Abstract

Background:

Dental caries is a lifetime disease and its sequelae have been found to constitute health problems of immense proportion in children. Environmental factors such as culture, socioeconomic status, lifestyle and dietary pattern can have a great impact on cariesresistance or caries-development in a child.

Objective:

The present study was conducted to evaluate the relationship between dental caries and socioeconomic status of children attending paediatric dental clinic in UCH Ibadan.

Methods:

Socio-demographic data for each child that attended paediatric dental clinic, UCH Ibadan within a period of one year was obtained and recorded as they presented in the dental clinic, followed by oral examination for each of them in the dental clinic to detect decayed, missing and filled deciduous and permanent teeth (dmft and DMFT respectively).

Results:

The mean dmft and DMFT score for the 209 children seen within period of study were 1.58 ± 2.4 and 0.63+1.3 respectively. Highest caries prevalence (46.9%) was found within the high social class while the caries prevalence in middle and low social class were 40.5% and 12.6% respectively. The highest dmft/DMFT of >7 was recorded in two children belonging to high social class. The difference in dmft in the three social classes was statistically significant (x 2 = 51.86,p= 0.008) but for DMFT, it was not statistically significant (x2 = 6.92, p = 0.991).

Conclusion:

Caries experience was directly related to socio-economic status of the parents of the studied children with highest caries prevalence in high and middle socioeconomic classes.

Keywords: Dental Caries and Socioeconomic status.

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is the most prevalent oral disease and it remains the single most common disease of childhood that is not amenable to short-term pharmacological management1. More than eighty percent of the paediatric population is affected by dental caries by age seventeen1. It’s very high morbidity potential has brought this disease into the main focus of the dental health profession. There is practically no geographic area in the world whose inhabitants do not exhibit some evidence of dental caries. It affects both gender, all races, all socioeconomic status and all age groups2. It does not only cause pain and discomfort, but also in addition, places a financial burden on parents of affected children.

According to WHO’s Global Data for the year 2000 on decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT Index), the level of dental caries in Africa is low relative to the findings in the Americans3. In the 60’s, the prevalence of dental caries in developed countries was found to be generally higher than that in the developing countries with a mean DMFT range of 4.5 – 6.5 in 12 year old in developed countries and 0.1 – 1.1 in the same age group in developing countries4,5 Meanwhile, Petersen3 in his review of various studies on dental caries noticed two distinct trends in the prevalence of the disease. First is the decline in the prevalence of dental caries in developed countries over the past 30 years and second is the increase in the prevalence of the disease in some developing countries. A decrease in mean DMFT as low as 2.6 in some developed countries and an increase in mean DMFT up to 1.7 in some developing countries has been reported3

In some countries in Africa, the prevalence of caries in young children is increasing. In these countries, dental caries is associated with an increase in sugar consumption from food, beverages and sweets, while it remains low in countries where poor economy restricts refined sugar consumption6. Incidence of caries has been on the increase in some rapidly industrializing African communities particularly in the urban communities7.

In Nigeria, studies have shown that dental caries prevalence is on the increase although low compared with findings in developed countries. A mean DMFT of between 1.9 and 2.7 had been reported8-11. Adegbembo et al8, reported in a national survey on dental caries status and treatment need in Nigeria that the proportion of the decayed component of DMFT was 30%, 43% and 45% among subjects aged 12, 15 and 35 - 44 years, respectively. Sofola et. a9. compared the caries prevalence of urban and rural primary school children between 4 and 16 years of age and found the prevalence of 14.4% in urban area and 5.7% in rural children. Furthermore, Okeigbeme10 in a crosssectional survey of school children aged 12-15 years in Egor district of Edo State found a prevalence of 33% among the studied children. Also, a caries prevalence of 11.2% was found in 12-14 year-old school children in Ibadan, Oyo State11.

Studies have also showed that there is relationship between dental caries and socioeconomic status12,13. There studies reported that race, income level, educational level, employment status and other socioeconomic factors have considerable impact on dental caries12,13. Dental caries has been found to be a good proxy to measure socioeconomic development14. In developed countries, higher prevalence of dental caries was found among the children of lower social class and lower prevalence in children of high socio-economic class15. The situation was found to be on the contrary in some developing countries where caries prevalence was found to increase with increasing socio-economic status16,17. However, in Nigeria, a search into the literature shows a dearth of information on the effect and relationship of parental socioeconomic status on dental caries prevalence of the children. Therefore, this study was designed to show the effect of parental socioeconomic status on caries prevalence of children seen at University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan within a one year period.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study in which all paediatric patients less than 16 years that presented for the first time in the Paediatric dental clinic UCH, Ibadan, within a period of 12 months were examined clinically for dental caries. The children with special needs were excluded from the study. Demographic data for each child was obtained and recorded as they present in the clinic. This included the age, sex, social class of parents using the father’s and mother’s occupations, father’s and mother’s level of education. Their socioeconomic status was determined using socioeconomic index score by Oyedeji18 which is as follows:

Parent/Guardian Educational scale

| Scores | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | University graduate or equivalent. |

| 2 | School certificate holder with teaching or other professional training. |

| 3 | School Certificate holder. |

| 4 | Primary six certificate holder. |

| 5 | Illiterate. |

Parent/Guardian Occupational scale

| Scores | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Senior public servants, professionals, business people, large scale traders, contractors. |

| 2 | Intermediate grade public servants, senior school teachers. |

| 3 | Junior grade public servants, junior school teachers, artisans, drivers. |

| 4 | Petty traders, labourers, Messengers |

| 5 | Full time housewives, unemployed, students, subsistence farmers |

The mean of four scores (two for the father/male guardian and two for the mother/female guardian) to the nearest whole number was calculated as the social class assigned to each child.

| Mean Score | Socioeconomic status |

| 1 | High |

| 2 and 3 | Middle |

| 4 and 5 | Low |

For single parent/guardian, the mean score of that single parent/guardian was used.

Clinical examination for dental caries of each child was performed using World Health Organization (1997) criteria for diagnosis of caries. This involved sitting each patient on the dental chair under the illumination attached to the chair. Examination of each child was done using sterile mouth mirror and community periodontal index probe (CPI probes). Each tooth was dried prior to examination and a tooth was said to be “carious” when there was a cavity in its pits, fissure or smooth surface, if there was undermined enamel or a detectable softened floor or wall using the blunt probe. A tooth with chalky white spots in the stagnation areas was also considered carious clinically (Incipient Caries). When a tooth has one or more restoration on it, it was recorded as “filled”. However, a tooth was considered “missing” when it was extracted as a result of caries. However, missing primary teeth due to normal exfoliation were not considered. The dmft (decayed, missing due to caries and filled deciduous teeth) and DMFT (decayed, missing due to caries and filled permanent teeth) for each child was calculated.

Test of statistical analysis was done using chi square test, t test and ANOVA with the SPSS version 11.0. Differences were considered significance at the level of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

During the twelve month study period, a total of 209 children, within the age range of 1-15 years attending the Paediatric dental clinic, UCH, Ibadan for the first time were seen. There were 98 males (47.0%) and 111 females (53.0%). Thirty-nine (18.7%) were within 1-5 years (primary dentition), one hundred and twelve (53.6%) within 6-10 years (mixed dentition) and fifty-eight (27.7%) within 11-15 years (permanent dentition). One hundred and eighteen (56.6%) belong to high social class, 72(34.4%) to middle social class and 19(9.1%) to low social class (Table 1). Only 52.2% of the subjects had dental caries while 47.8% were caries free (Table 1). Frequency distribution of decayed, missing (due to caries) and filled deciduous teeth (dmft) and permanent teeth (DMFT) values among the age groups are presented in Table 2 and 3 respectively. A large number of the children had dmft or DMFTof zero. From Table 2, children aged 6-10 years recorded the highest frequency dmft of 1-3 and six children in the same age group had dmft greater than 7. Mode DMFT of 1-3 was recorded in age group 6-10 and 11-15 years (Table 3). Also a child in the age group 6- 10 had DMFT greater than 7.The difference in caries prevalence in the three age groups was not statistically significant (Table 2 and 3).The mean dmft and DMFT score for the 209 children were 1.58 ± 2.412 and 0.63±1.314 respectively. The mean dmft for males was 1.59 ± 2. 61 while that of females was 1.62 ± 2.25. The difference in mean dmft for males and females was not statistically significant (t = 0.84; P value = 0.56). Also, the mean DMFT for male was 0.39 + 0.88 while that of female was 0.85+ 1.59. This also was not statistically significant (t = 0.67; P value = 0.42). The values of standard deviation are greater than the mean values in this result; this shows the occurrence of outliers in dmft and DMFT values obtained.

Table 1:

Socio-demographic distribution and caries prevalence of the children

| Gender | No (%) |

| Male | 98(47.0) |

| Female | 111(53.0) |

| Age group(years) | |

| 1-5 | 39(18.7) |

| 6-10 | 112(53.6) |

| 11-15 | 8(27.7) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| High | 118(56.6) |

| Middle | 72(34.4) |

| Low | 19(9.0) |

| Caries Prevalence | |

| Caries present | 109(52.2) |

| Caries absent | 100(47.8) |

Table 2:

Frequency distribution of decayed, missing (due to caries) and filled deciduous teeth (dmft) according to the age groups

| Age group (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| dmft | 1-5 | 6-10 | 11-15 |

| 0 | 20 | 58 | 18 |

| 1-3 | 7 | 32 | 4 |

| 4-6 | 8 | 16 | 1 |

| >7 | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| Total | 39 | 112 | 23 |

X2 =20.92, p= 0.402 (Yates correction value = 0.33)

Table 3:

Frequency distribution of decayed, missing (due to caries) and filled permanent teeth (DMFT) according to the age groups

| Age groups(years) | ||

|---|---|---|

| DMFT | 6-10 | 11-15 |

| 0 | 78 | 34 |

| 1-3 | 15 | 19 |

| 4-6 | 3 | 5 |

| >7 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 97 | 58 |

X2= 11.40, p=0.077 (Yates correction value = 0.26)

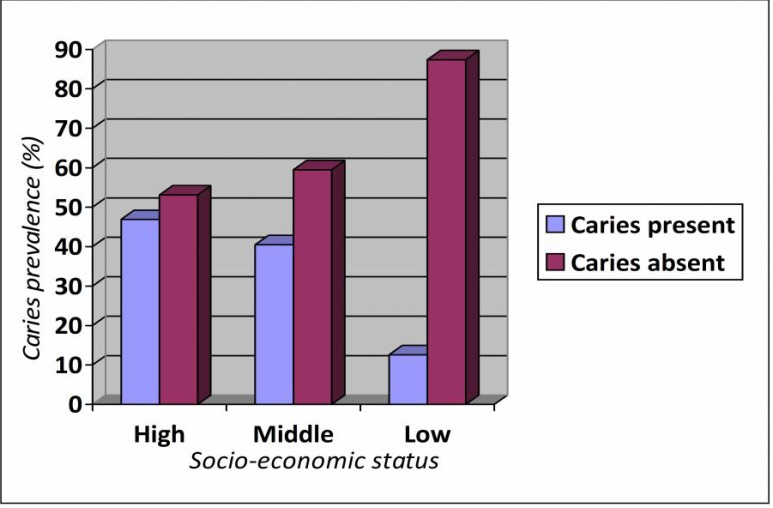

According to Figure 1, the highest caries prevalence (46.9%) was found within the high social class while the caries prevalence in middle and low social class were 40.5% and 12.6% respectively. Tables 5 and 6 also show the frequency distribution of decayed, missing and filled deciduous teeth (dmft) and permanent teeth (DMFT) for the three social classes. Most of the children (irrespective of their social class) had dmft/DMFT of zero. The mode dmft/DMFT Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine. Vol. 11 No. 2 December, 2013 84 in high and middle social classes were found to be 1- 3. The difference in dmft in the three social classes was statistically significant(x2 = 51.86, p= 0.008) while it was not statistically significant for DMFT (x2= 6.92, p = 0.991). Table 7 shows the mean dmft/DMFT for the three social classes, the difference in mean dmft /DMFT of the three social classes were not statistically significant (F=1.84, p= 0.141 and F= 0.25, p= 0.860 respectively).

Figure 1:

Socio-economic status and caries prevalence

Table 5:

Decayed, missing (due to caries) and filled deciduous teeth (dmft) according to the socioeconomic status.

| Socioeconomic status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| dmft | High | Middle | Low |

| 0 | 62 | 24 | 9 |

| 1-3 | 21 | 21 | 1 |

| 4-6 | 9 | 11 | 6 |

| >7 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 99 | 59 | 16 |

X2= 51.86, p= 0.008 (Yates correction value = 0.48)

Table 6:

Decayed, missing (due to caries) and filled permanent teeth (DMFT) according to the socioeconomic status

| Socioeconomic status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DMFT values | High | Middle | Low |

| 0 | 61 | 41 | 10 |

| 1-3 | 20 | 10 | 4 |

| 4-6 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| >7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 86 | 55 | 14 |

X2 6.92, p= 0.991 (Yates correction value = 0.20)

Table 7:

Socioeconomic status of parents and caries prevalence of the children

| Socioeconomic-status | Mean decay, missing and filled deciduous teeth (dmft/SD) | Mean decay, missing and filled permanent teeth (DMFT/SD) |

|---|---|---|

| High | 1.93±2.535 | 0.69±1.425 |

| Middle | 1.40±2.296 | 0.62±1.269 |

| Low | 1.00±1.732 | 0.36±0.674 |

| ANOVA | F= 1.843, p value= 0.141 | F= 0.251, p value= 0.860 |

DISCUSSION

The UCH dental centre is centrally located in Ibadan metropolis and serves all levels of socioeconomic strata without the need for referral in any form. In the present study, it was observed that more than halve of the children seen within the period of study were from high socioeconomic class. This may be due to oral health care awareness among the high socioeconomic class which has resulted in better oral health care service utilization among them.

In the time past, dental caries was considered a disease of the economically developed countries due to their refined carbohydrate consumption but relatively insignificant in the poorer developing countries that depended mainly on natural farm products.20 However, a global reversal in this pattern has been observed.21 Low socio-economic status has been identified as risk factor in dental caries development.14 Other risk factors identified include poor oral hygiene, dietary habits, fluoride exposure, biological factors and medical history.14 There was a higher prevalence of dental caries among children of high and middle social class while a low prevalence was found among children of low social class. This finding is similar to the trend observed in other developing countries16,17,23 where caries prevalence was observed to increase with increasing socio-economic status. Woodward and Walker7 attributed this to an increase in sugar consumption in those developing countries in addition to limited access to fluoride and other dental caries preventive measures. According to Seyedein et al24, developing countries like Kenya, Iraq and Lebanon have westernized their dietary habits which resulted in an increase in their caries prevalence. However, Momeni et al21 reported that Iran recorded a drop in DMFT index from 1.67 in 1993-1994 to 0.77 by 2006 in 12 year-old students, which is very low by WHO standards. This was attributed to increase access to information and dental awareness, which helped those countries to adopt a health conscious lifestyle that is being adopted by their peers worldwide. In developed countries however, an inverse relationship between socio-economic status and caries prevalence was reported, in which high caries prevalence was found in lower socio-economic categories, less affluent areas and some ethnic minorities.15,22

In Nigeria (though a developing country), similar findings to that of developed countries were earlier reported.25,26 The low caries prevalence in high social class was attributed to increase oral health care awareness among the high socioeconomic class and access to dental care by their children at an earlier age. However, the high caries prevalence in middle and low social class was linked to increasing availability and marketing of cheap sugar containing products coupled with low income and poor access to health services and health education in Nigeria. However, the pattern of caries prevalence observed in the present study which is contrary to the earlier studies conducted in Nigeria could be attributed to the fact that this study was carried out in a tertiary dental hospital where larger percentage of attendees were higher social class parents that could afford the cost of dental care and this could also explain the high mean dmft/DMFT observed among the high socioeconomic class. Also, dental caries observed to be low among children from low socioeconomic class could be due to poor oral care seeking behaviour of this group of parents.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study has revealed a direct relationship between socioeconomic status of parents and caries prevalence in children. This shows that it was only an assumption that high and middle socioeconomic class are well informed on oral health care. Therefore, Dental professionals need to focus more on primary prevention of dental caries through public awareness on oral health promotion and education.

Table 4:

Caries prevalence of the children according to gender

| Gender | Mean decay, missing and filled deciduous teeth (dmft/SD) | Mean decay, missing and filled permanent teeth (DMFT/SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.59± 2.61 | 0.39± 0.88 |

| Female | 1.62± 2.25 | 0.85± 1.59 |

| t test | t= 0.84, p value= 0.56 | t= 0.67, p value= 0.42 |

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute of Dental Research. Oral health of the United States children:1986-1987. National Institutes of Health. 1989. pp. 2247–2269.

- 2.Prakash H, Sidhu SS, Sundaram KR. Prevalence of Dental Caries among delhi school chidren. J Ind Dent Assoc. 1999;70:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report. Improvement of oral health in Africa in the 21st century – the role of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Afric J Oral Health. 2004;1:2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sardo-Inferri J, Barmes DE. Epidemiology of oral disease: Differences in national problems. Int Dent J. 1979;29:180–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/FDI. Global goal for oral health in the year 2000. Int Dent J. 1982;23:74–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holm AK. Caries in the pre-school children: International trends. J Dent. 1990;18:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(90)90125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodward M, Walker A.R. Sugar consumption and dental caries evidence from 90 countries. Br Dent J. 1994;176:297–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adegbembo AO, el-Nadeef MA, Adeyinka A. National survey of dental caries status and treatment need in Nigeria. Int Dent J. 1995;45:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sofola OO, Jeboda SO, Shaba OP. Dental Caries Status of primary school children aged 4–16 years in South Western Nigeria. Odontostomatal Trop. 2004;27(108 ):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okeigbeme SA. The prevalence of dental caries among 12–15 year-old school children in Nigeria: Report of a local survey and campaign. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2(1 ):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denloye OO, Ajayi D, Bankole O. A study of dental caries prevalence in 12-14 year old school children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Paediatr Dent J. 2005;15(2 ):147–151. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reisine S, Litt M. Social and psychological theories and their use for dental practice. Int Dent J. 1993;43:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amstutz RD, Rozier RG. Community risk indicators for dental caries in school children: an ecologic study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalloo R, Myburgh NG, Hobdell MH. Dental Caries, socioeconomic development and national oral health policies. Int Dent J. 1999;49:196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1999.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reisine ST, Psoter W. Socioecnomic status and selected behavioural determinants as risk factors for dental caries. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(10 ):1009–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addo-Yobo C, Williams SA, Curzon MEJ. Dental caries experience in Ghana among 12 year old urban and rural school children. Caries Res. 1991;25:311–314. doi: 10.1159/000261382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Normak S. Social indicators of dental caries among Sierra Leonean school children. Scand J Dent Research. 1993;101:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1993.tb01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyedeji G.A. Socioeconomic and Cultural Background of Hospitalized Children in Ilesha. Nig. Paediat. J. 1985;12:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation. Oral Health surveys. Basic methods. 5th 1997. Geneva.

- 20.Per Axelsson. An Introduction to Risk Prediction & Preventive Dentistry. The Axelsson series on preventive dentistry. 1999;1:65–109. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momeni A, Mardi M, Pieper K. Caries Prevalence and Treatment Needs of 12-Year-Old Children in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:24–8. doi: 10.1159/000089381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truin GJ, Konig KG, Bronkhorst EM. Time trends in caries experience of 6- and 12 year-old children of different socioeconomic status in the Hague. Caries Res. 1998;32:1–4. doi: 10.1159/000016422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleaton-Jones P, Chosack A, Haregraves A, Fatti LP. Dental caries and social factors in 12 year old South African children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seyedein M, Zali MR, Golpaigani MV, et al. Oral health survey in 12-year-old children in the Islamic Republic of Iran (1993–1994) Eastern Mediterranean Health J. 1998;4(2 ):338–342. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olajugba OO, Lennon MA. Sugar consumption in 5 and 12 year old school children in Ondo State. Comm Dent Health. 1990;7:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Igbinadolor UP, Ufomata DPE. Dental caries in urban area of Nigeria. Nig Dent J. 2000;12:24–27. [Google Scholar]