chain sulfatides significantly reduces the incidence of type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arrenberg P, Halder R, Dai Y, Maricic I, Kumar V. Oligoclonality and innate-like features in the TCR repertoire of type II NKT cells reactive to a beta-linked self-glycolipid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000576107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furlan R, Bergami A, Cantarella D, Brambilla E, Taniguchi M, Dellabona P, Casorati G, Martino G. Activation of invariant NKT cells by alphaGalCer administration protects mice from MOG35-55-induced EAE: critical roles for administration route and IFN-gamma. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1830–1838. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mars LT, Araujo L, Kerschen P, Diem S, Bourgeois E, Van LP, Carrie N, Dy M, Liblau RS, Herbelin A. Invariant NKT cells inhibit development of the Th17 lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6238–6243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809317106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang SH, Lee JP, Jang HR, Cha RH, Han SS, Jeon US, Kim DK, Song J, Lee DS, Kim YS. Sulfatide-reactive natural killer T cells abrogate ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1305–1314. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang G, Nie H, Yang J, Ding X, Huang Y, Yu H, Li R, Yuan Z, Hu S. Sulfatide-activated type II NKT cells prevent allergic airway inflammation by inhibiting type I NKT cell function in a mouse model of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L975–984. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00114.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halder RC, Jahng A, Maricic I, Kumar V. Mini review: immune response to myelin-derived sulfatide and CNS-demyelination. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:257–262. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, Peng J, Takaku S, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Kumar V, Berzofsky JA. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5126–5136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillessen S, Naumov YN, Nieuwenhuis EE, Exley MA, Lee FS, Mach N, Luster AD, Blumberg RS, Taniguchi M, Balk SP, Strominger JL, Dranoff G, Wilson SB. CD1d-restricted T cells regulate dendritic cell function and antitumor immunity in a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-dependent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8874–8879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033098100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Cho S, Ueno A, Cheng L, Xu BY, Desrosiers MD, Shi Y, Yang Y. Ligand-dependent induction of noninflammatory dendritic cells by anergic invariant NKT cells minimizes autoimmune inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;181:2438–2445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parekh VV, Wu L, Olivares-Villagomez D, Wilson KT, Van Kaer L. Activated invariant NKT cells control central nervous system autoimmunity in a mechanism that involves myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:1948–1960. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denney L, Kok WL, Cole SL, Sanderson S, McMichael AJ, Ho LP. Activation of invariant NKT cells in early phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis results in differentiation of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocyte to M2 macrophages and improved outcome. J Immunol. 2012;189:551–557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YG, Choisy-Rossi CM, Holl TM, Chapman HD, Besra GS, Porcelli SA, Shaffer DJ, Roopenian D, Wilson SB, Serreze DV. Activated NKT cells inhibit autoimmune diabetes through tolerogenic recruitment of dendritic cells to pancreatic lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2005;174:1196–1204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kojo S, Seino K, Harada M, Watarai H, Wakao H, Uchida T, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M. Induction of regulatory properties in dendritic cells by Valpha14 NKT cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:3648–3655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Venken K, Decruy T, Aspeslagh S, Van Calenbergh S, Lambrecht BN, Elewaut D. Bacterial CD1d-Restricted Glycolipids Induce IL-10 Production by Human Regulatory T Cells upon Cross-Talk with Invariant NKT Cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:2174–2183. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kadri N, Korpos E, Gupta S, Briet C, Lofbom L, Yagita H, Lehuen A, Boitard C, Holmberg D, Sorokin L, Cardell SL. CD4(+) type II NKT cells mediate ICOS and programmed death-1-dependent regulation of type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2012;188:3138–3149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brandl C, Ortler S, Herrmann T, Cardell S, Lutz MB, Wiendl H. B7-H1-deficiency enhances the potential of tolerogenic dendritic cells by activating CD1d-restricted type II NKT cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jack C, Ruffini F, Bar-Or A, Antel JP. Microglia and multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:363–373. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chastain EM, Duncan DS, Rodgers JM, Miller SD. The role of antigen presenting cells in multiple sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lassmann H, van Horssen J. The molecular basis of neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3715–3723. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeon SB, Yoon HJ, Park SH, Kim IH, Park EJ. Sulfatide, a major lipid component of myelin sheath, activates inflammatory responses as an endogenous stimulator in brain-resident immune cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:8077–8087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwiecinski J, Rhost S, Lofbom L, Blomqvist M, Mansson JE, Cardell SL, Jin T. Sulfatide attenuates experimental Staphylococcus aureus sepsis through a CD1d-dependent pathway. Infection and immunity. 2013;81:1114–1120. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01334-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Izhak L, Ambrosino E, Kato S, Parish ST, O’Konek JJ, Weber H, Xia Z, Venzon D, Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. Delicate balance among three types of T cells in concurrent regulation of tumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1514–1523. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]