Abstract

Purpose

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are battery-powered nicotine delivery systems that may serve as a “gateway” to tobacco use by adolescents. Use of e-cigarettes by U.S. adolescents rose from 3% in 2011 to 7% in 2012. We sought to describe healthcare providers’ awareness of e-cigarettes and to assess their comfort with and attitudes toward discussing e-cigarettes with adolescent patients and their parents.

Methods

A statewide sample (n = 561) of Minnesota healthcare providers (46% family medicine physicians, 20% pediatricians, and 34% nurse practitioners) who treat adolescents completed an online survey in April 2013.

Results

Nearly all providers (92%) were aware of e-cigarettes, and 11% reported having treated an adolescent patient who had used them. The most frequently cited sources of information about e-cigarettes were patients, news stories, and advertisements, rather than professional sources. Providers expressed considerable concern that e-cigarettes could be a gateway to tobacco use but had moderately low levels of knowledge about and comfort discussing e-cigarettes with adolescent patients and their parents. Compared with pediatricians and nurse practitioners, family medicine physicians reported knowing more about e-cigarettes and being more comfortable discussing them with patients (both p < .05). Nearly all respondents (92%) wanted to learn more about e-cigarettes.

Conclusions

Healthcare providers who treat adolescents may need to incorporate screening and counseling about e-cigarettes into routine preventive services, particularly if the prevalence of use continues to increase in this population. Education about e-cigarettes could help providers deliver comprehensive preventive services to adolescents at risk of tobacco use.

Keywords: Electronic cigarette, Electronic nicotine delivery system, Adolescent health, Nicotine, Smoking, Medical education

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are devices that typically look like regular cigarettes but deliver vaporized nicotine without tobacco combustion. Public interest in e-cigarettes is skyrocketing [1], but these novel products are controversial among health professionals [2]. Safety information is sparse and inconsistent [3,4], and regulation is in flux [5]. Public health experts are currently divided about whether e-cigarettes are best understood as a potential harm reduction tool for current smokers or a “gateway” to nicotine dependence and, in turn, other tobacco use.

One point of consensus, however, is that protections must be put in place to ensure that young people who are at risk for smoking initiation do not use e-cigarettes [6]. Although rates of e-cigarette use were extremely low (<1%) in one 2011 study with a national sample of U.S. adolescent males (ages 11–19) [7], more recent data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicate greater prevalence [8]. From 2011 to 2012, ever-use of e-cigarettes increased from 1% to 3% among middle school students (Grades 6–8) and from 5% to 10% among high school students (Grades 9–12). Of particular concern, nearly 10% of students who had tried e-cigarettes had never smoked a traditional cigarette. If e-cigarettes act as a “gateway” product, these youth could be at high risk for initiating tobacco use.

Several national organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, point to the important role that healthcare providers play in prevention by giving guidance to adolescent patients and their parents about risk behaviors, including tobacco use [9,10]. Current guidelines include screening for tobacco use as a part of routine health care; asking about tobacco use among patients’ families and friends; educating about health risks; and providing cessation counseling for those patients who use cigarettes or other tobacco products [9–12]. Recent evidence suggests that brief, preventive counseling with a primary care provider shows promise for decreasing adolescent risk behaviors, including smoking [13]. Although e-cigarettes, as a relatively new product, are not explicitly mentioned in current guidelines, knowledge about these nicotine-containing devices is important for providers who wish to deliver comprehensive tobacco-related counseling to their patients.

Despite the potential for healthcare providers to deliver education and guidance about e-cigarettes to adolescent patients, research has yet to explore providers’ perceptions of this emerging health issue. We sought to describe providers’ awareness of e-cigarettes and to assess their comfort with and attitudes toward discussing e-cigarettes with adolescent patients and their parents. We also aimed to explore differences in awareness and attitudes by provider age and specialty.

Methods

We surveyed a statewide sample of physicians and nurse practitioners who provide preventive care to preteens and adolescents ages 11–17 years. We identified potential participants through publicly available lists provided by the Minnesota Boards of Medical Practice and of Nursing. From these lists, we sampled providers in pediatric and family medicine specialties, excluding providers without e-mail addresses or Minnesota mailing addresses. Because our sampling frame included many providers who may not provide preventive care to adolescents (e.g., neonatal specialists), the survey used a screener question to determine eligibility. Providers who indicated on the screener that they provided preventive care to adolescent patients ages 11–17 years were eligible to participate.

In April 2013, we invited 3,923 healthcare providers to participate in the study. A total of 615 providers were eligible, gave informed consent, and completed the cross-sectional, online survey (adjusted response rate 28% based on American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) formula 4) [14]. Among those who responded to the screening questions and were eligible, the cooperation rate was 85%. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at the University of Minnesota [15]. Participants received an invitation describing the study’s purpose and providing a link to the survey. Nonresponders received up to three reminder e-mails. The present analysis uses data from 561 providers who answered questions about e-cigarettes. Providers who responded to the survey items about e-cigarettes did not differ from those who did not with regard to any of the assessed sociodemographic characteristics (all p > .05). The institutional review board at the University of Minnesota approved the study.

Measures

We developed e-cigarette items based on our previous research with adolescents [7]. We cognitively tested measures with five healthcare providers to identify potential sources of response error and improve survey items [16].

Prior to questionnaire items about e-cigarettes, the survey provided a picture of an e-cigarette accompanied by the statement: “An electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) looks like a regular cigarette, but it runs on a battery and produces nicotine vapor instead of smoke. There are many types of e-cigarettes. Some common brands are Smoking Everywhere, NJOY, Blu, and Vapor King.” The survey then assessed providers’ awareness of e-cigarettes with the question “Before today, had you ever heard of e-cigarettes?” For those who responded “yes,” questions assessed their perceived knowledge of e-cigarettes, whether they had heard about e-cigarettes from any of a list of nine potential sources (including from a patient, a colleague, an advertisement, and a professional source such as a journal article or newsletter), as well as whether they thought they had ever provided care to an adolescent patient who had used an e-cigarette.

Among all providers, the survey assessed comfort talking with adolescent patients about e-cigarettes (1 = “very uncomfortable” to 4 = “very comfortable”). Finally, seven items measured a range of attitudes and beliefs using a 4-point response scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”). These items focused on risk beliefs (“E-cigarettes are safer to use than regular cigarettes”; “E-cigarettes are safer to use than smokeless tobacco (chew, snuff, dip, etc.)”; and “E-cigarettes could be a ‘gateway’ to other tobacco use”) and communication (“My adolescent patients do not know about e-cigarettes”; “Discussing e-cigarettes with patients may encourage them to use e-cigarettes”; “It is important to discuss e-cigarettes with adolescent patients”; and “Parents of adolescents need to know about e-cigarettes”). An additional item used the same response scale to assess desire for education about e-cigarettes (“I would like to learn more about e-cigarettes”). The survey also gathered demographic and practice characteristics, including provider type (family medicine physician, pediatrician, or nurse practitioner), year of training completion, type and location of primary clinical practice, and number of adolescent patients (ages 11–17 years) seen per week.

Analysis

We examined univariate characteristics of the three main dependent variables (awareness of, knowledge of, and comfort discussing e-cigarettes), as well as correlations of these variables with providers’ age. We used one-way ANOVA to test for differences in the three dependent variables by provider type. We treated two highly correlated risk perception items (“E-cigarettes are safer to use than regular cigarettes” and “E-cigarettes are safer to use than smokeless tobacco [chew, snuff, dip, etc.]”) as a scale (Cronbach’s α = .92) and examined correlations of the scale with beliefs about the importance of discussing e-cigarettes with patients and their parents. Missing values were imputed to the mean in order to retain the maximum sample size. Results of the analysis did not differ when these observations were excluded. We analyzed data with Stata v.12 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). All reported results are significant based on two-tailed statistical tests with a critical alpha of .05.

Results

Most providers were female (71%) and practiced in a suburban setting (42%) (Table 1). Respondents included family medicine physicians (46%), pediatricians (20%), and nurse practitioners (34%). The average age was 48 years (SD 11 years), and most providers (59%) completed their clinical training prior to 2000.

Table 1.

Provider and practice characteristics (n = 561)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.8 (10.5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 400 (71.3) |

| Male | 161 (28.7) |

| Provider type | |

| Family medicine physician | 258 (46.0) |

| Pediatrician | 114 (20.3) |

| Nurse practitioner | 189 (33.7) |

| Year of residency or clinical training completion | |

| 1989 or earlier | 144 (25.7) |

| 1990–1999 | 185 (33.0) |

| 2000–2009 | 157 (28.0) |

| 2010 or later | 64 (11.4) |

| Missing | 11 (2.0) |

| Practice type | |

| Private independent practice | 181 (32.3) |

| Practice network/HMO | 169 (30.1) |

| Hospital or medical center | 117 (20.9) |

| Other | 94 (16.8) |

| Practice location | |

| Urban | 165 (29.4) |

| Suburban | 234 (41.7) |

| Rural | 162 (28.9) |

| Number of adolescent patients seen per week | |

| 1–10 | 277 (49.4) |

| 11–25 | 220 (39.2) |

| 26 or more | 64 (11.4) |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

E-cigarette awareness and knowledge

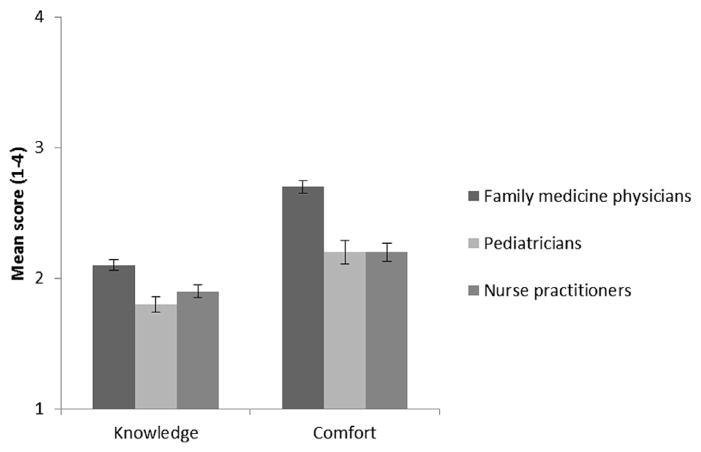

Nearly all providers (92%) had heard of e-cigarettes (Table 2). Older providers were less likely to have heard of e-cigarettes (r = −.08) compared with younger providers. Family medicine physicians were more likely to be aware of e-cigarettes than either pediatricians or nurse practitioners (97% vs. 88% and 88% respectively, F (2, 558) = 6.80). Among providers who were aware of e-cigarettes (n = 516), the most frequently reported sources of information were patients (62%), news stories (39%), and advertisements (37%) (Figure 1). A substantial minority of providers reported having heard of e-cigarettes through professional sources (24%) and colleagues (11%). More than one in ten respondents (11%) reported treating at least one adolescent patient who had used e-cigarettes.

Table 2.

Providers’ knowledge, comfort, and desire to learn about e-cigarettes (n = 561)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Aware of e-cigarettes | |

| Yes | 516 (92.0) |

| No | 45 (8.0) |

| Cared for an adolescent patient who has used an e-cigarette | |

| Yes | 62 (11.1) |

| No | 499 (88.9) |

| Self-reported knowledge about e-cigarettesa | |

| Nothing at all | 95 (18.4) |

| A little | 334 (64.7) |

| A moderate amount | 78 (15.1) |

| Quite a lot | 9 (1.7) |

| Comfort talking to a patient about e-cigarettesa | |

| Very uncomfortable | 86 (16.7) |

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 187 (36.2) |

| Somewhat comfortable | 184 (35.7) |

| Very comfortable | 59 (11.4) |

| Would like to learn more about e-cigarettesb | |

| Strongly disagree | 19 (3.5) |

| Somewhat disagree | 45 (8.3) |

| Somewhat agree | 232 (42.6) |

| Strongly agree | 249 (45.7) |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Among providers who were aware of e-cigarettes (n = 516).

Among all providers who answered this item (n = 545).

Figure 1.

Percent of providers who have heard of e-cigarettes through various sources. Professional sources include journal articles and newsletters.

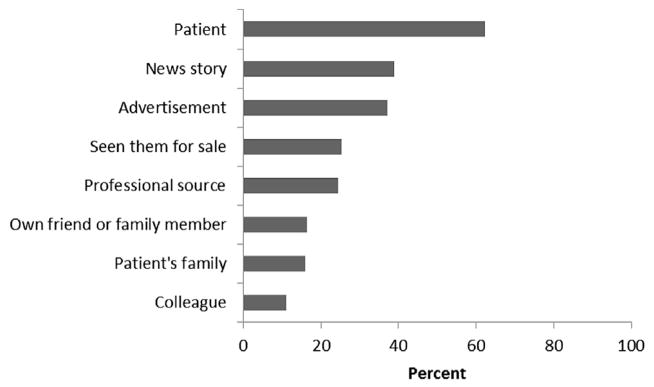

Of providers who had heard of e-cigarettes, 83% reported that they knew “a little” or “nothing at all” about e-cigarettes. More than half of providers (53%) who had heard of e-cigarettes were either “somewhat” or “very” uncomfortable talking to patients about them. Self-reported knowledge about e-cigarettes did not vary by provider’s age, but provider’s age was positively associated with comfort discussing e-cigarettes with a patient (r =.09). Family medicine physicians reported knowing more about e-cigarettes than either pediatricians or nurse practitioners (means 2.1 vs. 1.8 and 1.9 respectively, F (2, 513) = 13.6) (Figure 2). Family medicine physicians were also more comfortable discussing cigarettes than either pediatricians or nurse practitioners (means 2.7 vs. 2.2 and 2.2 respectively, F (2, 513) = 22.6). Interest in learning more about e-cigarettes among all providers in the sample was high (mean 3.3, SD .8); the vast majority (88%) either “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed that they would like learn more.

Figure 2.

Differences by provider type in self-reported knowledge of and comfort with discussing e-cigarettes. Error bars represent standard errors.

E-cigarette risk beliefs and communication

On average, providers moderately agreed with a combined measure indicating that e-cigarettes are safer than regular cigarettes and smokeless tobacco (mean 2.7, SD .8). However, providers expressed considerable concern that e-cigarettes could be a gateway to other tobacco use (mean 3.0, SD .8) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Providers’ beliefs about e-cigarette risks and communication (n = 561)

| Mean (SD) | Strongly disagree % | Somewhat disagree % | Somewhat agree % | Strongly agree % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk beliefs | |||||

| E-cigarettes are safer to use than regular cigarettes | 2.7 (.9) | 12.7 | 21.8 | 52.1 | 13.4 |

| E-cigarettes are safer to use than smokeless tobacco (chew, snuff, dip, etc.) | 2.7 (.9) | 12.9 | 22.7 | 49.6 | 14.8 |

| E-cigarettes could be a “gateway” to other tobacco use | 3.0 (.8) | 5.5 | 19.4 | 43.0 | 32.1 |

| Communication | |||||

| My adolescent patients do not know about e-cigarettes | 2.1 (.7) | 21.7 | 54.4 | 20.6 | 3.3 |

| Discussing e-cigarettes with patients may encourage them to use e-cigarettes | 1.8 (.8) | 45.3 | 36.6 | 15.5 | 2.6 |

| It is important to discuss e-cigarettes with adolescent patients | 2.8 (.7) | 4.1 | 26.9 | 55.1 | 13.9 |

| Parents of adolescents need to know about e-cigarettes | 3.3 (.7) | 1.9 | 9.1 | 51.0 | 38.0 |

Providers moderately disagreed that their adolescent patients “do not know” about e-cigarettes (mean 2.1, SD .7). Few providers were concerned that discussing e-cigarettes with their adolescent patients would encourage use (mean 1.8, SD .8), and many providers “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed that it is important to discuss e-cigarettes with their adolescent patients (mean 2.8, SD .7) and with patients’ parents (mean 3.3, SD .7).

Providers who believed that e-cigarettes were safer than other tobacco products were less likely to feel it was important to discuss e-cigarettes with patients (r = −.21) or parents of patients (r = −.18). Those who had stronger beliefs that e-cigarettes could serve as a gateway to other tobacco use were more likely to feel it was important to discuss e-cigarettes with patients (r = .29) and parents (r = .31).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine healthcare providers’ awareness of and attitudes about e-cigarettes and adolescents, an important emerging public health concern given the dramatic increase in use of e-cigarettes by U.S. adolescents between 2011 and 2012 [8]. Our findings suggest nearly all providers had heard of e-cigarettes, but most had learned about them from anecdotal sources such as patients, news stories, and advertisements, rather than through professional avenues. The proportion of providers reporting having treated at least one adolescent patient who had tried e-cigarettes was relatively high and is likely to get higher if the prevalence of use continues to increase in this population [8]. Further, we found that providers reported moderately low levels of knowledge and comfort discussing e-cigarettes, a possible barrier to providing education and guidance to adolescent patients and their parents despite providers’ beliefs about the importance of doing so.

In this study, nearly two thirds of providers had heard about e-cigarettes from patients, more than any other source. Information from adolescent patients may be inaccurate or biased, and providers may then pass on this misinformation to other patients. Further, this finding suggests the critical need for providers to receive more education from unbiased, professional sources about the state of the science regarding e-cigarettes.

Younger providers in our sample had higher levels of awareness of e-cigarettes. This finding is consistent with national U.S. data showing that younger adults are somewhat more likely to have heard of e-cigarettes than older adults [17,18]. This greater level of awareness among younger healthcare providers did not translate into greater comfort discussing e-cigarettes with patients; rather, comfort discussing e-cigarettes increased with age. Because older providers are likely to have more years of clinical experience, they may simply be more comfortable discussing any risk-related topic with patients.

Compared with nurse practitioners and pediatricians, family medicine physicians had higher levels of e-cigarette awareness. They also rated themselves as more knowledgeable of and comfortable with discussing e-cigarettes compared with other provider types. Other research also finds differences in adolescent tobacco screening and counseling by provider training specialty. For example, compared with pediatricians, family physicians screen more of their adolescent patients for tobacco use [19] and provide adolescents with more of the smoking prevention and cessation services recommended by preventive services guidelines [11]. These differences may reflect the fact that family medicine physicians routinely serve adult, as well as pediatric, patient populations. Indeed, in our sample, family medicine physicians reported serving fewer adolescents than either nurse practitioners or pediatricians. In general, healthcare providers are more likely to screen and counsel adult patients about tobacco use than to provide these services to adolescents [20]. Thus the experience that family medicine physicians have with screening and counseling adults could translate to higher levels of self-efficacy to provide tobacco counseling routinely to all of their patients, including adolescents.

Although they were concerned about the possibility that adolescents might use e-cigarettes as a gateway to other tobacco use, most providers believed that e-cigarettes were at least somewhat less harmful than regular cigarettes or smokeless tobacco. The current scientific evidence about the dangers of e-cigarettes is mixed. E-cigarettes may ultimately prove to be less harmful than regular cigarettes simply because they do not produce the same dangerous combustion by-products [21], but there is concern about the use of propylene glycol as a humectant [22], as well as significant variation in the toxicity of the “e-liquid” (the combination of humectant, nicotine, and flavoring inside an e-cigarette cartridge) [4]. For example, Goniewicz and colleagues analyzed the vapor generated from 12 models of e-cigarettes and found that NNK (one of a family of carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines) was detectable in some, but not all, models [23]. Furthermore, given that nicotine dependence develops quickly [24], even occasional use of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes could potentially lead to use of regular tobacco cigarettes and exposure to the resulting combustion by-products.

Physicians and nurse practitioners who expressed greater concern about e-cigarettes being a gateway to tobacco use were more likely to feel it was important to discuss e-cigarettes with patients and parents of patients. Taken together, these findings suggest that disseminating information as it becomes available about e-cigarette safety and the use of the product as an introduction to nicotine will be important for motivating providers’ preventive counseling efforts. Existing practice guidelines, such as Bright Futures, recommend that general comprehensive exams include asking all adolescents about tobacco use and counseling them not to smoke or use tobacco [9]. Past research suggests that behavioral counseling interventions can effectively reduce the risk of youth smoking initiation [13].

Physicians and nurse practitioners who provide primary care to adolescents have an opportunity to educate patients about e-cigarette use. The moderate levels of self-reported knowledge about e-cigarettes and the sizeable proportion of providers who reported being uncomfortable discussing e-cigarettes suggest that, at present, it would be challenging for clinicians to provide this education. Although providers have limited time to provide anticipatory guidance about risk during already busy clinical encounters, knowledge about e-cigarettes could be valuable to providers if they are specifically asked about them by patients. That patients were a primary source of information about e-cigarettes suggests that this topic is already arising during conversations with patients.

Study limitations include a cross-sectional design and a low response rate, which may lead to nonresponse bias. However, the timely investigation of an emerging health issue, the use of a large statewide sample, and the diversity of respondents across specialty and number of years in practice are strengths of this study. Generalizability to other types of healthcare providers and to providers in other areas will need to be established. In addition, although the survey items were developed with input from clinicians, this early work on provider perceptions of e-cigarettes was not guided by a theoretical framework and did not include questions about the use of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation tool, an important ongoing research issue. Further, because of the lack of scientific consensus about the properties and use of e-cigarettes, we were only able to measure perceived, rather than actual, knowledge. As the body of research on e-cigarettes grows, future studies should examine providers’ actual knowledge about e-cigarette safety, chemical constituents, and prevalence of use.

Given that nearly 7% of middle and high school students had ever tried e-cigarettes in 2012 and 2% used them on an ongoing basis [8], providers will likely be called upon to incorporate screening and counseling about e-cigarettes into existing, routine preventive services for adolescents. In order to do so, it will be critical not only to increase providers’ knowledge about e-cigarettes but also their comfort with and self-efficacy for discussing this topic with patients. Self-efficacy to deliver preventive services is both a significant correlate of providers’ tobacco screening and counseling and a modifiable target in past interventions that have successfully increased provision of these services to adolescents [25,26]. Education about e-cigarettes could help providers, especially those who see a large proportion of adolescents but have low knowledge about or comfort discussing e-cigarettes, deliver comprehensive prevention services to adolescents at risk of tobacco use.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

In this statewide sample, healthcare providers reported moderately low levels of knowledge about and comfort discussing electronic cigarettes with adolescent patients; nearly all wished to learn more. Findings highlight information gaps that may be a barrier to providing comprehensive prevention services to adolescents at risk of tobacco use.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded through a 2012 Young Investigator Award from the Academic Pediatric Association, supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Federal Grant U04MC07853-03). The study was further supported by a NRSA in Primary Medical Care from HRSA (T32HP22239, PI: Borowsky); UNC Lineberger Cancer Control Education Program (R25 CA57726); and Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant support (UL1RR033183) to the University of Minnesota from the National Center for Research Resources. The authors thank Rachel Eggert for her assistance with planning and conducting the survey.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Ayers JW, Ribisl KM, Brownstein JS. Tracking the rise in popularity of electronic nicotine delivery systems (electronic cigarettes) using search query surveillance. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions, and beliefs: A systematic review. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westenberger BJ. Evaluation of E-Cigarettes. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2009. [Accessed on September 30, 2013]. DPATR-FY-09–23. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/Scienceresearch/UCM173250.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahl V, Lin S, Xu N, et al. Comparison of electronic cigarette refill fluid cytotoxicity using embryonic and adult models. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;34:529–37. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed on September 30, 2013];Regulation of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products. 2011 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm252360.htm.

- 6.Grana RA. Electronic cigarettes: A new nicotine gateway? J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:135–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepper JK, Reiter PL, McRee AL, et al. Adolescent males’ awareness of and willingness to try electronic cigarettes. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corey C, Wang B, Johnson SE, et al. Electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:729–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagan J, Shaw J, Duncan P, editors. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. 3. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Medical Association. Guidelines for adolescent preventive services (GAPS): Recommendation monograph. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein JD, Levine LJ, Allan MJ. Delivery of smoking prevention and cessation services to adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:597. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulig JW. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: The role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;115:816–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozer EM, Adams SH, Orrell-Valente JK, et al. Does delivering preventive services in primary care reduce adolescent risky behavior? J Adolesc Health. 2011;49:476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 6. Lenexa, KS: AAPOR; 2009. Response Rate 4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, et al. Awareness and ever use of electronic cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1623–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, et al. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in U.S. adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1758–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellen JM, Franzgrote M, Irwin CE, Jr, et al. Primary care physicians’ screening of adolescent patients: A survey of California physicians. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:433–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIlvain HE, Crabtree BF, Gilbert C, et al. Current trends in tobacco prevention and cessation in Nebraska physicians’ offices. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benowitz NL. Smokeless tobacco as a nicotine delivery device: Harm or harm reduction? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:491–3. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varughese S, Teschke K, Brauer M, et al. Effects of theatrical smokes and fogs on respiratory health in the entertainment industry. Am J Ind Med. 2005;47:411–8. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Tob Control. 2013. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob Control. 2000;9:313–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozer EM, Adams SH, Gardner LR, et al. Provider self-efficacy and the screening of adolescents for risky health behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zapka JG, Fletcher K, Pbert L, et al. The perceptions and practices of pediatricians: Tobacco intervention. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e65. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]