The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin, which plays a principal role in regulating feeding behavior and energy expenditure, modulates central dopamine systems at multiple levels (1-3). In ob/ob mice, which have a genetic mutation that renders them leptin-deficient, leptin administration was shown to increase dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in the nucleus accumbens by 21% and in the caudate putamen by 29% (2). We now show that in congenitally leptin-deficient humans with an analogous mutation, resumption of leptin treatment, after long-term replacement and short-term removal, does not significantly increase striatal D2/D3 receptor availability.

Three leptin-deficient patients (32-yr-old male A, 39- and 44-yr-old females B and C, respectively) from a family in Turkey and 16 age- and sex-matched healthy control subjects (6 men, 10 women: mean age = 35.3, SD = 8.7) were tested. Patients have a rare, recessive, missense mutation in the ob gene. They had been treated daily with recombinant methionyl human leptin replacement (r-metHuLeptin; Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., San Diego, CA) for six years at the time of this study. As described previously, the treatment substantially normalized eating behavior, weight, and endocrine function, reversibly increased cerebral gray matter concentration, and altered the brain response to food-related cues (4-9).

D2/D3 dopamine receptors were imaged in brain using positron emission tomography (PET), after injection of [18F]fallypride (≤ 5.5 mCi, S.A. ≥ 1 Ci/μmol), a radiotracer with high affinity for these receptors. Each participant underwent two [18F]fallypride scanning sessions. The first session was conducted after daily leptin supplementation had been discontinued for 30 - 32 days (“off-leptin” condition). The second session was conducted 12 - 15 days after supplementation resumed (“on-leptin” condition). Control group sessions were separated by 21 - 75 days, without leptin administration.

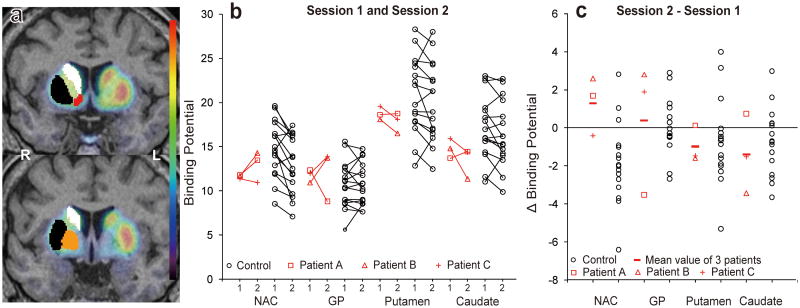

The PET procedure and definition of volumes of interest (VOIs) were described previously (10). D2/D3 receptor binding was estimated in the nucleus accumbens (NAC), globus pallidus (GP), putamen, and caudate nucleus. VOIs were placed using the “FIRST” subcortical segmentation routines within the FSL software distribution (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/first/index.html) (Figure 1a). Binding potential (BPnd), which represents D2/D3 receptor availability, was determined as described previously (10) using the simplified reference tissue model with the cerebellum, which is relatively devoid of D2/D3 receptors, as a reference region.

Figure 1.

Binding potential (BPnd) changes across sessions in leptin-deficient patients and healthy control subjects. (a) Colored volumes-of-interest delineate the caudate nucleus (white), putamen (black), NAC (red) and GP (orange) within the right hemisphere of two coronal sections where a representative PET image is superimposed on the corresponding magnetic resonance image. (b) BPnd values of all participants in the first and second PET sessions; for the three patients (data shown in red), the first and second sessions were conducted under “off-leptin” and “on-leptin” conditions, respectively. (c) Changes in BPnd values obtained by subtracting the BPnd value in session 1 from the BPnd value in session 2. NAC= nucleus accumbens; GP= globus pallidus; L = left hemisphere; R=right hemisphere.

We computed differences scores (session 2 – 1) from BPnd values, and tested the hypothesis that D2/D3 receptor availability did not increase in patients from the first (off-leptin) to the second (on-leptin) scan (Figure 1b and 1c). Z scores were calculated using the corresponding standard deviation from control subjects, averaged, and converted to one-tailed P values. The Z scores of the mean change score for patients were 0.81, 0.47, -0.75 and -1.33, respectively, in NAC, GP, putamen, and caudate. All P values were non-significant (>0.2). Therefore, the null hypothesis (no increase) was accepted for all regions. We set 95% upper limits of 32%, 10%, 7% and 2% for the percentage BPnd increase in the four regions. Figures 1b and 1c suggest, however, that changes in D2/D3 receptor availability in the patients ranged from an increase after leptin replacement in the most ventral VOI (NAC) to a decrease in the most dorsal (caudate).

Using [3H]spiperone in an autoradiographic study, Pfaffly et al. observed that striatal basal D2/D3 receptor availability did not differ between ob/ob and wild-type mice, but that leptin treatment for 8 days increased striatal D2/D3 receptor availability in ob/ob mice, but decreased availability in wild-type mice (2). In a small sample of leptin-deficient humans, we observed no difference in BPnds in comparison with a control group, and no significant increase from the “off-leptin” to “on-leptin” conditions.

Although brief leptin treatment decreased the weight of previously untreated ob/ob mice, they still weighed almost twice as much as wild-type mice (2). In contrast, long-term leptin replacement had substantially normalized body weight and other endocrine functions of our patients (9). Leptin replacement may have also normalized their central dopamine systems in ways which persisted during the one-month leptin-off period. Determination of whether D2/D3 receptor availability and other dopamine system parameters are abnormal prior to the initiation of leptin replacement to individuals with this mutation awaits identification of new cases.

Acknowledgments

Support for the work: US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants P20DA022539 and R01DA020726 (to EDL); K24RR016996, R01DK058851, and U01GM061394 (to JL); K24RR017365 and R01DK063240 (to M-LW); and the UCLA General Clinical Research Center (NIH Grant M01RR00865 to GS Levy). GP-F, M-LW, and JL were supported by The Australian National University institutional funds.

References

- 1.Opland DM, Leinninger GM, Myers MG., Jr Brain Res. 2010;1350:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfaffly J, Michaelides M, Wang GJ, Pessin JE, Volkow ND, Thanos PK. Synapse. 2010;64(7):503–510. doi: 10.1002/syn.20755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Perez SM, Zhang W, Lodge DJ, Lu XY. Mol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.36. e-pub ahead of print 12 April 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Licinio J, Caglayan S, Ozata M, Yildiz BO, de Miranda PB, O'Kirwan F, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(13):4531–4536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308767101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matochik JA, London ED, Yildiz BO, Ozata M, Caglayan S, DePaoli AM, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):2851–2854. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baicy K, London ED, Monterosso J, Wong ML, Delibasi T, Sharma A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(46):18276–18279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706481104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.London ED, Berman SM, Chakrapani S, Delibasi T, Monterosso J, Erol HK, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011. 2011 May 25; doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0314. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman SM, Paz-Filho G, Wong ML, Kohno M, Licinio J, London ED. (submitted for publication).

- 9.Paz-Filho G, Wong ML, Licinio J. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee B, London ED, Poldrack RA, Farahi J, Nacca A, Monterosso JR, et al. J Neurosci. 2009;29(47):14734–14740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3765-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]