Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the frequency of retained placenta at the University College Hospital Ibadan (UCH). and to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients and examine the risk factors predisposing to retained placenta.

Methods:

This is a descriptive study covering a period of 5 years from January 1st 2002 to December 31st 2006. During the study period, 4980 deliveries took place at the University College Hospital, Ibadan and 106 cases of retained placenta were managed making the incidence 2.13 per cent of all births.

Results:

During the five year period, there were 106 patients with retained placenta; of these, 90 (84.9%) case notes were available for analysis. The mean age was 29.37 ± 4.99 years. First and second Para accounted for 52 per cent of the patients. Majority of the patient were unbooked for antenatal care in UCH with booked patients accounting for 27.8 per cent of the cases. The mean gestational age at delivery was 34.29 ± 6.02. Three patients presented to the hospital in shock of which 2 died on account of severe haemorrhagic shock. Fifty-eight patients (64.8%) presented with anaemia (packed cell volume less than 30 per cent) and 35 patients (38.8%) had blood transfusion ranging between 1-4 pints. 1 patient required hysterectomy on account of morbidly adherent placenta. Eleven patients (12.2%) had placenta retention in the past, 28 patients (31%) had a previous dilatation and curettage, 14 patients (15.5%) had previous caesarean sections and 47 patients (41.3%) had no known predisposing factors

Conclusion:

Retained placenta still remains a potentially life threatening condition in the tropics due to the associated haemorrhage, and other complications related to its removal. The incidence and severity may be decreased by health education, women empowerment and the provision of facilities for essential obstetric services by high skilled health care providers in ensuring a properly conducted delivery with active management of the third stage of labour.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of retained placenta varies greatly around the world, affecting between 0.1 and 3.3% of vaginal deliveries depending on the population studied1. In spite of many developments in the field of obstetrics, retained placenta continues to be responsible for maternal deaths globally as it is associated with a high case fatality rate 2 . Retained placenta is defined as failure of delivery of the placenta 30 minutes after childbirth although some authorities accept a time limit of 60 minutes3. In Europe, manual removal of placentas are advised at anything between 20 minutes and over 1 hour into the third stage.4 The choice of timing is a balance between the post-partum haemorrhage risk of leaving the placenta in situ, the likelihood of spontaneous delivery and the knowledge from caesarean section studies that the manual removal itself causes haemorrhage5. In a study of over 12,000 births, Combs and Laros found that the risk of haemorrhage increased after 30 minutes6. The choice of timing for manual removal depends on the facilities available and the local risks associated with both post-partum haemorrhage (PPH) and manual removal of the placenta (MROP). In the United Kingdom, 30 minutes was suggested by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)7, whereas, the World Health Organization manual for child birth suggests 60 minutes8.

Retained placenta is potentially life-threatening especially in women of low social class who constitute a significant proportion of our population due to preexisting malnutrition, anaemia, home deliveries and lack of facilities. There is considerable variation in the retained placenta rate between countries. In less developed countries, it affects about 0.1% of deliveries while in more developed countries an incidence of 3% has been documented1.

Retained placenta is reported with a frequency of 1.1 – 3.3 per cent of deliveries6. The overall risk of retained placenta in the general population has been estimated to be about 2.1 per cent13. And where this has occurred once before, the risk of repetition is said to be 2 to 4 times the risk of those patients without any such previous history13. However, there is also a regional variation in the risk associated with it, with the case fatality rate being inversely proportional to the incidence1.

Reasons for this difference in prevalence between the least and most developed countries relate to the differences in aetiological factors for a prolonged third stage1. Adelusi et al9 reported an incidence of 0.6 percent in Saudi Arabia while Chhabra and Madhuri14 reported 0.2 per cent in Maharashtra, India.

Of the several complications of the third stage of labour, retained placenta together with the often associated post-partum haemorrhage occupies a unique place11. Retained placenta has been shown to be the second major indication for blood transfusion in the third stage of labour after uterine atony12,13.

Various studies have examined risk factors predisposing to retained placenta. In a series of 13,000 deliveries by Combs and Laros6 logistic regression identified nine factors that were independently associated with a third stage of over 30 minutes. The strongest was with gestational age, but high rates were also found in deliveries in a labour bed (rather than standing or squatting), pre-eclampsia, previous abortions extremes of parity or age, non-Asian race and midwifery deliveries6.

Similarly in a case-control study by Adelusi et al9 in Saudi Arabia, logistic regression analysis showed significant associations of retained placenta with multiparity, induced labour, small placenta, high blood loss, high pregnancy number, previous uterine injury and pre-term labour. These studies suggest that interventions common in the most developed countries (abortions, labour induction,) might be contributing to their high rates of retained placenta. It has also been suggested that uterine abnormalities might be an aetiological factor for retained placenta10, however, given the rarities of these abnormalities in the general population, (0.2%) it would seem unnecessary to investigate every woman with retained placenta for uterine abnormalities.

However, there is no consensus on the role of the various risk factors on the incidence of retained placenta. The frequency of retained placenta with its attendant sequelae of obstetric haemorrhage and infections may be reduced with anticipation of problems and active management of the third stage of labour.

OBJECTIVES

To determine the frequency of retained placenta at the University College Hospital Ibadan.

To describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients and examine the risk factors predisposing to retained placenta.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a descriptive study covering a period of 5 years from January 1st 2002 to December 31st 2006. All patients with retained placenta seen at the University College Hospital, Ibadan were included in the study. The case notes of such patients were retrieved from the Medical Records Department of the hospital and relevant data extracted from them. The derived data were analyzed using the EPI-INFO version 10 programme with results expressed as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

During the study period, 4980 deliveries took place at the University College Hospital, Ibadan and 106 cases of retained placenta were managed making the incidence 2.13 per cent of all births.

Of the 106 patients with retained placenta; 90 (84.9%) case notes were available for analysis. The mean age was 29.37 ± 4.99 years with a range of 19–42 years. Table 1 shows the parity of the patients with first and second para accounting for 52 per cent of the patients with a mean parity of 1.75. 15 patients (17%) had tertiary education while Secondary and Primary education accounted for 40% and 43.3% respectively. Table 2 shows the occupation of the patients with traders constituting 54 per cent of the total study population.

Table 1:

Parity distribution of patients with retained placenta in U.C.H, Ibadan

| PARITY | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 26.67 |

| 1 – 2 | 47 | 52.22 |

| 3 – 4 | 15 | 16.66 |

| ≥5 | 4 | 4.44 |

| Total | 90 | 100 |

Table 2:

Occupation of patients with retained placenta in U.C.H., Ibadan.

| OCCUPATION | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Trader | 49 | 54.44 |

| House Wife | 13 | 14.44 |

| Artisan | 9 | 10.00 |

| Civil Servant | 9 | 10.00 |

| Health Worker | 2 | 2.22 |

| Others | 8 | 8.88 |

| Total | 90 | 100 |

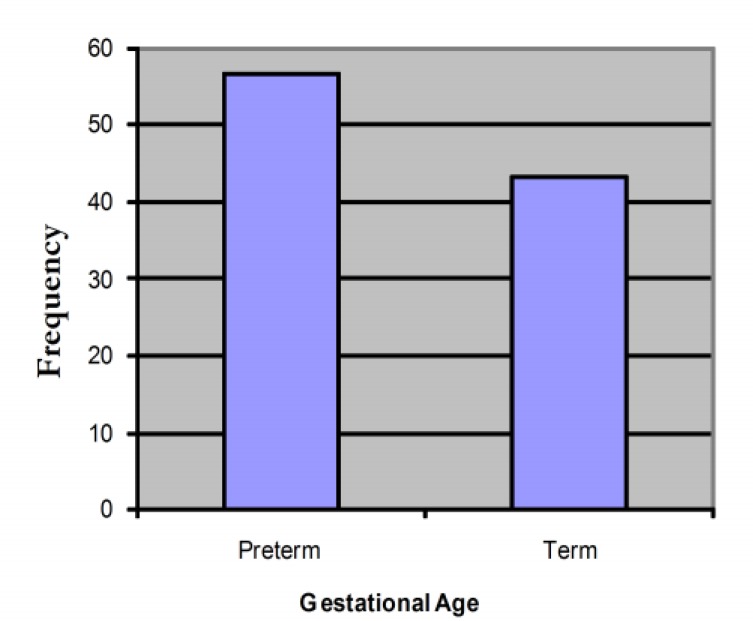

Majority of the patient were unbooked for antenatal care in UCH. Booked patients accounted for 27.8 per cent of the cases. Yoruba’s accounted for 84 per cent of the cases managed. The mean gestational age at delivery was 34.29 ± 6.02. Figure 1 shows that preterm delivery (<37 weeks) occurred in 51 patients accounting for 56.7 per cent of the cases.

Figure 1:

Frequency distribution of gestational age at Delivery of Patients with retained placenta in Ibadan.

Three patients presented to the hospital in shock of which 2 died on account of severe haemorrhagic shock. Fifty-eight patients (64.8%) presented with anaemia (packed cell volume less than 30 per cent) and 35 patients (38.8%) had blood transfusion ranging between 1-4 pints. 1 patient required hysterectomy on account of morbidly adherent placenta. Eighty-two patients had spontaneous vertex deliveries while 8 patients had assisted breech deliveries. Fifty-nine patients had spontaneous onset of labour while 14 had induction of labour and 7 patients had augmentation of labour. The mean duration of admission was 6.66 ± 3.93 days with a range of 2–17 days.

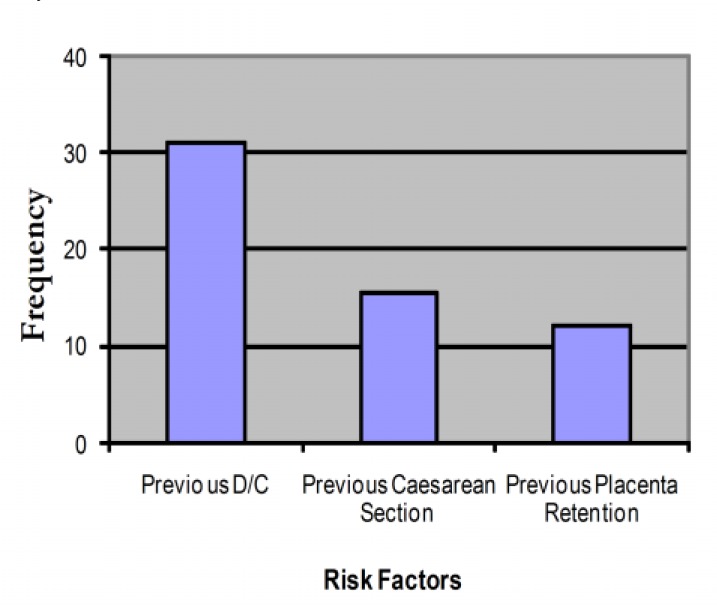

Figure 2 shows that 11 patients (12.2%) had placenta retention in the past, 28 patients (31%) had a previous dilatation and curettage, 14 patients (15.5%) had previous caesarean sections and 47 patients (41.3%) had no known predisposing factors. Overall, 12 patients (13.3%) had partially separated placenta which could be removed with sedation only and in one patient; the placenta had already separated and was removed after starting an intravenous oxytocin infusion.

Figure 2:

Frequency distribution of risk factors in patients with retained placenta in U.C.H., Ibadan.

DISCUSSION

Retained placenta remains a potentially life threatening condition because of the associated haemorrhage and infection that may develop as well as complications related to its removal. A frequency of 1.1–3.3% of deliveries has been reported in literature and this present study found an incidence of 2.13% in Ibadan.

The mean age at presentation was 29.37 ± 4.99 years; majority of the patients being first and second para with a preponderance of Yorubas a reflection of the geographical location of the hospital in the South West. The mean gestational age at delivery was 34.29 ± 6.02 weeks with preterm delivery accounting for 56.7% of the total deliveries. It has been shown that the preterm placenta covers a relatively larger uterine surface than the term placenta and as a result, expulsion of the preterm placenta may require more uterine work and time, predisposing to retention18.

Twenty-eight patients had a previous dilatation and curettage whilst fourteen patients had caesarean sections in the past. These procedures inadvertently cause injury facilitating the infiltration of the uterine muscles by the chorionic villi due to deficient or damaged endometrium at such site. Eleven patients had placenta retention in the past which carries a risk of repeat retention of about 2 to 4 times that of those without history of retained placenta11.

Grand multiparity, a risk factor implicated in retained placenta predisposes to increased abnormalities of placental implantation15. Fibrous tissue reduces the contractile power of the uterus and this may lead to uterine atony and therefore placental retention16. However, in this study, only 4 patients representing 4.4% of the study population were grandmultiparous. 38.8 percent of the study population required transfusion on account of anaemia which often complicates placenta retention. Case fatality has often been attributed to the admission of morbid patients; in this study, two patients died from severe haemorrhagic shock.

A retained placenta requires manual removal and often curettage with the patient under anaesthesia. These procedures increase the risk for maternal complications including uterine perforation, haemorrhage, infection and uterine synechia.17,18 A properly conducted delivery with active management of the third stage of labour can reduce the incidence of retained placenta, and if retention occurs, timely appropriate measures can save life14.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

Retained placenta still remains a potentially life threatening condition in the tropics; due to the associated haemorrhage, infection as well as complications related to its removal. The risk factors for retained placenta include preterm delivery, previous history of placenta retention and uterine surgery.

The incidence and severity may be decreased by provision of infrastructures and improved social amenities, health education and women empowerment coupled with essential obstetric services by highly skilled health care providers in ensuring a properly conducted delivery with active management of the third stage of labour.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew D.W. The Retained Placenta. Best practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;Vol 22(No 6):1103–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO), 1989 - Geneva. The prevention and management of post partum haemorrhage. Report of a Technical Working Group (WHO/MCH/90.7) p. 4.

- 3.Prendiville W.J, Harding J.E , Elbourne D.R, Stirrat G.M. The Bristol third stage trial: active versus physiological management of third stage of labour. British Medical Journal. 1988;297:1295 –1300. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6659.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EUPHRATES Group (European Project on Obstetric Haemorrhage Reduction: Attitude, Trials and Early Warning System). European Consensus on prevention and management of post-partum Haemorrhage. A textbook of PPH. Duncow Sapiens Publishing; 2006. pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hidar S, Jennane T.M , Bouguizane S, et al. The effect of placental Removal method at caesarean delivery on perioperative Haemorrhage: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol . 2004;117(2):179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Combs C.A, Laros R.K . Prolonged third stage of labour: Morbidity and risk factors. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1991;77: 863–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (NCCWCH). Intra-partum care. Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. London: RCOG press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for essential practice.PpB11. 2nd edn. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adelusi B, Soltan M.H, Chowdhury N, Kangave D. Risk of retained placenta: Multivariate approach. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1997;76:414 –418. doi: 10.3109/00016349709047821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green L.K, Harris R.E. Uterine abnormalities. Frequency of Diagnosis and associated obstetric complications. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47:427–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stones R.W, Paterson C.M, Sounders N.J. Risk factor for major obstetrics haemorrhage. Eur. J. Obstet. Reprod. Biol . 1993; 48:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(93)90047-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamani A.A, McMorland G.A , Wadsworth L.D. Utilization of red blood cell transfusion in an obstetric setting. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1988. pp. 1171–1181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hall M.H, Halliwell R, Carr-Hill R. Concomitant and repeated happening of complication of the third stage of labour. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1985;92:732– 738. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.S Chhabra, Madhuri Dhorey. ‘Retained placenta, continues to be fatal but frequency can be reduced’. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;Vol. 22(No. 6):630–633. doi: 10.1080/0144361021000020402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang A, Larkin P, Ester E.J, Condie R, Morrison J. The obstetric performance of grandmultipara. Medical Journal of Australia. 1977;1:330 –332. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1977.tb76717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beazley J.M. Complications of the third stage of labour. In Dewhurst Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for postgraduates. 5th edition. pp. 368–376.

- 17.Castadot R.G. Pregnancy termination: techniques, risk and complications and their management. Fertil. Steril. 1986;45: 5 – 17. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenker J.R, Margalioth E.J. Intrauterine adhesions: an updated appraisal. Fertil. Steril. 1982;37:593–610. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brass P, Misch K.A. Endemic placenta acreta in population of remote villagers in Papua New Guinea. . British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:167– 174. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attal P.H, Shastrakar V. A. Retained placenta (Ten years study) Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 1984;34:83–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weeks A.D, Mirembe F.M. The Retained Placenta - New insight into an old problem. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102:109–110. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Coverden-de-Groot H.A, Howland R.C, Vader C.G. Management of the third stage of labour in a Midwife Obstetric Unit in Cape Town. S. Afr. Med. J. 1982;62:478–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero H, Hsu V.C, Athanassiadis A.P, Hagay Z, Avila C, Norris J, et al. Preterm delivery – a risk factor for retained placenta. Am J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1990;163:823–825. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91076-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas W. Manual removal of the placenta. Am. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1963;86:600–606. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(63)90603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chhabra S, Jeste S . Retained placenta – a review. Indian Medical Journal . 1989; 83:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen W.R. Post-partum uterine haemorrhage. In: Cherry S.H, Merkatz I.R, editors. In: Complications of pregnancy: Medical, Surgical, Gynaecologic, Psychosocial and Perinatal. 4th edn. Ch 72. Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore; 1991. pp. 1132–1141. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obed T.Y, Omigbodun A. Retained placenta in patients with uterine scars. In Nig. Medical Practitioner. 1995;Vol. 30(No ¾):36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirz D.S, Haag M.K. Management of the third stage of labour in pregnancies terminated by prostaglandins E2 . Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989;160:412 –414. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]