Abstract

Background

The (C)ces haplotype, mainly found in black individuals, contains two altered genes: a hybrid RHD-CE-Ds gene segregated with a ces allele of RHCE with two single nucleotide polymorphisms, c. 733C>G (p.Leu245Val) in exon 5 and c. 1006G>T (Gly336Cys) in exon 7. This haplotype could be responsible for false positive genotyping results in RhD-negative individuals and at a homozygous level lead to the loss of a high incidence antigen RH34. The aim of this study was to screen for the (C)ces haplotype in Tunisian blood donors, given its clinico-biological importance.

Material and methods

Blood samples were randomly collected from blood donors in the blood transfusion centre of Sousse (Tunisia). A total of 356 RhD-positive and 44 RhD-negative samples were tested for the (C)ces haplotype using two allele-specific primer polymerase chain reactions that detect c. 733C>G (p.Leu245Val) and c. 1006G>T (p. Gly336Cys) substitutions in exon 5 and 7 of the RHCE gene. In addition, the presence of the D-CE hybrid exon 3 was evaluated using a sequence-specific primer polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Among the 400 individuals only five exhibited the (C)ces haplotype in heterozygosity, for a frequency of 0.625%. On the basis of the allele-specific primer polymerase chain reaction results, the difference in (C)ces haplotype frequency was not statistically significant between RhD-positive and RhD-negative blood donors.

Discussion

These data showed the presence of the (C)ces haplotype at a low frequency (0.625%) compared to that among Africans in whom it is common. Nevertheless, the presence of RHD-CE-Ds in Tunisians, even at a lower frequency, should be considered in the development of a molecular genotyping strategy for Rh genes, to ensure better management of the prevention of alloimmunisation.

Keywords: RHD gene, RHCE gene, (C)ces haplotype, ASP-PCR, Tunisian population

Introduction

The Rhesus (Rh) blood group system is of clinical interest because it is involved in haemolytic diseases of the newborn and haemolytic transfusion reactions. The Rh system is complex, consisting of 50 currently known antigens1. The most important antigens are D, C/c, and E/e. Rh antigens are carried on two proteins encoded by genes denoted RHD and RHCE in close proximity on chromosome 1. These genes are 97% identical, each has 10 exons and they encode proteins that differ by 32 to 35 amino acids.

The frequency of RhD-negative phenotype differs widely among races, being approximately 15% in Caucasians2 and 3% to 7% in Africans3. The frequency in Tunisian cohorts is approximately 9% to 10%4. Studies have demonstrated that the molecular mechanisms in RhD-negative individuals with different ethnic backgrounds are likewise quite diverse5. The RhD-negative phenotype in Tunisians is mainly caused by RHD gene deletion6, whereas in other ethnic groups, especially in dark-skinned (sub-Saharan) individuals who account for a relatively small proportion of the Tunisian population7, D negativity is frequently caused by aberrant RHD genes, either RHDψ or d(C)ces. The molecular characteristics of this haplotype were described by Faas and colleagues8. The (C)ces haplotype contains two altered genes: an RHD-CE-Ds hybrid gene which results from a gene conversion, favoured by the opposite orientation of the RHD and RHCE genes, and a ces allele of the RHCE gene with two single nucleotide polymorphisms: c. 733C>G (p.Leu245Val) in RHCE exon 5 and c. 1006G>T (p. Gly336Cys) in RHCE exon 7 that results in a VS+V− phenotype. Thus, the (C)ces haplotype encodes weak C, c, weak e called es and VS antigens, whereas its does not produce D and V antigens.

The most usual and common VS/V phenotype reported so far is the VS−V− phenotype; however, two other phenotypes, related to ethnic origin, have been described recently9: the VS+V+ phenotype associated with the ces allele and the VS+V− phenotype associated with the (C)ces haplotype. Moreover, an unusual phenotype, VS−Vw+, has been reported to be associated with the ceAR allele resulting from an RHCE-D-CE gene involving RHD exon 5 with c. 48G>C, c. 712 A>G, c. 733 C>G, c. 787 A>G, c. 800 T>A, c. 916A>G nucleotide substitutions: this RHCE allele has been mainly described in people of African origin10.

Pham et al.11 found, in individuals of African origin, that the (C)ces haplotype could have two different molecular backgrounds at the level of the hybrid RHD-CE-Ds: the (C)ces haplotype described by Faas and colleagues8, named “(C)ces haplotype type 1” and “(C)ces haplotype type 2”. “(C)ces haplotype type 1” is present when the hybrid RHD-CE-Ds gene consists of exons 1 and 2, parts of 3, 8, 9, and 10 from RHD and the remainder of exon 3 and exons 4 through 7 from RHCE, whereas “(C)ces haplotype type 2” is present when the hybrid RHD-CE-Ds gene consists of exons 1 and 2, complete exon 3, exons 8, 9, and 10 from RHD; and exons 4 through 7 from RHCE.

Either hybrid RHD-CE-Ds allele from (C)ces haplotype type 1 or type 2 segregates with a ces allele with two nucleotide substitutions: c. 733C>G in RHCE exon 5 and c. 1006G>T in RHCE exon 711. When present in the homozygous state, either the type 1 or type 2 (C) ces haplotype induces the absence of the high-prevalence RH34 antigen9,11 which has a high clinical incidence in the settings of obstetrics and incompatible transfusions. Such a haplotype could be also responsible for false positive results during Rh genotyping in RhD-negative cohorts.

In this study we screened for the (C)ces haplotype in Tunisian blood donors, which should be considered in a reliable genotyping strategy for RhD-negative people. We analysed genomic DNA by allele-specific primer (ASP) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for c. 733C>G and c. 1006G>T changes in RHCE exons 5 and 7, respectively, and studied the occurrence of RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 by sequence-specific (SSP)-PCR.

Materials and methods

Samples

Blood samples were collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) from 400 random blood donors at the blood transfusion centre of Sousse, Tunisia.

Serological typing

For all samples, RH antigens (D: RH1, C: RH2, E: RH3, c: RH4 and e: RH5) were serologically determined using monoclonal anti-D antibody (Biomaghreb, Ariana, Tunisia). The reagent was prepared from a blend of both IgG and IgM anti-D. The IgM anti-D agglutinates with D-positive red cells except for DVI and some weak D phenotype, whereas the IgG anti-D agglutinates with the DVI and some weak D in an indirect antiglobulin test (IAT). Bio-Rad reagents (Loos, France) were used to test for the presence of anti-C, anti-c, anti-E and anti-e antibodies using the following specificities: anti-C (RH2, clone MS24), anti-E (RH3, clone MS260), anti-c (RH4, clone MS33), and anti-e (RH5, clones MS16, MS21, MS63). Standard serological tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the IAT was performed systematically for apparently RhD-negative results.

Molecular analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood cells with the salting out method as described by Miller12. The genomic DNA of the samples studied was analysed using two ASP-PCR procedures to detect the (C)ces haplotype. The wild-type ASP-PCR was always performed in parallel to assess the homozygous status of the mutations. A PCR internal control was included in order to avoid false negative results. One sample known to be RH:-34 ((C)ces/(C)ces) had been used to validate the methods. Amplifications were carried out with Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Life technologies, São Paulo, Brazil). Primer sets are reported in Table I.

Table I.

Oligonucleotides primers used for the three polymerase chain reactions.

| Primer name | Primer direction | Sequence 5′to 3′ | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHCE-INT4F | Forward | GCAACAGAGCAAGAGTCCA | 13 |

| RH-EX5CR | Reverse | TGTCACCACACTGACTGCTAG | |

| RH-EX5GR | Reverse | TGTCACCACACTGACTGCTAC | |

| RH-EX7F | Forward | AACCCGAGTGCTGGGGATTC | |

| RHCE-EX7R | Reverse | ACCCACATGCCATTGCCGTTC | |

| RH-EX7GF | Forward | ACTCCATCTTCAGCTTGCTGG | |

| RH-EX7TF | Forward | ACTCCATCTTCAGCTTGCTGT | |

| RHD-EX3F | Forward | TCGGTGCTGATCTCAGTGGA | |

| RHCE-EX3R | Reverse | ACTGATGACCATCCTCAGGG | |

|

| |||

| HGH F | Forward | GCCTTCCCAACCATTCCCTTA | 14 |

| HGH R | Reverse | TCACGGATTTCTGTTGTGTTTC | |

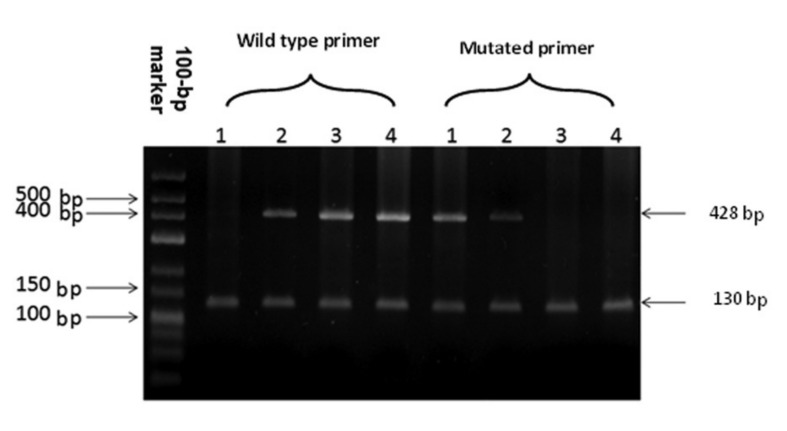

RHCE-INT4F/RH-EX5CR, RH-EX5GR primer sets were used to detect the RHCE C733G polymorphism in two separate PCR which were performed with 100 ng of genomic DNA in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. These reactions provide a 428-bp when the appropriate RHCE exon 5 sequence is present. As a control, we used a couple of primers (RH-EX7F and RHCE-EX7R) that target a non-polymorphic sequence in exon 7 of the RHCE gene, to amplify a 130 bp product. Reaction mixtures contained 0.1 μM of each primer, 200 μM of each dNTP, and 0.4 U of Taq DNA polymerase in the appropriate buffer. Amplifications were programmed on a thermal cycler (9700 GeneAmp PCR System; Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation for 5 minutes at 94 °C followed by 30 cycles carried out using the following sequence: denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 64 °C for 30 seconds and polymerisation at 72 °C for 30 seconds.

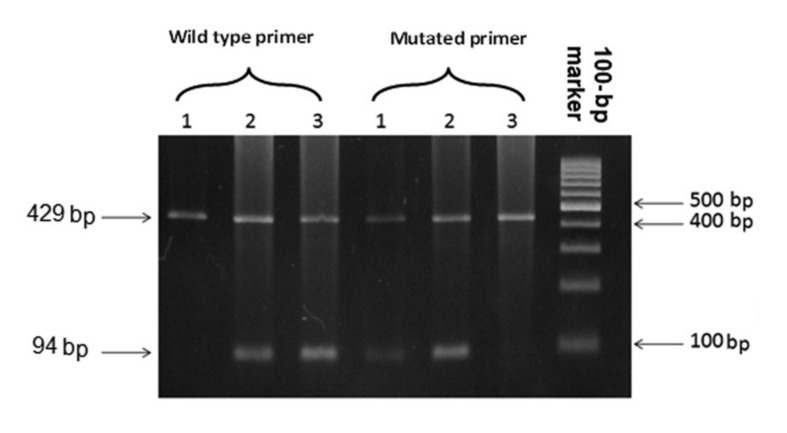

RH-EX7GF and RH-EX7TF/RHCE-EX7R primer sets were used to detect the G1006T polymorphism: these primers amplified a 94-bp product when the appropriate RHCE exon 7 sequence was present. The control primers (HGH F and HGH R) amplified a 429-bp segment of a conserved region of human growth hormone. PCR amplifications were performed using the following conditions: an initial denaturation for 5 minutes at 95 °C and then 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 seconds, 63 °C for 30 seconds and 72 °C for 30 seconds.

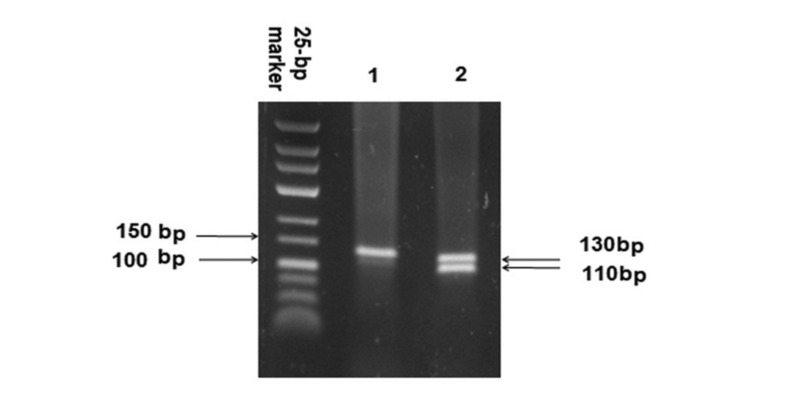

The presence of the RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 was analysed using SSP-PCR involving a forward primer (RHD-EX3F) that is specific for the 5′ end of RHD exon 3 and a reverse primer (RHCE-EX3R) that is specific for the 3′ end of RHCE exon 3. These primers will only amplify a RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 to produce a 110-bp product. The control primers (RH-EX7F and RHCE-EX7R) amplified a 130-bp product from exon 7 of RHCE. PCR amplification parameters were an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 seconds, at 65 °C for 30 seconds and at 72 °C for 45 seconds.

All PCR were terminated after extension for 10 minutes at 72 °C. The PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and visualised with ethidium bromide staining.

Statistical analysis

(C)ces haplotype screening among RhD-positive and RhD-negative donors was assessed using the Student’s t statistical test.

Results

Serological analysis

Serological tests were performed for the 400 blood donors of whom 356 were typed RhD-positive and 44 typed RhD-negative. DCcee was found to be the most prevalent phenotype (44.38%) among RhD-positive blood donors and ddccee (68.18%) the most prevalent among RhD-negative blood donors.

Molecular biology

ASP-PCR DNA analysis of RHCE exons 5 and 7 and SSP-PCR of RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 were carried out in all donors to detect the c. 733C>G and c. 1006G>T polymorphisms and the RHD-CE-D gene; these combined nucleotides and hybrid exon 3 have been associated with the presence of (C)ces haplotype type 1.

Five samples of which one was RhD-negative with the ddCcee phenotype and four were RhD-positive including two samples with a DCcee phenotype and two others with a DCcEe phenotype exhibited, in a heterozygous state, both c. 733C>G (Figure 1) and c. 1006 G>T (Figure 2) substitutions in correlation with RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 (Figure 3) suggesting the presence of (C)ces haplotype type 1 with an allelic frequency of 0.625% in our studied cohort. The difference between (C)ces haplotype frequency among RhD-positive and RhD-negative blood donors was not statistically significant (Student’s t-test value=0.45). Furthermore no (C) ces type 2 allele was found and homozygosity for the (C) ces haplotype was not observed either.

Figure 1.

ASP-PCR pattern of RHCE Exon 5 1: G733/G733 (RH: -34 phenotype) 2: C733/G733 (mutation present at heterozygous level) 3, 4: C733/C733 (mutation absent).

Figure 2.

ASP-PCR pattern of RHCE Exon 7 1: T1006/T1006 (RH: -34 phenotype) 2: G1006/T1006 (mutation present at heterozygous level) 3: G1006/G1006 (mutation absent).

Figure 3.

Agarose gel showing results of SSP-PCR screening test for the RHD-CE hybrid Exon3 1: RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 absent 2: RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 present.

Among the other 395 donors testsed, ASP-PCR amplifications showed that 58 samples were from donors heterozygous for C/G at nucleotide 733 and 12 were from homozygous donors; no c. 1006G>T mutation was detected in any of these donors. The 325 remaining donors were negative for the two analysed nucleotide substitutions (Table II).

Table II.

c. 733 C>G, c. 1006 G>T and RHD-CE exon 3 PCR results.

| C733G | G1006T | RHD-CE hybrid exon 3* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhD-positive (n=356) | CC (284) | GG (284) | −(285) |

| CG (59) | GG (55) | −(55) | |

| GT (4) | + (4)** | ||

| GG (12) | GG (12) | −(12) | |

| RhD-negative (n=44) | CC (40) | GG (40) | −(40) |

| CG (4) | GG (3) | −(3) | |

| GT (1) | + (1)** |

− = RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 absent; + = RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 present;

results suggesting the presence of the (C)ces haplotype in a heterozygous state.

Discussion

In this study, genomic DNA from 400 random donors (356 RhD-positive, 44 RhD-negative) was screened for the (C)ces haplotype, which produces a low incidence antigen (VS antigen) and in a homozygous state leads to the loss of a high incidence RH34 antigen which is of clinical interest in transfusion reactions and obstetrics essentially in inter-population unions10. We used PCR amplifications to detect c. 733C>G and c. 1006 G>T nucleotide substitutions in RHCE exons 5 and 7, respectively, and to test for the presence of RHD-CE hybrid exon 3.

Our study showed the presence of c. 733C>G and c. 1006 G>T substitutions in a heterozygous state in five out of the 400 cases, as well as the RHD-CE hybrid exon 3 in favour of presence of the (C)ces haplotype in heterozygosity. This haplotype occurred in 0.625% of the Tunisians, which is much lower than the frequency reported in Africans in Mali15. The presence of this haplotype in Tunisians could be linked to the ethnic heterogeneity of Tunisian population, which is a mixture consisting mainly of Berbers -the autochthonous population- and Arabs, with a relatively small sub-Saharan African contribution that could be at the origin of the individuals carrying the (C)ces haplotype7.

Four out of the five cases were RhD-positive with DCcee and DCcEe phenotypes and, respectively, eventual DCe/d(C)ces and DcE/d(C)ces genotypes. The fifth individual was RhD-negative with a ddCcee phenotype and d(C)ces/dce genotype; the dce haplotype could have resulted from an RHD gene deletion or another RhD-negative allele such as RHDψ or an RHD-CE-D hybrid gene. These five cases exhibited the classical (C)ces haplotype as described by Faas and co-workers and named (C)ces type 1 by Pham and colleagues8,11.

The five donors carrying the (C)ces haplotype could be presumed to present the VS+V− phenotype since VS expression resulted from a c. 733C>G substitution that predicts the p. Leu245Val in the RHCE protein. Conversely, absence of V in the (C)ces haplotype was suggested to be linked to the presence of the c. 1006 G>T substitution predicting Cys336 in the protein13. In fact, two studies have shown an association between VS and RHCE G733 encoding Val245. Steers et al. identified the presence of the G733 mutation in 55 VS+ samples analysed whereas 180 VS− samples showed a C73316. Faas et al. demonstrated that 43 VS+ donors were homozygous or heterozygous for G7338. Nevertheless, the c. 733C>G and c. 1006 G>T ASP-PCR tests may not be sufficient to deduce VS and V antigenicity and only serological typing could allow a definite conclusion to be drawn about the expression of these antigens.

Fifty-eight donors were heterozygous for c. 733 C>G and 12 others were homozygous without c. 1006 G>T substitution; all of these donors appear to have the ces allele. The probable genotypes of these donors are summarised in Table III.

Table III.

Serological phenotype and probable genotype of 70 blood donors.

| Number | Phenotype | Nucleotide 733 | Nucleotide 1006 | Probable genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | DCcee (31) | C/G | G/G | DCe/ces |

| Dccee (15) | C/G | G/G | Dce/ces | |

| DccEe (9) | C/G | G/G | DcE/ces | |

| ddccee (3) | C/G | G/G | dce/ces | |

| 12 | Dccee (12) | G/G | G/G | Dces/ces |

It was well established in previous studies that the (C) ces haplotype when present in a homozygous state results in the RH:-34 phenotype11 which is of marked clinical relevance in transfusion settings and obstetrics10,17. Given the presence of this haplotype in the cohort we studied, in a heterozygous state with a frequency of 0.625%, it can be presumed that the RH:-34 phenotype exists in the Tunisian population.

Thus, in Tunisia the RHD-CE-Ds allele should be considered in the development of a molecular strategy for RHD genotyping of RhD-negative people by targeting at least three RHD-specific sequences, in order to limit false positive results, particularly in foetal RhD genotyping.

Footnotes

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Daniels G. The molecular genetics of blood group polymorphism. Hum Genet. 2009;126:729–42. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0738-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westhoff CM. The structure and function of the Rh antigen complex. Semin Hematol. 2007;44:42–50. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Touinssi M, Chapel-Fernandes S, Granier T, et al. Molecular analysis of inactive and active RHD alleles in native Congolese cohorts. Transfusion. 2009;49:1353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hmida S, Karrat F, Mojaat N, et al. Rhesus system polymorphism in the Tunisian population. Rev Fr Transfus Hemobiol. 1993;36:191–6. doi: 10.1016/s1140-4639(05)80233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner FF, Flegel WA. RHD gene deletion occurred in the Rhesus box. Blood. 2000;95:3662–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moussa H, Tsochandaridis M, Chakroun T, et al. Molecular background of D-negative phenotype in the Tunisian population. Transfus Med. 2012;22:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Moncer W, Bahri R, Esteban E, et al. Research of the origin of a particular Tunisian group using a physical marker and Alu insertion polymorphisms. Genet Mol Biol. 2011;34:371–6. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572011005000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faas BHW, Beckers EAM, Wildoer P, et al. Molecular background of VS and weak C expression in blacks. Transfusion. 1997;37:38–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37197176949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham BN, Peyrard T, Juszczak G, et al. Analysis of RhCE variants among 806 individuals in France: considerations for transfusion safety, with emphasis on patients with sickle cell disease. Transfusion. 2011;51:1249–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noizat-Pirenne F, Lee K, Le Pennec P-Y, et al. Rare RHCE phenotypes in black individuals of Afro-Caribbean origin : identification and transfusion safety. Blood. 2002;100:4223–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pham BN, Peyrard T, Juszczak G, et al. Heterogenous molecular background of the weak C, VS+, hrB_, HrB_ phenotype in black persons. Transfusion. 2009;49:495–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller SA, Dyskes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleotide cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniels GL, Faas BHW, Green CA, et al. The VS and V blood group polymorphism in Africans: a serologic and molecular analysis. Transfusion. 1998;38:951–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.381098440860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji Y, Sun JL, Du KM, et al. Identification of a novel HLA-A*0278 allele in a Chinese family. Tissue Antigens. 2005;65:564–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner FF, Moulds JM, Tounkara A, et al. RHD allele distribution in Africans of Mali. BMC Genet. 2003;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steers F, Wallace M, Johnson P, et al. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis: a novel method for determining Rh phenotype from genomic DNA. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:417–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid ME, Storry JR, Issitt PD, et al. Rh haplotypes that make e but not hrB usually make VS. Vox Sang. 1997;72:41–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.1997.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]