Abstract

During electrocochleography, that is, ECochG or ECoG, a recording electrode can be placed in the ear canal lateral to the tympanic membrane. We designed a concha electrode to record both sinusoidal waveforms of cochlear microphonics (CMs) and auditory brainstem responses (ABRs). The amplitudes of CM waveforms and Wave I or compound action potentials (CAPs) recorded at the concha were greater than those recorded at the mastoid but slightly lower than those recorded at the ear canal. Wave V amplitudes recorded at the concha were greater than those recorded at the ear canal but lower than those recorded at the mastoid. There was not a significant difference between the amplitudes recorded at the concha and at the ear canal. For CM and Wave I or CAP, the latency recorded at the concha was longer than at the canal but shorter than at the mastoid; for Wave V, the reverse was true. However, these differences were not statistically significant and may be due to the distance to response generators. Aside from the advantages that the regular ECoG has over otoacoustic emission (OAE) testing, the concha electrode was also easier and safer to place and may be suitable for children, newborn screening, participants with canal conditions, and remote clinics which could have concerns with the availability and cost of a canal electrode. Using concha electrodes, we also experienced fewer postauricular artifacts than when using a mastoid electrode.

Keywords: concha electrode, ear canal electrode, electrocochleography (ECoG or ECochG), cochlear microphonics (CMs), auditory brainstem responses (ABRs)

Introduction

We present our report on a study of cochlear microphonic (CM) sinusoidal waveforms and auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) measured with a concha electrode (an electrode placed at the concha). The responses measured were compared with those measured with a canal electrode (an electrode placed in the external ear canal) and a mastoid electrode (an electrode placed on the mastoid). As the concha adjoins the canal, we would expect them to share a very similar electrical expression; therefore, we hypothesized that the electrical responses recorded at these two locations would be very similar. If this is true, the concha electrode may become a very useful alternative to a canal electrode.

As an initial step, we explored the feasibility of using a concha electrode by testing with one frequency and one level in a stimulus paradigm. We selected a low frequency and a high suprathreshold level because our previous work with the canal electrode showed that this paradigm could induce a robust response (Zhang, Davis, et al., 2007). For example, the use of a low-frequency stimulus elicits smaller ABRs so that superposition of ABRs on CMs is minimized, thereby reducing variability.

Need for Simultaneous Measurement of Both ABR and CM Responses

The measurement of both CMs and ABRs is important in the assessment of hearing and hearing loss (Attias, Nageris, Ralph, Vajda, & Rappaport, 2008; Ciorba et al., 2009; Ohashi et al., 1996; Rosahl, Tatagiba, Gharabaghi, Matthies, & Samii, 2000). ABRs represent the status of the neural components (Miller, Brown, Abbas, & Chi, 2008; Montaguti, Bergonzoni, Zanetti, & Rinaldi Ceroni, 2007), whereas the CMs represent the status of the cochlear functions as they basically arise from the hair cells (Dallos, 1973; Eggermont, 1976; Ferraro & Durrant, 2002). In some disorders, the two types of responses are not correlated, so one type of response cannot be used to predict the other (Shehata-Dieler, Volter, Hildmann, Hildmann, & Helms, 2007). For example, in auditory neuropathy, the disappearance of ABRs does not predict an abnormal status of the cochlea (Shehata-Dieler et al., 2007; Zeng & Liu, 2006).

Limitations Associated With Setting of Otoacoustic Emission (OAE) Testing

Both CMs and OAEs may be used to assess cochlear functions as the CMs and OAEs are elicited from the same generator involving the hair cells (Norton, Ferguson, & Mascher, 1989). However, in the clinic, at low frequencies (e.g., 500 Hz), OAE is difficult to measure due to background noise, breathing, and cardiovascular murmurs (Tognola, Ravazzani, & Grandori, 1995) and at high levels, this metric is vulnerable to artifact. The TEOAE cannot exceed typically ∼5-kHz limit whereas the DPOAE (2f1-f2) cannot pinpoint to one individual frequency. The setting of the OAE recording cannot be used to measure neural response such as ABRs. From these, it is clear that the OAE testing has at least these four limitations whereas the CM testing does not (Zhang & Abbas, 1997). In addition, CM measurement is reliable (Zhang & Raju, 2009). Simultaneous recording of cochlear and neural responses by using one setting instead of two settings is also cost effective and time efficient.

Consideration and Initiation of the Study on the Concha Electrode

The location of the electrode is critical when measuring CMs. Therefore, the placement of electrodes at several locations has been studied. It is acknowledged that Wever and Bray first recorded the CM but they claimed it to be a neural response (Wever & Bray, 1930). Later, Adrian suggested that the CM originated in the cochlea (Adrian, 1931). Additional details are provided in Dallos' book (Dallos, 1973). In the past 80 years, with the advancement of technology, the electrode location for CM measurement has migrated outward from inside the cochlea, to outside cochlea, the round window niche or promontory area, outside the middle ear, the tympanic membrane, and eventually the external ear canal (Ferraro & Durrant, 2002). Typically, the term electrocochleography was used, which includes the CM measurement. Using this extensive location data, we considered the concha as the next location, which is lateral to the ear canal but with almost no distance between. We have initiated the exploration of the possibility to use the concha electrode, and portions of this work have been presented (Zhang, King, & Flores, 2007).

Relevant Questions

We have conducted this study in an attempt to address some of the following questions. Can we compromise between the mastoid and ear canal electrode by placing the electrode at a new location? Where is the best location for placement? What types of responses can be recorded from the new location? What will the responses appear like? Can the new location be used in a clinical setting? What will be the pros and cons if the new location is attempted? Can the concha be a new alternative location for a recording electrode?

Method

Participants

A total of 10 human participants ranging in age from 20 to 30 were recruited. All 10 participants were recruited as one group. Nine were female and one was male. They were native English speakers, healthy, and reported no hearing problems for the past 5 years. Otoscopy and tympanometry were conducted to exclude abnormality in the external and middle ear. Audiometric measurements were conducted in a sound-treated double-walled booth to determine the eligibility for participation. Criteria for participation included having normal hearing sensitivity at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz at ≤20 dB HL in both ears and no significant air-bone gap (≤10 dB HL difference between air and bone conduction thresholds at any audiometric test frequency).

Stimuli

The stimuli were created using the parameters set by the software program Bio-logic Navigator Pro Auditory Evoked Potential System (Natus Medical Incorporated, San Carlos, CA). The stimulation system and intensity were calibrated in accordance with ANSI standards, 1996. Two types of stimuli were formulated. One was a 0.1-ms click at 80 dB nHL for the measurement of the ABRs and the other was a tone-burst for measurement of CMs. The toneburst was relatively long (14 ms) gated with a 4-ms rise-fall time. Setting a longer rise-fall time minimized the possibility of evoking prominent waves of ABRs. A CM waveform relatively immune from ABR waveforms would make data analysis simpler and more accurate.

Recording

Recording was conducted similar to those as previously reported (Ferraro, Nunes, & Arenberg, 1989; Gouveris & Mann, 2009; Zhang & Abbas, 1997; Zhang, King, et al., 2007; Zollner & Karnahl, 1975): 30 to 2,000 Hz filter for real time ABR recording and 50 to 2,000 Hz for CMs, 100,000x gain, artifact rejection feature on, 27.7/s rate to minimize 60-Hz artifacts, 2,000 sweeps, 10- to 20-ms epoch, correction of 0.8-ms acoustic delay, and sampling rate much higher than the Nyquist frequency to avoid sampling alias. The recording electrode (inverting or “-” electrode) was placed at the ipsilateral side (ear canal, concha, or mastoid); the reference (noninverting or “+” electrode) at forehead; the common (ground or “G” electrode) on the contralateral side.

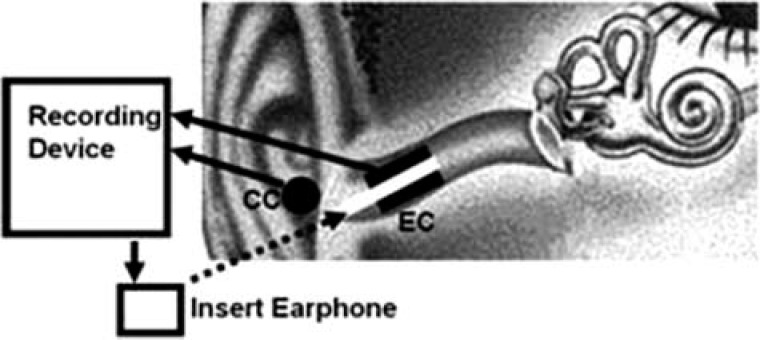

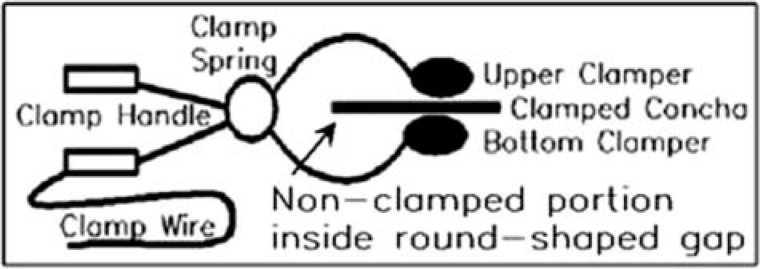

For the placement of recording electrodes, the mastoid electrode was a surface disc electrode placed on the mastoid prominence; the canal electrode was a plug wrapped with gold foil and inserted in the canal (Figure 1); the concha electrode was a customized electrode and clamped at the concha (Figure 2). The clamp wire led the collected responses to the recording amplifier. Pressing the clamp handle opened the two clampers (upper and bottom), and releasing the handle clamped the concha after placing the two clampers on the front and back side of the concha respectively, as shown in Figure 2. Pressure applied to the clamp decreased the impedance of the recording electrode. The electrode design also assured that there was adequate space so that no contact existed between the clamp and other pinna structures such as the helix, antihelix, or the antitragus. As such, the concha electrode possesses adequate clamping force and is easier to place than the mastoid electrode, which requires glue- or tape-force to anchor.

Figure 1.

Measurement setting

Note: Driven by the stimulus current from the recording device (an interface box and a PC), the inserted ear phone delivered the acoustic stimuli to the ear canal (EC) via a sound delivery tube and earplug. The responses collected by the recording electrodes at the EC or concha (CC) were relayed to the recording device. The concha adjoins the EC. 26 × 11 mm (300 × 300 DPI).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the concha clamp electrode and its placement method

Note: A round or oval-shaped gap between the upper and bottom clampers provided room for the nonclamped portion of the pinna (i.e., helix, antihelix, and antitragus). 29 × 10 mm (300 × 300 DPI).

Data Analysis

Data were collected from recording electrodes at three locations: ear canal, concha, and mastoid, so comparisons were made among these three data groups. For each location, both ABRs and CM sinusoidal waveforms were recorded; so six data sets were generated. Each set of data was deemed to serve as a test group in one analysis and as a control group in the other analysis. For example, when we focused on concha electrode, the data collected with concha electrode were referred to as a test group; the amplitude of the Wave I and CM sinusoidal waveforms recorded at the concha location was compared with those recorded at the ear canal and mastoid prominence.

For the ABR data, Waves I and V were identified. The latencies were measured from the stimulus onset to the peak of the waves. The amplitudes were measured from peak to subsequent trough. The amplitude of the CMs was obtained over an average of two or three of five sinusoidal waveforms recorded during the 10-ms plateau period (Zhang, Davis, et al., 2007). As 20 ears were tested, data were pooled for the statistical analysis. The means and differences among groups were analyzed and compared statistically with ANOVA methods. The significance was considered at p < .05.

Results

Auditory Brainstem Responses

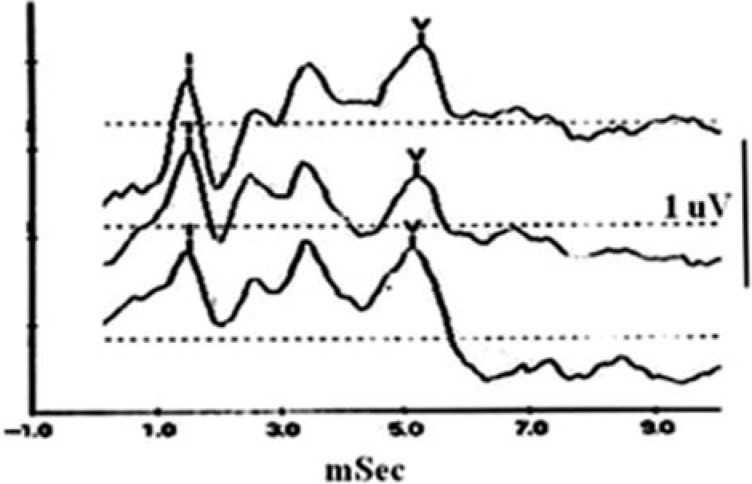

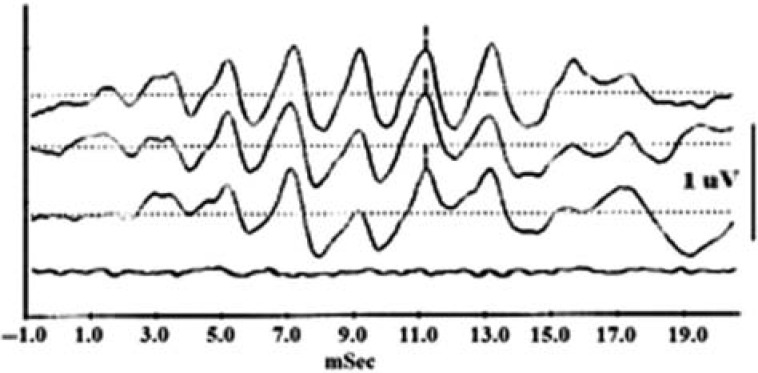

Figure 3 shows the typical ABRs recorded through the recording electrode placed at three locations: canal, concha, and mastoid. The stimulus was a click. All waves of the responses were clearly displayed, particularly in the Wave I and Wave V, which are the major response waves that are of interest in clinics. The amplitudes and latencies of the three responses recorded from different locations appear similar but are not exactly identical.

Figure 3.

Waveforms of ABRs recorded at the ear canal (top trace), concha (middle), and mastoid (bottom)

Note: I = Wave I; V = Wave V; Vertical line = 1 μV. 24 × 16 mm (300 × 300 DPI).

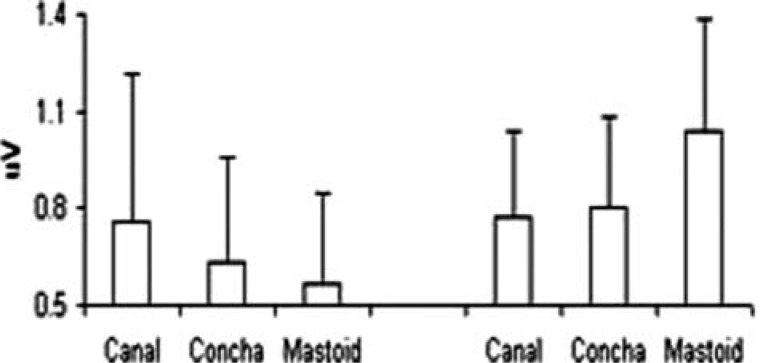

Figure 4 shows the mean amplitudes and standard deviation of the Waves I and V recorded with the recording electrode at the canal, concha, and the mastoid. When compared as in sets of data at each location, the difference was not significant (p > .05) in Wave I and Wave V amplitudes between the responses recorded at the concha and ear canal. However, a significant difference existed between data sets from responses recorded at the concha and mastoid, and between responses recorded at the canal and mastoid. The interamplitude ratio (Wave V/Wave I) was also compared. The difference in ratio was not significant between the responses recorded at the concha and ear canal, but the interamplitude ratio was significantly different for mastoid responses when compared with those recorded at the concha or canal.

Figure 4.

Amplitudes (M and SD) of Wave I or CAP (left three bars) and Wave V (right three bars) recorded at three locations

Note: 25 × 14 mm (300 × 300 DPI).

We also compared the mean latencies for Wave I recorded with the recording electrode placed at the concha, canal, and mastoid. They were 1.53, 1.51, and 1.54 ms, respectively, but the differences are not significant (p > .05). For Wave V, the mean latencies were 5.49 (canal), 5.45 (concha), and 5.42 ms (mastoid), but there were no significant differences (p > .05). The means of interwave interval between Wave I and Wave V was calculated, and they were 3.96, 3.94, and 3.88 ms, respectively, and again the differences were not significant among various placements of recording electrodes (p > .05).

In addition, the number of cases containing postauricular-muscle artifacts were documented and found to be 0 for canal, 1 for concha, and 5 for mastoid placements, which rendered the percentages as 0, 5, and 25, respectively. This information indicated statistical significance between mastoid and concha/canal but not between canal and concha placements.

Cochlear Microphonics

Figure 5 shows CM waveforms to a 500-Hz toneburst stimulation recorded with recording electrodes placed at different locations: canal (the top or 1st waveform in Figure 5), concha (the 2nd waveform), and mastoid (the 3rd waveform). The bottom trace in Figure 5 was recorded with the sound-delivery tube clamped.

Figure 5.

CM sinusoidal waveforms in response to a 14-ms toneburst recorded from different locations: ear canal (1st or top trace), concha bowl (2nd trace), and mastoid (3rd trace)

Note: The CM disappeared when sound delivery tube was clamped (4th or bottom trace). 25 × 12 mm (300 × 300 DPI).

When conducting CM measurement, several key steps were employed to ensure that the responses were not contaminated by electromagnetic interference from the path of stimulation components such as the wire and earphone. The entire wire and earphone were shielded inside a grounded shielding-tube and box, respectively. The shielding material was a MuShield product (The MuShield Company, Manchester, NH). A negative control was performed by clamping the sound-delivery tube to block the delivery of acoustic stimulation to the ear while the earphone coil was still driven by the stimulation current. With the clamp applied, no sound could reach the ear, no response should be evoked, and so no CM sinusoidal waveforms were recorded (Figure 5, the bottom trace). The recorded trace is a flat line without sinusoidal waveforms. The recorded responses were also monitored and inspected to ensure there was latency before the CM waveforms appeared. Electromagnetic interference does not have latency while true responses do, and the responses we recorded did have evidence of latency. Using these steps or criteria, we confirmed that the recorded waveforms were true responses, not merely electromagnetic interference.

The amplitudes and latencies of the three location responses are different. The means of the amplitudes were 0.68 (canal), 0.65 (concha), and 0.60 mV (mastoid). Statistical significances (p < .05) were obtained among the various recording-electrode placements, with the exception of the comparison between concha and canal electrode placements. In other words, the CM recorded from the mastoid is smaller than that recorded from either the canal or the concha. For latencies, the fifth peak of the waveforms labeled with an “I” sign-mark in Figure 5 was selected for comparison among the responses recorded with electrodes at different locations. The fifth peak was selected as the peak was relatively prominent and stable. The mean latencies were 11.71 (canal), 11.72 (concha), and 11.74 ms (mastoid), and the difference is not significant (p > .05).

Discussions

ABR Amplitude at Different Recording Locations

Previous studies have attempted to assess the effects of various electrode placements on the measurement of responses including the electrode location at the mastoid and ear canal (Bauch & Olsen, 1990; Beattie & Lipp, 1990; Brantberg, 1996; Ruth, Mills, & Ferraro, 1988; Yanz & Dodds, 1985); however, no reports have systematically studied both ABRs and CMs recorded at the same time with recording electrodes placed at the three locations such as at the ear canal, concha, and mastoid, particularly at the concha. Our results indicate that there was no significant difference between Wave I amplitudes recorded at the concha and in the canal, but there was a significant difference between the Wave I amplitudes recorded with the mastoid and concha electrodes. This is consistent with results reported in the past (Bauch & Olsen, 1990; Yanz & Dodds, 1985) in that the Wave I recorded at the ear canal was greater than on the mastoid. As for Wave V, the amplitude was greatest using the mastoid electrode, although there was no significant difference between the responses recorded using the concha and canal electrode.

These results also support the hypothesis that the amplitude is greater as the recording electrode is moved closer to the response-generator site; for example, the ear canal is closer to the cochlea or auditory nerve while the mastoid is closer to the brainstem. Therefore, our data support this hypothesis.

CM Amplitude at Different Recording Locations

This report evaluates the feasibility of using a concha electrode by testing one low frequency and one suprathreshold level as this paradigm should evoke robust responses, which we expect to generate a conclusive result. If it did not, then it would be inappropriate to extend this study to other frequencies and levels as the approach would not be realistic. However, the results show that amplitudes recorded with the concha electrode differ only slightly from those recorded in the canal and that this difference is not statistically significant. In other words, responses measured at the concha are similar to those measured with the canal electrode. This result is not unexpected considering that the concha adjoins the ear canal. Hence, our data support the possibility that the concha electrode can be used as an alternative to a canal recording in the assessment of cochlear function. In fact, other investigators (Noguchi, Nishida, & Komatsuzaki, 1999) have shown similar values for CM detection thresholds (<35 dB nHL) when extratympanic (canal) and transtympanic recordings are compared in human participants with normal hearing. This information suggests that concha recordings may well be useful in screening at-risk populations with possible hearing loss.

Artifacts

The incidence of superimposed artifacts of electrical activities from postauricular muscle occurred more often in the responses recorded at the mastoid. This may be expected as the mastoid electrode was near the muscle. The infrequent occurrence of the artifact with the concha electrode makes it a useful alternative.

Latency

Our results are consistent with previous reports (Beattie, Beguwala, Mills, & Boyd, 1986; Beattie & Lipp, 1990; Beattie & Taggart, 1989) in that changes in electrode placement did not significantly change Wave I and Wave V latency. However, small differences observed may be due to the close proximity of the recording electrodes to the response generators. The mastoid is close to Wave V generators, whereas the canal is closer to generators of the CMs (hair cells) and Wave I (auditory nerve fibers). Unlike the fast conduction of electrons through a metal wire, latency time is required for electrolytes inside tissue to relay the electrical charges from one point to the other.

Clinical Significance

Compared with the canal, the concha electrode is easier to place (a clamp style) and more cost effective (reusable and gold free). It may be preferred by a clinic in a remote area or a developing country which may be unable to obtain a canal electrode or have concerns with the cost of the gold foil electrode. The skin at the concha is easier to clean and less sensitive so that less irritation will occur when testing infants or children. When a canal electrode cannot be used due to lack of cooperation or canal conditions (e.g., disorders, hairy or oily canal), the concha electrode can be used with a sound-field speaker or a supra-aural headphone. Even when using an earplug for acoustic stimulation, no scratching or cleaning of the canal skin is needed; no electrically conductive cream is needed; and no worry of damage to the gold foil is needed when vigorously squeezing a plug to facilitate insertion.

These advantages are not possible when using a gold foil electrode. The cream may cause allergy; vigorously squeezing may damage the foil; and scratching to decrease impedance may be sufficient to cause irritation and also trigger a cough. An unexpected cough in a child may cause bruising within the ear due to bumping on the soft canal skin during scratching. However, in most cases, the gold foil electrode is still an appropriate choice when these limitations are not a concern.

As the responses recorded at the concha and canal are very similar, clinical application with the concha electrode would be very similar to those with the canal electrode. For example, the concha electrode can avoid those limitations associated with OAE measurement (e.g., low-frequency acoustic noises) as described earlier and allow the tester to reach a lower Wave I threshold level than the mastoid electrode (Fria & Sabo, 1980; Schwartz & Berry, 1985). The concha electrode may find application in newborn hearing screening, allowing testing for low-frequency inputs using a simple recording electrode with advantages over canal recordings.

Acknowledgments

Portions of the data were presented at the Annual Convention Meeting of American Academy of Audiology in Denver, CO, in April 18–21, 2007. The authors wish to thank the participants who participated in the experiment for their time and effort; Jane De Pauw for effective editing and proofreading; Kristin King, Brenda Flores, Pinky Raju, Kelly Morefield, and Jennifer Holdman for professional participation in the study and data collection and analysis; Dr. Vicky Zhao, Ms. Kathy Packford, and Dr. Melanie Campbell for insightful discussions of the manuscript; anonymous reviewers for their very valuable comments.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed that they received the following support for their research and/or authorship of this article: Portions of this work were supported by grants from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (M.Z.), Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital Foundation (M.Z.), and research funding from the University of Alberta (M.Z.).

References

- Adrian E. D. (1931). The microphonic action of the cochlea: An interpretation of Wever and Bray's experiments. Journal of Physiology, 71, xxviii–xxix [Google Scholar]

- Attias J., Nageris B., Ralph J., Vajda J., Rappaport Z. H. (2008). Hearing preservation using combined monitoring of extra-tympanic electrocochleography and auditory brainstem responses during acoustic neuroma surgery. International Journal of Audiology, 47, 178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch C. D., Olsen W. O. (1990). Comparison of ABR amplitudes with TIPtrode and mastoid electrodes. Ear Hear, 11, 463–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie R. C., Beguwala F. E., Mills D. M., Boyd R. L. (1986). Latency and amplitude effects of electrode placement on the early auditory evoked response. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 51(1), 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie R. C., Lipp L. A. (1990). Effects of electrode placement on the auditory brainstem response using ear canal electrodes. American Journal of Otology, 11, 314–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie R. C., Taggart L. A. (1989). Electrode placement and mode of recording (differential vs. single-ended) effects on the early auditory-evoked response. Audiology, 28(1), 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantberg K. (1996). Easily applied ear canal electrodes improve the diagnostic potential of auditory brainstem response. Scandinavian Audiology, 25, 147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciorba A., Bovo R., Trevisi P., Bianchini C., Arboretti R., Martini A. (2009). Rehabilitation and outcome of severe profound deafness in a group of 16 infants affected by congenital cytomegalovirus infection. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 266, 1539–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P. (1973). The auditory periphery: Biophysics and physiology. New York: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont J. J. (1976). Electrophysiological study of the normal and pathological human cochlea. I. Presynaptic potentials. Review of Laryngology, Otology and Rhinology, 97(Suppl.), 487–495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro J. A., Durrant J. D. (2002). Electrocochleography. In Katz J. (Ed.), Handbook of clinical audiology (5th ed., pp. 249–273). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro J. A., Nunes R. R., Arenberg I. K. (1989). Electrocochleographic effects of ear canal pressure change. American Journal of Otology, 10(1), 42–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fria T. J., Sabo D. L. (1980). Auditory brainstem responses in children with otitis media with effusion. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology Supplement, 89(3 Pt. 2), 200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveris H., Mann W. (2009). Association between surgical steps and intraoperative auditory brainstem response and electrocochleography waveforms during hearing preservation vestibular schwannoma surgery. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 266(2), 225–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. A., Brown C. J., Abbas P. J., Chi S. L. (2008). The clinical application of potentials evoked from the peripheral auditory system. Hearing Research, 242(1–2), 184–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaguti M., Bergonzoni C., Zanetti M. A., Rinaldi Ceroni A. (2007). Comparative evaluation of ABR abnormalities in patients with and without neurinoma of VIII cranial nerve. Acta otorhino-laryngologica Italica, 27(2), 68–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi Y., Nishida H., Komatsuzaki A. (1999). A comparison of extratympanic versus transtympanic recordings in electrocochleography. Audiology, 38(3), 135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton S. J., Ferguson R., Mascher K. (1989). Evoked otoacoustic emissions and extratympanic cochlear microphonics recorded from human ears. Abstracts of the Twelfth Midwinter Research Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 12, 227(A) [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi T., Akagi M., Ochi K., Kenmochi M., Kinoshita H., Yoshino K. (1996). Diagnostic significance of electrocochleogram and auditory evoked brainstem response in totally or subtotally deaf patients. Acta Otolaryngolica Supplement, 522, 11–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosahl S. K., Tatagiba M., Gharabaghi A., Matthies C., Samii M. (2000). Acoustic evoked response following transection of the eighth nerve in the rat. Acta Neurochirurgica (Wien), 142, 1037–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth R. A., Mills J. A., Ferraro J. A. (1988). Use of disposable ear canal electrodes in auditory brainstem response testing. American Journal of Otology, 9, 310–315 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D. M., Berry G. A. (1985). Normative aspects of the ABR. In Jacobson J. T. (Ed.), The auditory brainstem response (pp. 65–97). San Diego, CA: College Hill Press [Google Scholar]

- Shehata-Dieler W., Volter C., Hildmann A., Hildmann H., Helms J. (2007). Klinische und audiologische Befunde von Kindern mit auditorischer Neuropathie und ihre Versorgung mit einem Cochlea-Implantat. [Clinical and audiological findings in children with auditory neuropathy]. Laryngorhinootologie, 86(1), 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognola G., Ravazzani P., Grandori F. (1995). An optimal filtering technique to reduce the influence of low-frequency noise on click-evoked otoacoustic emissions. British Journal of Audiology, 29, 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wever E. G., Bray C. (1930). Action currents in the auditory nerve response to acoustic stimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 16, 344–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanz J. L., Dodds H. J. (1985). An ear-canal electrode for the measurement of the human auditory brain stem response. Ear Hear, 6(2), 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F. G., Liu S. (2006). Speech perception in individuals with auditory neuropathy. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 367–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Abbas P. J. (1997). Effects of middle ear pressure on otoacoustic emission measures. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 102, 1032–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Davis B., Holdman J., Morefield K., King K., Flores B. (2007). Can the effect of high noise floor on the measurement of low frequency OAE be resolved with an alternative approach? Abstracts of the Twelfth Midwinter Research Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 30, 21 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., King K., Flores B. (2007). What responses can be measured with a concha electrode? AudiologyNow, 100

- Zhang M., Raju P. (2009). Test re-test reliability in recording cochlear microphonic frequencies at the ear canal. Abstracts of the Twelfth Midwinter Research Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 32, 156 [Google Scholar]

- Zollner C., Karnahl T. (1975). Elektrokochleographisches Potentialmuster, an verschiedenen Ableitungsorten Registriert. [Electrocochleographic potential pattern, recorded by different pick-ups]. Journal of Laryngology Rhinology and Otology (Stutt), 54, 681–688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]