Abstract

An Internet survey of individuals with hearing loss was conducted to determine their use of assistive listening devices for face-to-face conversation and, while part of an audience, their satisfaction with assistive listening devices, their interest in the concept of a universal assistive listening device receiver, and their interest in receiving audiologic information and services through the Internet. The 423 respondents who used assistive listening devices found them to be of significant benefit across a range of listening situations. Most respondents were open to the idea of purchasing a personal device that could work both with hearing aids and a range of transmission media. Probably because of the sampling bias inherent in an Internet survey, respondents were inclined to choose Internet-based and peer-based sources of information, and made many suggestions for both improving assistive listening devices and for improving information available about them by using the Internet.

Keywords: assistive listening devices, ALD, Internet, survey

In the summer of 2005, the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Hearing Enhancement (RERC) conducted a Web-based survey of individuals with hearing loss who use hearing aids or cochlear implants, or both. A societal trend toward use of the Internet for purchasing and health information1 had led the RERC to develop an Internet-based peer advisor training course on hearing assistive technology2 and to consider offering other services online. A Web-based survey was viewed as an appropriate method to investigate the characteristics of individuals who might participate in such online services, as well as the types of needs for information they might have in relation to assistive listening devices (ALDs).

The main topical focus of this survey was ALD systems for in-person listening situations such as face-to-face conversation and participation in events as part of an audience. The RERC also wished to learn whether individuals with hearing aids who use ALDs had a need for and would be willing to purchase a universal receiver, that is, a personal device that would interface with the hearing aid and be compatible with a variety of transmission technologies used in listening systems, if such a device were made available.

Assistive listening devices are important adjuncts to hearing aids and cochlear implants. Little opinion research on these devices has been conducted, although individuals with hearing loss have been frequently surveyed about hearing aids3,4 and, occasionally, about clinical services.5,6 Therefore, the RERC also had a general interest in updating information about current problems and issues related to ALDs as perceived by individuals who use them.

Methods

Survey Development

A survey of 24 questions was developed and revised through several drafts with input from the RERC investigators at Gallaudet University and representatives of the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA), a national organization that at the time was named Self-Help for Hard of Hearing People (SHHH). After several revisions, the draft survey was coded for Web presentation. The Web draft was piloted on 5 individuals (4 women, 1 man) who were members of a local HLAA chapter. Four had computer experience, and one was a novice with computers; all were hearing aid wearers. The individual observation of these respondents completing the survey, and their comments about the questions as they answered, were used to revise the survey questions, response-choices, and screen layouts.

The survey was then posted on a secure server at Gallaudet University. The survey was first publicized through flyers handed out at the HLAA 2005 convention. Immediately after the convention, e-mail announcements with links to the survey Web site were sent to online newsletters and listservers aimed at individuals with hearing loss. These included the HLAA membership newsletter and the Beyond Hearing list-server, an online affinity group concerned with hearing loss. E-mail announcements and requests to publicize the survey were also sent to individual chapters of the HLAA. The survey was available online from July through September 2005.

Survey Content and Administration

Screening Question

Informed consent information was presented on the initial page of the questionnaire site, and the respondent indicated approval by clicking on a response button. This introductory page also explained that the survey was for individuals 18 years of age or older with hearing loss. The screening question, “Do you have a hearing loss in one ear or both ears?” followed approval of informed consent. If the answer to the question about hearing loss was “no hearing difficulty,” the respondent was presented with a screen that thanked the individual for his or her interest, but indicated that the survey would not continue.

Navigation

Respondents navigated the survey using navigation buttons (Previous, Next) on each survey page. At the bottom of the page, the number of questions remaining was indicated. Response buttons were programmed to prevent multiple responses to questions where only 1 choice was permitted.

Hearing Level and Hearing Technology

The initial content questions of the questionnaire covered degree of hearing loss in the better ear, style of hearing aid or cochlear implant used on each ear, whether the devices included a telecoil, and length of use of hearing aid and/or cochlear implant by the respondent. Respondents were also asked to rate overall satisfaction with their hearing aids or cochlear implants on a 5-point scale: “very satisfied,” “satisfied,” “neutral (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied),” “dissatisfied,” or “very dissatisfied.”

Listening Situations and Assistive Listening Device Use

In the next group of questions, 5 common listening situations were presented: (1) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting, (2) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a noisy setting, (3) conversation with a group in a quiet setting, (4) conversation with a group in a noisy setting; and (5) as an audience member where the speaker is more than 10 feet away. For each of these situations, 5 questions were posed:

how much difficulty in understanding speech respondents usually experience when using hearing aids or cochlear implants alone (a 5-point scale ranging from “cannot understand speech at all” to “no difficulty”);

how often respondents are in these situations (a 5-point scale ranging from “never” to “very often”);

whether respondents had used ALDs in the past 2 years in that situation (checked or not checked);

whether respondents understand speech better in that situation with ALDs than with a hearing aid (HA) or cochlear implant (CI) alone (a 4-point scale “worse than HA or CI alone,” “about the same,” “better than HA or CI alone” or “much better than HA or CI alone,” plus a choice for “I do not use ALDs in this situation”); and

comfort level using ALDs in each situation (a 5-point scale “very comfortable,” “somewhat comfortable,” “neutral,” “somewhat uncomfortable,” “very uncomfortable” plus a choice for “I do not use ALDs in this situation.”)

This part of the questionnaire also asked respondents to indicate which types of ALD receiver equipment they had used within the past 2 years. The 2-year time limit was included to avoid the potential problem that users might not remember experiences with specific types of receivers in the more-distant past. Sample color photos of receiver types were included to supplement the descriptors in case the descriptors provided were inadequate for some respondents. Respondents were asked to check all types of receivers they had used and to indicate if they had used wired ALDs, wireless ALDs, or both. Respondents were also invited to write in other types of ALD equipment they had used. These write-in responses were later recoded and, where applicable, added to the count by category.

Suggestions and Problems

Respondents were asked whether they had suggestions for improvements to ALDs, and the survey included a comment box for suggestions. Because ALDs are often used in public places where users must borrow receivers, 2 questions addressed users’ experiences in that situation. Respondents were asked to indicate how frequently, if at all, they encountered a variety of problems with borrowed ALDs, including incompatibility of receivers with their hearing aids or cochlear implants, lack of trained staff at the venue, lack of signage, poor sound quality, interference, dead battery, difficulty with controls, and difficulty in monitoring the level of one's own voice while using a borrowed receiver. Respondents were asked if they would be willing to purchase a universal receiver if it were available, and if so, how much they would be willing to pay.

Information Needs and Resources

The next section of the survey asked respondents about the types of media, individuals, and organizations they consulted to obtain information about ALDs as well as other hearing technologies; and what types of information they would like to see made available in or by such information sources. These questions were included to guide the RERC about how best to provide information about ALD-related services. Respondents were asked if they needed and would seek individual guidance about hearing technologies (ALDs, hearing aids, cochlear implants) on the Internet, and were invited to write in suggestions of the kinds of information or help they would use. They were asked to indicate individuals and organizations that had been sources of information used in the past, as well as media they use to seek such information.

Demographic Information

Questions on age, gender, and self-ratings of vision, walking, use of their hands, and general health comprised the final content area of the questionnaire.

Results

Eleven individuals were screened out of the survey because they responded that they did not have hearing loss. An additional 100 individuals visited the site of the survey but for unknown reasons did not answer the questions. Among the 423 respondents with hearing loss who did complete the survey, 67 indicated they had not used ALDs in the previous 2 years. These respondents were not asked other questions about recent use of ALDs but did have the opportunity to complete the other survey items and were included in the analysis of those items.

Demographic Information

Responses to demographic questions are summarized in Table 1. The respondents varied considerably in age, with every age category from 18 to 30 to 81-and-older having at least 5% of the respondents; almost half (49%) were aged 51 to 70. Women comprised 61%. A large majority indicated excellent or good function for vision (88%), walking (88%), ability to use their hands (95%), and general health (92%). These questions on physical function were asked to see if there were relationships between impairments in these areas and situational use of ALDs and satisfaction with them, but there was insufficient variance in the responses to make them usable for that purpose.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables of Respondents

| Variable | Percent |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–30 | 5 |

| 31–40 | 6 |

| 41–50 | 15 |

| 51–60 | 26 |

| 61–70 | 23 |

| 71–80 | 18 |

| ≥81 | 7 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 61 |

| Male | 39 |

| Vision: good or excellent | 88 |

| Walking: good or excelent | 88 |

| Ability to use hands: good or excelent | 95 |

| General health: good or excelent | 92 |

Hearing Level and Hearing Technology

The survey respondents tended to have both significant hearing loss and experience with hearing assistive technology. Characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 2. The 423 respondents included in the analysis were predominantly individuals with severe (30%) or profound (39%) hearing loss, and 28% were in the category of moderate to moderate-severe.

Table 2.

Hearing Level and Hearing Technology

| Variable | Percenta |

|---|---|

| Degree of hearing loss | |

| Mild | 2 |

| Moderate or moderate/severe | 28 |

| Severe | 30 |

| Profound | 39 |

| Not sure | 2 |

| Type of aid(s) usedb | |

| BTE | 75 |

| ITE | 6 |

| ITC or CIC | 6 |

| Cochlear implant | 22 |

| Unilateral | 27 |

| Bilateral | 73 |

Note: BTE = behind the ear; ITE = in the ear; ITC = in the canal; CIC = completely in the canal.

Totals for degree of hearing loss and unilateral/bilateral may not equal 100% because of rounding. Total percentage for type of aid(s) exceeds 100% because many respondents used more than one type.

Respondents using type on one or both ears.

Of the 385 who responded to questions about style of hearing aids for each ear, 73% were bilateral users of hearing aids, cochlear implants, or both. Three-fourths of the sample (75%) used behind-the-ear (BTE) aids on one or both ears, and just over half (51%) used BTE aids bilaterally. Only a small minority used in-the-ear (6%) or in-the-canal/completely-in-the-canal (6%) hearing aids on 1 or both ears. Cochlear implants were used on 1 or both ears by 22% of respondents. Most respondents (89%) had used hearing technology for more than 3 years, and 85% had telecoils in their hearing aids or cochlear implants. Most of the survey respondents (72%) were generally satisfied or very satisfied with their hearing aids or cochlear implants, yet most used ALDs in some situations; 84% indicated that they had used ALDs in the previous 2 years.

Listening Situations and Assistive Listening Device Use

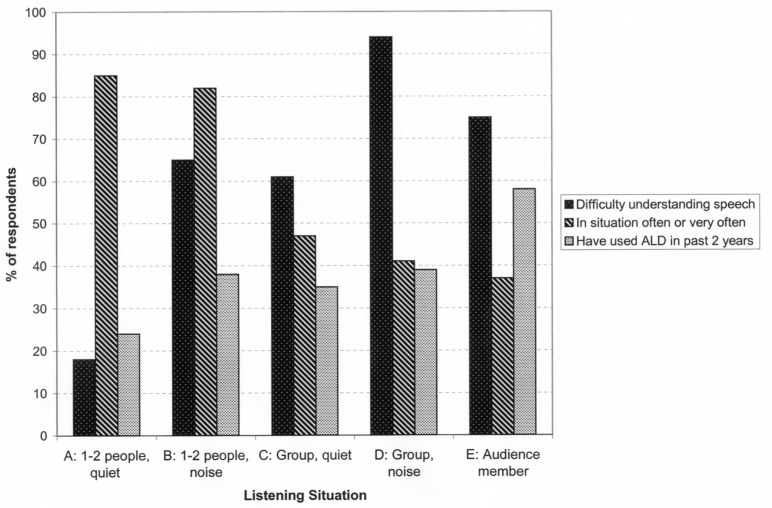

The graph in Figure 1 shows responses to questions about listening: difficulty in hearing speech in a given situation, how often the individual is in that situation, and whether ALDs had been used in that situation in the previous 2 years. In relation to difficulty understanding speech, responses were counted as “difficult” if respondents checked “moderate difficulty,” “great difficulty,” or “cannot understand speech at all.” In relation to frequency in that situation, the graph shows responses indicating “often” or “very often.”

Figure 1.

Responses to the questions of (1) difficulty understanding speech, (2) how often in the situation, and (3) having used assistive listening devices (ALDs) in that situation for listening in 5 specified listening situations: (A) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting; (B) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a noisy setting; (C) conversation in a group in a quiet setting; (D) conversation in a group in a noisy setting; and (E) as a member of an audience when the speaker is at least 10 feet away. “Difficulty understanding speech” indicates a response of “moderate difficulty,” “great difficulty” or “cannot understand speech at all.”

The listening situation with the fewest users of ALDs is also the situation with the fewest respondents reporting difficulty in understanding speech: conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting. It is also the situation that the largest proportion (85%) of respondents indicated they encounter often or very often. Presumably, hearing aids function well enough alone in this situation for almost all of the people in this sample not to report difficulty. The situation in which the largest proportion (94%) of respondents indicated difficulty was as part of a group in a noisy setting. Fewer participants (41%) said they were in a noisy group situation often or very often compared with 82% who indicated they often or very often conversed with just 1 or 2 people in a noisy setting. It is possible that the difficulty of the group situations in noise causes some individuals with hearing loss to avoid them, although we did not directly ask this question.

The only situation in which a majority (58%) of respondents reported using ALDs in the past 2 years was as part of an audience where the speaker is more than 10 feet away. This was also the only situation in which a larger percentage of respondents reported having used ALDs than reported being in the situation frequently. In this situation, typically, a receiver is available (eg, at a conference or in a movie theater) or an audio loop system is present so that no separate receiver is required.

Because the primary focus of the survey was in-person communication rather than telecommunications or entertainment, and because the questionnaire was already quite long, the full set of satisfaction questions about ALDs was not asked about telecommunication and entertainment situations. Respondents were asked simply to indicate if they had used ALDs for listening to the television, telephone, or a music player during the past 2 years. About a third reported using ALDs for television (31%) or telephone (34%), and slightly fewer than one in four (23%) had used ALDs for listening to a music player.

Table 3 summarizes results on types of ALD interfaces to hearing aids and cochlear implants that respondents reportedly had used in the previous 2 years. Most respondents had used more than 1 type of interface (median, 2). Telecoil or room loop use was most common (65%), followed by neckloop (48%). Despite the large proportion of respondents using BTE hearing aids (75%), only 22% reported using direct audio input. Wireless ALDs were more commonly used (48%) than wired ALDs (28%).

Table 3.

General Characteristics of Assistive Listening Devices Used by Respondents in Previous 2 Years

| Interface to Hearing Aid or Cochlear Implant | Percent |

|---|---|

| Telecoil alone and/or room loop specified | 65 |

| Neckloop | 48 |

| Headphones with hearing aid | 28 |

| Direct audio input | 22 |

| Headphones without hearing aid | 18 |

| Silhouette | 14 |

| Link between microphone and receiver | |

| Wireless link (FM, infrared, etc) | 48 |

| Wired link | 28 |

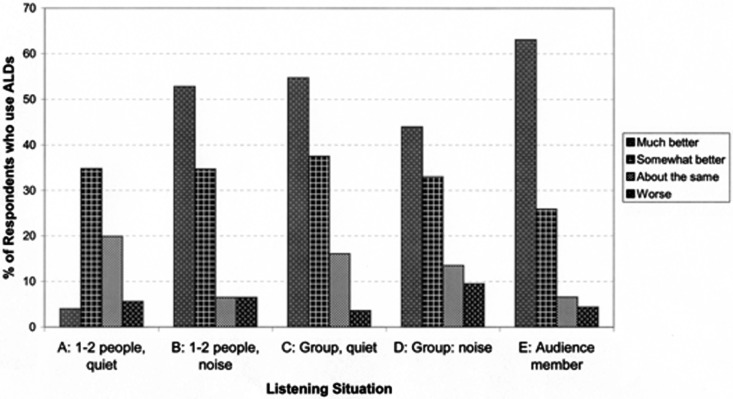

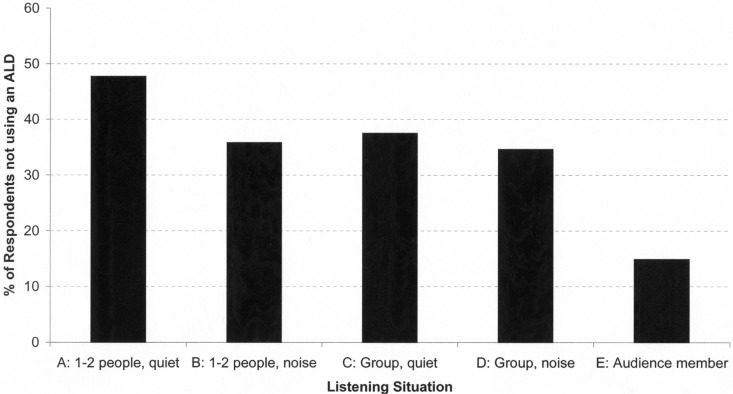

For each listening situation, the questionnaire asked, “In general, when you use assistive listening devices, can you understand speech better than when you use hearing aids or cochlear implants alone?” Responses to this question are displayed in Figure 2. Responses are reported only for those who use ALDs in that situation. Responses reflected a widespread perceived benefit of ALDs for helping individuals with hearing loss to understand speech, among those who use the devices. Respondents who use ALDs in each situation overwhelmingly indicated somewhat better or much better speech understanding with ALDs (Figure 2). Conversely, as shown in Figure 3, a fairly large minority of respondents reported that, “I do not use ALDs in this situation.” This response ranged from 48 individuals for the audience situation up to 114 individuals for conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting. It is not known if their lack of use is due to lack of benefit compared with hearing aids alone.

Figure 2.

Responses to 5 questions about ability to understand speech better when using assistive listening devices (ALDs) compared with hearing aids or cochlear implants alone, for specified listening situations: (A) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting (161 respondents); (B) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a noisy setting (199 respondents); (C) conversation in a group in a quiet setting (193 respondents); (D) conversation in a group in a noisy setting (200 respondents); and (E) as a member of an audience when the speaker is at least 10 feet away (274 respondents). Respondents were those who use ALDs in that situation.

Figure 3.

Responses indicating “I do not use ALDs in this situation” for 5 specified listening situations: (A) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting (308 respondents); (B) conversation with 1 or 2 people in a noisy setting (309 respondents); (C) conversation in a group in a quiet setting (307 respondents); (D) conversation in a group in a noisy setting (306 respondents); and (E) as a member of an audience when the speaker is at least 10 feet away (322 respondents). ALDs = assistive listening devices.

The questionnaire asked respondents to rate their comfort level in using ALDs by situation. Among users of ALDs, the reported comfort levels were generally good. The situation eliciting ratings of discomfort from the most respondents (“somewhat” or “very uncomfortable”) was conversation in a group in a noisy setting. In this case, 34% of respondents indicated discomfort. In contrast, only 14% of those who answered reported discomfort in using ALDs in a conversation with 1 or 2 people in quiet. Responses indicating discomfort for other situations were 14% to 34%.

Respondents were provided an opportunity to give open-ended comments on issues of comfort when using ALDs, and 112 wrote comments relevant to comfort. These comments were coded by whether they were positive, negative, neutral, or situation-dependent, and whether they were related to social comfort or system performance. Nearly half of the comments (47%) were positive, and many of the comments noted that the ability to hear and understand speech trumped any social discomfort they may have experienced at one time or another. Among those comments that were negative toward comfort (37%), performance and usability issues were more often mentioned than issues of social discomfort.

Suggestions and Problems

Suggestions for improvements to ALDs were made by 181 respondents, and some respondents offered more than 1 suggestion. The 226 comments were coded into general categories. The most frequent suggestions for improvement were to:

Reduce cost (29 comments)

Improve portability or reduce size (28 comments)

Eliminate interference (23 comments)

Make the devices sturdier and more reliable (16 comments)

Provide multiple microphones (13 comments)

Some respondents offered specific ideas for design improvements, for example:

Put a microphone on the receiver to let me hear my voice

Better/multiple microphones to avoid passing the microphone to each speaker

Lights to show they are on

Some style, some color, some “snazz”

Make them look like personal stereos or music players

Storage for wires and earbuds within the receiver so wires do not get damaged and extra earbuds are on hand if called for

Better battery life

Responses related to use of ALDs borrowed in a public venue are shown in Table 4. Of the 276 respondents (83% of recent ALD users) who indicated that they had checked out an ALD in a public place, 70% to 85% had sometimes, often, or very often experienced problems related to system performance, compatibility, usability, and ability to locate the place to borrow a receiver (Table 3). The most frequently noted problems had to do with inadequate signage for locating ALDs in public venues and finding staff who were trained in how to use the system. A smaller percentage had experienced problems such as difficulty with controls (35% at least sometimes), and difficulty controlling the level of their own voices (55% at least sometimes) while using the ALDs.

Table 4.

Difficulties Reported With Assistive Listening Device Receivers Obtained in Public Venues

| Problem | Very Often or Often, % (n = 276) | Very Often, Often, or Sometimes,% (n = 276) |

|---|---|---|

| Staff were not trained in operating the equipment | 67 | 85 |

| No signs indicating where to check out the receiver | 65 | 85 |

| Poor sound quality | 51 | 67 |

| Device would not work with my aid/implant | 47 | 77 |

| Interference or buzzing | 44 | 78 |

| Dead battery | 34 | 70 |

| Difficulty with own voice level/control | 27 | 55 |

| Difficulty with controls | 12 | 35 |

One possible solution to some of the problems encountered by ALD users in public venues would be to develop a universal receiver for purchase by individuals with hearing loss. Slightly more than three fourths (76%) of respondents indicated a willingness to purchase such a device. Of those, 22% would pay less than $100, 33% would pay $101 to $300, and 20% would pay more than $300. Only 5% were not willing to buy, and the rest (19%) were not sure.

Information Needs and Resources

Responses to questions about sources of past information and currently used media for information on hearing technology have been aggregated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Sources of Information Respondents Consult on Assistive Listening Devices and Other Hearing Technology

| Information Source | Sample That Checked This Item, % (n = 423) |

|---|---|

| Consumer organizations (eg, SHHH) | 73 |

| Meetings and conferences | 68 |

| Word of mouth | 67 |

| Internet | 62 |

| Peers with hearing loss | 62 |

| Audiologists | 59 |

| Magazines | 57 |

| Hearing technology companies | 49 |

| Catalogs | 27 |

| Other hearing health professionals | 22 |

| Books | 20 |

| Newspapers | 18 |

| Professional associations (eg, ASHA, AAA) | 12 |

Note: SHHH = Self-Help for Hard of Hearing People; ASHA = American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; AAA = American Academy of Audiology.

Most respondents reported having knowledge about hearing technology; only 18% considered themselves novices. Their most frequently selected sources of information on hearing technology tended to be peer-oriented, with consumer organizations, peers who have hearing loss, and meetings listed as the major sources of information. Audiologists were the most commonly cited (59%) nonpeer source of information.

When asked if they would be interested in receiving individual guidance and help about any type of hearing technology over the Internet, 62% said they would use this type of service, 13% would not, and 24% were not sure. More than 200 respondents also volunteered suggestions of the types of guidance they would find helpful. These open-ended responses were coded, and the most frequent categories of suggestions were, in rank order:

Easy-to-understand factual information about ALDs, including new devices, how they work, troubleshooting, pictures/videos

Guides similar to Consumer Reports articles that provide unbiased comparisons based on evaluations to help individuals with hearing loss with selection of ALDs

Information on hearing aids and cochlear implants

Information on where to rent or purchase ALDs

Consumer reviews

Financing/payment information

Examples of the types of Internet-based services respondents cited as of interest included:

Explanations in simple terms about how the systems work

Online “ask-the-expert” chats, access by e-mail

Individual consultation based on individual hearing loss

Experienced persons available online to help with troubleshooting

Information on repairs

Discussion

A survey through the Internet was selected as the methodology for this study because the hearing aid/cochlear implant users of interest are those who use the Internet and who might avail themselves of services offered by the RERC online. The recruitment methods also made use of Internet resources of newsletters and listservers serving individuals with hearing loss who already are active users of the medium for seeking information.

Although we did not ask about membership in organizations, it is likely that a large number of respondents were affiliated with the HLAA, because that organization was used as a major avenue for recruitment. As a result, the survey sample was biased toward individuals who have knowledge of hearing technology, who use ALDs, and who have more severe degrees of hearing loss than is found in the overall population of people with hearing loss. Thus, the results cannot be generalized beyond this special group. To illustrate, 58% of this sample indicated that they had used ALDs in the previous 2 years in a situation where they were part of an audience and the speaker was more than 10 feet away. In contrast, a very small minority of respondents to MarkeTrak VI in 2001 indicated having used 1 or more of 5 ALDs asked about in the survey for listening in public venues or for watching television (1%-7% of the sample, depending on the ALD in question).4

About three fourths of the respondents to this survey used either bilateral BTEs (51%), or at least 1 cochlear implant (22%). The profile of respondents to the survey reinforces the finding of the 2001 MarkeTrak VI survey4 that ALD use is associated with more severe degrees of hearing loss. The sample might be characterized as “power users” of hearing technology, and their responses give insight into what might be considered a core group of individuals who are proactive about hearing technology and interested in issues related to hearing loss.

Despite these marked differences in characteristics between respondents to this survey and respondents to the larger and more generalizable MarkeTrak sample, their opinions on satisfaction with their hearing aids were similar. Of respondents to our Internet survey, 72% were satisfied or very satisfied, and 68% of respondents provided the same ratings to their hearing instruments in MarkeTrak VII (with higher percentages of that sample expressing satisfaction for new hearing instruments). Many improvements desired by more than half of the MarkeTrak sample (2001 survey) are similar to improvements desired in ALDs in this Internet survey.7 Examples include lowering price, improving reliability (“should not break down as much” in the MarkeTrak survey), and reducing interference (“less whistling and buzzing” in the MarkeTrak survey). Thus, it is possible that the samples differ less than might be assumed when it comes to their need for improvement in and information about hearing technology.

Respondents indicated that ALDs provide very substantial benefit to them, compared with hearing aids alone, when they are part of an audience and the speaker is at least 10 feet away. The benefit of ALDs for this situation was cited by nearly all who had used an ALD for this purpose in the past 2 years, with 89% indicating somewhat or much better performance. Comfort levels were also high for this situation.

Borrowing an ALD in a public venue is often fraught with difficulty for many users, however. The problems experienced by the largest number of users were associated with staff not knowing how to use the device and the lack of clear signage explaining how to check them out. Performance problems were also commonplace. This situation is one that clearly needs to be rectified for individuals to be able to make the best use of their hearing ability in public venues. To some extent, the problem could be an issue of public policy implementation, suggesting that accessibility provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act and enforcement of those provisions could be too weak in relation to device quality and availability.

Technology improvement could also alleviate the problems encountered. For example, industry cooperation on the development of a universal (or nearly universal) personal-use receiver could do much to extend the benefits of ALDs to more audience-listening situations. Respondents are clearly open to the idea of a personal receiver compatible with multiple transmission technologies. Although almost all of this survey's respondents are willing to purchase such a device, few are willing to pay in excess of $300 for one. Still, a well-designed device that alleviates the problems frequently encountered might attract more willingness to pay than is indicated in a questionnaire such as this one, which presents it as a concept rather than a reality.

A situation with a high degree of listening difficulty, but lower ratings for ALD benefit compared with hearing aids alone, is conversation with a group in a noisy situation. This listening situation was rated by 94% of respondents as of moderate difficulty, severe difficulty, or resulting in a complete inability to understand speech (Figure 1). The data reflect the relative limitation in usefulness of ALDs in this situation compared with the audience situation; 23% of respondents noted that ALDs perform about the same, or even worse, than hearing aids or cochlear implants alone (Figure 2). In addition, a larger percentage of respondents indicate discomfort in using ALDs in this situation compared with other situations. Written comments across several questions noted that passing the microphone is a barrier to usability. Because this is a frequently encountered situation, it deserves continued attention from industry for improvements to ALDs and other hearing technology as well.

Even for respondents with severe or profound hearing loss, the data indicate that hearing aids and cochlear implants (supplemented, presumably, by speechreading) function well for conversation with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting. Responses to the survey indicate a high degree of overall satisfaction with users’ hearing aids and low difficulty in conversations with 1 or 2 people in a quiet setting. The responses thus reinforce the notion of ALDs as being most beneficial for group listening rather than individual conversation.

There was some indication, although the survey did not explore this in depth, that respondents view the cost of owning devices to be a barrier to use in situations where they are not loaned a receiver. In an open-ended question, respondents most frequently cited reduction in cost as a desired improvement. In addition, the situation which had the largest number of ALD users was the one in which a receiver is typically provided rather than purchased.

Because the respondents were Internet users and many were affiliated with organizations of hard-of-hearing people, it is not surprising that they indicated a clear preference for consumer-oriented sources of information and for the Internet as a medium rather than traditional print media and even professional contacts. Unlike individual consultations with professionals, the Internet has the advantage of the ability to refresh information, and individuals with hearing loss can turn to it repeatedly for updates on technology. As noted by Ross and Bally,2 other surveys show a disparity between audiologists’ claims to have provided clients information about ALDs and clients’ beliefs that they have been provided this information during contact with the professional. Given this disparity, it is not surprising that the ability to find materials online at any time is valuable to individuals who are actively involved in addressing their hearing loss.

Conclusion

It appears that there is ample opportunity to serve this group of respondents with new online information targeted at objective reviews across ALDs, consumer reviews, easy-to-understand information about ALDs, and with individual professional guidance on use, selection, and just-in-time online troubleshooting. Such information online by trusted professional sources might also, in the long run, serve clients well beyond this sample, clients who are not affiliated with organizations and who are not “power users,” but who are nonetheless part of the ever-growing numbers of people who use the Internet daily. Taking care of clients’ information needs online could save time in the clinic, where individual counseling may be less and less feasible over time due to cost and other managed-care constraints.

Acknowledgment

Much of the information in this article was presented orally at the State of the Science Conference of the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Hearing Enhancement, Gallaudet University, September 18–19, 2006.

This article was developed under grant # H133E-03006-06 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), U.S. Department of Education. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and endorsement by the Federal Government should not be assumed.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dennis Cregan and Linda Kozma-Spytek of Gallaudet University, the Hearing Loss Association of America, and individuals who responded to the survey.

References

- 1.Rainie L. How the Internet is Changing Consumer Behavior and Expectations. Speech to the Society of Consumer Affairs Professionals in Business, May 9, 2006. Pew Charitable Trusts. Available at: http://www.pewtrusts.com/pdf/PewInternetSOCAP050906.pdf Accessed March 2, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross M, Bally S. Peer mentoring: its time has come. Audiol Online. October 17, 2005. Available at: http://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/article_detail.asp?article_id=1448 Accessed March 2, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VII: hearing loss population tops 31 million. Hear Rev. 2005;12(7): 16–29 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VI: factors impacting consumer choice of dispenser and hearing aid brand; use of ALDs and computers. Hear Rev. 2002;9: 14–23 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prendergrast SG, Kelly LA. Aural rehab services: survey reports who offers which ones and how often. Hear J. 2002;55: 30–35 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stika CJ, Ross M, Cuevas C. Hearing aid services and satisfaction: the consumer viewpoint. Hear Loss. 2000;23: 25–31 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VI: consumers rate improvements sought in hearing instruments. Hear Rev. 2002;9: 18–22 [Google Scholar]