Abstract

Purpose of review

Head and neck lymphedema (HNL) is a common and often debilitating cancer treatment effect that is under-researched and ill defined. We examined current literature and reviewed historical treatment approaches. We propose a model for evaluation and treatment of HNL used at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC).

Recent findings

Despite the morbidity associated with HNL in patients with HNC, to our knowledge, no article has been published within the past 18 months whose primary focus is HNL. Eight publications included HNL but only as a secondary focus related to treatment effect, risk of dysphagia, prognostic indicator of underlying disease, and quality of life. A potential benefit of Selenium treatment to reduce HNL was reported.

Summary

This article highlights the recent literature regarding HNL in patients treated for HNC. Although HNL is reported as a potential complication of HNC treatment, no clear definition of the disease or its management are published. Our early experience using an objective evaluation and treatment protocol holds promise for a better understanding of HNL in patients treated for head and neck malignancy.

Keywords: cancer, head and neck, lymphedema

Introduction

Lymphedema, swelling caused by impaired tissue drainage as a result of lymphatic dysfunction, has long been recognized as a potentially serious complication of treatment for patients with breast, gynecologic, or genitourinary cancers [1]. Similarly, the lymphedematous arm or leg, swollen genitalia, or truncal edema are common presentations that are routinely encountered and treated by physicians and certified lymphedema therapists. Although lymphedema is also a significant complication of treatment for head and neck cancer (HNC), its presence in this population is generally under recognized and in most cases, under treated. Thus, head and neck lymphedema (HNL) has received much less attention than lymphedema that affects the extremities. This is likely because of several factors. First, HNC makes up only 3–5% of all cancers compared with the incidence of breast, gynecologic, or genitourinary cancers diagnosed each year [2]. Additionally, less than 50% of patients treated for HNC develop HNL [3]. Finally, most patients with complex tumors of the head and neck are treated in large tertiary centers, thus few clinicians routinely encounter HNL [4]. As a result, there is a paucity of literature and data that clearly describe the presentation, evaluation, and management of HNL in patients with HNC.

Lymphedema results when the lymphatic load exceeds the transport capacity of the lymphatic system because of either vascular malformation (primary lymphedema) or acquired damage to the lymphatics (secondary lymphedema) [1]. Thus, inadequate drainage results in an overload of high protein lymphatic fluid within the interstitial tissues. Chronic lymphostasis results in tissue inflammation that increases fibroblast and connective tissue proliferation. As tissue fibrosis increases, functional impairment can worsen. Secondary lymphedema is a common complication of cancer treatment and can be present in the extremities, trunk, genitalia, or head and neck region [1].

Head and neck cancer and lymphedema

Clinically, the presentation of lymphedema parallels its level of severity. In the earliest stage, HNL may present as “heaviness” or “tightness” without visible edema. As HNL progresses, it is apparent as a barely noticeable fullness without functional detriment, and can progress to pitting edema that may or may not affect function. Although rare in HNC patients, lymphedema can present as grossly disfiguring elephantiasis with severe disability in its final stage.

Similar to other side effects that are associated with the treatment for head and neck tumors, quality of life is often significantly impacted by HNL. The effects of HNL are not simply cosmetic. Significant lymphedema of the face, mouth, and neck can result in substantial functional consequences to communication (speaking, reading, writing, and hearing), alimentation, and respiration [5]. Severe head and neck lymphedema may impede ambulation when vision is impaired. In extreme cases, respiratory obstruction may require tracheotomy [6]. Laryngectomized patients may experience difficulty with stomal access for hygienic purposes, respiration, and management of a tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis. Intra-oral edema and pharyngeal edema can impede swallowing safety and efficiency [7–9], and may mandate a gastrostomy tube for feeding. The psychological effects of facial disfiguration can be grave, including frustration, embarrassment, and depression due to both functional and cosmetic changes [5,10]. The treatment of HNL is essential for the rehabilitation of these deficits and improvement of the patient’s quality of life [10,11]. However, little has been published regarding effective management of HNL.

In addition to speech and swallowing deficits, patients who have been treated for HNC often suffer from reduced cervical range of motion and dysfunction of the arm and shoulder. This further limits the ability to maintain activities of daily living, a common complaint of treated HNC patients [12,13], particularly patients with HNL.

Given the current state of cancer treatment, patients are living longer, either with their disease or disease-free. In either case, the functional sequelae are often severe and may progress as the effects of cancer treatments worsen over time. Additonally, long-term cancer survivors are at risk for cancer recurrence and further treatments that can exacerbate or facilitate the occurrence of HNL. Often, the most severe cases of facial edema present in patients who are at the end of life. The cumulative effects of previous cancer treatments along with a lack of new curative options result in tumor progression that frequently intensifies the edema. Thus the treatment of HNL becomes particularly critical to maximize the patient’s quality of life even if only for a short period of time.

Treatment

Historically, manual lymph drainage (MLD) is credited to Danish massage therapist Emil Vodder, Ph.D., who developed the techniques for treatment of chronic sinusitis in the 1930’s [14,15]. MLD is a series of gentle, circular massage strokes that are applied to the skin to promote increased lymphatic flow. Vodder’s techniques were later used to treat a variety of ailments, including lymphedema, and were first published in 1965 [16]. Twenty-seven years later, Foldi and Foldi [17] combined MLD with compression bandaging, simple physical exercise, and skin care to create Complete Decongestive Therapy (CDT), which is widely accepted today as the “gold standard” for the treatment of lymphedema.

Traditional CDT is typically provided by a certified lymphedema therapist in two phases; first an intensive phase of outpatient treatment is provided 3–5 days weekly over a period of 2–4 weeks. Subsequently, the maintenance phase begins as treatment transitions from the outpatient setting to the home environment. The basic components of the program continue to be emphasized; however, the performance of the program becomes the responsibility of the patient or caregiver [18]. Daily adherence to a home treatment program may be required for the remainder of the patient’s life depending on the severity of the edema.

The basic goals of CDT are to decongest the edematous region, prevent refilling of the tissues, and promote improved drainage. MLD relieves the edema, and exercises combined with compression bandaging enhance the movement of lymph to adjacent areas with intact drainage.

Review of current literature

A literature review was performed through Pubmed. Initial search terms included “lymphedema” or “edema” combined with one or more of the following: “head and neck”, “head”, “neck”, “face”, “ear”, “tongue”, “eyelid”, and “lips”. A total of 429 articles were identified, dating back to 1936. For the purpose of this formal review, articles that discussed primary HNL or HNL resulting from diagnoses other than cancer were excluded. Additionally, articles published before June 2008 were also excluded to maintain a focus on recent publications and adhere to journal aims. Our review also excluded any article that was not published in English; however, two English abstracts from foreign publications were included. Therefore, six articles and two abstracts published between June 2008 and December 2009 met criteria. None of the publications we reviewed provided any discussion regarding the management of HNL using CDT. We therefore added three key articles that were published prior to June 2008 because of their contribution to current methodologies of CDT management of HNL. We have therefore reviewed these articles in addition to the eight publications that met inclusion criteria.

Treatment of HNL with daily dosages of selenium, selen, and sandostatin was reported in two publications [19,20]. These treatments were reported to reduce post-radiation edema of the face and neck, as well as endolaryngeal edema in patients with HNC.

Two publications reported HNL as a late toxicity associated with combined regimens of Cisplatin and radiation treatment [21,22]. However, the significance of Cisplatin as a risk factor for HNL remains unknown.

Three articles, 2 focusing on issues related to end of life and 1 that described dysphagia after radiotherapy, briefly list HNL as a potential contributor to reduced quality of life and dysphagia. Although the recommendation to reduce edema was made, no recommendations regarding intervention were provided [8,9,23].

Finally, an interesting article by Chen, et al. [24] reported a retrospective chart review of 264 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Thirty-two patients (12.1%) were identified with facial edema lasting more than 100 days. The authors did not distinguish between lymphedema or general edema in their patient population. No evaluation or treatment strategies were mentioned, but the authors suggested that the presence of long-standing edema was indicative of underlying disease. Analysis of patient records indicated histories of jugular vein thrombosis, absence of lymph nodes, tumor related vascular compression, and free flaps as the source of the edema.

Three articles published prior to the 18-month review period address the use of CDT techniques in the head and neck region. Piso et al. [7] demonstrated the reduction of postoperative edema after head and neck surgery using Vodder’s method of MLD and custom compression garments to decongest the trunk, neck, and face, by redirecting lymph to the axillary lymph node beds. The value of MLD in reducing facial edema was again reported in 2006 [25] after pedicle flap reconstruction of the face and in 2007 [26] in patients who experienced edema after dental extractions. The focus of intervention was intensive outpatient treatment without carry-over of MLD to the home setting. The use of CDT in the head and neck region has also been documented in European journals that did not meet inclusion criteria for this review [27–29].

M. D. Anderson Cancer Center head and neck lymphedema program

The HNL program at MDACC combines formal evaluation and treatment techniques that are specifically tailored to meet the needs of the presenting patient. A certified lymphedema therapist with specialty training in HNL provides comprehensive evaluation and treatment of patients who are referred for management.

Evaluation

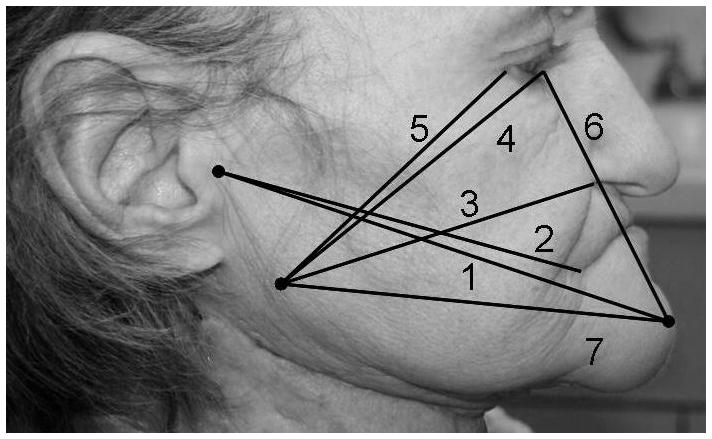

The MDACC HNL evaluation protocol includes patient interview, visual and tactile assessment of the face, neck, and shoulder region, and functional assessments of communication and swallowing. Examination also combines photography, tape measurement, and staging of edema to characterize the overall appearance and severity of the lymphedema. The standard evaluation protocol includes 9 point-to-point tape measurements of the face and 2 facial circumference measurements. Seven key facial measurements are totaled to provide a “composite facial score.” Figure 1 shows the composite facial measures.

Figure 1.

Numbers correspond to composite facial measurements shown in Table 1

-

Facial Circumference

Diagonal: chin to crown of head

Submental: < 1 cm in front of ear, vertical tape alignment

-

Point to Point

Mandibular angle to mandibular angle

Tragus to tragus

-

Facial Composite

Tragus to mental protuberance

Tragus to mouth angle

Mandibular angle to nasal wing

Mandibular angle to internal eye corner

Mandibular angle to external eye corner

Mental protuberance to internal eye corner

Mandibular angle to mental protuberance

Additionally, standard evaluation provides a ‘composite neck score’ that combines the measurements of three neck circumferences. Inferior, medial, and superior neck circumferences are totaled to create a ‘composite neck score’ show below. The individual neck measurements that generate the ‘composite neck score’ are illustrated photographically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Left to right: Composite neck measurements shown in Table 2

Neck circumferences

Superior neck: immediately beneath mandible

Medial neck: midway between point 1 and 3

Inferior neck: lowest circumferential level

Additional facial measurements are obtained when severe edema of the lips or eyes is present. Accurate measurements are critical for baseline comparison and documentation of improvement.

Lymphedema Staging

In addition to documentation using photography and tape measurement, we characterize the severity and presentation of the HNL based on the traditional Foldi rating scale [1] for extremity edema. Unlike the Foldi scale, the MDACC HNL rating scale captures subtle presentations of edema in patients with HNC. Table 1 delineates the MDACC HNL classification scale.

Table 1.

MDACC head and neck lymphedema rating scale

| Levels | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No visible edema but pt reports heaviness |

| 1a | Soft visible edema; no pitting, reversible |

| 1b | Soft pitting edema; reversible |

| 2 | Firm pitting edema; not reversible; no tissue changes |

| 3 | Irreversible; tissue changes |

Note: Adapted from the Foldi Lymphedema Rating Scale [1]

MDACC Scale splits Foldi Level 1 into 1a and 1b to reflect the presence of soft non-pitting edema in patients with HNL.

Treatment

The treatment model used in the Department of Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center is based on experience with over 175 new cases, on average, of HNL per year. The program combines a brief outpatient treatment phase with an aggressive home-based treatment regimen performed by the patient or caregiver. Unlike traditional CDT, we promote the daily use of a home program from the onset of treatment. Patients or caregivers who are judged capable of performing a home therapy program are taught to perform basic self-MLD techniques during 1–2 training sessions. This program is especially suited for patients who cannot participate in prolonged periods of outpatient treatment because of financial, geographic, or transportation restrictions. Despite these limitations, patients with HNL need and have been shown to benefit from self-administered treatment in the home setting when they have been properly trained.

MLD techniques are modified so that patients can easily perform them independently. Decongestive therapy begins in the supraclavicular region and progresses to the trunk, neck, and face. Movement of lymph through anterior or posterior drainage pathways will depend on patterns and extent of scarring. Anterior pathways are generally more usable in patients who have been treated with radiation alone. Patients who have been treated surgically may direct lymph either anteriorly or posteriorly, again depending on the site of resection and subsequent scarring. Techniques that facilitate posterior lymph drainage often require assistance from a second person to help decongest the back. Although modifications to the technique are often possible such that a lack of caregiver assistance does not prohibit the use of posterior drainage pathways, it is important to consider the availability of caregiver support if posterior drainage pathways are required.

Patients with mild to moderate HNL generally benefit from either outpatient treatment or a home program as the primary intervention. However, in severe cases of HNL, intensive outpatient treatment combined with a home therapy program is generally most effective.

The use of compression garments or wrapping is a key component of CDT that traditionally is applied after MLD using a flat, even application of pressure to promote continued lymphatic drainage. Once pitting edema is observed, we modify the timing and the type of compression to promote further softening of the tissue prior to performing MLD. The MDACC technique, unlike traditional CDT, applies compression before and after the MLD, combining the use of irregular and flat compression devices to improve skin elasticity and pliability so that MLD is effective and drainage is enhanced. Standard and custom facial garments are selected to provide further compression as required based on the patient presentation. Cervical and facial range of motion exercises are performed during the compression phase to further facilitate drainage.

Outcomes

Our experience at MDACC with more than 270 patients referred for evaluation and treatment of HNL after HNC treatment [5] suggests that surgically-treated patients may experience worse lymphedema than those treated on organ preservation protocols. Furthermore, patients who receive CDT through intensive outpatient settings as well as those who perform self-administered CDT at home benefit from lymphedema therapy that specifically targets the head and neck. Patients who are compliant with recommended treatment regimens have significantly better rates of improvement than patients who are noncompliant with therapy. Optimal results are likely achieved with programs that combine traditional methods of intensive outpatient CDT followed by a home maintenance program.

Conclusion

As the treatment for cancers of the head and neck become more intense, posttreatment toxicities, including lymphedema, will likely become more severe and provide greater challenges for patients and clinicians to manage. There is a growing awareness of the effect of HNL on the patient’s ability to return to an optimal quality of life. Unfortunately, HNL has not been well studied or documented. We provide an evidenced-based model for the evaluation and treatment of patients with HNL whose foundation rests on the traditional methods of CDT. Future investigations should establish epidemiologic data and a clear definition of HNL in HNC patients. In addition, prospective studies should be designed to verify efficacy and provide management guidelines.

Footnotes

We have no conflict of interest to disclose in relationship to this article. Brad G. Smith is a paid instructor for the Norton School of Lymphatic Therapy.

References

- 1.Foldi M, Foldi E. Lymphostatic diseases. In: Strossenruther RH, Kubic S, editors. Foldi’s textbook of lymphology for physicians and lymphedema therapists. 2. Munich, Germany: Urban and Fischer; 2006. pp. 224–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [accessed December19, 2009]. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/, based on November 2008 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Büntzel J, Glatzel M, Mücke R, et al. Influence of amifostine on late radiation-toxicity in head and neck cancer--a follow-up study. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1953–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubicek GJ, Wang F, Reddy E, et al. Importance of treatment institution in head and neck cancer radiotherapy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewin JS, Hutcheson KA, Smith BG, et al. Early experience with head and neck lymphedema after treatment for head and neck cancer. Poster presentation. Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Symposium; Chandler, AZ. February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Withey S, Pracy P, Vaz F, Rhys-Evans P. Sensory deprivation as a consequence of severe head and neck lymphoedema. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:62–64. doi: 10.1258/0022215011906830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Piso DU, Eckardt A, Liebermann A, et al. Early rehabilitation of head-neck edema after curative surgery for orofacial tumors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:261–269. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200104000-00006. Early evidence for the reduction of postoperative edema after head and neck surgery using MLD and custom compression garments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Murphy BA, Gilbert J. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiation: assessment, sequelae, and rehabilitation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.09.007. This article suggests the potential impact of HNL on swallowing function and quality of life after radiation treatment to the head and neck. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9•.Poulsen MG, Riddle B, Keller J, Porceddu SV, et al. Predictors of acute grade 4 swallowing toxicity in patients with stages III and IV squamous carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radiotherapy alone. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.03.010. This article suggests the potential effect of HNL on swallowing function and quality of life after radiation treatment to the head and neck. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penner JL. Psychosocial care of patients with head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tschiesner U, Linseisen E, Baumann S, et al. Assessment of functioning in patients with head and neck cancer according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF): a multicenter study. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:915–923. doi: 10.1002/lary.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nowak P, Parzuchowski J, Jacobs JR. Effects of combined modality therapy of head and neck carcinoma on shoulder and head mobility. J Surg Oncol. 1989;41:143–147. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930410303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Wilgen CP, Dijkstra PU, van der Laan BF, et al. Morbidity of the neck after head and neck cancer therapy. Head Neck. 2004;26:785–791. doi: 10.1002/hed.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasseroller RG. The Vodder School: The Vodder method. Cancer. 1998;15 (Suppl 12B):2840–2842. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12b+<2840::aid-cncr37>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chikly BJ. Manual techniques addressing the lymphatic system: origins and development. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105:457–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vodder E. Vodder’s lymph drainage. A new type of chirotherapy for esthetic prophylactic and curative purposes. Asthet Med (Berl) 1965;14:190–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foldi M, Foldi E. Practical instructions for therapists-manual lymph drainage according to Dr. E. Vodder. In: Strossenruther RH, Kubic S, editors. Foldi’s textbook of lymphology; for physicians and lymphedema therapists. 2. Munich, Germany: Urban and Fischer; 2006. pp. 526–546. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foldi M, Foldi E. Guidelines for the application of MLD/CDT for primary and secondary lymphedema and other selected pathologies. In: Strossenruther RH, Kubic S, editors. Foldi’s textbook of lymphology; for physicians and lymphedema therapists. 2. Munich, Germany: Urban and Fischer; 2006. pp. 677–683. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micke O, Schomburg L, Buentzel J, et al. Selenium in oncology: from chemistry to clinics. Molecules. 2009;14:3975–3988. doi: 10.3390/molecules14103975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammerl B, Döller W. Secondary malignant lymphedema in head and neck tumors. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s10354-008-0629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tribius S, Kronemann S, Kilic Y, et al. Radiochemotherapy including cisplatin alone versus cisplatin + 5-fluorouracil for locally advanced unresectable stage IV squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Strahlenther Onkol. 2009;185:675–681. doi: 10.1007/s00066-009-1992-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff HA, Overbeck T, Roedel RM, et al. Toxicity of daily low dose cisplatin in radiochemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:961–967. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0532-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honnor A. Understanding the management of lymphoedema for patients with advanced disease. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15:162–166. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.4.41961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Chen MH, Chang PM, Chen PM, et al. Prolonged facial edema is an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Support Care Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0754-8. Epub Oct 12. This retrospective review article establishes facial edema as a long-standing consequence of head and neck cancer. The authors provide several possible etiologies including jugular vein thromboses, absence of lymph nodes, tumor-related vascular compression, and free flap reconstruction. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Szolnoky G, Mohos G, Dobozy A, Kemény L. Manual lymph drainage reduces trapdoor effect in subcutaneous island pedicle flaps. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1468–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.03165.x. This article describes the trapdoor effect, a bulging elevation of tissues within the boundaries of a semicircular or circular scar common to subcutaneous pedicle flaps, and the usefulness of MLD in reducing lymph drainage, thereby improving the cosmetic deformity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Szolnoky G, Szendi-Horváth K, Seres L, et al. Manual lymph drainage efficiently reduces postoperative facial swelling and discomfort after removal of impacted third molars. Lymphology. 2007;40:138–142. This article describes facial swelling associated with dental surgery. Authors use MLD to relieve edema and cosmetic impairment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Einfeldt H, Henkel M, Schmidt-Auffurth T, Lange G. Therapeutic and palliative lymph drainage in therapy of edema in the face and neck. HNO. 34:365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preisler VK, Hagen R, Hoppe F. Indications and risks of manual lymph drainage in head-neck tumors. Laryngorhinootologie. 1998;77:207–212. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rüger K. Lymphedema of the head in clinical practice. Z Lymphol. 1993;17:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]