Abstract

New dialkylimidazole based sterol 14α-demethylase inhibitors were prepared and tested as potential anti-Trypanosoma cruzi agents. Previous studies had identified compound 2 as the most potent and selective inhibitor against parasite cultures. In addition, animal studies had demonstrated that compound 2 is highly efficacious in the acute model of the disease. However, compound 2 has a high molecular weight and high hydrophobicity, issues addressed here. Systematic modifications were carried out at four positions on the scaffold and several inhibitors were identified which are highly potent (EC50<1 nM) against T. cruzi in culture. The halogenated derivatives 36j, 36k, and 36p, display excellent activity against T.cruzi amastigotes, with reduced molecular weight and lipophilicity, and exhibit suitable physicochemical properties for an oral drug candidate.

Keywords: Trypanosoma cruzi, Sterol 14-alpha demethylase, CYP51, Chagas disease, Dialkylimidazole

Chagas disease (American Trypanosomiasis), caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is a leading cause of heart failure in Latin America. The disease is endemic throughout much of Mexico, Central and South America, with an estimated 8 million persons infected.1 Additionally, recent surveys suggest that 300,000 people in the United States, mostly immigrants, have Chagas disease.2 The disease has an acute and a chronic phase. In the latter the parasite can enter and destroy heart muscle cells, eventually resulting in death due to heart failure. The available drugs, benznidazole and nifurtimox, have debilitating side effects and exhibit low efficacy in the chronic stage of the disease.3 Hence, better drugs are desperately needed to treat Chagas disease, one of the most neglected tropical diseases.

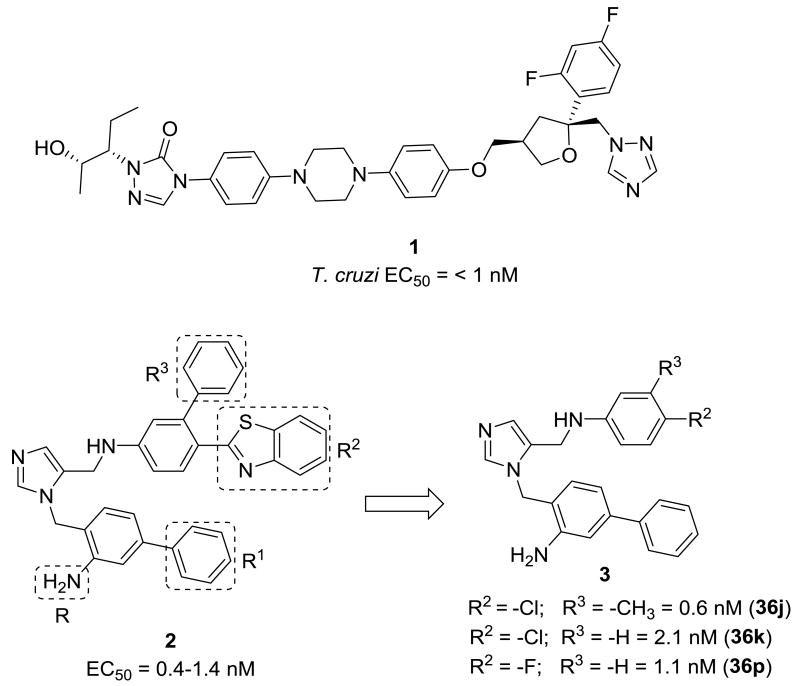

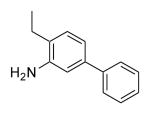

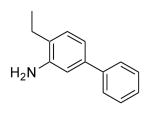

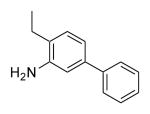

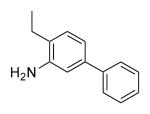

The antifungal drug posaconazole (1 in Figure 1), with an EC50 under 1 nM against T.cruzi in culture, is currently in clinical trials for Chagas disease, but if effective, high cost will likely limit widespread use.4 We have previously reported on low-cost dialkylimidazole compounds that kill T. cruzi amastigotes in the low nM range.5 The activity of these compounds is due to inhibition of the enzyme sterol 14α-demethylase6 (CYP51), essential for the biosynthesis of ergosterol-like sterols, crucial components of the parasite membrane.7 In the acute mouse model of Chagas disease, several dialkylimidazole compounds reduced parasitemia to microscopically undetectable levels after oral administration.5, 8 However, the compounds are relatively large, hence we attempted to reduce the size of our original lead 2 while maintaining potency to arrive at T. cruzi inhibitors like 3 with more drug-like physicochemical properties.

Figure 1. Most potent T cruzi Sterol-14alpha demethylase inhibitors.

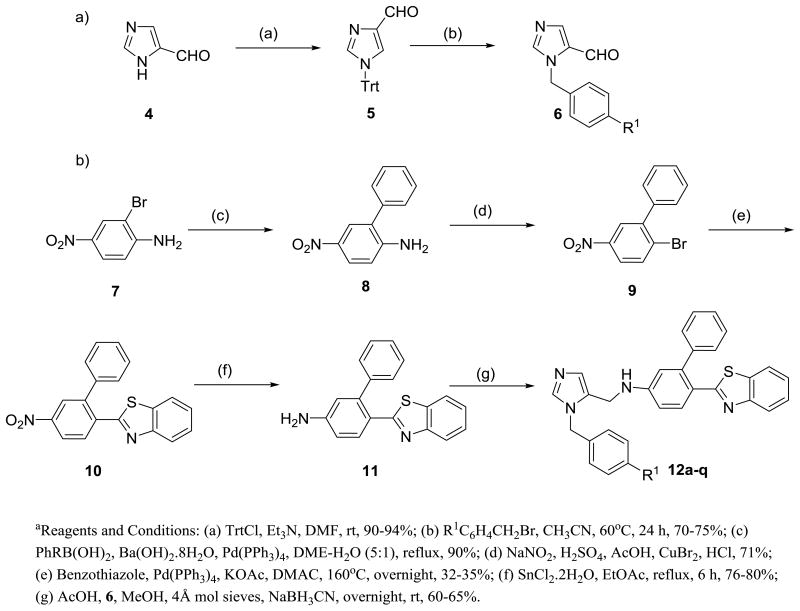

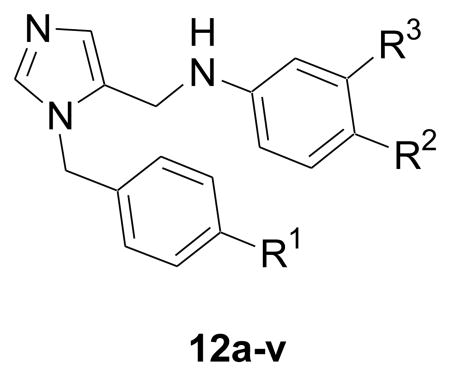

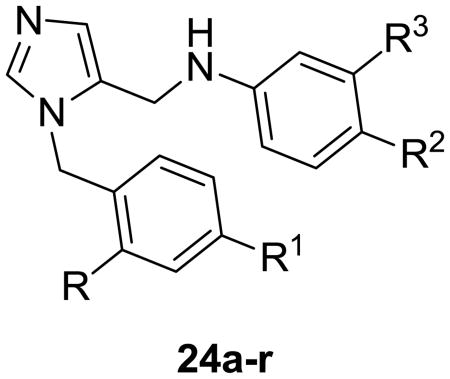

We previously reported a very simple and straightforward synthetic route to arrive at dialkylimidazoles in good yields.5 Synthesis requires the preparation of two fragments that are then coupled under reductive amination conditions. Analogs 12a-l were obtained according to Scheme 1. To generate the first fragment, trityl protected imidazole carboxaldehyde 5 was treated with substituted benzylbromides and subsequent deprotection resulted in substituted imidazole carboxaldehyde 6 in moderate to good yields varied depending on substituents on alkyl bromide. The second fragment 11 was derived from 7 using reported methods.5 Reductive coupling of key intermediates 11 and 6 provided the target compounds 12a-l.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of dialkylimidazole analogs a.

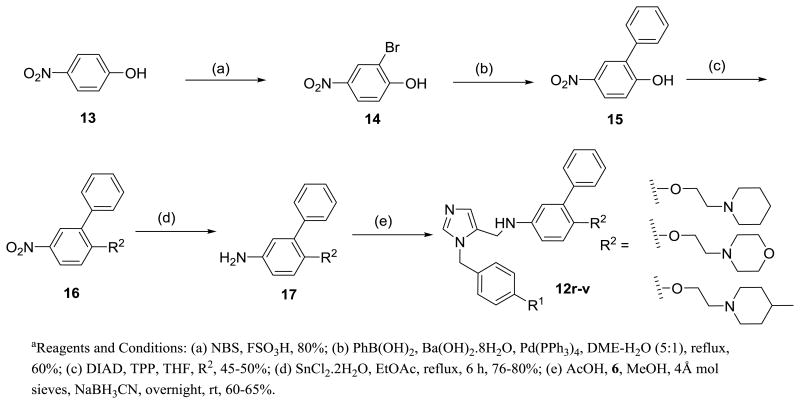

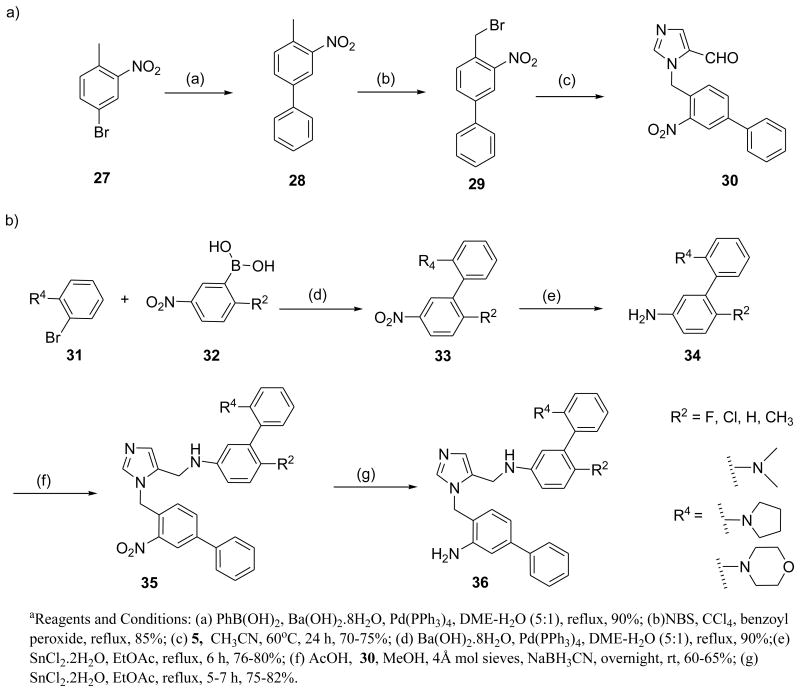

Preparation of analogs 12r-v is described in Scheme 2. Phenol derivatives 15 were reacted with alcohols in presence of DIAD and TPP in THF to generate 16 in approximately 45-50% yields. The intermediates were converted to the target compounds using the procedure described in Scheme 1. Synthesis of halogenated dialkylimidazole derivatives is depicted in Schemes 3 and 4. Compound 21 was synthesized as a versatile intermediate for the preparation of several analogs in this study. It was obtained inconsiderable yield from 18 by Suzuki coupling followed by bromination and further alkylation with 5.

Scheme 2. Preparation of dialkylimidazoles containing 2-ethoxy-morpholines and piperidinesa.

Scheme 3. Preparation of halogenated dialkylimidazoles a.

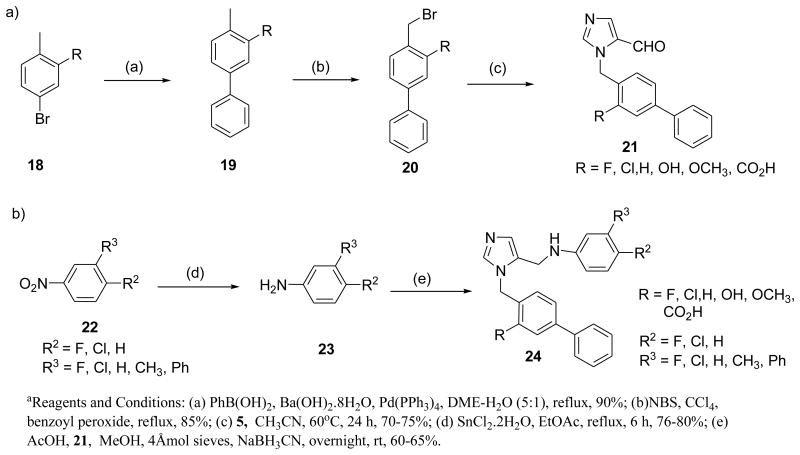

Scheme 4. Synthetic strategy for dialkylimidazole analogs bearing -NH2 at Ra.

The second fragment was readily prepared from available nitro derivatives. Fragments were coupled to generate the target compounds 24a-r in moderate to good yields. Similarly, all amino analogues were prepared as described in Scheme 4.

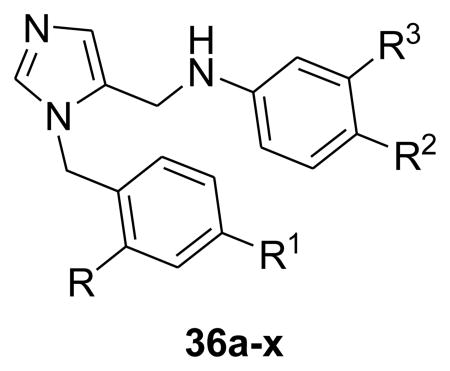

In our previous studies, inhibitors were potent but large and highly hydrophobic6. Hence we decided to produce simplified and more drug-like analogues with reduced molecular weight and lipophilicity (Table 1). We generated new structures by modifying 2 at four positions R, R1, R2 and R3 (Figure 1). All the synthesized analogs were tested against the clinically relevant amastigote stages of T. cruzi.9

Table 1. Activity of dialkylimidazoles with variations at R1, R2 and R3 against T. cruzi amastigotes.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Compd No. | MWT | logP | PSA | R1 | R2 | R3 | T. cruzi EC50(nM) |

|

| |||||||

| 12 | 548 | 8.4 | 42.7 | Phenyl | Benzb | Phenyl | 20.0 |

| 12a | 539 | 7.4 | 55.9 | 2-Furan | Benz | Phenyl | 21.2 |

| 12b | 550 | 7.5 | 55.6 | 2-Pyridine | Benz | Phenyl | 19.3 |

| 12c | 555 | 8.2 | 42.7 | 2-Thiophene | Benz | Phenyl | 11.1 |

| 12d | 564 | 7.6 | 68.8 | 2-NH2-Ph | Benz | Phenyl | 75.4 |

| 12e | 565 | 8.1 | 63.0 | 2-OH-Ph | Benz | Phenyl | 123.2 |

| 12f | 563 | 8.9 | 42.7 | 4-Me-Ph | Benz | Phenyl | 50.0 |

| 12g | 583 | 9.0 | 42.7 | 4-Cl-Ph | Benz | Phenyl | 48.5 |

| 12h | 563 | 8.9 | 42.7 | 3-Me-Ph | Benz | Phenyl | 5.4 |

| 12i | 565 | 8.1 | 63.0 | Ph | Benz | 4-OH-Ph | 11.0 (20,010)a |

| 12j | 579 | 8.2 | 52.0 | Ph | Benz | 4-OMe-Ph | 10.0 |

| 12k | 564 | 7.6 | 68.8 | Ph | Benz | 4-NH2-Ph | 1.6 (27,500)a |

| 12l | 574 | 8.2 | 66.5 | Ph | Benz | 4-CN-Ph | 32.0 |

| 12m | 466 | 7.0 | 29.9 | Ph | Methyl | 2,6-Di-F-Ph | 36.6 |

| 12n | 451 | 5.6 | 42.7 | Ph | Chloro | 4-Pyridine | 27.2 |

| 12o | 439 | 5.6 | 34.8 | Ph | Chloro | Pyrrole | 30.4 |

| 12p | 457 | 6.1 | 33.1 | Ph | Chloro | Piperidine | 53.6 |

| 12q | 451 | 5.6 | 42.7 | Ph | Chloro | 3-Pyridine | 64.8 |

| 12r | 545 | 5.9 | 51.6 | Ph | -O(CH2)2-Morc | Phenyl | 35.2 |

| 12s | 544 | 5.9 | 54.4 | Ph | -NH(CH2)2-Mor | Phenyl | 115.2 |

| 12t | 543 | 6.9 | 42.3 | Ph | -O(CH2)2-Pipd | Phenyl | 316.8 |

| 12u | 542 | 6.6 | 45.1 | Ph | -NH(CH2)2- Pip | Phenyl | 194.0 (10,700)a |

| 12v | 558 | 5.9 | 45.6 | Ph | -O(CH2)2-4-Me-Pip | Phenyl | 97.4 (4,470)a |

Host cell activity against CRL-8155 IC50 (nM);

benzothiazole.

morpholine.

piperidine.

Initial modifications at R1 in compound 12 replaced the phenyl group with various heterocycles like furan, pyridine and thiophene (12a-c), which consequently, did little to modulate activity against T. cruzi. However, introduction of polar functionality at the 2 position on R1 or lipophilic groups at the 4 position on R1 (12d-g) was less well tolerated.

We next investigated the effect of substitution on the R3 phenyl system. Introduction of polar functional groups at the para position on the terminal phenyl (R3) such as hydroxy and methoxy and had little effect on potency. However, the introduction of an amino group at the 4-position on R3 (12k) dramatically inhibited the T. cruzi cultures at low nanomolar level with >10‐fold increase in potency (EC50=1.6 nM) compared with compound 12.

Previously explored SAR of the benzothiazole moiety 6 suggested that benzothiazole is at the periphery of the active site, partially exposed to solvent. Replacing it by a simple chloro retains the potency against T. cruzi and, importantly, reduces the molecular mass by 100.6 By retaining −Cl at R2 position, we obtained an extra molecular mass window within Lipinski space to explore R3 with a variety of heterocyclic as well as saturated heterocyclic systems (12n-q). However, associated modifications did not improve potency. In addition, replacement of the benzothiazole moiety at R2 with alkoxy and alkylamino linked heterocycles, (12r-v), displayed as much as a 10‐fold drop in potency. These analogues suggest a limited tolerance at R3 for further modifications containing large, flexible linked heterocycles.

Considering the dialkyl imidazole core, we began to focus our attention on smaller functional groups at the R2 and R3 positions, to try to further improve physicochemical properties, whilst improving or at least, retaining potency against T. cruzi amastigotes (Table 2). Furthermore, we investigated the importance of the −NH2 group on the biphenyl rings of the imidazole subunit, for activity against T.cruzi. Two of the most potent compounds from previous studies6 both comprise an amino functionality at the C-2 position of the biphenyl attached to the imidazole. The introduction of the C-2 amino functionality to compound 12 to afford compound 2 resulted in a 20‐fold increase in potency. The development of an in-house homology model of T.cruzi CYP51, using the previously published Mycobacterium tuberculosis crystal structure,10 has shown that this remarkable increase in activity can be attributed to a key H-bond interaction of the aniline moiety with a histidine residue in the active site of T.cruzi CYP51. However, replacement of the aniline moiety with other functional groups such as -OMe (24n), -OH (24o) and -COOH (24q), led to a >27-fold drop in potency, highlighting the importance of this key amino/histidine interaction. Compounds such as 24a and 24o, without the aniline moiety, also exhibited sub-20 nM activity against T.cruzi. Interestingly, compound 24a demonstrated that the benzothiazole moiety at the R2 position could be replaced with only an F atom, albeit with the aniline moiety also replaced with an F atom. However, the changes highlighted by compound 24a compared with compound 12, showed that small, lipophilic groups at R2 were well tolerated, thus reducing molecular weight and logP whilst retaining activity. In addition, desirable levels of potency could be attained by the introduction of a combination of halogen atoms at R, R1, R2 and R3, whilst still retaining sub-100 nM levels of potency against T.cruzi.

Table 2. Activity of halogenated dialkylimidazoles against T. cruzi amastigotes.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Compd No. | MWT | logP | PSA | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | T. cruzi EC50(nM) |

|

| ||||||||

| 12 | 548 | 8.4 | 42.7 | H | Phenyl | Benzb | Phenyl | 20.0 |

| 2 | 564 | 7.6 | 68.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | Benz | Phenyl | 1.0 |

| 24a | 451 | 6.5 | 29.9 | F | Phenyl | F | Phenyl | 12.0 |

| 24b | 375 | 4.8 | 29.9 | F | Phenyl | F | H | 70.2 |

| 24c | 380 | 5.3 | 29.9 | F | Phenyl | F | Methyl | 53.0 |

| 24d | 409 | 5.4 | 29.9 | F | Phenyl | F | Cl | 49.0 |

| 24e | 393 | 5.0 | 29.9 | F | Phenyl | F | F | 46.0 |

| 24f | 331 | 3.8 | 29.9 | F | Fluoro | F | Methyl | 272.0 |

| 24g | 335 | 3.5 | 29.9 | F | Fluoro | F | F | 212.0 |

| 24h | 317 | 3.3 | 29.9 | F | Fluoro | F | H | 354.0 |

| 24i | 408 | 5.7 | 29.9 | Cl | Phenyl | -Cl | H | 83.2 |

| 24j | 405 | 5.8 | 29.9 | Cl | Phenyl | F | Methyl | 26.0 |

| 24k | 426 | 5.9 | 29.9 | Cl | Phenyl | F | Cl | 48.7 |

| 24l | 409 | 5.4 | 29.9 | Cl | Phenyl | F | F | 38.1 |

| 24m | 469 | 6.6 | 29.9 | H | Phenyl | F | 2,6-di-F-Phe | 11.7 (17,460)a |

| 24n | 480 | 6.6 | 39.1 | OCH3 | Phenyl | Cl | Phenyl | 35.1 |

| 24o | 465 | 6.5 | 50.1 | OH | Phenyl | Cl | Phenyl | 5.9 (21,500) |

| 24p | 564 | 8.0 | 63.0 | OH | Phenyl | Benzb | Phenyl | 89.3 |

| 24q | 592 | 7.2 | 80.0 | CO2H | Phenyl | Benz | Phenyl | >1000 |

| 24r | 579 | 8.2 | 52.0 | OCH3 | Phenyl | Benz | Phenyl | 27.2 |

Host cell activity against CRL-8155 IC50 (nM);

benzothiazole.

Also worthy of note is compound 24b in which the phenyl at R3 was replaced with hydrogen, resulting in less than 4-fold drop in potency compared with compound 12, against T. cruzi, supporting the fact that smaller lipophilic groups were well tolerated at R2 and R3. With this information in hand, a small set of chlorinated analogs (24i-l) were designed and tested against T. cruzi cultures. The comparable potencies of analogues 24a-l suggest that all of these analogues adopt similar binding conformations. In addition, a combination of fluorine and chlorine atoms at R1, R2 and R3 could be utilized to reduce molecular weight and logP, thus improving physicochemical properties, whilst retaining activity against T.cruzi.

We also examined other aromatic substituents to replace the aniline moiety (24n-r) as described in Table 2. Compound 24o showed considerable improvements in potency (EC50 of 5.9 nM) compared with the compounds in the same series, which lack the amino group on the biphenyl imidazole sub unit, suggesting that replacement of the amino group with alternative small, hydrogen bond donors, may be tolerated. However, the larger, deactivating substituent −COOH group (24q) was not tolerated. These studies suggest some flexibility in the functionality placed at the R position, with a preference for small H-bond donor groups.

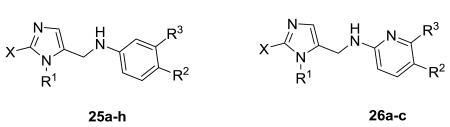

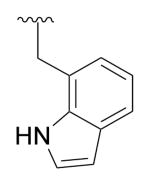

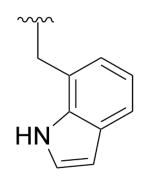

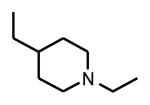

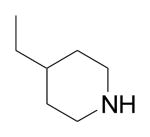

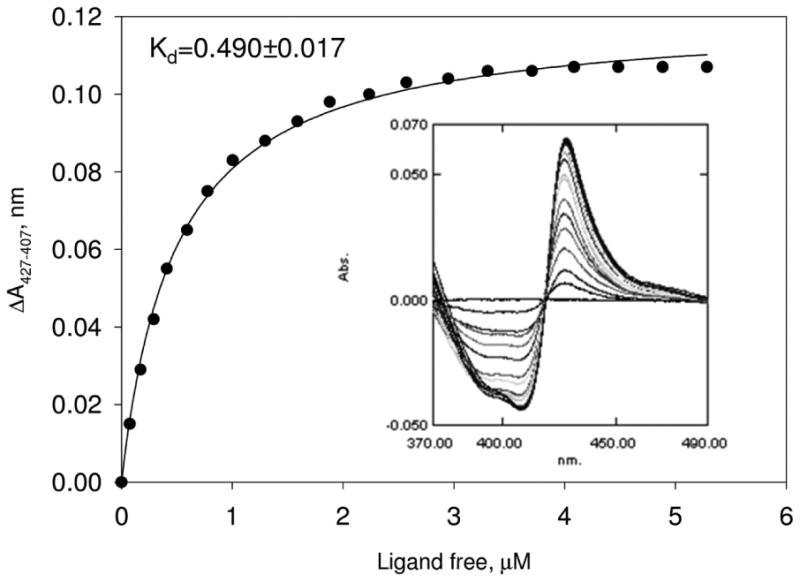

Alternative functional groups were also investigated to try to optimize the potency against T. cruzi (Table 3). Methylation at C-2 position of the imidazole (25a-d) did not show activity even at 1 μM. The idea was to prevent the binding of the imidazole to human CYP's but this series was discarded due to dramatic loss in potency, highlighting the importance of the imidazole-nitrogen binding interaction to the heme moiety in the T.cruzi CYP51 active site for activity. Replacement of the biphenyl on the imidazole by ethyl piperidines and indole derivatives (25e-h) was not tolerated. These results also demonstrate the critical requirement of the biphenyl system attached to the imidazole subunit. However, potent analogues were also observed when the central phenyl ring was replaced with pyridine. Replacement of pyridine and keeping the biphenyl moiety on the imidazole (26b) showed activity at 12.5 nM against T. cruzi and further addition of an amino group on biphenylimidazole (26c) led to an EC50 of 0.2 nM. Inhibition of the proposed biological target by the dialkylimidazole series was confirmed by spectrophotometric studies. Using recombinant T. cruzi sterol 14α-demethylase, we have previously shown that 26c binds to the haem moiety in the CYP51 active site as characterized by a Soret Type II binding spectra (Fig. 2).6

Table 3. Activity of dialkylimidazoles varied at X, R1, R2 and R3 positions and Pyridine based dialkylimidazoles against T. cruzi.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Compd No. | MWT | logP | PSA | x | R1 | R2 | R3 | T. cruzi EC50(nM) |

|

| ||||||||

| 25a | 404 | 4.1 | 55.8 | Me |

|

F | F | >1000 |

| 25b | 400 | 4.5 | 55.8 | Me |

|

F | Me | >1000 |

| 25c | 420 | 4.6 | 55.8 | Me |

|

F | Cl | >1000 |

| 25d | 386 | 4.0 | 55.8 | Me |

|

F | H | >1000 |

| 25e | 396 | 4.8 | 45.6 | H |

|

F | Phenyl | 333.0 |

| 25f | 412 | 5.2 | 45.6 | H |

|

Cl | Phenyl | 333.0 |

| 25g | 408 | 4.3 | 33.0 | H |

|

Cl | Phenyl | >1000(17,400)a |

| 25h | 380 | 3.5 | 41.8 | H |

|

Cl | Phenyl | >1000 |

| 26a | 370 | 4.2 | 52.0 | H |

|

OMe | Phenyl | 686.1 |

| 26b | 446 | 5.8 | 52.0 | H |

|

OMe | Phenyl | 12.5 |

| 26c | 461 | 5.0 | 78.0 | H |

|

OMe | Phenyl | 0.2 (>5000)a |

Host cell activity against CRL-8155 IC50 (nM);

Figure 2. Spectral response of T. cruzi CYP51 to 26c.

Titration curve and difference binding spectra (inset). P450 concentration was 2.2 μM; 26c titration range 0.4-7.6 μM (titration steps of 0.4 μM). Methods as described previously.6

Utilizing compound 26c as a reference point for further synthetic modifications, we initially replaced the methoxy at R2 with the metabolically more stable fluorine group (36n) to evaluate the effects of further modifications at R3. Modifications at R3 with the larger chlorine atom at the R2 position were also investigated (Table 4).

Table 4. In vitro anti-T. cruzi activities of highly potent dialkylimidazole analogs bearing –NH2 at R (Scheme 4).

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Compd No. | MWT | logP | PSA | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | T. cruzi EC50(nM) |

|

| ||||||||

| 26c | 461 | 5.0 | 78.0 | NH2 | Phenyl | OMe | Phenyl | 0.2 |

| 36a | 534 | 6.5 | 59.1 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | 2-Pyrroe-phe | 87.0 |

| 36b | 550 | 5.9 | 68.3 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | 2-Mor-phe | 24.5 |

| 36c | 449 | 4.7 | 68.7 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | 2-Pip-phe | 20.8 |

| 36d | 508 | 6.1 | 59.1 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | 2-N,N-Di-Me-Phe | 19.0 |

| 36e | 480 | 5.1 | 81.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | 4-NH2-Phe | 0.3(12,900)a |

| 36f | 423 | 5.0 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | Cl | 9.0 |

| 36g | 472 | 5.3 | 59.1 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | Pipd | 1.1(>5,000)a |

| 36h | 454 | 3.5 | 73.7 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | Imidazole | 5.0 14,600)a |

| 36i | 453 | 4.8 | 60.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | Pyrrole | 3.8 |

| 36j | 386 | 4.4 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | Methyl | 0.6 12,900)a |

| 36k | 388 | 4.3 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | Cl | H | 2.1 |

| 36l | 484 | 5.8 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | -F | 2,6-di-F -Phe | 0.4 |

| 36m | 388 | 4.3 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | F | Cl | 1.2 |

| 36n | 448 | 5.5 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | F | Phenyl | 0.8(18,800)a |

| 36o | 390 | 4.0 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | F | F | 3.2 |

| 36p | 372 | 3.8 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | F | H | 1.1 |

| 36q | 480 | 6.2 | 55.8 | NH2 | Phenyl | methyl | 2,6-di-F-Phe | 0.4 >5,000)a |

| 36r | ND | ND | ND | NH2 | Phenyl | O(CH2)2-morb | 4-Cl-Phe | 1.5 |

| 36s | 572 | 5.1 | 71.5 | NH2 | 2-Pyridine | O(CH2)2-4-Me pipc | Phenyl | 5.8 (5270)a |

| 36t | ND | ND | ND | NH2 | Cl | Benzd | Phenyl | 1.4 |

| 36u | 449 | 4.7 | 68.7 | NH2 | Methoxy | F | Phenyl | 14.5 |

| 36v | 406 | 4.5 | 55.8 | NH2 | Cl | F | Phenyl | 12.8 |

| 36w | 372 | 3.8 | 55.8 | NH2 | H | F | Phenyl | 232.6 |

| 36x | 399 | 2.2 | 68.3 | NH2 | Morpholine | F | F | 358.0 |

Host cell activity against CRL-8155 IC50 (nM);

benzothiazole.

morpholine.

piperidine.

pyrrolidine.

Modification of the phenyl ring at R3 with saturated ring systems was poorly tolerated. However, direct replacement of the phenyl ring at R3 with −Cl (36f), imidazole (36h) and pyrrole (36i), also displayed sub10 nM levels of potency against T.cruzi.

The most potent analogues against T. cruzi were observed when the phenyl at R3 was replaced with minimalistic groups such as −CH3 (36j) and −H (36k). In addition, both examples indicate that the size of groups at R3 can be significantly reduced, while still retaining activity against T.cruzi amastigotes. Furthermore, similar observations were made in the case of fluorinated analogs. It is well known that incorporation of fluorine into a drug allows simultaneous modulation of electronic, lipophilic and steric parameters all of which can critically influence the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs.11 In this context several fluorinated dialkylimidazole based sterol 14α-demethylase inhibitors were synthesized and evaluated. All the synthesized fluoro analogues showed excellent potency against T. cruzi. Remarkably, compound 36p, in which R3 phenyl group was removed completely, still exhibited high potency of 1.1 nM.

As can be seen in Table 4, the majority of analogues prepared were found to be extremely active with EC50 values of < 1 nM. This is a considerable improvement in potency in this series leading to anti-T. cruzi activity comparable to that of posaconazole (1). The current SAR study clearly shows that 2-amino biphenyl as R-R1 system is superior for potency and also that halogens (-F, -Cl) are well tolerated at the R2 position.

Twelve of the more potent compounds in this series were tested for cytotoxicity to the mammalian lymphocytic cell line CRL-8155. This is a relatively sensitive cell line to the cytotoxic effects of chemicals.12 The tested dialkylimidazoles were only cytotoxic at relatively high concentrations in the range of 5-10 μM demonstrating a selectivity margin over T. cruzi amastigotes of >10,000-fold in many cases.

Overall in this study we synthesized 75 dialkylimidazole-based inhibitors of sterol-14α -demethylase and evaluated them against T. cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease. We previously reported that, dialkylimidazole based inhibitors are well tolerated in animals infected with acute stage of the disease. These new analogues are structurally simple, display suitable physicochemical properties for that of an oral drug candidate and can be efficiently synthesized at low-cost. In addition, novel compounds reported herein display excellent potency against T.cruzi amastigotes with activity comparable to posaconazole and show potential as novel therapeutics for the treatment of Chagas disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Mammalian cell cytotoxicity experiments were assisted by Nicole A. Duster. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AI070218, AI054384, and GM067871. We appreciatively acknowledge the financial support for this project from Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi). For the work described in this paper, DNDi allocated non-earmarked funding (Department for International Development (DFID)/United Kingdom, Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID)/Spain, Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders)/International). The donors had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References and notes

- 1.Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:342. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Montgomery SP. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e52. doi: 10.1086/605091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Coura JR, De Castro SL. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:3. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000700001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McKerrow JH, Doyle PS, Engel JC, Podust LM, Robertson SA, Ferreira R, Saxton T, Arkin M, Kerr ID, Brinen LS, Craik CS. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(Suppl 1):263. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000900034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leslie MD. Science. 2011;333:933. doi: 10.1126/science.333.6045.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suryadevara PK, Olepu S, Lockman JW, Ohkanda J, Karimi M, Verlinde CLMJ, Kraus JM, Schoepe J, Van Voorhis WC, Hamilton AD, Buckner FS, Gelb MHJ. Med Chem. 2009;52:3703. doi: 10.1021/jm900030h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepesheva GI, Zaitseva NG, Nes WD, Zhou W, Arase M, Liu J, Hill GC, Waterman MRJ. Biol Chem. 2006;281:3577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Majumder HK. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;625:vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Urbina JA, Docampo R. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:495. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckner F, Yokoyama K, Lockman J, Aikenhead K, Ohkanda J, Sadilek M, Sebti S, Van Voorhis WC, Hamilton AD, Gelb MH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535442100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckner FS, Verlinde CLMJ, La Flamme AC, Van Voorhis WC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2592. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hucke O, Gelb MH, Verlinde CLMJ, Buckner FSJ. Med Chem. 2005;48:5415. doi: 10.1021/jm050441z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patidar AK, Selvam G, Jeyakandan M, Mobiya AK, Bagherwal A, Sanadya G, Mehta R. Int J Drug Des Discovery. 2011;2:458. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shibata S, Gillespie JR, Ranade RM, Koh CY, Kim JE, Laydbak JU, Zucker FH, Hol WGJ, Verlinde CLMJ, Buckner FS, Fan EJ. Med Chem. 2012;55:6342. doi: 10.1021/jm300303e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.