Abstract

PURPOSE

To evaluate the safety and effect on visual function of ciliary neurotrophic factor delivered via an intraocular encapsulated cell implant for the treatment of retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

DESIGN

Ciliary neurotrophic factor for late-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 3 (CNTF3; n = 65) and ciliary neurotrophic factor for early-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 4 (CNTF4; n = 68) were multicenter, sham-controlled dose-ranging studies.

METHODS

Patients were randomly assigned to receive a high- or low-dose implant in 1 eye and sham surgery in the fellow eye. The primary endpoints were change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at 12 months for CNTF3 and change in visual field sensitivity at 12 months for CNTF4. Patients had the choice of retaining or removing the implant at 12 months for CNTF3 and 24 months for CNTF4.

RESULTS

There were no serious adverse events related to either the encapsulated cell implant or the surgical procedure. In CNTF3, there was no change in acuity in either ciliary neurotrophic factor–or sham-treated eyes at 1 year. In CNTF4, eyes treated with the high-dose implant showed a significant decrease in sensitivity while no change was seen in sham- and low dose–treated eyes at 12 months. The decrease in sensitivity was reversible upon implant removal. In both studies, ciliary neurotrophic factor treatment resulted in a dose-dependent increase in retinal thickness.

CONCLUSIONS

Long-term intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor is achieved by the encapsulated cell implant. Neither study showed therapeutic benefit in the primary outcome variable.

Retinitis pigmentosa (rp) affects approximately 100,000 Americans.1 It is a group of retinal degenerative diseases that have a complex molecular etiology.2 More than 100 mutations in several genes, including rhodopsin (RHO), peripherin (PRPH2), and PDEβ, are believed to be responsible for RP, although the genotypes of the majority of RP patients are unknown. Despite the genetic heterogeneity, patients typically experience decreased night vision early in life attributable to the loss of rod photoreceptors.1 While the genetic defects primarily affect rods, progressive outer retinal degeneration leads to progressive visual field loss and, ultimately, severe visual disability. Since the molecular cause underlying the retinal degeneration is not known for most patients, an approach to slow progressive loss of photoreceptors that is effective for many different genetic forms of inherited retinal degeneration would have broad applicability.

The promise of growth factors as potential therapeutics for photoreceptor degeneration was first demonstrated in 1990.3 Since then, many growth factors, neurotrophic factors, and cytokines have been tested in a variety of photoreceptor degeneration models, mainly by intravitreal injection of purified recombinant proteins in short-term experiments.4,5 Among them, ciliary neurotrophic factor has been shown to be the most effective in numerous animal models.5 However, the chronic nature of RP (years to decades) and the short-term effectiveness of purified recombinant ciliary neurotrophic factor make repetitive intraocular injections impractical.

One of the major challenges in the treatment of RP is the safe and effective local delivery of therapeutic macromolecules to the retina. The encapsulated cell technology implant (NT-501; Neurotech USA, Lincoln, Rhode Island, USA) was designed specifically to address this challenge. The encapsulated cell technology implant enables the controlled, continuous, and long-term delivery of therapeutic macromolecules, including neurotrophic factors, directly into the vitreous cavity inside the eye. In addition, encapsulated cell implants can be retrieved, thus providing an additional level of safety.

Ciliary neurotrophic factor decreases photoreceptor loss during retinal degeneration.3–5 Although its intrinsic function is not fully understood, exogenous ciliary neurotrophic factor affects the survival and differentiation of cells in the nervous system, including retinal cells.6–8 It effectively protected photoreceptors in 12 animal models of photoreceptor degeneration.4,5,9–11 Further, ciliary neurotrophic factor has passed appropriate milestones in a phase 1 human clinical study of RP.12 The key question for patients and clinicians is whether it can be used safely in the treatment of retinal degeneration in humans.

Two phase 2 studies were designed to demonstrate the safety profile of NT-501 in patients with early and more advanced RP, to evaluate the effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal structure and function, and to evaluate dose and primary endpoints for future studies. The primary endpoints selected here were change in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at 12 months for ciliary neurotrophic factor for late-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 3 (CNTF3) and change in visual field sensitivity at 12 months for ciliary neurotrophic factor for early-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 4 (CNTF4).

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

A total of 65 and 68 patients were enrolled at 13 sites in the United States for the CNTF3 and CNTF4 studies, respectively (Table 1). Approvals were received from the National Institutes of Health Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and from the Institutional Review Board and Institutional Biosafety Committee at each site prior to enrollment. The Institutional Review Boards responsible for these studies are listed in the acknowledgment at the end of this article. Subjects signed written informed consent before determination of their full eligibility.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Receiving Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Retinitis Pigmentosa

| CNTF3

|

CNTF4

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Dose | High Dose | Low Dose | High Dose | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 14 (63.3%) | 20 (46.5%) | 10 (50.0%) | 23 (47.9%) |

| Female | 8 (36.4%) | 23 (53.5%) | 10 (50.0%) | 25 (52.1%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 18 (81.8%) | 37 (86.0%) | 18 (90.0%) | 47 (97.9%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 19 (86.4%) | 41 (95.3%) | 20 (100.0%) | 44 (91.7%) |

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.1 (10.5) | 42.0 (11) | 34.9 (12) | 40.2 (11.8) |

| Median | 41.0 | 43.0 | 36.0 | 41.5 |

| Range | 24–59 | 18–67 | 18–58 | 18–59 |

| Implant/Sham | Implant/Sham | Implant/Sham | Implant/Sham | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCVA | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 45.5 (11.2)/44.8 (10.4) | 45.0 (10.4)/46.7 (9.1) | 79.2 (7.5)/78.9 (7.2) | 78.9 (6.9)/78.7 (6.4) |

| Median | 45.9/46.1 | 44.9/46.8 | 81.0/78.8 | 79.5/79.5 |

| Range | 25–64/24–65 | 25–65/26–62 | 63–91/63–91 | 59–90/66–92 |

| Total mac vol (mm3) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.0 (0.8)/6.0 (0.7) | 6.2 (1.0)/6.3 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.3)/6.4 (1.4) | 6.3 (0.8)/6.3 (0.8) |

| Median | 6.1/6.0 | 6.0/6.1 | 6.1/6.4 | 6.2/6.2 |

| Range | 4.7–8.2/4.7–7.9 | 4.3–9.1/4.5–9.3 | 4.5–10.6/4.7–11.2 | 5.1–8.3/4.9–8.4 |

| Electroretinogram (μV)a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.32 (2.8)/8.26 (3.1) | 14.3 (3.0)/12.7 (3.0) | 15.4 (2.3)/17.2 (2.4) | 22.2 (2.4)/22.4 (2.5) |

| Median | 8.2/8.0 | 13.8/10.9 | 15.0/21.0 | 21.5/21.9 |

| Range | 2.6–65.3/1.8–58.3 | 3.0–84.0/3.3–88.2 | 3.6–65/3.7–52 | 5.4–149/3.9–157 |

| Visual field sensitivity (dB) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 332 (502)/323 (494) | 423 (488)/444 (496) | 1142 (446)/1136 (424) | 1007 (429)/998 (466) |

| Median | 202/175 | 210/209 | 1053/1095 | 965/966 |

| Range | 31–2307/17–2247 | 5–1996/2–1940 | 538–1885/526–1875 | 340–2176/220–2276 |

BCVA = best-corrected visual acuity (letters read by Electronic Visual Acuity); CNTF3 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for late-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 3; CNTF4 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for early-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 4; Mac vol = macular volume.

White flash – Amplitude.

Each participant’s clinical diagnosis was consistent with retinitis pigmentosa.

The CNTF3 study–specific inclusion criteria included: age 18–68 years, BCVA of 20/63–20/320 (Snellen equivalent determined with the use of an Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study [ETDRS] chart), and absence of cystoid macula edema (CME) as judged by time-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT). The CNTF4 study–specific inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18–65 years with BCVA of 20/63 or better. Patients with CME were permitted. Each eye had a mean sensitivity deviation of at least 6 dB loss of static perimetric sensitivity, on average, throughout the central 60-degree-diameter field (including non-zero points). Each eye sensitivity was to have a nonzero value for at least 30 locations, and the horizontal field extent was to be 20 degrees or greater as tested on a Humphrey field analyzer (HFAII) 30–2 test with a Goldmann V target size. The eligibility of subjects was confirmed by an independent central reading center according to standardized criteria with trained fundus photograph and OCT graders who were masked to subjects’ treatment assignment.

Safety visits were conducted at 1 day, 1 week, and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Blood draws for laboratory safety studies, including serum antibodies, were obtained on each visit. The primary efficacy endpoints, change in BCVA and change in visual field sensitivity, were prespecified at 12 months post implant for CNTF3 and CNTF4, respectively. Patients received either high- or low-dose NT-501 implants in 2:1 ratio in 1 eye, and a sham treatment in the fellow eye. The high dose was selected based on the dose-response effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor in the rcd1 model of retinal degeneration11 and was the maximum effective dose. The low dose was 50% of the minimum effective dose in the rcd1 dog model.

The original trial design approved by the FDA specified that implants be removed at 12 months (CNTF3) or 24 months (CNTF4). After the initiation of the trial, the FDA recommended that patients retain the implants at the end of the study (avoiding a second surgery). Since all patients had consented to have their implants removed at the end of the study, they were offered a choice either to keep the implant in place or to have the implant removed. For each study, patients were followed for an additional 6 months (a total of 18 months follow-up for CNTF3 and 30 months for CNTF4). At the conclusion of the trial, 16 patients in the high-dose CNTF4 study (10 with the implant in place and 6 with the implant removed) consented to a registry study with an additional year of follow-up (42 months). Those with the implant removed were also tested at 54 months.

BCVA was measured by an electronic visual acuity tester (EVA) using the ETDRS protocol.13 BCVA in CNTF3 was measured twice per eye on each of 3 baseline visits. Baseline 1 BCVA was used to qualify subjects and baseline 2 and 3 BCVA (average of 4 measures per eye) was used as baseline BCVA. Three BCVA measurements were taken for each subsequent visit and the average of the 3 BCVA values was used to assess the change from baseline.

Visual field sensitivity in CNTF4 was measured with the 30–2 grid using the Humphrey visual field analyzer. Visual field sensitivity was measured twice per eye on each of 3 baseline visits. Eligibility for enrollment was determined by the results of baseline 1. The average value of the 4 baseline 2 and baseline 3 examinations, each representing the sum of actual thresholds for all 76 locations, provided the baseline visual field sensitivity. Four visual field sensitivity measurements per eye were taken for each subsequent visit and the average of the 4 visual field sensitivity sums was used to assess the change from baseline. Pupil diameter was measured within the Humphrey visual field analyzer at the conclusion of each test session.

Full-field electroretinograms (ERGs) were measured at baseline and at 12 months. The procedure adhered to International Society of Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision standards, but was limited to light-adapted (30 Hz flicker and single-flash) responses.

Retinal thickness and morphology were evaluated by OCT. The fast macular thickness map protocol, a 7-mm horizontal line scan, and 6-mm vertical line scan were obtained with the Stratus OCT and software version 4.0 or higher (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, Dublin, California, USA). OCT images were collected by certified technicians. The images were evaluated by masked readers at the Duke University OCT Reading Center and analyzed for average thickness at center point, total macular volume, and average thickness in 9 subfields. Pathologic findings, such as cysts, epiretinal membrane, vitreomacular traction, and choroidal neovascularization, were also recorded and analyzed.

A subset of all high-dose CNTF4 patients (n = 10) from a single center (Dallas, Texas, USA) were evaluated on the 12-month visit by spectral-domain OCT (Spectralis HRA + OCT; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). The images of horizontal midline scans were exported to data-analysis software (Igor Pro; WaveMetrics, Inc, Portland, Oregon, USA) and segmented to identify the Bruch membrane/choroid boundary, the ellipsoid zone (inner/outer segment border), and the inner nuclear layer/outer plexiform layer boundary. Using the locations of these boundaries, a masked reader defined the receptor outer segment plus retinal pigment epithelium (OS+) as the distance between the ellipsoid zone and Bruch membrane/choroid boundaries.14 The outer nuclear layer was the distance between the inner nuclear layer/outer plexiform layer and ellipsoid zone boundaries. In order to avoid possible complications from CME, segment thicknesses were determined 1.7 mm (6 degrees) nasal and temporal to the fovea and compared between high-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor–implanted and sham-treated eyes. Since spectral-domain OCT scans were not available at baseline, comparisons were between the implanted and sham eyes at 12 months.

STUDY TREATMENT

The ciliary neurotrophic factor–secreting, encapsulated cell implants, designated NT-501, are 6 mm long with 1 mm diameter and are constructed of a semi-permeable polymer outer membrane. The low-dose implants released 5 ng/day and the high-dose implant released 20 ng/day prior to implant.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The efficacy analysis was performed on an intent-to-treat basis among all subjects. Since all subjects completed the study as planned, the last-observation-carried-forward method for missing data was not used. For change in BCVA, ERG, and visual field sensitivity, the within-group and between-group comparisons were based on a paired t test. Clinical response rates were compared between groups using a 2-sided Fisher exact test. For retinal thickness change as measured by OCT, the overall comparison among treatment medians was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Pair-wise differences between treatment medians were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

EVALUATION OF ENCAPSULATED CELL IMPLANTS AFTER REMOVAL

Immediately upon removal, the devices were placed into Endo-SFM conditioned medium (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) at 37 C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity for 24 hours. The rate of ciliary neurotrophic factor secretion was determined using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).

RESULTS

STUDY PATIENTS

Between January 8, 2007 and October 31, 2007, 65 patients and 68 patients were enrolled into the CNTF3 and CNTF4 studies, respectively, and were randomly assigned to study treatment. Groups were balanced for demographic and baseline ocular characteristics (Table 1). All patients completed the 12-month primary endpoint follow-up and no patients dropped out of the study.

SAFETY PROFILE

Cumulative adverse events for the 12-month study period (CNTF3 and CNTF4) are summarized in Table 2. The most frequent adverse event was miosis, measured on the Humphrey field analyzer in 25.6% of CNTF3 and 31.3% of CNTF4 patients assigned to receive the high-dose implant. Unequal pupil sizes were also reported by many of these patients. Although neither the field technicians nor the patients knew whether the implant was causing miosis or dilation, the unequal pupil sizes could possibly have interfered with masking. No serious adverse events related to the NT-501 implant or surgical procedures were reported during the 12-month study period. No treatment-related severe adverse effects, including retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, intraocular pressure (IOP) increase, or choroidal neovascularization (CNV), were reported. Neither ciliary neurotrophic factor nor antibodies against it was detected in the serum. Likewise, no antibodies against the encapsulated cells were detected.

TABLE 2.

Adverse Events at 12 Months in Patients Receiving Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Retinitis Pigmentosa

| Adverse Events/Eye Disorders | CNTF3

|

CNTF4

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Dose (n = 22) | High Dose (n = 43) | Low Dose (n = 20) | High Dose (n = 48) | |

| Intraocular pressure increasea | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Eye hemorrhageb | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Photopsia | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (8.3%) |

| Miosis | 1 (4.5%) | 11 (25.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (31.3%) |

| Cataractc | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.2%) |

| Choroidal neovascularization | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Wound leaks or erosion | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Endophthalmitis | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Implant extrusion | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Retinal detachment | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

CNTF3 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for late-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 3; CNTF4 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for early-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 4.

Intraocular pressure increase (24–31 mm Hg) usually lasted a few days to a few weeks and pressure returned to normal at the next scheduled visit without medical intervention.

Related to the surgical wound and recovered with no sequelae within 10 days.

Worsening of a pre-existing cataract (mild).

VISUAL ACUITY CHANGES

No significant changes in visual acuity were observed in ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated or sham-treated eyes in CNTF3 and CNTF4 patients (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Summary of Changes From Baseline at 12 Months in Patients Receiving Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Retinitis Pigmentosa

| Endpoint | CNTF3

|

CNTF4

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Dose Implant/Sham | High-Dose Implant/Sham | Low-Dose Implant/Sham | High-Dose Implant/Sham | |

| Change in best-corrected visual acuity | ||||

| Month 12 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | −2.9 ± 11.3/−2.3 ± 12 | −1.3 ± 9.6/−3.2 ± 10.5 | −0.5 ± 5.0/0.5 ± 4.7 | 0.7 ± 4.1/1.0 ± 4.6 |

| Range | −48-11/−47-11 | −25-14/−45-15 | −16-7/−15-6 | −7–12/−9–11 |

| P value | .650 | .275 | .497 | .646 |

| Change in total macular volume (mm3) | ||||

| Month 12 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.09 ± 0.23/−0.05 ± 0.17 | 0.23 ± 0.58/−0.02 ± 0.18 | 0.22 ± 0.21/−0.05 ± 0.38 | 0.43 ± 0.37/−0.05 ± 0.27 |

| Range | −0.4-0.4/−0.5-0.2 | −1.2–2.2/−0.5-0.3 | −0.2–0.7/−1.2-0.8 | −0.3–1.7/−1.3-0.8 |

| P value | .148 | <.001 | .001 | <.001 |

| Change in electroretinogram (μV) (geometric means) | ||||

| Month 12 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.10 ± 1.5/0.99 ± 1.48 | 0.78 ± 1.5/0.89 ± 1.73 | 1.03 ± 1.62/0.99 ± 1.48 | 0.79 ± 1.52/0.87 ± 1.73 |

| Range | 0.5–2.9/0.6–2.3 | 0.2–1.4/0.1–2.1 | 0.4–2.9/0.6–2.3 | 0.2–1.4/0.1–2.1 |

| P value | .347 | .129 | .776 | .242 |

| Change in Humphrey visual field sensitivity (dB) | ||||

| Month 12 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.1 ± 109.5/4.7 ± 101.4 | −98.4 ± 165.3/−14 ± 101.5 | 1.4 ± 174.6/16.8 ± 165.4 | −164.3 ± 114.6/−67.1 ± 104.2 |

| Range | −172–282/−213–374 | −487-242/−294-286 | −265–354/−191–423 | −489–95/−322–152 |

| P value | .97 | .001 | .137 | <.001 |

CNTF3 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for late-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 3; CNTF4 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for early-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 4.

VISUAL FIELD SENSITIVITY CHANGES

Change for total sensitivity is summarized in Table 3. For both CNTF3 and CNTF4 studies, there was a decrease in visual field sensitivity in the high dose–treated eyes that was significantly greater than in the sham-treated eyes at 12 months. There were no changes in visual field sensitivity in the low-dose eyes relative to sham eyes (Table 3). In the CNTF4 study, there was a statistically significant decrease in visual field sensitivity in the high dose–treated eyes compared with the sham-treated eyes at the 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months postimplantation period (Table 4, P < .001). However, at 6 months after implant removal, there was no difference in visual field sensitivity change in the eyes treated with high-dose implant compared with sham-treated (Table 4, P = .071).

TABLE 4.

Change in Humphrey Visual Field Total Sensitivity (dB) From Baseline in Patients Receiving Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Retinitis Pigmentosa

| Endpoint | Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor for Early-Stage Retinitis Pigmentosa Study 4

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Low-Dose Implant/Sham | High-Dose Implant/Sham | |

| Month 6 | n = 20 | n = 47 |

| Mean (SD) | −1.21 ± 140.1/25.8 ± 128.3 | −135.2 ± 107.8/−43 ± 82.9 |

| Range | −289, 260/−199, 323 | −510, 80.8/−260, 176 |

| P value | .07 | <.001 |

| Month 12 | n = 20 | n = 47 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 ± 174.6/16.8 ± 165.4 | −164.3 ± 114.6/−67.1 ± 104.2 |

| Range | −265, 354/−191, 423 | −489, 95/−322, 152 |

| P value | .137 | <.001 |

| Month 18 | n = 20 | n = 46 |

| Mean (SD) | −62.5 ± 208.6/−37.3 ± 173.5 | −202.3 ± 137.1/−98.7 ± 127.1 |

| Range | −453, 490/−324, 368 | −684, 26.5/−643, 121 |

| P value | .064 | <.001 |

| Month 24 | n = 20 | n = 47 |

| Mean (SD) | −104.2 ± 195/−72.1 ± 163 | −227.9 ± 150/−137 ± 127 |

| Range | −468, 231/−435, 214 | −720, 11.3/−688, 91.5 |

| P value | .016 | <.001 |

| Month 30 | n = 12 | n = 25 |

| Mean (SD) | −47 ± 346/−58.6 ± 275 | −321.7 ± 197/−211.8 ± 145 |

| Range | −519, 910/−531, 635 | −838, −10.3/−580, 44.3 |

| P value | .676 | <.001 |

| 6 months post explant | n = 6 | n = 20 |

| Mean (SD) | −82.7 ± 185.6/−58.5 ± 148.6 | −188.6 ± 122.3/−144.6 ± 134.3 |

| Range | −316, 207/−232, 193 | −537.5, −18.5/−583.3, 63.8 |

| P value | .416 | .071 |

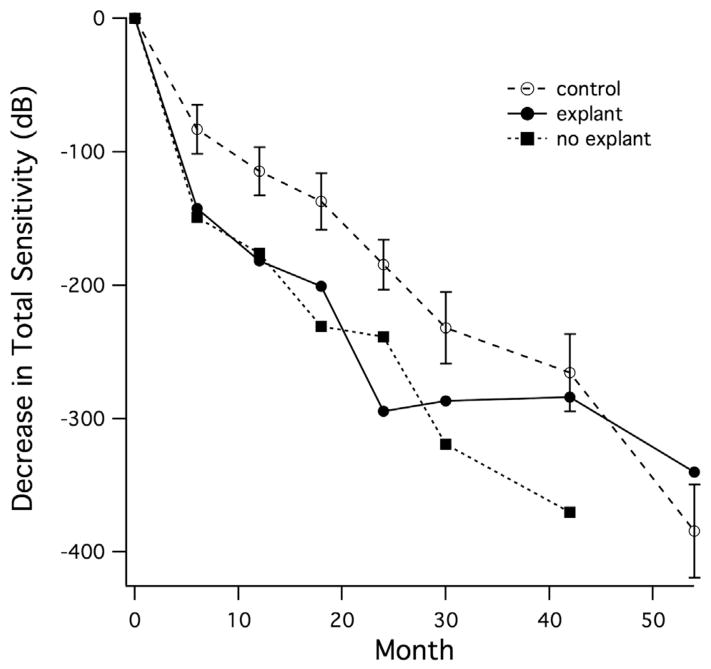

Decrease in total sensitivity relative to baseline is shown in Figure 1 for the 16 patients from CNTF4 who consented to post-30-month visual field testing. Similar to the larger group, eyes retaining the implant (n = 10) showed greater loss of sensitivity than control eyes, starting at 6 months and persisting through 42 months. Eyes with the implant removed (n = 6) showed little additional sensitivity loss after the explant and showed less total sensitivity loss than the control eyes at 54 months.

FIGURE 1.

Mean decrease in total Humphrey visual field sensitivity over time in a subset of patients with retinitis pigmentosa participating in the registry study (up to 54 months follow-up). All patients received the high-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor implant in 1 eye. Six patients chose to have the implant removed at 24 months (explant); 10 patients chose to retain the implant (no explant).

ELECTRORETINOGRAM

Light-adapted 31 Hz flicker amplitude and implicit time were evaluated. No significant changes in ERG amplitude were observed at 12 months compared with the baseline in any of the treatment groups (Table 3).

RETINAL STRUCTURAL CHANGES AT 12 MONTHS

The total macular volume is an interpolated number from OCT that indicates retinal thickness averaged over the macular region, and gives an estimate of macular retinal volume. For most patients, macular volume was below the Stratus normal range of 6.2–7.4 mm3 (Table 1). For both CNTF3 and CNTF4 studies there was a significant increase in total macular volume in the study eye compared with baseline in the high-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor groups (P < .001) but not in the sham groups (Table 3). In the low-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor groups, there was a statistically significant difference in the change in total macular volume in the study eye compared with baseline in the CNTF4 study (P = .001) but not in the CNTF3 study (P = .148) (Table 3).

To determine whether the observed increase in macular volume was attributable to pathologic changes of the retina, the frequency and incidence of cystic macular edema, epiretinal membrane, vitreomacular traction, and choroidal neovascularization at baseline and 12 months were evaluated for each treatment group by masked graders. There was no increase in incidence or frequency of any pathologic changes associated with the high- and low-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor groups compared with the sham group (Table 5). In addition, when eyes with any of the above pathologies were excluded, the remaining high- and low-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor groups still had a significant increase in total macular volume compared with the baseline.

TABLE 5.

Pathologic Changes From Baseline at 12 Months in Patients Receiving Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Retinitis Pigmentosa

| Endpoint | CNTF3

|

CNTF4

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Dose Implant/Sham | High-Dose Implant/Sham | Low-Dose Implant/Sham | High-Dose Implant/Sham | |

| Change in macular edema total | 18/18 | 36/36 | 19/19 | 47/47 |

| No | 15 (83%)/15 (83%) | 25 (69%)/26 (72%) | 10 (53%)/9 (47%) | 17 (36%)/16 (34%) |

| Yes | 3 (17%)/3 (17%) | 11 (31%)/10 (28%) | 9 (47%)/10 (53%) | 30 (64%)/31 (66%) |

| Change in epiretinal membrane total | 18/19 | 41/39 | 19/19 | 47/46 |

| No | 7 (39%)/5 (26%) | 6 (15%)/10 (26%) | 11 (58%)/10 (53%) | 21 (45%)/23 (50%) |

| Yes | 11 (61%)/14 (74%) | 35 (85%)/29 (74%) | 8 (42%)/9 (47%) | 26 (55%)/23 (50%) |

| Change in vitreomacular attachment total | 17/18 | 36/37 | 19/19 | 47/45 |

| No | 15 (88%)/18 (100%) | 32 (89%)/33 (89%) | 18 (95%)/16 (84%) | 45 (96%)/42 (93%) |

| Yes | 2 (12%)/0 (0%) | 4 (11%)/4 (11%) | 1 (5%)/3 (16%) | 2 (4%)/3 (7%) |

CNTF3 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for late-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 3; CNTF4 = ciliary neurotrophic factor for early-stage retinitis pigmentosa study 4.

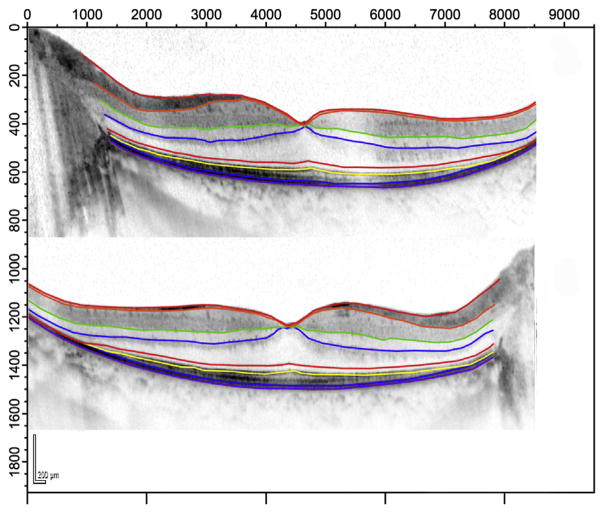

To determine whether the observed increase in macular volume was attributable to increased thickness of individual retinal layers, spectral-domain (SD) OCT scans (Heidelberg Spectralis HFA + OCT) were obtained from 10 patients in the high-dose CNTF4 group. Since SDOCT was not available at baseline, ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated eyes were compared with sham-treated eyes at the 12-month-visit by masked observers. Representative examples of segmented scans are shown in Figure 2. For this patient, the outer nuclear layer shows a higher average thickness in the left (high-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor) eye (Figure 2, Top) than in the sham-treated eye (Figure 2, Bottom) (79.4 μm vs 72.8 μm). Since some eyes had CME in the fovea, measures of segment thickness were obtained from locations 1.7 μm (6 degrees) nasal and temporal to the fovea. Consistent with findings in the larger group, the total retinal thickness in this subgroup was greater in ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated eyes than in sham-treated eyes (301 μm vs 270 μm; t = 4.24; P = .002). Average outer nuclear layer thickness was significantly higher in the ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated eyes (57 μm vs 45 μm; t = 3.18; P = .01). However, the segments reflecting photoreceptor outer segment and retinal pigment epithelium thickness were comparable in ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated vs sham-treated eyes (32 μm vs 35 μm; t = −1.1; P = .3).

FIGURE 2.

Representative Spectralis spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scans (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) from the horizontal midline of a 30-year-old patient with retinitis pigmentosa at 12 months post implant. (Top) Ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated left eye. (Bottom) Sham-treated right eye. Colored lines are borders obtained with Igor segmentation program. Light green: Bruch membrane/choroid border; yellow: ellipsoid zone (inner/outer segment border); blue: inner nuclear layer/outer plexiform layer border.

ENCAPSULATED CELL IMPLANTS AFTER REMOVAL

For CNTF3 (12 months post implant) on postexplant testing, the lower-dose capsules produced ciliary neurotrophic factor at 0.17 ± 0.06 ng/day (n = 3), and higher-dose capsules produced ciliary neurotrophic factor at 2.02 ± 0.61 ng/day (n = 9). For CNTF4 (24 months post implant), on postexplant testing, the lower-dose capsules produced ciliary neurotrophic factor at 0.15 ± 0.17 ng/day (n = 5), and higher-dose capsules produced ciliary neurotrophic factor at 1.08 ± 0.5 ng/day (n = 10).

DISCUSSION

CNTF3 AND CNTF4 STUDIES WERE PROSPECTIVE, MASKED, randomized studies to evaluate the safety profile of the encapsulated cell–ciliary neurotrophic factor implant, to determine the effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal structure and visual function, and to explore the dose and primary endpoint for future studies in patients with RP. Neither study demonstrated a significant improvement in their respective endpoints: BCVA at 12 months for CNTF3 and visual field sensitivity at 12 months for CNTF4.

The surgical procedure was well tolerated. There were no serious adverse events related to the implantation procedure or the active study agent. No ciliary neurotrophic factor was detectable in the serum and no serum antibodies against ciliary neurotrophic factor or encapsulated cells could be detected, suggesting there was no systemic exposure. All explanted devices contained viable cells and delivered expected amounts of ciliary neurotrophic factor. The most frequent adverse event was miosis, observed in 25.6% for CNTF3 and 31.3% for CNTF4 patients receiving the high-dose implants, presumably attributable to the parasympathetic effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor on the circular muscle fibers of the iris.15 It is important to note that miosis was not associated with high-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated patients with geographic atrophy,16 indicating it is an observation unique to the RP patients, many of whom have enlarged pupils in standard lighting.17

These trials did not demonstrate a therapeutic benefit of ciliary neurotrophic factor in either of the primary outcome measures at 12 months. In CNTF3, BCVA appeared stable for the majority of patients in all treatment groups, including sham-treated eyes, for the 12-month study period. In CNTF4, the decrease in visual field sensitivity from baseline to 12 months in the high-dose arm was significantly greater than in the sham eyes. Given that the change in overall sensitivity was based on 76 points, the average decrease for high-dose ciliary neurotrophic factor eyes was 1.29 dB per locus for CNTF3 and 2.16 dB per locus for CNTF4. Although the observed visual field sensitivity changes are small, the cumulative effect from high-dose implants placed in eyes for many years could be become consequential and, thus, long-term use of the high-dose implant does not appear warranted for retinitis pigmentosa. At 6 months post explant, visual field sensitivity was not significantly different between the ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated and sham-treated groups and the ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated eyes showed comparable total sensitivity loss to the control eyes (Figure 1), suggesting that the decrease is transient or reversible. In animal models, ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated photoreceptors show reduced visual sensitivity, but ultimately survive longer with improved visual function compared with the contralateral sham-treated eyes.18 The present data are consistent with a similar mechanism for cone phototransduction regulation and survival in humans (Figure 1) but, because of the slow progression of retinal degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa,19–22 a convincing demonstration of long-term benefit will require longer follow-up.

Ciliary neurotrophic factor demonstrated a significant biological effect in increased total macular volume in treated eyes (Table 3). Although average macular volume was still lower than in normal eyes, the relative change in macular volume from baseline was highly statistically significant in the high dose–treated group. The increased total macular volume may be related to an increased retinal cell number, increased cell volume, increased volume of Henle fiber layer, retinal toxicity, or a combination of these factors. There was no evidence of a toxic effect, as shown by lack of difference in cystoid macular edema or epiretinal membrane in ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated eyes compared with sham-treated eyes, and by the lack of any visual acuity loss at 12 months.23 A subset of eyes from 1 center in the CNTF4 trial was studied using SDOCT to segment individual retinal layers. The measured increase in outer nuclear layer thickness predicted a 0.34 mm3 increase in macular volume, consistent with the increase found in the full cohort. The photoreceptor outer segment layer was not different between high-dose-implanted and sham-treated eyes. The scans acquired did not permit quantitative analysis of the thickness of Henle fiber layer or outer plexiform layer, so the increase in the “outer layer complex”24 may reflect changes in the outer nuclear layer and/or changes in Henle fiber layer and outer plexiform layer. The increased width of the outer layer complex appears to parallel changes observed in preclinical studies11,25 and outer nuclear layer protection by ciliary neurotrophic factor in the rat, dog, and rabbit models.25,26 Cone preservation has been shown with Adaptive Optics Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy in ciliary neurotrophic factor–treated eyes compared with the sham-treated fellow eyes in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome type 2.27 However, the relative preservation of cones was not accompanied by any detectable changes in visual function measured by conventional means, including visual acuity, visual field sensitivity, and ERG, indicating that these conventional outcome measures may not have adequate sensitivity in a short-duration trial.

Biography

Dr David G. Birch, PhD, takes a multidisciplinary approach to retinal degenerative diseases, utilizing electrophysiology, psychophysics and retinal imaging. He has served as principal investigator on several single site and multi-center clinical trials in retinal degenerative diseases, received an Achievement Award from the American Academy of Ophthalmology, is a Fellow of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology and is the author of over 250 scientific papers.

Dr David G. Birch, PhD, takes a multidisciplinary approach to retinal degenerative diseases, utilizing electrophysiology, psychophysics and retinal imaging. He has served as principal investigator on several single site and multi-center clinical trials in retinal degenerative diseases, received an Achievement Award from the American Academy of Ophthalmology, is a Fellow of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology and is the author of over 250 scientific papers.

CNTF3 and CNTF4 RP Study Groups

David G. Birch, Retina Foundation of the Southwest; Richard G. Weleber, Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University; Jacque L. Duncan, University of California, San Francisco; Jill J. Hopkins, Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group, Los Angeles; David G. Telander, University of California, Davis; Ronald E. Carr, New York University Medical Center; John R. Heckenlively, Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan; Timothy W. Olsen, Emory University; Alex Iannaccone, The Hamilton Eye Institute, University of Tennessee; Lawrence S. Halperin, Retina Group of Florida, Ft. Lauderdale; Kang Zhang, Shiley Eye Center and Institute for Genomic Medicine, University of California San Diego; Sandeep Grover, University of Florida; Byron L. Lam, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami.

Trial registration (ClinicalTrials.gov): CNTF3: NCT00447993 A Study of Encapsulated Cell Technology (ECT) Implant for Patients With Late-Stage Retinitis Pigmentosa; CNTF4: NCT00447980 A Study of Encapsulated Cell Technology (ECT) Implant for Patients With Early-Stage Retinitis Pigmentosa.

The IRBs responsible for these studies are as follows: Baylor Research Institute Institutional Review Board, Dallas, Texas; Western Institutional Review Board, Olympia, Washington; Kosal Bo Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Staff Management Office, Los Angeles, California; University of Utah Institutional Review Board, Salt Lake City, Utah; William Beaumont Hospital Research Institute Human Investigation Committee, Royal Oak, Michigan; OHSU Institutional Review Board, Portland, Oregon; Committee on Human Research Institutional Review Board, University of California, San Francisco, California; Research Subjects Protection Program, Minneapolis, Minnesota; University of California, Davis, IRB, Sacramento, California; NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, New York, New York; University of Michigan IRB MED Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Methodist Hospital Research Institute IRB, Memphis Tennessee; University of Miami Human Subjects Research Office, Miami, Florida.

The authors are indebted to the members of the data safety monitoring committee: Donald J. D’Amico, Weill Cornell Medical College (chair); Thomas R. Friberg, University of Pittsburgh; Alan M. Laties, University of Pennsylvania; Raymond Iezzi, Mayo Clinic; and David C. Musch, University of Michigan; to the members of Duke University OCT Reading Center; to the members of Neurotech clinical research team for their invaluable assistance in the conduct of this study; and to Paul Sieving, National Eye Institute, for his original inception of the study and protocol design. Drs Donald C. Hood (Columbia University) and Yuquan Wen (Retina Foundation of the Southwest) provided software for OCT segmentation.

Footnotes

ALL AUTHORS HAVE COMPLETED AND SUBMITTED THE ICMJE FORM FOR DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST. David Birch and Glenn Jaffe received consulting fees from Neurotech USA, Inc., Lincoln, Rhode Island; Weng Tao is an employee of Neurotech USA, Inc., Lincoln, Rhode Island. Neurotech USA, Inc., Lincoln, Rhode Island, provided financial support for these studies. Contributions of authors: design of the study (D.G.B., W.T., R.G.W.); data analysis (D.G.B., W.T., G.J.J.); manuscript preparation (D.G.B., W.T., J.L.D.); all authors were involved with the conduct of the studies and had full access to the data, contributed to the data interpretation, and provided revisions to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sieving PA. Retinitis pigmentosa and related disorders. In: Yanoff MDJ, editor. Ophthalmology. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2003. pp. 1652–1653. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hims MM, Daiger SP, Inglehearn CF. Retinitis pigmentosa: genes, proteins and prospects. Dev Ophthalmol. 2003;37:109–125. doi: 10.1159/000072042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faktorovich EG, Steinberg RH, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, LaVail MM. Photoreceptor degeneration in inherited retnal dystrophy delayed by basic fibroblast growth factor. Nature. 1990;347(6288):83–86. doi: 10.1038/347083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaVail MM, Unoki K, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Yancopoulos GD, Steinberg RH. Multiple growth factors, cytokines and neurotrophins rescue photoreceptors from the damaging effects of constant light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(23):11249–11253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaVail MM, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, et al. Protection of mouse photoreceptors by survival factors in retinal degenerations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(3):592–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald NQ, Chao MV. Structural determinants of neurotrophin action. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(34):19669–19672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuhrmann S, Kirsch M, Hofmann HD. Ciliary neurotrophic factor promotes chick photoreceptor development in vitro. Development. 1995;121(8):2695–2706. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuhrmann S, Grabosch K, Kirsch J, Hofmann HD. Distribution of CNTF receptor alpha protein in the central nervous system of the chick embryo. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461(1):111–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.10701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cayouette M, Gravel C. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor can prevent photoreceptor degeneration in the retinal degeneration (rd) mouse. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8(4):423–430. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.4-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cayouette M, Behn D, Sendtner M, Lachapelle P, Gravel C. Intraocular gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor prevents death and increases responsiveness of rod photoreceptors in the retinal degeneration slow mouse. J Neurosci. 1998;18(22):9282–9293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09282.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tao W, Wen R, Goddard MB, et al. Encapsulated cell-based delivery of CNTF reduces photoreceptor degeneration in animal models of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(10):3292–3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sieving PA, Caruso RC, Tao W, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) for human retinal degeneration: phase I trial of CNTF delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(10):3896–3901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck RW, Moke PS, Turpin AH, et al. A computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(2):194–205. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01825-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood DC, Lin CE, Lazow MA, Locke KG, Zhang X, Birch DG. Thickness of receptor and post-receptor retinal layers in patients with retinitis pigmentosa measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(5):2328–2336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbin G, Manthorpe M, Varon S. Purification of the chick eye ciliary neurotrophic factor. J Neurochem. 1984;43(5):1468–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang K, Hopkins JJ, Heier JS, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants for treatment of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(15):6241–6245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018987108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birch EE, Birch DG. Pupillometric measures of retinal sensitivity in infants and adults with retinitis pigmentosa. Vision Res. 1987;27(4):499–505. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Tao W, Luo L, et al. CNTF induces regeneration of cone outer segments in a rat model of retinal degeneration. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fishman GA, Bozbeyoglu S, Massof RW, Kimberling WJ. Natural course of visual field loss in patients with Type 2 Usher syndrome. Retina. 2007;27(5):601–608. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000246675.88911.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, Alexander KR, Derlacki DJ. Rate of visual field loss in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(3):460–465. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iannaccone A, Kritchevsky SB, Ciccarelli ML, et al. Kinetics of visual field loss in Usher syndrome Type II. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(3):784–792. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birch DG, Anderson JL, Fish GE. Yearly rates of rod and cone functional loss in retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(2):258–268. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDonald IM, Sauve Y, Sieving PA. Preventing blindness in retinal disease: ciliary neurtrophic factor intraocular implants. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(3):399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhee KD, Ruiz A, Duncan JL, et al. Molecular and cellular alterations induced by sustained expression of ciliary neurotrophic factor in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1389–1400. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush RA. Encapsulated cell-based intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor in normal rabbit: dose-dependent effects on ERG and retinal histology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(7):2420–2430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeiss CJ, Allore HG, Towle V, Tao W. CNTF induces dose-dependent alterations in retinal morphology in normal and rcd-1 canine retina. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82(3):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talcott KE, Ratnam K, Sundquist SM, et al. Longitudinal study of cone photoreceptors during retinal degeneration and in response to ciliary neurotrophic factor treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(5):2219–2226. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]