Abstract

Background

Acute transfusion reactions are probably common in sub-Saharan Africa, but transfusion reaction surveillance systems have not been widely established. In 2008, the Blood Transfusion Service of Namibia implemented a national acute transfusion reaction surveillance system, but substantial under-reporting was suspected. We estimated the actual prevalence and rate of acute transfusion reactions occurring in Windhoek, Namibia.

Methods

The percentage of transfusion events resulting in a reported acute transfusion reaction was calculated. Actual percentage and rates of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 transfused units were estimated by reviewing patients’ records from six hospitals, which transfuse >99% of all blood in Windhoek. Patients’ records for 1,162 transfusion events occurring between 1st January – 31st December 2011 were randomly selected. Clinical and demographic information were abstracted and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Healthcare Safety Network criteria were applied to categorize acute transfusion reactions1.

Results

From January 1 – December 31, 2011, there were 3,697 transfusion events (involving 10,338 blood units) in the selected hospitals. Eight (0.2%) acute transfusion reactions were reported to the surveillance system. Of the 1,162 transfusion events selected, medical records for 785 transfusion events were analysed, and 28 acute transfusion reactions were detected, of which only one had also been reported to the surveillance system. An estimated 3.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.3–4.4) of transfusion events in Windhoek resulted in an acute transfusion reaction, with an estimated rate of 11.5 (95% CI: 7.6–14.5) acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 transfused units.

Conclusion

The estimated actual rate of acute transfusion reactions is higher than the rate reported to the national haemovigilance system. Improved surveillance and interventions to reduce transfusion-related morbidity and mortality are required in Namibia.

Keywords: blood safety, blood transfusion, blood transfusion/adverse effects, surveillance, Namibia

Introduction

Since the 1980s, programmes and policies related to blood transfusion safety in sub-Saharan Africa have focused on reducing the risk of transmitting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections via transfusions2–4. While much has been done to quantify the risk of HIV transmission through blood transfusion5–9 and to identify risk-reduction strategies10–14, there is limited information related to other adverse transfusion outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa, including acute transfusion reactions such as sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor unit and haemolysis secondary to transfusion with ABO-incompatible blood products. However, based on data from industrialised countries15–18, previously published reports describing unsafe transfusion practices5,19–21, and some limited studies from the region which have evaluated adverse transfusion-related outcomes22,23, acute transfusion reactions in sub-Saharan Africa are probably more common than clinically recognised.

Surveillance systems designed to monitor and detect serious transfusion reactions are now in place in most industrialised countries as part of national haemovigilance systems, although the methodology and extent of implementation differ15,16,24. With the exception of South Africa, such systems have historically been absent in sub-Saharan Africa25. In Namibia, a country with a population of 2.1 million people in south-western Africa, the Blood Transfusion Service of Namibia (NAMBTS) is the only organisation authorised to collect, process, and distribute blood and blood components intended for transfusion. From 2000–2007, suspected transfusion reactions in the country were reported to NAMBTS using a non-standardised process which did not include clinical investigation or a comprehensive laboratory follow-up for reported events. As a result, reporting clinicians received limited feedback from the blood service and the system was under-utilised. In 2008, NAMBTS implemented a national haemovigilance system which included a systematic method of reporting, along with comprehensive clinical and laboratory investigations of all reported acute transfusion reactions in the country. This system is intended to provide timely, comprehensive feedback to support the implementation of corrective measures to reduce transfusion-associated morbidity and mortality. In 2010, NAMBTS conducted a national audit of transfusion practices in all 46 transfusion facilities and found a lack of standardised transfusion practice between facilities and health care practitioners (personal communication: B. Lohrke, 25 July 2012). Using the results of the audit, NAMBTS revised its training curriculum and launched the “BeST: Better and Safer Transfusions” training programme based on an Australian model26. The NAMBTS “BeST” program is designed to strengthen training related to clinical transfusion practices, patient monitoring, and reporting of acute transfusion reactions. Under the revised reporting process, all healthcare workers who order or perform transfusions are asked to voluntarily report all acute transfusion reactions to NAMBTS. As a first step, the blood bank technologist and the on-call NAMBTS medical officer are notified via telephone by the reporting facility. The medical officer provides clinical guidance and specific instructions related to sample collection. This telephone call is followed by submission of a standard, paper-based transfusion reaction report, along with the patient’s samples and the remaining unused contents of the blood unit to NAMBTS via courier.

Between 2000–2007, reports of acute transfusion reactions increased from three to ten per year (personal communication B. Lohrke 25 July, 2012). Following the launch of the national haemovigilance system in 2008, the number of reports continued to increase, but despite comprehensive training and outreach activities, only 20 reactions (0.1%) were reported out of approximately 20,000 units transfused nationally in 2010. Few published studies have estimated the prevalence or rate of acute transfusion reactions in sub-Saharan Africa22,27,28, but this number probably reflects under-recognition and reporting as acute transfusion reactions have been reported to occur in approximately 1–3% of all transfusions in other countries29. In order to enhance monitoring of blood transfusions, facilitate the implementation of corrective measures to protect transfusion recipients, and reduce the future occurrence of adverse events, quantifying the burden of acute transfusion reactions and determining the associated morbidity and mortality are important objectives for blood services in the region. This study was conducted to estimate the prevalence and rate of acute transfusion reactions occurring in Windhoek, Namibia, and, by using retrospective review of medical records, to compare the estimated prevalence of adverse events with the prevalence reported to the NAMBTS haemovigilance system. The probable diagnoses and severity of acute transfusion reactions occurring in Windhoek are also described.

Materials and methods

Approvals and informed consent

All data were collected following approval from the Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services (MOHSS). Because the study involved the evaluation of a routine surveillance programme, it was considered exempt from review by an Institutional Review Board by the office of the Associate Director for Science of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Global HIV/AIDS in Atlanta, GA, USA.

Study sites and design

Due to logistical and resource constraints, the study was limited to six transfusion facilities in Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. These facilities collectively transfuse >99% of all blood in Windhoek. In 2010, 8,580 (36%) of the 23,744 blood units transfused in Namibia were transfused in the six selected facilities. Except in rare cases in which whole blood may be clinically indicated (e.g., neonatal exchange transfusion), all transfusions in Namibia are conducted using blood components. Since most patients are transfused more than one unit of blood in a 24-hour period, for the present study, “transfusion events,” rather than individual units, were reviewed in the medical records for evidence of an acute transfusion reaction. A transfusion event was defined as a single episode encompassing the duration of transfusion and the 24-hour period following cessation of transfusion in which a patient received any combination of components and/or number of units for one clinical indication.

Calculation of the prevalence of acute transfusion reactions as reported to the surveillance system

To determine the percentage of transfusion events resulting in acute transfusion reactions that were reported to the surveillance system, case reports submitted to NAMBTS by the six selected Windhoek facilities between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011 were reviewed. These documents contained clinical, laboratory, and radiographic data, and results of the NAMBTS investigation. The likely diagnosis determined by the NAMBTS investigators was recorded for each report. The denominator for the calculation of the percentage of reported transfusion events resulting in acute transfusion reactions was the total number of transfusion events occurring in the six selected Windhoek hospitals in 2011.

Estimation of the percentage and rate of acute transfusion reactions

Given the suspected under-reporting of adverse transfusion events, we estimated an actual percentage and rate of acute transfusion reactions occurring in the Windhoek facilities. This estimated percentage was based on a review of patients’ records and compared with the percentage reported to the surveillance system. The sample size of medical records needed for review for the Windhoek study sites was determined based on a published estimated acute transfusion reaction rate of 1%29. A sample size of 1,162 was selected for this study as this would produce a two-sided 95% exact confidence interval (95% CI) with a total width of 1% when the detected percentage is 1%30. The observed sample size of 785 would have yielded a 95% CI with a total width of 1.5% for an estimated acute transfusion reaction rate of 1%. A roster of patients’ medical records representing 1,162 randomly selected transfusion events was generated through a SQL query of the electronic NAMBTS database. Transfusion events were eligible if they occurred between January 1 and December 31, 2011, and if specific identifier information (e.g., patient’s name, date of transfusion) was available to facilitate location of the medical record in the facilities. The selected transfusion events were intended to be representative of Windhoek for the specified time-frame.

Data collection

Patients’ records were retrospectively evaluated during February-April 2012 for evidence of an acute transfusion reaction occurring during or within 24 hours of the final unit in the transfusion event. Data abstracted from the medical records were collected using the Census and Survey Processing System (CSPro) (U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, USA). The patient’s demographic information, documentation from physicians and/or nurses, laboratory data, and radiographic findings were reviewed for each medical record. Pertinent demographic and clinical information related to each transfusion event were entered into the CSPro tool which was programmed to assign a likely acute transfusion reaction diagnosis, severity score, and imputability score for each transfusion event. Imputability is defined as the likelihood that the reaction was associated with the transfusion event1. These scores were based on criteria described in the CDC National Healthcare Safety Network Haemovigilance Module (NHSN)1. If the physician’s or nurse’s documentation, laboratory, or radiographic findings did not suggest an acute transfusion reaction, the CSPro programme assigned a diagnosis of “none”. For transfusion events assigned to the “none” category, severity and imputability scores were not calculated.

If the documentation in the medical record suggested an acute transfusion reaction had occurred, a diagnosis, based on NHSN criteria1, was generated by the preprogrammed CSPro algorithm. Diagnoses included: allergic, acute haemolytic, febrile non-haemolytic, hypotensive, sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor unit, transfusion-associated circulatory overload, transfusion-associated dyspnoea, and transfusion-related acute lung injury1. If documentation indicated that an acute transfusion reaction had occurred, but the data available were insufficient for the algorithm to assign a specific diagnosis, a designation of “transfusion reaction, not otherwise specified” was assigned. Based on available documentation for each transfusion event for which an acute transfusion reaction had occurred, severity scores were calculated as mild, moderate, life-threatening, or fatal. Imputability scores were designated as: possible, probable, or definite. Only two investigators (S.V. Basavaraju and B. Lohrke) could override the CSPro algorithms and assign new diagnoses, severity, or imputability scores. All acute transfusion reactions detected through the review of patients’ medical records were further evaluated to determine whether they had been reported by hospital staff to the surveillance system. All acute transfusion reactions detected through the record review, which were either designated as life-threatening or fatal, were subsequently referred for investigation by NAMBTS. The results of subsequent investigations are not presented here.

Statistical analysis

The percentages of transfusion events resulting in an acute transfusion reaction as reported to the surveillance system, and as determined by medical chart abstraction, were calculated and compared using a one proportion Z-test. The percentages of transfusion events resulting in a reported or an unreported acute transfusion reaction were estimated using the total sampled transfusion events as the denominator. The reported rate of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 units was calculated using the total units transfused during 2011 at the selected facilities as the denominator. The estimated rate of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 units was calculated using data collected from the medical records.

Estimated rates of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 units of each component type were also calculated using data collected from the medical records. For these estimates, a fraction of each acute transfusion reaction detected in the study sample was attributed to each component in proportion to the number of component units transfused during the respective transfusion event (e.g., 0.75 acute transfusion reactions were attributed to packed red blood cells (PRBC) if three PRBC units and one platelet unit were transfused during the transfusion event). The relative standard error was calculated for rates of acute transfusion reactions for each type of component. The estimated percentage and rates were weighted to account for variation in non-response between facilities. The weight adjustments were defined as [1/total response rate] at each facility. Application of sample weights allowed for adjustment of prevalence and rate estimates to reduce bias resulting from non-response. Confidence intervals were adjusted using a finite population correction factor31. All data were analysed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Weighted analyses were performed using SAS survey procedures.

Results

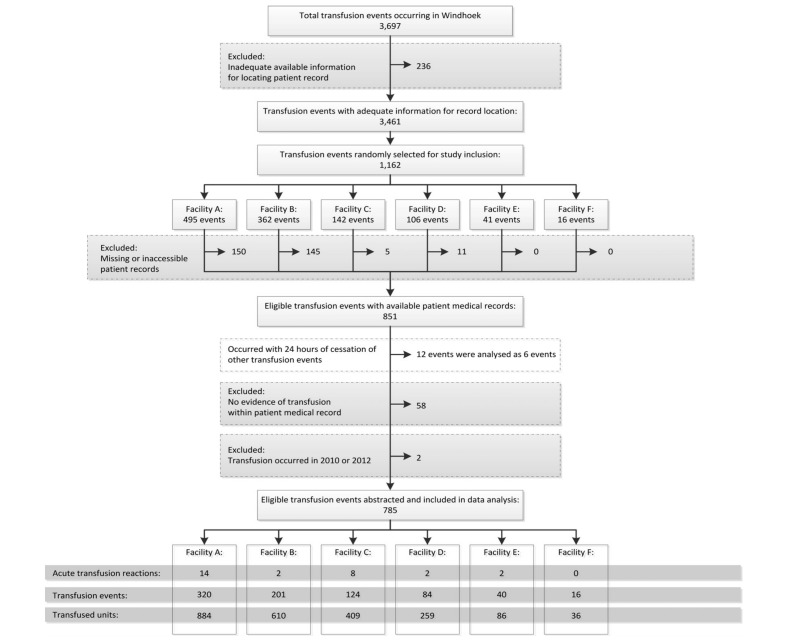

Between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011, 3,697 transfusion events, which included 10,373 units of blood components (7,777 adult and paediatric PRBC, 1,894 adult and paediatric fresh frozen plasma [FFP], 686 adult and paediatric platelets, and 16 whole blood units) occurred in the six Windhoek hospitals. NAMBTS received reports of eight acute transfusion reactions from these facilities during this period. Of these 3,697 transfusion events, there was sufficient information in the NAMBTS database to facilitate location of the patients’ medical records for 3,461 (94%) events (Figure 1). From these 3,461 transfusion events, 1,162 events were selected via simple random sampling. Patients’ medical records for 311 events were either missing or otherwise inaccessible in the facilities and were excluded. After reviewing the patients’ medical records for the remaining 851 transfusion events, 12 transfusion events occurred within 24 hours of a second randomly sampled event for the same patient and were collectively analysed as six transfusion events. After reviewing the patients’ medical records for the remaining 845 transfusion events, another 58 events were excluded because the medical record contained evidence that the transfusion was cancelled or there was no documentation that the transfusion had occurred. Two transfusion events selected for review occurred during 2010 or 2012 and were excluded, leaving 785 transfusion events for data analysis (Figure 1). This total included 2,284 blood units (1,688 adult and paediatric PRBC, 446 adult and paediatric FFP, 148 adult and paediatric platelets, and two whole blood units).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of transfusion events reviewed for evidence of an acute transfusion reaction (Windhoek, Namibia, January 1 – December 31, 2011).

Of the eight acute transfusion reactions reported to the surveillance system in 2011 four were mild, two were moderate severity; and one resulted in death (Table I). The severity score for the remaining reported acute transfusion reaction was not documented in the surveillance report. Of the 785 transfusion events documented in patients’ medical records which were retrospectively reviewed, 28 medical records contained evidence that an acute transfusion reaction had occurred during or after the associated transfusion event. Of the 28 acute transfusion reactions detected through the chart review, only one, an allergic reaction, had also been reported to the surveillance system. Twenty of the 28 acute transfusion reactions were classified as mild, four were moderate severity, two were life-threatening and two resulted in death (Table II). Documentation was not sufficient to assign a specific diagnosis for seven acute transfusion reactions, resulting in a classification of “transfusion reaction not otherwise specified”. Based on physician and nursing documentation of clinical signs and symptoms, one of the life-threatening acute transfusion reactions identified through the medical record review was classified by the CSPro algorithm as sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor unit. One of the two deaths identified through the medical record review was designated by the CSPro algorithm as an acute haemolytic reaction. For both of these transfusion events, the clinical signs and symptoms were documented while monitoring the patient during and immediately following the transfusion event. However, our findings suggest that the clinical staff did not recognise that the signs and symptoms could have resulted from an acute transfusion reaction and neither of these suspected reactions was reported to the surveillance system. For these events, laboratory data, required by NHSN criteria to assign an imputability score of “definite” were not available. However, the clinical details were strongly suggestive of these diagnoses resulting in the imputability designations of possible (sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor unit) and probable (acute haemolytic reaction).

Table I.

Diagnoses and severity scores of acute transfusion reactions reported to the national acute transfusion reaction surveillance system: Windhoek, Namibia - 2011.

| Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Diagnosis | Mild | Moderate | Life-threatening | Fatal | Not documented | Total |

| Acute haemolytic | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Allergic | 1 | 1* | - | - | - | 2 |

| Febrile non-haemolytic | 3 | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| Hypotensive | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| donor unit | ||||||

| Transfusion-associated circulatory overload | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Transfusion-associated dyspnoea | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Transfusion reaction not otherwise specified | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Total | 4 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | 8 |

Reaction was also detected by reviewing a selected sample of transfusion events.

No cases of transfusion-related acute lung injury were reported to the surveillance system.

Table II.

Diagnoses and severity scores of acute transfusion reactions as determined by reviewing a selected sample of transfusion events: Windhoek, Namibia - 2011.

| Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Diagnosis | Imputability | Mild | Moderate | Life-threatening | Fatal | Total |

| Acute haemolytic | 1 | |||||

| Definite | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Probable* | - | - | - | 1 | - | |

| Possible | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Allergic | 3 | |||||

| Definite | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | |

| Probable | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Possible | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Febrile non-haemolytic | 10 | |||||

| Definite | 4 | - | - | - | - | |

| Probable | 5 | - | - | - | - | |

| Possible | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Hypotensive | 1 | |||||

| Definite | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Probable | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Possible | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor unit | 1 | |||||

| Definite | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Probable | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Possible* | - | - | 1 | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Transfusion-associated dyspnoea | 5 | |||||

| Definite | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Probable | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Possible | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Transfusion reaction not otherwise specified | 7 | |||||

| Definite | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Probable | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Possible | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 20 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 28 | |

Laboratory data were unavailable. Clinical scenario, signs, and symptoms were highly consistent with these diagnoses, resulting in the imputability designations. No cases of transfusion-related acute lung injury were detected reviewing a selected sample of transfusion events.

The Total column designates the total number of reactions detected in each diagnostic category.

Imputability scores were based on criteria described in the CDC National Healthcare Safety Network Haemovigilance Module and were designated as: Possible, Probable, or Definite. In this table, for each diagnosis, only imputability categories for detected acute transfusion reactions are listed in the Imputability column. For example, no acute haemolytic reactions with “Possible” or “Definite” imputablity designations were detected in this study. Hence, “Possible” and “Definite” are not included in the Imputability column for acute haemolytic reactions.

Based on reports received by the surveillance system (eight acute transfusion reactions in 3,697 transfusion events), the percentage of total transfusion events in Windhoek resulting in an acute transfusion reaction was observed to be 0.2% (Table III). The estimated percentage of reported and non-reported acute transfusion reactions calculated from the medical record review was 3.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.3–4.4). This estimate was significantly higher than the percentage determined by reports to the surveillance system (P<0.01).

Table III.

Reported and estimated percentage of acute transfusion reactions, rate of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 transfused units, and estimated rate of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 transfused blood component units: Windhoek, Namibia - 2011.

| Number of acute transfusion reactions | Total number of transfusion events | Percentage (%) | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported percentage | 8 | 3,697 | 0.2 | - | - |

| Estimated percentage | 28 | 785 | 3.4 | [2.3–4.4] | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Number of acute transfusion reactions | Total number of transfused units | Rate | 95% CI | ||

|

| |||||

| Reported rate per 1,000 transfused units | 8 | 10,338 units | 0.8 | - | |

| Estimated rate per 1,000 transfused units | 28 | 2,284 units | 11.5 | [8.0–15.0] | |

|

| |||||

| Component type | Total number of components transfused | Estimated rate per 1,000 transfused units | 95% CI | RSE* (%) | |

|

| |||||

| Packed red blood cells | 1,688 | 12.9 | [8.7–17.2] | 17 | |

| Fresh-frozen plasma | 446 | 4.9 | [1.4–8.4] | 36 | |

| Platelets | 148 | 15.0 | [1.0–29.0] | 48 | |

RSE: Relative standard error. While there is no set cut-off, estimates with a RSE greater than 30% may be statistically unreliable and should be interpreted with caution46.

The rate of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 blood units transfused was 0.8 when calculated using the eight transfusion reactions reported to the surveillance system (10,338 blood units transfused). This number increased to 11.5 (95% CI: 8.0–15.0) acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 blood units transfused when calculated using the number of reactions identified through the medical chart review. The adjusted estimated rates of acute transfusion reactions by component type transfused were: 12.9 (95% CI: 8.7–17.2) per 1,000 adult and paediatric PRBC units; 4.9 (95% CI: 1.4–8.4) per 1,000 adult and paediatric FFP units, and; 15.0 (95% CI: 1.0–29.0) per 1,000 adult and pediatric platelet units. No acute transfusion reactions were detected for the two whole blood units transfused in the study sample.

Discussion

The findings of this study reinforce previously published observations that morbidity and mortality related to acute transfusion reactions are a substantial public health problem in sub-Saharan Africa22. This study found that a significantly greater percentage of transfusion events occurring in Windhoek resulted in an acute transfusion reaction than were reported to the surveillance system in 2011. Four severe transfusion reactions, including two deaths, were not reported to the surveillance system. While laboratory data were not available to designate “definite” imputability based on NHSN criteria, two of these severe reactions were highly consistent with sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor unit and acute haemolytic reactions. The occurrence of these unreported severe transfusion reactions is concerning, but suggests that implementation of targeted interventions to improve bedside monitoring of patients’ signs and symptoms around the time of transfusion and facilitate reporting of suspected reactions to the surveillance system, could effectively reduce transfusion-related morbidity and mortality in Namibia. Consistent with previous observations, we found a higher rate of acute transfusion reactions to platelet transfusions, followed by PRBC and FFP transfusions15.

Some studies, restricted to one or few hospitals, have described prevalence and rates of acute transfusion reactions elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, with some reporting regional, not facility-based, estimates22,27,28,32. Due to differences in methodology, these reports describe widely varying rates and percentages of transfusions resulting in acute transfusion reactions 22,27,28,32. The transfusion reaction rate reported here is generally comparable with another rate reported elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa28. The rates and percentages described here are higher than those reported in industrialised countries16,17,33–36. While this may reflect safer transfusion practices in industrialised countries, some of the differences may be attributable to varying representativeness35, reporting practices36,37, classification schemes16,17, and disease definitions adopted by individual transfusion reaction surveillance systems33. Furthermore, this study design may have resulted in higher percentages and rates than those described in other countries. Reviewing medical records for clinical evidence of acute transfusion reactions as described in this study constitutes “active” surveillance and may result in higher estimated rates and percentages of acute transfusion reactions than the “passive” surveillance method used by the NAMBTS haemovigilance system, which relies on healthcare worker reporting38.

The discrepancy between the reported and estimated percentages of acute transfusion reactions occurring in Windhoek may have two possible explanations: (i) a lack of transfusion reaction-related knowledge among healthcare workers, and (ii) infrastructure-related challenges. Since the launch of the national transfusion reaction surveillance system in Namibia, extensive training and outreach activities have been conducted by NAMBTS. However, given frequent staff turnover and movement of healthcare workers within and between facilities, many individuals involved in ordering or performing transfusions may not have yet participated in these training activities, resulting in reduced awareness related to appropriate monitoring of patients, and transfusion reaction recognition and reporting. As NAMBTS continues outreach and training activities and enhances awareness among healthcare workers, acute transfusion reaction reporting should improve. In neighbouring South Africa, a steady increase in reporting has been observed as the blood service has increased education and awareness activities among healthcare workers39. Addressing infrastructure-related barriers to reporting will likely pose a continued challenge in Namibia and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Limited telecommunication capacity40, challenges related to specimen transport41 and few available transfusion medicine specialists42 may preclude adequate reporting and investigation of acute transfusion reactions in these resource-limited settings. In Namibia, a national electronic medical record system is planned and once implemented, could be linked with NAMBTS to ease reporting challenges. While electronic systems may improve transfusion reaction reporting36, similar systems may be difficult to implement in other more resource-limited settings of sub-Saharan Africa.

Targeted interventions to address non-infectious causes of adverse transfusion reactions may provide an additional safety benefit to transfusion recipients in Namibia and similar settings. Nearly one-third of the acute transfusion reactions identified through the chart review were febrile non-haemolytic reactions with five respiratory-related transfusion reactions and three allergic reactions. Leucoreduction with filtration has been previously demonstrated to reduce the incidence of febrile, non-haemolytic reactions in industrialised countries43. However, this procedure is not routinely performed by NAMBTS because of cost considerations (personal communication R. Wilkinson,7 April 2012)*. Furthermore, it has been suggested that anaphylactic or other allergic acute transfusion reactions could be prevented by transfusing IgA-deficient plasma44. This intervention is unlikely to be feasible because of testing capacity or cost considerations in sub-Saharan Africa. Some interventions may, however, be implemented at low or limited cost. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload may be prevented by diuretic therapy and slowing the transfusion rate for patients previously experiencing this reaction44. The occurrence of respiratory complications, including transfusion-related acute lung injury, may be prevented by preparing FFP solely from male or nulliparous female donors44. Given the relatively low use of FFP in Namibia, this intervention is unlikely to raise costs associated with component preparation or targeted donor recruitment.

A substantial burden of bacterial contamination of donor blood units has been reported in sub-Saharan Africa23. Consistent with this observation, our study detected at least one likely instance of sepsis due to bacterial contamination of the donor blood unit. These findings suggest that implementation of targeted interventions to decrease bacterial contamination of donated blood units in sub-Saharan Africa may reduce transfusion-related morbidity and mortality. Many interventions, previously demonstrated to be effective in industrialised countries, could be implemented in the region at low or minimal cost. Some of these, including deferral of donors with signs of illness or who have recently undergone medical or dental procedures and limitation of storage time prior to initiating transfusions, have already been instituted in Namibia35. Furthermore, NAMBTS has implemented diversion pouches to reduce bacterial entry into donor units45. An additional effective low-cost intervention which could be broadly implemented is a timed, double-swab disinfection protocol of the skin prior to collection, which is currently planned in Namibia in response to the findings of this study45. Consistent with observations in industrialised countries, our study also found high rates of transfusion reactions to platelets15. Given existing challenges with storage and transportation, other blood services in the region may consider the need for additional infrastructure improvements prior to implementation of platelet production.

This study is subject to the following limitations. Only transfusion events occurring in Windhoek were included in the study sample. It may not be possible to generalise the findings to all of Namibia or to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Documentation in the medical records may have been incomplete and laboratory and radiographic data were frequently unavailable. This may have resulted in underestimation or misclassification of acute transfusion reactions detected. Several medical records were not located in two facilities. As a result, information on the patients’ demographics, blood component types and number of units, and clinical signs and symptoms related to transfusion events contained within these records are unknown. Despite some statistical adjustments, non-response bias cannot be excluded. Probably because of the relatively small numbers of FFP and platelet units included in the study sample, the relative standard error for estimates of acute transfusion reactions per 1,000 units transfused for each of these component types exceeded 30%. While there is no set cut-off, estimates with a relative standard error greater than 30% may be statistically unreliable and should be interpreted with caution46.

While blood services have made substantial progress toward improving the safety and adequacy of blood supplies in many sub-Saharan African countries47, several challenges related to improving transfusion safety remain, especially those addressing adverse outcomes with non-infectious and infectious aetiologies. These findings highlight an important gap in current investments in blood safety in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the area of patients’ safety during and following transfusions. Future studies in the region should reassess the burden of acute transfusion reactions after implementing targeted interventions. National health authorities and external donors should consider expanding current blood safety projects to emphasise transfusion safety and surveillance for adverse transfusion reactions, as well as the prevention of transfusion-transmissible infections.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Fernando Carlosama for CSPro programming assistance and Justina Anghuwo, Salmi Imbondi, and Deon Van Zyl for assistance with medical record abstraction.

Footnotes

NAMBTS currently performs buffy coat depletion on PRBC units prior to storage.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The use of trade names is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Authorship contributions

The roles of all co-authors in this study are described below. Benjamin P.L. Meza participated in the study design, data collection, and data analysis; Sridhar V. Basavaraju and Britta Lohrke participated in the study design, study supervision, data collection, and data interpretation; John P. Pitman, Robert Wilkinson, Naomi Bock, and David W. Lowrance, participated in the study design, study supervision, and data interpretation; Ray W. Shiraishi, participated in the study design and data analysis; Matthew J. Kuehnert and Mary Mataranyika participated in the study design and data interpretation. All authors participated in writing the manuscript and approved its final content. RWS had full access to all of the data and takes responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Manual: Biovigilance Component. Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed on 25/07/2013]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/Biovigilance/BV-Protocol-1-3-1-June-2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO. AIDE-MEMOIRE for National Blood Programmes. [Accessed on 03/02/2011]. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/bloodsafety/Blood_Safety_Eng.pdf.

- 3.McFarland W, Mvere D, Shandera W, Reingold A. Epidemiology and prevention of transfusion-associated human immunodeficiency virus transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Vox Sang. 1997;72:85–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.1997.7220085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming AF. HIV and blood transfusion in sub-Saharan Africa. Transfus Sci. 1997;18:167–79. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3886(97)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore A, Herrera G, Nyamongo J, et al. Estimated risk of HIV transmission by blood transfusion in Kenya. Lancet. 2001;358:657–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05783-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baggaley RF, Boily MC, White RG, Alary M. Risk of HIV-1 transmission for parenteral exposure and blood transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2006;20:805–127. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218543.46963.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consten EC, van der Meer JT, de Wolf F, et al. Risk of iatrogenic human immunodeficiency virus infection through transfusion of blood tested by inappropriately stored or expired rapid antibody assays in a Zambian hospital. Transfusion. 1997;37:930–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37997454020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colebunders R, Ryder R, Francis H, et al. Seroconversion rate, mortality, and clinical manifestations associated with the receipt of a human immunodeficiency virus-infected blood transfusion in Kinshasa, Zaire. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:450–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefrere JJ, Dahourouh H, Dokekias AE, et al. Estimate of the residual risk of transfusion-transmitted human immunodeficiency virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a multinational collaborative study. Transfusion. 2011;51:486–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allain JP. Moving on from voluntary non-remunerated donors: who is the best blood donor? Br J Haematol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basavaraju SV, Mwangi J, Nyamongo J, et al. Reduced risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV in Kenya through centrally co-ordinated blood centres, stringent donor selection and effective p24 antigen-HIV antibody screening. Vox Sang. 2010;99:212–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang CT, Field SP, Busch MP, Heyns AdP. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 and hepatitis C virus RNA among South African blood donors: estimation of residual transfusion risk and yield of nucleic acid testing. Vox Sang. 2003;85:9–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagny CT, Mbanya D, Leballais L, et al. Reduction of the risk of transfusion-transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by using an HIV antigen/antibody combination assay in blood donation screening in Cameroon. Transfusion. 2011;51:184–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulst Mv, Sagoe KW, Vermande JE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV screening of blood donations in Accra (Ghana) Value Health. 2008;11:809–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreu G, Morel P, Forestier F, et al. Hemovigilance network in France: organization and analysis of immediate transfusion incident reports from 1994 to 1998. Transfusion. 2002;42:1356–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stainsby D, Jones H, Asher D, et al. Serious hazards of transfusion: a decade of hemovigilance in the UK. Transfus Med Rev. 2006;20:273–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller-Stanislawski B, Lohmann A, Gunay S, et al. The German Haemovigilance System--reports of serious adverse transfusion reactions between 1997 and 2007. Transfusion Med. 2009;19:340–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth VR, Kuehnert MJ, Haley NR, et al. Evaluation of a reporting system for bacterial contamination of blood components in the United States. Transfusion. 2001;41:1486–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41121486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackritz EM, Campbell CC, Ruebush TK, et al. Effect of blood transfusion on survival among children in a Kenyan hospital. Lancet. 1992;340:524–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91719-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lackritz EM, Ruebush TK, Zucker JR, et al. Blood transfusion practices and blood-banking services in a Kenyan hospital. AIDS. 1993;7:995–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zucker JR, Lackritz EM, Ruebush TK, et al. Anaemia, blood transfusion practices, HIV and mortality among women of reproductive age in western Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:173–6. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbanya D, Binam F, Kaptue L. Transfusion outcome in a resource-limited setting of Cameroon: a five-year evaluation. Int J Infect Dis. 2001;5:70–3. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(01)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassall O, Maitland K, Pole L, et al. Bacterial contamination of pediatric whole blood transfusions in a Kenyan hospital. Transfusion. 2009;49:2594–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Health Service Biovigilance Task Group. Biovigilance in the United States: efforts to bridge a critical gap in patient safety and donor health. [Accessed on 03/07/2012]. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/bloodsafety/biovigilance/ash_to_acbsa_oct_2009.pdf.

- 25.Nel T, Heyns AP. Hemovigilance Annual Report: Blood Transfusion Services of South Africa. Bloemfontein, South Africa: South African National Blood Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevenson L. Blood Matters - better safer transfusion program. [Accessed on 26/06/2012]. Available at: http://docs.health.vic.gov.au/docs/doc/A96B65A26E02A508CA2578E30021163E/$FILE/Victoria's%20Better%20Safer%20Transfusion%20(BeST)%20Program%20-%20Report%20July%202006.pdf.

- 27.Arewa OP, Akinola NO, Salawu L. Blood transfusion reactions; evaluation of 462 transfusions at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2009;38:143–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahourou H, Tapko JB, Nebie Y, et al. [Implementation of hemovigilance in Sub-Saharan Africa]. Transfus Clin Biol. 2012;19:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roush KS. Febrile, allergic, and other non-infectious transfusion reactions. In: Hillyer CD, editor. Blood banking and transfusion medicine: Basic principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. pp. 401–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natukunda B, Schonewille H, Smit Sibinga CT. Assessment of the clinical transfusion practice at a regional referral hospital in Uganda. Transfus Med. 2010;20:134–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2010.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rebibo D, Hauser L, Slimani A, et al. The French Haemovigilance System: organization and results for 2003. Transfus Apher Sci. 2004;31:145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giampaolo A, Piccinini V, Catalano L, et al. The first data from the haemovigilance system in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2007;5:66–74. doi: 10.2450/2007.0001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robillard P, Nawej KI, Jochem K. The Quebec hemovigilance system: description and results from the first two years. Transfus Apher Sci. 2004;31:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh SP, Chang CW, Chen JC, et al. A well-designed online transfusion reaction reporting system improves the estimation of transfusion reaction incidence and quality of care in transfusion practice. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:842–7. doi: 10.1309/AJCPOQNBKCDXFWU3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekker LG, Wood R. Blood safety--at what cost? JAMA. 2006;295:557–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, et al. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-13):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayob Y. Hemovigilance in developing countries. Biologicals. 2010;38:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fraser HSF, McGrath SJD. Information technology and telemedicine in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ. 2000;321:465–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens WS, Marshall TM. Challenges in implementing HIV load testing in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 1):S78–84. doi: 10.1086/650383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tagny CT, Kapamba G, Diarra A, et al. [The training in transfusion medicine remains deficient in the centres of Francophone sub-Saharan Africa: results of a preliminary study]. Transfus Clin Biol. 2011;18:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King KE, Shirey RS, Thoman SK, et al. Universal leukoreduction decreases the incidence of febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions to RBCs. Transfusion. 2004;44:25–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0041-1132.2004.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hendrickson JE, Hillyer CD. Noninfectious serious hazards of transfusion. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:759–69. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181930a6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Korte D, Curvers J, de Kort WL, et al. Effects of skin disinfection method, deviation bag, and bacterial screening on clinical safety of platelet transfusions in the Netherlands. Transfusion. 2006;46:476–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein RJ, Proctor SE, Boudreault MA, Turczyn KM. Healthy People 2010 statistical notes. Vol. 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression; pp. 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CDC. Progress toward strengthening national blood transfusion services - 14 countries, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]