Abstract

Many caregivers continue to provide care and support to their care recipients after institutional placement. A two-group randomized controlled trial was carried out to test the efficacy of a psychosocial intervention for informal caregivers whose care recipients resided in a long-term care facility. The intervention was delivered during the 6 month period following baseline assessment. Follow-up assessments were carried out at 6, 12, and 18 months. Primary outcomes were caregiver depression, anxiety, burden, and complicated grief. Significant time effects were found for all three primary outcomes showing that caregiver depression, anxiety, and burden improved over time. No treatment effects were found for these outcomes. However, complicated grief was significantly lower for caregivers in the treatment condition.

Keywords: caregiving, complicated grief, long-term care

INTRODUCTION

Placement in a long-term care facility is a common experience for many families and their older adult members. The typical nursing home placement results from a cascade of cognitive and physical decline, often punctuated by an acute medical event (Gaugler, Duval, Anderson & Kane, 2007). Placement in a nursing home is commonly viewed as a stressful experience for the resident, as it often involves loss of privacy, limits on independence, and decreased autonomy. Adaptation to new surroundings is often difficult for the resident, resulting in a worsening of health and emotional problems, as well as iatrogenic events such as falls or infections.

The institutionalization experience also takes a toll on family members involved in this process. Cross-sectional studies of caregivers of institutionalized relatives (Davies & Nolan, 2004; Kaplan & Boss, 1999; Lindman Port, 2004; Montgomery & Kosloski, 1994; Tornatore & Grant, 2002; Whitlatch, Schur, Noelker, Ejaz, & Looman, 2001), as well as longitudinal studies of the institutionalization transition (Zarit & Whitlatch, 1992; Gaugler, Anderson, Zarit, & Pearlin, 2004; Gaugler & Holmes, 2003), challenge the myth that family members abandon their elderly relatives admitted to a long-term care facility. The majority of caregivers visit their relative on a regular basis (Yamamoto-Mitani, Aneshensel, & Levy-Storms, 2002; Keefe & Fancey, 2000) and perform tasks similar to those carried out when the care recipient was living at home, such as feeding, grooming, managing money, shopping, and providing transportation. One recent study found that more than half of family caregivers monitored, managed care, and assisted with meals, and 40% assisted with personal care tasks (Williams, Zimmerman, & Williams, 2012). In addition, caregivers take on new tasks such as interacting with administration and staff of the facility as the advocate for the residents (Friedemann, Montgomery, Maiberger, & Smith, 1997; Ryan & Scullion, 2000). Family caregiver depressive symptoms and anxiety persist with similar severity as when they were providing in-home care, and anxiolytic use has been found to increase pre- to post-placement (Schulz et al., 2004). Indeed, the greater the hands-on care provided by the family caregiver, the higher their distress, and the lower their satisfaction with care provided by the nursing home staff (Tornatore & Grant, 2004). Causes of distress among caregivers include inadequate resident personal care, lack of communication with nursing home physicians, and challenges of surrogate decision-making, including the need for education to support advance care planning and end-of-life decisions (Givens, Lopez, Mazor, & Mitchell, 2012). These findings suggest that caregivers of recently placed residents could benefit from interventions that provide emotional support, education about nursing home procedures, and information about patient prognosis and advanced care planning. Numerous studies have documented that family involvement in caring for residents in long-term care facilities is prevalent and has consequences for the resident and caregiver (Gaugler, 2005; Grabowski & Mitchell, 2009; Givens, Prigerson, Jones, & Mitchell, 2011), but little is known about the best way to support caregivers during this phase of their caregiving careers.

Intervention studies targeting family members of placed long-term care residents are rare, and the results are mixed. Two studies examined post-placement caregiver outcomes in which the primary goal was to test caregiver interventions (e.g., counseling, multi-component psychosocial intervention) designed to alleviate the burden of in-home caregiving. One study reported small positive effects on burden and depression among caregivers in the treatment group when compared to the control group after the care recipient was placed in a long-term care facility (Gaugler, Roth, Haley, & Mittelman, 2008), while another study found no differences between treatment and control subjects after care recipients were placed (Schulz et al., 2004). Several research groups have reported results from studies in which family members of residents in long-term care facilities along with staff are provided training on communication and conflict-resolution techniques, or education on interacting with dementia patients. In these studies both caregivers and staff are included in outcomes assessment, and they generally achieve their stated goals of improving family member communication with staff (Robison et al., 2007; Pillemer, Hegeman, Albright, & Henderson, 1998; Pillemer et al., 2003) and the way family members and other visitors communicate with residents (McCallion, Toseland, & Freeman, 1999). However they have little impact on the emotional well-being of caregivers. We found only one study that specifically targeted the emotional well-being of the caregiver using a telephone-delivered psychosocial intervention (Davis, Tremont, Bishop, & Fortinsky, 2011). Researchers found significant treatment effects on feelings of guilt related to placement but no effects for depression, burden, or facility satisfaction. These results should be viewed cautiously as the sample size was small, and there were large differences between treatment and control groups at baseline on the primary outcome measures which were not adjusted for in the outcomes analysis. Taken together, the existing research has a number of limitations: all studies focused exclusively on caregivers of institutionalized dementia patients, only a few tested the efficacy of interventions specifically designed for family members of institutionalized residents, and the effects on well-being of caregivers have been inconsistent.

The purpose of this paper is to report the results of a randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of a caregiver intervention for family members who recently placed their relative in a nursing home. The intervention is based on a broad conceptual framework that argues that the effects of institutionalization on the family caregiver are shaped by individual vulnerabilities and resources that affect the response to caregiving more generally, and a set of stressors that are uniquely associated with placement. The latter category includes reduced control over care provided their relative, possible reductions in the quality of care, challenges of navigating an unfamiliar organizational system, increased suffering and accelerated decline in the care recipient, and feelings of guilt at having failed or abandoned their relative. The intervention developed for this study was designed to address three characteristic needs of family caregivers who recently placed their relative: (1) psychiatric problems, particularly depression and anxiety, which are common among caregivers who recently placed their relative; (2) knowledge about the long-term care procedures and resident trajectories; and (3) end-of-life care planning for the institutionalized relative. These needs were addressed with an intervention that had three components: (1) systematic screening of psychiatric status and a treatment protocol for depressive symptoms, major depression, and anxiety; (2) education about the organization and operating procedures of long-term care facilities and a negotiated plan for caregiver participation in the care of their relative; and (3) education about resident trajectories in long-term care and assistance with end-of life planning. Expected outcomes include reduced depression and anxiety, greater satisfaction with the long-term care facility, and reduced resident service use (e.g., hospitalizations) because of an articulated end-of-life plan. In addition, because this intervention was designed to reduce distress prior to the death of the placed relative, a risk factor for negative bereavement outcomes (Schulz, Boerner, & Hebert, 2008), we also expected lower levels complicated grief post-death among persons in the active treatment compared to the control condition.

METHODS

Study Design Overview

The study design was a two-group, randomized controlled trial comparing an active intervention condition to an information-only control condition. Family caregivers were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: (1) in the active intervention condition, family caregivers of recently placed residents received a multi-component intervention designed to target three areas of need – knowledge and procedures of nursing homes, advanced care planning, emotional well-being; and (2) in the information-only control condition, family caregivers of recently-placed residents received treatment as usual with the addition of written documents on where to find information in the areas of need identified for the active treatment intervention. The intervention was delivered during a 6 month period following baseline assessment and randomization. Caregiver follow-up assessments were carried out at 6, 12, and 18 months after the baseline assessment. Interventionists could not serve as assessors in the study, and assessors were blind to participant assignment to condition.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh. A Data Safety Monitoring Board met at regular intervals throughout the study to monitor adverse events (e.g., high depression scores, severe caregiver medical problems/events) potentially associated with study participation.

Eligibility Criteria, Recruitment and Retention

The caregiver was self-identified as the individual providing the most instrumental and emotional support to the resident prior to placement. Dyads (caregiver and resident) were eligible for entry if the caregiver: (1) was a family member/partner (e.g., spouse, child, or fictive kin); (2) was 21 years of age or older; (3) provided a minimum of 3 months of in-home care prior to institutionalization; (4) spoke English; and (5) planned to live in the area for at least 6 months. The care recipient/resident: (1) had to be 50 years of age or older; (2) have been permanently placed within a long-term care facility within the last 120 days; and (3) be impaired in at least 3 of 6 activities of daily living (ADL). Dyads were excluded if the care recipient was enrolled in a hospice program at the time of recruitment. The goal of these inclusion/exclusion criteria was to recruit a sample of caregivers who recently placed their relative in a long-term care facility with low probability that the resident would be returned to a community setting.

Participants were recruited from 16 long-term care facilities in Western Pennsylvania. The majority of participants were recruited with the help of clinical social workers and nurses at participating facilities who introduced the study to newly admitted residents and their families to determine their willingness to be called by study staff. Study recruiters contacted families by phone and administered a brief telephone screening to determine eligibility. If the eligible caregiver expressed interest in the study, an appointment was made for a home visit. At the home visit, caregivers were given a full description of the study and were asked to provide written informed consent. After obtaining family caregiver consent, residents deemed competent to provide informed consent were approached to sign the resident consent form, which permitted access to nursing home medical records pertaining to the participating resident. For residents who were unable to give informed consent, their legal surrogate (usually the family caregiver) was asked to give consent in their stead. If the family caregiver was willing to participate, and the competent resident was unwilling, the family caregiver was still eligible to be in the study, although resident information could not be used in this case.

A total of 317 dyads were screened. Of these, 52 were ineligible and 48 withheld consent, leaving 217 who completed the baseline assessment and were subsequently randomized to either control (n = 108) or intervention (n = 109) conditions; 204 caregivers completed the 6 month assessment, 191 completed the 12 month assessment, and 190 completed the 18 month assessment. Retention did not vary by group assignment. Twelve caregivers assigned to the Control Condition withdrew from the study, and 14 caregivers from the Intervention Condition withdrew from the study. A total of 89 resident care recipients died in the course of the study (48 in the Control Condition and 41 in the Intervention Condition); these caregivers continued to be followed-up after the death of their care recipient using an abbreviated assessment.

Study Intervention

The intervention, modeled after Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) (Belle et al., 2006), used multiple treatment modalities and a range of strategies and techniques to address three characteristic needs of family caregivers who recently placed their relative: (1) knowledge about the nature of long-term care procedures and resident trajectories; (2) advanced and end-of-life care planning for the institutionalized relative; and (3) caregiver emotional problems, particularly depression and anxiety which are common among caregivers who recently placed their relative.

Three modules (see Table 1), each with multiple components, were developed to address these needs. Module 1 provided basic knowledge about nursing home organization and procedures, the role of family members in nursing homes, legal and financial issues, and clinical issues regarding the resident. Module 2 focused on advanced care planning and included training on living wills, durable power of attorney, and communication between caregiver, care recipient, and physician. Module 3 was designed to improve the emotional well-being of family caregivers and focused on stress reduction, managing mood, and enhancing pleasant events.

Table 1.

Components and Content of Intervention

| 1. Basic Knowledge (3 Sessions) | Content |

| Preliminary questions | Establish degree to which family caregivers have knowledge of nursing home procedures, legal and financial issues, and clinical issues regarding the resident. |

| Family involvement | Knowledge about nursing home organization and procedures, role of family members, care conferences, delivering constructive criticism, and taking care of yourself. |

| Legal and financial issues | Nursing home funding, the role of Medicare and Medicaid, inspections and licensure, resident rights, reporting violations, problems and complaints. |

| Clinical issues | |

| Falls | Risk factors, assessing risks, restraints, family involvement. |

| Skin care | Pressure ulcers and their causes, prevention of pressure ulcers loss of sensation/ immobility; skin types, family involvement. |

| Infections | Transmission and prevention. |

| Nutrition | Nutrition and other specialists involved in assuring proper nutrition; effects of dementia, family involvement. |

| Dementia (optional) | Types of dementia, disease progression, problem behaviors, depression, delirium paranoia/false beliefs, pain, treatment, working with staff. |

| 2. Advanced Care Planning (4 Sessions) | Content |

| Preliminary questionnaire | Establish degree to which caregivers are aware of care recipient end-of-life care preferences and whether advance directives are in place. |

| Computer-video and information packet | Contains definitions of terms; description of the Resident Selt-Determination Act; Pennsylvania state forms and instructions for advance directives; examples of living will formats; and ways to approach end-of-life care decision-making (Values History Questionnaire; Conversations Before the Crisis). |

| Living wills | Decisions about intensity of treatment and desired levels of resident functioning; potential interventions and scenarios (nutrition, hydration, CPR, ventilation, transfusion, surgery, dialysis, antibiotics, chemotherapy, invasive procedures, and hospitalization), pain management and consciousness, organ donation, death setting, degree of diminished capacity used to activate advance directives. |

| Durable power of attorney | Roles and responsibilities regarding diagnosis and treatment; hiring and discharging of providers; consent to palliative measures; access to medical records. |

| Care recipient participation in advance care planning | Determination of care recipient capacity to make health care decisions (ability to state choices, provide reasons, and understand relevant information and consequences); choice of health care proxy; considerations when dementia is present. Encourages resident participation if at all possible. |

| Communication between caregiver, care recipient, and physician | Need to discuss advance directives preferences; resident prognosis; institutional policies potentially conflicting with preferences; resident communication supports (e.g., hearing aids, written/visual supports). |

| 3. Emotional Well-Being (4 Sessions) | Content |

| Baseline assessment | Measure caregiver levels of depression and anxiety. |

| Computer-video and overview/signs of depression and anxiety in caregivers at the institutionalization transition | Educational and informational materials developed to serve as an overview of the salient emotional issues facing caregivers both generally and in relation to placement of a relative are reviewed with caregiver. Handouts on topics are provided. |

| Stress reduction and relaxation | Signal breath and music relaxation are taught to all caregivers. Signal breath teaches a breathing technique that allows caregivers to reduce their stress immediately within a stressful moment using a breathing technique. Music relaxation involves identifying music that is appealing to the caregiver and using it on a regular schedule while keeping a stress diary to document its effect. Stretching and guided imagery will also be offered as additional techniques for caregivers to learn. |

| Managing your mood | A process called The Action-Belief-Consequences Model or the A-B-C Model was used to help caregivers change negative thoughts and beliefs which will in turn improve mood. The technique includes keeping a diary of unhelpful thoughts and exercises to identify the feelings related to the thoughts and ways to replace them with more helpful positive thoughts. |

| Increasing pleasant events | This process helps caregivers recognize the value and emotional benefit of actively including events or activities that the caregiver finds enjoyable to his or her regular routine. The module provides steps to identify pleasant events and plans to successfully include them in the day as well as ways to schedule and monitor the caregiver’s goals in adding pleasant events. |

The intervention was delivered via 11 sessions, lasting approximately 90 minutes each, distributed over a 4 to 6 month period. Nine of the 11 sessions were delivered in the caregivers’ home, and the remaining two were delivered via telephone. All family caregivers began with the Basic Knowledge Module. Modules 2 and 3 were delivered in alternating sessions, based on caregiver need and preference, a strategy successfully used in the REACH intervention trial.

The introduction, overview, and key concepts for each module were delivered via professionally-produced interactive videos presented on a laptop computer brought to the caregivers’ home by the interventionist. Once the introductory materials were presented by computer, the interventionist implemented the remainder of the intervention on a one-on-one interactive basis. For each module the interventionist first assessed the level of knowledge and skills individual caregivers had about a particular domain in order to customize the delivery of the material. For example, if a caregiver was very knowledgeable about nursing home organization and procedures, little time was spent on this component of the intervention.

Interventionists were Masters level social workers and were trained and certified to deliver all components of the intervention. Intervention sessions were audiotaped and monitored for compliance to the treatment protocol. Interventionists were required to complete a “delivery assessment” and “case log” for each intervention contact.

Information Only Control Group

Participants in the control group received a portion of the standardized packet of written information provided to the treatment group. This packet contained several fact sheets from a nationally-recognized expert source in caregiving (the Family Caregiver Alliance’s National Center on Caregiving) and a national information and advocacy group (the National Citizens’ Coalition for Nursing Home Reform). The fact sheets are relevant to the placement of a family member into a nursing home and are linked to the content areas covered in the intervention. Documents in this packet included “Caregiving and Depression,” “End of Life Decision Making,” and “Taking Care of You: Self-Care for Family Caregivers” from the Family Caregiver Alliance; and “Family Involvement in Nursing Home Care,” “Problem Solving,” and “Residents’ Rights” from the National Citizen’s Coalition for Nursing Home Reform. Also provided were a resource guide containing local contact information, such as for the Area Agency on Aging, the local Long-term Care Ombudsman, and local Medicare/Medicaid offices, as well as links to Internet-based consumer, state, federal, and disease-specific websites related to long-term care. This approach has been used successfully with control group participants in the REACH study as well as in the Caregiver Intervention for Caregivers of Spinal Cord Injury Patients study (Belle et al., 2006; Schulz et al., 2009). No training or other interventionist engagement were provided, other than two “check-in” phone contacts at the end of months 2 and 4. Any unscheduled contacts initiated by the caregivers in the control condition were recorded as to reason why, type, and duration of contact, and disposition.

Measures

The primary outcome measures for the study were depression, state anxiety, caregiver burden, and complicated grief for those caregivers whose care recipient died during the course of the study. Each of these measures is described below.

Depression

The 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977; Irwin, Artin, & Oxman, 1999) was used to assess depression in both caregivers and care recipients. Using the previous week as a reference, respondents rated each item on a scale from 0 (experienced rarely or none of the time) to 3 (experienced most or all of the time). Scores range from 0 through 30, with higher scores indicating increased presence of depressive symptoms; a score of 8 or higher (equivalent to 16 or higher on the 20-item scale) is widely interpreted as being at risk for clinical depression (Irwin et al., 1999; Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). Cronbach’s alpha at baseline was .87.

Anxiety

State anxiety was measured using 10 items from the Spielberger and colleagues (1983) State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed (not at all, somewhat, moderately, very much) with 10 statements characterizing how they felt during the past week (I felt calm, I was tense, I felt nervous, etc.). Scores range from 0 to 30 with high scores indicating high levels of anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha at baseline was .91.

Caregiver Burden

The brief (11 items, 1 item of the 12-item scale was dropped because it was not relevant to the nursing home context) version of the Caregiver Burden Interview (Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985; Bedard et al., 2001) was used to assess burden. Each item was rated on a 5 point scale from 0 (never) through 4 (nearly always), yielding a possible range of 0 to 44. Higher values indicate greater levels of caregiver burden. Cronbach’s alpha at baseline was .85.

Complicated Grief

For those caregivers whose resident died in the course of the study, the Complicated Grief Scale (Prigerson et al., 1995) was administered at each measurement point post-death. For each of the 19 statements (e.g., I feel I cannot accept the death of…”), caregivers were asked to report whether they currently felt this way: never (0); rarely (1); sometimes (2); often (3); or always (4) (possible range: 0–76, high values indicating high levels of complicated grief). Scores of 25 and higher have been recommended as cutoffs for designating individuals with complicated grief (Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

In addition to the primary outcomes listed above, we also administered three instruments designed to assess the caregiver’s perception of the quality of care provided by the nursing home, their satisfaction with care provided, and whether or not they had problems with the nursing home. Perceived quality of care was measured with 3 items assessing how often the care recipient’s (CR) personal care needs, such as bathing and dressing, were taken care of as well as they should have been, how often CR was treated with respect by those who were taking care of him/her, and how often CR was treated with kindness by those taking care of him/her. For each question the response options were never (0), sometimes (1), usually (2), and always (3). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .76. Satisfaction with care provided was captured with 3 items assessing satisfaction with the social environment, physical environment, and the quality of care provided to the CR. Each item included response options of not at all satisfied (1), just a little satisfied (2), fairly satisfied (3), and very satisfied (4). Cronbachs alpha for this scale was .79. A 14-item scale measuring problems with the nursing home (e.g., financial issues you didn’t expect, feeling the staff doesn’t like when you ask questions, worrying about CR’s safety, finding people in charge who were willing to discuss your concerns, etc.) was also administered. For each item the caregiver responded never (0), once in a while (1), fairly often (2), and very often (3). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .85.

To assess CR’s functional status, we administered a 7-item activities of daily living (ADL) scale, asking caregivers to indicate whether or not the CR needed help with each ADL (Belle et al., 2006; Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963; Lawton & Brody, 1969). Perceived quality of life of the CR was assessed with a 15-item scale rating the CR on dimensions such as physical health, energy, mood, memory, ability to keep busy, ability to do things for fun, ability to make choices in one’s life, etc. (Winzelberg, Williams, Preisser, Zimmerman, & Sloane, 2005). For each item the caregiver rated the CR as poor (0), fair (1), good (2), or excellent (3). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .83.

Finally, because one of the components of the intervention focused on advanced care planning, we administered an 8-item scale from the measurement toolkit developed by Teno et al. (Teno, Clarridge, Casey, Edgman-Levitan, & Fowler, 2001). Using yes-no response options, caregivers were asked, e.g., whether the CR was involved in making advance care planning decisions, whether a relative was appointed as their healthcare surrogate, whether the CR had a living will, and whether CR knew about and discussed do-not-resuscitate order with the physician.

Statistical Analysis

We first examined baseline differences between treatment and control conditions on all primary and secondary outcome measures. Chi-square tests of association were employed for dichotomous outcomes while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for continuous outcomes. Because many of these outcomes were based on sums obtained from ordinal scales, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were also assessed (results not shown).

The analysis of primary and secondary outcomes as related to time and treatment was conducted with GEE analyses (Liang & Zeger, 1986). Results are given based on the 6, 12, and 18 month follow-up periods. We used all available data at each measurement point for the analysis. Missing data was minimal (e.g., at 6 months, 6 of 106 observations in the Control Arm and 7 of 107 observations in the Intervention Arm). The independent variables for GEE analysis were group assignment, time, and the interaction of group by time. Since there were two outcomes detected to be at least marginally different between treatment and control conditions at baseline using both parametric and non-parametric methods (caregiver burden and care recipient’s quality of life), they were included as adjustment factors in the GEE models. The adjusted models are reported in this paper, but the results are same for the unadjusted models. In addition, the specific long-term care facility was adjusted for. Note that for the primary outcome measure of burden, sample sizes are reduced because this measure could not be administered to caregivers whose resident died prior to assessment. Conversely, measures of complicated grief could only be administered to caregivers of placed residents who died in the course of the study. For the latter sub-sample we assessed group differences in complicated grief using GEE.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

Caregivers were predominantly White women with a median age of 60 who were either spouses (26%) or adult children/others (74%) of the placed care recipient (see Table 2). Placed care recipients were also predominantly White females with a mean age of 82.8 and a median number of limitations in 7 of 7 Basic ADLs (Katz et al., 1963; Lawton & Brody, 1969).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics | All (N=217 ) | Control (n=108) | Treatment (n=109) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Caregiver, Mean (s.d.) | 61.8 (10.78) | 61.1 (9.93) | 62.5 (11.56) | .33 |

| Age of Care Recipient, Mean (s.d.) | 82.8 (9.23) | 83.3 (9.84) | 82.4 (8.62) | .49 |

| Gender of Caregiver, Women, No. (%) | 163 (75.1) | 81 (75.0) | 82 (75.2) | .97 |

| Gender of Care Recipient, Women, No. (%) | 136 (62.7) | 64 (59.3) | 72 (66.1) | .30 |

| Race of Caregiver | ||||

| Non-African-American, No. (%) | 195 (89.9) | 95 (88.0) | 100 (91.7) | .36 |

| African-American, No. (%) | 22 (10.1) | 13 (12.0) | 9 (8.3) | |

| Spousal Relationship | ||||

| Spouse, No. (%) | 57 (26.3) | 24 (22.2) | 33 (30.3) | .18 |

| Child/Other, No. (%) | 160 (73.7) | 84 (77.8) | 76 (69.7) | |

| Depression Scoreb, Mean (s.d.) | 9.5 (7.26) | 9.3 (7.60) | 9.7 (6.92) | .63 |

| Anxietyc, Mean (s.d.) | 12.5 (7.35) | 11.9 (7.59) | 13.2 (7.09) | .22 |

| Burdend, Mean (s.d.) | 15.3 (8.59) | 14.3 (8.72) | 16.4 (8.36) | .08 |

| Satisfaction with LTCe, Mean (s.d.) | 9.5 (2.02) | 9.8 (1.82) | 9.3 (2.18) | .07 |

| Problems with LTCf, Mean (s.d.) | 20.2 (6.16) | 20.1 (6.20) | 20.4 (6.14) | .70 |

| Quality of LTC g, Mean (s.d.) | 10.1 (1.69) | 10.3 (1.57) | 9.9 (1.79) | .16 |

| Quality of Care Recipient’s Life h, Mean (s.d.) | 27.6 (6.64) | 28.5 (7.03) | 26.7 (6.14) | .04 |

| Advance Care Planning i, Mean (s.d.) | 13.3 (2.09) | 13.3 (2.17) | 13.4 (2.01) | .66 |

| Sum of ADL’s j, Mean (s.d.) | 5.8 (1.88) | 5.8 (1.71) | 5.8 (2.04) | .97 |

Abbreviations: s.d. - standard deviation; LTC - long-term care facility; ADL - activities of daily living.

P values are based on two group comparisons; Pearson χ2 test for dichotomous outcomes (presented by number [%]) and One-way ANOVA tests for continuous outcomes (presented by mean and standard deviation).

Depression scores are based upon the CES-D scale (range, 0–30; higher scores indicate more reported depression).

Anxiety scores are based on the State Anxiety Inventory (range, 0–30; higher scores indicate more reported anxiety).

Caregiver burden scores (range, 0–42; higher scores indicate more reported burden).

Satisfaction with the LTC is based on a summary of scores on an ordinal scale (range, 3–12; higher scores indicate higher satisfaction).

Problems with the LTC are a summary of scores on 14 various questions (range, 14–43; higher scores indicate more reported problems).

Quality of the LTC is based on a summary of 3 questions on an ordinal scale (range, 6–12; higher scores indicate higher reported quality).

The Quality of Life of the Care Recipient as reported by the Caregiver responses to 15 questions (range, 14–46; higher scores indicate higher quality of life).

Advanced Care Planning is based upon 8 dichotomous questions (range, 8–16; higher scores indicate higher levels of advanced care planning).

Any reported problems with 7 activities of daily living (ADL) are counted and summed (range, 0–7; higher scores indicate more ADL problems).

Baseline Comparisons between Treatment and Control Group

Baseline values for caregivers assigned to treatment and control conditions on all outcome measures are presented in Table 2. No differences in treatment and control groups were found for any of the demographic measures. There was a significant difference in quality of life of the care recipient (p = 0.04) and marginally significant differences in caregiver burden (p = 0.08) and satisfaction with LTC (long-term care) (p = 0.07) using ANOVA. When the Mann-Whitney U test was employed, results for these outcomes were somewhat different; quality of life of the care recipient (p = 0.04) and caregiver burden (p = 0.03) were significantly different, but satisfaction with LTC (p = 0.15) was not. The direction of the differences was that the treatment group reported lower levels of quality of life for the care recipients, higher levels of caregiver burden, and less satisfaction with LTC.

Treatment Effects

Using baseline and 6-month follow-up data, we tested for group effects, time effects, and group by time interactions. No statistically significant group effects were found. Several significant time effects were found, indicating that caregiver depression [mean change −1.02; 95% CI (−1.85, −0.20)], anxiety [−2.05; 95% CI (−3.00, −1.10)], and burden [−2.75; 95% CI (−3.74, −1.77)] decreased over time regardless of group assignment. In addition, caregivers reported higher quality of life [+1.25; 95% CI (+0.43, +2.06)] of the care recipients over time and were more likely to engage in advanced care planning [+0.66; 95% CI (+0.35, +0.97)] over time. None of the group by time interactions were statistically significant, indicating that there were no differences between treatment and control groups t the 6-month follow-up assessment.

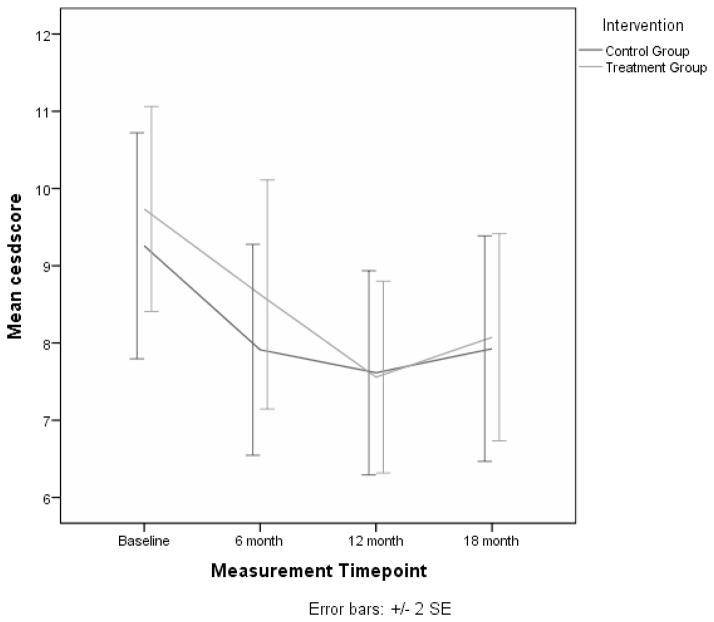

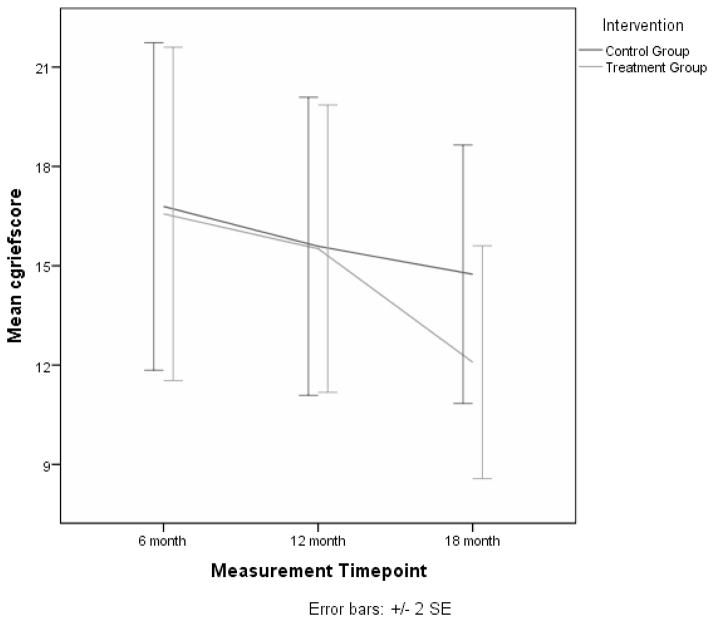

Analyses were carried out for each of these outcomes using all available follow-up assessments at 6, 12, and 18 months.. Compared to baseline values, caregiver depression was significantly lower at 6 (p = 0.03) and 12 months (p = 0.03), but not at 18 months (see Figure 1). Anxiety was lower at all 3 follow-up time periods (6 months, p = 0.02; 12 months, p < 0.01; 18 months, p = 0.02). Caregiver burden was also significantly lower at each of the follow-up time points (6 months, p < 0.01; 12 months, p < 0.01; 18 months, p < 0.01). None of the group by time interactions for these outcomes were significant at any of the follow-up assessments (see Table 3). However, a significant interaction effect was found for complicated grief at the 18 month time point (p = 0.01). This is illustrated in Figure 2 where it is shown that the treatment group had lower average scores for complicated grief when compared to controls. In addition, the quality of the care recipient’s life, as reported by the caregiver, showed a significant interaction effect at the 12 month time point (p < 0.01), indicating that perceived quality of life of the care recipient in the treatment group was higher at 12 months than the control group. Finally, advance care planning increased at each follow-up time point (6 months, p = 0.01; 12 months, p < 0.01; 18 months, p < 0.01), but no significant interaction effects were found for this variable.

Figure 1.

Mean Depressive Symptom Scores for Treatment and Control Groups over Four Measurement Points.

Table 3.

Analysis of Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures – Group by Time Interaction Effects

| Group by Time Interactions

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group by 6 Months | Group by 12 Months | Group by 18 Months | ||||

| Est (Std Error) | p | Est (Std Error) | p | Est (Std Error) | p | |

|

| ||||||

| Primary Outcomes | ||||||

| Depression Score (N = ) | 0.34 (0.84) | .68 | −0.66 (0.82) | .42 | −0.57 (0.97) | .56 |

| Anxiety | −0.96 (0.96) | .32 | −1.66 (0.93) | .08 | −1.37 (1.01) | .17 |

| Caregiver Burden | −0.85 (0.97) | .38 | −1.48 (1.15) | .20 | −0.55 (1.23) | .65 |

| Complicated Griefc | - | - | −0.44 (1.92) | .82 | −4.74 (1.90) | .01* |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||

| Satisfaction with LTC | +0.43 (0.32) | .18 | +0.45 (0.34) | .18 | +0.31 (0.33) | .35 |

| Problems with LTC | +0.89 (0.76) | .24 | +0.01 (0.97) | 1.00 | −0.19 (1.08) | .86 |

| Quality of LTC | +0.18 (0.23) | .43 | +0.14 (0.26) | .58 | −0.03 (0.25) | .92 |

| Advance Care Planning | +0.07 (0.30) | .82 | +0.16 (0.34) | .65 | 0.27 (0.37) | .47 |

| QoL of Care Recipient | +0.11 (0.79) | .89 | +3.36 (0.91) | <.01* | +1.71 (1.09) | .12 |

Abbreviations: Est - parameter estimate; Std Error - standard error of parameter estimate; QoL – quality of life.

Sample sizes are based on the 18 month follow-up period.

Statistically significant interaction effects

Figure 2.

Mean Complicated Grief Scores for Treatment and Control Groups over Four Measurement Points.

Treatment Exposure Effects on Outcomes

The total amount of contact time (in minutes) during the intervention period was examined with regard to the primary outcomes. Using GEE models with total contact time as a main effect, no significant results were obtained. The estimates and associated p-values were (+0.000; 0.91) for depression, (+0.001; 0.67) for anxiety, (+0.000; 0.90) for caregiver burden, and (+0.005; 0.16) for complicated grief.

DISCUSSION

The current study was designed to assess the efficacy of an intervention specifically aimed at addressing 3 needs of caregivers who recently institutionalized their care recipient – emotional distress, knowledge about the long-term care procedures and resident trajectories, and end-of-life care planning. This trial is unique in this area in adhering to strict randomized controlled trial procedures, specifically targeting specialized needs of caregivers of institutionalized residents, assessing outcome in both the short- and long-term, and evaluating bereavement effects in the context of caring for an institutionalized resident.

We found that the intervention had no effect on the primary outcomes of depression, anxiety, or burden. Significant treatment effects were found for one primary outcome, complicated grief, showing that caregivers in the treatment condition had lower levels of complicated grief after their relative died.

The lack of significant effects on most outcomes begs the question, what might account for these null findings? Although explaining null effects is a risky proposition, it may nevertheless be useful to speculate about possible reasons for our findings. Caregivers in both treatment and control groups significantly improved on most outcome measures over time. This could be due to the fact that caregivers normatively adapt to the placement of their relative, or alternatively, that even minimal support provided to caregivers is beneficial. Since our control condition provided caregivers with written information in each of the areas of the intervention, it is possible that this minimal intervention combined with the attention they received as part of the assessment process contributed to improvement in caregivers over time. That said, it should be noted that mean levels of CESD symptoms did not go below 7.5 (equivalent of 15 on full scale) at any measurement point, a value that places caregivers near the cut point for being at risk for clinical depression (CESD = 16 or higher). The fact that similar values are reported by Schulz et al. (Schulz et al., 2004) for a sample of caregivers of placed dementia patients suggests that our findings reflect normative adaptation to placement, and that additional gains might still be achieved with an effective treatment. In other words, there is room for improvement in both intervention strategies and caregiver outcomes.

How might the intervention be improved? One strategy would be to introduce the intervention earlier in the placement transition process. Our intervention was designed to benefit individuals who recently placed their relative at a time when their knowledge of and experience with long-term care settings was limited. In practice, this proved to be difficult to do because placement is a complex transition that typically involves multiple alternating episodes of hospitalization, placement in long-term care facilities for rehabilitation, and home care. As a result, by the time a resident is permanently placed in a skilled nursing facility, both family members and residents may already have extensive prior experience with long-term care facilities. This would diminish the value of what we had to offer through our intervention. A more effective strategy might be to develop interventions that specifically target the transition experience and recruit caregivers prior to placement. This would require identifying high risk in-home caregivers and following them through the transition period to permanent placement.

Another strategy for enhancing intervention efficacy might be expanding the focus of treatment to include both caregivers and nursing home personnel. For example, if the goal is to foster advance care planning, complementary strategies that educate caregivers about the importance and value of advance care planning and training staff on how to facilitate this process would likely be more effective than targeting only caregivers. This is the strategy adopted by Pillemer et al. (Pillemer et al., 1998; Pillemer et al., 2003) to improve communication between caregivers and staff but has not been implemented with the type of intervention used in this study.

The intervention was successful in mitigating the negative effects of death on the caregiver. Caregivers in the treatment condition were less likely to experience complicated grief post-bereavement when compared to caregivers in the control condition. We reasoned that the intervention would sensitize caregivers to the likelihood of death and through activities such as advanced care planning would better prepare them for death. Our findings support this conclusion and are consistent with other data showing that interventions delivered during active caregiving may benefit caregivers post-bereavement (Schulz, Boerner, Shear, Zhang, & Gitlin, 2006).

Our findings have several implications for clinical practice. Although we show that there is considerable spontaneous caregiver adaptation to placement and ultimately death of the care recipient, there is also room for improvement that could be facilitated by clinical intervention. Educating caregivers about long-term care facilities and their operation, helping them with advance care planning for the patient, and providing them with skills to manage their own well-being may accelerate the adaptation process, particularly if delivered early in the transition to long-term care. Importantly, getting caregivers to engage in these activities is protective of adverse bereavement outcomes. Clinicians can also play an important role in monitoring caregiver adaption over time to identify caregivers who do not exhibit spontaneous recovery in their well-being after their relative is placed. They should be targets of intensive intervention and would likely benefit from existing clinical treatment strategies for depression such as cognitive behavior therapy.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NR009573).

Contributor Information

RICHARD SCHULZ, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

JULES ROSEN, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

JULIE KLINGER, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

DONALD MUSA, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

NICHOLAS G. CASTLE, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

APRIL KANE, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

AMY LUSTIG, Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M, Molloy W, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit burden interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, Gitlin LN, Klinger J, Koepke KM, Lee CC, Martindale-Adams J, Nichols L, Schulz R, Stahl S, Stevens A, Winter L, Zhang S Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health REACH II Investigators. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: a randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(10):727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Nolan M. ‘Making the move’: Relatives’ experiences of the transition to a care home. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2004;12(6):517–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JD, Tremont G, Bishop DS, Fortinsky RH. A telephone-delivered psychosocial intervention improves dementia caregiver adjustment following nursing home placement. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;26(4):380–387. doi: 10.1002/gps.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann ML, Montgomery RJ, Maiberger B, Smith AA. Family involvement in the nursing home: Family-oriented practices and staff-family relationships. Research in Nursing and Health. 1997;20(6):527–537. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE. Staff perceptions of residents across the long-term care landscape. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49(4):377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Anderson KA, Zarit SH, Pearlin LI. Family involvement in nursing homes: effects on stress and well-being. Aging and Mental Health. 2004;8(1):65–75. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001613356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S.: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2007;7(13) doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Holmes HH. Families’ experiences of long-term care placement: Adaptation and intervention. Clinical Psychologist. 2003;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.1080/13284200410001707463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Roth DL, Haley WE, Mittelman MS. Can counseling and support reduce Alzheimer’s caregivers’ burden and depressive symptoms during the transition to institutionalization? Results from the NYU caregiver intervention study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;53(3):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Lopez RP, Mazor KM, Mitchell SL. Sources of stress for family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2012;26(3):254–259. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31823899e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Prigerson HG, Jones RN, Mitchell SL. Mental health and exposure to patient distress among families of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;42(2):183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.10.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski DC, Mitchell SL. Family oversight and the quality of nursing home care for residents with advanced dementia. Medical Care. 2009;47(5):568–574. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195fce7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159(15):1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan L, Boss P. Depressive symptoms among spousal caregivers of institutionalized mates with Alzheimer’s: Boundary ambiguity and mastery as predictors. Family Process. 1999;38(1):85–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe J, Fancey P. The care continues: Responsibility for elderly relatives before and after admission to a long-term care facility. Family Relations. 2000;49(3):235–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00235.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lindman Port C. Identifying changeable barriers to family involvement in the nursing home for cognitively impaired residents. The Gerontologist. 2004;44(6):770–778. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.6.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallion P, Toseland RW, Freeman K. An evaluation of a family visit education program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47(2):203–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Kosloski K. A longitudinal analysis of nursing home placement for dependent elders cared for by spouses vs. adult children. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49(2):S62–74. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Hegeman CR, Albright B, Henderson C. Building bridges between families and nursing home staff: the Partners in Caregiving Program. The Gerontologist. 1998;38(4):499–503. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Henderson CR, Jr, Meador R, Schultz L, Robison J, Hegeman C. A cooperative communication intervention for nursing home staff and family members of residents. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(Spec No 2):96–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, III, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, Frank E, Doman J, Miller M. The inventory of complicated grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research. 1995;59(1–2):65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robison J, Curry L, Gruman C, Porter M, Henderson CH, Jr, Pillemer K. Partners in caregiving in a special care environment: Cooperative communication between staff and families on dementia units. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):504–515. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AA, Scullion HF. Family and staff perceptions of the role of families in nursing homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;32(3):626–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, McGinnis KA, Stevens A, Zhang S. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292(8):961–967. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, Zhang S, Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: A prospective study of bereavement. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):650–658. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203178.44894.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Boerner K, Hebert RS. Caregiving and bereavement. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W, editors. Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: 21st Century Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2008. pp. 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Czaja SJ, Lustig A, Zdaniuk B, Martire LM, Perdomo D. Improving the quality of life of caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: A randomized controlled Trial. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54(1):1–15. doi: 10.1037/a0014932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF. Treatment of complicated grief. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, Edgman-Levitan S, Fowler J. Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2001;22(3):752–758. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatore JB, Grant LA. Burden among family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(4):497–506. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatore JB, Grant LA. Family caregiver satisfaction with the nursing home after placement of a relative with dementia. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59(2):S80–88. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Schur D, Noelker LS, Ejaz FK, Looman WJ. The stress process of family caregiving in institutional settings. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(4):462–473. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SW, Zimmerman S, Williams CS. Family caregiver involvement for long-term care residents at the end of life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67(5):595–604. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzelberg GS, Williams CS, Preisser JS, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD. Factors associated with nursing assistant quality-of-life ratings for residents with dementia in long-term care facilities. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(Special Issue 1):106–114. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Mitani N, Aneshensel CS, Levy-Storms L. Patterns of family visiting with institutionalized elders: The case of dementia. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(4):S234–246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.S234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Orr NK, Zarit JM. Families under stress: Caring for the patient with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. New York: University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Institutional placement: Phase of the transition. The Gerontologist. 1992;32(5):665–672. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]