Short abstract

Patients and their care givers have created an impressive array of online health resources. Can healthcare professionals tap into them?

In 1994, as a part of an initiative by the department of neurology of the Massachusetts General Hospital to develop promising new ways of using information technology, we began to study how patients with neurological concerns were using online health resources. To our surprise, we found that thousands of patients and their care givers had already created an impressive variety of online health resources. The online support groups, each devoted to a single neurological condition, were especially intriguing.

The opportunities that these electronic groups offered for meeting members' needs were more convenient, powerful, and complex than anything we had seen in face to face support groups. For example, patients attending medical centres around the world could compare the treatments their clinicians had recommended. Participants found it easy to send complex medical information (medical journal articles, research reports, etc) to other patients, complete with links to yet other sources. But the groups we observed were scattered and uncoordinated. And although groups existed for most of the common neurological concerns, patients with uncommon conditions had no way of finding one another.

We decided that our team of e-health researchers might be able to help—by providing better “homes” for existing support groups, and by encouraging the formation of needed groups. So in March 1995 the hospital's neurology service instituted a family of online groups called the Brain Talk Communities (www.braintalk.org) to support e-patients with neurological concerns.

Building from the bottom up

Most medical professionals who have set out to develop online resources for patients have created applications and content in a “top down” manner, directed by health professionals. Within such systems, end users (patients, their care givers, and their family members) usually have little or no input or control. Since the communities we had observed seemed to be doing quite well on their own, we chose a different approach.

Rather than taking on the traditional “provider as authority” role, we decided that we would think of ourselves as architects and building contractors, creating an online system in response to our end users' requests. Our ultimate goal was neither to direct nor to monitor our e-patients' activities. Instead, we set out to give them exactly what they asked for. Thus, rather than specifying the topic areas and designing the underlying information technology structure ourselves, we asked our e-patients what they wanted and designed the system by following their suggestions.

We launched the project by establishing basic discussion groups for epilepsy (DH's primary subspecialty) and 34 other groups specific to conditions or issues ranging from Alzheimer's disease to Tourette's syndrome. These forums were open to the public and were not moderated by the developers. Other than providing the initial topic threads, we stood back and let the users develop and manage the site on their own. Thus from the very beginning, Brain Talk has been a user driven or “bottom up” community space. Patients, not doctors, provide the content and make and administer the rules.

What happens when e-patients take the lead?

Today, braintalk.org hosts more than 250 communities devoted to neurological and related disorders—from agoraphobia, Alzheimer's, and autism to temporo-mandibular joint disorders, tinnitus, and trigeminal neuralgia. Patients also have created birds-of-a-feather groups that deal with related topics—Single Parents with Disabling Conditions and Teens Helping Teens are two examples. In addition, some groups—also initiated by the patients—focus on issues that cut across a variety of medical concerns, like our very popular Artistic Expression and Therapy community where people use creative writing and art to help them deal with neurological concerns, or the Forget-Me-Not Garden of Memories, where participants share stories of loved ones who have died.

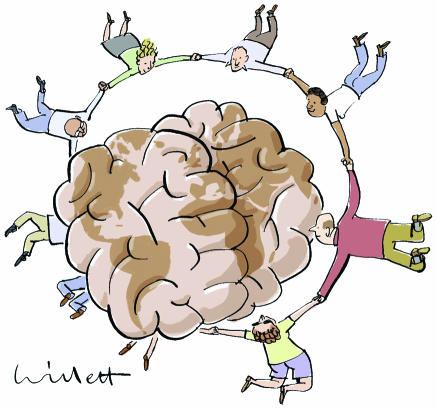

Figure 1.

Highlights from e-patient survey data

For research purposes only, we monitored the postings of the Brain Talk epilepsy support group. Many of the survey data we have collected derive from that population (links to many of our surveys can be found at patientweb.net). Between March 1995 and February 1997, more than a quarter of a million e-patients and family care givers accessed the epilepsy forum to read or contribute.2

Roughly the same proportions of care givers and patients posted messages to the forum

Questions regarding treatment, the clinical course of the illness, the experience of having epilepsy, and side effects of drugs were common

In 20% of the postings, users incidentally mentioned that their clinicians had not met their information needs

A panel of three neurologists and a neurology nurse judged that 6% of the posted information contained factual inaccuracies. In 1998,3 40% of 105 survey respondents said that they used the forum because their clinician did not or could not fulfil their information needs

-

Forum members greatly overestimated the prevalence of inaccurate information in the postings on the forum. Our earlier analysis showed that about 6% of the posted information was inaccurate, yet when polled:

- - 75% of users felt that 10% or more of the information was inaccurate

- - 53% felt that 25% or more of the information was inaccurate

- - 22% felt that 50% or more of the information was inaccurate

But 95% said that the presence of inaccurate information on the forum did not negatively affect their experience. In 2001 we surveyed all Brain Talk participants to collect demographic and descriptive data and ask participants about their online experiences. Some of the demographic data can be found at http://fisher.mgh.harvard.edu/cscw/demo_data.html

The last time they went on line for health purposes, 46% of the 1281 respondents posted some material for someone else to read, and 19% of people had some kind of online interaction with another person

More than two thirds of survey respondents connected with Brain Talk at least once a day and about a third checked in several times a day

57% said that they usually visit more than one forum: 29% visit two, 25% visit three to five forums, and 3% visit six or more

The most frequently visited forums were muscular sclerosis, chronic pain, epilepsy, spinal disorders, depression, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, child neurology, Parkinson's disease, thoracic outlet syndrome, fibromyalgia, workman's compensation, chapel, and general neurology

At their last visit to their healthcare provider, 39% of respondents felt that they had not been given a chance to completely explain the reasons for their visit, and 40% felt that the provider didn't listen completely to what they did have to say; 6% of these said they felt the provider didn't listen at all

72% felt that they had not received a complete explanation of the potential side effects of the drugs their clinicians prescribed

-

53% said that when they came to their clinician's office, they had questions about their care or treatment that they wanted to discuss but did not do so. The most commonly cited reasons for failing to discuss these issues were:

- - Provider didn't have time to listen (47%)

- - Patient forgot to bring up the questions (37%)

- - Patient did not have time to bring them up (29%)

- - Patient was embarrassed about bringing them up (21%)

74% said that they were treated with complete respect and dignity at their last clinician's visit

5% felt that in general their healthcare provider did not treat them with respect and dignity

46% said that they wanted to be more involved in decisions about their care

Our members' resourcefulness and creativity continue to astound us. Several dozen housebound patients with multiple sclerosis who were injecting themselves with the drug Avonex (interferon beta-1a) every week recently organised a chat room called Club Avonex. Most members found the self injection process extremely stressful; even though they lived in many different time zones, the group members all agreed to adjust their injection schedules so that they could all log on to the Club Avonex chat room and inject themselves at the same time. This made it possible for participants to offer each other guidance and support before, during, and after the injection.

Putting it all together: Lester's law

After nearly a decade of e-patient research, we've concluded that what e-patients actually do on line is more complex—and more social—than most health professionals realise. A typical e-patient with multiple sclerosis might say, “First I'm going to check my e-mail—including my mailing list messages—and respond as needed. Then I'll go see if there are any new messages on my three favourite bulletin boards, and maybe post a few comments. Then I'll check my favourite chat room to see who's there, and if I don't get into any interesting discussions, I'll check my MS buddy list to see who's on line right now and see if I can invite some friends to join me there. And after that I'm having lunch with Matt, an MS-er from California, whom I know really well from the group, but whom I've never met before face-to-face. And after lunch I need to go to on line to read the latest issues of the three key medical journals for MS so I can summarise the key articles for my support group.”

Moreover, online community members can also sometimes provide medical advice to those who can't easily access a clinician themselves. As one e-patient recently explained: “When I talk to my doctor, I hear myself asking questions that my online `family' needs to know. It's as if all these other people—the members of my group—are asking questions through me. And whatever answers I hear from my doctor, I know I'll share with them on line.”

Much of what we have learnt in our collaborations with e-patients can be summed up in what has come to be known as Lester's law: “Medical knowledge is a social process: the conversations that occur around artefactual data are always more important than the data themselves.”1

Practical advice for doctors

Health professionals interested in observing e-patient dynamics can learn a good deal from going out into the self help neighbourhoods of cyberspace as observers. Find a few of the most impressive e-patient pioneers within your own areas of interest. Observe them, and if appropriate, communicate with them. See if you can find some low profile way to support their efforts, such as referring your patients to the group, answering group members' questions, or providing small scale sponsorships or grants. But please don't attempt to direct or control their efforts. And don't even think about attempting to put your advertising on their sites.

The things you learn from observing and communicating with the e-patients you find on line may prove invaluable in your future work. This has certainly been true with us.

One of us (DH) is a neurologist specialising in epilepsy. Having learnt about the value and dynamics of online groups through our e-patient research, he now routinely encourages all of his epilepsy patients to participate in a private in-house online support community. He participates in the discussions too, and as his patients get to know one another and become familiar with each group member's unique neurological conditions, he's working with them to develop and explore more sophisticated ways in which he and the group can collaborate. In the next phase of our e-patient research, we hope to explore these new types of online co-care in which e-patients, online support groups, and clinicians can collaborate in unprecedented ways.

Summary points

Patients reach out and connect with others over the internet in a complicated, highly organised social support network

Doctors can find ways to help patient online communities and explore them without being intrusive

The impact and importance that online communities may have on patients should not be underestimated

We are indebted to Tom Ferguson for his many helpful suggestions.

Contributors and sources: Ellie Vogel conceived and co-designed the 2001 Brain Talk survey; SLP and DBH analysed the data. JL, SLP, YF and DBH jointly wrote this paper. DBH is guarantor.

Funding: Some of the work described here was supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine, G03 LM06964.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ferguson T. Medical knowledge as a social process: an interview with John Lester. The Ferguson Report, issue 9, Sep 2002. www.fergusonreport.com/articles/fr00902.htm (accessed 22 Apr 2004).

- 2.Hoch D, Norris D, Marcus AD, Information exchange in an epilepsy forum on the world wide web. Seizure 1999;8: 30-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris D, Lester JE, Hoch DB. An internet forum for epilepsy support: a survey of users. Epilepsia 1998;39(suppl 6): 229. [Google Scholar]