Abstract

During the early stage of the avian influenza A(H7N9) epidemic in China in March 2013, a strain of the virus was identified in a 4-year-old boy with mild influenza symptoms. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that this strain, which has similarity to avian subtype H9N2 viruses, may represent a precursor of more-evolved H7N9 subtypes co-circulating among humans.

Keywords: avian influenza virus, viruses, A(H7N9), phylogenetics, evolution, adaption, genome sequence, pediatric, zoonoses, respiratory infections, fomite, China

Influenza A(H7N9) virus infected >400 persons in China during March 2013–April 2014 (1–3) in China. Although this virus does not appear to be readily transmitted from person to person, its identification in a wide geographic area of China and discovery of amino acid changes associated with mammalian adaption of the virus have caused increased concerns for a pandemic (1,2).

The origin and evolution of the H7N9 subtype have been discussed intensively based on the results of phylogenetic analysis of the available sequences (1,4–8). The hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes of the H7N9 subtype that circulated among humans during 2013 were possibly introduced from wild birds that carried differing subtype H9N2 strains and then reassorted in domestic birds such as chickens (4–6). A/brambling/Beijing/16/2012(H9N2) (BJ16)–like virus and/or other related avian virus H9N2 strains are proposed to be the sources of the internal genes of the 2013 H7N9 subtypes (5,7). However, the precise source and evolution route of strains in human H7N9 subtypes have not been well established (4–6). Intermediate or precursor strains are extrapolated to exist at the interface between avian and human H7N9 subtypes (5,6), but such strains have not been identified.

Here we report the identification of a distinct strain, A/Shanghai/JS01/2013(H7N9) (SH/JS01), which was detected in a patient with mild influenza symptoms in Shanghai during March 2013, during the very early stage of the influenza A(H7N9) epidemic. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that this strain may represent an earlier precursor of the more evolved H7N9 subtypes co-circulating at low levels at the time of isolation in March 2013 thus providing insight into the evolution of H7N9 subtypes.

The Study

A mild case of influenza A(H7N9) virus infection was identified in a 4-year-old boy in a rural area of Jinshan District, Shanghai, reported on March 31. The patient had been exposed to poultry. His signs and symptoms included acute fever (maximum 39° axillary), cough, nasal drainage, and tonsillitis. A diagnosis of upper respiratory tract infection was made, and the child recovered after 5 days of antiviral drug therapy (9,10). Nasal swab specimens were positive for influenza A(H7N9) virus by using real-time RT-PCR (11), as recommended by the World Health Organization. Although his family members, unrelated workers, and chickens he may have had contact with were tested, none tested positive for influenza virus.

The whole genome sequence of the SH/JS01strain was amplified from the nasal swab specimen by using RT-PCR (primer sequences available upon request). Strict controls were used during PCR amplification; results were confirmed by another laboratory to exclude contamination with laboratory strains. We constructed maximum likelihood trees of each gene segment sequence using the general time-reversible model implemented in MEGA 5.1 (12), and estimated divergence time using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo method implemented in BEAST (v1.6.1) (13). We compared all known strains of the 2013 H7N9 subtype and other referenced influenza virus sequences deposited in GISAID (http://platform.gisaid.org/epi3/frontend#57f951) and GenBank (Table 1 and Technical Appendix Figures 1–8).

Table 1. The GenBank accession numbers, gene clade, and estimated divergent time of the sequences for A/Shanghai/JS01/2013*.

| Gene segment | GenBank accession no. | Gene clade† | Estimated time of divergence‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | KF609508 | Minor | Jul 2010 |

| PB1 | KF609509 | Major | Jun 2002 |

| PA | KF609510 | Minor | Mar 2012 |

| HA | KF609511 | ND | Oct 2005 |

| NP | KF609512 | Major | Jan 2001 |

| NA | KF609513 | ND | Sep 2010 |

| M | KF609514 | Minor | May 2011 |

| NS | KF609515 | ND | Oct 1996 |

*PB, polymerase basic subunit; PA, RNA polymerase acidic subunit; HA, hemagglutinin; NP, nucleoprotein; NA, neuraminidase; M, matrix gene; NS, nonstructural gene. †Defined according to reference (5); ND, not divided: HA, NA, and NS genes were not divided into clades. ‡Calculations based on sequences in Technical Appendix

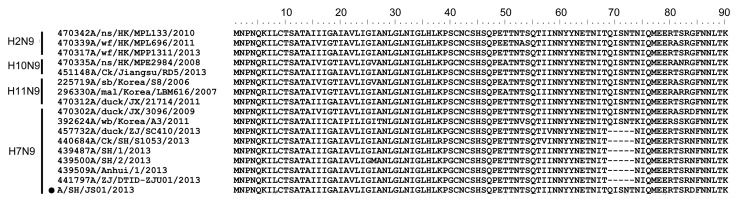

The critical mutations in the SH/JS01 strain associated with virulence and mammalian adaption were compared to 3 prevalent H7N9 subtype reference strains: A/Shanghai/1/2013 (SH/1), A/Shanghai/2/2013 (SH/2), and A/Anhui/1/2013 (AH/1). In the HA gene of SH/JS01, the only mammalian adapting substitution observed was 138A (H3 numbering); amino acid residues involved in receptor-binding specificity showed avian-like signatures, including 186G and 226Q, which were similar to SH/1 but distinctive from SH/2 and AH/1. In the internal genes of SH/JS01, we observed some human-like and mammalian-adapting signatures, including 89V in polymerase basic subunit (PB)2, 368V in PB1, 356R in the RNA polymerase acidic subunit, 42S in nonstructural gene 1, and 30D and 215A in matrix gene 1; however, some hallmark changes involved in mammalian adaptation still showed avian signatures, including 627E and 701D in PB2 and 100V and 409S in the RNA polymerase acidic subunit (Table 2). Most strikingly, SH/JS01 retained aa 69–73 (N9 numbering) in the stalk region of the NA gene. In contrast, deletion of aa 69–73, which is considered to occur when viruses adapt to terrestrial birds, prevailed in all the known 2013 H7N9 subtype isolates (14) (Table 2, and Figure). These findings indicate that SH/JS01 is genetically distinct from all the known human influenza A(H7N9) strains and carries more avian influenza-like signatures.

Table 2. Analysis on critical mammalian-adapting amino acid substitutions in H7N9 virus strains.*†.

| Gene |

Site |

SH/JS01 |

SH/1 |

SH/2 |

AH/1 |

Known mutations |

Relationship to mammalian adaption |

| HA | 138 | A | S | A | A | S138A | Mammalian host adaption |

| 186 | G | G | V | V | G186V | Unknown | |

| 226 | Q | Q | L | L | Q226L | Unknown | |

| 228 | G | G | G | G | G228S | Unknown | |

| NA | 292 | R | K | R | R | R292K | Osteltamivir and zanamivir resistance |

| 69–73 deletion | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Deletion of 69–73 Increased virulence in mice | |

| PB2 | 63 | I | I | I | I | I63T | Co-mediate with PB1 677M, to reduce pathogenicity of H5N1 viruses |

| 89 | V | V | V | V | L89V | Enhanced polymerase activity and increased virulence in mice | |

| 471 | T | T | T | T | T471M | Viral replication, virulence, and pathogenicity | |

| 591 | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q591K | Adapt in mammals that compensates for the lack of PB2–627K | |

| 627 | E | K | K | K | E627K | Enhanced polymerase activity and increased virulence in mice | |

| 701 | D | D | D | D | D701N | Enhanced transmission in guinea pigs | |

| PB1 | 99 | H | H | H | H | H99Y | Results in transmissible of H5 virus among ferrets |

| 353 | K | K | K | K | K353R | Determine viral replication, virulence, and pathogenicity | |

| 368 | V | I | V | V | I368V | Results in transmissible of H5 virus among ferrets | |

| 566 | T | T | T | T | T566A | Determine viral replication, virulence, and pathogenicity | |

| 677 | T | T | T | T | T677M | Co-mediate with PB2 I63T to reduce pathogenicity of H5N1 viruses | |

| PA | 100 | V | A | A | A | V100A | Related to human adaption |

| 356 | R | R | R | R | 356R | Related to human adaption | |

| 409 | S | N | N | N | S409N | Enhances transmission in mammals | |

| M1 | 30 | D | D | D | D | N30D | Increased virulence in mice |

| 215 | A | A | A | A | T215A | Increased virulence in mice | |

| M2 | 31 | N | N | N | N | S31N | Reduced susceptibility to amantadine and rimantadine |

| NS1 | 42 | S | S | S | S | P42S | Increased virulence in mice |

*HA, hemagglutinin; NA, neuraminidase; SH/JS01, A/Shanghai/JS01/2013(H7N9); SH/1, A/Shanghai/1/2013 (H7N9); SH/2, A/Shanghai/2/2013 (H7N9); AH/1, A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9); PB, RNA polymerase basic subunit; PA, RNA polymerase acidic subunit; M, matrix gene; NS, nonstructural gene. †Boldface text indicates the mutant amino acids sites related to mammalian host adaption and increased virulence.

Figure.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the neuraminidase (NA) stalk region. The dark circle indicates the sequence characterized in this study. The abbreviations of the sequence names are as follows: ns, northern shoveler; wf, wild waterfowl; Ck, Chicken; Sb, shorebird; mal, mallard; wb, wild bird; HK, Hong Kong; JX, Jiangxi; ZJ, Zhejiang; SH, Shanghai.

Phylogenetic analysis and divergence time estimation showed that the SH/JS01 HA gene diverged in October 2005 and was closely related to SH/1; nucleotide similarity was 99.7% (online Technical Appendix Figure 1). However, the NA gene, which is most closely related to A/northern shoveler/Hong Kong/MPL133/2010(H2N9) and A/duck/Jiangxi/21714/2011(H11N9) with nucleotide similarity of 99% and 99.3%, respectively, are estimated to have diverged in September 2010, earlier than that of known strains of the 2013 H7N9 subtype (estimated to have occurred in January 2011) (Table 1; Technical Appendix Figure 2).

On the basis of internal genes, 2013 H7N9 viruses have been divided into minor (m) and major (M) clades in the phylogenetic trees, and first 9, then 27 genotypes (5,6,8). Our data showed that SH/JS01 belongs to the m-PB2|PA|M or G3 genotype (Table 1; Technical Appendix Figures 3–8); its NS gene and that of A/Chicken/Dawang/1/2011(H9N2) (DW1), shared the highest nt identity (99.4%). The SH/JS01 NS gene had an estimated divergence time as early as October 1996 (Table 1; Technical Appendix Figure 3). The closest relatives of the SH/JS01 M gene were poultry H9N2 strains A/chicken/Jiangsu/CZ1/2012 and A/chicken/Jiangsu/NTTZ/2013 (nt identity 99.7%); BJ16 (98.6%) was not closely related. The divergence time of SH/JS01 M gene is estimated as May 2011, which is earlier than most 2013 H7N9 isolates (Table 1; Technical Appendix Figure 4). The PB2 and PA genes of SH/JS01 were positioned in minor clades and showed higher identities to A/chicken/Jiangsu/MYJMF/2012(H9N2) (99.2% and 99.3%, respectively) than to BJ16 (97.1% and 98%) (Table 1; Technical Appendix Figures 5, 6). In contrast, the PB1 and NP genes of SH/JS01 belong to the major lineage (Technical Appendix Figures 7, 8). Collectively, these data indicate that, except for PB1 and NP, the internal genes of SH/JS01 are more closely related to those in poultry H9N2 viruses identified before 2013 than to BJ16, which was an H9N2 virus considered to be the donor of most of internal genes of the 2013 H7N9 virus.

Conclusions

SH/JS01, a distinct H7N9 virus strain identified in 2013 during the early stage of the influenza A(H7N9) epidemic in China, provided information to define the evolution of the H7N9 subtype. Although identified in an infected human, SH/JS01 has more avian-prone properties and fewer mammalian-adapting mutations than other known human 2013 H7N9 subtypes. SH/JS01 has a waterfowl-like NA gene characterized by the absence of a deletion in the NA stalk and most of its internal genes are more closely related to avian H9N2 subtype strains isolated during the 2011–2012 influenza season than to other recently emerged strains of the H7N9 subtype. Molecular clock analysis further predicted an earlier divergence time in most genes of SH/JS01. These findings indicate that SH/JS01 might be a precursor strain of the H7N9 virus that co-circulated with more evolved viruses, although we cannot exclude that SH/JS01 may have been generated independently from the other H7N9 strains by reassortment of waterfowl strains with avian H9N2 strains and then transmitted directly to a human.

The sequences of SH/JS01 contained more avian-like signatures than those of other H7N9 isolates from humans; this underscores the potential of these viruses to infect humans. The phenotypic characteristics of SH/JS01, which might describe its zoonotic potential, remain to be investigated.

It is unclear whether other SH/JS01–like viruses are still circulating in poultry in China and if so, what the potential is for their evolution and ability to infect humans. Intensive influenza surveillance and additional influenza A virus genome sequences isolated from poultry and from humans with severe and mild manifestations of infection are needed to clarify the population dynamics of H7N9 viruses.

Phylogenetic analysis of avian influenza viruses, 1988–2013

Acknowledgments

We thank Adolfo García-Sastre for his helpful discussions and critical-reading of this manuscript.

This study was supported in part by grants from Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (KJYJ-2013-01-01-01), National Major Science and Technology Project for Control and Prevention of Major Infectious Diseases of China (2012ZX10004-206), Shanghai Health and Family Planning Commission (12GWZX081, 2013QLG007, 2013QLG001, 2013QLG003), National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (81225014), Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT13007), and Foundation Merieux.

Biography

Dr. Ren is an associate professor at the Institute of Pathogen Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing. Her research is focused on the etiology and pathogenesis of respiratory viruses.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ren L, Yu X, Zhao B, Wu F, Jin Q, Zhang X, et al. Infection with possible avian influenza A(H7N9) virus precursor in a child, China, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Aug [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2008.140325

These authors contributed equally to this work.

These authors contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship.

References

- 1.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1888–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uyeki TM, Cox NJ. Global concerns regarding novel influenza A (H7N9) virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1862–4. 10.1056/NEJMp1304661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Avian influenza A(H7N9) virus [cited 2014 Apr 8]. http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/en/

- 4.Liu D, Shi W, Shi Y, Wang D, Xiao H, Li W, et al. Origin and diversity of novel avian influenza A H7N9 viruses causing human infection: phylogenetic, structural, and coalescent analyses. Lancet. 2013;381:1926–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60938-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu A, Su C, Wang D, Peng Y, Liu M, Hua S, et al. Sequential reassortments underlie diverse influenza H7N9 genotypes in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:446–52. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam TT, Wang J, Shen Y, Zhou B, Duan L, Cheung CL, et al. The genesis and source of the H7N9 influenza viruses causing human infections in China. Nature. 2013;502:241–4. 10.1038/nature12515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, Mao H, Xu C, Jiang J, Chen Y, Yan J, et al. Origin and characteristics of internal genes affect infectivity of the novel avian-origin influenza A(H7N9) virus. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81136. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui L, Liu D, Shi W, Pan J, Qi X, Li X, et al. Dynamic reassortments and genetic heterogeneity of the human-infecting influenza A (H7N9) virus. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3142–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ip DK, Liao Q, Wu P, Gao Z, Cao B, Feng L, et al. Detection of mild to moderate influenza A/H7N9 infection by China's national sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness: case series. BMJ. 2013;346:f3693. 10.1136/bmj.f3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu X, Zhang X, He Y, Wu HY, Gao X, Pan QC, et al. Mild infection of a novel H7N9 avian influenza virus in children in Shanghai. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.World Health Organization. Real-time RT-PCR protocol for the detection of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus [cited 2013 Apr 15]. http://www.who.int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/ cnic_realtime_rt_pcr_protocol_a_h7n9.pdf.

- 12.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung CL, Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Fan XH, Zhang JX, Bahl J, et al. Establishment of influenza A virus (H6N1) in minor poultry species in southern China. J Virol. 2007;81:10402–12. 10.1128/JVI.01157-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic analysis of avian influenza viruses, 1988–2013