Abstract

Purpose

Tumour hypoxia affects cancer biology and therapy-resistance in both animals and humans. The purpose of this study was to determine whether EF5 ([2-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoropropyl)-acetamide]) binding and/or radioactive drug uptake correlated with single-dose radiation response in 9L gliosarcoma tumours.

Materials and methods

Twenty-two 9L tumours were grown in male Fischer rats. Rats were administered low specific activity 18F-EF5 and their tumours irradiated and assessed for cell survival and hypoxia. Hypoxia assays included EF5 binding measured by antibodies against bound-drug adducts and gamma counts of 18F-EF5 tumour uptake compared with uptake by normal muscle and blood. These assays were compared with cellular radiation response (in vivo to in vitro assay). In six cases, uptake of tumour versus muscle was also assayed using images from a PET (positron emission tomography) camera (PENN G-PET).

Results

The intertumoural variation in radiation response of 9L tumour-cells was significantly correlated with uptake of 18F-labelled EF5 (i.e., including both bound and non-bound drug) using either tumour to muscle or tumour to blood gamma count ratios. In the tumours where imaging was performed, there was a significant correlation between the image analysis and gamma count analysis. Intertumoural variation in cellular radiation response of the same 22 tumours was also correlated with mean flow cytometry signal due to EF5 binding.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first animal model/drug combination demonstrating a correlation of radioresponse for tumour-cells from individual tumours with drug metabolism using either immunohistochemical or non-invasive techniques.

Keywords: EF5, tumour hypoxia, 9L-gliosarcoma, predictive assay, non-invasive molecular imaging

Introduction

The importance of assays for hypoxia in tumours has been persuasively demonstrated both in understanding their biological and molecular characteristics and their response to several treatment modalities (reviewed in Arbeit et al. 2006, Evans & Koch 2003, Vaupel & Mayer 2007). Hypoxic tumour cells are particularly refractory to radiation therapy due to lack of oxidation of radiation-induced free radicals on critical target molecules such as DNA (Koch 1983). Since hypoxia is known to vary widely between human tumours with otherwise similar characteristics (Brizel et al. 1996, Fyles et al. 1998, Hockel et al. 1993, Nordsmark et al. 1996) its accurate measurement should play a role in the optimisation of individualised treatment using anti-hypoxia therapies. In addition to this inter-tumoural variation in hypoxia, the distribution of hypoxic tumour cells can also vary widely within an individual tumour on both a microscopic and macroscopic level (Evans et al. 2000, Evans et al. 2008, Jenkins et al., 2000). The ability to determine the intra-tumoural distribution of hypoxia could be used to direct radiation therapy – for example by intensity modulation or particle beam ‘dose painting’ (Chao et al. 2001, Flynn et al. 2008, Grosu et al. 2007, Thorwarth et al. 2008). Non-invasive assays are critically required for this purpose.

Several non-invasive methods have been proposed to image hypoxia (MRI (magnetic resonance imaging); phosphorescence quenching; various measures of blood flow and oxygenation, glucose uptake, etc.) but the ones most closely linked to actual tissue pO2 rather than vascular oxygen supply include isotopically-labelled 2-nitroimidazoles and metal chelates. Cu-ATSM (Cu(II)-diacety-bis(N4-methylthiosemi-carbaxone) exemplifies the latter and clinical studies with this compound have shown a promising correlation with tumour grade and early response in cancer of the uterine cervix (Dehdashti et al., 2003). F-18-labelled fluoromisonidazole (FMISO; 1-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-3-fluoro-2-propan-2-ol) is the prototype for drugs of the 2-nitroimidazole class (Koh et al. 1991). Several human trials with this compound have been performed and two have shown predictive value for patient outcome (Eschmann et al. 2005, Thorwarth et al. 2005). A recent study in head and neck cancer has demonstrated both predictive and prognostic capability (Rischin et al. 2006).

Ballinger has reviewed several perceived problems with hypoxia-imaging drugs (Ballinger 2001) and these problems have spawned the development of several new analogs (see (Krohn et al. 2008 for review) including a separate group of nucleoside-conjugated 2-nitroimidazoles (Chapman et al. 2001). One reason for this continuing development is the imperfect correlation of response prediction in clinical studies. Thus, although the significance (p value <0.05) of correlation for outcome versus drug uptake has been established, sensitivity and specificity of the assays has significant room for improvement. This problem is amplified in pre-clinical studies since there are no existing data exemplifying the therapeutic goal of predicting response in individual animal tumours. The absence of such data may be associated with the relatively uniform characteristics and responses of most animal tumour models. Alternatively, factors related to drug development and use, that are, as yet, poorly understood may be involved.

In light of these and other considerations, EF5 (2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoro propyl)-acetamide) was specifically designed as a hypoxia marker, its structure incorporating several characteristics derived in former biochemical and pharmacological studies (Koch et al. 2001). Thus, EF5’s structure was based upon the known biological stability of etanidazole (Coleman et al. 1984) coupled with the strength of C-F bonds, incorporated into the sidechain to allow various detection modalities (Koch 2002). EF5 is quite lipophilic (octanol:water partition coefficient 5.7 versus 0.4 for FMISO) whereas almost all other hypoxia markers under current development are more hydrophilic than FMISO. The rationale behind this reversal in drug development concept was that it might be better to emphasise uniform biodistribution (a characteristic of moderately lipophilic drugs) rather than rapid renal elimination (a characteristic of hydrophilic drugs) (Workman 1980). Neurotoxicity, a side-effect of the therapeutic use (radiosensitisation or hypoxic-cell killing) of lipophilic 2-nitroimidazoles (Coleman et al. 1987) was not a concern because diagnostic drug levels (compared with therapuetic drug levels) should not pose a toxicity hazard.

EF5 was first used as an imaging agent for invasive assays, using antibodies to detect drug-adducts bound to cellular macromolecules (Lord et al. 1993). These antibodies were the first monoclonals produced for such a purpose and they were conjugated to Cy3 or Cy5 allowing a single antibody detection system. The ‘Cy-dyes’ (carboxymethylin-docyanine) have very stable characteristics as described by Waggoner (Southwick et al. 1990). Despite a relatively high affinity and specificity, the in vivo drug concentration required for single-antibody detection was much higher (50–100 μM average tissue concentration) than typically used for nuclear medicine-based assays (pico- to nano-molar). EF5 binding (as measured by flow cytometry after immunohistochemical staining) was the first assay correlating with endogenous variations in tumour-cell radiation response in an animal model (9L gliosarcoma (Evans et al. 1996)). It has retained this distinction (Kavanagh et al. 1999, Siim et al. 1997) although several assays, including EF5 binding, have been shown to correlate with changes induced by acute modulation of blood flow or tissue oxygenation (Horsman et al. 1993, Lee et al. 1996).

In this report we demonstrate that uptake of 18F-labelled EF5, as measured by total radioactive drug (bound plus unbound) in tumour versus muscle or blood correlates with cellular radiation response for the 9L tumour model.

Methods

Cell and tissue source

Cells (9LC6) were originally obtained from Dr Ken Wheeler (Wallen et al. 1980). They were thawed from frozen stock at 3–4 month intervals. Growth in tissue culture used MEM (minimal essential medium) plus 12.5% (v/v) newborn calf serum under standard conditions (culture reagents from GIBCO, Grand Island, New York, USA). Animal procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee. Fischer 344 male rats were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA, USA) at a size of 150–200 g (4–6 weeks of age). Sub-cutaneous tumours were initiated in the shoulder region using ~400,000 cells in 50 μl of serum-free medium. Tumours grown from cells were described as ‘passage zero’ (P0). Tumour pieces (~5 mg) were transplanted into new hosts to derive later passage tumours. Thus, P1 tumours were derived from pieces of a P0 tumour, etc. The tumour pieces used for transplantation could be derived from fresh tissue, but it was also possible to store them within sealed glass vials in liquid nitrogen. For the latter case, freezing medium was buffered (25 mM HEPES; 4-(hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazi-neethanesulfonate) MEM containing 5% dimethyl-sulfoxide (all chemicals from SIGMA, St. Louis, MO, USA). We have found that mid passage 9L tumours (P4–P7) have well-developed blood vessels and stroma, similar to the architecture of human tumours. These tumours have considerable inter-tumoural variation in tissue-oxygenation and radiation-resistance. This variation was considered to be favorable since it also mimics the characteristics of human tumours (Evans et al. 1996). We have found that the cell yield, plating efficiency and in vitro radiation response of cells derived from tumours do not change from low to mid passage (Evans et al. 1996). At a size of 1–3 g, mid-passage tumours were assessed for tissue 18F-EF5 uptake (by gamma count) as well as EF5 binding (by flow cytometry) and radiation response (by colony formation) of tumour-derived cells. In a subset of animals (depending on availability of the clinical camera) 18 F-EF5 PET images were also obtained.

Synthesis and purification of 18F-EF5

18F-EF5 was synthesised by electrophillic fluorination of an allyl precursor as previously described (Dolbier et al. 2001). This process uses fluorine gas (0.1%) in neon carrier to incorporate both atoms of fluorine at the allyl double bond. Radioactive fluorine gas was made using the 20Ne(d,α)18F reaction. This is an inherently low specific activity (SA) reaction because of the need for a relatively high volume of high pressure (300 psi) gas (maximum SA ~ 1000 mCi/mmole). Since this was so much lower than that using typical nucleophilic reactions it was decided to lower the SA still further, by addition of unlabelled EF5, to provide the standard drug dose used for immunohistochemical studies (whole body equivalent of 100 μM – see Evans et al. 1996). This allowed the simultaneous measurement of uptake (total bound plus unbound drug) based on gamma counts, and binding (bound drug only) based on immunohistochemistry. The 100 μM drug concentration is similar to that used for immunohistochemical studies in humans but is much lower than needed for modifications to hypoxic-cell radioresistance (Koch et al. 2001).

Experimental studies

Tumour-bearing rats were anesthetised for the entire experimental period (3 h following intravenous drug injection) using 1.5–2.5% isoflurane in air (varied as required to maintain a uniform respiration rate). Body temperature (measured by rectal probe) was found to be maintained near 37 °C by positioning the animal on a temperature-controlled water pad. In addition to the specific tumour measurements, some of the animals were imaged, initially utilising a camera optimised for human head studies (PENN G-PET). More recent experiments employed a micro-PET instrument (Philips Mosaic; Philips Medical Systems, Philadelphia, PA, USA). While on the PET scanner bed, temperature was maintained by situating the animal within a styrofoam mold, covered by a thin silicone-encased heating element if necessary.

Labelled and unlabelled EF5 were combined (solvent: water plus 2.4% ethanol with 5% dextrose) and injected by tail vein to provide the equivalent of 100 μM drug whole body (30 mg/kg). For a subset of animals, PET images were collected at roughly 10, 30 and 120–150 minutes following drug injection (a typical radioactive drug dose of 100–200 microcuries per rat). At 170 minutes post drug injection the rats were moved to an X-ray unit (Philips RT250) and placed on a 37 °C gel with tumour ‘up’. Their tumours were irradiated to a central dose of 17 Gy (225 kVp, 0.5 mm Cu filter). Based on thermoluminescent dosimeters or film the radiation field is flat across the boundaries of tumours of this size. Since the tumours were to be removed immediately, no shielding of the rest of the animal was employed. At 180 minutes post drug injection the skin overlying each tumour was removed and the tumour was photographed with a Polaroid or digital camera. The tumours were then resected from the underlying musculature, coarsely minced on a cooled plastic dish (with no additional liquid) and the resulting pieces mixed. This has the purpose of averaging intratumoural spatial variations in binding or radio-resistance (Jenkins et al. 2000). Representative portions of the tumour mince were (i) added to a pre-weighed tube, which was then re-weighed, for gamma count determination, and (ii) added to an enzyme cocktail for cell dissociation. Approximately 300 mg of tissue was used for each purpose, with residual tissue discarded. Cells from the enzyme cocktail dissociation (Evans et al. 1996) were counted (hemocytometer and Z1 Coulter- Coulter Corp., Miami, FL. USA) diluted and plated to determine colony-forming ability. The fraction of cells forming colonies was calculated after a growth time of two weeks at 37 ° under standard incubation conditions. A portion of the cells from the tissue dissociated with enzymes was also fixed and stained for EF5 adducts (using Cy5-conjugated anti-EF5 antibodies) as previously described (Evans et al. 1996, Koch 2002, Koch et al. 1995).

Blood and normal muscle (opposite shoulder) were collected at the time of tumour resection. Portions of these tissues were also added to pre-weighed tubes, re-weighed and assessed for gamma counts. The gamma counts were collected on a Packard AutoGamma (Packard Instrument Co, Meriden, CT, USA) and compared with ~1% of injected dose, the latter established by weighing an appropriate sample of the initial injection solution into a tube for the gamma counter. Since drug was injected via an indwelling tail catheter, the estimation of injected drug was possible within the accuracy of the 3 ml syringe used (<±1%). Determination of average tumour to muscle ratio, as measured by images from the G-PET camera, was accomplished by selecting regions of interest and then collecting the average voxel density information, using the software package ‘PetView’ (Philips) as described previously (Karp et al. 2003, Ziemer et al. 2003).

Assessment of EF5 binding in the disaggregated tumour cells was assessed by Flow Cytometry using a FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) equipped with a red laser. The fluorescence signal of the immunostained tumour cells (‘Regular Stain’ or RS) was measured on an absolute scale standardised by cells with a known concentration of EF5 adducts. Absolute adduct concentration was determined by acid-precipitable uptake of 14C-labelled EF5 (drug, labelled on the C2 position, was made by Stanford Research International, Stanford, CA, USA – (Koch 2002, Koch et al. 1995). On this scale, 3 ×10−4 picomole of EF5 adducts per cell gives a fluorescence value of 1200 (cytometer scale from 1–10,000). Non-specific staining by the antibody was determined by the procedure termed ‘Competed Stain’ or CS, whereby authentic EF5 was added to the antibody and rinsing solutions to block the antibody’s specific binding sites (Koch 2008). The CS signal is roughly 100-fold less than the maximum binding associated with RS labelling. Mean flow cytometry signal was obtained by subtracting the mean values of CS from RS values.

Statistical assessment

Results were plotted using GraphPad Prism® (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) and comparisons between parameters were assessed using standard linear regression. Results were considered significant at a p value of 0.05.

Results

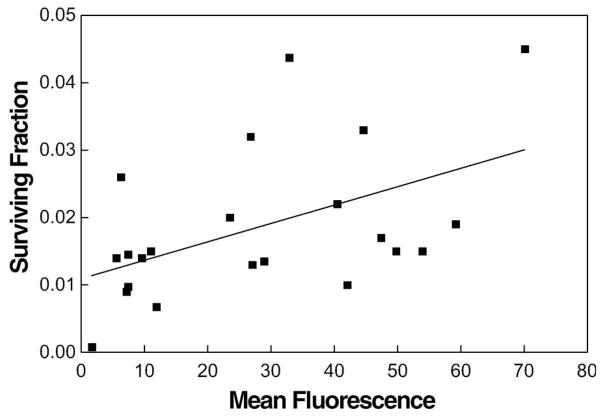

For the 22 tumours studied, a comparison of cell surviving fraction at 17 Gy with mean flow cytometry signal confirmed our prior experience with this model (Figure 1; Evans et al. 1996). In the earlier study, we used a more complex flow cytometry analysis with emphasis on cells with intermediate rather than maximal EF5 binding. However, in the present study we used a much simpler approach (mean fluorescence of RS tumour cells, after subtraction of mean fluorescence of the CS signal) to facilitate comparison with average EF5 uptake, using gamma counts. Surviving fraction was significantly correlated with mean flow cytometry signal (r2 = 0.248, p = 0.019).

Figure 1.

Surviving fraction of cells dissociated and plated from individual 9L tumours was significantly correlated with the mean EF5 binding of the same cells (n = 22; r2 = 0.248; p = 0.019). For each point, a tumour-bearing animal was administered EF5 (30 mg/kg, mixed unlabelled plus 18F-labelled) 3 h before the tumour was irradiated with 17 Gy (continuous isoflurane anesthesia). The tumour was removed and minced and cells dissociated from a portion of the mince. Some of the resulting cells were plated for colony formation and others were fixed, stained for EF5 adducts, and analysed by flow cytometry using a calibrated scale. In this and subsequent figures, the surviving fraction was not corrected for the average plating efficiency of cells from non-irradiated tumours (15–35%).

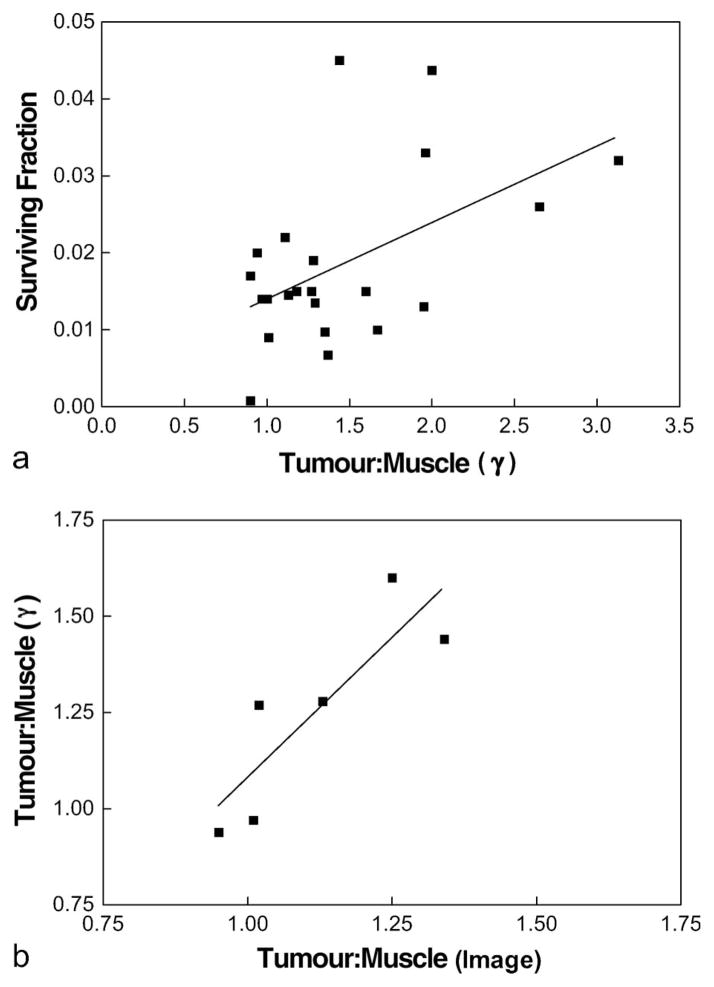

Similarly, surviving fraction at 17 Gy was significantly correlated with tissue gamma counts (tumour:muscle ratio – Figure 2a; r2 = 0.263, p = 0.015). For the six tumours also assessed by PET imaging (using the lower-resolution camera – Penn G-PET) a good correlation between tumour:muscle ratios using either direct gamma counts or average voxel values in regions of interest from the PET images was found (Figure 2b; r2 = 0.735, p = 0.029). The absolute values of the gamma count ratios were larger than those for average voxel values as a result of partial volume effects and also because the images were taken at 120–150 minutes, whereas the gamma counts were obtained after tissue collection at 180 minutes.

Figure 2.

(a) Surviving fraction of cells dissociated and plated from individual 9L tumours was significantly correlated with the mean 18F-EF5 uptake, determined by gamma counts. For each point, a tumour bearing animal was administered EF5 (30 mg/kg, mixed unlabelled plus 18F-labelled) 3 h before the tumour was irradiated with 17 Gy (continuous isoflurane anesthesia). The tumour was removed and minced cells dissociated from a portion of the mince (as described in Figure 1) and gamma counts determined from another portion of the mince. The gamma counts were normalised by comparing the cpm/mg of tumour tissue versus the cpm/mg of muscle (n = 22; r2 = 0.263; p = 0.015). (b) For 6 tumours imaged by the PENN G-PET scanner, there was a significant correlation between the tumour:muscle ratio, determined from the PET image, and tumour:muscle ratio, determined from samples assayed by gamma counts (n = 6; r2 = 0.735; p = 0.029).

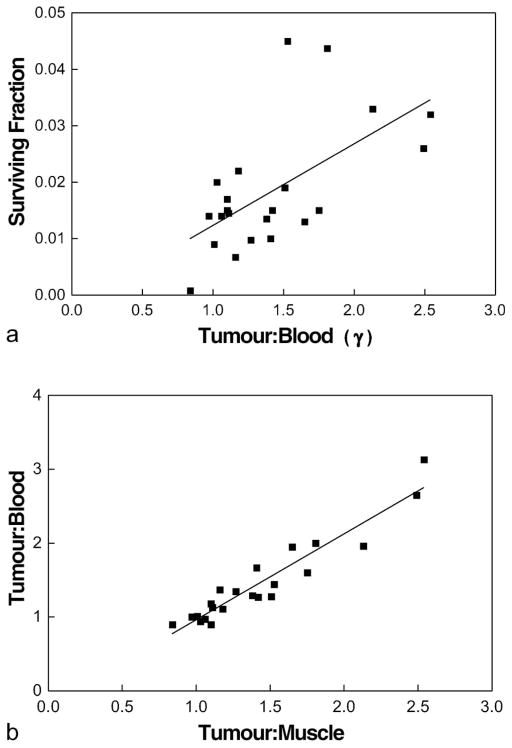

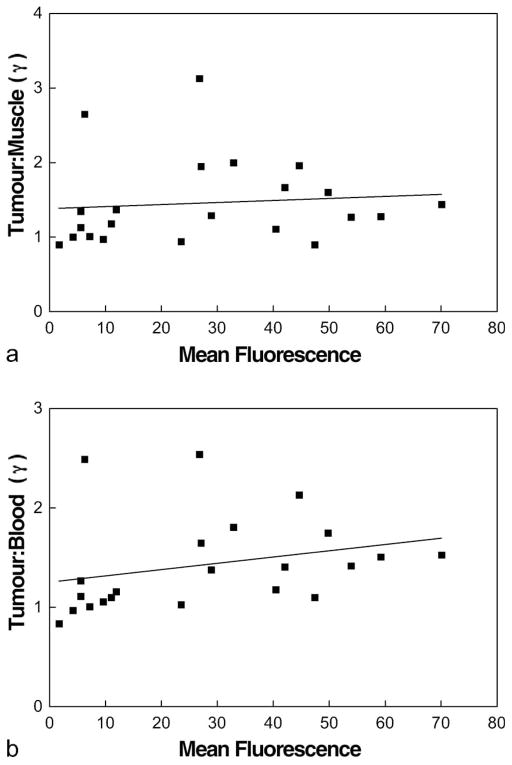

The best correlation with surviving fraction at 17 Gy was found for tumour:blood ratio (Figure 3a; r2 = 0.371, p <0.003), even though there was a very close relationship between gamma-count ratios of tumour:muscle and tumour:blood (Figure 3b; r2 = 0.90, p <0.0001). This may reflect small variations in actual muscle uptake or drug biodistribution. Even though mean flow cytometry signal and tumour to normal tissue gamma count ratio were each significantly correlated with surviving fraction at 17 Gy, the two measures of EF5 metabolism did not significantly correlate with each other (Figure 4a,b) – see discussion.

Figure 3.

(a) Surviving fraction of cells dissociated and plated from individual 9L tumours was significantly correlated with the mean 18F-EF5 uptake, determined by gamma counts. For each point, a tumour-bearing animal was administered EF5 (30 mg/kg, mixed unlabelled plus 18F-labelled) 3 h before the tumour was irradiated with 17 Gy (continuous isoflurane anesthesia). The tumour was removed and minced cells dissociated from a portion of the mince (as described in Figure 1) and gamma counts determined from another portion of the mince. The gamma counts were normalised by comparing the cpm/mg of tumour tissue versus the cpm/mg of blood (n = 22; r2 = 0.371; p <0.003). (b) For the 22 tumours studied, there was a very strong correlation between tumour:blood and tumour:muscle (n = 22; r2 = 0.90; p <0.0001). The small differences relative uptake in muscle compared to blood may reflect very modest hypoxia in the muscle, independent of tumour, since tumour:blood ratio provided the best estimate of relative radioresistance (i.e., compare Figure 2a versus Figure 3a).

Figure 4.

For the 22 tumours studied, there was no significant relationship between the mean flow cytometry signal, determined by EF5 binding and tumour to muscle (a) or tumour:blood (b) ratios determined by gamma counts measuring 18F-EF5 uptake.

The initial PET images for this study were derived from a PET camera not optimised for rodent work. With this device (Penn G-PET) the voxel size was about 64 mm3 and realistically it was not possible to observe 1–3 g tumours unless the average tumour: muscle ratio of counts, as determined by gamma counter, exceeded 1.4. The present microPET camera (Penn A-PET; Philips Mosaic) (Surti et al. 2005) has a much better spatial resolution (<8 mm3) and is easily able to identify assymetries in tumour shape or drug uptake even under conditions where the tumour:muscle uptake ratio was less than one. Such regions had not previously been observed with the lower resolution camera. In two tumours, we observed such hypo-dense regions using the Mosaic camera. The first involved a tumour with considerable central necrosis (occurs very rarely in the 9L model). The early (10 min –Figure 5a) image indicated slow perfusion of drug into this region. In the late image from the same animal (150 min – Figure 5b) the hypoxic areas near the necrosis led to an overall development of uptake, but the contrast was diminished by partial volume effects (Figure 5). In contrast, a second tumour had an adjacent hematoma. The relatively stagnant blood in this volume also appeared subjectively (10 min image) as a hypodense region which continued to show hypodensity throughout the imaging time of the study (not shown).

Figure 5.

Sample images from the Philips MOSAIC scanner. Upper panels: planar and orthogonal views (transaxial, sagital, coronal) at 10 minutes following drug injection of an animal whose tumour had a large central necrosis. Lower panels: similar views of the same animal but at 150 minutes following drug injection. Note that partial volume effects limit the ability to determine relatively high uptake that appears around the necrotic zone.

Discussion

The present report demonstrates a significant correlation of 18F-EF5 uptake with single-dose radiation response for cells derived from 9L gliosarcoma tumour cells. To our knowledge, this is the first time such a result has been reported in any animal model. Our data have also confirmed a similar ability for EF5 binding as measured by flow cytometric analysis, using the relatively simple parameter ‘mean flow cytometry signal’. With two relatively uncommon exceptions, single-dose radiation-response is not a standard therapeutic method but is considered a clinically relevant estimate of the oxygenation state of the tumour at the time of actual irradiation (Chapman et al. 1983, Moulder & Rockwell 1984). The exceptions for single-dose human therapy are intraoperative radiotherapy and stereotactic radio-surgery. The ability to image sub-tumoural regions of hypoxia (or, for example, hypoxia in primary versus nodal disease) would be relevant to dose painting using image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT). Thus, the data presented herein may allow direct clinical application to several hypoxia-related therapies.

As mentioned in the introduction, several clinical trials have shown that pretreatment tumour hypoxia, as measured by uptake of FMISO, FAZA (1-(5-fluoro-5-deoxy-α-D-arabinofuranosyl)-2-nitroimida-zole) or Cu-ATSM, can be used to differentiate patient outcome using standard therapy (Beck et al. 2007, Dehdashti et al. 2003, Rajendran et al. 2006, Rischin et al. 2006). From this information, it is reasonable to expect that advances in the sensitivity and/or specificity of hypoxia-marker technology would directly translate to its utility in clinical studies.

Beneficial properties of EF5 include its high biological stability, freedom from non-oxygen dependent metabolism, well-characterised biochemical characteristics in preclinical studies, capability of use for immunohistochemical studies (at relatively high drug concentrations) and extremely even biodistribution (due to stability and lipophilicity) (Koch 2002). Although the requirement for electrophillic fluorination using 18F-F2 gas appears limiting for widespread use of EF5, two additional technologies have been developed that allow manufacture of radioactive fluorine gas using standard proton-producing cyclotrons (Bergman & Solin 1997, Nickles et al. 1984). Additionally, electrophillic fluorination is now useful for the production of F-Dopa, which appears to have great value in the clinical decision-making process for therapy of childhood insulinoma (Otonkoski et al. 2006, Ribeiro et al. 2005).

At present, no hypoxia marker has shown perfect sensitivity and specificity in prediction of clinical outcome and indeed it would be unrealistic to expect hypoxia to dominate over all other response modifiers. This applies also to the present animal study. Due to the scatter in the correlative data (relatively low r2 value) it was not possible to order the individual tumour-cell survivals based on EF5 uptake. This suggests that we still do not know whether hypoxia is the dominant modifier of therapeutic response.

A number of prior pre-clinical studies, using other compounds and models, have made various comparisons between markers, or have evaluated the variation in marker uptake under conditions expected to cause acute changes in tumour oxygenation. For example, Lewis and colleagues measured the fraction of EMT6 tumour with positive uptake of Cu-ATSM and found this to be consistent with the known radiobiological hypoxic fraction for this tumour model (Lewis et al. 1999). Using the 9L glioma model, Cu-ATSM uptake was also found to vary with oxygen-modifying treatments such as hydralazine and oxygen breathing (Lewis et al., 2000). In the rat 36B10 glioma model, Rasey and colleagues found a good correspondence between dynamic FMISO uptake and radiobiological hypoxic fraction. However, these parameters did not track each other when the animals were administered low-pO2 gas and the dynamic measurements did not track imaging data (Rasey et al. 2000). Chapman and colleagues compared uptake of IAZGP (1-(6-deoxy-6-iodo-β-D-galactopyranosyl)-2-nitroimidazole) and HL-91 (99mTc-2,2′-(N,N′(1,4-diaminobutane)) bis(2-methyl-3-butanone) dioxime) with pO2 as measured by microelectrodes in anaplastic rat prostate tumours (R3327-AT). They found a good correspondence between the two markers, but neither correlated with pO2, on an individual tumour basis (Iyer et al. 2001). Saitoh and colleagues compared energy metabolism monitored by MRI, pO2 by microelectrodes, IAZGP uptake and surviving fraction at 10 Gy in a murine mammary carcinoma (FM3A), all as a function of tumour size which was varied over a 200-fold range. In this tumour model, all assays including those monitoring hypoxia, showed a highly significant correlation with tumour size. However, comparisons between assays within individual tumours were not made (Saitoh et al. 2002). In 2004, Aboagye and colleagues compared Oxylite® oxygen measurements with FETA ([2-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2-fluor-oethyl)-acetamide) uptake in several different tumour types and found a good correlation between the two measurements (Barthel et al. 2004). In the same year, Gronroos compared FETNIM (1-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-4-fluoro-butane-2,3-diol) and FMISO uptake in murine C3H tumours, finding that both drugs could track increased oxygenation (decreased drug uptake) by carbogen (Gronroos et al. 2004). In an extensive comparison of FMISO uptake versus immunohistochemical staining of CA9 or pimonidazole in a rat rhabdomyosarcoma, DuBois and colleagues found a nearly perfect correspondence between the three markers, even allowing for a broad range of threshold settings for the immunohistochemical stains (Dubois et al. 2004). In contrast O’Donoghue and colleagues, using an anaplastic rat prostate tumour model (R3327-AT), found a very complex, time-dependent relationship between Cu-ATSM and FMISO uptake versus pimonidazole binding (O’Donoghue et al., 2005). Solomon and colleagues used gefitinib therapy (anti VEGF) to modify the oxygenation of A431 xenograft tumours, as monitored by FAZA uptake or pimonidazole binding. In contrast to the results of Saitoh described above, there was no tumour-size dependence of hypoxia as measured by these markers in this tumour model. Gefitinib treatment decreased tumour hypoxia, as assessed by FAZA imaging or drug uptake and also by pimonidazole binding (Solomon et al. 2005). Recently, Yuan and colleagues found correspondence between EF5 binding, assessed using immunohistochemistry, and Cu-ATSM uptake, assessed by autoradiography, in 9L and R3230 but not FSA tumours (Yuan et al. 2006).

The above summary emphasises the variability in tumour models, oxygen modifying techniques and assay methods used to test non-invasive hypoxia markers in animals. Only two of these papers addressed the question of whether the assay techniques correlated with therapeutic response (they did not). Thus, it is not known at present whether the studies reported herein (i.e., successful correlation of radioresponse with EF5 uptake) represent a true advance over prior techniques or rather the use of a different experimental approach. A potential advantage of this tumour model is that it has been previously shown to have a varying tumour-to-tumour radiosensitivity for intermediate passage tumours (Evans et al. 1996).

Initially, we found the lack of significant correlation between the two hypoxia assays (i.e., EF5 binding versus radioactive EF5 uptake; Figure 4) very puzzling, especially considering that both forms of EF5 are chemically identical. Although in principle a PET image should provide the best overall tumour information, it can be limited in spatial resolution and dynamic range due to voxel size and partial volume effects. Additionally, the uniformity of 18F-EF5 distribution cannot be independently assessed or guaranteed at high resolution and there has been substantial discussion in this field regarding the ability of hypoxia markers to detect hypoxia independently of perfusion (Groshar et al. 1993). For the present experiments, whole-tumour response studies (e.g. using growth delay or tumour cure) were not performed. Conversely, the equivalence of tumour samples for the gamma counts versus survival and flow cytometry assays depends upon the initial spatial heterogeneity of the tumour and relies upon the ability of the mincing procedure to compensate for this heterogeneity.

It might be expected that the flow-cytometery versus plating efficiency assays should be the most similar, since they start from an identical cell suspension containing millions of cells per ml. However, with the exception of the most sensitive (oxic) tumour, the total range of surviving fraction after an in vivo dose of 17 Gy encompasses a factor of less than ten (Figures 1–3). We know that the plating efficiency for unirradiated ‘control’ tumours ranges from about 15 to 35% (Evans et al. 1996). Thus, a substantial portion of variation in surviving fraction at 17 Gy is expected to arise from plating efficiency variations and these would not be expected to change with tumour oxygenation.

All EF5-related assays have relied on the average metabolism of EF5 (either binding or uptake) and it is important to note that this prevents consideration of the distribution of hypoxia among the surviving cells. Since each of binding, uptake and radiation survival has a non-linear dependency on pO2 one would expect additional scatter in data expressed as pairwise linear correlations. Additionally, while the cell-yield for disaggregation of the 9L gliosarcoma (up to 50 million cells per gram – data not shown) is high for an in vivo to in vitro assay the total cell number in the initial tumour tissue may be 5 times higher still. Thus, there may be selection processes in the tissue disaggregation process that cause non-equivalent effects on the flow cytometry and plating assays. Similarly, the gamma count assay accounts for all cells of the mince portion used, whereas the disaggregated cells represent only a fraction of their separate total mince portion. Using our current irradiator, there will certainly be some spatial heterogeneity in the radiation dose distribution. This could in some cases interact positively and in others negatively with the intratumoural spatial heterogeneity of hypoxia known to be associated with this model (Jenkins et al. 2000). Finally, we have previously shown that the 9L gliosarcoma contains very high cellular cysteine levels that vary from tumour to tumour (Koch & Evans 1996). High cysteine would tend to push tumour radioresistance towards higher pO2 values while not having much impact on the oxygen dependence of EF5 binding (Horan & Koch 2001). To summarise, it would clearly be of benefit to find tumour models that showed an even greater range of variability in radiation response than does the 9L.

There are several relevant differences between the work reported herein using 18F-EF5 and that of investigations from the literature using other hypoxia imaging agents. As indicated in the introduction EF5 is the most lipophilic 2-nitroimidazle currently undergoing human clinical trials as a hypoxia detecting agent. Hydrophilic compounds can have a very short plasma half-life in mice, allowing the ratio between tissue-bound drug and circulating unbound drug to increase. However, drug half life increases substantially in humans, so that even the most hydrophilic markers under current study have drug half-lives in humans that are much longer than the isotope half-life of 18F (Koch et al. 2001). For this reason, development of EF5 has emphasised the likelihood of very uniform biodistribution with minimal drug elimination over the probable scanning times for human studies (Komar et al. 2008). Indeed, our own unpublished data and that from other investigators (e.g., Dr Barbara Kaser-Hotz, Zurich) indicate an extremely flat background in human and large animal PET images. In our ongoing pharmacology studies comparing EF5 and FMISO in rats, the ratio of counts in blood versus several normal tissues is much closer to unity for EF5 (e.g., see Figure 3b for muscle) than FMISO. Unexpectedly, llittle difference has been seen between the biodistribution patterns for the two markers in brain tissue, where one would expect lipophilicity to be most important (data not shown). This finding is currently under study.

An additional experimental difference between the study reported herein compared to those cited from the literature is that of drug concentration. This variable can greatly impact drug biodistribution, pharmacology and biochemistry but has not previously been studied in the field of non-invasive hypoxia markers (Koch 1990). As explained in the methods section, we purposely used a very low specific activity of 18F-EF5 for the present experiments (i.e., high whole-body drug concentration of ~100 μM) to allow the parallel measurement of EF5 binding via immunohistochemistry. To directly test for the impact of much lower drug concentrations in future experiments would not be compatible with the sensitivity of immunohistochemical detection by flow cytometry. It should be possible to use gamma counts to measure EF5 uptake over a 100-fold reduced concentration (e.g., down to 1 μM) using present techniques, although the amount of radioactivity would then be too low for PET camera imaging. A further concentration reduction of 100 (e.g., down to 10 nM) would be possible using the methods to produce high SA fluorine gas developed by Solin and collaborators (Bergman & Solin 1997).

Conclusion

In summary, the present report demonstrates a highly significant correlation between 18F-EF5 uptake and the radioresistance of cells from individual 9L gliosarcoma tumours. This capability could be caused by inherent properties of this tumour model, advantageous properties of EF5 such as high lipophilicity and biological stability, or the use of relatively high drug concentrations. Our ongoing studies aim to define the relative importance of each of these factors. A survey of the literature suggests that it may be useful to compare different hypoxia markers under otherwise identical experimental conditions.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Grant RO1-CA87645 and the Departments of Radiation Oncology and Radiology at the University of Pennsylvania for financial support, and to The National Cancer Institute for the supply of unlabelled EF5.

Drug and other acronyms

- EF5

[2-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoropropyl)-acetamide]

- FMISO

1-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-3-fluoro-2-propan-2-ol

- FETA

[2-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2-fluoroethyl)-acetamide

- FETNIM

1-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-4-fluoro-butane-2,3-diol

- FAZA

1-(5-fluoro-5-deoxy-α-D-arabinofuranosyl)-2-nitroimidazole

- IAZGP

1-(6-deoxy-6-iodo-β-D-galactopyranosyl)-2-nitroimidazole

- Cu-ATSM

Cu(II)-diacety-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbaxone

- HL-91

99mTc-2,2′-(N,N′(1,4-diaminobutane))bis(2-methyl-3-butanone) dioxime

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: EF5 is patented (inventors include CJK, AVK, WRD) with rights assigned to the University of Pennsylvania. UPENN has a licensing agreement with Varian.

References

- Arbeit JM, Brown JM, Chao KSC, Chapman JD, Eckelman WC, Fyles AW, Giaccia AJ, Hill RP, Koch CJ, Krishna MC, Krohn KA, Lewis JS, Mason RP, Melillo G, Padhani AR, Powis G, Rajendran JG, Reba R, Robinson SP, Semenza GL, Swartz HM, Vaupel P, Yang D. Hypoxia: Importance in tumor biology, noninvasive measurement by imaging, and value of its measurement in the management of cancer therapy. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2006;82:699–757. doi: 10.1080/09553000601002324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger JR. Imaging hypoxia in tumors. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 2001;31:321–329. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.26191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel H, Wilson H, Collingridge DR, Brown G, Osman S, Luthra SK, Brady F, Workman P, Price PM, Aboagye EO. In vivo evaluation of [18F]fluoroetanidazole as a new marker for imaging tumour hypoxia with positron emission tomography. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90:2232–2242. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck R, Roper B, Carlsen JM, Huisman MC, Lebschi JA, Andratschke M, Picchio M, Souvatzoglou M, Machulla H-J, Piert M. Pretreatment 18F-FAZA PET predicts success of hypoxia-directed radiochemotherapy using tirapazamine. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:973–980. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Solin O. Fluorine-18-labeled fluorine gas for synthesis of tracer molecules. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 1997;24:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizel DM, Scully SP, Harrelson JM, Layfield LJ, Bean JM, Prosnitz LR, Dewhirst MW. Tissue oxygenation predicts for the likelihood of distant metastases in human soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Research. 1996;56:941–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao KS, Bosch WR, Mutic S, Lewis JS, Dehdashti F, Mintun MA, Dempsey JF, Perez CA, Purdy JA, Welch MJ. A novel approach to overcome hypoxic tumor resistance: Cu-ATSM-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2001;49:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JD, Franko AJ, Koch CJ. The fraction of hypoxic clonogenic cells in tumor populations. In: Fletcher GH, Nervi C, Withers HR, editors. Biological bases and clinical implications of tumor radioresistance. New York: Masson Publishing; 1983. pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JD, Zanzonico P, Ling CC. On measuring of hypoxia in individual tumors with radiolabeled agents. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42:653–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CN, Halsey J, Cox RS, Hirst K, Blaschke T, Howes AE, Wasserman TH, Urtasun RC, Pajek T, Hancock S, Phillips TL, Noll L. Relationship between the neurotoxicity of the hypoxic cell radiosensitizer SR 2508 and the pharmacokinetic profile. Cancer Research. 1987;47:319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CN, Urtasun RC, Wasserman TH, Hancock S, Harris JW, Halsey J, Hirst VK. Initial report of the Phase I trial of the hypoxic cell radiosensitizer SR-2508. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1984;10:1749–1753. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Mintun MA, Lewis JS, Siegel BA, Welch MJ. Assessing tumor hypoxia in cervical cancer by positron emission tomography with 60Cu-ATSM: Relationship to therapeutic response – a preliminary report. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2003;55:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbier WR, Li A-R, Koch CJ, Shiue C-Y, Kachur AV. [18F]-EF5, a marker for PET detection of hypoxia: Synthesis of precursor and a new fluorination procedure. Journal of Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2001;54:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Landuyt W, Haustermans K, Dupont P, Bormans G, Vermaelen P, Flamen P, Verbeken E, Mortelmans L. Evaluation of hypoxia in an experimental rat tumor model by [18F]fluoromisonidazole PET and immunohistochemistry. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;91:1947–1954. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschmann S-M, Paulsen F, Reimold M, Dittmann H, Welz S, Reischi G, Machulla H-J, Bares R. Prognostic impact of hypoxia imaging with 18F-misonidazole PET in non-small cell lung cancer and head and neck cancer before radiotherapy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Hahn S, Pook DR, Zhang PJ, Jenkins WT, Fraker D, Hsi RA, McKenna WG, Koch CJ. Hypoxia in human intraperitoneal and extremity sarcomas. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2000;49:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Jenkins KW, Jenkins WT, Dilling T, Judy KD, Schrlau A, Judkins A, Hahn SM, Koch CJ. Imaging and analytical methods for the evaluation of vasculature and hypoxia in human brain tumors. Radiation Research. 2008;170:677–690. doi: 10.1667/RR1207.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Koch CJ. Prognostic significance of tumor oxygenation in humans. Cancer Letters. 2003;195:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Jenkins WT, Joiner B, Lord EM, Koch CJ. 2-nitroimidazole (EF5) binding predicts radiation sensitivity in individual 9L subcutaneous tumors. Cancer Research. 1996;56:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn RT, Bowen SR, Bentzen SM, Mackie TR, Jeraj R. Intensity-modulated x-ray (IMXT) versus proton (IMPT) therapy for theragnostic hypoxia-based dose painting. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2008;53:4153–4167. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/15/010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyles AW, Milosevic M, Wong R, Kavanagh MC, Pintilie M, Chapman W, Levin W, Manchul L, Keane TJ, Hill RP. Oxygenation predicts radiation response and survival in patients with cervix cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1998;48:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos T, Bentzen L, Marjamaki P, Murata R, Horsman MR, Keiding S, Eskola O, Haaparanta M, Minn H, Solin O. Comparison of the biodistribution of two hypoxia markers [18F]FETNIM and [18F]FMISO in an experimental mammary carcinoma. European Jornal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2004;31:513–520. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groshar D, McEwan AJ, Parliament MB, Urtasun RC, Golberg LE, Hoskinson M, Mercer JR, Mannan RH, Wiebe LI, Chapman JD. Imaging tumor hypoxia and tumor perfusion. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1993;34:885–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosu A-L, Souvatzoglou M, Roper B, Dobritz M, Wiedenmann N, Jacob V, Hans-Jurgen W, Reischl Gn, Hans-Juergen M, Schwaiger M, Molls M, Piert M. Hypoxia imaging with FAZA-PET and theoretical considerations with regard to dose painting for individualization of radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2007;69:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockel M, Knoop C, Schlenger K, Vordran B, Baussmann E, Mitze M, Knapstein PG, Vaupel P. Intratumor pO2 predicts survival in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1993;26:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan A-M, Koch CJ. The Km for radiosensitization by oxygen is much greater than 3 mm of Hg and is further increased by elevated levels of cysteine. Radiation Research. 2001;156:388–398. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0388:tkmfro]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsman MR, Khalil AA, Nordsmark M, Grau C, Overgaard J. Relationship between radiobiological hypoxia and direct estimates of tumour oxygenation in a mouse tumour model. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1993;28:69–71. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90188-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer RV, Haynes PT, Schneider RF, Movsas B, Chapman JD. Marking hypoxia in rat prostate carcinomas with b-D-[125I] Azomycin galactopyranoside and [99mTc]HL-91: Correlation with microelectrode measurements. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42:337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WT, Evans SM, Koch CJ. Hypoxia and necrosis in rat (L glioma and Morris 7777 hepatoma tumors: Comparative measurements using EF5 binding and Eppendorf needle electrode. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2000;46:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp JS, Surti S, Freifelder R, Daube-Witherspoon ME, Cardi C, Adam LE, Muehllehner G. Performance of a brain PET camera based on Anger-Logic GSO detectors. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;44:1340–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh MC, Tsang V, Chow S, Koch C, Hedley D, Minkin S, Hill RP. A comparison in individual murine tumors of techniques for measuring oxygen levels. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1999;44:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ. Competition between radiation protectors and radiation sensitizers in mammalian cells. In: Nygaard OF, Simic MG, editors. Radioprotectors and anticarcinogens. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 275–296. [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ. The reductive activation of nitroimidazoles; modification by oxygen and other redox-active molecules in cellular systems. In: Adams GE, Breccia A, Fielden EM, Wardman P, editors. Selective activation of drugs by redox processes. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 237–247. NATO Series. [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ. Measurement of absolute oxygen levels in cells and tissues using oxygen sensors and the 2-nitroimidazole EF5. In: Sen CK, Packer L, editors. Methods in enzymology –Antioxidants and redox cycling. Vol. 353. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ. Importance of antibody concentration in the assessment of cellular hypoxia by flow cytometry: EF5 and pimonidazole. Radiation Research. 2008;169:677–688. doi: 10.1667/RR1305.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ, Evans SM. Cysteine concentrations in rodent tumors: unexpectedly high values may cause therapy resistance. International Journal of Cancer. 1996;67:661–667. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960904)67:5<661::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ, Evans SM, Lord EM. Oxygen dependence of cellular uptake of EF5 [2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoroproply)acetamide]: Analysis of drug adducts by fluorescent antibodies vs bound radioactivity. British Jornal of Cancer. 1995;72:869–874. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CJ, Hahn SM, Rockwell KJ, Covey JM, McKenna WK, Evans SM. Pharmacokinetics of the 2-Nitroimidazole EF5 [2-(2-nitro-1-H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoro-propyl)acetamide] in Human Patients: Implications for Hypoxia Measurements In Vivo. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2001;48:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s002800100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W-J, Rasey JS, Evans ML, Grierson JR, Lewellan TK, Graham MM, Krohn KA, Griffin TW. Imaging of hypoxia in human tumors with [F-18]fluoromisonidazole. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1991;22:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)91001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komar G, Seppänen, Eskola O, Lindholm P, Grönroos JT, Forsback S, Sipilä H, Evans SM, Solin O, Minn H. 18F-EF5: A new PET tracer for imaging hypoxia in head and neck cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2008;49:1–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn KA, Link JM, Mason RP. Molecular imaging of hypoxia. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2008;49:129S–148S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Siemann DW, Koch CJ, Lord EM. Direct relationship between radiobiological hypoxia in tumors and monoclonal antibody detection of EF5 cellular adducts. International Journal of Cancer. 1996;67:372–378. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960729)67:3<372::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JS, McCarthy DW, McCarthy TJ, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Evaluation of 64Cu-ATSM in vitro and in vivo in a hypoxic tumor model. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1999;40:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JS, Sharp TL, Laforest R, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Tumor uptake of copper-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicar-bazone): Effect of changes in tissue oxygenation. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2000;42:655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord EM, Harwell LW, Koch CJ. Detection of hypoxic cells by monoclonal antibody recognizing 2-nitroimidazole adducts. Cancer Research. 1993;53:5271–5276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder JE, Rockwell SC. Hypoxic fractions of solid tumors: Experimental techniques, methods of analysis and a survey of existing data. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1984;10:695–712. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickles RJ, Daube ME, Ruth TJ. An 18O2 target for the production of [18F]F2. International Journal Applied Radiation Isotopes. 1984;35:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nordsmark M, Overgaard M, Overgaard J. Pretreatment oxygenation predicts radiation response in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1996;41:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)91811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue JA, Zanzonico P, Pugachev A, Wen B, Smith-Jones P, Cai S, Burnazi E, Finn RD, Burgman P, Ruan S, Lewis JS, Welch MJ, Ling CC, Humm JL. Assessment of regional tumor hypoxia using 18F-fluoromisonidazole and 64Cu(II)-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) positron emission tomography: Comparative study featuring microPET imaging, pO2 probe measurment, autoradiography, and fluorescent microscopy in the R3327-AT and FaDu rat tumor models. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2005;61:1493–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otonkoski T, Nanto-Salonen N, Seppanen M, Veijola R, Huopio H, Hussain K, Tapanainen P, Eskola O, Parkkola R, Ekstrom K, Guiot Y, Rahier J, Laakso M, Rintala R, Nuutila P, Minn H. Noninvasive diagnosis of focal hyperinsulinism of infancy with [18F]-DOPA Positron Emission Tomography. Diabetes. 2006;55:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran JG, Schwartz DL, O’Sullivan J, Peterson LM, Ng P, Scharnhorst J, Grierson JR, Krohn KA. Tumor hypoxia imaging with [F-18] fluoromisonidazole positron emission tomography in head and neck cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12:5435–5441. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasey JS, Casciari JJ, Hofstrand PD, Muzi M, Graham MM, Chin LK. Determining hypoxic fraction in a rat glioma by uptake of radiolabeled fluoromisonidazole. Radiation Research. 2000;153:84–92. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0084:dhfiar]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro M-J, De Lonlay P, Delzescaux T, Boddaert N, Jaubert F, Bourgeois S, Dolle F, Nihoul-Fekete C, Syrota A, Brunelle F. Characterization of hyperinsulinism in infancy assessed with PET and 18F-Fluoro-L-DOPA. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46:560–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rischin D, Hicks RJ, Fisher R, Binns D, Corry J, Porceddu S. Prognostic significance of [18F]-misonidazole positron emission tomography-detected tumor hypoxia in patients with advanced head and neck cancer randomly assigned to chemoradiation with or without tirapazamine: A substudy of trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study 98.02. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:2098–2104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh J-I, Sakuri H, Suzuki Y, Muramatsu H, Ishikawa H, Kitamoto Y, Akimoto T, Hasegawa M, Mitsuhashi N, Nakano T. Correlations between in vivo tumor weight, oxygen pressure, 31P NMR spectroscopy, hypoxic microenvironment marking by b-D-iodinated azomycin galactopyranoside (b-D-IAZGP), and radiation sensitivity. International Journal Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2002;54:903–909. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siim BG, Menke DR, Dorie MJ, Brown JM. Tirapazamine-induced cytotoxicity and DNA damage in trasplanted tumors: relationship to tumor hypoxia. Cancer Research. 1997;57:2922–2928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon B, Binns D, Roselt P, Weibe LI, McArthur GA, Cullinane C, Hicks RJ. Modulation of intratumoral hypoxia by the epidermal growth factor receptor unhibitor gefitinib detected using small animal PET imaging. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2005;4:1417–1422. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick PL, Ernst LA, Tauriello EW, Parker SR, Mujumdar RB, Mujumdar SR, Clever HA, Waggoner AS. Cyanine dye labeling reagents – carboxymethylindocyanine succinimidyl esters. Cytometry. 1990;11:418–430. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surti S, Karp JS, Perkins AE, Cardi CA, Daube-Witherspoon ME, Kuhn A, Muehllehner G. Imaging performance of A-PET: A small animal PET camera. IEEE Transactions Medical Imaging. 2005;24:844–852. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2005.844078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorwarth D, Eschmann S-M, Scheiderbaur J, Paulsen F, Alber M. Kinetic analysis of dynamic 18F-fluoromisonidazole PET correlates with radiation treatment outcome in head-and-neck cancer. BioMed Central Cancer. 2005;5:152–162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorwarth D, Soukup M, Alber M. Dose painting with IMPT, helical tomography and IMXT: A dosimetric comparison. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2008;86:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: Significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2007;26:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallen CA, Michaelson SM, Wheeler KT. Evidence for an unconventional radiosensitivity of rat 9L subcutaneous tumors. Radiation Research. 1980;85:529–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman P. Pharmacokinetics of hypoxic cell radio-sensitizers. Cancer Clinical Trials. 1980;3:237–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Schroeder T, Bowsher JE, Hedlund LW, Wong T, Dewhirst MW. Intertumoral differences in hypoxia selectivity of the PET imaging agent 64Cu(II)-diacetybis(N4-methylthiosemicarbaxone) Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47:989–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemer LS, Evans SM, Kachur AV, Shuman AL, Cardi CA, Jenkins WT, Karp JS, Alavi A, Dolbier WR, Koch CJ. Noninvasive imaging of tumor hypoxia in rats using the 2-nitroimidazole 18F-EF5. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;30:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]