Abstract

Despite increasing prevalence of bariatric surgery, little is known about why patients seek out this treatment option. Heads Up is an observational study sponsored by a large benefits management group that examines surgical and nonsurgical approaches to weight management in obese adults. This study examined patients' reasons for choosing surgery. The sample included 360 adult obese patients seeking bariatric surgery who were invited to volunteer for a surgical or a medical weight loss program by their insurer. Participants rank ordered their top three reasons as a deciding factor for choosing to consider surgery. The top three reasons were concerns regarding health (52 %), current obesity-related medical conditions (28 %), and improved physical fitness (5 %). Overall, 13 % endorsed insurance coverage as one of their top three choices. When insurance coverage is assured, health and functionality issues were the major reasons reported for obese adults choosing to undergo bariatric surgery.

Keywords: Weight loss, Morbidobesity, Patientmotivation, Bariatric surgery, Surgical decision

With more than one third of US adults suffering from obesity and with no clear decreases in obesity rates [1], obesity is of great public health concern [2]. Surgical weight loss techniques have gained in popularity. For example, in 2008, 344,221 gastric bypass surgeries were performed worldwide, of which 220,000 were performed in the USA alone [3]. There is growing appreciation of the health benefits of weight loss achieved by bariatric surgery procedures, including a reduction in mortality and CVD events [4, 5] and demonstration of reversal of type 2 diabetes [6, 7]. Still, the number of surgical cases in the USA represents only a small fraction of those who meet guideline criteria [8]. This study seeks to examine why patients who are offered the option for bariatric surgery choose to do so.

Background

Although evidence indicates that surgical interventions are successful in reducing weight among obese individuals [9], it is not clear what individuals' motivations are for electing medical interventions rather than surgical interventions or vice versa. To the authors' knowledge, only four studies have examined motivations for individuals' desire to undergo weight loss surgery, and those studies have predominately focused on appearance or health reasons and have not specifically addressed whether reimbursements by insurance companies may play a role [10–13].

In the first study, Libeton and colleagues [10] assessed individuals' motivations for obtaining the adjustable gastric band procedure. The participants were asked to rank a total of six statements (fitness, limitations, health, medical, appearance, embarrassment), in order from the most reflective reason to the least reflective reason for undergoing the surgery. Results revealed that the number one reason was health concerns (n=59; 28.4 %) followed by appearance (n=49; 23.6 %) and medical condition (n=49; 23.6 %). Gender differences were also present; women were more likely to select appearance as their top reason, whereas men were more likely to select medical condition. In another study, Wee and colleagues [13] were interested in examining both individuals' expectations and motivations for pursuing bariatric surgery in a total of 44 adults. Patients were asked what they wished to attain as a result of surgery. Results from this study found that health reasons were the most important factor in pursuing bariatric surgery (84 %).

In 2007, Munoz and colleagues [11] employed a mixed-model design to explore reasons for 109 individuals seeking bariatric surgery. The authors utilized an open-ended question that stated: Why are you seeking weight loss surgery? The order in which the participants wrote their responses were categorized by the authors as the individuals' first, second, and third reason for their desire to have bariatric surgery, and those reasons were then placed into categories to calculate percentages. The primary reason for surgery was for health (73 %), followed by preventive purposes (16 %).

In another study [12], obese African–American women's perceptions of bariatric surgery and barriers to weight loss were explored. These women were not actively seeking bar-iatric surgery at the time of this study. A total of 41 women participated in 90-min semi-structured focus groups. The question pertinent to reasons for undergoing bariatric surgery was: What would influence you to consider weight loss surgery for yourself? [12]. Themes from the focus group concerning bariatric surgery focused predominately on the potential for complications from the surgery. The only mention of insurance coverage was in the context of insurance companies' lack of coverage for nonsurgical weight management methods.

From these previous studies, it is evident that health reasons were the number one reason for patients electing to pursue bariatric surgery. However, two of these four previous studies did not provide the option to select insurance coverage as a reason; only two studies allowed for the possibility of insurance coverage to arise as a reason due to the studies' designs (i.e., open-ended [11], semi-structured focus group [12]). It is possible that the initial cost of surgical interventions may be a potential barrier that may outweigh an individual's perception of how deleterious obesity is to their health; however, as noted above, previous studies have not examined the extent to which this may influence individuals' desire for bariatric surgery.

As such, the current study examined patients' top three reasons for electing to undergo weight loss surgery, including reasons examined in previous studies, but also with the option to select insurance coverage, to specifically elucidate whether insurance coverage was a deciding factor. Based on previous research, it was hypothesized that health would emerge as a predominant reason for pursuing surgical weight loss. However, due to the dearth of information available, no specific hypothesis was generated regarding whether insurance coverage is related to the pursuance of weight loss surgery.

Methods

Sample

This study utilized data from an observational study (Heads Up) that was sponsored by a benefits management group. All covered members were invited to volunteer for an intensive medical program or surgical treatment for weight loss if they had a BMI≥35 kg/m2 with type 2 diabetes or a BMI≥40 kg/m2. Potential volunteers were directed to a website with information on obesity, medical weight loss, surgical weight loss, and details of the program. Individuals could volunteer for one or both of the options. Volunteers were selected randomly by district (six districts across the state) to be screened for eligibility for the surgical or medical programs. Those who chose bariatric surgery received one of three surgeries: adjustable gastric band, sleeve gastrectomy, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass after screening and approval by a panel of expert clinicians. Only those who volunteered and were approved for the bariatric surgery option were included in the current study.

Instrumentation

Patient Motivation for Bariatric Surgery Questionnaire

The Patient Motivation for Bariatric Surgery Questionnaire was adapted from the Munoz et al. [11] study questionnaire to assess participants' motivations for seeking weight loss surgery. The current questionnaire includes eight statements reflecting reasons for seeking weight loss surgery, including (1) appearance, (2) medical conditions, (3) physical fitness, (4) health concerns, (5) employment, (6) physical limitations, (7) encouragement from others, and (8) insurance coverage. Participants were asked to rank order the statements from the (1) most important to the (8) least important reason for electing bariatric surgery.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 21.0. First, descriptive data were calculated to characterize the participant population. Next, frequencies and percentages, means, and standard deviations (where appropriate), were examined to determine participants' reasons for undergoing bariatric surgery. Finally, a series of chi-square tests were performed to assess any potential differences in race, gender, presence of diabetes, and obesity classification. Results at p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 360 adult obese individuals were included in the current study. The majority of participants were Caucasian (62 %) and female (87 %). The mean age was 46.1 years (SD=10.22) and mean BMI was 47.4 kg/m2 (SD=5.47). Please see Table 1 for additional demographic characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of bariatric surgery patients (N=360).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 46.05 (10.22) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 47 (13.1) |

| Women | 313 (86.9) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 222 (61.7) |

| African–American | 120 (33.3) |

| Other | 18 (5.1) |

| Diabetes (% yes) | 120 (33.3) |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 47.44 (5.47) |

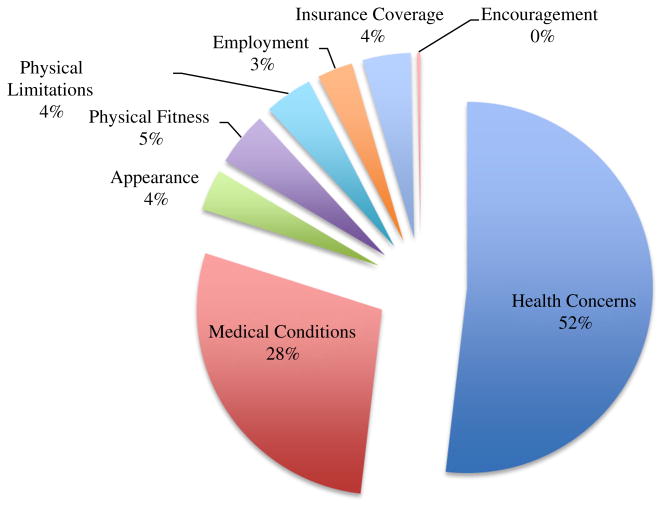

Of the 360 participants, 187 (52 %) rated health concerns (I am concerned that my health will deteriorate and my life may be shortened) as their number one reason for undergoing bariatric surgery. Medical conditions (I want to improve medical conditions associated with my obesity) were the second most commonly reported primary reason and functionality the third (fitness 5 % and physical limitations 4 %). Only 4 % selected appearance as the primary reason. Of particular interest to the current study, only 15 (4 %) individuals selected insurance coverage (i.e., the surgery paid for by their insurance company) as their first choice reasons for seeking weight loss surgery. Please see Fig. 1 for additional details. Men and women did not significantly differ in their number one reason, χ2 (7, N=360)=6.11, p=0.53, nor did Caucasian and African–Americans, χ2 (7, N=342)=13.57, p=0.06. There was, however, a significant difference between diabetics and nondiabetics, χ2 (7, N=360)=26.90, p<0.001. Specifically, compared to diabetics, nondiabetics were less likely to rate medical condition and more likely to rate health concerns as their number one reason.

Fig. 1. Primary reason that patients sought weight loss surgery (N=360).

When expanded to examine individuals' top three reasons for undergoing bariatric surgery, health concerns (52 %), medical conditions (35 %), and physical fitness (32 %) were selected. Appearance was endorsed by 74 (21 %) participants as one of their top three choices. Only 46 (13 %) participants endorsed insurance coverage as one of their top three choices.

Conclusion

Our overall conclusion is that patients who have access to bariatric surgery according to guideline eligibility are primarily motivated by health concerns, medical issues, and functionality issues. Appearance does not appear to be a strong motivator. This is consistent with previous studies [10, 11, 13], where health concerns were the top reason participants selected for undergoing bariatric surgery. However, gender differences were not present in the current sample.

As with all studies, this study is not without limitations. First, data were collected on participants from one state; however, the sample was racially diverse. Thus, because of this diversity and the insignificant racial differences, results may be generalizable to individuals of various races. Second, all participants were offered the surgical option for weight reduction as a component of their insurance program. A limitation of the study is that all patients would have their surgery covered by their insurer, raising the issue that insurance coverage would not be an issue in motivation for surgery. Because they were prompted through the insurance program offering this benefit, future studies may wish to examine reasons for pursuing bariatric surgery among a more general population of bariatric patients.

From the results, it appears that insurance reimbursement was not a driving factor for the majority of obese individuals electing bariatric surgery in this sample, although some individuals did select this as their top reason. Perhaps those individuals had been considering bariatric surgery prior to being offered the option for reimbursement for the procedure. However, the main factors for selecting bariatric surgery were health reasons. Nonetheless, these findings should be examined in context; the included participants had established obesity, yet elected for bariatric surgery when it was a benefit of their health insurance program.

With the American Medical Association [14] now joining The Obesity Society in recognizing obesity as a disease [15], it is possible that there will be an increased demand for insurance coverage of surgical and nonsurgical weight loss techniques. If this is the case, alteration of the reasons for seeking bariatric surgery questionnaire will be necessary, perhaps including the question of whether an individual had previously sought bariatric surgery but did not follow through may provide insurance coverage-specific information. It is possible that results from a revised survey would better elucidate whether an individual chose to undergo bariatric surgery only after insurance coverage is offered. The authors recommend close attention to these issues as there is still a large majority of patients who do not seek bariatric surgery when guidelines [8] would indicate that they could potentially achieve health benefits.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All the authors have no potential conflicts of interest and no disclosures to report.

Contributor Information

Phillip J. Brantley, Email: phil.brantley@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Krystal Waldo, Email: krystal.kleabir@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Molly R. Matthews-Ewald, Email: Molly.Matthews-Ewald@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Ricky Brock, Email: Ricky.Brock@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Catherine M. Champagne, Email: Catherine.Champagne@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Tim Church, Email: Timothy.Church@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Melissa N. Harris, Email: Melissa.Harris@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Tipton McKnight, Email: tipmcknight@yahoo.com, Office ofGroup Benefits, State of Louisiana, Baton Rouge, LA, USA.

Melanie McKnight, Email: Melanie.mcknight@brgeneral.org, Baton Rouge General Internal Medicine Residency Program, Baton Rouge, LA, USA.

Valerie H. Myers, Email: VMyers@kleinbuendel.com, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

Donna H. Ryan, Email: Donna.Ryan@pbrc.edu, Behavioral Medicine Laboratory, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visscher TLS, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:355–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide. Obes Surg. 2013;19:1605–11. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, et al. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:383–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaede P, Lund-Anderson H, Parving HH, et al. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:580–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1577–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1567–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6(Supp2):51S–209. PUBID: 9813653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(41) doi: 10.3310/hta13410. PUBID: 19726018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libeton M, Dixon JB, Laurie C, et al. Patient motivation for bariatric surgery: characteristics and impact on outcomes. Obes Surg. 2004;14:392–8. doi: 10.1381/096089204322917936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz DJ, Lal M, Chen EY, et al. Why patients seek bariatric surgery: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of patient motivation. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1487–91. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch CS, Chang JC, Ford AF, et al. Obese African-American women's perspectives on weight loss and bariatric surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:908–14. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0218-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wee CC, Jones DB, Davis RB, et al. Understanding patients' value of weight loss and expectations for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:496–500. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollack A. A.M.A. recognizes obesity as a disease. The New York Times; http://www.nytimes.com. [Google Scholar]

- 15.TOS Obesity as a Disease Writing Group. Obesity as a disease: a white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the Council of the Obesity Society. Obesity. 2008;16:1161–77. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]