Abstract

Recent surveys and reports suggest that many athletes and bodybuilders abuse anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS). However, scientific data on the cardiac and metabolic complications of AAS abuse are divergent and often conflicting. A total of 49 studies describing 1,467 athletes were reviewed to investigate the cardiovascular effects of the abuse of AAS. Although studies were typically small and retrospective, some associated AAS abuse with unfavorable effects. Otherwise healthy young athletes abusing AAS may show elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein and low levels of high-density lipoprotein. Although data are conflicting, AAS have also been linked with elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure and with left ventricular hypertrophy that may persist after AAS cessation. Finally, in small case studies, AAS abuse has been linked with acute myocardial infarction and fatal ventricular arrhythmias. In conclusion, recognition of these adverse effects may improve the education of athletes and increase vigilance when evaluating young athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities.

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) are synthetic derivatives of testosterone that were originally developed in the late 1930s.1 At present, the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved a variety of AAS to treat wasting syndrome in human immunodeficiency virus infection, hypogonadism, anemia accompanying renal and bone marrow failure, endometriosis, and cancer.2,3 Unfortunately, AAS are frequently abused and have recently been linked to the tragic deaths of celebrated professional athletes in the United States.4,5 Indeed, recent estimates suggest that >3 million individuals in the United States abuse AAS, including nandrolone decanoate, methandienone, stanozolol, androsterone, and androstane.6,7 This rampant abuse led Congress to enact the Anabolic Steroids Control Act in 1990, requiring that anabolic steroids be added to Schedule 3 of the Controlled Substances Act.8,9 All major professional sports organizations ban the use of AAS. Regardless, a recent report by Mitchell et al10 showed that >29 major league baseball players tested positive for AAS abuse within the past 4 years. Many effects of AAS abuse are unclear. Although side effects are rare at therapeutic doses, abusers typically use 5 to 15 times the recommended clinical doses of AAS.6,11,12 At such doses, general adverse effects include dose-dependent suppression of testicular function, gynecomastia, hepatotoxicity, and psychologic disorders.6,11,12 Cardiac and metabolic effects of AAS abuse are particularly unclear, although there are alarming reports of cardiac morbidity and mortality. Moreover, athletes often abuse AAS for years, prolonging the potential for harm.13–15 The purpose of this review is to synthesize the recent published reports on the cardiac and metabolic effects of AAS abuse in athletes.

Methods

We reviewed human studies retrieved from the PubMed, eMedicine, Heart Online, and Cochrane Databases in the English language. Inclusion terms were “anabolic steroid,” “body builder,” “athlete,” and “steroid user,” used alone or in combination with the terms “ventricular hypertrophy,” “hypertension,” “lipoprotein,” “sudden death,” “myocardial infarction” (MI), “cardiac,” “arrhythmia,” “tachycardia,” and “fibrillation.” The only exclusion term was “animal.” In turn, a review of primary sources for each report was also conducted to find additional sources pertaining to their parent topics. Review of published reports was limited to the period from January 1, 1987, to December 31, 2009, because widespread testing became available in the United States and Europe at the end of 1986.

Results

We retrieved a total of 49 reports describing a total of 1,467 athletes (median 15 subjects/study). In aggregate, studies evaluated lipoprotein concentrations in 643 subjects, blood pressure in 348, left ventricular (LV) dimensions in 561, and sudden death in 102. We also report 4 key animal studies whose results shed insights into potential mechanisms linking AAS abuse with cardiovascular disease.

Clinical pharmacology of AAS

AAS include many agents with chemical structures derived from cholesterol that are synthesized in the liver and then metabolized in the adrenal glands and testes to AAS. Their structure resembles that of corticosteroids, explaining some similarities in actions in terms of renal sodium retention and hypertension.

The public health problem: prevalence of AAS abuse

AAS are abused by athletes primarily to increase lean muscle mass, enhance appearance, and improve performance.16–18 Self-reported rates of abuse in bodybuilders range from 29% to 67%.19–21 In a 1996 British survey of steroid abuse in competitive gymnasiums (albeit with few women), 29% of respondents admitted using AAS.19 In an American study of 380 competitive bodybuilders in 1989, 54% of men and 10% of women admitted using AAS on a regular basis,20 while 10 of 15 bodybuilders from an American power-lifting team admitted to taking AAS in a more recent study.21

Mortality in AAS abuse: the importance of cardiovascular causes

Mortality appears to be significantly higher in AAS abusers than in nonabusing athletes. In a retrospective case-cohort study of 248 AAS users and 1,215 controls (average age 23 years), 12 AAS users died during the study period,22 providing a standard mortality ratio of 20.43 (95% confidence interval 10.56 to 35.70). Of the 1,215 athletes who did not abuse AAS, 22 died during the study period, resulting in a standard mortality ratio of 6.02 (95% confidence interval 3.77 to 9.12).22 Although the exact causes of death were difficult to ascertain, a postmortem study of male Caucasian AAS abusers (aged 20 to 45 years) suggested primary cardiac pathology in 1/3,23 while a recent case-control study24,25 suggested cardiac causes in 2/3 of deaths, with others being attributed to suicide, hepatic coma, and malignancy. Many mechanisms have been proposed to explain potential adverse cardiovascular events of AAS.

Potential mechanisms

The physiologic and pharmacologic mechanisms of action of AAS on vascular structure and function are incompletely understood. AAS bind to androgen receptors in the heart and major arteries,26 and physiologic levels (e.g., of testosterone) may have a beneficial effect on coronary arteries via endothelial release of nitric oxide and inhibition of vascular smooth muscle tone.27,28 Conversely, animal studies show that abused AAS such as nandrolone at appropriately high doses may reverse this vasodilator response and lead to growth-promoting effects on cardiac tissue, as seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, followed by apoptotic cell death.29–31 These effects are likely mediated by membrane receptor–second messenger cascades that increase intracellular Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ mobilization from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.32 Increases in Ca2+ affect mitochondrial permeability, leading to the release of apoptogenic factors such as holocytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, and caspase-9.33 Notably, AAS dosing associated with sudden cardiac death, MI, ventricular remodeling, and cardiomyopathy is related to apoptosis.30 These findings may explain clinical observations that AAS can lead to myocardial death without coronary thrombosis or atherosclerosis.34,35

AAS and abnormal plasma lipoproteins

AAS abuse has been linked with abnormal plasma lipoproteins (Table 1). Several studies suggest that AAS abuse in athletes increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels by >20%14,36–38 and decrease high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels by 20% to 70%.13,14,37,39–44 More generally, steroid hormones alter serum lipoprotein levels via the lipolytic degradation of lipoproteins and their removal by receptors through modification of apolipoprotein A-I and B synthesis. Although some studies have shown an association between AAS and elevated LDL, no definitive mechanism has been established. Baldo-Enzi et al39 suggested that serum LDL levels may increase through the induction of the enzyme hepatic triglyceride lipase and catabolism of very low density lipoprotein. Hepatic triglyceride lipase induction may also catabolize HDL and reduce its serum levels.45 By some estimates, these lipoprotein abnormalities increase the risk for coronary artery disease by three- to sixfold.14,45

Table 1.

Effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse on lipoprotein concentration

| Study | Abused Agent | Dosage of AAS (mg/week) | Subjects, Age (years)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users Ex-Users Controls | Users LDL (mg/dl) HDL (mg/dl) | Ex-users LDL (mg/dl) HDL (mg/dl) | Controls LDL (mg/dl) HDL (mg/dl) | |||

| Baldo-Enzi et al39,¶ | Methenolone enanthate | 100–300 | 14, 27 ± 5 | 129 ± 37 | — | 119 ± 17 |

| Testosterone cypionate | 200–300 | 17, 25 ± 4 | 27 ± 11|| | — | 48 ± 6 | |

| Fröhlich et al40 | — | — | 13, 27 ± 4 | 154 ± 58 | — | 121 ± 22 |

| 11, 27 ± 7 | 23 ± 16‡ | — | 34 ± 7 | |||

| Hartgens et al41,¶ | Stanozolol | 30–140 | 19, 31 ± 7 | — | — | — |

| Nandrolone decanoate | 8–250 | — | 17 ± 9|| | — | 47 ± 22 | |

| 16, 33 ± 5 | ||||||

| Lajarin et al36 | Stanozolol | 50–100 | 2, 27 ± 3 | 238 ± 8 | — | — |

| Methenolone enanthate | 100 | — | 14 ± 0.4 | — | — | |

| — | ||||||

| Lane et al42 | Testosterone | — | 10, 26 ± 7 | 113 ± 27 | 86 ± 23 | 82 ± 12 |

| Nandrolone | 8, 32 ± 7 | 27 ± 16†,|| | 51 ± 16 | 51 ± 12 | ||

| Stanozolol | 10, 24 ± 4 | |||||

| Lenders et al14,¶ | Methenolone | 385–690 | 20, 26 ± 8 | 206 ± 21*,‡ | 156 ± 9 | 130 ± 13 |

| Testosterone | 310–355 | 42, 28 ± 7 | 27 ± 3†,|| | 42 ± 2 | 46 ± 2 | |

| Oxymetholone | 580–650 | 13, 28 ± 5 | ||||

| McKillop and | Stanozolol | 280 | 8, 25 ± 4 | 243 ± 50|| | — | 122 ± 27 |

| Ballantyne37 | Nandrolone decanoate | 200 | — | 16 ± 11|| | — | 43 ± 12 |

| 8, 25 ± 3 | ||||||

| Palatini et al38,¶ | Testosterone enanthate and propionate | 50–1,500 | 10, 27 ± 8 | 153 ± 34§ | — | 107 ± 41 |

| Stanozolol | 50–150 | — | 30 ± 10 | — | 57 ± 13 | |

| 14, 28 ± 5 | ||||||

| Sader et al13 | Stanozolol | — | 10, 37 ± 3 | — | — | — |

| Nandrolone | — | 23 ± 4|| | — | 55 ± 4 | ||

| Creatine | 10, 34 ± 3 | |||||

| Urhausen et al43 | Oral (i.e., mesterolone) and intramuscular | 1,030 | 17, 31 ± 5 | 139 ± 37 | 119 ± 30 | — |

| 15, 38 ± 7 | 17 ± 11† | 43 ± 11 | — | |||

| AAS (i.e., stanozolol, nandrolone) | — | |||||

| Zuliani et al44 | Testosterone enanthate and propionate | 750–1,500 | 6, 28 ± 2 | — | — | — |

| — | 19 ± 8|| | — | 49 ± 6 | |||

| Human growth hormone | 8, 26 ± 2 | |||||

Data are expressed as ranges, numbers, or mean ± SD. The control group included bodybuilders who denied AAS abuse.

p <0.05 and

p <0.001 versus ex-users;

p <0.05,

p <0.01, and

p <0.001 versus controls.

Other unspecified AAS abused.

In a study of 88 bodybuilders who tested positive for AAS, Lenders et al14 showed that AAS abusers had significantly higher LDL and lower HDL levels than nonabusers. Other studies have confirmed these effects (Table 1). Although actual lipoprotein levels vary among studies, LDL levels as high as 596 mg/dl46 and HDL levels as low as 14 mg/dl46 have been noted in otherwise healthy athletes who abuse AAS. We have observed a markedly low HDL level of 5 mg/dl in a bodybuilder who admitted to AAS abuse (unpublished observations). Abnormalities of HDL and LDL may arise within 9 weeks of AAS self-administration (Table 1).14 This time of onset and duration is supported in numerous studies.13,36–42,44,47–57 Fortunately, lipid effects seem to be reversible (Table 1)14,42,55 and may normalize 5 months after discontinuation.14 Nevertheless, further studies are warranted, because the duration of effect is longer than would be expected from the terminal half-lives of these agents (typically 7 to 12 days).58

AAS may elevate blood pressure

The relation between AAS abuse and blood pressure is controversial. A link between AAS abuse and elevated blood pressure has been observed in some studies,14,43,59,60 whereas others have shown no association.13,38,42,59,61–67 When hypertension is observed, it likely follows renal retention of sodium from AAS.12,68 Blood pressure response to AAS abuse typically shows a dose-response relation. In a retrospective study, Urhausen et al43 reported that mean arterial pressure in AAS users was elevated, in the prehypertensive and stage I hypertensive range as defined in the “Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure,” compared to former users or nonusers. Other studies support these data (Table 2). Although actual elevations vary (Table 2), blood pressures as high as 195/110 mm Hg have been recorded in otherwise healthy athletes with no other identifiable cause.69 Again, the effects of AAS abuse on blood pressure may persist for long periods; some studies have shown persistent elevations for 5 to 12 months after discontinuing AAS.14,43 Although this may reflect the prolonged half-lives of depot AAS preparations,58 it may also reflect the fact that self-reporting of discontinuation is unreliable. In some studies, AAS remain detectable after self-reported discontinuation.14,43,58 Furthermore, there is variability in dosing regimens and supplemental substance use in numerous studies.14,43,59

Table 2.

Effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids on blood pressure

| Study | Abused Agent | Dosage (mg/week) | Subjects, Age (years) Users Ex-Users Controls | Blood Pressure (mm Hg)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users Systolic Diastolic | Ex-Users Systolic Diastolic | Controls Systolic Diastolic | ||||

| D’Andrea et al61,|| | — | 525 (90) | 20, 35 ± 3 | 140 ± 7 | — | 131 ± 9 |

| — | 84 ± 4 | — | 81 ± 5 | |||

| 25, 34 ± 3 | ||||||

| De Piccoli et al62 | — | — | 14, 26 ± 5 | 142 ± 11 | 140 ± 10 | 136 ± 12 |

| 9, 26 ± 5 | 83 ± 5 | 83 ± 5 | 87 ± 9 | |||

| 14, 26 ± 4 | ||||||

| Di Bello et al59 | Testosterone propionate | 300–500 | 10, 33 ± 3 | 135 ± 19 | — | 138 ± 8 |

| Methenolone enanthate | 300–600 | — | 89 ± 12‡ | — | 87 ± 8 | |

| Testosterone cypionate | 200–350 | 10, 30 ± 7 | ||||

| Hartgens et al63,|| | Nandrolone decanoate | 20–250 | 17, 32 ± 7 | 139 ± 13 | — | 134 ± 8 |

| Stanozolol | 30–140 | — | 85 ± 12 | — | 81 ± 7 | |

| 15, 33 ± 5 | ||||||

| Karila et al64,|| | — | 770 (310) | 16, 30 ± 5 | 131 ± 13 | — | 131 ± 13 |

| — | 76 ± 10 | — | 77 ± 9 | |||

| 15, 26 ± 3 | ||||||

| Krieg et al65,|| | — | 820 (620) | 14, 36 ± 7 | 135 ± 10 | — | 130 ± 5 |

| — | 85 ± 5 | — | 85 ± 5 | |||

| 11, 36 ± 11 | ||||||

| Kuipers et al66 | Nandrolone decanoate | 200–400 | 7 | 134 ± 14 | — | 127 ± 11 |

| Testosterone | 2000 | — | 86 ± 14 | — | 74 ± 8 | |

| Stanozolol | 150–300 | 6 | ||||

| Lane et al42 | Testosterone | 10, 27 ± 7 | 119 ± 7 | 121 ± 7 | 125 ± 13 | |

| Nandrolone | 8, 32 ± 7 | 81 ± 4 | 67 ± 18 | 72 ± 14 | ||

| Stanozolol | 10, 24 ± 4 | |||||

| Lenders et al14,|| | Methenolone | 385–690 | 20, 26 ± 8 | 121 ± 2† | 119 ± 2† | 114 ± 2 |

| Testosterone | 310–360 | 42, 28 ± 7 | 74 ± 2 | 72 ± 1 | 71 ± 2 | |

| Oxymetholone | 580–650 | 13, 28 ± 5 | ||||

| Nottin et al67 | — | 6, 41 ± 6 | 132 ± 10 | — | 122 ± 11 | |

| — | 87 ± 8 | — | 77 ± 12 | |||

| 9, 38 ± 6 | ||||||

| Palatini et al38,|| | Testosterone enanthate and propionate | 50–1,500 | 10, 27 ± 8 | 124 ± 14 | — | 128 ± 11 |

| Stanozolol | 50–150 | — | 80 ± 14 | — | 74 ± 7 | |

| 14, 28 ± 5 | ||||||

| Riebe et al60,|| | Stanozolol | 110–200 | 9, 25 ± 4 | 133 ± 8† | — | |

| Testosterone | 250–400 | — | 83 ± 7 | — | 123 ± 10 | |

| Nandrolone decanoate | 200–400 | 10, 28 ± 4 | 77 ± 7 | |||

| Sader et al13 | Stanozolol | 10, 37 ± 3 | 127 ± 3 | — | 119 ± 4 | |

| Nandrolone | — | 74 ± 5 | — | 71 ± 5 | ||

| Creatine | 10, 34 ± 3 | |||||

| Urhausen et al43,|| | — | 1,030 | 17, 31 ± 5 | 140 ± 10*,§ | 130 ± 5 | 125 ± 10 |

| 15, 38 ± 7 | 85 ± 10 | 85 ± 5 | 80 ± 10 | |||

| 15, 28 ± 5 | ||||||

Data are expressed as ranges, numbers, or mean ± SD. The control group included bodybuilders who denied AAS abuse.

p <0.05 versus ex-users;

p <0.05,

p <0.01, and

p <0.001 versus controls.

Other unspecified AAS abused.

Importantly, the link between AAS abuse and elevated blood pressure is not seen in all studies.13,38,42,59,61–67 In a small cross-sectional study, Palatini et al38 did not find any difference in blood pressure between 10 AAS users and 14 age-matched controls. Measurements were made when users were taking AAS and during the withdrawal stage of cycling. Misclassification of athletes was minimized by measuring gonadratropin levels, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone, which decreased significantly in users. In another cross-sectional study by D’Andrea et al,61 blinded blood pressure measurements in 20 AAS-abusing athletes did not differ significantly from those in 25 age-matched AAS-free bodybuilders using the same exercise protocol, although blood pressure was non-significantly elevated (p >0.05). Moreover, Lenders et al14 did not show elevated blood pressure in AAS users compared with nonusers in a larger population. Possible explanations include lower AAS doses in those abusers or, speculatively, undeclared abuse in the “control” population in whom occult AAS abuse was not tested for. Another confounding variable that some investigators neglect to report relates to cuff size. In athletes with larger arms, regular sized blood pressure cuffs could overestimate blood pressure. Analysis is complicated further by variability in exercise regimens, variability in dosing and duration of AAS use, and potential biases in unblended studies. Clearly, additional studies are necessary to definitively reveal a link between AAS and blood pressure.

AAS and LV hypertrophy (LVH)

Athletes abusing AAS often exhibit LVH (Table 3).13,15,43,64,65,70,71 However, because the hypertrophy may relate to increased afterload from isometric exercise,72 the interpretation of LVH in elite athletes who admit to AAS abuse is complex. Possible associations between AAS and LVH may be explained as secondary to hypertension or as a direct effect on the myocardium. Notably, studies in isolated human myocytes have shown that AAS bind to androgen receptors and may directly cause hypertrophy,73–75 potentially via tissue up-regulation of the renin-angiotensin system.76 Indeed, clinical studies suggest a distinct form of LVH in AAS abusers, suggested by textural changes in the myocardium on echocardiography before the onset of overt LVH.59

Table 3.

Effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse on cardiac dimensions

| Study | Abused Agent | Dosage (mg/week) | Subjects, Age (years) Users Ex-Users Controls | IVS (mm)

|

PW (mm)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | Ex-Users | Controls | Users | Ex-Users | Controls | ||||

| D’Andrea et al61,|| | — | 525 (91) | 20, 35 (3) | 12.3 (1.3) | — | 11.2 (2.1) | 11.8 (1.4) | — | 10.4 (2.1) |

| — | |||||||||

| 25, 34 (3) | |||||||||

| De Piccoli et al62 | — | — | 14, 26 (5) | 11 (0.8) | 10.6 (1.0) | 10.5 (0.8) | 10.3 (0.8) | 9.8 (0.9) | 9.8 (0.7) |

| 9, 26 (5) | |||||||||

| 14, 26 (4) | |||||||||

| Di Bello et al59 | Testosterone propionate | 300–500 | 10, 33 (3) | 12.3 (0.7) | — | 12.2 (0.4) | 11.6 (0.5) | — | 11.7 (0.4) |

| Methenolone enanthate | 300–600 | — | |||||||

| Testosterone cypionate | 200–350 | 10, 30 (7) | |||||||

| Dickerman et al15 | — | — | 8 | 11.27 (0.2)† | — | 8.74 (2.5) | 12.1 (1.0)† | — | 10.3 (2.0) |

| — | |||||||||

| 8 | |||||||||

| Hartgens et al63,|| | Nandrolone decanoate | 20–250 | 17, 32 (7) | 8.8 (1.1) | — | 8.3 (1.0) | 8.9 (0.7) | — | 8.6 (0.8) |

| Stanozolol | 30–140 | — | |||||||

| 15, 33 (5) | |||||||||

| Karila et al64,|| | — | 770 (310) | 16, 30 (5) | 11.2 (1.0)‡ | — | 8.9 (1.1) | 11.3 (1.1)‡ | — | 9.1 (1.0) |

| — | |||||||||

| 15, 26 (3) | |||||||||

| Krieg et al65,|| | — | 820 (620) | 36 (7) | 12 (1.5)† | — | 10.5 (1.0) | 10.5 (1.5) | — | 10 (0.5) |

| — | |||||||||

| 36 (11) | |||||||||

| Nieminen et al47,|| | Testosterone | 2,860¶ | 4, 30 (3) | 12.75 (1.5) | — | — | 13.75 (1.3) | — | — |

| Testosterone undecanoate | 2,660¶ | — | |||||||

| — | |||||||||

| Nottin et al67 | — | — | 6, 41 (6) | 10.8 (1.3) | — | 9.7 (1.7) | 10.0 (1.4) | — | 10.3 (0.9) |

| — | |||||||||

| 9, 38 (6) | |||||||||

| Palatini et al38,|| | Testosterone enanthate | 50–1,500 | 10, 27 (8) | 10.8 (2.3) | — | 9.6 (0.8) | 10.4 (2.3) | — | 10.1 (1.3) |

| and propionate | |||||||||

| Stanozolol | 50–150 | — | |||||||

| 14, 28 (5) | |||||||||

| Sachtleben et al70 | Stanozolol | — | 11, 27 (6) | 11.1 (1.2)* | — | 9.3 (1.2) | 11.2 (1.5)* | — | 9.5 (1.6) |

| Methandrostenolone nandrolone | — | ||||||||

| Testosterone cypionate | 13, 27 (6) | ||||||||

| Sader et al13 | Stanozolol | — | 10, 37 (3) | 10 (0.3)‡ | — | 8.7 (0.2) | 9/8 (0.4)† | — | 8.7 (0.3) |

| Nandrolone | — | ||||||||

| Creatine | 10, 34 (3) | ||||||||

| Thompson et al81,|| | Nandrolone decanoate | — | 12, 23 (4) | 10 (2.0) | — | 9.0 (1.0) | 8.0 (1.0) | — | 8 (1.0) |

| Testosterone cypionate | — | ||||||||

| Stanozolol | 11, 26 (7) | ||||||||

| Urhausen et al43,|| | — | 1,030 | 17, 31 (5) | 12.3 (1.4)§ | 11.5 (1.2)† | 10.3 (1.0) | 11.4 (1.3)*,§ | 10.2 (0.8) | 9.4 (1.5) |

| 15, 38 (7) | |||||||||

| 15, 28 (5) | |||||||||

| Urhausen et al71 | Methandione, stanozolol | 630 | 14, 28 (6) | 12.6 (1.7) | — | 11.6 (0.9) | 12.5 (1.2)‡ | — | 10.3 (1.8) |

| Testosterone depot | — | ||||||||

| 7, 26 (5) | |||||||||

| Zuliani et al44,|| | Testosterone enanthate and propionate | 750–1,500 | 6, 28 (2) | 11.8 (0.8) | — | 11.2 (0.7) | 10.8 (0.7) | — | 10.3 (0.5) |

| Human growth hormone | — | ||||||||

| 8, 26 (2) | |||||||||

Data are expressed as ranges, numbers, or mean ± SD. The control group included bodybuilders who denied AAS abuse.

p <0.05 versus ex-users;

p <0.05,

p <0.01, and

p <0.001 versus controls.

Other unspecified AAS abused.

Milligrams per international unit.

IVS = interventricular septum; PW = posterior wall.

In a retrospective case-control study, Krieg et al65 performed nonblinded echocardiographic measurements on 14 AAS users, 11 age-matched nonuser strength athletes, and 15 age-matched sedentary controls. Self-reported use of oral and injectable AAS was confirmed by luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone assay and elevated testosterone/epitestosterone ratios. AAS users had significantly enlarged interventricular septal wall thickness on echocardiography compared to nonusers and controls (p <0.05), although posterior wall thickness was only slightly larger. In contrast, Dickerman et al15 and others77 have reported that AAS abuse is associated with increased LV posterior wall and interventricular septal thickness compared to non-abusing athletes (Table 3). A variety of agents and doses were noted in the abusers. However, these studies are somewhat difficult to interpret, because most studies did not account for differences in exercise protocols, and most were not blinded.13,44,61,65,70

Several studies have confirmed that LVH may directly follow resistance training in the absence of AAS use.71,77–79 D’Andrea et al80 used nonblinded echocardiographic measurement to find that the thickness of the interventricular septum (12.3 ± 2.4 vs 9.7 ± 3.1 mm, p <0.01) and posterior LV wall (11.6 ± 1.6 vs 9.2 ± 2.1 mm, p <0.05) were greater in 130 strength-trained compared to 160 endurance-trained athletes. As always, however, an important caveat is the lack of control for occult AAS abuse.38,44,47,59,61–63,67,81

The few randomized clinical trials investigating the association between AAS use and LVH have similar limitations. Chung et al82 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which 30 healthy men were separated into 3 groups receiving weekly testosterone 200 mg, nandrolone decanoate 200 mg, or matching placebo injections for 4 weeks. After 4 weeks, blinded echocardiography showed that only the testosterone group had a significant increase in LV end-systolic diameter, although this remained within the normal range. In the only other randomized prospective study designed to evaluate the impact of AAS on cardiac dimensions, no changes were noted between strength athletes receiving 8 weeks of nandrolone at 200 mg/week compared to controls.63 There is a need for a closely monitored observational echocardiographic study over an extended period to compare cardiac morphology between AAS abusers and strength athletes, with appropriate control for occult AAS use.

Studies observing LVH related to AAS abuse reported that it likely reverses after discontinuing the agent, although with persistent effects for a prolonged period. In 1 study, echocardiography showed that LVH persisted for 9 ± 2 weeks after AAS withdrawal,62 although most AAS have half-lives <12 days.58 Although some investigators have suggested that concentric LVH may persist for years after discontinuing AAS,43 it is also possible that this observation reflects LVH secondary to strength training (or, again, potential occult AAS use).

AAS, acute MI, and sudden death

Alarming data have linked AAS with fatal events, although these are mostly case-control studies and case reports of acute coronary syndromes, MIs, and ventricular arrhythmias.24,46,83–88

In the absence of carefully conducted animal experiments, it is felt that AAS abuse may cause cardiac ischemia by exaggerating oxygen demand at peak exercise, potentially precipitated by accelerated atherosclerosis from lipoprotein abnormalities over years of abuse.89 As 1 potential direct mechanism, AAS also enhance platelet aggregation and thrombus formation by increasing platelet production of thromboxane A2 (a potent platelet aggregator), decreasing production of prostacyclin (prostaglandin I2, an inhibitor of platelet aggregation) and increasing fibrinogen levels.90 As stated previously, these detrimental effects must be weighed against the potentially beneficial effect of low-dose AAS on vasoreactivity.

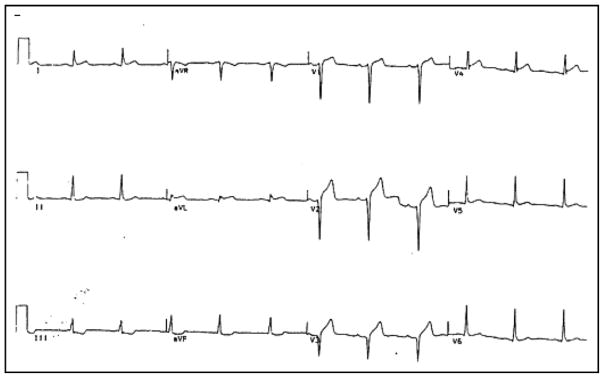

The relative clinical contributions of these mechanisms are unclear. Nevertheless, their combination may plausibly explain MIs or ventricular arrhythmias in young athletes with no cardiac risk factors,83,91 in many of whom AAS abuse has been ruled the primary cause of death.92–94 McNutt et al46 reported an acute MI in a 22-year-old bodybuilder who admitted to AAS abuse but lacked cardiac risk factors. The patient presented with markedly elevated LDL (596 mg/dl) and depressed HDL (14 mg/dl) yet had no family history of premature atherosclerosis or cardiac events. Within a month of discontinuing AAS, his LDL decreased to 220 mg/dl and his HDL increased to 35 mg/dl. Similar cases have been reported by others.69 Figure 1 shows the presenting electrocardiogram of a 25-year-old male athlete who abused nandrolone and presented with an acute MI without traditional cardiac risk factors. Acute angiography revealed extensive left anterior descending coronary artery thrombosis, which was managed by thrombolysis. Angiography in the subacute phase confirmed very mild luminal irregularity at the site of previous thrombosis.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram of a 25-year-old male athlete presenting with acute MI, showing anterior precordial Q waves and ST-segment elevation. The patient, who admitted to recent nandrolone abuse, had been previously healthy and without cardiac risk factors. Angiography revealed thrombosis in the left anterior descending coronary artery but no significant atherosclerotic narrowing. Reproduced from Recent Prog Horm Res.74

Finally, there are numerous anecdotes of potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias in AAS-abusers. The most commonly observed arrhythmias, typically occurring during physical exertion, include atrial fibrillation, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and supraventricular and ventricular ectopic beats.95 Hausmann et al84 describe a 23-year-old male bodybuilder who abused AAS and experienced sudden cardiac arrest. Postmortem examination revealed ventricular hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and acute MI, and the cause of death was attributed to arrhythmic sudden death secondary to AAS abuse. Dickerman et al96 reported a 20-year-old male bodybuilder who self-administered AAS 700 mg/week and had sudden cardiac arrest. Autopsy indicated LVH with a cardiac mass >2 times the upper limit of normal. More organized case series are needed to define to what extent such cases represent occult forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or other arrhythmogenic conditions.

Discussion

Limitations

This review included 1,467 subjects, but the major variables discussed included only a fraction of these subjects. Many studies that were reviewed were observational, cross-sectional studies with small sample sizes and single case reports that may explain variability in the reported data. Although prospective, randomized controlled studies would be ideal, such studies are also difficult to conduct because they must control for occult AAS use and recruit large samples of competitive athletes willing to disclose their (illegal) use of AAS. Many studies were not blinded, particularly with regard to blood pressure and echocardiographic assessment. Others did not account for variability in AAS dosage and cumulative duration of use or compared dissimilar exercise regimens (e.g., those that involve more resistance training can accentuate LVH). Many studies also did not specify the reasons for the discontinuation of AAS and whether such athletes continued exercising to the same degree. In addition, most studies followed AAS abusers for short periods, and many were too small to perform multivariate corrections for other risk factors.

Some studies on the adverse cardiometabolic effects of AAS may also reflect publication bias. Finally, AAS are often coabused with growth hormone, erythropoietin, and agents including creatine, ephedra alkaloids, and herbal supplements, although most AAS reports neither documented nor controlled for these agents. This is important because growth hormone may lead to cardiomyopathy, abnormal lipoprotein profiles,97,98 and LVH.64 Erythropoietin abuse is similarly linked to hypertension and increased risk for thromboembolic events.99 Such effects may be difficult to separate from the results of AAS abuse alone and motivate the need for more rigorous clinical screening. Nevertheless, AAS alter lipids, may affect LV dimensions, and have an unclear role in blood pressure elevation in athletes. Physicians should consider the possibility of AAS abuse when treating young athletes with abnormal lipids, LV dimensions, and potentially even blood pressure elevation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant HL83359 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, New York, New York, to Dr. Narayan.

References

- 1.Hoberman J, Yesalis CE. The history of synthetic testosterone. Sci Am. 1995;272:76–81. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0295-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saseen J, MacLaughlin EJ. Appetite stimulants and anabolic steroid therapy for AIDS wasting. AIDS Read. 1999;9:398, 401–402, 407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basaria S, Wahlstrom JT, Dobs AS. Clinical review 138: anabolic-androgenic steroid therapy in the treatment of chronic diseases. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2001;86:5108–5117. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.7983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denham B. Sports Illustrated, the mainstream press and the enactment of drug policy in major league baseball. Journalism. 2004;5:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Associated Press. [Accessed on June 1, 2010];Steroid, other drugs found in bodies of wrestler, wife, son. Available at: http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/news/story?id=2939837.

- 6.Clark A. Behavioral and physiological responses to anabolic-androgenic steroids. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:413–436. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson A, Evans NA. Anabolic androgenic steroids: a survey of 500 users. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2006;38:644–651. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210194.56834.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukas S. Current perspectives on anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90032-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. [Accessed on June 1, 2010];Title 21 United States Code (USC) Controlled Substances Act. Available at: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/21usc/844.htm.

- 10.Mitchell G. [Accessed on June 1, 2010];Report to the commissioner of baseball of an independent investigation into the illegal use of steroids and other performance enhancing substances by players in major league baseball. Available at: http://files.mlb.com/mitchrpt.pdf.

- 11.Maravelias C, Dona A, Stefanidou M, Spiliopoulou C. Adverse effects of anabolic steroids in athletes. A constant threat. Toxicol Lett. 2005;158:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutscher E, Lund BC, Perry PJ. Anabolic steroids: a review for the clinician. Sports Med. 2002;32:285–296. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sader MA, Griffiths KA, McCredie RJ, Handelsman DJ, Celermajer DS. Androgenic anabolic steroids and arterial structure and function in male bodybuilders. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:224–230. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenders JW, Demacker PN, Vos JA, Jansen PL, Hoitsma AJ, Van’t Laar A, Thien T. Deleterious effects of anabolic steroids on serum lipoproteins, blood pressure, and liver function in amateur bodybuilders. Int J Sports Med. 1988;9:19–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickerman R, Schaller F, Zachariah NY, McConathy WJ. Left ventricular size and function in elite bodybuilders using anabolic steroids. Clin J Sport Med. 1997;7:90–93. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199704000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesalis C, Kennedy NJ, Kopstein AN, Bahrke MS. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:1217–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henkin Y, Como JA, Oberman A. Secondary dyslipidemia. Inadvertent effects of drugs in clinical practice. JAMA. 1992;267:961–968. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.7.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood R. Anabolic steroids: a fatal attraction? J Neuroendrocrinol. 2006;18:227–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenehan P, Bellis M, McVeigh J. A study of anabolic steroid use in the North West of England. J Perf Enh Drugs. 1996;1:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricker R, Cook D. The incidence of anabolic steroid use among competitive bodybuilders. J Drug Educ. 1989;19:313–325. doi: 10.2190/EGT5-4YWD-QX15-FLKK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curry L, Wagman DF. Qualitative description of the prevalence and use of anabolic androgenic steroids by United States powerlifters. Percep Motor Skill. 1999;88:224–233. doi: 10.2466/pms.1999.88.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersson A, Garle M, Granath F, Thiblin I. Morbidity and mortality in patients testing positively for the presence of anabolic androgenic steroids in connection with receiving medical care. A controlled retrospective cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2006;81:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiblin I, Lindquist O, Rajs J. Cause and manner of death among users of anabolic androgenic steroids. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parssinen M, Kujala U, Vartiainen E, Sarna S, Seppala T. Increased premature mortality of competitive powerlifters suspected to have used anabolic agents. Int J Sports Med. 2000;21:225–227. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parssinen M, Seppala T. Steroid use and long-term health risks in former athletes. Sports Med. 2002;2002:83–84. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergink E, Geelen JAA, Turpijn EW. Metabolism and receptor binding of nandrolone and testosterone under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Acta Endocrinol. 1985;110:31–37. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.109s0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosano GM, Cornoldi A, Fini M. Effects of androgens on the cardiovascular system. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wynne F, Khalil RA. Testosterone and coronary vascular tone: implications in coronary artery disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:181–186. doi: 10.1007/BF03345150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrer M, Encabo A, Marin J, Balfagon G. Chronic treatment with anabolic steroid, nandrolone, inhibits vasodilator responses in rabbit aorta. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;252:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaugg M, Jamali NZ, Lucchinetti E, Xu W, Alam M, Shafiq SA, Siddiqui MA. Anabolic- androgenic steroids induce apoptotic cell death in adult rat ventricular myocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:90–95. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2001)9999:9999<00::AID-JCP1057>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kai H, Muraishi A, Sugiu Y, Nishi H, Seki Y, Kuwahara F, Kimura A, Kato H, Imaizumi T. Expression of proto-oncogenes and gene mutation of sarcomeric proteins in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1998;83:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.6.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieberherr M, Grosse B. Androgens increase intracellular calcium concentration and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol formation via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7217–7223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroemer G, Dallaporta B, Resche-Rigon M. The mitochondrial death/ life regulator in apoptosis and necrosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:619–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maron B, Roberts WC, McAllister HA, Rosing DR, Epstein SE. Sudden death in young athletes. Circulation. 1980;62:218–229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy C, Lawrence C. Anabolic steroid abuse and cardiac death. Med J Aust. 1993;158:346–348. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb121797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lajarin F, Zaragoza R, Tovar I, Martinez-Hernandez P. Evolution of serum lipids in two male bodybuilders using anabolic steroids. Clin Chem. 1996;42:970–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKillop G, Ballantyne D. Lipoprotein analysis in bodybuilders. Int J Cardiol. 1987;17:281–288. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(87)90077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palatini P, Giada F, Garavelli G, Sinisi F, Mario L, Michieletto M, Baldo-Enzi G. Cardiovascular effects of anabolic steroids in weight-trained subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:1132–1140. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldo-Enzi G, Giada F, Zuliani G, Baroni L, Vitale E, Enzi G, Magnanini P, Fellin R. Lipid and apoprotein modifications in body builders during and after self-administration of anabolic steroids. Metabolism. 1990;39:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90076-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fröhlich J, Kullmer T, Urhausen A, Bergmann R, Kindermann W. Lipid profile of body builders with and without self-administration of anabolic steroids. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1989;59:98–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02396586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartgens F, Rietjens G, Keizer HA, Kuipers H, Wolffenbuttel B. Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids on apolipoproteins and lipoprotein (a) Br J Sport Med. 2004;38:253–259. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lane H, Grace F, Smith JC, Morris K, Cockcroft J, Scanlon MF, Davies JS. Impaired vasoreactivity in bodybuilders using androgenic anabolic steroids. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:483–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urhausen A, Albers T, Kindermann W. Are the cardiac effects of anabolic steroid abuse in strength athletes reversible? Heart. 2004;90:496–501. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.015719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuliani U, Bernardini B, Catapano A, Campana M, Cerioli G, Spattini M. Effects of anabolic steroids, testosterone, and HGH on blood lipids and echocardiographic parameteres in body builders. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10:62–66. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glazer G. Atherogenic effects of anabolic steroids on serum lipid levels. A literature review. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1925–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNutt RA, Ferenchick GS, Kirlin PC, Hamlin NJ. Acute myocardial infarction in a 22-year-old world class weight lifter using anabolic steroids. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:164. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)91390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nieminen M, Ramo MP, Viitasalo M, Heikkila P, Karjalainen J, Mantysaari M, Heikkila J. Serious cardiovascular side effects of large doses of anabolic steroids in weight lifters. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:1576–1583. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeater R, Reed C, Ullrich I, Morise A, Borsch M. Resistance trained athletes using or not using anabolic steroids compared to runners: effects on cardiorespiratory variables, body composition, and plasma lipids. Br J Sport Med. 1996;30:11–14. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.30.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowman S. Anabolic steroids and infarction. BMJ. 1990;300:750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6726.750-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pope HJ, Katz DL. Psychiatric and medical effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid use. A controlled study of 160 athletes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labib M, Haddon A. The adverse effects of anabolic steroids on serum lipids. Ann Clin Biochem. 1996;33:263–264. doi: 10.1177/000456329603300316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Király C. Androgenic-anabolic steroid effects on serum and skin surface lipids, on red cells, and on liver enzymes. Int J Sports Med. 1988;9:249–252. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1025015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson P, Cullinane EM, Sady SP, Chenevert C, Saritelli AL, Sady MA, Herbert PN. Contrasting effects of testosterone and stanozolol on serum lipoprotein levels. JAMA. 1989;261:1165–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malarkey W, Strauss RH, Leizman DJ, Liggett M, Demers LM. Endocrine effects in female weight lifters who self-administer testosterone and anabolic steroids. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urhausen A, Torsten A, Wilfried K. Reversibility of the effects on blood cells, lipids, liver function and hormones in former anabolic-androgenic steroid abusers. J Steroid Biochem. 2003;84:369–375. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Connor JS, Baldini FD, Skinner JS, Einstein M. Blood chemistry of current and previous anabolic steroid users. Mil Med. 1990;155:72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hislop M, St Clair Gibson A, Lambert MI, Noakes TD, Marals AD. Effects of androgen manipulation on postprandial triglyceridaemia, low-density lipoprotein particle size and lipoprotein(a) in men. Atherosclerosis. 2001;159:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bagchus W, Smeets JM, Verheul HA, De Jager-Van Der Veen SM, Port A, Guert T. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of three different intramuscular doses of nandrolone decanoate: analysis of serum and urine samples in healthy men. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2005;90:2624–2630. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Di Bello V, Giorgi D, Bianchi M, Bertini A, Caputo MT, Valenti G, Furioso O, Alessandri L, Paterni M, Giusti C. Effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids on weight-lifters’ myocardium: an ultrasonic videodensitometric study. Med Sci Sport Exer. 1999;31:514–521. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riebe D, Fernhall B, Thompson PD. The blood pressure response to exercise in anabolic steroid users. Med Sci Sport Exer. 1992;24:633–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D’Andrea A, Caso P, Salerno G, Scarafile R, De Corato G, Mita C, Di Salvo G, Severino S, Cuomo S, Liccardo B, Esposito N, Calabro R. Left ventricular early myocardial dysfunction after chronic abuse of anabolic androgenic steroids: a Doppler myocardial and strain imaging analysis. Br J Sport Med. 2006;41:149–155. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Piccoli B, Giada F, Benettin A, Sartori F, Piccolo E. Anabolic steroid use in body builders: an echocardiographic study of left ventricle morphology and function. Int J Sports Med. 1991;12:408–412. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hartgens F, Cheriex EC, Kuipers H. Prospective echocardiographic assessment of anabolic steroids effects on cardiac structure and function in strength athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2003;24:344–351. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karila T, Karjalainen JE, Mantysaari MJ, Viitasalo MT, Seppala TA. Anabolic androgenic steroids produce dose-dependent increase in left ventricular mass in power athletes, and this effect is potentiated by concomitant use of growth hormone. Int J Sports Med. 2003;24:337–343. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krieg A, Scharhag J, Albers T, Kindermann W, Urhausen A. Cardiac tissue Doppler in steroid users. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28:638–643. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-964848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuipers H, Wijnen JA, Hartgens F, Willems SM. Influence of anabolic steroids on body composition, blood pressure, lipid profile and liver functions in body builders. Int J Sports Med. 1991;12:413–418. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nottin S, Nguyen LD, Terbah M, Obert P. Cardiovascular effects of androgenic anabolic steroids in male bodybuilders determined by tissue Doppler imaging. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:912–915. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mottram D, George AJ. Anabolic steroids. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;14:55–69. doi: 10.1053/beem.2000.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kennedy C. Myocardial infarction in association with misuse of anabolic steroids. Ulster Med J. 1993;62:174–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sachtleben T, Berg KE, Elias BA, Cheatham JP, Felix GL, Hofschire PJ. The effects of anabolic steroids on myocardial structure and cardiovascular fitness. Med Sci Sport Exer. 1993;25:1240–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Urhausen A, Holpes R, Kindermann W. One- and two-dimensional echocardiography in bodybuilders using anabolic steroids. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1989;58:633–640. doi: 10.1007/BF00418510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharma S. Athlete’s heart—effect of age, sex, ethnicity and sporting discipline. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:665–669. doi: 10.1113/eph8802624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marsh J, Lehmann MH, Ritchie RH, Gwathmey JK, Green GE, Schiebinger RJ. Androgen receptors mediate hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 1998;98:256–261. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuhn C. Anabolic steroids. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:411–434. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu P, Death AK, Handelsman DJ. Androgens and cardiovascular disease. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:313–340. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Payne J, Kotwinski PJ, Montgomery HE. Cardiac effects of anabolic steroids. Heart. 2004;90:473–475. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.025783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dickerman R, Schaller F, McConathy WJ. Left ventricular wall thickening does occur in elite power athletes with or without anabolic steroid use. Cardiology. 1998;90:145–148. doi: 10.1159/000006834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fisher AG, Adams TD, Yanowitz FG, Ridges JD, Orsmond G, Nelson AG. Noninvasive evaluation of world class athletes engaged in different modes of training. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:337–341. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Colan S, Sanders SP, Borow KM. Physiologic hypertrophy: effects on left ventricular systolic mechanics in athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:776–783. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.D’Andrea A, Limongelli G, Caso P, Sarubbi B, Peitra AD, Brancaccio P, Cice G, Scherillo M, Limongelli F, Calabro R. Association between left ventricular structure and cardiac performance during effort in two morphological forms of athlete’s heart. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thompson F, Sadaniantz A, Cullinane EM, Bodziony KS, Catlin DH, Torek-Both G, Douglas PS. Left ventricular function is not impaired in weight lifters who use anabolic steroids. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:278–282. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chung T, Kelleher S, Liu PY, Conway AJ, Kritharides L, Handelsman DJ. Effects of testosterone and nandrolone on cardiac function: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;66:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kennedy M, Corrigan AB, Pilbeam ST. Myocardial infarction and cerebral haemorrhage in a young body builder taking anabolic steroids. Aust N Z J Med. 1993;23:713. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb04734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hausmann R, Hammer S, Betz P. Performance enhancing drugs (doping agents) and sudden death—a case report and review of the literature. Int J Legal Med. 1998;111:261–264. doi: 10.1007/s004140050165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Luke J, Farb A, Virmani R, Sample RH. Sudden cardiac death during exercise in a weight lifter using anabolic androgenic steroids: pathological and toxicological findings. J Forensic Sci. 1990;35:1441–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Angelilli A, Katz ES, Goldenberg RM. Cardiac arrest following anaesthetic induction in a world-class bodybuilder. Acta Cardiol. 2005;60:443–444. doi: 10.2143/AC.60.4.2004995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wysoczanski M, Rachko M, Bergmann S. Acute myocardial infarction in a young man using anabolic steroids. Angiology. 2008;59:376–378. doi: 10.1177/0003319707304883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fineschi V, Riezzo I, Centini F, Silingardi E, Licata M, Beduschi G, Karch SB. Sudden cardiac death during anabolic steroid abuse: morphologic and toxicologic findings in two fatal cases of bodybuilders. Int J Legal Med. 2007;121:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s00414-005-0055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sullivan ML, Martinez CM, Gennis P, Gallagher EJ. The cardiac toxicity of anabolic steroids. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1998;41:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(98)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ferenchick G. Anabolic/androgenic steroid abuse and thrombosis: is there a connection? Med Hypotheses. 1991;35:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(91)90079-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roeggia M, Heinz G, Werba E, Roeggla G. Cardiac tamponade in a 21-year-old body builder with anabolica abuse. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:411–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferenchick G, Adelman S. Myocardial infarction associated with anabolic steroid use in a previously healthy 37-year-old weight lifter. Am Heart J. 1992;124:507–508. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90620-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huie M. An acute myocardial infarction occurring in an anabolic steroid user. Med Sci Sport Exer. 1994;26:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fisher M, Appleby M, Rittoo D, Cotter L. Myocardial infarction with extensive intracoronary thrombus induced by anabolic steroids. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:222–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Furlanello F, Serdoz LV, Cappato R, De Ambroggi L. Illicit drugs and cardiac arrhythmias in athletes. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:487–494. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280ecfe3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dickerman RD, Schaller F, Prather I, McConathy WJ. Sudden cardiac death in a 20-year-old bodybuilder using anabolic steroids. Cardiology. 1995;86:172–173. doi: 10.1159/000176867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Saugy M, Robinson N, Saudan C, Baume N, Avois L, Mangin P. Human growth hormone doping in sport. Br J Sport Med. 2006;40:i35–i39. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jenkins P. Growth hormone and exercise. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:683–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jenkins P. Doping in sport. Lancet. 2002;360:99–100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]