Abstract

Objective:

Polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions are frequent and important among older people. Few clinical trials have evaluated systematic withdrawal of medications among older people. This small, open, study was conducted to determine the feasibility of a randomized controlled deprescribing trial.

Methods:

Ten volunteers living in the community (recruited by media advertising) and 25 volunteers living in residential aged-care facilities (RCFs) were randomized to intervention or control groups. The intervention was gradual withdrawal of one target medication. The primary outcome was the number of intervention participants in whom medication withdrawal could be achieved. Other outcomes measures were quality of life, medication adherence, sleep quality, and cognitive impairment.

Results:

Participants were aged 80 ± 11 years and were taking 9 ± 2 medications. Fifteen participants commenced medication withdrawal and all ceased or reduced the dose of their target medication. Two subjects withdrew; one was referred for clinical review, and one participant declined further dose reductions.

Conclusions:

A randomized controlled trial of deprescribing was acceptable to participants. Recruitment in RCFs is feasible. Definitive trials of deprescribing are required.

Keywords: ageing, deprescribing, polypharmacy prescriptions, treatment withdrawal

Background

Polypharmacy is common in older people [Weingart et al. 2005; Lazarou et al. 1998] and causes falls and confusion [Leipzig et al. 1999; Moore and O'Keeffe, 1999]. Adverse drug reactions are also a common cause of hospital admission, morbidity, and mortality in this population [Lau et al. 2005; Mannesse et al. 2000, 1997; Roughead et al. 1998].

Older patients often have multiple comorbidities, resulting in indications to prescribe several medicines. However, evidence supporting the efficacy of many drug classes in older patients is limited [Le Couteur et al. 2004]. In addition, adverse drug reactions and prescribing errors of omission and commission increase disproportionately as the number of drugs prescribed increases [Routledge et al. 2004]. Patients supplied with prescription drugs may also be taking over-the-counter or ‘complementary’ drugs which may further increase the likelihood of adverse interactions with prescribed medicines.

Some authors have attempted to define ‘high-risk’ prescribing by identifying questionable drug combinations, excessive treatment duration, and drugs that are relatively contraindicated in older people [Tamblyn et al. 1994]. Criteria for identifying potentially inappropriate drugs in older people have also been proposed [Fick et al. 2003]. However, these approaches rely on expert consensus and do not address the more fundamental problem that drugs are easy to start but apparently difficult to stop. Many guidelines describe the indications for initiating treatment but few guidelines advise on stopping treatment.

Reducing polypharmacy is difficult [Pitkala et al. 2001], but ‘back-titration’ of drug therapy is feasible in specific circumstances. Long-term withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs can be achieved in a proportion of patients [Nelson et al. 2002] and medication withdrawal is a component of effective falls prevention interventions [Campbell et al. 1999]. Although medications can be ceased safely in many patients, there is a risk of withdrawal reactions, symptom recurrence, or reactivation of underlying disease [Nelson et al. 2002; Graves et al. 1997]. This clinical equipoise indicates a need to study the process of drug withdrawal under controlled conditions.

This study is the first phase in work to test the hypothesis that phased reduction in dose or withdrawal of prespecified target drugs is feasible, safe and improves outcomes in older people. The present study is a pilot randomized controlled deprescribing study, conducted to inform design of subsequent definitive trials. The aim of the study was to determine the feasibility of a trial of reduction of dose or complete withdrawal of a list of drugs used for common chronic disorders among older people.

Methods

Trial design

STOPAT (Systematic Termination of Pharmaceutical Agents Trial) was an open, randomized controlled trial.

Setting

In July 2007, we advertised for volunteers in local media. In December 2009, due to limited success in attracting community participants, recruitment was expanded to include residential aged-care facilities (RCFs) in the Perth metropolitan area that had participated in previous research [Somers et al. 2010].

Participants

The inclusion criteria were:

participant taking at least one drug included in the target drug list (Table 1);

participant has stable chronic disease with respect to the medication targeted for withdrawal;

patient reports at least one negative symptom ascribable to the drug therapy (effects specific to drug class, or possible adverse effects such as falls, confusion, malaise and nausea), or is taking more than five drugs concurrently;

aged greater than 60 years;

treating physician agrees to randomization.

Table 1.

Target drug list.

| Drug or drug class | Indicated condition | Indication for dose reduction or withdrawal | Criterion for benefit | Criteria for withdrawal from trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antihypertensive agents | Hypertension only | BP <150/100 mmHg PLUS side effects reasonably ascribable to the drug. This value allows inclusion of patients who have possible white coat effects, and this should be demonstrated before inclusion if clinic BP >140/90 mmHg | Symptomatic relief; no increase in BP; improved QOL | BP >150/100 mmHg |

| Same class used for renal protection in diabetes and other conditions, heart failure, or in cardiovascular ‘high risk’ (e.g. HOPE Study) indications | Postural dizziness, postural hypotension or falls | Symptomatic relief; normotension; improved QOL | Worsening renal function (>20% rise in Cr), symptoms of CHF, vascular event | |

| Anti-anginals | Classical angina or documented ischaemic disease (angiography, myocardial perfusion study etc.) | On >1 agent for this indication and angina attack rate <1/week, with no history of acute MI | Symptomatic relief; improved QOL; no increase in anginal attack rate | Increase in angina attack rate or development of unstable angina |

| Diuretics | Any indication except CHF or hypertension (e.g. peripheral oedema without CHF) | Clinically stable | Symptomatic relief; improved QOL | Worsening symptoms and signs of heart failure |

| NSAIDs | Pain with or without an inflammatory component | Stable symptoms for three months. Side effects | Symptomatic relief; improved QOL | Deterioration in pain score |

| COX-2 inhibitors | As above | Stable symptoms for three months. Absence of increased risk of GI haemorrhage or other side effects | Symptomatic relief; improved QOL | Deterioration in pain score |

BP, blood pressure; CHF, congestive heart failure; COX, cyclooxygenase; Cr, creatinine; GI, gastrointestinal; MI, myocardial infarction; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; QOL, quality of life.

The exclusion criteria were:

patient is taking warfarin.

Randomization

Participants were openly assigned to intervention or control groups using a randomization table, prospectively created using a computerized random number generator.

Intervention

A systematic deprescribing intervention was implemented (comprising a structured approach to withdrawal of medications from various classes). A list of target drugs was prospectively defined (Table 1) comprising antihypertensive therapy, anti-anginal therapy, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase (COX-2) inhibitors. Participant Intervention Group information sheets were drafted for each drug class, providing the rationale for withdrawal of therapy and general advice to participants. If a participant was taking multiple target drugs, a single target drug was identified for withdrawal in discussion with the participant. In addition to the Participant Information sheet and Intervention Group Sheet, all participants were provided with a record of their study participation documenting their target drug and any changes made to therapy. Participants were asked to record any perceived adverse symptoms on the record sheet. Dose reductions were made at 2-weekly intervals with provision for curtailment or extension according to clinical requirements.

Follow up and clinical outcomes

The following outcomes were assessed at baseline and at each fortnightly visit: quality of life, measured using the SF-36 [Ware and Sherbourne, 1992] and EQ5D visual analogue scale [Rabin and de Charro, 2001]; medication adherence, assessed with the Medication Adherence Scale [Morisky et al. 1986]; sleep quality, assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [Carpenter and Andrykowski, 1998]; and cognitive function, assessed using the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) [Folstein et al. 1975].

Sample size and statistical methods

This study was conceived as a pilot trial. The primary outcome of interest was thus feasibility of the protocol and no formal power calculation was undertaken. A goal of 40 participants was set, to allow assessment of feasibility. Baseline and clinical outcome data are presented descriptively, with chi square tests for categorical data and t-tests to compare parametric data.

Ethical approval

All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Royal Perth Hospital. The general practitioner (GP) and treating specialist, if requested by the GP, of all patients randomized to withdrawal of the target medication were contacted and provided agreement for their patient to participate in the trial. This study is registered in the ANZCTR (ACTRN12610000865011).

Results

Recruitment and baseline data

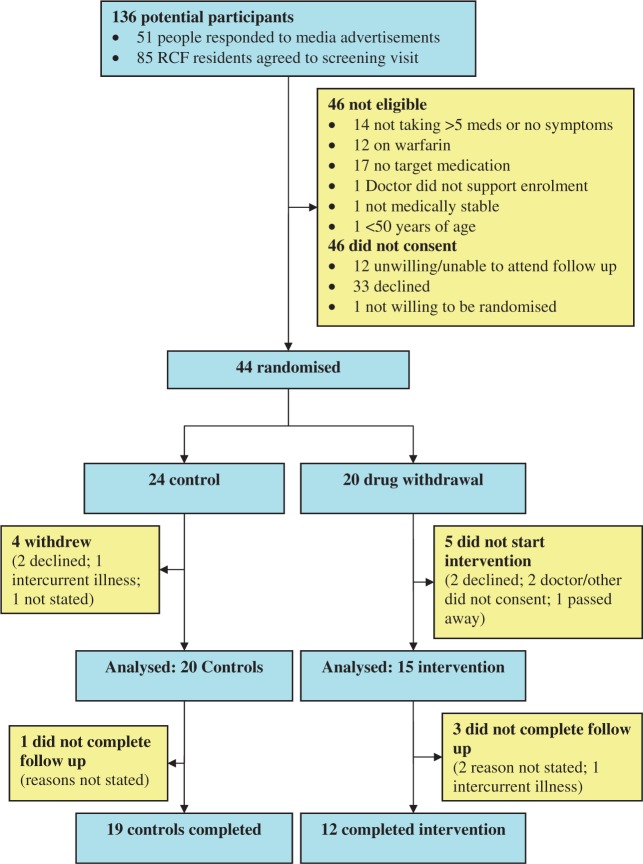

There were 51 people who responded to media advertising between October 2007 and October 2008. Of these, 37 people were ineligible or did not consent to study participation. The need to travel to the university hospital campus for regular follow up was a frequent barrier to participation. Some participants were also unwilling to be randomized. There were 85 RCF residents who consented to screening at their facility between January and April 2010, leading to 30 enrolments. Among RCF residents, declining to participate was the most common reason for nonenrolment (n = 31), followed by absence of target medication (n = 13). The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1. Participants had a mean age of 80 ± 11 years and were taking 9 ± 2 medications. The mean number of visits was 4 ± 1.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. Meds, medications; RCF, residential aged-care facility.

Feasibility of deprescribing

Of the 15 participants who commenced medication withdrawal, all ceased or reduced the dose of their target medication. In 11 participants, this proceeded satisfactorily. Two withdrew, one was referred for clinical review due to hypertension, and one participant declined further reductions in analgesic therapy. Table 2 shows descriptive details of the 15 participants randomised to medication withdrawal.

Table 2.

Outcomes for participants in withdrawal arm.

| Class – medication; target symptom (if present) | Withdrawal achieved? | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community dwelling participants | |||

| 1 | Diuretic – spironolactone; gynaecomastia | Yes | Remained normotensive; target symptom improved |

| 2 | Antihypertensive – amlodipine; light headedness | Yes | Remained normotensive; target symptom improved |

| 3 | Antihypertensive – metoprolol; tiredness | Yes | Remained normotensive; target symptom improved |

| 4 | Antihypertensive – lercanidipine; erectile dysfunction | Yes | Hypertensive – clinical review recommended; no change in target symptom |

| 5 | Antihypertensive – perindopril | Yes | Remained normotensive; withdrew (reason not stated) |

| Residential care facility participants | |||

| 6 | Antihypertensive – metoprolol | Dose reduced | Withdrew (intercurrent illness – diagnosed malignancy) |

| 7 | Analgesic – celecoxib | Dose reduced | Arthritic pain manageable, declined further dose reductions |

| 8 | Analgesic – meloxicam | Yes | Felt improved |

| 9 | Antihypertensive – perindopril | Yes | Remained normotensive |

| 10 | Diuretic – frusemide | Dose reduced | |

| 11 | Antianginal - perhexiline | Yes | |

| 12 | Antihypertensive - tensig | Dose reduced | Remained normotensive |

| 13 | Diuretic – frusemide | Yes | |

| 14 | Diuretic – frusemide | Yes | |

| 15 | Diuretic – spironolactone | Yes | |

Clinical outcomes

Data from 35 participants (n = 14 men) were analysed. Outcome assessment tools proved acceptable to participants. Table 3 shows data from the baseline and final followup assessments.

Table 3.

Participant data at baseline and follow up.

| Control N = 20 | With- drawal N = 15 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Age | 79 ± 12 | 81 ± 9 | 0.66 | |

| RCF | 15 (75%) | 10 (67%) | 0.59 | |

| Female | 13 (65%) | 8 (53%) | 0.49 | |

| MMSE | 27 ± 3 | 26 ± 2 | 0.74 | |

| Number of medications | 10 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 0.15 | |

| Visits | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 | 0.10 | |

| Final follow up | ||||

| SF-36 | 74 ± 23 | 69 ± 18 | 0.50 | |

| EQ5D | 66 ± 26 | 75 ± 25 | 0.32 | |

| Sleep quality | 5 ± 4 | 6 ± 2 | 0.18 | |

| MMSE | 27 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | 0.83 | |

| Medication Adherence (MA) | 0 | 16 (80%) | 11 (79%) | 0.17 |

| 1 | 3 (15%) | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 2 (14%) | ||

| 4 | 1 (5%) | 1 (7%) | ||

Results are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). EQ5D, EuroQol visual analogue scale; MA, adherence to medication; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; RCF, residential aged-care facility; SF-36, short-form-36 health survey.

Discussion

Main findings and implications

While other investigators have withdrawn single classes of medication, to the knowledge of the investigators this is the first randomised trial of systematic deprescribing. The sample size of this pilot study is small, but provides valuable information to inform design of definitive trials. Recruitment of community volunteers to the pilot was difficult as passive recruitment strategies (such as advertising of the study to clinical and pharmacy staff) were largely unsuccessful. Future trials would benefit from resources to support systematic screening of defined populations (such as primary care populations, defined inpatient populations, or residential care populations). The investigators used media advertising, but this may introduce a more substantial volunteer bias than systematic screening, or random invitation, within defined populations. Focusing on populations with high levels of frailty and comorbidity, such as care facility residents would be preferable, given the genuine uncertainty regarding the balance of benefits and harms of prescribed therapies in these populations. Uncertainty is greatest with respect to treatments prescribed for prognostic benefit, such as statins, and these agents should be a focus of future trials. Given the importance of assessing the safety of withdrawing agents prescribed for prognostic benefit, future larger trials should incorporate assessment of clinical outcomes as well as participants’ perceptions of their wellbeing.

Results in context of other studies

Studies of the withdrawal of specific classes of medication have been systematically reviewed [Iyer et al. 2008]. However, there are few data regarding systematic deprescribing. There is evidence from controlled, although nonrandomized trials, that deprescribing is associated with a substantial mortality benefit among frail older people [Garfinkel et al. 2007]. The present data indicate the feasibility of a randomized controlled trial of deprescribing among frail older people. Thus, future randomized deprescribing trials could be designed to test the hypothesis that deprescribing reduces mortality in that population.

Strengths and limitations

The randomized design is a major strength of this pilot study, and allows conclusions to be reached regarding the acceptability to participants (and their physicians) of a randomized controlled trial of systematic deprescribing. However, the small number of participants is a major limitation of this study, and limits the generalizability of the findings. There is also potential for random error to influence the findings of small studies.

Conclusions

A randomized controlled trial of medication withdrawal was acceptable to participants. Recruitment of older care facility residents is feasible. Definitive trials of deprescribing are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr Rhana Arnold, Ms Sarah Carson and Ms Kerri Schoenaeur, who assisted with collection of data.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Royal Perth Hospital Medical Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Campbell A.J., Robertson M.C., Gardner M.M., Norton R.N., Buchner D.M. (1999) Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 47: 850–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J.S., Andrykowski M.A. (1998) Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. J Psychosomatic Res 45: 5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick D.M., Cooper J.W., Wade W.E., Waller J.L., Maclean J.R., Beers M.H. (2003) Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 163: 2716–2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel D., Zur-Gil S., Ben-Israel J. (2007) The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J 9: 430–434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves T., Hanlon J.T., Schmader K.E., Landsman P.B., Samsa G.P., Pieper C.F., et al. (1997) Adverse events after discontinuing medications in elderly outpatients. Arch Intern Med 157: 2205–2210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S., Naganathan V., McLachlan A.J., Le Couteur D.G. (2008) Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 25: 1021–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau D.T., Kasper J.D., Potter D.E.B., Lyles A., Bennett R.G. (2005) Hospitalization and death associated with potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 165: 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarou J., Pomeranz B.H., Corey P.N. (1998) Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 279: 1200–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Couteur D.G., Hilmer S.N., Glasgow N., Naganathan V., Cumming R.G. (2004) Prescribing in older people. Aust Fam Physician 33: 777–781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipzig R.M., Cumming R.G., Tinetti M.E. (1999) Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 47: 30–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannesse C.K., Derkx F.H., de Ridder M.A., Man in 't Veld A.J., van der Cammen T.J. (1997) Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients as contributing factor for hospital admission: cross sectional study. BMJ 315: 1057–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannesse C.K., Derkx F.H., de Ridder M.A., Man in 't Veld A.J., van der Cammen T.J. (2000) Contribution of adverse drug reactions to hospital admission of older patients. Age Ageing 29: 35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A.R., O'Keeffe S.T. (1999) Drug-induced cognitive impairment in the elderly. Drugs Aging 15: 15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D.E., Green L.W., Levine D.M. (1986) Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 24: 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M.R., Reid C.M., Krum H., Muir T., Ryan P., McNeil J.J. (2002) Predictors of normotension on withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs in elderly patients: prospective study in second Australian national blood pressure study cohort. BMJ 325: 815–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkala K.H., Strandberg T.E., Tilvis R.S. (2001) Is it possible to reduce polypharmacy in the elderly? A randomised, controlled trial. Drugs Aging 18: 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin R., de Charro F. (2001) EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 33: 337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughead E.E., Gilbert A.L., Primrose J.G., Sansom L.N. (1998) Drug-related hospital admissions: a review of Australian studies published 1988–1996. Med J Aust 168: 405–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge P.A., O'Mahony M.S., Woodhouse K.W. (2004) Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57: 121–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers M., Rose E., Simmonds D., Whitelaw C., Calver J., Beer C. (2010) Quality use of medicines in residential aged care. Aust Fam Physician 39: 413–416 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamblyn R.M., McLeod P.J., Abrahamowicz M., Monette J., Gayton D.C., Berkson L., et al. (1994) Questionable prescribing for elderly patients in Quebec. CMAJ 150: 1801–1809 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J.E., Jr, Sherbourne C.D. (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30: 473–483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingart S.N., Gandhi T.K., Seger A.C., Seger D.L., Borus J., Burdick E., et al. (2005) Patient-reported medication symptoms in primary care. Arch Intern Med 165: 234–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]