Abstract

We investigated the infection rate for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) among ticks collected from humans during May–October 2013 in South Korea. Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks have been considered the SFTSV vector. However, we detected the virus in H. longicornis, Amblyomma testudinarium, and Ixodes nipponensis ticks, indicating additional potential SFTSV vectors.

Keywords: severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, SFTSV, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, SFTS, Phlebovirus, Bunyaviridae, humans, South Korea, viruses, vector, ticks, tickborne, tick-borne, Haemaphysalis longicornis, Amblyomma testudinarium, Ixodes nipponensis, Rhipicephalus microplus

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging disease characterized by fever and thrombocytopenia. The syndrome is caused by SFTS virus (SFTSV), a member of the family Bunyaviridae, genus Phlebovirus (1). SFTSV is related to, but distinctly different from, Heartland viruses, which were isolated in the United States (2).

The first case of SFTS was reported in China during 2010 (1), and in 2013, SFTSV infections were reported in South Korea and Japan (3–5). In South Korea, the first human case of SFTS was confirmed in May, 2013 (3). Although person-to-person transmission of SFTSV through contact with the blood or mucus of an infected person has been reported (6,7), the virus is primarily transmitted to humans by the bite of SFTSV-infected ticks. The virus has been detected in Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann (bush tick) and Rhipicephalus microplus Canestrini (southern cattle tick) ticks (1,8).

H. longicornis ticks comprise the major population of ticks in the environment and have been considered the main vector for SFTSV (9,10). SFTSV has been detected in H. longicornis ticks collected from the environment by using the dragging or sweeping methods and from mammals. However, to our knowledge, the prevalence of SFTSV in ticks collected from humans has not been reported. To increase our understanding of SFTSV and its possible vectors, we determined the prevalence of SFTSV infection among various ticks collected from humans nationwide in South Korea during May–October 2013.

The Study

We collected a total of 261 ticks (113 nymphal, 7 adult male, and 141 adult female ticks) from humans during May–October 2013. The ticks were placed in plastic tubes and transported to our laboratory for identification to species and developmental stage (11); we used a dissecting microscope for identification purposes. Tick samples were homogenized in 600 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), penicillin (500 IU/mL, GIBCO BRL) and streptomycin (500 μg/mL, GIBCO BRL) by using the Precellys 24 tissue homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, Bretonneux, France) and 2.8-mm stainless steel beads. We used a viral RNA extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, South Korea) to extract RNA from the supernatant of the tick homogenates. To detect SFTSV RNA, we performed a 1-step reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) using a DiaStar 2× OneStep RT-PCR Pre-Mix Kit (SolGent, Daejeon, South Korea) with designed primers, MF3 (5′-GATGAGATGGTCCATGCTGATTCT-3′) and MR2 (5′-CTCATGGGGTGGAATGTCCTCAC-3′), under the following conditions: an initial step of 30 min at 50°C for reverse transcription and 15 min at 95°C for denaturation, followed by 35 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 40 s at 58°C, and 30 s at 72°C, and a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C.

Of the 261 identified ticks, 4 nymphal ticks and 18 adult ticks had fed just before collection. The most abundant tick was H. longicornis (81.2%, 212/261), followed by Amblyomma testudinarium Koch (6.5%, 17/261); Ixodes nipponensis Kitaoka and Saito (5.7%, 15/261); H. flava Neumann (5.4%, 14/261); and H. japonica Nutt and Warburton, Ix. persulcatus Schulze, and Ix. granulatus Supino (0.4% each, 1/261) (Table).

Table. Ticks collected from humans in South Korea during a study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, 2013*.

| Tick species, developmental stage | No. ticks | No. pools | No. SFTSV-positive pools | MIR, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemaphysalis longicornis | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 85 | 34 | 1 | 1.2 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 122 | 109 | 11 | 9.0 |

| Subtotal |

212 |

148 |

12 |

5.7 |

| Haemaphysalis flava | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal |

14 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

| Haemaphysalis japonica | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Amblyomma testudinarium | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 16 | 13 | 4 | 25.0 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal |

17 |

14 |

4 |

23.5 |

| Ixodes nipponensis | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 3 | 3 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal |

15 |

15 |

2 |

13.3 |

| Ixodes persulcatus | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs, sex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adults | ||||

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Ixodes granulatus | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Total | ||||

| Larvae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 113 | 54 | 7 | 6.2 |

| Adults, sex | ||||

| M | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 141 | 128 | 11 | 7.8 |

| Total | 261 | 189 | 18 | 6.9 |

*Pools of nymphal and adult ticks contained 1–30 ticks/pool and 1–5 ticks/pool, respectively. MIR, SFTSV minimum infection rate per 100 ticks (no. positive pools/total no. ticks assayed); SFTSV, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus.

We divided the 261 ticks into 189 pools to detect the medium (M) segment gene of SFTSV by RT-PCR: 18 SFTSV-positive pools were detected. The SFTSV minimum infection rate per 100 ticks (MIR) was 5.7% in H. longicornis (12 pools), 23.5% in A. testudinarium (4 pools), and 13.3% in Ix. nipponensis (2 pools) ticks. In fed ticks, the MIR was 18.2% (4 pools), and in unfed ticks, the MIR was 5.9% (14 pools). The mean prevalence of SFTSV in the ticks in the study was 6.9%.

We identified the sequences for the SFTSV-positive tick pools by using the TA cloning method and a TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Because of a cloning failure, the sequence of 1 positive tick pool was not determined. The sequences obtained from 17 SFTSV-positive tick pools were submitted to GenBank (accession nos. KF781489–513).

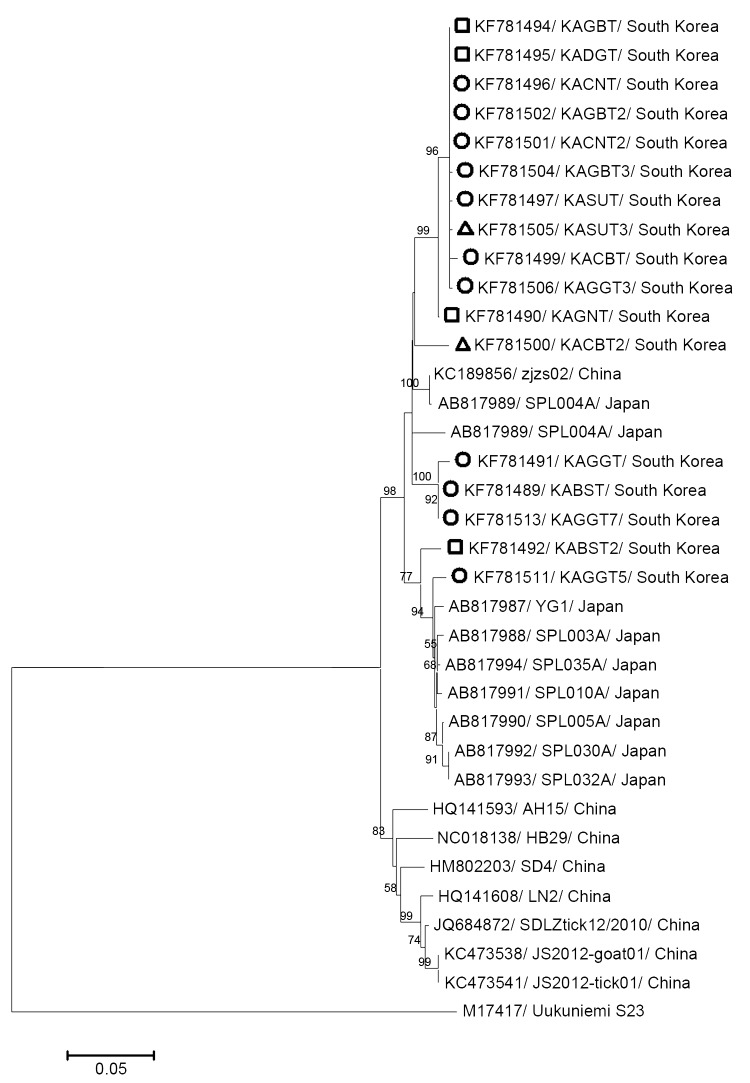

Sequences from the SFTSVs detected showed 92.3%–98.8% identity with the partial sequence of the M segment from 17 SFTSV strains from South Korea and from 17 other SFTSV strains from China and Japan. Using the neighbor-joining method, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on the partial M segment sequences (560 bp) obtained in this study and from SFTSV sequences in GenBank. The 17 strains from South Korea were closely related to the SFTSV strains from humans and ticks in China and Japan (Figure).

Figure.

Phylogenetic analysis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome viruses based on the partial medium segment sequences (560 bp). The tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining method based on the p-distance model in MEGA5 (12) (5,000 bootstrap replicates). Uukuniemi virus was used as the outgroup. Scale bar indicates the nucleotide substitutions per position. Among the 17 South Korean strains identified in this study, the Korean strains detected from Haemaphysalis longicornis, Amblyomma testudinarium, and Ixodes nipponensis ticks are marked with open circles, squares, and triangles, respectively. Numbers at nodes indicate bootstrap values.

Conclusions

H. longicornis ticks have been considered the principal tick vector of SFTSV; there is limited information on SFTSV infection by other tick species. On the basis of our findings, we propose that A. testudinarium and Ix. nipponensis ticks, from which we detected SFTSV, might serve as potential vectors of this virus in South Korea. However, the presence of viral RNA in a tick does not confirm that the tick can transmit the virus. To our knowledge, A. testudinarium and Ix. nipponensis ticks have not previously been considered as SFTSV vectors.

Further studies, including studies to isolate SFTSV from infected tick vectors and laboratory vector competence studies, are needed to confirm whether A. testudinarium and Ix. nipponensis ticks transmit SFTSV to humans. We attempted to isolate SFTSV from the SFTSV-positive ticks in our study by using Vero E6 cells but were unable to do so.

Adults and nymphs of Haemaphysalis and Ixodes spp. have been collected most frequently from humans, but larvae have not been collected. We did not detect SFTSV from adult male ticks in our study; however, the number of collected ticks was small. In another study in South Korea, ticks were collected from medium- and large-sized mammals (9), and the species and developmental stage of ticks in that study were similar to those in our study. In that study, H. longicornis and Ix. nipponensis ticks were most frequently found on wild boar, water deer, roe deer, raccoon dog, Siberian weasel, Asian badger, and leopard cat. Although A. testudinarium ticks were not collected from mammals in that study, we did collected them from humans in our study.

The prevalence of SFTSV in H. longicornis ticks in our study was 5.7%. In 27 other localities in 9 South Korean provinces, the mean SFTSV MIR of H. longicornis ticks collected by dragging or sweeping in the environment was 0.5% (S.-W. Park et al., unpub. data). In a study of SFTSV in China, 0.7%–5.4% of the tick population was positive for SFTSV (13). In the United States, 0.02% of field-collected ticks were positive for Heartland virus (14). The SFTSV MIR for ticks in Japan has not been reported.

Farmers and agricultural and forest workers from rural areas are at high risk for SFTS because their work environment increases their risk of contact with SFTSV-infected ticks (15). In our study, most ticks were collected from persons who lived in rural areas. Although 18 persons were bitten by ticks infected with SFTSV, not all of them had signs or symptoms of SFTS. This finding suggests that further studies are needed to obtain a detailed understanding of SFTS as an emerging tickborne viral disease and to develop preventive measures for the disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members at the Regional Health Institutes for the help they provided with this study.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (program no. 4800-4851-300-210-13).

Biography

Mr Yun is a senior researcher at the Division of Arboviruses, National Institute of Health, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. His research interests focus on tickborne viral diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Yun SM, Lee WG, Ryou J, Yang SC, Park SW, Roh JY, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in ticks collected from humans, South Korea, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Aug [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2008.131857

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, Liu Y, Li JD, Sun YL, et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1523–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, MacNeil A, Goldsmith CS, Metcalfe MG, et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:834–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa1203378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim K-H, Yi J, Kim G, Choi SJ, Jun KI, Kim N-H, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1892–4. 10.3201/eid1911.130792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi T, Maeda K, Suzuki T, Ishido A, Shigeoka T, Tominaga T, et al. The first identification and retrospective study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:816–27. 10.1093/infdis/jit603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ProMEDmail. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome—South Korea (05): additional fatalities. ProMed. 2013. Jul 6 [cited 2013 Oct 10]. http://www.promedmail.org, archive no. 20130706.1810682.

- 6.Liu Y, Li Q, Hu W, Wu J, Wang Y, Mei L, et al. Person-to-person transmission of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:156–60. 10.1089/vbz.2011.0758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao CJ, Guo XL, Qi X, Hu JL, Zhou MH, Varma JK, et al. A family cluster of infections by a newly recognized bunyavirus in eastern China, 2007: further evidence of person-to-person transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1208–14. 10.1093/cid/cir732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang YZ, Zhou DJ, Qin XC, Tian JH, Xiong Y, Wang JB, et al. The ecology, genetic diversity, and phylogeny of Huaiyangshan virus in China. J Virol. 2012;86:2864–8. 10.1128/JVI.06192-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HC, Han SH, Chong ST, Klein TA, Choi CY, Nam HY, et al. Ticks collected from selected mammalian hosts surveyed in the Republic of Korea during 2008–2009. Korean J Parasitol. 2011;49:331–5. 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.3.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chong ST, Kim HC, Lee IY, Kollars TM Jr, Sancho AR, Sames WJ, et al. Seasonal distribution of ticks in four habitats near the demilitarized zone, Gyeonggi-do (Province), Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:319–25. 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.3.319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguti N, Tipton VJ, Keegan HL, Toshioka S. Ticks of Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. Brigham Young Univ Sci Bull Biol Ser. 1971;15:1–226. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Chai C, Wang C, Am S, Lv H, He H, et al. Systematic review of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: virology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics. Rev Med Virol. 2014;24:90–102. 10.1002/rmv.1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savage HM, Godsey MS Jr, Lambert A, Panella NA, Burkhalter KL, Harmon JR, et al. First detection of Heartland virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) from field collected arthropods. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:445–52. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding F, Zhang W, Wang L, Hu W, Soares Magalhaes RJ, Sun H, et al. Epidemiologic features of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China, 2011–2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1682–3. 10.1093/cid/cit100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]