Abstract

Fungi of the CTG clade translate the Leu CUG codon as Ser. This genetic code alteration is the only eukaryotic sense-to-sense codon reassignment known to date, is mediated by an ambiguous serine tRNA (tRNACAGSer), exposes unanticipated flexibility of the genetic code and raises major questions about its selection and fixation in this fungal lineage. In particular, the origin of the tRNACAGSer and the evolutionary mechanism of CUG reassignment from Leu to Ser remain poorly understood. In this study, we have traced the origin of the tDNACAGSer gene and studied critical mutations in the tRNACAGSer anticodon-loop that modulated CUG reassignment. Our data show that the tRNACAGSer emerged from insertion of an adenosine in the middle position of the 5′-CGA-3′anticodon of a tRNACGASer ancestor, producing the 5′-CAG-3′ anticodon of the tRNACAGSer, without altering its aminoacylation properties. This mutation initiated CUG reassignment while two additional mutations in the anticodon-loop resolved a structural conflict produced by incorporation of the Leu 5′-CAG-3′anticodon in the anticodon-arm of a tRNASer. Expression of the mutant tRNACAGSer in yeast showed that it cannot be expressed at physiological levels and we postulate that such downregulation was essential to maintain Ser misincorporation at sub-lethal levels during the initial stages of CUG reassignment. We demonstrate here that such low level CUG ambiguity is advantageous in specific ecological niches and we propose that misreading tRNAs are targeted for degradation by an unidentified tRNA quality control pathway.

Keywords: CTG clade, Candida albicans, tRNA, CUG codon, evolution, genetic code

Introduction

The genetic code is viewed as frozen and universal.1 However 20 codon reassignments have been discovered in diverse bacterial and eukaryotic species, indicating that the code evolves.2 These alterations involve both nonsense and sense codons, but, with exception of the fungal CTG clade, eukaryotic nuclear sense codons are not reassigned.2,3 Mitochondria are particularly interesting because they reassigned both nonsense and sense codons in multiple phylogenetic lineages and the reassignment patterns indicate that codons starting with A or U are more prone to reassignment than those starting with C or G. In other words, the strength of the first codon-anticodon base pair is fundamental to the evolution of genetic code alterations.2 Beyond this, the molecular pathways of codon reassignment are poorly understood and difficult to rationalize due to proteome disruption and negative impact on fitness.

A remarkable genetic code alteration occurs in the fungal CTG clade where the CUG codon is reassigned from Leu to Ser.4-6 Surprisingly, proteome-wide incorporation of both Ser (97%) and Leu (3%) at CUG sites still occurs in most CTG clade species due to dual recognition of the tRNACAGSer by the Seryl- and the Leucyl-tRNA synthetases (SerRS and LeuRS).7,8 The distinct chemical properties of Leu (hydrophobic, located in the hydrophobic core of proteins) and Ser (polar, located on protein surfaces), suggest that this genetic code alteration should have generated massive disruption of the proteome of the CTG clade ancestor, raising the question of how did these fungi survive such extreme genetic chaos. An important finding from comparative genome analysis of fungal species is that the negative pressure produced by incorporation of both Ser and Leu at CUGs erased all CUGs from the genome of the CTG clade ancestor, eliminating the toxicity of CUG ambiguity altogether.4,9 Indeed, the CUGs present in extant CTG clade species re-emerged recently from single and double simultaneous mutations of codons coding for Ser or amino acids with similar chemical properties. In other words, the CUGs re-emerged in presence of ambiguity and only those CUG protein sites that tolerate insertion of both Ser and Leu were selected,4,9 as demonstrated by X-Ray chrystalography and molecular modeling of C. albicans proteins.10 We are left, therefore, with three major evolutionary questions, namely how did the tRNACAGSer appear, which is its evolutionary pathway and why was it not eliminated by natural selection?

Previous in silico studies suggested that the mutant tRNACAGSer that decodes the CUG codon as Ser emerged 272 ± 25 million y ago, prior to the Saccharomyces and Candida split (170 ± 27 million y ago) from a tRNASer.9 Therefore, the tRNACAGSer is a typical tRNASer, but contains a Leu 5′-CAG-3′anticodon. It also has m1G at position 37 (m1G37) in the anticodon-loop, which is typical of tRNALeu and is not present in tRNASer. This methylated guanosine is functionally very important as it improves decoding accuracy by preventing frameshifting and is also a leucylation identity determinant.11 Another remarkable structural feature of the tRNACAGSer is the presence of guanosine at position 33 (G33). In general, tRNAs have a highly conserved uridine at position 33 (U33), which is critical for the correct U-turn of the anticodon-loop and for stacking of the anticodon bases.12 It is still unclear how the phosphate backbone of the tRNACAGSer turns and maintains correct stacking of the anticodon bases with G33, however structural probing data show that G33 distorts the top of the anticodon-stem of the tRNACAGSer and prevents efficient leucylation of the tRNA by the LeuRS.11,13 These data suggest that a minimal set of mutations in the anticodon-loop of the tRNACAGSer played critical roles in the evolution of CUG reassignment.14

To better understand the role of those anticodon-loop mutations, we have reconstructed in vivo the early steps of the evolutionary pathway of the tRNACAGSer. For this, we have used molecular phylogeny of a large set of tRNA sequences produced by fungal genome sequencing initiatives and traced the origin of the tRNACAGSer at the isoacceptor level. We then engineered yeast strains that recapitulate the critical steps of CUG reassignment.9,15 Our data show that expression of the mutant tRNACAGSer is strongly repressed by an unidentified tRNA quality control pathway and that the G33 and m1G37 mutations fine tune the decoding efficiency of the tRNACAGSer. We postulate that such tRNACAGSer downregulation was essential to ensure cell viability during the initial stages of CUG reassignment. We further show that selection of the tRNACAGSer was possible because low level Ser misincorporation into proteins produces adaptive phenotypes in specific ecological niches.

Results

Model system of CUG reassignment

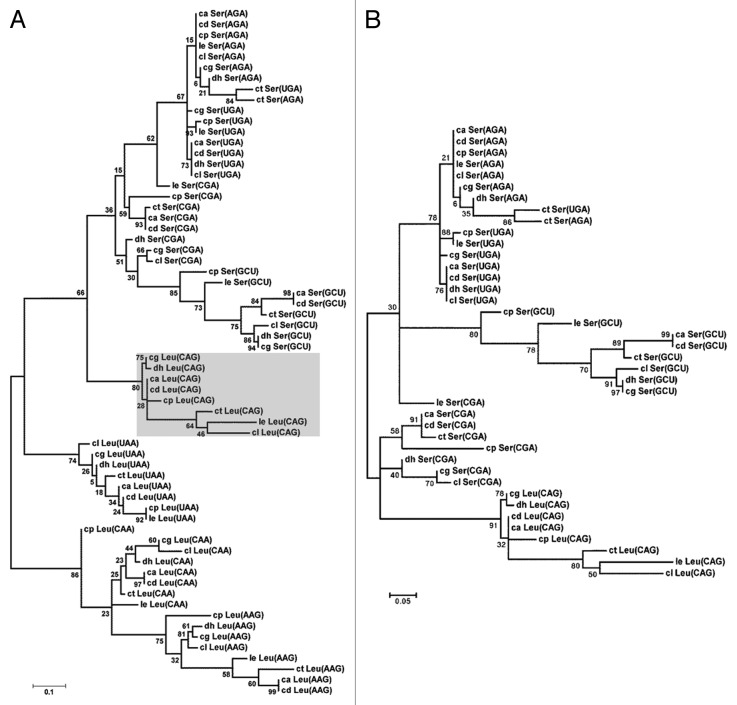

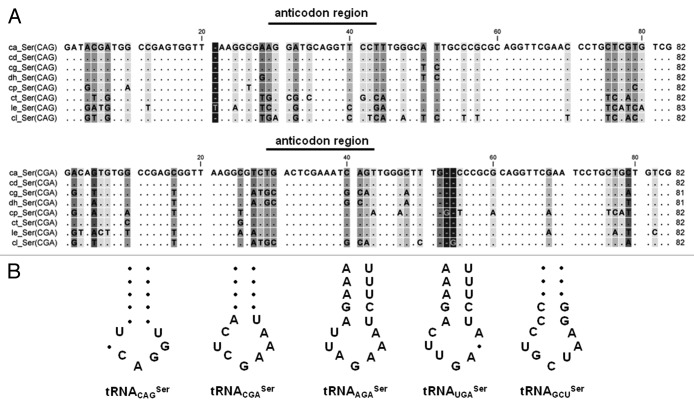

To reconstruct the tRNACAGSer evolutionary pathway, we have traced the origin of the ancestral tRNASer by aligning the sequences of the Leu and Ser tRNAs of the fungal CTG clade species. This clade includes Candida albicans (ca), Candida dubliniensis (cd), Candida tropicalis (ct), Candida parapsilosis (cp), Lloderomyces elongisporus (le), Candida guilliermondii (cg), Debaryomyces hansenii (dh) and Candida lusitaniae (cl), whose genomes have been sequenced recently.4 A phylogenetic tree built using the maximum likelihood method (Fig. 1A) showed that the tRNACAGSer forms a branch of tRNASer rather than tRNALeu and is more closely related with the tRNACGASer than with the other tRNASer (Fig. 1B). The multiple sequence alignment of tRNACAGSer sequences of the CTG clade species showed high variability in the tRNACAGSer anticodon-stem domain (Fig. 2A), which was surprising considering the semi-conserved structural match between the anticodon-loop and the anticodon-stem in tRNA isodecoders. This match modulates the efficiency of codon decoding.16 This atypical nucleotide variability of the anticodon-arm of the tRNACAGSer therefore provides evidence for rapid evolution of the tRNA anticodon-arm to accommodate the instability produced by the 5′-CAG-3′ sequence in the anticodon-loop of the tRNACGASer ancestor. Interestingly, anticodon-arm sequence variability was also observed in tRNACGASer and tRNAGCUSer, suggesting that these tRNAs are also evolving faster than the other tRNASer (Fig. 2B).

Figure 1. Phylogeny of Ser and Leu tRNAs of the CTG clade species. (A) The phylogenetic analysis of Ser and Leu tRNAs from the CTG clade species was constructed using a maximum likelihood method, which separated the tRNAs in Leu and Ser groups. (B) The tRNACAGSer aligned closer to the tRNACGASer, suggesting that it evolved from the tRNACGASer ancestor. The tRNAs analyzed belong to Candida albicans (ca), Candida dubliniensis (cd), Candida tropicalis (ct), Candida parapsilosis (cp), Lloderomyces elongisporus (le), Candida guilliermondii (cg), Debaryomyces hansenii (dh) and Candida lusitaniae (cl). Bootstrap values for all nodes are displayed. The phylogenetic analysis was performed with Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis (MEGA5) software and tRNA sequences were retrieved from the Candida Gene Order Browser.

Figure 2. Variability of anticodon sequences of tRNAs from CTG clade. (A) The aligned tRNACAGSer and tRNACGASer sequences from the CTG clade species showed high variability in the anticodon region. (B) Sequence of anticodon arm of tRNASer from CTG clade species showing higher variability in the anticodon-stem of tRNACAGSer and tRNACGASer, the other tRNAs have more conserved anticodon-stems. The indicated nucleotides are conserved while filled circles correspond to sequence variation. CTG clade species analyzed include Candida albicans (ca), Candida dubliniensis (cd), Candida tropicalis (ct), Candida parapsilosis (cp), Lloderomyces elongisporus (le), Candida guilliermondii (cg), Debaryomyces hansenii (dh) and Candida lusitaniae (cl). Multiple tRNA sequence alignments were performed with CLC sequence viewer 6 software and tRNA sequences from CTG clade species were obtained with Candida Gene Order Browser.

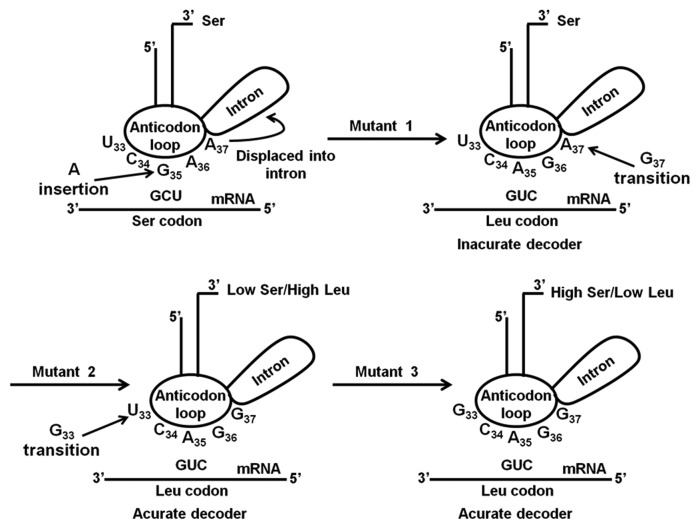

Beyond the nucleotides N33, N35 and N37 in the anticodon-loop and the nucleotide variability identified in the anticodon-stem, the tRNACAGSer has a typical structure of tRNASer isoacceptors, suggesting that most of the evolutionary changes of the tRNACAGSer occurred in its anticodon-arm, with mutations G33, A35 and G37 playing the major roles in CUG reassignment. To clarify this hypothesis, we have re-introduced these mutations in the C. albicans tRNACGASer (Fig. 3) by site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) and reconstructed each step of the CUG reassignment pathway in yeast. The serylation efficiency of these mutant tRNAs was determined in vitro and their decoding efficiency was determined in vivo by evaluating the impact of Ser misincorporation at Leu-CUG codons on yeast fitness.

Figure 3. Putative evolutionary pathway of the Candida albicans tRNACAGSer. In silico studies suggested that insertion of an adenosine in the middle position of the anticodon of a tRNACGASer gene transformed the 5′-CGA-3′ into a 5′-CAG-3′ anticodon, originating the Ser tRNA mutant 1, which is capable of decoding Leu CUG as Ser. Decoding accuracy and efficiency requires two other mutations, namely G37 (mutant 2) and G33 (mutant 3). The second mutation permitted the recognition of the tRNACAGSer by the LeuRS in addition to its cognate SerRS, which introduced ambiguity at CUG codons, while the third mutation lowered leucylation efficiency of the tRNACAGSer.

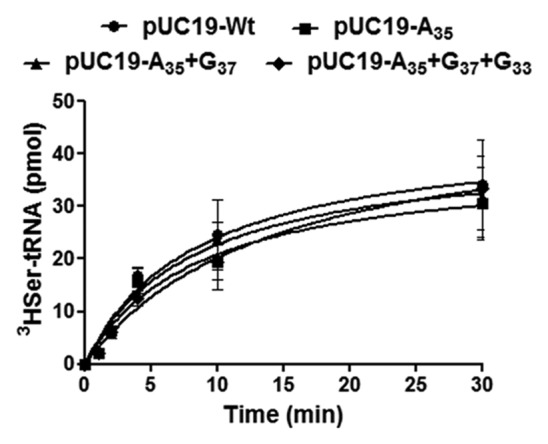

Serylation of the tRNACAGSer played a neutral role in CUG reassignment

Since the C. albicans SerRS recognizes the extra-arm and the acceptor stem of the tRNASer and does not contact the anticodon-arm,17-21 significant alterations in serylation efficiency of the mutant tRNACGASer were not expected (Fig. 3). However, small effects on serylation could not be excluded due to the distortion induced by G33 in the anticodon-stem.11,13 To clarify this issue, the mutant tRNAs were transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase and were aminoacylated using recombinant C. albicans SerRS expressed and purified from E. coli. The aminoacylation efficiency of the mutant tRNAs (A35, A35+G37 and A35+G37+G33) was similar to the wild-type control tRNA (WT) (Fig. 4), confirming that mutations in the anticodon loop of tRNACGASer did not affect SerRS recognition and aminoacylation, at least in vitro.

Figure 4. Mutations in the anticodon loop of the tRNACAGSer do not affect serylation. In vitro aminoacylation assays were performed with in vitro synthesized wild-type (pUC19-WT) and the mutant tRNACGASer, A35 (pUC19-A35), A35+G37 (pUC19-A35+G37) and A35+G37+G33 (pUC19-A35+G37+G33). Aminoacylation reactions were performed using purified C. albicans SerRS overexpressed in E. coli. Data represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

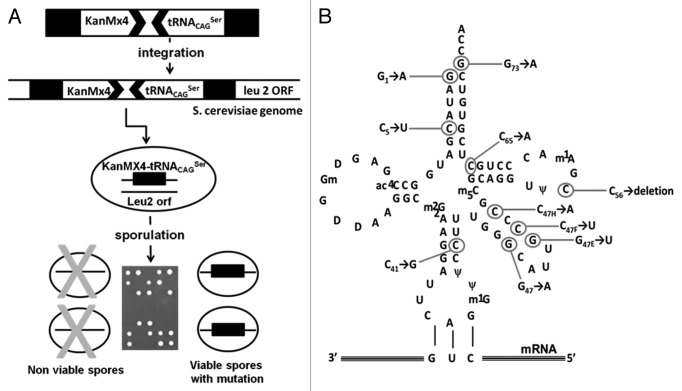

We have further confirmed the neutrality of the anticodon-arm mutations on serylation of the tRNACAGSer using an in vivo-forced evolution strategy. We have hypothesized that the destabilization of the proteome of haploid S. cerevisiae cells by Ser misincorporation at CUGs would decrease fitness, allowing for selection of mutations that abolished serylation of the tRNACAGSer or increased its turnover rate. Mapping such mutations on the structure of the tRNACAGSer should permit identifying serylation identity determinants. To test this hypothesis, the tDNACAGSer gene was integrated into the genome of diploid yeast cells using the KanMx4 gene integration cassette (Fig. 5A). The recombinant diploid cells were then sporulated, tetrads were dissected and spores were allowed to grow in media containing geneticin to select viable haploid spores containing the KanMx4 cassette and the tRNACAGSer gene (Fig. 5A). Since Ser misincorporation is lethal in certain haploid backgrounds,14 spore viability in selective media was entirely dependent on mutations that inactivated the tRNACAGSer (Fig. 5A). Such inactivating mutations were identified by PCR amplification of the tRNACAGSer gene, followed by Sanger sequencing. Each of the viable spores screened contained at least one mutation in the tDNACAGSer gene, which accumulated in the extra-arm and acceptor-stem of the tRNACAGSer (Fig. 5B). Since these structural domains contain the known identity determinants of eukaryotic tRNASer,17,18,20,22 the data support the hypothesis that viability was sustained by inhibition of tRNACAGSer serylation. However, some mutations accumulated in the TΨC-arm and one was detected in the anticodon-stem, which are not known to interact with the SerRS. But, these mutant tRNASer were not detected by northern blot (Fig. S1A) and cells expressing them had identical growth rate to control cells (not expressing tRNACAGSer) (Fig. S1B). In vitro aminoacylation of these mutant tRNAs with purified SerRS showed sharp decrease in serylation levels (Fig. S2A and B). Altogether, these data suggested that the mutations affected both tRNA stability and serylation. More importantly, the lack of inactivating mutations in the anticodon-loop supported our hypothesis that mutational alteration of the anticodon-loop of the tRNACAGSer did not impact on the serylation of the tRNACAGSer. In other words, the CUG reassignment was driven by a small number of mutations in the anticodon-arm of the tRNACAGSer ancestor that had minor impact on its serylation efficiency.

Figure 5. In vivo forced evolution methodology used to identify mutations that inactivate the C. albicans tRNACAGSer. (A) In vivo forced evolution was used to screen for mutations that affect the C. albicans tRNACAGSer stability and identity. This method was based on PCR amplification of the DNA cassette containing the tRNACAGSer fused to the KanMx4 gene and subsequent integration by homologous recombination into the LEU2 locus of diploid yeast cells. Yeast containing the tRNACAGSer gene integrated in the genome were sporulated and tetrades were dissected using a micromanipulator. The tRNACAGSer gene was amplified from viable spores by PCR and the amplified DNA was sequenced. (B) The in vivo forced evolution strategy using the tRNACAGSer gene expressed in yeast cells identified 10 different mutations. Most mutations localized in the acceptor-stem and variable-arm.

Expression and in vivo charging of the misreading tRNACAGSer

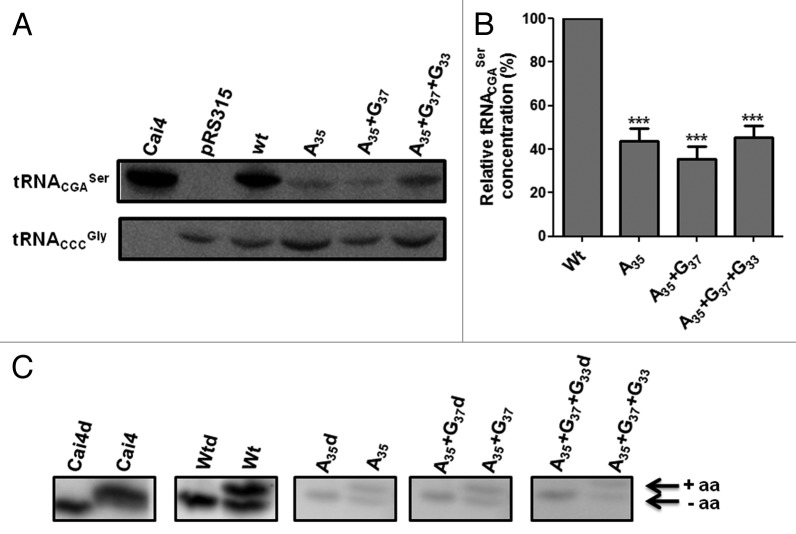

To determine the effect of the anticodon-loop mutations (A35, A35+G37 and A35+G37+G33) on the cellular activity of the tRNACGASer, the WT tDNACGASer gene with its flanking regions (150 bp fragment) was amplified by PCR from C. albicans gDNA and was cloned into the yeast pRS315 single-copy vector. This allowed for single-copy expression of the tRNACGASer in yeast. The same construct was then used to introduce the single A35, double A35+G37 and triple A35+G37+G33 mutations into the tDNACGASer for single-copy expression. Since the WT and mutant tRNAs were expressed from the same vector and the same tDNA fragment, the effect of each mutation on the cellular abundance of the tRNACAGSer could be determined using comparative northern blot analysis. The electrophoretic mobility of the WT tRNACGASer and mutant tRNACAGSer expressed in yeast was similar to that of the WT tRNACGASer expressed in C. albicans, indicating the mutant tRNACAGSer were correctly processed and expressed in yeast (Fig. 6A). Similar expression levels of the WT tRNACGASer were observed in C. albicans and yeast, showing that yeast expresses C. albicans tRNAs as expected (Fig. 6A). However, the single A35, double A35+G37 and triple A35+G37+G33 mutations reduced the cellular abundance of the mutant tRNAs by 57%, 65% and 55%, respectively (Fig. 6A and B), indicating that the anticodon-loop mutations destabilized and likely targeted the mutant tRNACAGSer for degradation. Similar results were observed for multi-copy expression of the mutant tRNAs, indicating that increased gene copy number did not increase expression (Fig. S3). We cannot exclude the possibility that transcriptional downregulation may have occurred; however, this is unlikely because the tDNA gene promoters are intragenic23 and the expression of the WT tRNA was not affected, nor was the expression of the control tRNACCCGly that was used as internal control for data normalization (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. The mutants tRNACAGSer are expressed at low level in yeast. (A) To check the in vivo expression of the WT tRNACGASer and mutant tRNACGASer in yeast, 50 µg of total tRNA were extracted and purified under acidic conditions and were fractionated on 15% polyacrylamide gels containing 8M urea at room temperature. tRNACGASer and tRNACCCGly were detected using ɣ-32P-ATP-tDNACGASer and ɣ-32P-ATP-tDNACCCGly probes. Cai4 corresponds to total tRNA purified from C. albicans. Membranes were exposed for 24 h to a K-screen and were visualized using a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX. (B) Quantification of expression of the mutant tRNAs relative to the WT tRNA. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments (***p < 0.001, one-way Anova post Bonferroni’s test with CI 95% relative to Wt tRNACGASer). (C) In vivo aminoacylation of the WT and mutant tRNACGASer in yeast. In vivo aminoacylation of WT and mutant tRNACGASer was evaluated using acidic northern blot analysis. In vitro deacylated and in vivo acylated tRNAs were fractionated on 6.5% polyacrylamide gels containing 8M urea at 4°C, using 10 mM sodium acetate (pH = 4.5) buffer. The tRNACGASer was detected using ɣ-32P-ATP-tRNACGASer probe. CaI4 corresponds to tRNA extracted from C. albicans. Membranes were exposed for 24 h to a K-screen and were visualized using the Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX.

To test whether the various mutant tRNACGASer were charged in vivo, total tRNA samples were extracted from yeast under acidic conditions (see Materials and Methods) and were fractionated on an acidic 6.5% polyacrylamyde gel containing 8M urea, which separates charged from uncharged tRNA.24 These tRNAs were then transferred to a hybond-N membrane and were subjected to northern blot analysis. In vitro deacylated tRNAs were used as internal controls. As expected, the WT C. albicans tRNACGASer was fully charged in C. albicans CaI4 cells; however, ~45% of this WT tRNA was not charged in yeast (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the serylation systems of both fungi are not identical. Similar results were obtained for all three mutant tRNACAGSer (Fig. 6C). These gels further confirmed the low expression levels of the mutant tRNAs, showing that the anticodon-loop mutations affected mainly their expression with little impact on relative levels of serylation.

The impact of CUG reassignment on protein stability and yeast fitness

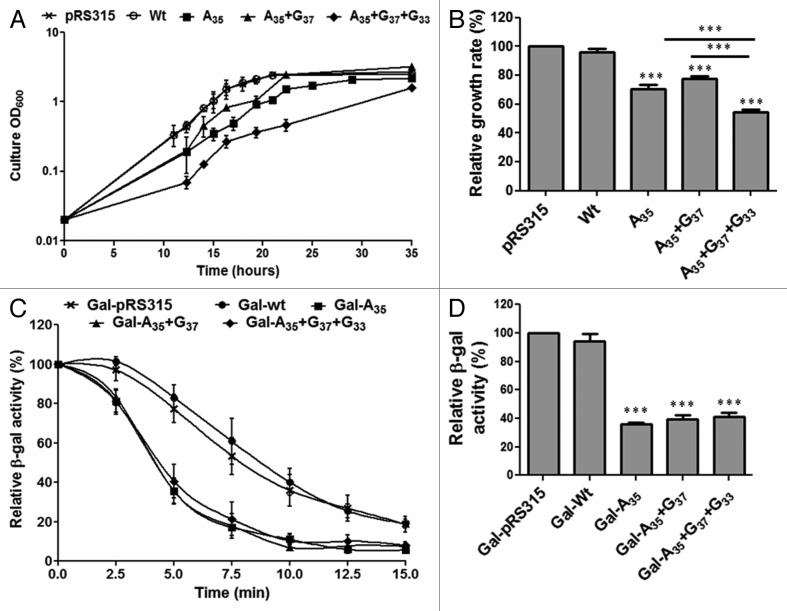

Proteome-wide Ser misincorporation at Leu-CUG sites by the WT C. albicans tRNACAGSer is toxic and even lethal in certain yeast genetic backgrounds.14,25 We have used the fitness cost of this toxicity as an in vivo proxy of the decoding efficiency of the mutant tRNACAGSer. Expression of the A35 mutant decreased growth rate by 30% while the double mutant decreased it by 23% (Fig. 7A and B). The slightly smaller relative growth rate decrease of the A35+G37 is likely associated with the fact that G37 is a leucylation identity determinant, i.e., the LeuRS recognizes A35 and m1G37,26 competes with the SerRS for the tRNACAGSer and produces Leu-tRNACAGSer that incorporates Leu at CUG codons,11 reducing slightly Ser misincorporation levels and toxicity. The G33 mutation (triple mutant A35+G37+G33) decreased growth rate by 46% (Fig. 7B), suggesting that this mutation improves decoding efficiency of the tRNA (higher level of Ser misincorporation). This is due to the combined increase in expression of the triple mutant relative the double mutant (Fig. 6B) and the negative effect of the G33 mutation on leucylation of the tRNACGASer (G33 is a leucylation antideterminant).11

Figure 7. Effect of CUG reassignment on yeast fitness. (A) Partial CUG reassignment had a strong negative impact on yeast growth rate. Yeast cell cultures transformed with WT and mutant C. albicans tRNACGASer were inoculated at an initial OD600 of 0.02 and were grown in selective medium at 30°C, 180 rpm, until they reached stationary phase. (B) The relative growth rate of cells transformed with WT and mutant tRNACGASer was determined using exponential growth phase values, relative to the control cells. (C) To determine the effect of Ser misincorporation on protein structure E. coli β-gal was co-expressed with WT tRNACGASer and mutant tRNACGASer in yeast cells. Thermoinactivation profiles were determined by measuring β-gal activity after a denaturation step at 47°C. The β-gal activity that remained functional after thermal inactivation was measured by incubating cells at 30°C for 2 min with ONPG. β-gal activity at each time point corresponds to the % of activity relative to total activity measured in cells prior to denaturation. (D) β-gal activity was quantified after incubating total cell protein extracts at 30°C with ONPG until a pale yellow color appeared. Reactions were stopped with addition of 1M sodium carbonate. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates of three independent clones. (***p < 0.001 for one-way Anova post Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test with CI 95%, relative to pRS315).

The above data indicate that the A35 initial mutation produced a functional tRNASer that could misincorporate Ser at Leu-CUG codons. This tRNA destabilized the proteome and decreased yeast fitness. It also showed that the G37 mutation had a secondary impact on fitness relative to the critical A35 mutation, while the G33 mutation likely improved Ser misincorporation levels significantly. To better clarify the role of the latter mutations on CUG reassignment, we have used a β-galactosidase (β-gal) thermostability assay14 as readout for Ser misincorporation efficiency. The E. coli LacZ gene contains 54 CUG codons, making β-gal a sensitive reporter of Ser misincorporation at CUGs in vivo.14 Yeast cells expressing the empty plasmid (pRS315), the WT tRNACGASer or one of the three mutant tRNACAGSer, were co-transformed with the pGL-C1 plasmid, which encodes a fusion between glutathione S-transferase (GST) and β-galactosidase genes (GST-β-gal).14 The thermal inactivation profiles of β-gal produced in presence of both controls (tRNACGASer and empty pRS315 vector) were similar (Fig. 7C), indicating that the C. albicans WT tRNACGASer is an authentic Ser decoder in yeast. However, thermal stability of β-gal produced in presence of the mutant tRNACAGSer decreased by 40% (Fig. 7C). Total β-gal activity was in line with β-gal thermal stability (Fig. 7D) as cells expressing A35, A35+G37 and A35+G37+G33 tRNAs showed relative decrease of 65%, 60% and 58% of β-gal activity. There was a small difference between the single, double and triple mutants, suggesting that decoding efficiency of the three tRNAs was similar (Fig. 7D).

Selective advantages introduced by proteome-wide Ser misincorporation

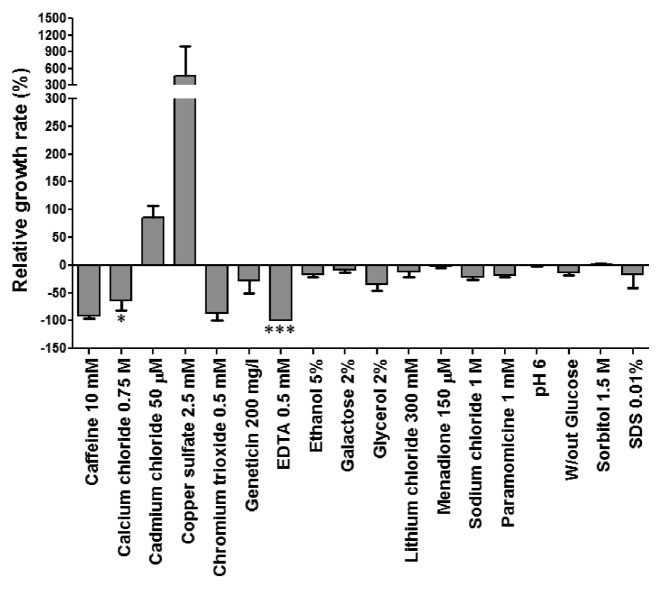

The negative impact of the anticodon mutations on yeast fitness is a strong hurdle to explaining the evolution of the CTG clade genetic code alteration since such evolution needs to be rationalized under negative selective pressure. It is simply not possible to explain how the tRNACAGSer was selected. We have shown previously that mistranslation can have mild positive outcomes under specific growth conditions and we postulated that CUG reassignment may have evolved under specific conditions were mistranslation produces adaptive phenotypes.27 Here we extend those initial studies using a phenotypic array probing 18 growth conditions, which included different nutrients and stressors, namely medium without glucose, 2% galactose, 2% glycerol, acidity, caffeine, ethanol, sorbitol, SDS, cadmium, copper, chromium, lithium, geneticin, paramomycin, menadione, EDTA, calcium and sodium chloride. The data showed that Ser misincorporation at CUG codons had mainly negative outcomes; however, near-neutral and positive outcomes were visible in some cases (Fig. 8). For example, there was a strong growth advantage (500%) of the cells expressing the tRNACAGSer in presence of copper sulfate (2.5 mM) and also in presence of cadmium chloride (50 µM) (90%) relative to the control cells. Sorbitol (1.5M), pH6 and menadione (150 μM) had near neutral effects, but growth was very poor in presence of caffeine (10 mM), calcium chloride (0.75 M), chromium trioxide (0.5 mM) and EDTA (0.5 mM). Therefore, mistranslation produces antagonistic pleiotropic phenotypes that CUG reassignment expanded the adaptive ecological landscape of the CTG clade ancestor by allowing it to proliferate in ecological niches where WT cells could not survive or competed poorly with the mistranslating cells.

Figure 8. Partial CUG reassignment produces pleiotropic phenotypes in yeast. The growth rate of cells mistranslating the CUG codon as Leu/Ser relative to the control strain in presence of 18 different environmental conditions was measured. Results represent growth advantage (> 0) or disadvantage (< 0) relative to control strain (pRS315). Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. of duplicates of 3 independent clones (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 one-way Anova post Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test with CI 95% relative to pRS315).

Discussion

The discovery of codon reassignments raises a series of new questions about the evolution of the genetic code and the biological relevance of altering codon identity. Two theories have been proposed to explain the evolution of codon reassignments, namely the near-neutral “codon capture theory”28-30 and the non-neutral “ambiguous intermediate theory.”31 The former postulates that biased genome G+C pressure erases codons from the genome and that such codons can be re-introduced through mutation, acquiring a new meaning without altering protein structure.30,32 This theory is strongly supported by the disappearance of the A+T rich AUA (Ile) and AGA (Arg) and the CGG (Arg) codons in Micrococcus sp and Mycoplasma sp, whose genome G+C is 75% and 25%, respectively.33-35 However, this is a controversial theory because mitochondria have very high A+T content, use the full set of 61 sense codons of the genetic code and some of the reassigned codons violate the A+T biases, for example, the reassignment of the UAA stop codon to Trp and AAA (Lys) to Asn.2 The ambiguous intermediate theory postulates that mutant misreading tRNAs introduce codon ambiguities whose selection led to codon reassignment through disappearance of the cognate tRNAs.36 This theory implies that codon misreading produces phenotypic advantages that allow for selection of the mutant misreading tRNAs. However, the theory does not explain what kind of selective advantages may arise from codon misreading, creating the difficulty of explaining how codon misreading is sustained and fixed. We have previously demonstrated that codon ambiguity and biased G+C pressure work in similar ways since CUG ambiguity erased almost all CUGs from the genome of the CTG clade ancestor,9 suggesting that over time the toxicity of codon ambiguity can be eliminated. But, it has been remarkably difficult to explain how the ambiguous tRNACAGSer was maintained over the time frame of CUG elimination. The discovery that codon ambiguity can be advantageous under specific ecological conditions37-41 is, therefore, of paramount importance to explain the evolution of genetic code alterations. One may not find the specific ecological condition of CUG reassignment, but the selective advantages produced by codon ambiguity raise the possibility that ambiguous tRNAs can be selected. The other main issue raised by the ambiguous intermediate theory is the molecular mechanism of codon ambiguity. Clearly, tRNAs are not the only molecules that influence codon decoding fidelity and other translational factors are likely involved in codon reassignment. This has been demonstrated by the multiple reassignments of stop codons in many phylogenetic groups, which are associated with mutations in both release factors42,43 and tRNAs/aaRS pairs,44,45 and also by the expansion of the genetic code to incorporate selenoscysteine46 and pyrrolysine47 where a series of novel translational factors are involved.

The near-neutral role of the SerRS in CUG reassignment

Our data demonstrate that the evolutionary pathway of CUG reassignment in the fungal CTG clade is linked to the evolution of the tRNACAGSer. Indeed, no relevant roles have yet been found for the SerRS and LeuRS or any other translational factor in this reassignment pathway.9 Therefore, the study of the phylogeny, structure and function of the tRNACAGSer is likely to elucidate how the CTG clade ancestor reassigned the CUG codon. Our aminoacylation data show similar serylation efficiencies for the WT and mutant tRNASer, confirming that the SerRS did not play an active role in CUG reassignment.14 This can be explained by the yeast serylation determinants. The yeast SerRS does not interact with the anticodon of yeast tRNASer and serylation is dependent on the discriminator base G73 and 3 GC base pairs located in the extra-arm, away from the anticodon-arm.21,48,49 Our in vivo forced evolution data supports this hypothesis as inactivating mutations accumulated in the extra-arm and acceptor-stem of the tRNACAGSer, rather than in the anticodon-arm (Fig. 5B). We have identified mutations in tRNA structural domains that are not known to interact with the SerRS, namely the C65 to A65 mutation and deletion of C56 in the TΨC-arm, but these mutations likely disrupted the tRNA L-shape fold and targeted the tRNA for degradation (Fig. S1). Indeed, C56 forms a non-Watson-Crick tertiary interaction with G19 in the D-arm and is essential for the correct folding of the cloverleaf structure into the L-shape 3D structure, while C65 is critically located between the TΨC and acceptor stems50 and its substitution may alter the structure of the TΨC loop. The G73 to A73 inactivating mutation identified in our forced evolution experiment is very exciting because A73 is a leucylation discriminator while G73 is a serylation discriminator.20,48,51,52 Indeed, tRNASer are efficiently leucylated if the G73 discriminator (typical of Ser tRNAs) is mutated to A73.20 Moreover, the converse mutation of A73→G73 changes human tRNALeu into a Ser-isoacceptor, showing minimal structural requirements for conversion of tRNALeu into tRNASer and vice-versa. These observations raise the intriguing question of how the CTG clade LeuRS recognizes the tRNACAGSer containing G73. Previous in vitro and in vivo data from our laboratory show that the C. albicans LeuRS recognizes and charges the WT tRNACAGSer, leading to approximately 3% incorporation of Leu at CUG sites,8 despite the presence of G73 in the tRNACAGSer. It will be interesting to crystalize and determine the 3D-structure of the LeuRS-tRNACAGSer complex in order to solve this puzzling question.

Apart from the mutations mentioned above, our forced evolution screen identified U5 and A1 mutations in the acceptor stem of the tRNACAGSer. The U5 mutation destabilized and decreased sharply the serylation of the tRNACAGSer (Figs. S1 and S2), likely due to disruption of the tRNACAGSer interaction with the SerRS.21 Finally, the mutations identified in the extra-arm hit the main serylation identity determinants (three GC base pairs) and prevented serylation of the tRNACAGSer by the SerRS18,19 (Fig. S2). Selection of these mutations by forced evolution is likely associated with lack of serylation and destabilization of the mutant tRNA, as shown in Figures S1 and S2.

Roles of the tRNACAGSer in CUG reassignment

The phylogenetic data obtained to date strongly support the hypothesis that a minimal set of mutations in the anticodon-arm of the tRNACAGSer are the key elements of CUG reassignment.9 Our data showed that toxicity levels associated with Ser misincorporation were A35+G37+G33 > A35 > A35+G37, while β-gal activity and thermo stability data indicated that Ser misincorporation was similar in the three mutants. Anticodon context rules posit that 5′-CAG-3′ anticodons require a methyl group at G37 (m1G37) instead of A37 to prevent frameshifting during mRNA decoding.11 Therefore, translational fidelity pressure may have led to selection of the G37 mutation. This raises the possibility that the lower toxicity of the A35+G37 mutant is due to both increased decoding accuracy and increased leucylation efficiency, as m1G37 is a leucylation determinant.15 The G33 mutation is interesting and surprising. Available tRNA crystal structures show that the U33 is required for the turn of the anticodon-loop (U-turn). G33 distorts the turn of the phosphate backbone in the anticodon-loop and alters the structure of the RNA helix of the anticodon-stem.12,13,53 Therefore, the selective pressure that drove selection of the G33 mutation is still unclear, but it is likely that G33 keeps leucylation of the tRNACAGSer within tolerable limits, as G33 is a leucylation antideterminant.11

Our most surprising result was the strong negative impact of the anticodon-loop mutations on the expression of the mutant tRNAs. We were not able to identify the molecular mechanism that mediates that tRNA downregulation, but possible explanations are repression of Pol III transcription of the tDNACGASer gene, or increased turnover of the expressed mutant tRNACGASer. The former hypothesis is unlikely because the mutant and control tDNA genes were cloned in the same plasmid with identical upstream and downstream sequences. Since Pol III promoters are intragenic and the flanking sequences have little influence on transcription, one is tempted to assume that repression of Pol III transcription may not explain the downregulation of the mutant tRNACGASer. However, the mutations introduced in the anticodon-loop of the tRNACGASer may have altered the pattern of modification of the anticodon-arm or distorted the RNA-helix of the anticodon-stem, targeting the tRNA for degradation. The previous finding that G33 distorts the anticodon-stem helix of the tRNACAGSer13 supports this hypothesis. More interestingly, our data show that the mutant tRNACAGSer are not degraded by known tRNA degradation pathways since their expression in yeast cells harboring knockouts in the genes involved in tRNA degradation, namely RNY1, XRN1, TRF4, TRF5, MET22, AIR2 genes, did not increase tRNACGASer expression (Fig. S4). However, one cannot exclude compensatory effects due to functional redundancy of the tRNA metabolism pathways, i.e., knocking out one pathway may not produce a visible phenotype due to compensatory upregulation of the other pathways.

Putative pathway of CUG reassignment

The non-neutral evolution of the CTG clade genetic code alteration involving two chemically distinct amino acids (Ser is polar while Leu is hydrophobic) poses a significant biological problem whose solution is still incomplete. Indeed, our reconstruction model of the reassignment pathway shows that Ser misincorporation at CUG sites has major negative impact on fitness, raising the puzzling question of how the tRNACAGSer was selected under negative pressure. The results described here highlight a new feature of the evolution of this genetic code alteration, namely that low level expression of the misreading tRNAs may have minimized Ser misincorporation at CUGs, reducing initial proteome instability and the negative impact on fitness. The combination of the selective advantages produced by Ser misincorporation in specific environmental conditions and decreased toxicity associated with tRNA downregulation may have allowed Ser misincorporating cells to explore expanded ecological landscapes. In other words, we can envision an evolutionary scenario where the negative impact of Ser misincorporation was not an impediment to gradual reassignment of the CUG codon. We postulate that such scenario allowed time for accommodation of the Ser misincorporations through accumulation of compensatory mutations in the genome.

Materials and Methods

Strains and growth conditions

Saccharomyces cerevisiae BMA64 strain (EUROSCARF, acc. number 20000D, genotype MATa/MATa; ura3-52/ura3-52; trp1∆2/trp1∆2; leu2-3_112/leu2-3_112; his3-11/his3-11; ade2-1/ade2-1; can1-100/can1-100), CEN-PK2 (EUROSCARF, acc. number 30000D, genotype MATa/MATα ura3-52/ura3-52; trp1-289/trp1-289; leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112; his3Δ 1/his3Δ 1; MAL2-8C/MAL2-8C; SUC2/SUC2´), BY4743 (EUROSCARF, acc. number 20000D, genotype MATa/MATα his3Δ 0/his3Δ 0; leu2Δ /leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0/MET15; LYS2/lys2Δ 0; ura3Δ 0/ura3Δ 0) and respective BY4743 knockouts for RNY1 (EUROSCARF, acc. number Y22129), XRN1 (EUROSCARF, acc. number Y34540), TRF4 (EUROSCARF, acc. number Y36265), TRF5 (EUROSCARF, acc. number 31145), MET22 (EUROSCARF, acc. number Y31756) and AIR2 (EUROSCARF, acc. number Y33873) were grown at 30°C with or without agitation (180 rpm) in YPD + 2% agar (Formedium) or minimal medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 100 µg/ml of each of the required amino acids, 2% glucose, 2% agar) (Formedium). In the case of yeast expressing the integrative tRNA, YPD medium was supplemented with 200 mg/l of geneticin (Formedium, #G4185). Candida albicans CAI4 strain (ura3D::imm434/ura3::imm434) was grown at 30°C with or without agitation (180 rpm) in YPD medium. Escherichia coli strain DH5α (F- φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk-, mk+) phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 λ-) was grown at 37°C with or without agitation (180 rpm) in LB broth medium or in LB 2% agar (Formedium) supplemented with ampicilin 50 µg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich).

Plasmids construction and transformation

For heterologous expression of the C. albicans tRNACGASer gene in yeast, a genomic DNA fragment of 150 bp encoding the C. albicans tRNACGASer gene (AAATTTGACAGTGTGGCCGAGCGGTTAAGGCGTCTGACTCGAATCTTATTCGCGTTATCAGTTGGGCTTTGCCCGCGCAGGTTCGAATCCTGCTGCTGTCGTCATAAGTTATTTTTTTGTTTCTTGAATATTTTTTTCCCAC) retrieved from Candida Genome Database (www.candidagenome.org), previously amplified by PCR and digested with BamHI and SalI restriction enzymes (Fermentas) was ligated to single-copy expression vector pRS315 using T4 DNA ligase (Fermentas). Ligations were transformed in E. coli DH5α competent cells using standard transformation protocols. (Sambrook et al., 2008) Plasmid DNA was extracted using plasmid mini prep kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced. The mutations proposed for the evolutionary pathway, namely the A35 insertion, A37→G37 transition and U33→G33 transversion were introduced in sequential order in tRNACGASer gene previously cloned in plasmid pRS315 by site directed mutagenesis (SDM) using Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas). Briefly, in the pRS315 plasmid containing the tRNACGASer WT sequence (plasmid WT) was inserted by SDM an adenosine into the middle position of the anticodon (position 35) of the tRNACGASer gene, originating the A35 plasmid. The A37→G37 transition was inserted into tRNACGASer gene containing the A35 mutation (A35 plasmid) by SDM originating the A35+G37 plasmid. Finally, the transversion of U33→G33 was introduced in the tRNACGASer gene containing the A35 and G37 mutations (A35+G37 plasmid) by SDM originating the A35+G37+G33 plasmid. Details of the oligonucleotides used and plasmids constructed are listed in Tables S1 and S2. All SDM reactions were performed with 50 ng of plasmid template DNA in 1x Pfu DNA polymerase buffer, 2 mM MgSO4, 20 pmol of each specific oligonucleotide (Table S1), 200 µM of each dNTP and 2.5 units of Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas) in a final volume of 50 µl. PCR reactions were performed in a thermal cycler (BioRad) using a standard program of 95°C 30 sec followed by 18 cycles (95°C 30 sec, 55°C 1 min, 68°C 7 min). The SDM products were digested for 2 h at 37°C with 20 unit of DpnI (Fermentas) and then transformed in DH5α competent cells. Plasmid DNA was extracted using minipreparation kits and sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

S. cerevisiae BMA64 cells were transformed using the lithium acetate method,54 with pRS315 and the constructed plasmids (WT, A35, A35+G37 and A35+G37+G33). Transformants were selected in minimal medium lacking leucine and the tDNA genes were amplified directly from yeast colonies and were sequenced using oligonucleotides listed in Table S1.

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequence of Ser and Leu tRNAs from CTG clade species were retrieved from the Candida Gene Order Browser version 2.0 (cgob.ucd.ie/). tRNA sequences were aligned using multiple sequence alignments with CLC Sequence Viewer 6 software. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using a maximum-likelihood (ML) method with Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (Mega 5) software.55 Bootstraps were estimated from 1,000 nonparametric bootstrap runs.

Forced evolution methodology

The Candida albicans tRNACAGSer gene fused with the KanMX4 gene and the KanMX4 gene were amplified by PCR from the plasmids pUA69 and pUA707,25 using the oligonucleotides listed in Table S1. PCR products (500 ng) previously purified with QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) were integrated into the genome of S. cerevisiae CEN-PK2 using the PCR-based gene disruption method.56 Cells were selected in YPD+geneticin (200 mg/l) (Formedium). KanMX4 and tRNA gene integrations were confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. Selected clones containing the tRNACAGSer gene integrated into the genome were grown overnight in YPD+geneticin and then collected, washed and transferred to sporulation medium (1% potassium acetate, 0.1% yeast extract and 0.05% glucose) until sporulation occurred. Spores were dissected using a MSM System Series 300 micromanipulator (Singer) as described previously.25 From grown spores, DNA was extracted using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) and tRNACAGSer gene was amplified by PCR and sequenced using the oligonucleotides listed in Table S1.

In vitro tRNA synthesis

tRNA constructs for in vitro transcription containing a T7 promoter and the WT C. albicans tRNACGASer sequence were assembled using six DNA oligonucleotides (Table S1), which were first annealed and then ligated between HindIII and BamHI restriction sites of plasmid pUC19. In the resulting plasmid were inserted by SDM the single mutation A35, the double mutation A35+G37 and the triple mutation A35+G37+G33. All the oligonucleotides used and details of the plasmids constructed are listed in Tables S1 and S2. In vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase was performed as previously described.57 Transcripts were fractioned on 8% polyacrilamide-8 M urea gels and were eluted from the gels using a dialysis membrane (Dialysis tubing, high retention seamless cellulose tubing, Sigma), in 0.5x TBE, 150 V, 2 h. Prior to use, tRNAs were refolded as described previously.58

Aminoacylation assays

Aminoacylation of tRNA was performed at 30°C in 100 mM HEPES-KOH pH = 7.6, 20 µM of serine/L-[3H(G)]-Serine (500 Ci/mol) (Perkin Elmer, # NET248001MC), 15 mM magnesium chloride, 4 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 15 mM potassium chloride, 0.1 mg/ml BSA and 5 µM tRNA transcripts. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 nM of purified SerRS10,59 and aliquots (13 µl) of the reaction mixture were spotted onto Whatman 3MM discs at various time intervals. Discs were washed for 10 min in 5% TCA and once with ethanol for 10 sec, at room temperature. Radiolabelled aminoacyl-tRNA was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter).

β-Galactosidase assays

Yeast cells expressing the empty plasmid (pRS315), WT and the mutant tRNACGASer were co-transformed with the multi-copy vector pGL-C1 which contains the β-Galactosidase (β-gal) gene under the control of the GPD promoter and is fused with the glutathione S-transferase (GST-β-gal). Yeast cells expressing both vectors were selected on minimal medium lacking Leu and Trp. The resulting double transformants were named Gal-pRS315, Gal-Wt, Gal-A35, Gal-A35+G37 and Gal-A35+G37+G33. β-gal thermoinactivation was monitored directly in yeast cells as described previously.14,60 Briefly, 500 µl of exponentially growing yeast cells transformed both with pGL-C1 and each one of the plasmids expressing the mutant tRNAs were harvested, washed and ressuspended in 800 μl of Z-buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4·2H2O, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.0), 20 μl of 0.1% SDS and 50 μl of chloroform. Cell suspension was vortex for 30 sec and incubated at 47°C from T0’ up to T15’ in triplicates. This β-gal unfolding step was followed by a refolding step, performed by incubating samples on ice for 30 min. To quantify the residual β-gal activity samples were incubated at 30°C for 5 min and 200 µl of o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) (4 mg/ml) (Calbiochem, #48712) were then added to each tube. Reactions were allowed to proceed for 2 min and then stopped by addition of 400 µl of 1 M Na2CO3. Cell suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min and OD420 was measured. Relative β-Gal thermoinactivation was calculated as the % of variation of β-gal activity at each time point, relative to cells that were not incubated at 47°C.

Total β-gal activity was determined as described previously61 with small modifications. Briefly, 500 µl of yeast cells in mid-exponential phase were collected, washed, ressuspended in 250 µl of breaking buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl pH 8, 1 mM DTT and 20% Glycerol), 12.5 µl of PMSF (40 mM in 100% isopropanol) and 150 µl of glass beads. Cells were disrupted with three cycles (5,000 rpm 10 sec followed of 2 min on ice) in a Precellys system (Omni international). Cells suspensions were centrifuged at 2,300 × g for 15 min and 990 µl of Z buffer were added to 10 µl of cell extracts. Extracts were incubated at 30°C with 200 µl of ONPG (4mg/ml) until a pale yellow color appeared. Reactions were stopped with 500 µl of 1 M Na2CO3 and OD420 was measured. Protein concentration of cell extracts was quantified using the BCA protein quantification kit (Pierce). Activity of β-gal was calculated as follows: Activity = (OD420 × 1.7)/ [protein concentration (mg/ml) × volume extract (ml) × time (minutes)]. β-gal activity was normalized relative to the activity of control cells (Gal-pRS315).

tRNA isolation

RNA was isolated by hot-phenol method62 with few modifications. Briefly, 250 ml cultures grown until early stationary phase were harvested and frozen overnight at -80°C. Cell pellets were ressuspended in 12 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) and 12 ml of acid phenol chloroform (5:1 pH 4.7, Sigma), vigorous mixed (vortex) and heated at 65°C for 1 h. The aqueous phase was separated from the phenolic phase by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Aqueous phase was re-extracted with same volume of phenol by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and next with the same volume of Chloroform Isoamyl Alcohol 24:1 (Fluka). RNA was precipitated overnight at -30°C with 3 volumes of ethanol 100% and 0.1 volumes of 3M sodium acetate pH 5.2. RNAs were harvest by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, ressuspended in 0.1M sodium acetate pH 4.5 and applied to a 50 ml DEAE-cellulose (Sigma, #D3764) column equilibrated with the same buffer as previously described.14 tRNAs were washed with 0.1 M sodium acetate/0.3 M sodium chloride, eluted with 0.1 M sodium acetate/1 M sodium chloride, precipitated with ethanol and ressuspended in 10 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5/1 mM EDTA. For deacylation, 200 µg of tRNAs were incubation at 37°C, 1 h in 1M Tris pH 8.0/1M EDTA buffer, followed by ethanol precipitation and were resuspended in 20 µl of 10 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5/1 mM EDTA.

Northern blot analysis

tRNAs were fractioned in polyacrylamide gels as previously described.24 Briefly, 50 µg of total tRNAs were fractionated in 12–15% polyacrylamide (40% Acril:Bis) gels containing 8 M urea (30 cm long, 0.8 mm thick), buffered with 1x TBE pH 8.0 at room temperature, 550 V for 15 h. For acidic northern blot analysis 50 µg of total tRNAs acylated and deacylated were fractionated in 6.5% polyacrylamide (40% Acril:Bis) gels containing 8M urea buffered with 0.01 M sodium acetate (pH = 4.5) at 4°C, 250 V for 36 h. Fractionated tRNAs were transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham, #RPN203N) using a Semy-Dry Trans Blot (Bio-Rad) at 0.8 mA/cm2 of membrane for 35–45 min. Immobilization of transferred RNAs on membranes was performed employing the STRATAGENE UV crosslinker (Stratagene). Membranes were pre-hybridized at 55°C during 2 h in hybridization solution (6x SSPE/0.05% SDS/5x Denhardt’s solution; 50x Denhardt's solution = 0.02% bovine, serum albumin, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone and 0.02% Ficoll). Probes were prepared by incubating at 37°C for 1 h, reactions containing 10 pmol of dephosphorilated oligonucleotides and 4 µl of ɣ-32P-ATP (3000Ci/mmol) (Perkin Elmer, #NEG002A250UC) in 1x T4 kinase buffer with 10 mM spermidine and 16 units of T4 kinase (Takara, #2021A). Labeled probes were extracted with phenol:chlorophom:isolamyl alcohol (Sigma). Membrane hybridization was performed overnight in 10 ml of hybridization solution with ɣ-32P-ATP-labeled probe. Membranes were washed at hybridization temperature four times during 3 min in 2x SSPE/0.5% SDS, wrapped in saran wrap and exposed 24 h to a K-screen and visualized using a Molecular Imager FX (Biorad). Probes used for northern blot analysis are listed in Table S1.

Phenomics of mistranslating strains

Phenotyping analysis was performed as described previously63 with few modifications. Briefly, yeast cells were grown until middle exponential phase and 1 × 108 cells were collected. Six 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted using a liquid handling station (Caliper LifeSciences) in plates with minimal medium lacking Leu, supplemented with the appropriate stressor. After 5 d of growth, the diameter of the colonies was measured using Image J software. The growth rate of each dilution was scored relative to the non-stress control plate. These growth rate values were normalized for the control strain (pRS315) and the final percentage of growth score was obtained by calculating the median growth rate of all dilutions in each stress condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.D.M. was financially supported by FCT (PhD grant SFRH/BD/2006/27867). We thank Rita Rocha for her help with SerRS purification. This study was funded by FEDER/FCT projects PTDC/BIA-MIC/099826/2008 and PTDC/BIA-GEN/110383/2009.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- tRNA

transfer RNA

- SerRS

Seryl-tRNA synthetase

- LeuRS

Leucyl-tRNA synthetase

- Leu

leucine

- Ser

serine

- SDM

site-directed mutagenesis

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- GST-β-gal

glutathione S-transferase (GST) and β-galactosidase genes

- ONPG

o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside

- ɣ-32P-ATP

ATP labelled with phosphor 32

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Crick FH. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968;38:367–79. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knight RD, Freeland SJ, Landweber LF. Rewiring the keyboard: evolvability of the genetic code. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:49–58. doi: 10.1038/35047500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szymański M, Barciszewski J. The genetic code--40 years on. Acta Biochim Pol. 2007;54:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler G, Rasmussen MD, Lin MF, Santos MA, Sakthikumar S, Munro CA, et al. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature. 2009;459:657–62. doi: 10.1038/nature08064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohama T, Suzuki T, Mori M, Osawa S, Ueda T, Watanabe K, et al. Non-universal decoding of the leucine codon CUG in several Candida species. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4039–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.17.4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos MAS, Tuite MF. The CUG codon is decoded in vivo as serine and not leucine in Candida albicans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1481–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos MA, Ueda T, Watanabe K, Tuite MF. The non-standard genetic code of Candida spp.: an evolving genetic code or a novel mechanism for adaptation? Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:423–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5891961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomes AC, Miranda I, Silva RM, Moura GR, Thomas B, Akoulitchev A, et al. A genetic code alteration generates a proteome of high diversity in the human pathogen Candida albicans. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R206. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massey SE, Moura G, Beltrão P, Almeida R, Garey JR, Tuite MF, et al. Comparative evolutionary genomics unveils the molecular mechanism of reassignment of the CTG codon in Candida spp. Genome Res. 2003;13:544–57. doi: 10.1101/gr.811003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha R, Pereira PJ, Santos MA, Macedo-Ribeiro S. Unveiling the structural basis for translational ambiguity tolerance in a human fungal pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14091–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102835108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki T, Ueda T, Watanabe K. The ‘polysemous’ codon--a codon with multiple amino acid assignment caused by dual specificity of tRNA identity. EMBO J. 1997;16:1122–34. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quigley GJ, Rich A. Structural domains of transfer RNA molecules. Science. 1976;194:796–806. doi: 10.1126/science.790568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perreau VM, Keith G, Holmes WM, Przykorska A, Santos MA, Tuite MF. The Candida albicans CUG-decoding ser-tRNA has an atypical anticodon stem-loop structure. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:1039–53. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos MAS, Perreau VM, Tuite MF. Transfer RNA structural change is a key element in the reassignment of the CUG codon in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 1996;15:5060–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda I, Silva RM, Santos MAS. Evolution of the genetic code in yeasts. Yeast. 2006;23:203–13. doi: 10.1002/yea.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curran JF, Yarus M. Reading frame selection and transfer RNA anticodon loop stacking. Science. 1987;238:1545–50. doi: 10.1126/science.3685992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asahara H, Himeno H, Tamura K, Nameki N, Hasegawa T, Shimizu M. Escherichia coli seryl-tRNA synthetase recognizes tRNA(Ser) by its characteristic tertiary structure. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:738–48. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achsel T, Gross HJ. Identity determinants of human tRNA(Ser): sequence elements necessary for serylation and maturation of a tRNA with a long extra arm. EMBO J. 1993;12:3333–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu XQ, Gross HJ. The long extra arms of human tRNA((Ser)Sec) and tRNA(Ser) function as major identify elements for serylation in an orientation-dependent, but not sequence-specific manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5589–94. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitschopf K, Gross HJ. The discriminator bases G73 in human tRNA(Ser) and A73 in tRNA(Leu) have significantly different roles in the recognition of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:405–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himeno H, Yoshida S, Soma A, Nishikawa K. Only one nucleotide insertion to the long variable arm confers an efficient serine acceptor activity upon Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA(Leu) in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:704–11. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenhard B, Orellana O, Ibba M, Weygand-Durasević I. tRNA recognition and evolution of determinants in seryl-tRNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:721–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geiduschek EP, Tocchini-Valentini GP. Transcription by RNA polymerase III. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:873–914. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varshney U, Lee CP, RajBhandary UL. Direct analysis of aminoacylation levels of tRNAs in vivo. Application to studying recognition of Escherichia coli initiator tRNA mutants by glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24712–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva RM, Paredes JA, Moura GR, Manadas B, Lima-Costa T, Rocha R, et al. Critical roles for a genetic code alteration in the evolution of the genus Candida. EMBO J. 2007;26:4555–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soma A, Kumagai R, Nishikawa K, Himeno H. The anticodon loop is a major identity determinant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA(Leu) J Mol Biol. 1996;263:707–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos MAS, Cheesman C, Costa V, Moradas-Ferreira P, Tuite MF. Selective advantages created by codon ambiguity allowed for the evolution of an alternative genetic code in Candida spp. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:937–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osawa S, Jukes TH, Watanabe K, Muto A. Recent evidence for evolution of the genetic code. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:229–64. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.229-264.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osawa S, Jukes TH. Codon reassignment (codon capture) in evolution. J Mol Evol. 1989;28:271–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osawa S, Jukes TH. On codon reassignment. J Mol Evol. 1995;41:247–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00170679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz DW, Yarus M. Transfer RNA mutation and the malleability of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:1377–80. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seaborg DM. Was Wright right? The canonical genetic code is an empirical example of an adaptive peak in nature; deviant genetic codes evolved using adaptive bridges. J Mol Evol. 2010;71:87–99. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9373-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oba T, Andachi Y, Muto A, Osawa S. CGG: an unassigned or nonsense codon in Mycoplasma capricolum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:921–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kano A, Andachi Y, Ohama T, Osawa S. Novel anticodon composition of transfer RNAs in Micrococcus luteus, a bacterium with a high genomic G + C content. Correlation with codon usage. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:387–401. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohama T, Muto A, Osawa S. Role of GC-biased mutation pressure on synonymous codon choice in Micrococcus luteus, a bacterium with a high genomic GC-content. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1565–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schultz DW, Yarus M. On malleability in the genetic code. J Mol Evol. 1996;42:597–601. doi: 10.1007/BF02352290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bacher JM, Waas WF, Metzgar D, de Crécy-Lagard V, Schimmel P. Genetic code ambiguity confers a selective advantage on Acinetobacter baylyi. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6494–6. doi: 10.1128/JB.00622-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pezo V, Metzgar D, Hendrickson TL, Waas WF, Hazebrouck S, Döring V, et al. Artificially ambiguous genetic code confers growth yield advantage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8593–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402893101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bender A, Hajieva P, Moosmann B. Adaptive antioxidant methionine accumulation in respiratory chain complexes explains the use of a deviant genetic code in mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16496–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802779105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahapatra A, Patel A, Soares JA, Larue RC, Zhang JK, Metcalf WW, et al. Characterization of a Methanosarcina acetivorans mutant unable to translate UAG as pyrrolysine. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:56–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos MA, Ueda T, Watanabe K, Tuite MF. The non-standard genetic code of Candida spp.: an evolving genetic code or a novel mechanism for adaptation? Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:423–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5891961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukai T, Hayashi A, Iraha F, Sato A, Ohtake K, Yokoyama S, et al. Codon reassignment in the Escherichia coli genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8188–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heinemann IU, Rovner AJ, Aerni HR, Rogulina S, Cheng L, Olds W, et al. Enhanced phosphoserine insertion during Escherichia coli protein synthesis via partial UAG codon reassignment and release factor 1 deletion. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3716–22. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen PR, Groff D, Guo J, Ou W, Cellitti S, Geierstanger BH, et al. A facile system for encoding unnatural amino acids in mammalian cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:4052–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang F, Robbins S, Guo J, Shen W, Schultz PG. Genetic incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Böck A, Forchhammer K, Heider J, Leinfelder W, Sawers G, Veprek B, et al. Selenocysteine: the 21st amino acid. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:515–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan G, James CM, Krzycki JA. Pyrrolysine encoded by UAG in Archaea: charging of a UAG-decoding specialized tRNA. Science. 2002;296:1459–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1069588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breitschopf K, Gross HJ. The exchange of the discriminator base A73 for G is alone sufficient to convert human tRNA(Leu) into a serine-acceptor in vitro. EMBO J. 1994;13:3166–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Normanly J, Ollick T, Abelson J. Eight base changes are sufficient to convert a leucine-inserting tRNA into a serine-inserting tRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5680–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du X, Wang E-D. Tertiary structure base pairs between D- and TpsiC-loops of Escherichia coli tRNA(Leu) play important roles in both aminoacylation and editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2865–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breitschopf K, Achsel T, Busch K, Gross HJ. Identity elements of human tRNA(Leu): structural requirements for converting human tRNA(Ser) into a leucine acceptor in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3633–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metzger AU, Heckl M, Willbold D, Breitschopf K, RajBhandary UL, Rösch P, et al. Structural studies on tRNA acceptor stem microhelices: exchange of the discriminator base A73 for G in human tRNALeu switches the acceptor specificity from leucine to serine possibly by decreasing the stability of the terminal G1-C72 base pair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4551–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashraf SS, Ansari G, Guenther R, Sochacka E, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. The uridine in “U-turn”: contributions to tRNA-ribosomal binding. RNA. 1999;5:503–11. doi: 10.1017/S1355838299981931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gietz RD, Woods RA. High efficiency transformation with lithium acetate, In: Johnston ER, ed. Molecular genetics of yeast: a pratical approach. Oxford, England: IRL Press at Oxford University Press, 1994: 121-34. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorenz MC, Muir RS, Lim E, McElver J, Weber SC, Heitman J. Gene disruption with PCR products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1995;158:113–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00144-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sampson JR, Uhlenbeck OC. Biochemical and physical characterization of an unmodified yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA transcribed in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1033–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geslain R, Aeby E, Guitart T, Jones TE, Castro de Moura M, Charrière F, et al. Trypanosoma seryl-tRNA synthetase is a metazoan-like enzyme with high affinity for tRNASec. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38217–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rocha R, Barbosa Pereira PJ, Santos MA, Macedo-Ribeiro S. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the seryl-tRNA synthetase from Candida albicans. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2011;67:153–6. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110048542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. In: Sialiano I, ed. Methods in yeast genetics, a cold spring harbor laboratory course manual. 2000 Edition. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. In: Argentin J, ed. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Third Edition. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Köhrer K, Domdey H. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:398–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94030-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kvitek DJ, Will JL, Gasch AP. Variations in stress sensitivity and genomic expression in diverse S. cerevisiae isolates. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.